Point of view is worth 80 IQ points.

—Alan Kay

Some people ask us if we build object models because we program in object-oriented languages. That’s not why. We don’t object model to write object-oriented code, we write object-oriented code because we object model. We’re used to thinking that way.1 Other ways of thinking about and writing code look very unattractive once you grasp the object-oriented way of thinking and its benefits. Success in object modeling requires two abilities: (1) good object think, and (2) good object selection. This chapter briefly discusses object think and introduces categories for consistently and accurately selecting objects. It is important to recognize that the information gathered through object modeling is not the only set of requirements gathered. Some requirements are more subjective and have to do with user experience and user interactions. Other requirements are more technical and specify the operating environment of the system. These are captured by methods other than object modeling, but are driven by the domain defined in the object model.

Object think is key to properly encapsulating data and functionality within objects. Poor object thinkers put data and functions into objects haphazardly. At best, they use a set of guidelines they find difficult to explain. This makes their models and code difficult to understand and brittle to changes in requirements and system growth. When requirements change, a brittle object model must significantly alter its structure by redefining objects, rearranging collaborations, and shuffling responsibilities between objects. Object models built through functional analysis are filled with objects representing functions, which makes them notoriously brittle as changes in functional requirements render objects obsolete, and reorder collaborations among them.

Good object thinkers apply consistent principles for distributing data and functions; they can explain and justify the results in their object models by relating them back to the objects in the business domain. Object models built with object think remain stable as the requirements and the system evolve because the model mirrors real-world objects and their relationships. New requirements mean more of the domain is being modeled or more responsibilities are being given to the objects that are already modeled. These changes are neatly encapsulated in a stable object model by adding new objects and expanding objects’ responsibilities. Objects do not change their meaning or lose collaborators, so the underlying structure of the model remains intact even as new layers are snapped on top of it.

Rule one of object think is to personify objects and conceive of them as active, knowledgeable entities.2 From the object personification point of view, a domain of entities and processes becomes a collection of active objects capable of undertaking complex actions in response to outside requests. A model produced by object personification has an organization that reflects the natural structure of the domain. The opposite of object personification is the functional perspective that models a domain as a collection of functions working on data.

Rule two of object think is to adopt the “first-person” voice when discussing objects. Under the first-person perspective, all statements about an object are expressed using the pronoun “I.” Speaking of objects in the first-person voice is useful for determining precisely what responsibilities an object needs, along the lines of “If I am this object, do I really need to know about X, or really need to be able to do Y?”

Rule three of object think is to transform knowledge about an object and the functions performed on it into responsibilities of the object. Under the responsible objects perspective, functions performed on an object become services the object performs; data recorded about an object become properties the object maintains; and links to other things become collaborations with other objects, formed according to business rules.

EXAMPLE—A fruit juice bottling plant keeps statistics on all of its bottling lines that include the theoretical cases per hour it can produce under 24/7 operation, and the actual number of cases it produces in a month. These statistics are used to calculate each bottling line’s monthly efficiency.

Applying object think:

I’m a fruit juice bottling line. I know my theoretical cases-per-hour limit and how many cases I produce in a given month. I know how to calculate my theoretical limit for each month, and I know how to calculate my case efficiency for each month.

Finding objects is easy if you know how and where to look for them. How to look is simple; use object think to ask questions of domain experts. Where to look is straightforward, too; look for objects in the following four categories: people, places, things, and events.

Listening to domain experts and probing for people, places, things, and events are simple, yet powerful activities in the object modeling methodology. They direct attention away from users, screens, and technologies and toward understanding the underlying business domain. We learned this methodology from Peter Coad, the author of one of the very first books on object-oriented analysis.3 While working with Peter, object modeling complex domains all over the world, one of us co-authored a book4 with him on object modeling and patterns. In this book were 31 object modeling patterns. Over the past several years, we have, through practical application on commercial systems, whittled and transformed these patterns down to 12 pairs of players.5 As expected, each object in these 12 pairs belongs to one of the four domain categories. When you know the objects in the domain categories and are able to recognize them in the responses of domain experts, then you will be well on your way toward becoming a very effective object modeler. The remainder of this chapter introduces the domain objects, and the next chapter shows how these objects form the 12 object patterns we use for modeling.

People play a big part in nearly all domains. Information to capture about people includes details identifying individuals, the different contexts in which they can participate, their privileges and duties in those contexts, and records of their interactions. Often people participate not on their own behalf, but on behalf of a company or agency; however, object think dictates that it is the organization that is bidding, buying, and selling, and otherwise acting like a single individual. To model a person or an organization that can participate in the system, use an actor object. Model the participation and actions of the person or organization with separate objects.

A simple rule of object modeling is that every action by a person or an organization happens within a context. A context is a focused piece of the business domain that concentrates on the information and rules necessary to reach a single goal. Putting an action within a context helps ensure the action is only undertaken by those able to participate in that context, and that the action only involves other people, places, and things within that context.

EXAMPLE—In an e-commerce system for ordering office supplies, a person can participate as an individual customer, as a buyer for a business, as a supplier agent, and as a system administrator. The same person may be able to participate in more than one of these roles. Fred is both a customer and a business buyer. When Fred logs in as a business buyer, he enters a different context than when he logs in as an individual customer. Prices and discounts may differ, and he can use a purchase order to acquire supplies, something he cannot do as an individual customer. Peggy Sue, acting as a supplier agent, can update inventory for her company’s products on the site. Billy Bob, acting as a system administrator, can update pricing and discounts.

Whenever a person or organization participates in a context, two things inevitably happen. First, the system endows the person or organization with permissions, IDs, and passwords necessary to distinguish and track that person or organization within that context. Second, the person or organization’s participation acquires its own history, recording the events undertaken within that context. Objectify the obvious. For each context a person or organization participates in, create a role object that has the permissions, IDs, and passwords necessary to participate in the context, and that has associated to it the records of interactions within the context.

EXAMPLE—In the above e-commerce system, create separate role objects for each goal-based action: customer orders products; business buyer orders products for organization; supplier agent sells products; and system administrator creates and manages the accounts and other information in the system. Fred has two role objects: a customer role for his personal orders, and a business buyer role for his company orders. His personal billing and shipping information is held with his customer role, along with his personal orders. His company billing and shipping information, along with his company orders, are held with his business buyer

role. Both roles are associated to the person object representing Fred; this common object allows Fred to get to both roles through a single login.

We often say a person like Fred is “taking on many roles.” Organizations take on roles, too, possibly many. In general, use a role object to model how a person appears and what a person does in a given context. Ditto for organizations. They’re people, too.

Another simple rule of object modeling is that every recorded action by a person or organization happens in a given place.6 In a simple system where all actions occur at the same location, having an explicit place object maybe be redundant; however, adding it now simplifies expansion to a system with multiple locations later.

EXAMPLE—A retail clothing store seeks to consolidate all its orders in one database, but wants to be able to distinguish those that were purchased online from those that occurred in a physical store or were catalog telephone orders. In the model, an order can occur in one of three places: physical store, online store, or telephone catalog store.

Places are often hierarchical for the following reasons: (1) a position for a localized place cannot be fully specified without putting it inside a larger place,7 and (2) recorded actions in localized places are rolled up into larger places for auditing or statistical comparison. The smallest place of interest is where recorded actions occur. A location that merely contains things, but is not a location for recorded actions, is not a place, but a container (see Section 2.2.6). To model a location where recorded actions occur, use a place object; to model a location that contains places, use an outer place object.

EXAMPLE—In the retail clothing store example, each physical store is assigned to a geographical region overseen by a regional supervisor. The performance of each geographical region is determined by rolling up the orders placed at the physical stores within it.

In the retail clothing store example, there are only two levels, and the geographical region is acting as an outer place; however, if the nesting of levels was greater, then the geographical region might itself be a place contained within an outer place.

A place, just like a person or organization, can take on different roles depending on the context in which the place is viewed. To model the appearance and participation of places in different contexts, use role objects.

EXAMPLE—An airport can be either or both a civilian airport and a military airport. An airport gate can be possibly one or more of the following gate roles: international, interstate, or intra-state.

Every real-world action involves a subject that is the entity being acted upon. A tangible entity that can be the subject of an action is considered a thing. When people and places are the subjects of actions, they are acting like things.8

To describe a real-world thing requires two objects. The first object provides a general, high-level description of the thing that is abstract enough to be shared with other similar things. In effect, this general description defines a set of related things. The second object is a specific description that extends the general description and distinguishes the thing from others in the set.

Decomposing a thing into general and specific descriptions resembles a data modeling technique called normalization; but this is not normalization, because the goal of normalization is to avoid replicating data. Objects are more than just data; they have behaviors, too. Having one general description for many specific descriptions allows data sharing, but it also allows for behaviors within the general description that work across all the specific objects, for instance, rank them from best to worst.

To model the general description of a set of things, use an item object, which is a reusable description for many particular things. Use a specific item to model the properties that distinguish a particular thing from other things with the same item description.

EXAMPLE—An automobile belongs to a set that is defined as all cars with a certain manufacturer, make, model, and production year, but it also has unique characteristics, such as its color, options, and vehicle identification number. Model the automobile with two objects: an automobile description containing the general characteristics, and an automobile object containing its unique characteristics. The automobile description object is reusable for all similar automobiles.

Use role objects for things that can participate in multiple contexts or have multiple uses.

EXAMPLE—A master videotape is stored within a storage library and has a storage role that participates in the checking-in and checking-out events. The same videotape is also converted to a digital file so that segments can be extracted into online videos. The videotape has a digital master role that participates with the editing events to track the history of the videotape’s usage in online videos and the number of minutes involved.

As with places, a thing can be tracked at different hierarchical levels of scale. Going up the scale, a thing can be placed within a container, classified within one or more groups, or fitted as a part into an assembly; going down the scale, a thing can act as a container, a group, or an assembly. It is quite common for a thing to exist at both levels; for example, a part in an assembly may itself be assembled out of smaller parts.

To model a thing that is a receptacle or storage place for other things, use a container object. Use a content object to represent a thing that is placed in a container. A content object can only be in at most one container at a given time, although its container may be a content object in another container.

EXAMPLE—A television network sends its master videotapes to a videotape storage library. Each videotape is bar-coded and assigned a storage location. When the network recalls the videotape, and later returns it to the library, the videotape is again assigned a storage location that may or may not be the same as its previous location.

To categorize a collection of things, use a group object. A group is different from a container, because it denotes categorization, not physical containment. A group is also different from an item. Recall that an item acts a common description for all things in a set, whereas the things belonging to a group need not be related other than by their inclusion in the group. Use a member object to represent a thing that belongs to one or more groups.

EXAMPLE—The television network has a classification scheme for its videotapes that includes categories such as news, sports, documentary, comedy, drama, children’s, and talk show. A videotape is classified into one or more of the categories.

To model a thing constructed from other things, use an assembly object. Unlike a container and a group, an assembly cannot exist without its constituent parts. Use a part object to represent the component things that make up an assembly.

EXAMPLE—A made-to-order computer workstation is assembled from components selected by online by a customer.

An event is an interaction between people, places and things. Because they tie together the other three categories of objects, events are considered the historical glue in the object model. A simple event involves people interacting at a place with only one thing. Complex events involve multiple things and are discussed in the next section.

EXAMPLE—A mechanic inspects an automobile on a given date and time and records the results and success or failure of the inspection.

To model simple events involving only one thing, use a transaction object. Transactions are either point-in-time events that represent a momentary interaction, or they are time-interval events that occur over a long-term duration.

EXAMPLE—Common point-in-time events are orders, purchases, returns, deposits, withdrawals, arrivals, departures, shipments, and deliveries. Common time-interval events are leases, rentals, job assignments, memberships, and itineraries.

To model a point-in-time event, use a transaction that knows about a single timestamp. For a time-interval event, use a transaction that knows about the starting and the ending timestamps. History events are a special kind of time-interval event. A history event knows information about a person, place, or thing during a specified time span.

EXAMPLE—An e-commerce system assigns each of its products a price with an effective date range; for legal reasons, the price history must be retained for each product. For each assembly line, a manufacturing plant keeps a history of its products produced during a given time period. This information is used to calculate key performance measures for the line and plant.

Composite events involve people interacting at a place with one or more things. To distinguish and track each interaction with a single thing, a composite event contains smaller events, one for each thing.9 The composite event is responsible for summary information and behaviors that work across all the interacting things.

To model a composite event, use a composite transaction. Use a line item to record the interaction details for a single thing within a composite transaction. A line item is a dependent event in that it cannot exist by itself; it exists only as part of the composite transaction.

EXAMPLE—An e-commerce order is a composite transaction with a line item for each product included in the order. The line item for a single product contains the quantity ordered, shipping information, and gift wrap and gift message options.

Often an interaction between a given set of people, places, and things is followed by another interaction with some of the same people, places, and things. In general, simple events are followed by simple events, and composite events are followed by composite events.

EXAMPLE—Common follow-up events are a delivery following a shipment, an arrival at one place following a departure at another, and a return at one store branch following a sale at a different store branch.

To model an event following another event, use a follow-up transaction object. Follow-up transactions are not the same as line items. A line item records details about a thing inside a composite event. A follow-up transaction describes another event at a later time.

With the object think principles and some familiarity with the core domain objects, you are now ready to learn the fundamental patterns for object modeling. Chapter 3 presents the 12 collaboration patterns that are the fundamental building blocks for building all object models. Not only do these shape the structure of the object model, they also help extract and organize the business rules, processes, and data.

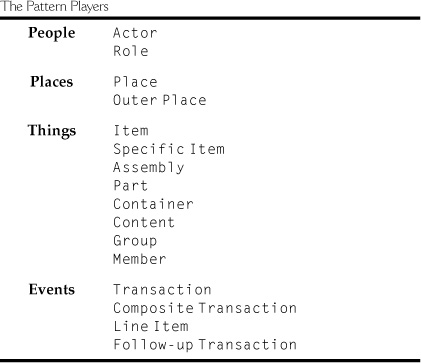

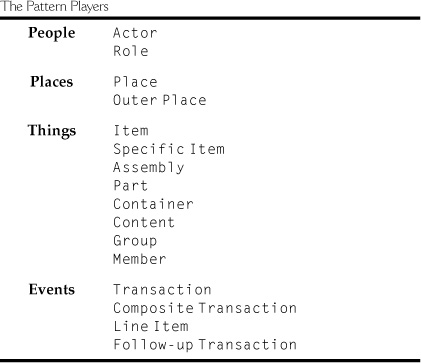

The 12 collaboration patterns are assembled from the vocabulary of objects discussed in the object selection principles. Since these objects play parts in one or more of the collaboration patterns, we call them pattern players. Table 2.1 lists the pattern players, loosely organized according to the people, place, thing, and event categories. These pattern players will be used throughout the remainder of this book.

Table 2.1. The Pattern Players