3 A Conspiracy of Cartographers?

For Tom Stoppard’s paranoid Rosencrantz (Rosencrantz and Guilderstern Are Dead [Stoppard, 1990]), space is purely a matter of representation and, in true postmodern style, he has lost faith in the authority of the map:

Guildenstern: What a shambles! We’re just not getting anywhere.

Rosencrantz: Not even England. I don’t believe in it anyway.

Guildenstern: What?

Rosencrantz: England.

Guildenstern: Just a conspiracy of cartographers, you mean?

As the cannier Guildenstern’s sarcastic comment implies, however, we cannot read cartography simply as conspiracy. The existence of England, after all, is not in doubt. What is at stake is the production of cartographic authority: who draws the maps, and what relationship is articulated between image and reality. This question emerges forcibly in Europe in 1989, when events began to produce new territories and indeed new mapmakers. Less publicly, though, 1989 also saw the beginnings of a new critical challenge to cartographic authority. In this year, the geographer J.B. Harley published “Deconstructing the Map,” an article that, in reading maps in relation to poststructuralist theories of textuality and power, essentially initiated the area of critical cartography.1 The coincidence of these dates is felicitous, suggesting a historical linkage of political and intellectual change; the breakdown of the Cold War geopolitical order not only entails the well-known crisis of Marxism but also involves a theoretical shift in how we think about the representation of space.

For European cinema post-Wall, new works of mapping were necessary in order to inscribe new kinds of space—as Eastern and Western Europe gave way to more complex political landscapes, cinematic space became a key territory in which change could be imagined. Thus, while the previous chapter took literally the concept of a “political landscape,” this chapter is more concerned with the spirit than with the letter of that phrase, turning to films that rethink the political, rather than the physical, map of Europe. Of course, the distinction between physical and political mapping is always to some extent a fiction, for, as we have seen, even an image of nature is implicated in a structure of historical and social meanings. Nonetheless, there is a difference in cinematic terms between the landscape image and the more conceptual landscape of national and international space. These kinds of spaces are never directly visible, but, as with Harley’s critique of cartographic textuality, they must be carefully read. In what follows, I trace both a filmic and a critical path, considering how theories of space and spatial representation, as well as art cinemas, provide forms of textuality in which we can engage the changing map of Europe.

Questioning the Map

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s witty exchange has more than a rhetorical connection to these issues, for the film version of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead is an early example of post-Wall and postmodern European art film. The film traces the trajectories of two minor characters from Hamlet in the interstices of known history. Located somewhere between the heritage literary adaptation and the self-referential art film about art (similar to the later Shakespeare in Love [Madden, 1998], coscripted by Stoppard), Rosencrantz and Guildenstern narrates the unsuccessful attempts by Shakespeare’s minor characters to figure out what their purpose is and who is pulling their strings. The film opens with the two men trying unsuccessfully to remember anything before being summoned that morning to see the king. Upon arrival, their movements weave in and out of the better-known events at Elsinore. Behind the scenes, as it were, they try to make sense of what little information they have been given. As it turns out, paranoia is not an unreasonable response to events, since, as the knowledgable spectator already knows, our heroes will be sent to England with a sealed letter requesting that the king execute them. As the traveling Player tells them: “The bad die unhappily, the good unluckily: that is what Tragedy means.”

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern can provide a useful bridge between the popular forms of the heritage history film and a more specialized art cinema. The film draws from the conventions of the British literary adaptation, which is closely related to the heritage film. (The adjacence of these forms in British cinema occurs both because the canon of English literature is commonly adduced to the category of “British heritage” and because many defining texts of the heritage genre are themselves literary adaptations. See, for instance, A Passage to India [Lean, 1984], Maurice [Ivory, 1987], and Howards End, all from E. M. Forster novels.) Thus, Rosencrantz’s Shakespearian language, historical setting, and supporting cast of respected theatrical actors are easily readable in a heritage framework. The world of Hamlet’s narrative resembles a nonexistent Shakespeare adaptation, perhaps directed by Kenneth Branagh. But, just as the play’s characters move uncertainly around the edges of Hamlet, the film’s leads, Tim Roth and Gary Oldman, are film actors, thrust into a theatrical world, lost in the diegesis of heritage. By bracketing the world of Hamlet as incomprehensible to the protagonists, the film constructs a self-reflexive and art-cinematic play on the heritage genre.2

In fact, the film’s art-cinematic form focuses on this self-reflexive play with representation. Its structuring joke is that, as fictional characters, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern have only the few lines of Hamlet that mention them from which to draw their identities and knowledge of the world. Before they were awakened by the king’s messenger, they literally did not exist. This premise enables a complex staging of fictional space, in which the spectator’s knowledge of Hamlet is constantly refracted in a proliferation of narrative forms. Most simply, the spectator frequently knows more than do the characters, as when they try, unsuccessfully as usual, to figure out what is wrong with Hamlet. And throughout the film, reflexivity is foregrounded, as when the players mime the plot of Hamlet for the castle’s servants, or when the play within the play includes within it yet another play, this time a puppet show. Fictional spaces multiply, and within this prison house of representation, the real place of England becomes an uncertain abstraction.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s existential dilemma irresistably invokes contemporaneous work on postmodernity. We may be reminded, for instance, of Jean Baudrillard’s well-known reading of Jorge Luis Borges’s story “On Exactitude in Science,” in which an empire creates a map the same size as its territory, only to abandon the map and let it rot across the far corners of the nation.3 For Baudrillard, even this decay of representational truth does not go as far as the postmodern condition of simulation, in which there is no longer a referential ground for the image. The simulacrum precedes and, indeed, replaces real space. However, while there is no outside to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s fictional Denmark, the film does not, like Baudrillard, reject any notion of reference. More significant here than the theory of simulation is the place that cartography holds within theories of representation. In conjuring the postmodern condition, and even though he immediately claims that the allegory is false, Baudrillard is compelled to begin with the image of a map.

A more suggestive contemporary account is Fredric Jameson’s discussion of cognitive mapping, in another of the canonical texts of postmodernity.4 Jameson also uses cartography as a way to imagine a post-modern relationship to spaces, but in citing Kevin Lynch’s term, he stresses the political implications of mapmaking. Beginning with the shift from subject-centered itineraries and sea charts to modern star maps that enable a relationship to totality, Jameson suggests that the postmodern subject is, like the pre-modern one, faced with a space that cannot easily be totalized. Thus, he claims, “the conception of space that has been developed here suggests that a model of political culture appropriate to our own situation will necessarily have to raise spatial issues as its fundamental organising concern.”5 He goes on to suggest that this new cultural form could be defined as an “aesthetic of cognitive mapping,” a form that attempts to give shape to new structures of complex totality. This idea, that a textual aesthetic of mapping might be required in order to reimagine social space, offers one way to connect theories of postmodernity to the cultural spaces of post-Wall Europe.

In the case of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the terrain being mapped is in the first instance textual: the film reimagines the fictional space of Hamlet rather than any actual location. Just as Jameson’s subject makes mental maps in order to navigate the postmodern city spaces of Los Angeles, so Rosencrantz and Guildenstern struggle to find a way through the text of Hamlet, unable to see from the bird’s-eye vantage point of the spectator, who knows where this is going. But if Rosencrantz does not believe in England, the film does, for it is the social space of Hamlet, Shakespeare, and the British heritage film that is being redrawn here.6 Moreover, while Stoppard’s original play, written in the 1960s, stages a vertiginous hall-of-mirrors discourse on theatrical space, the film version, like Siegfried Kracauer’s real trees, prompts an intrusion of material reality. Unlike Kracauer’s examples, Rosencrantz plays on this juxtaposition of actual and fictive spaces: in keeping with Rosencrantz’s skepticism, we never see England. And in a refusal of heritage logic, the film was not shot in either Britain or Denmark but in Slovenia, Croatia, and Yugoslavia. This geographic replacement is visible in the architectural style of Elsinore, in the central European aesthetic of the puppets, and in the ethnic appearance of the Balkan actors who play the players. With this eruption—in northern Europe—of these signifiers of southeastern Europe, the film’s real spaces complicate its fictional discourse on cultural power and national identity.

This kind of second-order mapping, in which it is not a country or region that is reimagined but an image of national culture, becomes particularly important in British cinema, where the canon of literary history has been central to competing discourses of national identity. Here, Stoppard can be placed alongside Derek Jarman, whose Edward II (1991) reimagines Christopher Marlowe’s play from a queer perspective, or Peter Greenaway, who deconstructs the heritage image in Prospero’s Books, a complex digital transformation of Shakespeare’s last work. In all these films, the language of the source text is left almost untouched, while the image track constructs new and often radically different meanings. In Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, line readings of Hamlet’s text throw identity into doubt, with intonations that imply that nobody has any idea which character is which. Thus, the literary texts form a ground, a national landscape that cannot be remade but can be reenvisioned, made to speak otherwise.

In its self-conscious play with space, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern exemplifies the beginning of a process of textual mapping that we can trace across European cinemas in the 1990s. Much like the film’s hapless philosophers, post-Wall art cinema has two structuring problems: the ontological and the epistemological. Simply put: What is Europe, and how can we understand it? While there is clearly no singular response to these questions—European art cinema is as diverse as ideas of Europe—we can borrow Jameson’s claims about cognitive mapping in order to clarify the ideological stakes of posing the questions. For Jameson, mapping “allows us to rethink these specialised geographical and cartographic issues in terms of social space—in terms, for example, of social class and national or international context, in terms of the ways in which we all necessarily also cognitively map our individual social relationship to local, national, and international class realities.”7 The sections that follow consider how post-Wall art cinema maps several kinds of socially determined spaces: city and national spaces, spectacular space, international space, and borders. What connects ontology with epistemology for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern is, in the inexorable logic of literary history, death. As we shall see, in post-Wall art cinema, too, the redrawing of space and time often juxtaposes textual play with historical finality.

Reading Space

In the twentieth century, space emerges as a central term in theorizing modernity and, later, postmodernity. While the field of spatial inquiry is too vast and too multidisciplinary in nature to attempt to cover here, it is useful to chart some of the routes by which space becomes such an important category to contemporary cultural studies. As we have seen in the previous chapter’s discussion of Walter Benjamin, the work of the Frankfurt School is central in articulating the relations among space, time, cinema, and modernity. However, Anthony Vidler maintains that, until recently, the importance of space to the Frankfurt School was often downplayed: “On one level, of course, it is already a commonplace of intellectual history to note the fundamental role of spatial form in the cultural analyses of social critics like Theodor Adorno, Siegfried Kracauer and Walter Benjamin…. And yet it is true that the central position of these spatial paradigms in the development of critical theory has more often than not been obscured by the equal and sometimes opposite role of temporality, of these theorists’ concern with historical dialectics.”8

What prompts a return to the theorists of space in modernity is, at least partly, the renewed importance of space as a defining feature of postmodernity. We have already considered Jameson’s claim that cognitive mapping is the only means to produce a politically engaged post-modern culture, as well as Baudrillard’s use of the ruined map as a metaphor for the loss of reference. In addition to these texts, many areas of postmodern criticism, philosophy, and social theory emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century, often influenced by Henri Lefebvre’s seminal work, The Production of Space. Lefebvre argues that space must be understood as socially produced, and it is particularly in the area of critical geography that this approach helped define new paradigms of thinking space. David Harvey, to take one example, proposes that the condition of postmodernity is defined by a new emphasis on space over time, while Edward Soja and Charles Jencks theorize urban spaces and architectural style, respectively.9

What makes these social theories useful for considering filmic space—beyond their broad claims to describe the spatial experiences of modern life—are the ways in which contemporary critical theory has begun to articulate connections between globalized postmodern space and various material fields of spatial production: art, architecture, cinema. An early example of this kind of work is Jameson’s reading of post-modern culture, but as the debate has matured, more medium-specific analyses have emerged, most significantly in art history. This critical terrain develops the debates on modernity into the contemporary era and has two signal advantages for cinema: first, it offers ways to think about cultural texts in relation to evolving geopolitical spaces, and, second, it simultaneously mounts critiques of those geopolitical and geographical systems with which it must engage.

For example, Victor Burgin argues in In/different Spaces that the social scientific versions of postmodern geography—Soja, Mike Davis—fail to consider the work of fantasy in the social production of space, or, in Lefebvre’s terms, that they consider only spatial practice, not representational space. In thinking artworks spatially, he maintains, we must add back the psychic investments that geography strips from the experience of place: subjectivity, desire, identification. In a similar vein, Rosalyn Deutsche criticizes David Harvey’s account of postmodernity as masculinist and totalizing, ignoring the crucial influence of feminism in developing postmodern culture and theory. Her examples include feminist artists such as Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger, but she is equally concerned with the ways in which feminist theories demand a more situated and political perspective on the contested interfaces of public art and urban space.10

These art historical readings of the geographic suggest, if not a model for approaching cinema, then certainly a significant area of disciplinary overlap. As Irit Rogoff argues, “We must recognize geography to be as much of an epistemic category as gender or race, and that all three are indelibly linked at every stage.”11 In her study of mapping in contemporary art, Terra Infirma: Geography’s Visual Culture, she argues persuasively that cartography—the visual rendition of geographic spaces—is not simply a metaphor or theme but, rather, a central category of understanding subjectivity, history, and representation. Rogoff, like Harley, points to the place of maps in condensing power: their ability to name, write, and organize social spaces and their history in colonialism and the narration of the nation-state. Analyzing the political work of artists such as Mona Hatoum, Hans Haacke, and Joshua Neustein, Rogoff reads artistic remapping as a kind of countercartography, a disturbing of identity and hegemonic power. Understood this way, cultural texts that foreground geographic representations might offer a productive way to interrogate the politics of contemporary space.

While this kind of political remapping has become a major strand of contemporary art, it is less dominant in cinema. However, Rogoff’s argument is suggestive for cinema studies, particularly in its refusal to use any positivist notions of geography. Echoing Jacques Derrida in The Other Heading, she links geography to ethics, stating that “it seems imperative to shift from a moralizing discourse of geography and location, in which we are told what ought to be, who has the right to be where, and how it ought to be so, to a contingent ethics of geographical emplacement in which we might jointly puzzle out the perils of the fantasms of belonging as well as of the tragedies of not belonging.”12 Thus, it is not the case that cartography suggests a new and improved cinematic map of Europe, but that we might find a new ethics of mapmaking, a countercartography of European identity.

Hara-kiri in Berlin

One film that engages with this task is Berlin.killer.doc (Ellerkamp and Heitman, 1999), which works (and plays) on the spaces of Berlin in “the interim.” The film is constructed a little like an experimental reality-TV show avant la lettre: a group of real characters sign up for a citywide game of “killer,” the children’s game in which each player is contracted to “kill” another one. The protagonists then make film or video diaries, recording their experiences as both murderer and victim as they traverse the spaces of the transforming city. The film’s narrative immediately proposes a work of remapping, as the opening sequence introduces not only the characters but also the building sites of Berlin’s Mitte. The interim describes the time in which post-Wall Berlin is being remade politically, culturally, and architecturally, and the film superimposes on this public remapping a more subjective and marginal cartography.

This subjective relationship to space underpins the film’s cartographic logic, for we quickly leave behind the grand architectural projects mushrooming across the Mitte in order to focus on small-scale, deliberately inconsequential actions. Each killer must follow his or her victim, and thus we accumulate sequences shot by players walking in streets, conducting surveillance in bars, and idly watching apartment buildings. The defining modern figure of the flaneur is updated and imbued with both boredom and threat.

Characters undertake tedious stakeouts of each other, and in a climactic scene, two stuffed rabbits belonging to a Japanese woman named Akiko are kidnapped. To save her bunnies, Akiko must agree to commit hara-kiri in a kitschy midnight ceremony. In this storyline, the kawaii subculture of Japanese cute aesthetics trumps the monumental scale of Berlin’s urban spaces.

Berlin.killer.doc Berlin’s urban spaces are framed in the process of transformation. (Courtesy Bettina Ellerkamp and Jörg Heitman)

The film creates several alternative cartographies. Most direct is the encounter with in-between spaces, where the game prompts interactions between players and semiotically loaded city spaces. One character films himself sitting in waste ground, talking about the huge empty spaces to be found in Berlin, what Andreas Huyssen has called its “voids.”13 Others describe Berlin’s provincial character and their fears that it will be lost among the featureless global architecture that is proliferating. In one scene, a victim goes to hear a reading in the Jewish cemetery, held in response to racist attacks on the site. The murderer spies on his victim through a hole in the wall, and we cut between shots of the hole and the victim. The scene follows on from another player’s discussion of Berlin as a city that contains all of twentieth-century history compressed in one space. Along with the political weight of the reading, this conjunction implies for the image of the hole a historical significance, another “void” of Berlin. It is also, of course, a returned gaze. We know that the killer is looking through the hole, that there is now a subject for this historical void.

Berlin.killer.doc Akiko commits hara-kiri to save her bunnies. (Courtesy Bettina Ellerkamp and Jörg Heitman)

The structuring logic of the “killer” game also produces an alternative method of mapping: the trope introduces a fundamental element of chance into the film’s representations. Any character may be killed at any time, and both the locations and actions of the film are improvised by the actors. Berlin becomes a city organized solely by the artificial and aleatory system of the game. Thus, Berlin.killer has intimations of automatic writing and Berlin’s Dada history, but it also suggests the immaturity of the new city, as with a child using games to explore identity and transgression. Of course, the element of chance is also an element of crime—the film’s Berlin is subject to sudden and inexplicable violence. With car bombs and letter bombs, many of the “murders” evoke Germany’s recent history of domestic terrorism, as well as broader specters of global violence. But framed by the fictional game, these references become reflective rather than visceral. As a place in flux, Berlin reverberates with echoes of the crimes of elsewheres and elsewhens.

Finally, the film’s formal structure raises the question of the document: How is it possible to record Berlin’s fragmented and rapidly changing present? How does one document identity in flux? The answer is twofold: a self-referential accretion of documentary forms, and a representational play of fiction and reality. The documentary forms derive from the diaries of the players, as well as from the third-person narration of the film. They include super-8 film, video, and still photography, as well as other types of document, such as the digital file that names the film, the game’s Web site, and the time, date, and place stamp that recurs on the image. The spectator cannot take any of these “documents” as direct accounts of reality, since each is seen to be partial and mediated. Furthermore, each document is partly documentary and partly fictional, since the game narrative mixes social actors with a highly fictional murder narrative. This contradictory relationship to the real is condensed in the murder scenes, where moments of pure fiction intrude into the documentary narrative. In one such scene, a car explodes; in another, a staged car crash depicts fake blood. Instead of the fictional films with moments of indexicality (as discussed in chapter 2), here we have a nonfiction film with arresting, disjunctive fictive images.

Berlin.killer creates a countermap of Berlin space, at the level of both content and form. Out of the self-styled center of the new Europe, the film conjures a place of unbelonging as much as identity: players come from England, Japan, and the United States, as well as from the city’s former West and East. And once part of the game, characters must contemplate not just the journeys across the city that their diaries will describe but their ontological status. What is the new Berlin becoming, and how does one exist here? Thus, as one character draws a route in thick black pen across her map of Berlin, she considers her killer-Dasein (killer-being), questioning how one can define oneself in relation to both the Other and the city.14 In Deutsche’s and Rogoff’s terms, this cartographic strategy replaces masculinist totality with a feminist-influenced emphasis on the partial view. Moreover, the film extends this critique in film-specific ways, setting in motion a narrative that weaves itself out of trajectories of power and vision. The film creates a map based on the place of looking relations in any organization of social space.

Cinematic Cities and Nations

Although the influence of spatial theories has been felt more in the field of art history than in film, there is a substantial critical discourse on cinematic representations of the city. From Weimar cinema on, the city has been a central figure in modernist art cinema, as well as a common location for popular European films. And the centrality to cultural studies of theories of modernity has ensured that concepts like the flaneur, the metropolis, and the street have recurred in European film theories and histories. Giuliana Bruno, who has written widely on the topic, cites a history of city films and modernity, from early panoramic views through Dziga Vertov, F.W. Murnau, and Pier Paolo Pasolini.15 Similarly, in an overview of the cinematic city, Stephen Barber describes a trajectory of urban displacement and alienation related to changes in city planning in postwar Europe. He narrates a history from neorealism through revolution and instability in the 1970s to contemporary postcolonial malaise.16

Barber suggests that the cinematic city has recently addressed the events of 1989, with Leos Carax’s Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (1991) using the ebullient street celebrations of France’s bicentennial to figure the fall of the Wall. Certainly, not every film set in a city can be read this way. But neither is Berlin.killer.doc an isolated example of the cinematic connection between the city and contemporary Europe. In a more traditionally Marxist vein, The Town Is Quiet (Guédiguian, 2001) analyzes the race and class fractions of postcolonial France by means of a cross section of life in Marseilles. The characters represent social types—we have the yuppie wife, the black kids who rap, the prostitute, and so on—but Marseilles stands as the film’s central figure, connoting a dispossessed working-class, immigrant population and France’s messy, South-facing aspect. Repeated lengthy pans across the city’s harbor locate the various social groupings within the same profilmic space, if not the same social universe. And, perhaps in a nod to The Conformist, repeated renditions of the “Internationale” by various characters link the narratives to a melancholically lost leftist past.

In their tones of euphoria and melancholia, both Les Amants du Pont-Neuf and The Town Is Quiet point to the role of emotion in post-Wall cinematic spaces. Unlike the more stoic texts of the European New Waves, contemporary art films often play with melodrama and affect. This question of emotional landscapes has been examined by Giuliana Bruno in the evocatively titled Atlas of Emotion. Bruno is one of the most prominent film theorists to write specifically on space, and, as one might imagine, she locates film geographies alongside artistic ones. She shares with art historians like Rogoff an interest in alternative maps, pointing to both paintings and films as modes of writing in which counterhegemonic journeys might be undertaken. However, Bruno is specifically concerned with relationships among films, social spaces, and the body—architectures of emotion that she names “intimate geographies.”17 Her readings range from domestic architecture to international journeys, but, like Burgin, Bruno demands throughout that we think of textual journeys in terms of desire.

We can trace these political and yet intimate geographies in films that map the nation, as well as those centered on cities. Bhaji on the Beach, a popular example of new British filmmaking, reimagines the traditionally white seaside resort of Blackpool as a multicultural space through a day trip taken by a South Asian women’s group. Positioned as a feel-good comedy, the film’s title sets up a comic juxtaposition between Indian and British traditions. And, although its narrative touches on social issues such as interracial romance, intergenerational conflict, and white racism, the film constructs identities as much through a mobilization of cinematic spaces as through these narrative conflicts. In several sequences, an Asian woman named Asha is romanced by a white man in parodies of Hindi film styles. Some of these sequences refer to classic Indian films, while other, more comic scenes show the white suitor in “Indian” make-up, enacting a Bollywood-esque musical number. While these sequences represent Asha’s Hindi film fantasies, her paramour typifies a fading northern English tradition of seaside theater. Declaring that Blackpool looks “just like Bombay,” the film quite overtly globalizes British national space, playing with the perils and pleasures of national identity.18

Bhaji on the Beach Blackpool’s kitschy seafront is compared with Bombay.

Other national examples of remapping abound, often connected, as with Bhaji, to the conventions of the road movie. Narratives that traverse national spaces enable a discourse on the shape and nature of the nation. An example from France is The Adventures of Felix (Ducastel and Martineau, 2000), in which Felix, a young French North African man, decides to hitchhike from Brittany to Marseilles to find the father he never knew. Like Bhaji, the film fits easily into a liberal multicultural discourse: besides being North African, Felix is gay, and en route he encounters racism and homophobia, as well as more life-enhancing examples of the French rural public. Away from the road movie genre, the films of J. J. Bigas Luna have been argued by Paul Julian Smith and others to articulate Catalan national identity.19 While films such as Jamón, jamón (1992), Golden Balls (1993), and The Tit and the Moon (1994) are often viewed as typical Spanish sex comedies, Smith points to their parodic mobilization of landscapes and stereotypes as a politically acute vision of contemporary Catalonia. In all these examples, sexuality works to negotiate between the body and political space, producing intimate maps of the contemporary nation.

Of course, not all geographies can be understood in the self-contained modern spaces of the city and the nation. Burgin points to the importance of fragmented spaces in postmodernity and connects this to recent theorizations of the exile, the foreigner, and the Other.20 And, in his Atlas of the European Novel, Franco Moretti makes maps of the urban, trans-European, and colonial routes through which the modern novel passes.21 These issues have become increasingly important in European cultures, as the growth in the number of films about immigration, postcoloniality, and minority communities demonstrates. More important than simple representation, though, are the ways in which films figure complex relationships to spaces of belonging. Irit Rogoff asks: “Can terrains and topographies and landscapes have a double consciousness, a mutual inhabitation?”22 Her examples are African-American art, but we could as easily think about Black British film or the double nomenclature of “Eastern Europe” as opposed to “Europe.”

One film-based study that takes up this kind of “uncanny geography” is Hamid Naficy’s An Accented Cinema, which uses language as a metonym of exile, diaspora, and immigration.23 For Naficy, the stylistic accent marks the trace of double consciousness in diasporic cinemas. A European example of this structure is Turkish German film. Here, feminized space is crucial, echoing Deutsche’s claim that we must think postmodern spaces through gender. Naficy points out how many Turkish German films focus on the ways in which Turkish women are trapped within domestic spaces, reading interior locations and constricted framing as a condensation of both the women’s limitations within traditional Turkish cultures and their limitations within Germany (refusal of citizenship, prejudice against Muslims, demand for assimilation). Both Berlin.killer.doc and Turkish German films point to the transnational elements of the national film, especially in post-Wall Germany. However, to address Europe as a supranational space, it is necessary to think beyond the nation and to consider the category of the international in European film production.

Inter-, Supra-, and Transnational Space

The mapping of spaces larger than the nation raises the issue of international coproduction, a structure that enables an institutional, as well as a textual, production of space. Coproduction is neither new nor uniquely European. Moves toward greater cooperation in film production among European countries began in the 1940s, and by the early 1950s the Western European Union, one of the precursors to the European Union (EU), funded noncommercial films made by more than one member state.24 Today, coproduction is common across the world, with American, European, and Asian countries, for example, joining forces to gain wider funding and distribution for projects with a culturally diverse appeal.25

What often links these various examples of coproduction is a principle of cultural value, in which coproduction is supposed to support film projects that might not otherwise be commercially viable or to enable national cultures to be more fully represented in film. Although they are inherently international, coproductions have historically been encouraged by national governments in Europe, which regarded supranational funding and production bodies as part of what Steve Neale calls “the promotion and development of national Art Cinemas under the aegis of liberal-democratic and social democratic government.”26 Thus, coproduction is industrially and ideologically linked to the concept of art cinema, and from the beginning it brought the international nature of the medium into a tension with discourses of national cultural identity.

As art cinema changed in the 1980s, so did coproduction. With an economic squeeze on many domestic industries, and political moves toward increased European cooperation, coproduction grew rapidly. John Hill cites an estimate “that while only 24 (out of 781) films made in Western Europe in 1975 were international co-productions this figure had risen to 203 (out of 552) by 1991.”27 And Angus Finney confirms the continuation of this growth through the 1990s, reporting that coproduction accounted for 12 percent of total European production in 1987 but that this figure rose to 37 percent by 1993.28 This shift brought a change not only in the national origin of funding but also in the nature of its sources: as Terry Illot points out, most of the new sources were television stations and European subsidies. Thus, in 1994, 65 percent of all European films in production had some kind of subsidy money, and 51 percent had television funds.29 New European initiatives include MEDIA, a plan from the European Union to stimulate production with loans and subsidies for scripting, production, distribution, and promotion, and the Eurimages fund, which is part of the Council of Europe and funds films made by three or more member states.

The expansion of these kinds of programs is clearly linked to the increasing interconnection of European countries and the rise in the years approaching 1992 of a liberal discourse on the European project. While EU membership was limited in the 1990s to west European nations, cinema and television organizations worked more rapidly toward a broader idea of European identity. Thus, Eurimages included east and south European countries such as Poland and Turkey, and the European Broadcasting Union’s membership stretched from Iceland to Morocco.30 Seen in this context, the rise of coproduction in the late 1980s derives both from a new discourse of European filmmaking as a cultural project (as distinct from previous concerns for national filmmaking in Europe) and from the necessity of partnerships to gain funding. Thus, we can read coproduction as both a financial and a cultural imperative, inherently related to questions of European identity, audience, and textual address.

The idea of a specifically European film has had many detractors, however. Both leftist and conservative critics have dismissed what they see as a bourgeois and bureaucratic vision, in which the coproduction is understood as filmmaking by committee. The leftist critique is exemplified by Cahiers du Cinéma critic Antoine de Baecque, who views the problems with European film as overlapping with that of the contemporary art film; it has become safe, characterized by a homogenous beauty without distinguishing features. He identifies this retreat from radicality as another problem of heritage culture, arguing that the new European film is too smooth, domesticated by the beautiful image.31 The fear is thus not of European cinematic identities per se but of a false identity, in which all films look the same and national or cultural differences get ironed out in a homogeneous bourgeois aesthetic. The name given to this (perhaps chimaeric) bad European film is the Europudding.32

For Serge Toubiana, also writing in Cahiers, this problem is symptomatic of a shift away from the European art cinema of auteurs. He argues that only politicians, funding groups, television companies, and technocrats have a stake in an idea of Europe, while filmmakers tend to be more interested in the specificity of time and place. They speak of the local and the singular, while films that attempt to produce a European vision after the politicians’ desires become overcooked Europuddings.33 Thus, the discourses of European cinema follow those of the contemporary art film, but in this case, the critique of the image is linked to the problematic nature of European-ness, not just to aesthetic and political reaction. Toubiana is correct in his assertion that many recent European films do not construct themselves as European; coproduction notwithstanding, they work to represent a singular national culture. Sally Potter’s Orlando (1992), for example, is a British, Russian, French, Italian, and Dutch coproduction. But with a British director and star, and a narrative that adapts a British novel about British history, the film scarcely offers a broadly European perspective. Or, to take another auteurist example, Ulysses’ Gaze (Angelopolous, 1995) was cofunded by Greece, France, and Italy, but despite its international cast and crew, the film’s focus on the Balkan landscape and identity grounds it in Greek director Theo Angelopolous’s nationally or regionally specific concerns.

Chantal Akerman articulates this position directly: “I don’t think there is such a thing as European identity. The reasons why this question has arisen are, on the one hand, the increasing global dominance of Hollywood, and on the other, the existence of the European Community and its ability to put money into European co-production.”34 On the one hand, this is a commonsense truth, as, of course, there is no such thing as a singular European identity, objectively existing and available to all European spectators. On the other hand, this very fact provides a potentially more interesting insight into the problem of coproduction than Akerman’s practical attitude suggests. European-ness in the 1990s is at once a much desired mode of identification and an impossible one. Unlike national identities, which became increasingly naturalized in this period while often criticized, supranational identities are lauded in the public sphere but less popularly available.35 And art film, with its historical project of representing national cultures, alongside its new situation of international production, is central to this paradox. Caught among highly national markets and international funding, the European ideal and fear of the Europudding, coproduction has a unique relationship to European identity.

In his discussion of the concept of national cinema, Philip Rosen points out that many of the more rigorous studies of national cinemas have had a diachronic element, not claiming that all films made in a country are national but, rather, that at particular historical moments the national emerges more forcibly.36 If we can extend this formula to include a supranational space, then the 1990s were such a moment for the idea of European cinema, even if the nature of this new discourse on the European is precisely defined by its difficulty or even its impossibility. Only once coproduction had become such a dominant part of European filmmaking practice, and only once the end of the Cold War and the expansion of the EU had made the idea of Europe once again culturally and politically central, could a cinematic discourse of European-ness emerge. In this new cultural context, European identity becomes a structural problem for the coproduction.

What happens increasingly is a textualization of this problem. A key example of this change is Zentropa, a German, Danish, Swedish, and French coproduction that uses a web of intertextual references to textualize its hybridity. (In chapter 5, I discuss this film in more detail.) Such references are often dismissed as postmodern window dressing,37 but I would suggest that referentiality here indicates the way in which art cinema can no longer take for granted its part in a European culture. In the context of both the new Europe and the postcolonial critique of Eurocentrism, Europe is no longer able to function as the unmarked center for an art cinema that pretends to universality. Zentropa, therefore, constantly recapitulates its cinematic heritage, marking its European origins in a way too excessive to be naturalized. It refers to a pantheon of European art film stars in its casting: the film is narrated by Max von Sydow; its femme fatale is played by Barbara Sukowa, frequent collaborator with Werner Rainer Fassbinder; and the American general is Eddie Constantine, best known for his role in Alphaville, a Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution (Godard, 1965).

This homage extends to the crew also, as the cinematographer, Henning Bendtsen, worked with Carl Theodor Dreyer, for whom he shot Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964). In addition, the film is full of textual references, particularly to films made in the late 1940s, the time that the narrative is set. Examples include Germany Year Zero (Rossellini, 1948) and The Third Man (Reed, 1949), from which the film takes the narrative of denazification and the innocent American hero in a zoned city, respectively. This obsessive marking of historical origins even extends beyond the period of the narrative, where the film’s noirish mise-en-scène cites German Expressionism—the hypnotist character, for example, reminding us of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (Weine, 1920).38 And, of course, such markers can be read geographically too, citing Swedish, German, French, Danish, Italian, and British cinemas. These references no longer function as signs of art cinema in general but are reinserted into a geographically and historically specific system.

Even films that are not such mixed coproductions textualize European transnational space. Lovers of the Arctic Circle (Medem, 1998), for example, is a Spanish and French coproduction, but it charts an itinerary from Spain to Finland, in which its lovers traverse the continent without meeting. Journeys across Europe are central: one protagonist, Otto, becomes a pilot so he can more easily cross European spaces, while for Ana, the Arctic Circle is a fantasmatic space, a projection of fantasy identification from the Mediterranean to the frozen north. This imaginary space is specifically European, for the emigration of Ana’s mother to Australia is dismissed as “too far.” The film is concerned with charting the psychic territory of Europe: Finland and Spain are as far apart as it is possible to be within Europe, but not the “too far” of another continent. With the lovers journeying to the ends of the continent to find each other, this, to be sure, is an intimate geography.

European spaces both contemporary and historical take on a quality of fantasy, as locations in which the lovers’ narratives intersect. The film structures both a temporal and a spatial axis of causality: the historical narrative connects a German and a Spaniard who met during the Spanish Civil War with their respective grandchildren, while the spatial axis traces the main characters’ journeys from Spain to the Arctic Circle. The encounter in the 1930s works out better than expected, as the young Spanish man saves a German soldier, who responds to this kindness by deserting and marrying a Spanish woman. The apparently easier contemporary relationships are thwarted, however, as childhood sweethearts Ana and Otto cannot find each other and are framed together only when we see the reflection of Otto in Ana’s dead eyes. Despite the apparent ease of modern travel, creating a European union proves more difficult than it was during wartime.

Lovers of the Arctic Circle The Arctic Circle runs through the middle of Ana’s cabin.

A romance like Lovers of the Arctic Circle may seem distant from more politically engaged art-cinematic texts like Berlin.killer.doc. But the transnational is always connected to the local, and fantasmatic spaces are no less implicated in politics. We might consider, for instance, that Julio Medem, the director of Lovers, also directed The Basque Ball: Skin Against Stone (2003), a controversial documentary on the Basque separatist movement. Across these texts, relationships among local, national, and European identities can be traced, and the idea of Europe as a spatial-historical object, the literal and figurative image of Europe, begins to be worked on in cinematic terms, as a question of image and narrative, space and time.

Spectacular Politics

In considering the cartographies of European art cinema, the question of spectacle becomes politically central. As we have seen, spectacle is a significant issue in the largely pessimistic body of work on contemporary art cinema. Whereas Neale cites as characteristic of 1960s art film “an engagement with the look in terms of a marked individual point of view rather than in terms of institutionalized spectacle,”39 most of the critics of 1980s and 1990s film specify a turn toward the spectacular as the defining shift in the post–Star Wars art film or in contemporary film tout court. Thomas Elsaesser argues that instead of resolving around metaphysical themes, the contemporary art film turns inward: “Authority and authenticity lie nowadays in the way film-makers use the cinema’s resources, which is to say in their command of the generic, the expressive, the excessive, the visual and the visceral.”40 Michel Chion has coined the term “neo-gaudy” to critique the “formulaic aesthetic” of recent European art film.41 As with heritage films, contemporary art films are often negatively compared with the allegedly more radical films of a generation earlier.

This critical move is part of a larger theoretical problem around spectacle, and we have seen an example of its operation with regard to the critical reactions to the Italian heritage films, in which the beautiful image was argued to “fall out” of the narrative, blocking any political meaning the film might otherwise have contained.42 However, this tendency to separate form from content, spectacle from meaning, takes on a more overtly political valence with regard to art cinema, and especially art films that thematize historical change. Thus, films that address Cold War history directly are frequently judged according to how they mobilize the spectacular image. An illuminating case study of this question is Emir Kusturica’s Underground. (In chapter 4, I discuss this film in more detail.) No doubt because the film was perceived precisely as “serious” and “historical” art cinema, criticism of its spectacularity focused not on the question of cliché or the touristic but on the politics of its representations. And because of the continuing violence of the wars in Bosnia, the film found itself in the middle of an international controversy, debated by philosophers and public intellectuals from all over Europe.

The debate began in the wake of Underground’s winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1995, which was perceived by some to be a sympathy vote for a film from the war-torn former Yugoslavia. However, Montenegrin critic Stanko Cerović denounced the film and Kusturica’s public actions and statements as partisan, exhibiting Serb nationalist tendencies, bias against Croats and Slovenes, and implicit support for Slobodan Milošević’s war in Bosnia.43 He further contended that the west European film community was too ignorant about the former Yugoslavia to notice this ethnic stereotyping44 and had gotten its praise politically wrong. This argument was taken up by some French philosophers, most notably Alain Finkelkraut and Bernard-Henri Lévy. In response to their very public attacks on the film, various west European writers, including Hans Magnus Enzenberger and Serge Regourd, rushed to defend the film.45

What is striking about this debate is that it did not resolve into two competing ideological readings of the film but opposed those who read the film only as an encoded political statement to those who defended the aesthetic freedom of the artist. The film’s defenders for the most part did not refute any of the political claims of Cerović and Finkielkraut but instead stood as fellow artists defending free speech and an “art for art’s sake” formalism. Regourd, for example, lauds the film for the aesthetic inventiveness of its shots and images and describes his admiration of “a rare artistic creation, an exceptional cinematic work that gives full meaning to the famous notion of ‘cultural exception.’”46 The film’s attackers, for their part, took the antispectacular separation of form and content to something of an extreme, reading the film as propaganda, in which the visual operates as a veil to hide a political message.

Dina Iordanova makes a claim to a balanced approach, and her history of the film and its impact is undoubtedly one of the most informed on the subject of Balkan history and politics. However, her account of the debate repeats symptomatically the methodology of most of the film’s critics, as when she summarizes: “Underground … came under ardent critical fire from people who claimed to be able to penetrate beyond the staggering imagery and to decipher the arcane historical and political propositions upon which the film was built.”47 Here, she clearly articulates the idea of spectacle as something to be broken through so that the hidden political meaning beneath can be seen. The image in itself becomes meaningless, forming at best a surplus and at worst the veil of a kind of cinematic false consciousness. In her own assessment, she adds the issue of history, stating that “if one leaves aside the visual particularities, Underground is a historical film which offers a clear perspective for interpreting the current violent state of affairs in the Balkans.”48 Here, historical interpretation must be separated from the visual, and thus the visual itself is defined as ahistorical. This argument combines the question of spectacle with a fairly conservative approach to historical films in which a film is read only for the historical position that can be extrapolated. It is seen not so much as a cinematic text but as a perspective for interpreting events—an argument in hieroglyphic form.

Slavoj Žižek’s ideological critique of the film is part of a larger argument about the relationship between ethnicities and capitalism, but his reading nonetheless rests on spectacle as a site of attack. He maintains that “the political meaning of this film does not reside primarily in its overt tendentiousness, in the way it takes sides in the post-Yugoslav conflict—heroic Serbs versus the treacherous, pro-Nazi Slovenes and Croats—but, rather, in its very ‘depoliticized’ aestheticist attitude.”49 I will return in more detail to the substance of Žižek and others’ ideological claims, to the important question of if and how Underground “takes sides” in the post-Yugoslav conflict. But for now I want to focus on the rhetoric of spectacle, in which there is a slippage where the political criticism is hitched to a formal strategy to which it has no necessary connection. The first part of this slippage is “guilt by association,” whereby aestheticism seems to lead directly from a prejudice against Croats and Slovenes. Whether or not this accusation of ethnic bias is tenable, it operates entirely apart from the question of spectacle: the same style could just as easily privilege another group, and, indeed, the film has been defended as not at all pro-Serb.

The second and trickier part of the slippage is between the concept of depoliticization and that of an “aestheticist attitude.” Žižek’s broad point is to attack the trend toward what he calls depoliticization, an ideological shift in which multinational capital thinks itself depoliticized, and thus ideology itself becomes the discourse excluded from the dominant ideology. Whereas ideology in the past operated to exclude some given ideological position as ideological, and therefore outside the realm of the supposedly neutral hegemony, now the claim is of an end to the era of ideologies, with any claim at all on politics being excluded from the discourse of power. For Žižek, this repression of politics only leads to the return of extremist ideologies of racism and fundamentalism, an argument that he uses to conclude that it is this Western logic of multicultural capitalism that caused the Balkan conflict, rather than ancient Balkan differences. This ideological reading is compelling, and its claims on the relationship between the West and the Balkans will become important to my argument in the following chapter. However, the theory of depoliticization is not at all connected to the idea of aestheticism, either by definition or in Žižek’s argument.

As with the question of direct political bias, the logic of depoliticization, if we can even claim it to be directly deployed in film, could be structured by a variety of formal and narrative strategies; Žižek gives no reason why an “aestheticist attitude” should be the privileged or necessary correlative for such an ideology. Furthermore, he does not expand on what he means by an aestheticist attitude, nor does he argue for its political valence in filmic terms. While we can infer that he means by the term a discourse of spectacle, of beautiful mise-en-scène, and of excess in the image, he offers no clear definition, and nowhere does he provide evidence for the claim that such an aesthetic entails the political point he derives, in fact, from narrative. His conclusion is therefore weak, based partly on an assumption that spectacle is self-evidently reactionary and partly on an analogy that cinematic excess represents, and is ultimately the same as, the excess of ethnic cleansing and slaughter in Bosnia.50 As rhetoric, this is excessive itself and does little justice to the political complexity of the cinematic image.

If Žižek’s reading is embedded in a sophisticated assessment of global capital in the 1990s, Finkielkraut takes up a more polemical version of the Jamesonian position in which spectacular cinematic historicity is a signifier of duplicity and ideological reaction.51 In Le Monde, he contends that “in awarding [the Palme d’Or] to Underground, the Cannes jury believed that they were singling out an artist of abundant imagination. In fact, they honored a servile and flashy illustrator of criminal clichés; they praised to the skies the rock, postmodern, messed up, trendy, Americanized, and shot-in-Belgrade version of the most nonsensical and mendacious Serb propaganda. The devil himself could not have come up with such a cruel outrage to Bosnia or as grotesque an epilogue to Western frivolity and incompetence.”52 Here, the rhetorical extremity of the propaganda argument becomes apparent, as Finkielkraut constructs a metonymic chain that connects postmodernity and Americanism—shorthand for spectacle in this context—with not only the irrelevant specter of “rock,” and its acolytes trendiness and mess, but also the politics of Serbian nationalism and Western ignorance. Although this listing of clichéd bogeymen could seem unconvincing when taken out of context, the rhetoric was powerful: Finkielkraut’s verdict on Underground gained ground, despite his confession that he had actually never seen the film.

Not having seen the film does not appear to have been as much of a handicap as one might expect, for the debate as a whole was characterized by an absence of textual analysis. Instead, the criticism focused mainly on Kusturica himself, with the film’s provenance as art cinema enabling an auteurist discourse in which the director’s intentions could be inferred from his personal statements and actions. This is the basis for Cerović’s scathing critique, in which he accuses Kusturica of making statements supportive of Milošević and of collaborating with institutions linked to the war. He goes on to argue that “such moral collapse could not fail to be reflected in his aesthetic meanderings, and his latest film shows real impotence masked by a firework display of noise, colour and meaningless scenes.”53 His logic is thus that Kusturica’s personal failings must, even passively, come to define his films and that the text itself is only a reflection of its ideologically compromised auteur. Spectacle is still a veil, but a veil covering not textual politics but authorial immorality.

Iordanova takes up this approach, criticizing Kusturica for having chosen to live in Belgrade rather than Sarajevo and condemning the film’s politics on the basis of an interview with the director in Cahiers du Cinéma.54 Her point—that comparing the conflict to an earthquake is problematic, as it turns planned political events into an inexplicable natural disaster—is well taken, and based on this source, Kusturica’s own opinion of the Bosnian war does not sound very politically nuanced. (Of course, it is just as easy to find a quotation to suggest exactly the opposite: in an interview in Libération, Kusturica asks, “How can we defend the idea of a multi-ethnic Bosnia if we have destroyed the idea of a multi-ethnic Yugoslavia?”)55 However, just as it is important not to read form as a veil for a hidden ideological content, so it is crucial not to let an auteurist approach prevent analysis of the film itself. This is why it is necessary to theorize Underground’s politics through the specificity of the image rather than by bypassing its form altogether.

I have spent some time detailing the debate around Underground to illustrate the imbrication of theories of spectacle in recent cinema with the historical topics and institutional forms of the films and to show how this relationship can have high political stakes. I have concentrated on the position of those attacking the film, for it is this position that most clearly takes up the film and cultural theory critique of spectacle, using it to produce what seems to me to be an inadequate and limiting political intervention. However, the defenders of the film offer no stronger method, and just as the attacks on Underground are theoretically inadequate, so are the defenses that ignore substantive issues of ideology and form in favor of an equally auteurist and politically vapid championing of the freedom of the artist. I return to the political logic of Underground in chapter 4, but for now I am concerned more with the limitations of the debate on the politics of spectacle. Thus it is necessary to escape from the confines of this circular logic and to think in a film-specific way about how post-Wall films deploy spectacle in relation to history, ideology, and European space.

The Borders of Europe

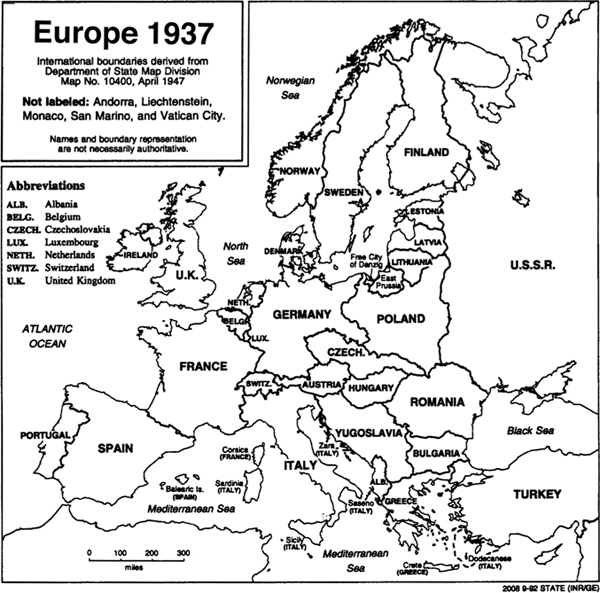

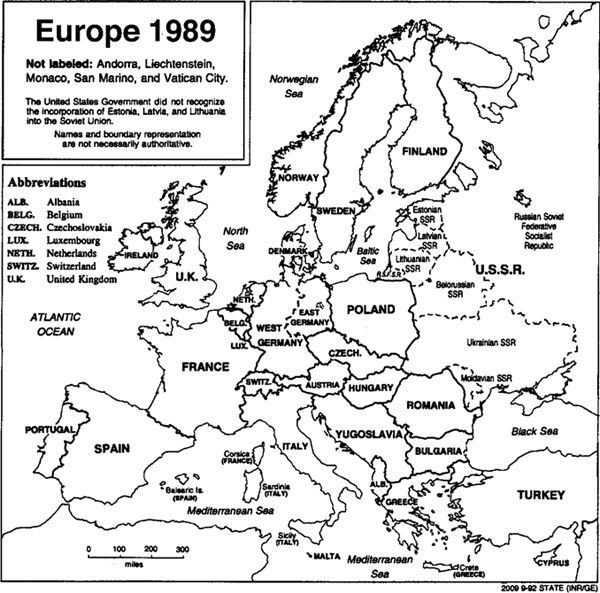

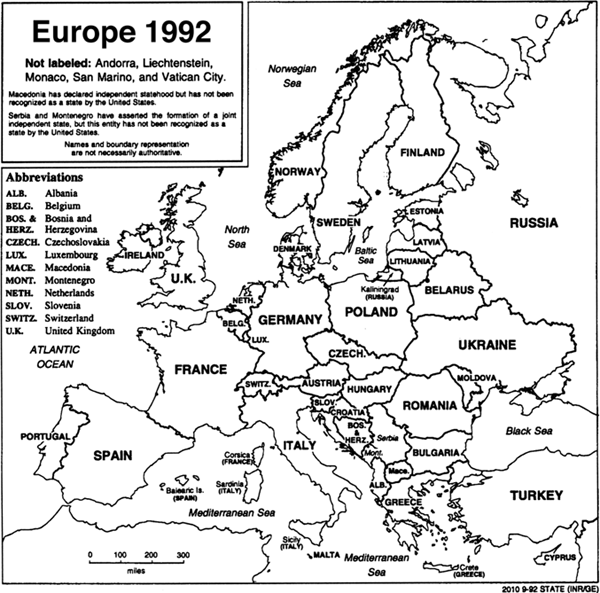

While Ackbar Abbas suggests that Hong Kong experienced in the 1980s and 1990s a sense of imminent disappearance, a disturbed relationship with its own location in space and time,56 the problem for Europe in the 1990s was not a disappearance but a reappearance of what had been there before: as the map of the continent was redrawn in the early 1990s, it came increasingly to resemble that of a historically earlier moment. It became commonplace to point out that while atlases published only a few years earlier were now substantially inaccurate, those from the beginning of the century were once again close to representing Europe, with their unified Germany, absent Soviet Union, and ethnonations in the Balkans. Thus, temporal moves forward were partially experienced as historical and spatial moves backward, and discussions around “the end of history” and the “New World Order” troped geopolitical changes in historical terms.57 This doubling back of a geographical onto a historiographical logic also describes a temporal disturbance, and one, like Abbas’s claims about Hong Kong, that is legible in cultural terms.

The boundaries are shown for Europe in 1937. (Geographical Notes 2/3, 1992. Courtesy United States Department of State, Bureau of Intelligence and Research)

Many of the films discussed earlier can be read in relation to this cultural logic; Lovers of the Arctic Circle looks back from contemporary Spain to the anti-Franco struggle, while Berlin.killer.doc traces the historical palimpsest of the new Berlin. Across Europe, 1990s films addressed the new order. In affluent northwestern Europe, themes of immigration and multiculturalism dominated, while in eastern and east-central Europe, contemporary stories about life under capitalism jostled with revisionist histories of the twentieth century. Filmmakers from various countries took on the war in Bosnia, although conditions made indigenous filmmaking a challenging enterprise for much of the 1990s. However, nowhere were these events experienced more acutely than in the countries that formed the fault lines of the old Eastern and Western Europe—countries such as Germany, the Czech Republic (Czechoslovakia), and the successor states of the former Yugoslavia—and it is in these countries’ films that we find the most acute responses to Europe’s changes.

The boundaries are shown for Europe in 1989. (Geographical Notes 2/3, 1992. Courtesy United States Department of State, Bureau of Intelligence and Research)

Films made in nations along the border of Eastern and Western Europe often render visible the difficulties and desires of this new cartography. While these countries have varied film industries and traditions, we can discern across these borders a recurrent interest in European Otherness, a desire to chart new itineraries and to see identity otherwise. An early instance of this impetus is the German documentary Videograms of a Revolution (1992), directed by Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica, in which the filmmakers compile footage shot by many Romanian groups and individuals in an attempt to document the uniquely mediatic nature of the Romanian revolution. This strategy is both alienating and affective: the spectator becomes highly aware of the position of the camera and sometimes of the danger that the cameraperson is in. At the same time that the film questions the objectivity of the politically contested video image, it commands authority in its capturing of a complex profilmic now. Like Bazin’s description of a whale attack in Kon-Tiki (Heyerdahl, 1950), filming the overthrow of Nicolae Ceauçescu attests to the experience of revolution in its temporality as much as in the content of its images.58

The boundaries are shown for Europe in 1992. (Geographical Notes 2/3, 1992. Courtesy United States Department of State, Bureau of Intelligence and Research)

In addition, as a German film about East European events, Videograms forces an awareness of the border whose partial dismantling it narrates: the insider/outsider split between its (East) European participants and its (West) European directors. (In fact, there is another internal border here, because while Ujica lives in Germany, he was born in Romania. In Naficy’s terms, his filmmaking practice is exilic, accented.) In its attempt to engage visually with an Other, Farocki and Ujica’s film can be compared with feminist films such as Trinh T. Minh-ha’s Reassemblage (1982), in which Trinh speaks as a Vietnamese interlocutor of Senegal, and Chantal Akerman’s D’Est (1993), in which Akerman travels to the former Soviet Union. Here, though, a feminist and postcolonialist deconstruction of the documentary voice is mobilized to trouble the dominant binary of postwar Europe.

Videograms of a Revolution Those witnessing the Romanian revolution were in a dangerous position.

A film that makes even clearer the importance of itineraries, of charting subjective transnational routes, is Chico (Fekete, 2002), a German, Hungarian, Croatian, and Chilean coproduction. The protagonist is a national and ethnic mongrel, part Jewish, part Christian, with a heady mix of European and South American roots. Beginning in the 1960s, he takes part in political upheavals in Bolivia and Chile; travels to Europe; works as a spy, a soldier, and a journalist; and ends up in the 1990s fighting for Croatia in the Yugoslav wars. Chico’s narrative forms a picaresque itinerary, weaving through many wars and revolutions, but amid the chaos there is a persistent questioning of the relationships among spatial identities (nationality, ethnicity, language), histories (war, revolution, coup), and ideologies (from South American socialisms to European post-Communism). Chico points out that the changes in post-Wall Europe cannot be understood in a vacuum and that the ideological crisis of the Left touched on quite disparate geopolitical constituencies.

Czech art cinema is typically less engaged with the European Other: perhaps because of its strong national cinematic tradition, post-Wall Czech films have largely mobilized historical rather than transnational narratives as the space within which to imagine political change. Many of these films fit comfortably within the heritage genre, including Dark Blue World (Sverák, 2001) and Divided We Fall (Hrebejk, 2000). Distributed internationally as accessible and melodramatic Holocaust dramas, these films recount national histories in the wake of a political process of reimagining national identities, historical responsibilities, and ethics. A more ambiguous text is Buttoners (Zelenka, 1997), a portmanteau film that includes contemporary narratives, as well as a key story set during World War II. Unlike most heritage war narratives, however, this one takes place in a foreign country, Japan, and narrates the lucky escape of Kokura, slated as the target for the atomic bomb that was diverted to Hiroshima because of bad weather. The rest of the film consists of several small stories, interconnected in unexpected ways. The Japanese narrative returns when a group of girls at a séance raises the ghost of one of the American pilots, who wants to apologize for his actions in 1945.

Director Petr Zelenka is known for his absurdist style, and Buttoners can be read within a Czech aesthetic history of surrealism. The film’s coincidences of time, space, and characters suggest that geopolitics, like love, is arbitrarily determined. But, as with a previous generation of Czech surrealist films that includes Jan Svankmejer’s uncanny animations, the fantastical events in Buttoners entail a political logic.59 While arbitrary cruelties often refer obliquely in Czech cinema to the absurdities of life under state Communism, Buttoners suggests a new state of affairs: a lack of any social or ideological fixity, seen, for instance, in bizarrely humorous sexual perversity (the title characters remove upholstery buttons with false teeth). An integral part of this incoherent system is the haunting presence of the history of World War II. Here, the apparently arbitrary itinerary slips from Hiroshima to Prague and from sexuality to technology. The Other is not western Europe as much as Japan, America, and the altered place of Czechoslovakian history in the world system.

For northern Europe, the borders of East and West appear less pressing, but their effects are no less real. In Lukas Moodysson’s Lilya 4-ever (2002), made more than a decade after the end of the Soviet Union, new issues supersede the immediate fall-out of state Communism. Here, trafficking in women is the “social issue” addressed by the narrative. The film makes clear the connections among post-Soviet wild capitalism, west European economic dominance, and the exploitation of young women. Lilya is a teenager abandoned by her mother, when the mother runs off to the United States with her new boyfriend. Tempted by an offer to start a new life in Sweden, Lilya is kidnapped and forced into prostitution. On one level, the film operates a fairly direct extended metaphor in which Lilya is equally rejected by her mother and her motherland (a nameless post-Soviet republic), whose unregulated capitalism has left her father’s former workplace empty and its young generation kicking around in soulless housing projects. More important than this nameless state is Europe, and particularly the still-significant border of East and West, which Lilya traverses as an unwitting captive. It is the invisibility of this East/West border—its official nonexistence in the new Europe—that begets the invisible lives of women like Lilya.

Lilya 4-ever In an abandoned factory, postindustrial rubble frames Soviet history.

Lilya forms an intriguing case study of the different regional itineraries that post-Wall cinema can map. Like many contemporary Nordic films, it is concerned with transnational identities. But unlike the pan-Nordic space constructed by the various national funding bodies, Lilya emphasizes an exploitive rather than a cooperative north. Stylistically, too, the film makes awkward connections. Its working-class characters and relentless pessimism draw from British histories of social realism, while from Dogme it takes a digital video (DV) aesthetic and melodramatic narrative of an abused woman. But the film also includes religious fantasy sequences that sit less easily with these Western versions of realism. The difficulty with this itinerary can be seen in the problems that occurred when Sweden wanted to select the film as its Academy Award submission: since the film was mostly in a “foreign” language, it was originally judged ineligible. Russian-speaking Lilya could not represent Sweden. The academy relented, but this small controversy illustrates the film’s awkward location: in staging northern Europe’s implication in the European border, the film opens up new spaces of political and fantasmatic exchange.

Impossible Spaces

We may consider these border films as a point of emergence of the new Europe: as texts that can make clear the stakes in any developing politics and aesthetics of European-ness. Within this structure, arguably, the countries most radically transformed by these upheavals were Germany and the former Yugoslavia. While both Zentropa and Underground take as their primary historical object and location a single country—Zentropa is set in zoned Germany in 1945 and Underground mainly in Yugoslavia from 1941 to 1992—they do not work as the Italian romances do to tie nationally coded images to political histories but, instead, appear to visualize the space of the continent. And while these films are textually quite different, what connects them is a shared difficulty in conceptualizing spatial identities, both in terms of the nation and in terms of that nation’s relationship to Europe as a whole. Before addressing each film within its national context, then, it might be productive to consider what these locations have in common and why they provide such rich and troubling ground for a spatial and historical analysis.

The relationship of nation to Europe is a particular problem for any discursive figuration of Yugoslavia or Germany. Since the end of World War II, these countries60 have occupied unique places in regard to the Cold War geopolitical settlement: very different from each other, but comparable in that neither of them was fully locatable within the dominant taxonomy of Eastern and Western Europe. Germany was split into the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany, while Yugoslavia, by contrast, became a single, federal nation after the war, but in splitting from the Cominform in 1948 was removed from the Soviet sphere of influence and could no longer be considered simply a part of the Eastern bloc. Thus, both (all three) countries can be seen as signifying problems or limits for the logic of Eastern and Western Europe, and, indeed, Underground’s director, Kusturica, has said of his own European identity that “I was born at this extremely painful border between the East and the West.”61 The idea of the painful border is one shared by both Yugoslavia and Germany, and with the dissolution of these borders in 1989 to 1992 some of the most significant events in the formation of the new Europe were precipitated.

In Germany, the Wall became a new metonym of European change, this time indicating the collapse of Communism in its televised opening and rapid destruction. In 1990, reunification took place, and the nature of the new Germany’s inevitable strategic and economic dominance in Europe became a central subject of debate for the European Community, while within Germany the persistent cultural and economic gap between the former East and West rewrote Cold War geography as a new political problem. In Yugoslavia, the pressure on the spatial logic of the Cold War did not result in a unification but in a breaking apart. The secession of Slovenia from the Yugoslav federation in 1990 was the first step in what looked like a transition to Western-style democracy but proved to be a more complicated series of civil wars, in which the right-wing nationalism and territorial expansionism of Slobodan Milošević caused the bloody and drawn-out contestation of Serbia’s borders and thus of Yugoslavia’s various national spaces.62 In both cases, a spatial politics of borders and nationalisms is significant in the 1990s and in recent national histories.

These moments correspond to the time in which Zentropa and Underground were made—that of German reunification and of the wars in the former Yugoslavia—and to the historical moment in which the narratives begin. In other words, for both films, national and European spaces are both a historical and an ideological issue. Zentropa’s narrative takes place in 1945, suspended between the legacy of Nazism and the separation of Germany into East and West. While Nazism was an ideology predicated on the control and transformation of European space,63 the postwar structure installed by the Allies began with zoning and led directly to a de facto splitting of Germany’s national space into competing ideological blocs.64 Thus, both the Nazi guerrillas and the Allied occupiers depicted in the film are making explicit, and ideologically weighty, claims on European space.

Space plays no less a part in Yugoslav histories, and Underground begins in 1941, at the moment of inception of the national liberation struggle, when the prewar state was partitioned by the Nazis. However, even this moment is readable as “national” mainly from the point of view of Tito’s Communists and is contested by nationalisms in play in Serbia and Croatia during the 1940s, as well as the 1990s. As John B. Allcock points out, “No international frontier between the former Yugoslav federation and any of its neighbours is older than the end of the Balkan Wars (1911–13).”65 Allcock concludes that the problems of Yugoslavia “have to do in very large measure with the difficulty (perhaps one should say in relation to the Balkans, the impossibility) of mapping nationality onto territory.”66 The spatial problems of an extremely ethnically mixed population were crucial to the region well before World War II, but in both the 1940s and the 1990s their political implications became particularly acute.

That this spatial conflict should become legible in historical terms can be seen in the way the verb “to balkanize” has entered the English language, meaning “to divide an area into overly small states.” This linguistic example reveals the way in which history itself is a discursive problem for Yugoslavia. The negative tenor of the term “to balkanize” indicates the extent to which, at least in English-speaking countries, historical disposition has become the standard explanation for all events in the Balkans. The idea of balkanization is that the region can stand as exemplary of a kind of spatial logic consisting of pre-modern tribal hatreds, susceptible to endless belligerence and incapable of forming a modern multiethnic nation state. In this way, far-distant history is invoked to contextualize events: this happened during the 1990s war in Bosnia, which was frequently “explained” as a natural resurgence of ancient enmities. (This idea of a territory still caught up in its ancient feuds is similar to the discourse of the rural pre-modern south in Italy, although here it is used to more politically direct ends.) For this reason, any kind of history film on the subject of Yugoslavia will be overdetermined, as historical discourse itself is always already implicated in this primitivizing rhetoric.