133

At Farleigh House, the morning’s post was distributed during breakfast in the dining room, an out-building of recent construction, its walls lined with grey, pleasingly crumbly asbestos, easily extractable for playing with.

Once a week I would receive a chatty letter from my mother, talking about goings-on at home and ending ‘Not long now until half-term!’, or ‘Not long now until the holidays!’

Parcels were a rarity, largely restricted to my birthday, early in the summer term, but in the holidays I had pre-ordered Abbey Road from a record shop in my home town of Dorking. For a little bit extra, to cover postage and packing, they agreed to send it to me at Farleigh House. I can now date its arrival to 27 September 1969, the day after its national release. I remember my excitement as I took it out of its stiff brown cardboard envelope with the other boys looking on, not so much amazed as bemused. Only a handful had any interest in pop music – most of them preferred football, yo-yos, the Beezer or the Eagle, making dodecahedrons out of card, or constructing Airfix models of Spitfires and Lancaster bombers.

‘What’s that then?’ asked the Latin master, Mr Needham, as I sat there, perusing the cover of Abbey Road. ‘Top of the Flops?’ He liked speaking in puns: he called the Everett brothers ‘Ever Wet’, and the Brown brothers ‘Hovis’, after the brown-bread slogan: ‘Don’t Say Brown, Say Hovis’.

During the summer term I had attempted to get myself into Mr Needham’s good books by pointing out that both Status Quo and Procul Harum had Latin names. Misreading my level of interest, he went on at tedious length about the meaning of status quo, and pedantically pointed out that if procul harum meant anything at all, it meant ‘at this’, which meant nothing at all. I wished I’d never mentioned it.

sjvinyl/Alamy Stock Photo

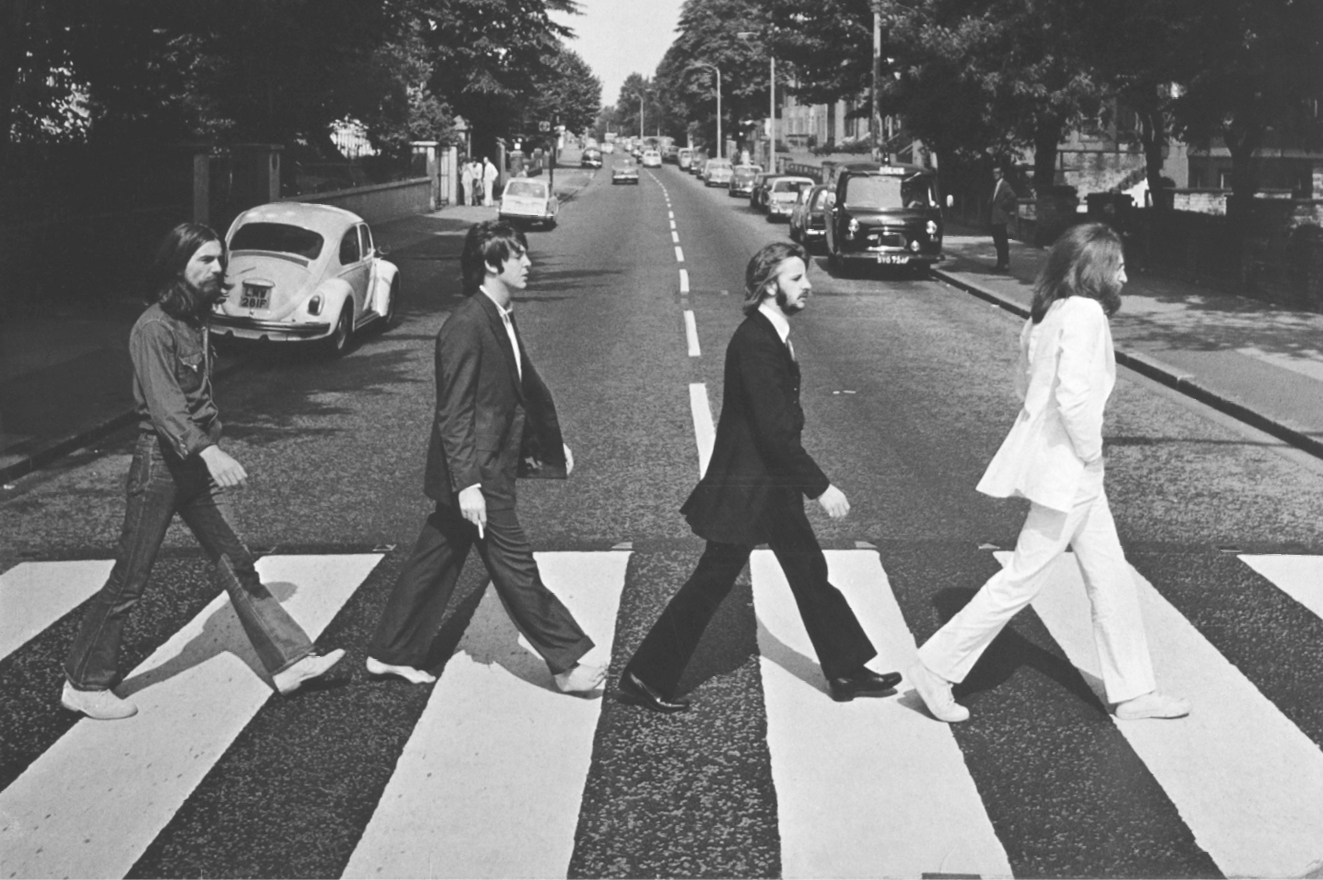

On first setting eyes on the cover of Abbey Road, I felt a keen sense of disappointment. The shiny white sleeve of The White Album had looked grand and luxurious, and came with all those bits and pieces inside – the colour photos, the poster which opened to reveal yet more photos and all the lyrics on the other side. Sgt. Pepper, too, had all those different characters standing as if for a sort of school photograph on the front, and the gatefold sleeve, and the cut-outs, and the lyrics in rivetingly small print on the back. But the front cover of Abbey Road just seemed dull – the four Beatles walking over a zebra crossing as though it were a bit of a chore, not even bothering to smile or look at the camera or lark about, and generally looking as if they couldn’t be arsed. And the back was even duller: a dreary road sign saying ABBEY ROAD, plus something out of focus and blue swishing past. Furthermore, it was just a single sleeve, with no extras tucked inside: no lyrics, no cut-outs, no photos. Surely, with all their money, the Beatles could have come up with something better than this?1

But posterity can’t be second-guessed. As with the Mona Lisa and the Eiffel Tower and Her Majesty, time can render the dull iconic. In 2010 the British government awarded Grade II listed status to the zebra crossing on Abbey Road, on account of its ‘cultural and historical importance’. And the markets took it seriously too: in 2014 a limited edition of six prints of the various Beatles/Abbey Road photographs, numbered and signed by the photographer, sold at auction for £180,000.

It is hard to think of an album cover more frequently imitated. Booker T and the MGs, Benny Hill, George Benson, Sesame Street, the Community of St Saviour’s Monastery Jerusalem, Ivor Biggun, the King’s Singers, the Red Hot Chilli Peppers, Jive Bunny, Blur and many more have released albums with cod-Abbey Road covers. The only time the Simpsons were featured on the cover of Rolling Stone it was with Lisa (as George), Bart (Paul), Marge (Ringo) and Homer (John) on the Abbey Road zebra crossing.2 Paul McCartney parodied the Abbey Road cover for his 1993 solo album Paul is Live, on the cover of which he is pictured with one leg high in the air, crossing the road with his Old English sheepdog Arrow.3

At first, the basic details of the shoot appear relatively straightforward. At 11.35 a.m. on Friday, 8 August 1969 the four Beatles spent ten minutes being photographed walking across the Abbey Road zebra crossing by Iain Macmillan. But like virtually everything to do with the Beatles, even this is open to question. There are, for instance, ongoing arguments as to the exact time of the shoot: Mark Lewisohn and Barry Miles pin it to 11.35 a.m., but The Beatles Bible says it was 10 a.m., and Bob Spitz says it was ‘some time after 10.00 a.m.’.

Most online discussion revolves around the people visible in the background, comparing the different photographs taken by Macmillan over the ten-minute period. The website of The Daily Beatle (‘News and articles about the Beatles since 2008’) features a long discussion about who they were, or who they might have been. The webmaster devotes a lot of attention to what he calls ‘Mystery man’ in a brown jacket, standing on the right, with his arms crossed. In another photo ‘Mystery man’ is still there, but has moved further away, and now shares the pavement with a woman in a red sweater who is looking directly at the camera.

‘Here’s where it gets interesting,’ says the webmaster, optimistically. ‘You have to look very, very carefully on the left pavement to spot her, but in the closest gateway, just behind the Beetle, is a young woman in a purple top. This is her first appearance, but she is present in three of the six frames – just one fewer appearances than “Mystery man”.’ In a fourth photograph ‘There’s no sign of “Mystery man” but there is another man in a white shirt, striding with some purpose, walking towards the camera.’

And so to photograph number five, picked for the cover because it was the only one which had the Beatles walking in step. ‘On the left pavement, further back, stand three decorators, subsequently identified as Alan Flanagan, Steve Millwood and Derek Seagrove … There is no sign of the mysterious girl in the purple top.’ A Mrs N.C. Seagrove writes that Derek is her husband; together with Flanagan and Millwood he was coming back from a lunch break when the picture was taken. ‘They hung around just to be nosy. Derek thought if it was used, he and his mates would be edited out.’

More controversy centres around the ‘Mystery man’, who stands next to a police van. ‘In February 2008, news was that Florida resident Paul Cole, the man beside the police van, had died, aged ninety-three. But was he really that man? I don’t think so, and here’s why.’ In 2004 Paul Cole claimed to have been in that spot, waiting for his wife, who was visiting a nearby museum. He said he had been starting a conversation with the driver of the police van when he spotted the Beatles. ‘A bunch of kooks, I called them, because they were rather radical-looking at that time. You didn’t walk around in London barefoot.’ A year later, his wife, a church organist, had been given Abbey Road to play at a wedding. ‘I saw it resting against her keyboard and I said, “Hey! It’s those four kooks! That’s me in there!”’ Cole had never listened to the album, though he had heard one or two Beatles songs. ‘It’s not my kind of thing. I prefer classical music.’

But the webmaster casts doubt on Cole’s claims: ‘There’s no museum in that part of Abbey Road. The police van was a late arrival to the photo session, as evidenced by the previous photos, so Paul Cole can’t have had a conversation prior to the Beatles arriving at the scene.’ He concludes that Paul Cole was a fraud. But is he wrong? There certainly was a museum nearby – the Ben Uri Gallery, dedicated to the work of émigré artists. Furthermore, Cole only claimed to have been starting a conversation with the police driver when his attention was caught by the Beatles crossing the road. And he was remembering events from thirty-five years before: there were bound to be inconsistencies.

‘I have heard stories about people claiming to be or to know “the man on the cover” for as long as I have been a Beatles fan,’ writes the webmaster. ‘One of them supposedly was a gay man who died in the seventies.’ He then quotes someone called Jo Pool, who writes, ‘As soon as I saw the cover, I shouted, “That’s my brother, Tony.” Tony Staples was thirty-three and six foot four inches tall. On the day in question he was on his way to work as an administrative secretary for the National Farmers’ Union.’ But is this true? To my mind he looks older than thirty-three, and it seems unlikely that a secretary at the NFU would be leaning quite so nonchalantly against a wall at ten or eleven in the morning while ‘on his way to work’.

The mysteries do not end there. Who is the woman in the blue dress on the back cover? Some bloggers seem convinced it is Jane Asher, though they offer no evidence. Others, tired of debating the figures on the front or back covers, seek to extend the parameters of their inquiries to those who were somewhere else. ‘Does anyone know the name of the police officer who held up traffic while the photo was taken, or know anything about him?’ asks Randy Ervin. But his question draws a blank.

1 Little did I know it at the time, but they had in fact been planning something much more ambitious. After toying with the titles ‘Four in the Bar’ or ‘All Good Children Go to Heaven’, they had decided to call the album ‘Everest’, with a cover photo of the four Beatles climbing the highest mountain in the world. Paul was excited by the idea of a trip to Tibet, but John and George kept changing their minds, and Ringo was dead against it, as foreign food disagreed with him. With the deadline approaching, John and George sided with Ringo. According to Geoff Emerick, a frustrated Paul said, ‘Well, if we’re not going to name it “Everest” and pose for the cover in Tibet, where are we going to go?’ To which Ringo replied, half-jokingly, ‘Fuck it. Let’s just step outside and call it “Abbey Road”.’

2 Indeed, the cover of my own little book 1966 and All That (2005), an update of the classic 1066 and All That, featured a Ken Pyne pastiche of Abbey Road, with the parts of John, Ringo, Paul and George being taken, respectively, by Bobby Charlton, the Queen Mother (on a Zimmer frame), Sid Vicious and Winston Churchill.

3 Offspring of the more famous Martha.