To the north of the Arctic, beyond the tundra, beyond the vast sheets of ice, even beyond the pole is a land more wonderful than a mortal’s most fanciful dream. A magical land where trees bear fruit throughout the four seasons and wheat is harvested in loaves. The land of unicorns, the abode of the gods – Odin, Tyr, Thor and Loki – known to the Norse as Asgard. The ancient Greeks called this place Hyperborea – beyond the north wind – and their boldest navigators went in search of a perfect life without toil or hunger. They never found their Hyperborea but this is the story of how we found ours.

At Denver Airport Steve and I sipped coffee and reminisced about the technicalities of our recent new route, Adrift, on El Capitan in Yosemite. The last call for boarding went by unheard during discussions about the UK Cowboy Lasso pitch and the Big Island Bivouac. And as Steve led up to the Illusion Chain our plane was thundering down the runway. After a firm telling off by the woman at the gate, we laughed at how we were so often untogether everywhere but on steep dangerous rocks, and blagged our way onto the next flight.

We had planned to try the Asgard Wall a year before. Plans rolled along haphazardly; many useless items were packed and crucial ones forgotten. As if by accident the team eventually camped together on the windswept, boulderstrewn fjord shore of Pangnirtung. We met local Innuit people and got briefed at the park headquarters on how to behave if we got attacked by a polar bear. Apparently we had to run around the bear as quick as we could as they were incredibly fast at sprint starts but slow at turning. It was a desolate place. The people used to camp on the land throughout the year but in the early sixties the Canadian government undertook a huge programme to offer prefabricated housing to all Baffin’s people here on the shores of the fiords. The loss of their traditions has created a generation gap and a new problem – unemployment and all its associated ills. In the supermarket the solvents were kept in a reinforced cage and to buy white gas we had to get a special permit from the police and take it to a sealed bunker where it was stored. Alcohol is banned, too.

Right up to the last day Simon Yates and Keith Jones had been working hard building portaledges at the Lyon Equipment factory in Dent and the day before Noel heard he had become Doctor Craine, zoologist. Just one week before I had been Steve’s apprentice in modern hard aid on the vast sheet of El Capitan’s East Face. And now, after years of picking up Doug Scott’s Big Wall Climbing and gazing at that photo, we were taking a skidoo ride across the sea ice toward Asgard. Ipeelee, our driver, sped across the ice and towed the five of us on two trailers behind. Often we would come across cracks with dark water in them and Ipeelee would either drive around them or, if they were too long, turn around, take a run up and bounce across them. But we trusted him and, anyway, we were too in awe of the landscape that we were passing. The rolling hills had turned into giant granite slabs on either side of the fjord and, up ahead, snow-capped golden spires.

We had packed 1200 pounds of lentils and bigwall gear and this had to be moved thirty miles from the fjord head to the base of the wall on the Turner Glacier. There are no porters in the Arctic, so you either carry everything yourself or use a helicopter, which we resisted. However many plans we made of how all this gear was going to be shifted, the bags themselves seemed to decide when they would arrive at the wall. Dreams of hand cracks and stemming corners had overshadowed the reality of the workload. The idea of getting two people cracking on the wall almost immediately while the others ferried loads seemed a little naive. Food was rationed from day one and our loads never weighed less than eighty pounds.

As we crossed the Arctic Circle for the fifth time in three days I heard Noel comment, “Lord, every time I see those geese I feel less and less like a vegetarian.” After the ninth day of load-carrying, our designs to trap the Arctic hare and geese had become elaborate in the extreme. The solitude was profound. Apart from a lone Catalan, who had come to attempt a solo of Mount Friga, we were the only people to have made footprints in the Auyuittuq National Park this year. Auyuittuq – ‘the land that never melts’; the name was apt. None of us had ever known such cold. As we skied up the frozen rivers of the flat-bottomed Weasel valley we wondered how on earth we could climb in such temperatures. It was obvious, we had come too early and the land needed time to warm up.

Ferocious storms came on a whim from whichever horizon they cared to as we skied up the Caribou Glacier and became stormbound at the col. After 130 miles of hideous load-carrying we decided that never had an expedition reached such depths before the mountain had even been seen. The food fantasies. The girlfriend fantasies. Warm beds, coal fires and steam pudding. We spent two days at the Caribou Col as deep snow drifted around our tents. It was a welcome rest from the constant grind.

On the morning of the thirteenth day the sun came out and we peered down the slope which led to the Turner Glacier and the face we had come to climb. It was in dangerous condition but with so little food what could we do? We couldn’t wait any longer and were desperate to see our line. Taking one of those risks that are accompanied by a silent prayer, we rappeled off the portaledge poles, lowering haulbags. The slope lay quiet and let us be. Roped together and dragging a haulbag apiece, we slithered down the glacier and our wall of dreams slowly turned to meet us. What we saw was both awesome and sickening. Huge patches of rime ice coated the face which was still very much in the shade at 5 p.m. The ice slope leading up to it was loaded and we all doubted silently whether, even if we got up the slope, it would be possible to take our hands out of our gloves to do technical aid work.

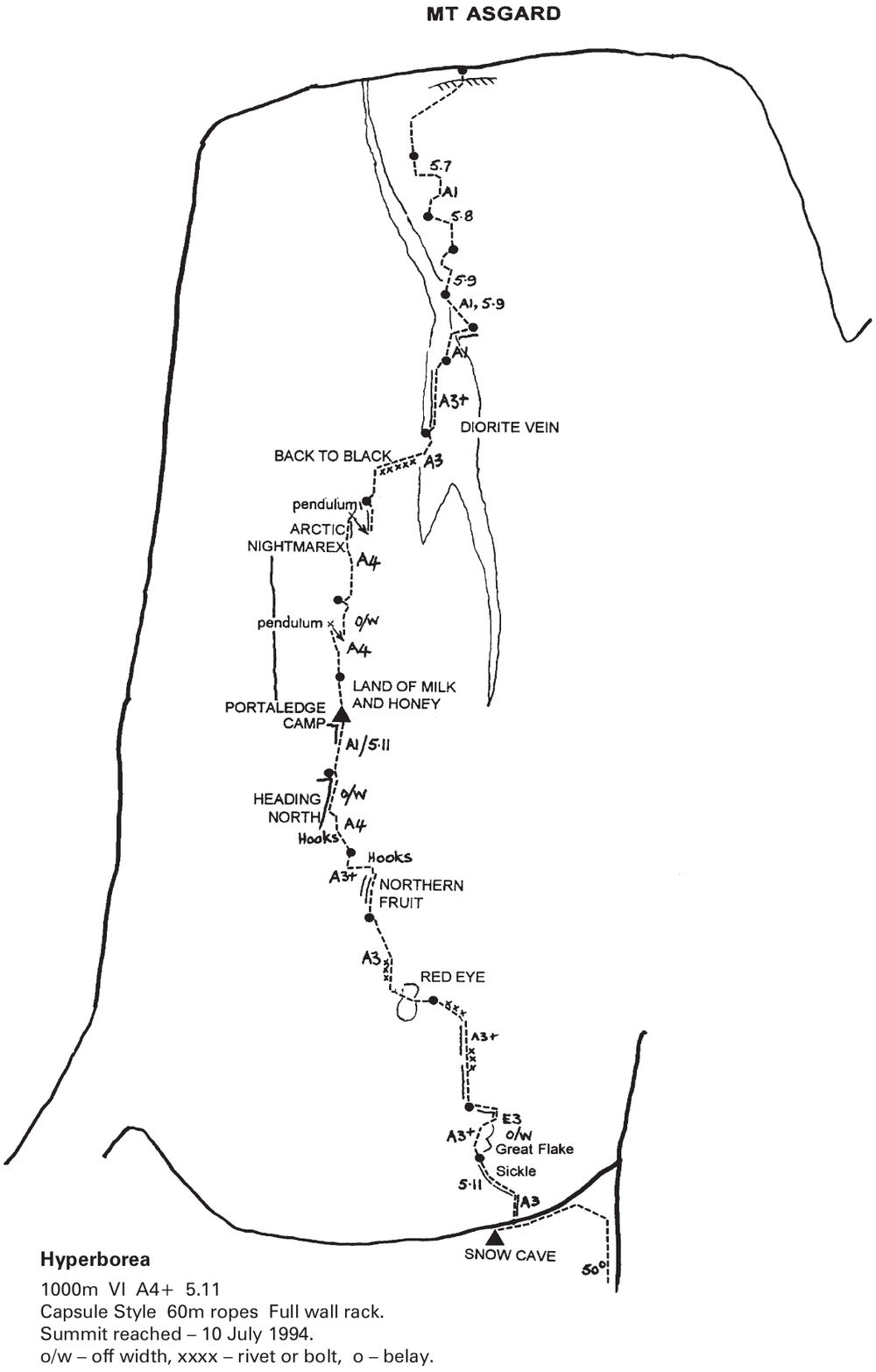

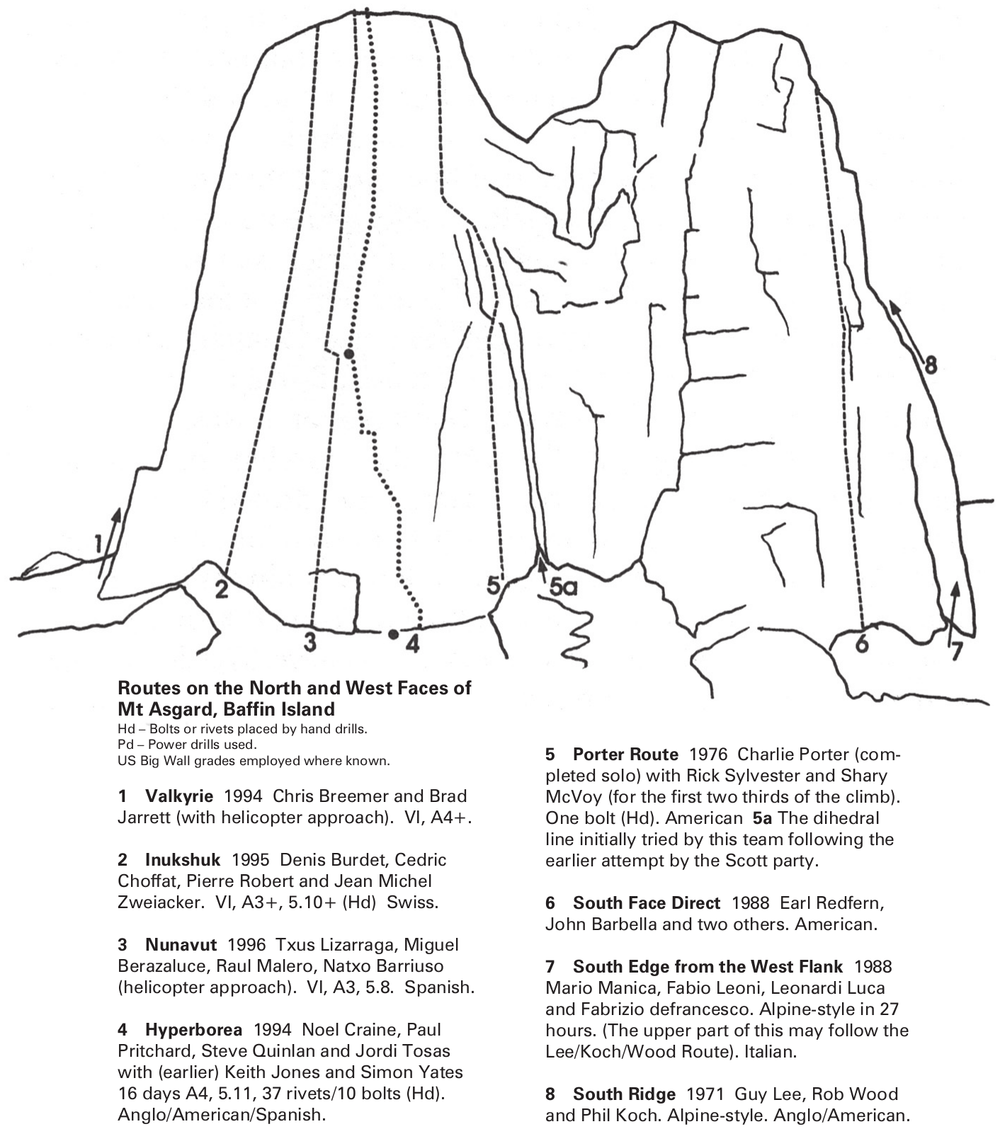

We set up camp and checked out the mountain, each impatiently awaiting his turn to look through the telescope. Panning upwards from the glacier the magnified arc traced a route: snow – scree – snow – buttress – ice – bergschrund – utterly blank granite. Working left and right the circular eye revealed only two cracks leaving the ’schrund on the whole face. This was disheartening but it made the choice simple. On the left a chimney led to the top of a pillar but above the wall blanked out. Further right a sickle-shape flake reached up to more flakes which died in mirror smooth rock. These disjointed features lured the imagination into believing that there was a way to reach the snaking corner halfway up the wall. The corner looked about five pitches long and above it a black vein of diorite led all the way to the decapitated summit. From previous experience of diorite we knew it would be loose but that loose, fractured diorite is climbable and blank granite isn’t – without drilling.

Pinned down for thirty hours in another hoolie we made a pretty good guess at how many minute squares of ripstop nylon made up the inside of my tent. The next day dawned – I use this term loosely as there is no night during the Arctic midsummer – sunny and freezing and we attempted to wade waist-deep in snow up the lower slope. Breaststroke worked but it felt like a suicide attempt and we ran away sharpish. Back at camp Noel strolled to his tent and reached for the zipper. But it wasn’t there. And neither was the tent. Luckily the tent’s prints were all over the slope and we easily tracked it down a mile away. Steve shook his head in dismay at these displays of British incompetence. That night Keith make the soundest mountaineering decision of the day and broke the rationing. A noble dahl, fit for a glass case, as Tilman would say, was followed by pears, apricots, chocolate buttons, peanuts and caramel wafers covered in custard.

The following day was pivotal. Keith and I again attempted to fix ropes on the bottom slope but, instead of improving, the slope had gotten worse. Ten-inch slabs broke off in six-foot pieces which pushed me backwards as I tried to lead the traverse. It was futile. The snow needed a week or two and a good thaw to either slide or consolidate but, by now, Keith and Simon only had a fortnight left. Bad planning on the catering front meant we hadn’t allowed for the huge appetites worked up load-carrying. We were already low on food.

The excruciating decision was made to walk the fifty miles home. We would shop and rest and stomp back in racked, ready and raring to go for another blast. And so, with our plan sorted, the pressure dropped 800 feet and we were pinned down in a blizzard for two more days. We met Jordi, our Catalan friend, on the descent. The reality of soloing a wall on Baffin had hit him like Thor’s hammer, Mjöllnir, and he had decided to bag it. Noel, Steve and I glanced sideways at each other, cogs clicking in our heads. Wouldn’t it be useful to have an extreme bigwall soloist on the team? “Hey, you come with us. Yes? Ven con nosotros.” He was delighted and joined us in the forced march to town.

After a very painful eating experience, and a farewell to Simon and Keith, we shopped and took a boat back up the now rapidly melting fjord. The boat couldn’t make it all the way through the drift ice but the walk was easier with lighter packs and after three days of carbo-loading and power-lounging, we got pinned down by ferocious weather halfway to Asgard, but began to see a pattern of two days bad then one day reasonable emerging. We walked at night on the glacier.

Jordi’s haulbag full of rope and hardware had been swept away in an avalanche. He was upset but “Es la vida.” From the base of Friga we looked across to the hourglass figure of the Scott/Hennek/Braithwaite/Nunn route on the East Face of Asgard, glowing gold in the 2 a.m. sun. This must be one of the greatest rock climbs in the world. Forty pitches all free at HVS (that’s what Doug said, but Braithwaite reckoned more like E3!) and arcing a line with the purity of the Nose of El Cap. “Why are we struggling with this pie-in-the-sky wall when we could have done numerous routes alpine-style already?” These thoughts cannot be entertained seriously.

We got back to our ditch which we referred to as base camp at 6 a.m. after twenty-eight days of shuttling loads. We now had thirteen days of food with which to attempt a big wall. Chances were slim but we work for the means and never look to an end. With no time to waste, Steve and Jordi went straight up and, finding the slope in much better condition, fixed nearly to the wall. Noel and I went up later and got a rope on the last section. The fixed lines would make it feasible for us to hump our vast amount of kit up the seventy degree ice slope to the start of the route.

At the top of the slope we discovered the perfect advance camp to work from. The glacier-polished face arose, continually over-hung, out of a huge bergschrund banked with snow. This proved to be an effective catchment area for all the dropped gear. The outer lip of the bergschrund was thick and high and a good, safe spot for a cave. It would shield us from the wind and exposure and the constant reminders of where we were. I like to hide away in the evening, go home for a few hours. Then we touched rock. It felt like a symbolic moment after thirty days of labour and the agonies of migration. We joked about planting our Survival International flag right here.

I eagerly racked up, tied in and surveyed the start of the route. It was hard aid right off the ground. The first placement was a poor micronut high up, so I taped one on the end of a ski pole and, at full stretch, fiddled it in. Earlier the team had all agreed that there should be no falls on the route, as the consequence of an injury here could be disastrous. I swarmed up to the nut and fiddled for a few minutes, trying to place a Lost Arrow. Then the nut ripped and I landed flat on my back. After the hysterical laughter had died down I finished the pitch with the help of Noel’s shoulder and a few skyhooks to bypass a three-piece suite of loose blocks. Noel moved swiftly up the next sickle pitch in one long fluid layback. This was why we were here, to climb rocks, not carry ninety-pound rucksacks up a downward-moving escalator. We fixed and came down.

With July came another terrible storm. This place was beginning to make Patagonia look like a holiday spot. But the weather cleared and the pitches crept by slowly. Beforehand we had decided on a no-drilling-on-Asgard policy but Steve, veteran of fifteen El Cap routes and new lines on Hooker and Black Canyon’s Chasm Wall, knew better. Middendorf, one of the world’s greatest wall climbers, had studied the face and commented, “Eighty holes at least.” To the Americans, riveting blank rock is acceptable and I had become accustomed to linking features on otherwise blank walls during my Yosemite trip. On El Capitan most routes use up to 200 holes. The features themselves are good sport and if you want to climb them you have to get to them somehow. This was a new way of thinking to Noel but on the fourth pitch, as the rock blanked out, he was not upset when we pulled out the Californian riveting kit and made four holes to get from one flake to the next.

We began working in shifts. One pair would push the route higher, while the other two slept. After fifteen hours or so the teams would switch. Using this system, it was possible to climb around the clock. Our 200-foot ropes meant we could really stretch the pitches and we would, overall, waste much less time building belays.

On the fifth, red-eye pitch, Noel was learning how to drill a rivet ladder, engulfed in the swirling mist. Time nudged forward, sometimes stopping altogether as I lay in the portaledge drifting into unconsciousness and, occasionally, jerked back into semi-reality to feed rope out through the Gri-Gri. I took my boots off and rubbed my feet. Time jumped ahead a little. The bombardment of ice particles continued unabated, the odd fat rogue hitting me square on as I huddled under the fly sheet. And, suddenly, for the first time, I became aware of where I was. Not in India or on the Central Tower or on Zodiac. I was on the West Face of Mount Asgard on Baffin Island in the Arctic. I threw back the fly and looked out across a marvellous panorama of ice, rock and mist in the alpenglow of midnight. It struck me that this moment was the culmination of all that had passed in my life.

There were no shortcuts to arrive at this belay and even a minute’s change on the compass could have led me a long way from here. Feed more rope out and light a cigarette. What if I had never met Mo Anthoine and he hadn’t invited me on the Gangotri trip which got me started mountaineering? What if I had never met Noel or Steve? What if I’d parapleged myself when I fell at Gogarth last year? This lack of order makes me feel wonderfully insecure.

Time stops again until Noel shouts down, tapping home another shaky rivet into soft flaky rock, “I’ll never confuse riveting with sport-climb bolting ever again.” I shout up words of encouragement. One of the four or five insincere phrases pulled out of one’s helmet during periods of intense boredom: “You’re doing great,” “Go for it,” “Yeah,” or “Nice one.” While drilling the final rivet a shard of quartz shoots out of the hole and buries itself in Noel’s eyeball. We fixed the rope pulled up from the ice slope and rapped back to the cave.

Noel’s eye swelled up and we couldn’t get the piece of rock out. He was in pain and we discussed him bailing out. We knew there was a doctor with a German team fifteen miles away in the Weasel Valley but Noel would need a guide and that would mean the end of the trip for all of us. There was too much work for two people. We laughed about his karmic price for debauching the rock but it was no joke. He might not lose his eye but the frailty of our plan was reinforced. Noel soon recovered but that piece of Asgard will forever be in his eye.

I belayed Steve on the double groove pitch. Easy nutting up the first groove led to a pendulum for a massive expanding flake. At the top of this the rock looked utterly blank. As Steve arrived at the dreaded blank section whoops of joy drifted down. At this point a knife-blade crack cheese-wires Asgard. We could follow it leftward and get toward the base of the main corner. After ten tied-off blade moves Steve headed up diagonally on circle heads and hooks and found a little foot ledge to belay on. What remained to the corner was a full pitch across loose flakes with big ledge-out potential. It was my turn to lead again.

‘Heading North’ was a sustained stretch of intense concentration and dubious mental games. It took the whole array of Rurp s, beaks, heads and hooks to cross from one expanding dinner plate to the next and, finally, with monumental rope drag, I slumped onto a fine ledge at the base of the easy looking corner. In my dehydrated and fatigued state I was convinced we had pulled off the hardest part of the route. I couldn’t have been more mistaken. Happy, I rapped off for a rest and left Jordi to belay Noel. He tried to free climb the first corner pitch but after a strong attempt reverted back to nailing. As Steve and I started the long rope climb back up for our next stint I felt a shiver and glanced up to see a black speck against the blue sky. The speck grew and I shouted to Steve, “Rock.” All I could do, stuck on a rope as I was, was to watch the rock as it spiralled for a thousand feet, sailing toward me. It’ll never hit me I thought, one person on such a massive expanse of wall. Never. But it kept coming, and then I heard it, like a buzzing sound. In the last seconds I knew it was going to hit me and I tensed my whole body and prepared for the flash that I assumed would come with death. I heard the impact, a deafening crack and then it hit me … But I was OK. It didn’t even hurt. The rock the size of a house brick had landed on a small ledge about a foot above me, almost stopped dead and the rolled onto me with no force at all. Steve and I shouted up the wall in unison, “Stuuupid bastaaards,” and from above came a meek, “Sorreee.”

Later, in the warmth of our three-roomed ice house, Noel and I discussed the tactics employed on many free wall expeditions. We could have aided the pitch, left the gear in place and redpointed it at our convenience. As with the rest of the route, we could have chosen to free whichever pitch we felt like along the line of fixed rope. We had looked at Proboscis in The Cirque of the Unclimbables and were saddened to hear of its rap-bolting by two American friends. And the retro-bolting of the Pan-American route on El Gran Trono Blanco and walls in Yosemite. We decided that the essence of wall climbing was to get from the bottom to the top as efficiently as possible which, in the mountains, means as quickly as possible. But speed does not go hand in hand with redpointing. Most of Yosemite’s big walls have taken the best part of a year to free. Free cruising is definitely less time-consuming than aid climbing but not necessarily more enjoyable. We didn’t want to go back down and free lower pitches. We were looking upwards only and, besides, the hard aid opened up new doors of fear and excitement. Once the pins were in place we could have freed the first pitch at 5.12c. We would have got kudos of a hard free rating on a big wall but felt this would have made a mockery out of Asgard.

So with six days’ food left it was imperative we should free what we could, dog what we couldn’t and nail the impossible. Big wall free climbing does have an exciting future, though. The Salathe Wall of El Capitan and the Slovene route on Nameless Tower will get on-sight ascents but, to date, have any of these big wall media events truly been freed? (Since writing this Lynn Hill has made a fantastic one-day ascent of the Nose on El Capitan). I must admit it wasn’t a big issue for us.4

We felt like the only people in the Arctic but presently four dots appeared on the glacier below. They left their haulbags at Asgard’s feet and returned the next day with more loads. We knew they had come to try the wall but we had to bury any intrusion we felt. After all, this was one of the most sought-after unclimbed walls in the world. Perhaps it was the German team who we met on our shopping trip to Pangnirtung. They had with them a Hilti power drill and a twenty-kilo car battery. They wanted to make a route “that everyone could enjoy”. We despaired at the thought of the noise pollution on our wall and future queues of climbers with only a rack of quickdraws. But use of the Hilti seems almost standard practice now. In 1992, whilst on the Central Tower of Paine, we happened upon machine-drilled bolts on easy ground just two pitches from the top on the German route.

The dots grew until they became full-sized Swiss climbers who had arrived to try our line. They were not too put out, though. It’s a big face with lots of room. They would try further left. Steve set off on the eighth monster pitch, a snaking openbook only just split by a fragile knife-blade fissure. The fissure disappeared after fifteen bodylengths and reappeared four bodylengths to the right at a gross, loose, fat crack. Again the cold and boredom of my belay duty produced a transcendental state. The hours pass, falling with the avalanches which crash down the slabs of Loki opposite. It is night-time and the sun, weak yellow disc that it is, warms my face if I look square into it and shut my eyes. It coasts along the western horizon throughout the night rolling up and down the profiles of the mountain ridges and casting long shadows to the north, then east and south by morning. Now and again the ice falls. A small chip floats by and warns that we are in for a barrage. Slightly bigger pieces follow and then some very big chunks. Bugger transcendental states, now’s the time to get cracking to avoid being taken out. As the ice blocks spin through the air they make the fearful whirr of aboriginal instruments that warn of their approach. The Inuit have a word for this kind of fear in the face of unpredictable violence, such as having to cross thin sea ice. The word is kappia.

Steve made the top of the first crack and, again, had to place two rivets from which he could make a pendulum into the fat crack. I feel here that, for the British reader at least, I should outline the distinction between riveting and bolting, for they are two very different things. Both require the drilling of a hole but rivets – being only a half inch long by a quarter inch diameter threaded nut – are body weight pieces for upward movement only. They cannot be considered as protection should one fall. After five or six hours Steve had built another fabulously exposed belay on blank over-hanging rock. As I cleaned the pitch the portaledge flew up the face like a giant black bird and at 3 a.m. I led off up the last rope-length in the open corner. Miles of brittle dinnerplating placements led to a disgusting diorite band about seventy foot thick. The diorite had the consistency of stale cake and would not be subdued by nailing. Only very silent nutting, kappia again, would get us through this delicate section which we named the Arctic Nightmare.

After twelve long body weight moves I found myself equalised on an RP2 and an RP3 behind a creaking cupboard door. Above was no place for a nut, so I tapped in an Arrow. Standing up in my aider I began to scrape a Walnut placement in the cake high above me. I heard a faint sound like the sounds you can hear when trying not to wake sleeping friends. The audible sound of taking the foil top off a milk bottle or turning a door handle. The Arrow slowly turns its hand from nine o’clock to twelve and the side of the crack falls off. The peg lands in my lap at the precise moment my right boot contacts a tiny edge and my fingers grasp the cupboard door. The door stays shut and I timidly weight the RPs. After some deep breaths and vivid pictures of home, friends and the future, I shout down for the bolt kit. In this soft muck even a bolt did not fill me with the warmth of security but it sufficed to finish the pitch.

At midday, after twenty hours of work, we slid down and switched with Noel and Jordi. They attempted the next pitch but became lost in a sea of dead calm rock. After some sleep Steve and I began work hauling a camp up the wall. It had taken six hours to climb the ropes to our highpoint, so we decided it was time to live on the wall. We had been putting this off as long as possible because our home-made portaledges – made out of a Lyon Equipment display for hanging clothes on – kept breaking whenever we sat on them, even at ground level. Keith and Simon had tested them for a few minutes, bouncing up and down in the factory. We also hauled food for five days, sleeping gear and a plastic barrel full of water. After the first night on the wall Noel and I christened our ledge the Potato Chip because of the pronounced twist it took on whenever we lay in it. The whole night would be spent fighting to stay in the thing.

In the morning we were woken by the throbbing sound of helicopter blades. It was the Californians, Brad Jarrett and Chris Breemer. We had met in Yosemite and wished each other luck. The helicopter settled them right below the mountain and within seconds had flown away, leaving them shocked on the glacier. We screamed to each other as Americans do and I pondered on what different memories we would each have of the approach, fantastic aerial views against a month of grind. I wouldn’t trade places. I went up with Noel and finished what he and Jordi had started the day before. Our big wall soloist, who was going to lead all the hard pitches for us, was having a considerable amount of trouble even on the easiest pitches. In Spain he had led A5 but here he was finding A2 difficult. But he was good company and we were glad for his sake that he was with us and not trying to solo Friga.

This pitch was the key, linking the snaking corner to the diorite vein which led to the summit, and was sorted with hooks and heads and six rivets in blank rock. On the last move of the pitch I placed a fish hook and stood up to peruse the belay situation. The hook ripped straight through the soft rock and I was left hanging from my arms more petrified than the rock. After shouting repeatedly to Noel – after six hours your belayer can often be asleep – I let go and took the whipper. A blade held and I climbed to the belay with more caution.

On the raps back to the ledges we held a hanging conference with the other two and decided that Noel and I would get four or five hours’ shuteye and come back up. From now on we would go alpine-style to the summit. The weather had been gorgeous for a day or two and we were all aware that every good day was a day nearer the impending storm. Everything was going to plan. This just doesn’t happen mountain climbing. After filling our faces with mash potato and Parmesan and trying to force down Noel’s attempt at baking a coffee and walnut cake, a valiant effort in a portaledge, we rested a little and clamped back onto the lines. Steve’s pitch was hard and soft but went steadily and, above, after eleven 200-foot pitches, the rock stopped being overhanging. We raced up the rope and congregated on a snowy ledge.

From here we could look straight down Charlie Porter’s line. It is the only line on this side of the mountain, a superb corner prising open the south-west edge of the North summit. Porter was first to climb many of Yosemite’s hard classics in the seventies and his presence there was a driving force in raising the standards of the day. The Shield and Mescalito and his solo of Zodiac were milestones in big walling but the crowds got too much for Porter and he went north in ’79 in search of total solitude. He found it on Asgard in the form of an epic and painful adventure. Utterly alone he climbed the corner during two weeks of rain. When he got back down to earth he had to cut his boots from his swollen feet and crawl the thirty miles to the fjord-head. There he met some Inuit who gave him Coca-Cola! Soon after completing this magnificent climb Porter gave up big walling and holed up in Chile to work on an Aqua Culture project.

The sun blazed and we climbed as fast as a party of four could. Some mixed pitches and some free pitches on superb granite fell behind us. All the time the top was in sight. On Asgard there is no tedium of one false summit after another, you just slap the top and mantelshelf! I led a slow aid pitch and belayed twenty feet below the rim to give Noel the thrill of topping out first. We had to be very controlled and precise here as we were all getting extremely tired. Noel led up and free climbed through the summit overhang. By the time we had all jugged up it was 10 p.m. and the sun was shining low and bright from the west. It was an emotional time and after the handshakes and hugs we each wandered off on our own about the flat white field above the Arctic. To at last look east was special. Ranks of unclimbed Thors and Asgards marched deep into the distance. Out west the Penny Icecap shimmered in the haze. Noel shed a tear as Steve took photos in all directions.

Jordi spotted his avalanched haulbag at the base of Friga and I took my first shit in three days. As I squatted, I giggled at how lucky we were. If the bad weather had continued just a day or two longer we would have used all our food and run out of time, but the window opened and let us in.

After a couple of hours on top and a good feed we carefully rapped back down the seven pitches to our fixed rope and cleaned that down to our ledge camp. We arrived at 3 a.m.; for Steve and Jordi it had been thirty-six hours of non-stop work. We had no trouble collapsing into a twelve-hour coma. When we awoke the weather was showing signs of change. A mackerel sky was shunting in from the west. So with battered, throbbing hands we began rappeling and lowering our kit down the face and staggered in one push all the way to base camp. The glacier had become horrifically soft and even on skis we sank to our knees.

After sleeping some and striking camp we shouted good luck to the other climbers and waddled out under hundred-pound sacks down the Turner Glacier. Black clouds boiled and poured over Loki. We tried to hurry but the storm had no trouble catching us. We were secretly glad that the other climbers were now experiencing some real Baffin weather. It would have been too much if our Californian friends had, after flying in by helicopter, got weeks of Mediterranean sunshine.

The long walk out is a blur. We fell repeatedly under our loads and I had the hallucinations I had known before that come at the end of an epic climb. The electric colours of the lichens and mosses made me stand, sway and stare but the feeling of an invisible presence and the voices were disturbing.

We met kind people who gave us morsels of food and at 10.30 one evening we met a small boat at the fjord-head and were whisked away toward civilisation. Noah and Joaby gave us tea, cake and cigarettes and we could only laugh as our boat stuck fast in drift ice only one mile from town. But we got in and that night were given real beds and fresh salmon. The people of Pangnirtung were celebrating because they had just caught their first beluga whale of the season. We joined in the jollity and entered the Inuit Olympics. After a long battle I won the stick jumping contest, as young mothers looked on with their babies in the hoods of their sealskin coats. And they all roared with laughter as Noel managed to whip himself on the backside with a twelve-foot bull-whip.

I can’t remember on which long belay session it was, but I can recall the cold creeping onto the portaledge, numbing my feet, my legs and cradling my mind with torpor. I had drifted back to our desert trip only a couple of months before. Standing Rock, Shiprock, Monster Tower. We had climbed loads of towers and doing that allowed us to study the desert, from a distance, from up close and, unique to climbers and aviators, from above. The desert, the tundra and the ice of the poles may be the only places on earth where, at a glance, there seems to be nothing. But if you search closely the wealth of the land becomes apparent. There are vast forests but Arctic willow is only three inches high. The animals are so well camouflaged that they are difficult to detect even up close. Everything needs intense study, including the rock and especially if you are aid climbing. Examining the skin of the rock and trying to puncture it, not wholly unlike a sheep tick.

The history of the land is part of its wealth. The people who have moved upon it, the creatures that have evolved to live there, the angle of light that has pulled the same shadows from the boulders and pinnacles for thousands of years. During my cold meditations I too felt a part of the land and, by leaving our invisible mark, maybe we will always be a part of it.

4 Editor's note, 2012: Impressive big wall free climbs have followed the original publication of Deep Play in 1997. In Yosemite, Leo Houlding and Patch Hammond almost onsighted the route El Nino (5.13c) only days after the first ascent, and Leo has added other free climbs to the Valley in fine style. Tommy Caldwell and the Huber brothers, Alex and Thomas, are also responsible for many of Yosemite's new free climbs. The Hubers also freed the Wolfgang Güllich/Kurt Albert route Eternal Flame on Trango (Nameless) Tower in 2009.