“I’m obsessed with Germany. For Denmark, it’s a very big neighbor. Germany is a symbol. It is Europe.”1 With this formulation, or perhaps we should call it a confession, director Lars von Trier describes his film Zentropa in terms of an individual and a perceived national relationship to the spaces of Denmark, Germany, and Europe. What is striking about this avowedly personal commentary is how unself-consciously it lays bare the tensions involved in the “European film.” That there are national positions to be taken up can be seen from the response of the French critic who quotes this interview: he takes immediate issue with what he calls von Trier’s “provincial timidity” and points out that Germany is not, after all, coextensive with Europe. At one level, this exchange provides a humorous microcosm of European stereotypes, pitting the Dane, whose independent stance toward Europe belies a fear of German domination, against the French sense of national preeminence. More seriously, though, the series of elisions that structure von Trier’s remark illustrate the difficulty of reading Zentropa in terms of nation. For while Underground described an impossible national space, and while it worked on the difficult connection of that national space to the larger space of Europe, the concept of nation was nonetheless a central point of reference. In Zentropa, by contrast, there is no simple relationship to nation. As von Trier’s words suggest in their uneasy movement from discours to histoire and from Germany through Denmark to Europe, the meanings of national and supranational spaces can become slippery.

Zentropa was released internationally in 1991, a year after the reunification of Germany, and a year before the Maastricht Treaty was signed by the nations of the European Union. At first sight, the film seems distant from these contemporary concerns: its story is set in 1945, and its art-cinematic emphasis on style and form deny any obvious social engagement. The story, moreover, is not overtly about Europe but about Germany specifically. Leopold Kessler is a young German-American who comes to Germany in 1945 in a naïve attempt to help the country rebuild. Through family connections, he gets a civilian job working on the railways, where he meets and falls in love with Katharina Hartmann, the daughter of the owner of the rail company Zentropa. But Kate turns out to be a Nazi sympathizer, a former member of the Werewolf terrorist group, and through her, Leo becomes unwillingly embroiled in a terrorist plot. He ends up trapped on a train he has helped to blow up, and the film ends as he drowns, swallowed by the dangerous space of postwar Germany. However, the murky spaces of Germany in 1945 are not unconnected to the concerns of the “new Europe,” and we can read Zentropa’s historical image in terms of European space. This chapter examines how the film stages European-ness as a textual problem, constructing a relationship between the spectacular and the geopolitical. This relationship, I argue, works to overlay 1945 with 1991 and to map cinematographic space onto or into the psychic space of Europe.

The European Film

As I argued in chapter 3, the coproduction centers an inherent tension between the discourses of national art cinemas and those of international cooperation. Most coproduced films resolve this dilemma both textually and extratextually in much the same way—by associating both the subject of the film and its makers with one country. Usually, this involves an auteur-based claim on nationality, although sometimes it may be the star actor, location, or literary source that bases the film’s claim on a national culture.2 Zentropa, though, makes none of these claims, or at least not with any clarity. Lars von Trier is Danish, but the film is set in Germany and does not pay any obvious attention to Danish national culture. Dialogue is in English and German. The actors are variously Canadian, Swedish, and German, and the producers are just as diverse. In his industrial analysis of the film, Terry Illot characterizes its potential audience as “European art-house” and concludes that “Zentropa is that rare thing, a genuinely European film. Although Danish in origin, the film was made by Swedish, Danish, German, and French partners, filmed in English and German and shot partly in Poland.”3

Leaving aside the popular connotations of the Europudding, this international production history suggests problems of both enunciation and address: Whose stories can a European film tell, and to whom should it speak? An apparently simple answer to the second question is offered by the film’s producers, who claim that “the film was meant to appeal to the European audience: the Scandinavians, the Germans and the French.”4 Here we find precisely the kind of definition of Europe that the film in fact works to problematize, but has become politically and culturally dominant in the years since 1945. Europe in this rhetoric is northern and western Europe, just as, for von Trier, Germany is Europe. The broad notion of a “European audience” telescopes before our eyes. As this ideologically loaded example shows, the location of “Europe” is not simply an economic problem for a film with no clearly defined domestic market. I shall return to the implications of this western view of the continent, but for the moment the slippages we can already trace between Europe and western Europe, and between Germany and Europe, are most important. This telescoping effect—precisely the one by which von Trier is able to come to the conclusion that Germany is Europe—leads us to the second question raised by the film’s internationality: How does it textualize national and international space?

Pierre Sorlin has argued that while there was an upsurge in historical films in Europe in the 1980s, very few of those films treat the history of a country other than their own.5 (And this argument need not be limited to the 1980s, for historical films as a genre have at all periods tended to stick with nationally constituted histories.)6 Thus, for example, French films such as Une affaire de femmes (Chabrol, 1988) and Chocolat deal with French wartime and colonial history, and the Yugoslav partisan films endlessly retread stories of the emergent nation. This logic presents a problem for a “genuinely European film.” The question becomes: Which country’s history should an international film recount? Zentropa does not base its narrative on the Danish history that an auteurist approach would suggest, nor does it construct a transnational European object.7 Instead, in Sorlin’s terms, it takes place in a foreign country and structures its narrative around that country’s specific history. It is a film about a nation, but not a national film. This structure already suggests questions about ownership: Whose history is this? But this historical and geographical location is not merely a foreign one (as far as the coproduced film goes) but is a space as overdetermined in international film history as in European politics: Germany, 1945. Year Zero.

This choice of location immediately complicates any claim on nationality: although postwar occupied Germany is a unique and complex case, its influence refracts across much of the postwar European order. World War II and the battle against Nazism provided the foundation for the many ideological struggles of the second half of the twentieth century, and issues from the defeats of the West European Left to the beginnings of the Cold War and the movement for European union can be traced back to the immediate postwar German question. The fate of Germany’s occupied space formed the nascent order’s most pressing challenge, and the political debate over how to punish the Nazi past was rapidly overtaken by the fresh problem of the country’s de facto partition. The crucial period from 1945 to 1948—which in Italy covers the time from the end of the war to the decisive victory of the Christian Democrats and which in Yugoslavia marks the new nation’s construction and then expulsion from the Cominform—in Germany describes a time of suspension: between Nazism and partition, and between war and Cold War. During this time, Germany was a nation only by default, with no government other than that imposed by the various Allied authorities and an entirely uncertain future. Thus, the narrative space of Zentropa is already not-quite-national. In Zentropa, German space is not legible as national and does not primarily evoke a traditional national history; rather, Germany stands in a metonymic relation to the troubled political and historical spaces of something called “Europe.”

“Go Deeper into Europa”

The first site of metonymy the film creates is a gap between the voice-over and the image—more accurately, the voice-over and the diegesis. Zentropa opens with a lengthy sequence in which a traveling shot moves rapidly along a train track at night, while in voice-over we hear the monotonous countdown of a hypnotist (played by Max von Sydow), instructing an unseen subject that on the count of ten, he will be in “Europa.” Since the next scene depicts Leo’s arrival in Germany, the spectator quickly realizes that Leo is the hypnotized subject and “Europa” is the narrative’s location. But there is an immediate ambiguity here. The hypnotist exhorts Leo to go “deeper into Europa,” and his words do not take Europe merely as object but connote internationality in their form. He speaks English, yet says “Europa,” which is Italian or Spanish, and his voice carries a Scandinavian accent. By contrast, the narrative is not taking place in some vague Europa but in a specific Germany, and the image that matches this voice-over is a concrete one of train tracks. Leo, the addressee, is located in a material place on a route between specifically listed German towns. Further, the relationship between the voice-over and the diegesis in which Leo’s narrative takes place is temporally irresolvable. Since Leo dies at the end of the film, there is no future time in which he could be hypnotized to recall his time in Germany. Thus, the space of the voice-over (in which Leo is in “Europa”) and the space of the diegesis (in which Leo is in “Germany”) are contiguous but irreconcilable. Germany cannot simply signify as part of Europe in a naturalistic manner, and the two terms are brought into a tense proximity.

This example makes clear the cinematic distinction between a national space—which can be represented visually, as in the idea of the national landscape—and the international space of Europe, which cannot be. “Germany” appears to exist at the level of the image (seen in rail yards, houses, fields), but “Europa” is possible only through the disembodied voice. European space is invisible, existing as a political idea but not as a coherent location. While there are engrained histories of representation that underwrite the cinematic conjuration of Italy, of Yugoslavia, or of Germany, there is no image that, on a purely visual level, can claim to transcend those national signifiers to represent the continent directly. Any possible image would in the first place be national, and the connotation of European-ness could be of only a second order.8 Thus, for Zentropa to speak as a European film, it must go through the national but at the same time must unhinge cinematic space from its national connotations and refigure it as European. For Germany to become Europa, German space must be denationalized. And this cinematic imperative to denationalize German space dovetails with the narrative location of the film in zoned and occupied—that is, denationalized—postwar Germany. It is in this brief period of national incoherence that the problem of European space can come into view.

Zentropa tropes the relationship of national to European space insistently, circling the problem of a terrain that is historically precise and yet not visibly marked and in which one element slides into the other, refusing clear and proper boundaries. The clearest textual condensation of this problem is the train, which should be a machine for the rational mapping of space but which instead works to destabilize any coherent narrative space. Thus, while Leo spends a good deal of time traveling across Germany, he mostly remains on the train, never able to enter the space of the country directly. Within the discourse of train travel, the film schematizes German space both visually and aurally: through the list of destinations heard in voice-over while Leo travels, through the rail map of Germany that he stands in front of in an early scene, and through the model train set we see in Max Hartmann’s attic. Indirect representations of German space multiply, but the thing itself becomes more and more attenuated. Just as Leo is a hypnotized subject and not a direct participant, so the figure of the train allows only a mediated relationship to a European landscape that is never actually reached. Like Leopold, the film is never really there.

Zentropa German space is mapped graphically.

Furthermore, the objectivity of the train itself is brought into question. Leo’s uncle, the railway worker, confesses his fear that sometimes the train changes direction and finds itself going backward instead of forward. Leo rejects this fear as irrational and offers a scientific explanation for what he interprets as an optical illusion. However, the climactic scene—following Leo’s defusing of the bomb that he himself had set on the train—appears to prove his uncle right after all. Throughout the time that the bomb has been aboard, there has been a series of cutaways showing both the train and its relationship to the Neuwied bridge. First, we see the bridge in the distance, from Leo’s point of view on the train, and then several shots (not point of view) showing the train approaching and then crossing the bridge. These shots, we can presume, provide a metadiscursive view of where the train really is. But after the train has crossed the bridge and Leo has defused the bomb, and after some intervening sequences dealing with Leo’s examination and Katharina’s arrest, Leo looks out the window and sees, once again, the same bridge approach. Immediately after his realization, there is a cutaway to a long shot of the train, which is, irrationally, once again crossing the same bridge, and from the same direction. Space is repeating itself, and with this objective proof of impossibility, the train blows up, demonstrating a narrative as well as a spatial disjuncture.

Zentropa The model railway repeats German space in miniature.

That an impossible German space should be figured by a train also has a historical precedent. Timothy Garton Ash writes that the concept of Mitteleuropa, a middle Europe rather than an eastern or a western Europe, became an impossibility during the postwar years. Not only did the splitting of Europe into two rigid spheres preclude any cultural sense of middle Europe, but in Germany the term was tainted by associations with its previous use by the Nazis. The word, he writes, lived on “only as a ghostly Mitropa on the dining cars of the Deutsche Reichsbahn.”9 Thus, the concept of a middle Europe existed only on trains, in an impossible space that had no political reality in a Germany split into East and West, but only, in Garton Ash’s apt formulation, a spectral reality in the non-place of the train. In the wake of reunification, he argues that the idea of central Europe began to return as a political and cultural discourse, and it is this ghost, I think, that Zentropa projects onto its postwar trains. Mitropa is, after all, very close to Zentropa, and like the real-life railway’s trace of a lost Mitteleuropa, the film’s trains map a space that does not really exist.

The idea of German space as a void resonates with the trou noir (black hole) that Thierry Jousse finds structural to Zentropa.10 In his article “The Voids of Berlin,” Andreas Huyssen relates a discussion of the post-Wall Berlin architecture debate to what he sees as an entire history of voids. If Berlin in the early 1990s was famous mostly as a non-space, literally centered on a hole in the ground, Huyssen contends that “the notion of Berlin as a void is more than a metaphor, and not just a transitory condition.”11 He traces the twentieth-century history of the concept, citing Ernst Bloch, who in 1935 described Berlin as a place that “functions in the void,” and touching on the architectural voids left by Hitler’s grand projects, as well as by Allied bombings. Thus, he says:

When the wall came down, Berlin added another chapter to its narrative of voids, a chapter that brought back shadows of the past and spooky revenants. For a couple of years, the very center of Berlin, the threshold between the Eastern and Western parts of the city, was a seventeen-acre wasteland that extended from the Brandenburg Gate down to Potsdamer Platz and Leipziger Platz, a wide stretch of dirt, grass, and remnants of pavement under a big sky that seemed even bigger given the absence of a high-rises skyline that is so characteristic of the city.12

For Berlin, as for Germany, the center that formed the border of East and West is the biggest void of all, and it is this uncanny space between places that Zentropa works to bring to light.

The difficulty of seeing such a non-space is voiced textually, where the void of German space resolves into a relationship between nothing to see and too much to see. The claim that there is nothing to see is first made by Leo’s uncle, when Leo tries to look out the window in the dormitory room in which he is staying. Angrily pulling back the curtains, Herr Kessler accuses Leo of waking those workers on night shifts and tells him that there is, in any case, nothing to see from the window. The phrase recurs on the train, where once again Leo is attempting to look out a window. This time, as the train leaves the platform, he pulls aside the blind and sees a mass of people running alongside the departing train, begging for money. Again his uncle pulls down the blind, claiming angrily that there is nothing to see and asking, “Have you no decency? The blinds must be closed, that is the rule.” The visual consequence of this rule is to prevent the train windows from becoming screens to depict the landscape, and so the space of the train appears to be entirely separate from the country around it. As far as the landscape goes, there may or may not be nothing to see, but there is certainly nothing seen.

Zentropa Nothing to see, or too much to see?

The claim of nothing to see is also made by the hypnotist in voice-over. Addressing Leo during his first journey as a sleeping car attendant, he intones, “You have traveled through the German night … you have met the German girl … but as you go on with your job in car 2306 there is little to see.” The image that accompanies this speech is an extreme close-up of Leo’s eyes at the top of the frame, and superimposed at the bottom is the train itself moving across the screen. As the juxtaposition of this voice-over with the image of huge eyes begins to suggest, however, the repeated claim that there is nothing to see implies an anxiety that the reverse might be true. And Leo does see out the train window in one scene, when Katharina opens the blinds to reveal the horrific sight of two hanged terrorists. If the discourse of “nothing to see” speaks of the fear of what might be seen, then this momentary image of dead bodies confirms that the view from the train is, indeed, too much. These dead bodies, like the starving men glimpsed later on the train, exemplify the European history that is too horrific to be seen, where “too much to see” refers explicitly to a politics of representability. But this notion of excessive vision is not just a political metaphor but a function of spectacle, where the tension between what can and what cannot be seen structures the film’s historicity and enables a complex engagement with the image of the German and European past.

Intertextuality, Postwar Film, and the Ruin Image

We can see a key elaboration of this structure in Zentropa’s intertextual references to another group of films set in immediate postwar Germany. In the wake of occupation, a number of films were shot in the ruins of Berlin and Frankfurt, and, like Zentropa, most of them were not German. In films such as Germany Year Zero, A Foreign Affair, and Berlin Express (Tourneur, 1948), the country was imagined not from a national but from an international perspective. These 1940s films—made, respectively, by an Italian and by expatriate Europeans in the United States—provide some of film history’s most iconic images of post–World War II Germany, and yet they are not products of a German national cinema. In them, the nature and status of Germany become not national truths to be represented but the object of visual inquiry. To refer to these films is to invoke this history, in which the image of Germany becomes a projection by others onto a divided and uncertain space. Zentropa repeats this work of projection by dint of its status as another non-German film representing Germany in 1945, but it also textualizes the repetition through visual and narrative reference.

The narrative similarities are plentiful: from Germany Year Zero, Zentropa takes the fraught process of denazification, a question that also figures prominently in Berlin Express. Both films question the process’s efficacy but nonetheless depict somewhat idealistic characters who are determined to make a difference in the new Germany. A Foreign Affair centers on a romance between an American man and a German woman who may or may not have been a Nazi. Like Max Hartmann in Zentropa, Marlene Dietrich’s character, Erika von Schlütow, has the questionnaire designed to assess past Nazi involvement falsified by an American officer. And like von Schlütow, Katharina Hartmann turns out, indeed, to have had a Nazi past. Also quoted is the German postwar film Murderers Among Us, which, along with the foreign films, narrates the problems of national reconstruction in terms of guilt or innocence. Zentropa takes the noirish cast of its investigation from Murderers Among Us, and it cites, almost shot for shot, a scene in a bombed-out cathedral.

Murderers Among Us Christmas Mass takes place in a bombed-out cathedral, with snow falling on the congregation.

Zentropa The scene in the cathedral echoes that in Murderers Among Us, with a reverse shot of Leo entering the ruined church.

The most extensive structure of intertextuality, though, is that between Zentropa and Berlin Express, which, as its title suggests, is also a film about trains.13 Both films feature an American protagonist in Germany, with Lindley, like Leo, something of an innocent caught up in political intrigue beyond his grasp. Both films center on the dangers of terrorism from remaining Nazi sympathizers. Berlin Express contains an assassination plot against a good German on a train, a narrative device that is echoed directly in Zentropa’s sequence of the assassination of Mayor Ravenstein on Leo’s first overnight assignment. Most strikingly, Berlin Express also uses a second-person narration, in which a disembodied voice-over narrates the American protagonist’s actions as they happen on-screen. Thus, as Lindley walks toward the American military headquarters in Frankfurt, the voice-over says: “You approach the entrance to the U.S. Army base.” This unusual narrative strategy comes closest to that of Zentropa in a scene in which Lindley travels on the titular train. He is looking out the train window, uneasily, as the voice-over says: “You’re in his territory now … you’re still not so sure you’ve got the upper hand … then you find yourself rolling over the former enemy border.” The image is a point-of-view shot out the train window at night, showing a forest and a deserted road. The mysterious quality of the German landscape in relation to the known but perhaps still dangerous space of the train is made explicit when the voice-over comments: “Then back comes the doubt … you’re in his territory now. The trees look the same, the sky’s the same, the air doesn’t smell any different.” Like Leo, Lindley experiences German space by means of the train, and both films question what you can tell by looking out the window and whether the space of Germany is, after all, safe for foreigners.

But if Zentropa reminds us of a history in which German space was imagined from an international perspective, it also opens up a temporal and formal gap between the conditions of visual possibility in 1945 and those in 1991. For what makes the films of Jacques Tourneur, Billy Wilder, and Roberto Rossellini historically significant is not merely their timely narratives but their location shooting. These films were shot among the ruins of German cities, and they show an extremity of destruction that was historically unique.14 A Foreign Affair opens with the American contingent flying into Berlin, and the aerial point-of-view shot from the window of their plane makes visually clear the vast extent of the city’s destruction. Entire streets are missing, and most buildings are empty shells with only a few jagged walls left standing. Later in the film, in a shot construction also used in Germany Year Zero, characters walk or drive through the streets in sequences barely motivated by journeys that would classically be elided. In these narratively excessive tracking shots, the characters in the foreground signify less than the rubble that is constantly behind them. Here it is the documentary force of the ruin image—familiar to the contemporary audience from newsreels—that anchors the films’ claim on the real. Although the films variously involve romantic, political, and mystery narratives, their power to represent the stakes of the postwar German problem comes as an effect of the evidentiary quality of their ruined mise-en-scènes.

A Foreign Affair Ruins are emphasized in the background of shots.

Germany Year Zero Ruins are emphasized in sequences of journeys that would classically be elided.

That this concern for the indexical truth of the ruin image is part of the averred work of the films can be seen in the opening credits of A Foreign Affair and Berlin Express, both of which refer explicitly to their location shooting. A Foreign Affair begins with the intertitle, “A large part of this picture was photographed in Berlin.” This assurance does not enable a better understanding of the narrative, which is largely generic and could have easily been shot in a studio; what it does is authenticate the film’s relationship to Berlin’s impossible space. Even more clearly, Berlin Express opens with the credit, “Actual scenes in Frankfurt and Berlin were photographed by authorization of the United States Army of Occupation, the British Army of Occupation, the Soviet Army of Occupation.” The opening shot—as with all these films—is of rubble, and the title ensures that this space is read not as a set but as an index of the film’s spatial and hence political authenticity.

Of course, the image of the German ruin is not confined to these films, and, indeed, within Germany, in what remained of a national film industry, a genre only half-ironically called the Trümmerfilm (ruin film) grew up. In addition to the well-known Murderers Among Us are films like Marriage in the Shadows (Maetzig, 1947) and Between Yesterday and Tomorrow (Braun, 1947), which use established genres such as the family melodrama and the thriller to address the recent past.15 The relation of these films to discourses of indexicality is complex and can by no means be reduced to a univocal realism. For example, Thomas Elsaesser has emphasized the nonnaturalistic generic forebears of the German films, describing them as “halfway between Weimar’s sordid realism and Hollywood’s film noir.”16 And politically, too, these films run the gamut from critical social engagement to flagrant apologism and self-pity. Nonetheless, what binds these disparate films to one another and to the American and Italian ruin films is not reducible to a coincidence of location but pertains to the Benjaminian aura and to the effect of indexicality that we find in certain spatial images.

As I suggested with regard to Underground, two radically different images stood in the moment of 1945 as guarantees of indexicality and, as a consequence, as fetishistic promises of the visible truth of various postwar nations: the beautiful national landscape and the impossible space of the ruin. In regard to Germany, more than anywhere else, the ruin became in 1945 the key signifier of postwar truths. Germany Year Zero demonstrates the extent to which these spatial tropes are intertwined: in this film, the neorealist logic of the Italian national landscape is replaced with German destroyed space, for these images are two sides of the same coin. As Jousse argues, “Through a process asymptotically approaching documentary, [Rossellini] again delineates a quite concrete territory where the question of real space is determinant (especially in Germany Year Zero).”17 The idea of real space, of the materiality of the postwar nation, became central at the historical moment when the future of many European nations was uncertain, and their physical destruction by war rendered visible a cost in human lives that was less easily representable—hence the ability of certain images of national space to produce an emotional effect of indexicality, wherein these cinematic images could offer to stand both within and beyond realism as the punctual truth of the postwar nation.

But there are no true ruin shots in Zentropa, and this absence as much as any of the intertextual references determines the film’s relationship to the time and space of postwar Germany. The only views of wartime destruction in the film are the few establishing shots of the exterior of the Hartmann residence in Frankfurt, a brief exterior shot of a street, and the scene that echoes Murderers Among Us in a bombed-out cathedral. For example, we see Leo and his uncle arrive at the Hartmann house in long shot, with the house taking up most of the background and some rubble on the street in between. Although the rubble clearly connotes ruined buildings, the house in the background is intact and, indeed, somewhat palatial. The cathedral scene also undercuts its ruin status: while there is logically a ruin, for snow is falling inside the church, the establishing shot of the cathedral’s facade does not reveal this destruction, and once inside it is impossible to see the walls. Editing produces the meaning of a ruined cathedral, but there is no individual image of destruction. In none of these scenes is ruination either clear or foregrounded. Aside from these few and inconclusive shots, the film takes place almost entirely indoors: on trains, inside the train station, in offices, and in the Hartmann house. The few exterior shots that exist either are in the countryside or are so tightly framed that no setting can be discerned.

Of course, there could be no actual ruins in a film made in 1990: unlike Underground, Zentropa was not filmed in a new battleground that could stand in, visually, for a historical one. And as a result of this difference, any ruin shots that might exist in Zentropa could not produce the affective shock of those in the 1940s films, for they would code only as set design rather than as momentary flashes of the real. Nonetheless, given the extent to which the film quotes these earlier ruin films, it is striking that the destroyed urban landscape of its German city settings is virtually absent from the mise-en-scène. Zentropa’s omission of ruin shots—and, indeed, its virtual omission of exterior long shots of any kind—is a structuring absence, a void that works against any mobilization of nation, effectively bracketing the mise-en-scène as a spectacle that refuses authenticity, a cinematic space outside the discourse of place.

This de-realization of space separates German space from the discourse of the nation. Without reference to the image that claims to be an index of postwar Germany, the film’s space becomes both nonnational and unreal. But the absence of the ruin image is more than a refusal to represent a concrete national space: it is also a refusal of the ideological implications of the postwar German ruin. For if the Italian films used the indexical landscape image as part of a leftist claim on the new republic, the films set in Germany took the ruin as a liberal, rather than a radical, signifier of political redemption. In the conflation of liberation with ruination, images of rubble became signifiers of a cleansing of Germany, in which the Third Reich was physically swept away and the pain of destruction formed a catharsis for the German people. The ruin spoke as the fresh start made material. Thus, Michel Celemenski can argue that “at degree zero, humanity cannot but find its redemption. This is the principal message of Tourneur, Staudte, and Rossellini.”18 Here, the real landscape has a redemptive power that the narratives of the films, to a greater or lesser degree, can endorse.

But although the idea of the year zero caught on in public discourse, it holds little water as a serious political category. Elsaesser asks pointedly: “Was May 1945 the famous ‘Zero Hour’ and the chance for a new beginning or, rather, already the return of a period of political restoration, the creeping and scarcely clandestine rehabilitation of former Nazis in positions of power: industry at first, then government, administration, the judiciary, press and education?”19 Clearly, he thinks the latter, and this interpretation of the postwar years is the dominant one in contemporary historiography.20 And if the concept of a year zero is problematic, then so, too, is the ruin film, which became its visual correlative. The ruin image proposes a fictional break, which preempts any need to engage with the recent past. It enables the reassuring idea that Nazism is firmly consigned to the past, producing a discourse of new beginnings, at once optimistic and self-indulgent. For any claim on German national subjectivity, it is a sign of guilt and a sign of penance. It implies a new “we”—the we who regret—and this new subject cancels out the old Nazi one, articulating a non-Nazi German subject that precludes any possibility of Nazis remaining in the rubble. Thus the notion of a redemptive year zero can be seen as papering over the recent past.

The humanistic use of the ruin as redemption is put under scrutiny by Elsaesser with regard to the German-made films. Far from enabling a liberal politics of reconstruction, he suspects, the narratives of “middle-of-the-road protagonists, ordinary people, caught up and implicated through cowardice and misguidedness … offered a [German] audience prepared to be contrite the comfort of fatalism and self-pity.”21 While he does credit such films as Murderers Among Us with critical social engagement, he is also suspicious both of that film’s noirish mise-en-scène and of the various attempts at a neorealist engagement with everyday life among the ruins. He argues: “Thus the thriller format made it seem as if Nazism had been a conspiracy perpetrated by a clique of fanatics, lunatics and underworld criminals. The neo-realist mode, however, was always in danger of becoming frankly apologetic, suggesting that moral decency and individual courage had prevailed throughout and that the war when it came was the universal human tragedy it has always been in the popular mind, like a natural disaster such as a flood or a drought.”22 Naturally, these two impulses are not identical, and I do not want to conflate the politics of the postwar German film industry with the texts of Rossellini and Tourneur. But across their variously debated ideological imperatives, these films all share a logic of trauma in which the image of the ruined city promises both access to the real and a more or less overt stake in a liberal definition of that reality. The disruptive trauma of the real, along with the bombing of Germany, is defined as happening before the “now” of the indexical image. By locating the horror of German space in the image of the ruined city, the ruin film places the dislocation of Nazism firmly in the past and offers the need for reconstruction as a visual correlative of the political need to look forward and begin anew.

In omitting the ruin image, then, Zentropa refuses this logic and, with it, the liberal discourse on German identity and postwar history. If the year zero is a lie, the film refuses the contemporary image of that lie and, in so doing, suggests a different articulation of postwar history. The film’s narrative directly thematizes a rejection of year zero optimism, both generally in the idealistic Leo’s failure to help Germany and specifically in the focus on Nazi sympathizers from the Werewolves to the Hartmann family. The logic of the German ruin is one of temporal breaks, wherein the past is fundamentally distinct. It is the time before ruins. The future, equally, is distinguished as the time after ruins, when reconstruction will enable a new beginning predicated on complete change. Although this logic considers loss, basically it works to separate the present from both past and future, presenting Germany in 1945 as a blank slate. By contrast, Zentropa’s refusal to use the ruin image means that it can neither engage a rhetoric of a separate before nor look forward to a different future. Like Underground in this respect, the time that would seem to form a before is actually already in the history it seems to precede. For Germany, as for Yugoslavia, the end of the war is not a simple break. The supposed year zero was a fake, and in 1945 there was both still the legacy of Nazism, which has not disappeared, and already the divisiveness, zoning, and international expedience that would form the basis of the Cold War.

In its intertextual construction, then, Zentropa performs a doubled movement: on the one hand, it refers to the films of the immediate postwar years in Germany, but, on the other, it works to remove those textual elements that function as signs of a material space and time. As a result, place becomes unsettled, with German space being overlaid with the uncanny space of “Europa.” But this troubling of the cinematic year zero discourse is not only spatial but temporal. It is temporal first in that by refusing the year zero concept, the film also refuses to locate Germany in a historical limbo. Instead, time spreads outward, bleeding back into Nazism and forward into the Cold War. But the ideological weight of these references is also historically contingent. To cite the aftermath of World War II takes on new meanings also in the wake of German reunification, when the relationship of Germany to Europe and the history of war and Cold War became once again politically central. It is in this context that Zentropa was released, and it is therefore necessary to read the stakes of its history through the politics of its present. We return once more to the question of 1945 from the perspective of 1991.

The historical moment of Zentropa’s release was much on the minds of its critics: as with Underground, current events conspired to ensure that the film was easily read as topical. Zentropa was released in Europe in 1991, just over a year after the reunification of Germany and less than two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. And although the film is set entirely in the past, with none of the narrative codas that tie Cinema Paradiso’s and Mediterraneo’s historical situations to the present day, many critics saw the film as a direct commentary on post-Wall Europe. Cahiers du Cinéma read the film as a metaphor, in which postwar fascism and colonization of Europe by America made points about the same forces at work in the 1990s. And Jousse makes the case that “this country in ruins, plunged into a dark night … in a tunnel we can’t see the end of … makes us think irresistibly of Eastern Europe (or Central Europe) today. The same confusion of values, the same sense of nihilism, the same chaos, the same hegemonic force of capitalism.”23

That critical response to Zentropa should have focused on this metaphoric substitution of present for past is not surprising. While Underground makes plain its spatial tropes (the underground tunnel or the broken landscape), Zentropa makes plain a work of historical projection: from postwar to post-Wall. But while most critics saw this projection as a straightforward replacement, I would argue that the two historical spaces must be read together, with this temporal layering producing as much disjuncture as comparison. Just as the space of “Europa” and the space of “Germany” prove irreconcilable in the gap between voice-over and diegesis, so the relationship of past and present is one of proximity rather than substitution. Rather than pursue a metaphoric reading, in which 1945 is a veil covering over the truth of 1991, I suggest a metonymic relation in which the spaces of Germany and Europe, 1945 and 1991, must be seen as contiguous and mutually determining.

For Lars von Trier, Germany is what haunts Europe, exceeding its borders to stand for the continent. In Zentropa, German space can become European space because it is dematerialized and denationalized. Refracted through the lens of 1945 film references, and shorn of the indexical images of the ruined city, “Germany” is conjured not as a national landscape but as a haunting presence for postwar European history. The claim that Zentropa is a film of reunification is correct to the extent that its historical space does imply the unseen space of its contemporary location. The confusing landscapes through which Zentropa’s trains carry Leo are not identical to those of the post-unification nation, but its denationalized space echoes the geography of 1990, in which both Germany and Europe became once again contested concepts. The two spaces are overlaid, without ever touching, like a ghost image on doubly exposed film. In order to map Zentropa’s disjunctive logic of European space and time, we must follow the appearances of this ghost and interrogate just how the film frames European space as horrific.

Dark Continents

Of course, it is not hard to imagine Germany in 1945 as a place of horror. In addition to the vast material destruction documented by the ruin films, postwar German space resonated both with the recent atrocities of the Nazi regime and with the social and political turmoil that came with reconstruction. Widespread displacement and homelessness, a rise in looting and violent crime, and the possibility of violence from Allied soldiers and Nazi terrorists alike produced an atmosphere of, if not horror, certainly uncertainty and menace. And while the zoning of Germany by the Allied occupying forces enabled the construction of new government and social structures, these changes coincided both with the wider shift to a Cold War relationship among the Allies themselves and with the intensely controversial processes of denazification and reeducation of the German populace.24 The remapping of German space that took place as the four zones gradually morphed into two states also entailed a remapping of German national identity, a question that was, after reunification, once more in process.

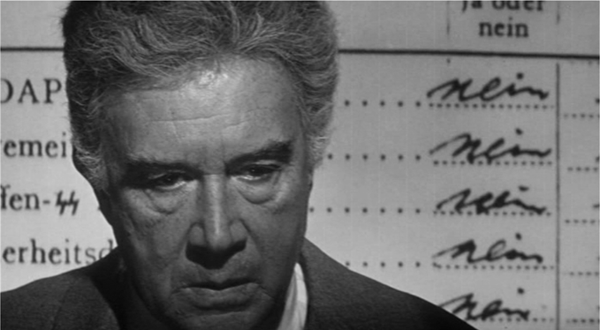

Zentropa’s narrative deals quite directly with a number of these historical issues, most centrally the problems surrounding the denazification questionnaires. Politics is not relegated to the margins of the narrative, as in the Italian films but, as in Underground, forms a major part of the plot. Max Hartmann’s problem is the tension between his high-level links to the Nazis and the economic desire of the American authorities to see that his rail company remains in business. The questionnaire that Colonel Harris delivers to him becomes a dramatic turning point in the scene in which Max is obliged to agree that he saved a Jew. In this scene, the corruption of the process is precisely the point, as the Jew—who has clearly never met Max before in his life—unhappily performs a charade of recognition in front of the American soldiers who have blackmailed him into appearing. In one shot, a close-up of Max has a background of windows that dissolves into a back projection of the questionnaire itself. The document, whose briefly legible lines deny membership in the Nazi Party or paramilitary organizations, fills the frame in extreme close-up, its disproportion emphasizing its narrative significance. In the following sequence, Max is overwhelmed by his lies and commits suicide.

As with the Italian melodramas, however, the substance of Zentropa’s political engagement is not located in such overt narrative references. Rather, politics is again subject to a work of projection, in which generic codes structure the visual and narrative possibilities of the historical look back. The form of Zentropa’s look back is conditioned by the nature of its dark history: since mourning is not the obvious reaction to the German year zero, then it is clear that melodrama will not be the mode in which the period is reimagined.25 Instead, the film appears to evoke dark genres such as the thriller, film noir, and horror. The space of Germany is shadowy and menacing, and in it lurk Nazi guerrillas called Werewolves, a reminder of primitive fears of supernatural beasts. That Nazism should be represented in terms of such a pre-modern discourse of terror might seem simplistic, but this space is repeatedly located in voice-over as “Europa.” It is not that fascism is primitive but that Europe itself must rethink its claim on civilization.

Zentropa A denazification questionnaire is projected behind Max Hartmann.

In this construction of a horrific and nightmarish space, Zentropa takes up a philosophical rhetoric that reverses claims to European civilization and presents the continent’s history of imperialism and genocide as the true locus of “primitive” barbarism.26 Historian Mark Mazower elaborates this position in his book Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century, in which he argues that Europe, not Africa, should be given the epithet “dark continent.” For Mazower, Nazism is not an aberration but the defining ideology of the twentieth century in Europe. Moreover, Mazower sees Nazism’s policy of spatial expansion as primary rather than simply practical: it took the logic of imperialism but transferred its North/South structure into an East/West one in which eastern Europe replaced the primitive colonies. Thus, Nazism brings the imperial dark continent to Europe and, in so doing, inadvertently reveals the true nature of European barbarism. Like Mazower, Zentropa reverses the terms of primitivist discourse, invoking the binary of civilization versus primitivism in order to question the place of Europe in this structure.

Within the field of film theory, the phrase “dark continent” is probably more familiar in the context of its use by Freud to refer to women than in its original, geographic meaning. In her article “Dark Continents: Epistemologies of Racial and Sexual Difference in Psychoanalysis and the Cinema,” Mary Ann Doane points out that “Freud’s use of the term ‘dark continent’ to signify female sexuality is a recurrent theme in feminist theory.” And, she continues, not only do many feminists forget that the phrase is a Victorian one about Africa, but “in its textual travels from the colonialist image of Africa to Freud’s description of female sexuality as enigma to feminist theorists’ critique of psychoanalysis … the phrase has been largely stripped of its historicity.”27 Doane’s article mostly considers the role of the white woman in articulating race and sexuality in American cinema, a topic that might seem distant to the historical questions posed by Zentropa.

And yet both Mazower and feminist theory share a desire to debunk an ideologically problematic attribution of “darkness,” and Mazower’s usage shares with Doane’s rereading of feminist theory a concern for historicity. Freud’s use of the term is metaphoric—the woman is like Africa in her unknowability, her mystery, her need to be mapped by man—whereas Mazower’s dark continent is a literal attempt to rewrite the history of Europe so that it becomes the object of its own description. He is, as it were, returning the gaze. Zentropa also reverses the terms of civilization and primitivism, so that the space of Europe is dark, mysterious, and dangerous. As with Mazower—and, indeed, with Underground’s mobilization of Balkanism—this reinscription of primitivism in relation to European history brings into question the discourse’s structuring assumptions. But in Zentropa, the trope of European space as horrific operates less through a realist representation or narrative engagement with the politics of the war than through a projection of those political questions onto two generic paradigms in which darkness, mystery, and violence are visually and narratively central: film noir and horror.

While Mazower’s use of the dark continent trope is underwritten by a reappropriation of its historicity, he is not concerned with the subject of gender. But film noir and horror frequently center on issues of gender and sexuality and, indeed, have been key areas of analysis for exactly the kinds of feminist psychoanalytic theory with which Doane is engaged. The figures of the femme fatale and the feminized/sexualized monster have been widely theorized by feminists as laying bare the workings of a patriarchal visual economy, and Laura Mulvey’s model of bodily display and narrative investigation corresponds neatly to the colonialist/Freudian metaphor of mapping the mysterious space of Africa/woman. Certainly for Doane, the relevance of Freud’s comparison for feminist film theory is the way it clarifies, inadvertently, the interdependence of notions of the feminine and the primitive, particularly in cinema, where the image of the white woman takes on a crucial role in articulating a racial and gendered ideology of desire.28

The femme fatale, standing for the dangers of femininity yet visually coded in terms of her whiteness (albeit sometimes a pale-skinned, dark-featured type), provides an example of how Doane’s argument complicates previous feminist psychoanalytic theory. But Zentropa forces yet another turn of the screw, explicitly returning the mysterious femme fatale to the history of European expansion and racial politics. Katharina’s uncertain morality derives from her potential connection to Nazism and its policy of, in Mazower’s words, “treating Europeans as Africans.”29 The racial and ethnic politics of Europe in the 1940s underlie, and not only thematically, the mise-en-scène of the 1940s film noir. In Zentropa, the question of genre subtends both a spatial logic (here the dark continent instead of the political landscape) and a gendered one. The discourse of mysterious and primitive space, which encodes an ethnic and geopolitical logic of Europe, cannot be fully exhausted by the spaces of a spectacular mise-en-scène but must be diverted through the body of the woman. Within the intricate layering of these ideological and historical figures, the femme fatale forms a vector through which the logics of primitivism, historicity, and the dangerous space of Europe can be mapped in cinematic terms. By projecting politics onto film noir and horror, Zentropa forms a locus for all these meanings, connecting a critique of the European history of primitivism with a psychoanalytic and cinematic reinscription of the gendered questions of seeing and knowing, desire and memory.

Noir and Fatality

Of course, in analyzing Zentropa in terms of horror and, especially, of film noir, it is necessary to recall that the film is not, really, either. Zentropa must be considered in the context of the contemporary art film rather than as a genre film per se. But it is one of the qualities of the postclassical art film to refer extensively to popular genres: as Amina Danton has argued, while the art cinema of the 1960s often transformed genre conventions, contemporary art films use them directly.30 In addition to the issue of art-cinematic intertextuality, we must consider the generic specificity of film noir. Whereas the Italian films are melodramas, Zentropa is not a film noir but a set of references to noir. Noir, unlike melodrama, is generally thought of as historically and nationally specific. Certainly, there are arguments for various national noirs (for example, in the United Kingdom, France, and Denmark),31 and it has become commonplace to speak of “neo-noirs,” such as The Usual Suspects (Singer, 1995) and The Last Seduction (Dahl, 1994). But there is no need to invent terms such as “neo-comedy” and “neo-melodrama,” and we do not have to make arguments for most genres existing in different countries. Noir is by definition American and postwar, and thus for a contemporary film to be considered noir is inevitably a question of reference. Through this doubling, this distance from the genre’s original status, Zentropa invokes the historical and spectacular codes of film noir.

Zentropa’s most evident reference to film noir is its use of black-and-white cinematography. While some of the film is in color, or colorized, it is mostly shot on a shiny black-and-white stock that implies classical cinema in general and film noir in particular. In the opening scene, for example, Leo stands in a railway yard in the rain. Here, the mise-en-scène adds to the black-and-white film to produce a typically noirish effect: low-key lighting emphasizes dark shadows, with areas of bright light where the rain reflects on the bricks. In addition, other aspects of the mise-en-scène refer to noir conventions (or, indeed, clichés). Leo is wearing a raincoat and fedora, smoke is rising from the building, and he stands in a seedy urban milieu. The only dissonant element is the graffiti on the wall that he begins by facing, which gradually becomes legible as written in German. Within the first scene, the mise-en-scène of American films is recapitulated and then shifted into a European context.

Zentropa’s reiteration of film noir conventions is not limited to the mise-en-scène. The politics of postwar Germany also resonates with the noir narrative of mystery, crime, and moral uncertainty. As Janey Place describes it: “The dominant world view expressed in film noir is paranoid, claustrophobic, hopeless, doomed, predetermined by the past, without clear moral or personal identity. Man has been inexplicably uprooted from those values, beliefs and endeavours that offer him meaning and stability, and in the almost exclusively urban landscape of film noir (in pointed contrast to the pastoral, idealised, remembered past) he is struggling for a foothold in a maze of right and wrong.”32 Almost all these paradigmatic noir elements can be found in Zentropa: Leo is the center of a paranoid structure in which he is observed by everyone, from the terrorists to the American colonel and the railway company adjudicators, and the mise-en-scène of the trains is highly claustrophobic. Leo is a hero uprooted from his stable life as a conscientious objector in the United States and thrown into the amoral and dangerous universe of Germany in 1945. And the setting is indeed mostly urban, for the impossibility of landscape returns as a defining feature of Zentropa. The distance of Zentropa’s version of Europe in 1945 from that of the Italian films can be described as the distance from the political landscape to the impossible space or from the 1945 of neorealism to that of film noir.

The relationship of present to past is also, as Place makes clear, one of the key narrative tropes of noir. Pam Cook takes up this discussion in her reading of Mildred Pierce (Curtiz, 1945), in which she argues that noir as a genre works on the historical anxieties of the postwar period. For her (and for much feminist work on the genre), noir expresses both the repression of women and the reestablishment of a failing patriarchy after the war, where “this re-construction work … rests uneasily on this repression, aware of the continual possibility of the eruption into the present of the submerged past.”33 Place’s version of the lost idyllic past—represented, for example, in Out of the Past (Tourneur, 1947)—is not taken up directly by Zentropa, where there is no image of a time before the chaos and mystery of the narrative present. Neither does Zentropa’s version of the postwar situation so easily fit Cook’s gendered reading, which is, of course, specific to American films and politics. But the notion of a barely repressed past that might at any moment erupt into the present is uniquely relevant to the notion of postwar Germany as dark continent. The idea of a past crime that haunts the present is quite obviously political in Zentropa’s Germany and only shallowly submerged.

Of course, film noir already has a European past: while the genre is by definition American, its roots in interwar Europe are well known. Its aesthetic forebears include German Expressionism and French poetic realism. Even more important in this context is the mode of transmission of these influences to Hollywood, largely in the shape of European filmmakers (including actors, cinematographers, and other technical crew, as well as directors) who emigrated to the United States to escape from Nazism. Directors such as Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder helped influence American film of the 1940s, and thus we can read film noir, even at an industrial level, as a palimpsest of the history of Nazism. While only a few noir films refer directly to Nazism (for instance, the British noir The Third Man), the bad past is central to the historical evolution of the genre.

But Zentropa includes the investigation of an explicitly wartime past: Leo must discover whether Katharina was a Werewolf, if her father was a Nazi, and what was the history of the Zentropa railway company. The weighty question of what happened in the German past appears at various points in the narrative, most obviously in the scene with the Jew who tells the lie that Max Hartmann saved him. This sequence opens up the past in terms of German guilt or innocence and, of course, implies that the past is being falsified and covered up. Not only is there a bad past in noir, but the present does not always bring truth to light. There is also a sequence of emaciated Jewish prisoners on the train, which forms a brief visual trace of the railway’s past of transportation. (The figure of the Jew appears in Zentropa only in terms of what cannot be seen within the text. Either it is the unrepresented past—where the first Jew narrates a false past to cover over the implied real one, and the Jews on the train appear as hallucinations from a past that the film cannot represent—or it is the extratextual future, for the Jew who exonerates Hartmann is played by Lars von Trier, in a cameo role that reminds the spectator of the present-day origins of the film.) In both cases, the difficulty of excavating the German past underwrites the noir investigation.34

Moreover, Zentropa adds another level of temporality to the noir relationship to the past, for Leo’s experiences in postwar Germany are themselves the subject of a historical excavation. The noir plot is framed by a narrative structure of hypnosis, in which the entire diegesis is supposedly being remembered by Leo as an analysand at some time in the future. The film opens with a shot of railway tracks in the dark, and as the camera penetrates farther into this almost abstracted space, the voice-over intones “you go deeper and deeper and deeper.” Falling into the psychic depth of a hypnotic trance is figured visually as moving forward into space, and this depth of field thematically sets up the dark, mysterious space of Europe as the landscape traversed by the German train. The voice-over continues, “on the count of ten you will be in Europa,” placing European space as the end point of an unknown etiology and suggesting psychoanalysis as the mechanism for investigating the traumatic past. Shifting noir conventions slightly, the voice-over comes not from the protagonist but from his apparently omniscient analyst. Read in these terms, the entire narrative is an attempt to bring the past to light, a psychoanalytic return to the scene of the crime.35

It is telling that the form in which the present exists within the film is so marginal. We never see the present: it is entirely absent from the image track and heard only at the edges of the soundtrack. The hypnotist’s voice is the only trace of the present within the text, and his second-person monologue serves to emphasize the empty or invisible space of the present-day European subject. We can see Leo, the conjuration of hypnotic suggestion, who dies in 1945, but what remains unseen is the subject who looks back. Equally, we can see the Europa of 1945, with its noirish mise-en-scène and its primitive and horrific spaces, but there is no image of the Europe of the present from which this historical space is projected. The horrific nature of this past inheres for the spectator, much as it does for the hypnotized Leo, in the fact that there is no outside to it. The hypnotic voice-over is a framing device, but there is no access to the frame. It exists only to demand a position of knowledge, to locate the spectator as a subject who looks back to the historical moment of the narrative, but it does not allow the present to rescue either spectator or protagonist from the exigencies of the past.

Thus, Zentropa takes up the temporality of noir to figure the impossibility of a certain kind of historical narrative: the past does not necessarily shed light on the present. If the Italian films offer the experience of mourning, and Underground the uncertainty of melancholia, Zentropa textualizes the failure of psychoanalytic mechanisms to excavate the past. As Leo overcathects to the past, he loses the present, dying inside his hypnosis. The narrative of psychoanalysis promises to uncover the root of neurosis, just as the film noir promises to reveal the truth of past crimes. In each case, there must be an originary scene that will, as in Pascal Bonitzer’s theory of the filmic labyrinth,36 explain all that has come before in the narrative and all that comes after temporally. But, like many film noirs, Zentropa provides no primal scene at the center of its labyrinth: all that Leo’s analytic inquiry leads to is death, and the film’s investigative structure disappears into a void. Within the historical narrative, Leo is unable to help Germany or Katharina and is instead killed by the forces competing for Germany’s future. In the framing narrative, there is even less resolution, for Leo’s death inside his hypnosis illogically precludes any return to the narrative present. In either case, the look back is neither nostalgic nor melancholic, but fatal.

And the concept of fatality leads us inexorably to the figure who is, in 1940s films noir, the locus of moral uncertainty and possible past crimes: the femme fatale. Place’s description of “man” as the subject uprooted from his moral values and stability is deliberate, for noir films conventionally center on the tension between a simple, upright male protagonist and a dangerous urban landscape, which is, quite directly, personified in the morally dubious but sexually alluring woman. Katharina is coded as a femme fatale first by her appearance: she dresses in glamorous 1940s fashions and is frequently framed in close-up. In the scene where Leo meets her for the first time in her father’s private train compartment, she is initially seen in a full-color close-up, while the surrounding shots—including a reverse shot of Leo—are in black and white. This emphasis on her image as spectacular goes hand in hand with a conventional noir narrative of ambiguous morality. In the train scene, Katharina explains to Leo the existence of the so-called Werewolves: Nazi guerrillas who are being executed by the Allies. Later in the narrative, Leo has fallen in love with Katharina, and as she undresses, she confesses that she used to be a Werewolf. As she makes this confession, Katharina is framed in a moment of classical to-be-looked-at-ness, lying down and wearing a sheer slip, her hair fanned behind her. The femme fatale as erotic spectacle and as narrative threat are momentarily identical.

Zentropa The femme fatale is framed as an erotic spectacle of bodily display.

Where Zentropa alters, or rather augments, the traditional noir narrative is in the overt and self-conscious emergence of history into this scenario. While film noir has been theorized as a reaction to the politics of postwar America, Zentropa textualizes this process, making the recent history of the continent central to the plot. Thus, the dangerous urban landscape that Katharina personifies is not merely criminal but specifically Nazi. Elizabeth Cowie describes noir in terms of “a masculine scenario, that is, the film noir hero is a man struggling with other men, who suffers alienation and despair, and is lured by fatal and deceptive women.”37 Here, the men with whom Leo struggles are the mysterious forces of Nazism, who do not form an individual threat as much as a constantly unknowable and alienating landscape. Marc Vernet has mapped this relationship spatially, arguing that “the ‘triangle’ has often been pointed out as a principal form of relation among the characters: the young hero desires and conquers a rich woman who is quite often tied to an older man or some other representative of patriarchal authority.”38 In Zentropa, Nazism forms the third point of the triangle, to which Katharina is tied through the figure of her father. As the owner of the Nazi-era rail company Zentropa, as well as Leo’s father-in-law, Max Hartmann represents patriarchal authority as inescapably linked to the Nazi past.

According to Doane, the femme fatale represents, above all, a problem of knowledge: “She harbors a threat which is not entirely legible.”39 And it is this mystery that the film noir narrative works to uncover. Her illegibility goes hand in hand with her spectacularity, so the question of knowledge is tied to vision. Excessively visible and yet narratively ambiguous, the femme fatale disturbs the relationship between what can be seen and what can be known. Katharina centers the question of what we can see of Nazism: the spectator cannot be sure if she is still a Were-wolf, and the narrative works to close up this disjuncture between sight and knowledge. But this problem of knowledge—that we cannot tell who is guilty just by looking—not only is the case with regard to Katharina but describes the key problematic of Zentropa’s postwar German landscape. The space of Zentropa’s narrative is determined by this “epistemological trauma,” where, as in Berlin Express, Leo’s point of view is based on doubt about the status of the landscape around him. (“Then back comes the doubt … you’re in his territory now. The trees look the same, the sky’s the same, the air doesn’t smell any different.”) This is where the femme fatale focuses the political logic of the dark continent, defining European space as that which is dangerous, uncertain, and, most of all, duplicitous.

Werewolves, Cats, and Women

“Duplicity” is a defining term of the femme fatale, but Katharina’s duplicity is not limited to this generic figure. The narrative source of her guilt is her membership in a Nazi terrorist group, the Werewolves, and the idea of the werewolf also connects Zentropa to the horror genre. The doubled body of the werewolf is another figure of duplicity, seemingly human by day, but transforming into a monstrous creature by night. Of course, Katharina is not literally a werewolf, unlike the protagonists of classical “monster films” such as The Wolf Man (Waggner, 1941), supernatural beings who morph from human to wolf. Her change is not physical but ideological, from the “good German” during the day to the Nazi terrorist by night. This day/night logic is underscored when Katharina tells Leo how she worked with her father by day and then at night wrote the threatening letters that he received from the Werewolves. But the generic conventions of the werewolf (and of the hybrid human-animal in general) nonetheless underpin Zentropa’s construction of the dark continent and the discursive place of the woman within it.40

The first characteristic of the werewolf, as of the femme fatale, is a question of visibility. Because he or she seems human during the day, we cannot be sure who is a werewolf. In a generic horror film, this uncertainty becomes the site of suspense—either about the existence of a monster or about the time and place it might strike.41 In Bonitzer’s terms, the werewolf exists in blind space: the off-screen space that produces suspense. The monster, like the femme fatale, is a spectacular object, but its spectacularity depends on its being invisible for most of the horror film. In Zentropa, the invisibility of the monster is figured in terms of the thriller narrative, where the terrorist Werewolves operate clandestinely and are rarely seen. Moreover, when they are seen, they are hard to see as werewolves, for their bodily duplicity means they look just like everyone else. Thus, on two occasions, werewolves are labeled in writing to ensure visibility. The first example comes when Kate raises the blind and looks out the train window, only to see the bodies of two hanged men, with signs around their necks reading “werewolf” in German and Russian. Here, the writing serves narratively as a sign of guilt, but it also initiates a structure whereby the werewolf’s body is deceptive and must be made to speak visually.

This structure repeats later in a train sequence, when Leo is sitting alone in the train corridor. He is in the lower-left-hand corner of the frame, and projected behind him is the word Werwolf in disproportionately large letters. At this point, the image works mainly to reinforce the idea of the werewolf being visible only through the written word, where the identities of the terrorists are mysterious and their plans unknown. Much later in the film, however, Leo is once again on the same train, on his honeymoon with Katharina. Again, he sits alone and is framed in the corner of the screen, and once more a giant image is projected behind him, representing his thoughts and anxieties. This time, the image is of Katharina’s face. The effect is unusual, and its repetition inevitably recalls its previous use, so that Leo’s projected image of Katharina is itself superimposed, for the spectator, onto the earlier image of the word Werwolf. This doubt about Katharina’s status follows the moral ambiguity of the femme fatale: while she is repeatedly connected to the Werewolves—in mise-en-scène, as here, and in narrative—she is never seen to be one, and the spectator can therefore never be entirely sure of her guilt.

The second defining term of the werewolf proceeds also from its doubled body: the binary of day and night, human and animal, entails a logic of civilization and the primitive. In the horror film, it is frequently a modern, scientific milieu that is threatened by the supernatural, inexplicable, and animalistic. And the werewolf, with its human and animal elements, is able to trope a specifically modern fear of the primitive lurking within civilization. Thus, Walter Benjamin, writing about Poe’s “Man of the Crowd,” describes the story as “the case in which the flâneur completely distances himself from the type of the philosophical promenader, and takes on the features of the werewolf restlessly roaming a social wilderness.”42 Here, the werewolf represents the frightening aspect of modern life, which includes the possibility of evil existing within the city crowd, precisely because the city is also a wilderness. Modern space is also primitive space in the werewolf metaphor: the modern man may also be a beast, and the problem is that you cannot see the difference. Thus, by presenting postwar Germany in terms of hidden werewolves, Zentropa works on both the overt iconography of the horror genre and its historical underpinnings. Europe becomes a primitive place where beneath the veneer of civilization lies the dark continent.

There is one notable difference between Katharina and the conventional horror film werewolf, however, and that difference is gender. As a femme fatale, Katharina is structured as a gendered spectacle, but the werewolf figure in most horror films is male and rarely seen as a site of sexual threat. The threat of the werewolf is primitive violence, but the primitivism is that of excessive masculinity, viewed as unrefined by the morality of civilized society. The beastliness of the werewolf contrasts in this respect with the feminization of many other horror film monsters, such as the vampire and the alien. However, Zentropa’s shape-shifting femme fatale does have a cinematic predecessor: the protagonist of Cat People (Tourneur, 1942), who may turn into a more conventionally feminine feline monster. Cat People, I think, functions as another art-cinematic intertext for Zentropa,43 but, more important, its interconnection of the femme fatale and the monster subtends a discourse of primitivism that enables a clearer analysis of exactly how these generic figures produce, in Zentropa, a somewhat different historical and spatial system.

Cat People ties monstrosity quite explicitly to both female sexuality and a dark European history. Irena is a Serbian woman who believes that is she is under an ancient village curse, whereby she will turn into a panther if she is sexually aroused and attack her partner. Her all-American husband rejects this belief as mere superstition, but he is finally attacked by Irena, who kills herself in remorse. The film has been analyzed frequently, mainly in terms of its sexual logics (although not always from a feminist or psychoanalytic perspective), with Irena’s excessive and animalistic sexuality forming the central term of debate.44 Doane’s reading ties a feminist reading to a historical one, pointing out that “this opposition [between rational and irrational, science and poetry] is mapped onto what in 1942 was necessarily another heavily loaded opposition—that between the native and the foreign, the ‘good old Americano’ and the Serbian, the familiar (Alice) and the strange (Irena).”45

This nexus of terms is part of a wider analysis, and Doane’s interest in Irena’s national identity is only that “Serbian” connotes a general sense of sinister exoticism. In the context of my argument, though, it becomes telling that, in World War II, Serbia was on the American side and not, therefore, an obvious historical choice for demonization.46 A wartime suspicion of the foreign undoubtedly plays a role in the narrative’s general opposition of American to exotic, but the specificity of Irena’s Serb background returns to a familiar structure. Serbia, as I argued in the previous chapter, signifies as primitive and exotic within the twentieth-century Western discourse of Balkanism, the same logic of abjection that Underground works on. And so Cat People, too, places its fatal woman within the logic of the dark continent. None of the readings of the film take up this ideological structure of primitivism, other than implicitly in the chain of associations—woman/irrational/primitive/sexual—that operates in the various feminist analyses. As with the trope of the dark continent in feminist theory, the primitive and exotic space is a secondary marker of the strangeness of female sexuality. That Irena is Serbian functions analytically as a symptom of her excessive sexuality, even though narratively it is presented as a cause.47

Cat People Framing, costume, and mise-en-scène associate Irena with the animalistic, the dark, and the exotic.

But in Zentropa, the elements of this structure are reversed, and the sexuality of the monster/femme fatale is no longer primary but symptomatic of the primitive nature of postwar European space. The political duplicity of 1940s Europe, which is unable to be expressed fully in the historical narrative, recurs in the mise-en-scène of film noir and horror, and, as with the Italian melodramas, the body of the woman is the site of this projection. Katharina, like Irena, is figured as both femme fatale and monster, although her duplicity does not imply an excess of female sexuality; rather, like that of the romantic objects in Il Postino and Mediterraneo, her duplicity operates as a fetish, standing in for what cannot be seen. And what cannot be seen, in Zentropa, is the impossible space of the continent: the barely submerged history papered over with a discourse of civilization and a western definition of “Europe.” As politics is displaced onto romance in the Italian films, here it is displaced onto the amour fou of the fatal woman, which stands in not for the optimism of the young nation but for the seduction of the dark continent.

Gender is the discursive space in which this historical logic becomes visible. The figure of the dark and mysterious woman is a placeholder for political and historical traumas that are textually unspeakable. And this is exactly Doane’s argument about the cinematic dark continent, where the white woman figures the unspeakable difference of race. In Cat People, we have the Serbian woman, in whom Balkanism returns in a gendered economy in which primitivism and darkness operate not in the usual Balkanist discourse of masculinity and savagery, but hitched to the Hollywood visual economy of excessive female sexuality and the visible/invisible monster of the horror film. These disparate versions of otherness have a cinematic history of interconnection: the foreign, the un-European, the feminine, the primitive, the sexual, the thing that you cannot quite see or cannot quite know, the epistemological problem of the femme fatale. What changes in Zentropa is that Katharina is not locatable as un-European. She is German and, in terms of the film’s geographic slippage, stands as an exemplar of Europe as a whole. Germany in 1945 is, for Zentropa, the center of and not the exception to the continent’s dark history. Thus, the space of excessive femininity and geographic abjection moves west and north, becomes “whiter.” In Underground, the space of Yugoslavia is abjected, precisely unable to be located within Europe. In Zentropa, the excessive part is not only in Europe but also at its center. It is too European. And in locating an excess not within Europe but of Europe, the film begins to reimagine the continent’s visual geographies.