REPRESENTATION, EXEMPLIFICATION, AND REFLEXIVITY

An Alternative Approach to the Symbolic Dimension of Cinematic Art

At this point we should speak of the symbolic function of any work of art, even the most realist.

—Jean-Paul Sartre

WITH FAR MORE CREATIVE AND EXPRESSIVE POTENTIAL THAN communication via conventional signs and codes, although also incorporating these, we have seen that filmmaking may be aptly described as a form of symbolic world-making. It entails the use of preexisting materials of many kinds organized and synthesized in novel, artistic ways in the interest of creating new meaning relations. The resulting structures prompt both the materials in question and the natural and human realities to which they are attached to be seen and thought of differently, as a result of the contextual displacements typical of world-making. But if these creative processes in cinema and other arts (including those Goodman identifies) are variable and overlapping, the modes of symbolic reference that make up their content are more clearly independent of each other. The acceptance of a basic multiplicity of symbolic forms, functions, and objects of reference, beyond what is encompassed in other theories of the film sign, is key. Just as we have found that the macroprocesses of world construction help us to better understand the sorts of transformations marking artistic filmmaking practice, so we can now explore, in somewhat closer detail, how certain well-known features of films with artistic aspirations and merit make use of fundamentally different forms of pictorial and verbal reference.

CINEMATIC REPRESENTATION AS DENOTATION

Goodman’s art-as-world-making thesis, concerning how systems of symbols in cultural praxis constitute the cores of worlds (or world-versions), builds on the “general theory of symbols” and their functions, as first laid out in his earlier Languages of Art.1 This influential study centers on the nature of symbolic reference itself, both within and without the practices of art. Tied to his philosophical nominalism and an “extensional” view of reference and meaning (indebted to the views of W. V. Quine), Goodman argues that the most common type of reference made by visual representations is a matter of denotation. The idea that denotation is the “core of representation”2 clearly returns us to the diegetic concept of a denoted aspect or level of a film constituting the basic world-in a cinematic work in the form of a representational and fictional narrative-supporting construct (see chapter 1).

To denote, in the first instance, is to name or fix a relation, otherwise “arbitrary,” between a symbol and an item in empirical experience. This process may involve no more than the attachment of a label that, in this minimal sense, serves to pick out and identify the item—for example, when we attach the label “Napoleon” to certain pictures. Conceived in terms of pictorial reference-making, then, representation may extend, as it does in narrative films, to fictional characters, situations, places, and entire worlds that have no literal, embodied existence. As we saw in chapter 1, denotation, and what Goodman terms predication, in narrative films is both literal and fictive (or figurative). Thus an image (in the form of a medium-close shot) of a figure leaning against a bar counter in Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas denotes in multiple literal and fictive ways simultaneously: as an image of a person, of a woman, of an actress (Nastassja Kinski), of a fictional character (Jane, as the object of the protagonist’s quest), of that character at a certain space and time within the fictional represented world and story of the film, and so on. For Goodman, however, basic visual representation, or “depiction”—including the use and interpretation of photographs—is seen to operate largely apart from natural, perceptual resemblance between image and object in the world and instead through conventional, culturally informed attribution. This view runs counter to Metz’s understanding of denotation in cinema as almost exclusively a matter of visual resemblance or natural “analogy,” with the photographic basis of traditional film images ensuring that they are first and foremost iconic of their referents.3

The general problem of the extent to which the basic representational aspect of visual images is a cultural acquisition or an innate capability of the human mind is a familiar topic in the contemporary philosophy of art. The consequences for film theory of adopting one or the other of these supposed “perceptualist” and “conventionalist” alternatives concerning how the film medium and aspects of film viewing experience should be conceived has also been the subject of a great deal of attention among theorists and philosophers.4 Anchored in the observation that in some system of representation literally anything may “stand for” almost anything else,5 Goodman’s now famous, strongly conventionalist position that visual resemblance is not only not a sufficient condition but is not even a necessary one for successful pictorial representation (i.e., recognition) is a counterintuitive one. It is both literally and figuratively “iconoclastic.” The substance of the many criticisms that have been leveled against it is the claim that iconicity (the visual resemblance between signifier and signified) simply must be admitted to play at least some more prominent if not, strictly speaking, necessary role in pictorial representation. It seems highly plausible that there are, in fact, so-called perceptual constraints at work throughout visual communication. And, depending on how it is specifically interpreted,6 Goodman’s conventionalism concerning our most basic comprehension of pictures may appear far too strong. However, making more room for resemblance with respect to literal representation (or denotation) in visual art and, more pertinently, cinema does not (as Metz also recognizes) obviate the symbolic character of the relation.

Jenefer Robinson, Dominic McIver Lopes, and Dudley Andrew (with reference to cinematic representation, specifically) are among the philosophers and theorists who have justly recognized that the chief merit of Goodman’s provocative account of the symbol function of denotation is properly acknowledging that no matter how they are generated, pictures, like linguistic expressions, must often not only be viewed but understood for both what they are and contain as symbols.7 Mitry writes that a film “absolves us of the need to imagine what it shows us, but . . . requires us to imagine with what it shows us through the associations which it determines.” This ensures that in cinema the image is both a perceptual “window” and a cognitive “frame.”8 Indeed, the presumed opposition between taking film images to be iconic of their referents (and more or less fully accessible to anyone with normal vision), or as having semantic contents that are preassigned by means of culturally specific, informally adopted codes that film viewers must in some manner learn and master, is a false or, at most, a dialectical one, quite susceptible to a synthetic resolution. Neither so-called seeing-theory nor sign-theory is a truly self-sufficient alternative in any more complete (and less predisposed) account of film viewing communication.9

Further, and more germane to our central concerns, many of the most significant aspects of films as works of art are simply not explicable in terms of the most literal representational or denotative function of the film image, no matter how this is theorized—that is, whether in perceptualist (and naturalist) or conventionalist (cultural-semiotic) frameworks. The conditions and capacities associated with our successful recognition of the contents of pictures in the ordinary, pragmatic contexts of their communicative uses are, in and of themselves, still below the threshold level of an aesthetic apprehension and appreciation, at least in the majority of cases involving artworks (including photographic ones) and our encounters with them. On this basis, regardless of how conceptually sophisticated or flexible it may be, no general theory of basic pictorial representation or recognition (nor, it should be added, of meaning and emotion as tied to it exclusively) applied to cinema will be able to adequately account for a film’s artistic or aesthetic dimensions. Modifying Goodman’s formulation (seen as supported by the existence of nonrepresentational art) that denotation is neither “necessary nor sufficient for art” in general, and following Mitry, in the great majority of narrative cinematic art (as representational), denotation would appear necessary but still far from sufficient.10 For this reason, among others, in defining and understanding a film as an artwork, as distinct from a focus of inquiry limited to the narrative dimension and its construction, we must move beyond “mere” denotative representation as rooted in the iconic and indexical properties of film images (as well as contemporary theories of depiction that are perforce limited to what amounts only to literal denotation) and instead consider other forms of meaning relations.

Returning to Goodman’s cognitive aesthetics: as has also been recognized by other philosophers, his treatment of visual denotation as largely if not entirely conventional, and its attendant difficulties, does not threaten the substantial insight and value of his identification and descriptions of the other major forms of symbolization present and in play in artworks defined in contrast to literal representation.11 Nor does it work against their multifaceted, and largely uncommented upon, relevance to cinema, as will be my principal focus of interest in the first half of this chapter. Such nondenotational forms of reference may likewise be seen to constitute a great deal of a film’s characteristically aesthetic “content” and meaning, as closely bound with and often articulated through its cinematic and artistic presentation, and “form” in this sense.

ARTWORKS AND EXEMPLIFICATION

Developed by Goodman and his occasional coauthor Catherine Z. Elgin, the concept of exemplification is a major and original contribution to the analysis of presentational symbolism and, a fortiori, to the theorization of cinematic art. Its importance lies primarily in its acknowledgment that a symbol—and an artwork (as an object made up of symbols)—may, and often does, refer to extrawork realities by referring to itself. Binding together a work’s perceptual properties and the interpretative discourses that assign them meanings, exemplification provides a highly productive way of thinking about those qualities of sensory presence and alterity, self-reference and self-definition, central to the heterocosmic view of art worlds while also squarely situating them in relation to the extrawork (and “real world”) realities and processes of signification that give them transsubjective meaning.

The key notion of exemplification is defined as “possession plus reference,” and Goodman illustrates it by pointing to the function of samples in everyday life and commerce.12 A paint sample (or “chip”) consisting of paint on a piece of cardboard functions as a sample of a type and color of paint by drawing attention to some of its properties as an object (the precisely shown color, shine, and texture of the paint on the surface) but not others (e.g., the size, shape, thickness of the cardboard, or the chemical composition of the paint).13 The same is true of a tailor’s cloth swatch, where some properties (thickness, pattern, texture, weave, type of material) and not others count as relevant for its purpose and use as a sample.14 These sorts of things are, of course, symbols. But unlike others (e.g., the vast majority of spoken or written words and pictures that make reference) they actually possess at least some of the properties to which they also refer. While the denotational symbol, including a pictorial one, is founded on an absence, pointing elsewhere to some real or imaginary object(s) to the extent that it may become virtually transparent to that which it refers, the symbol in exemplification is never a so-called arbitrary (or mobile), or transparent, one. Instead, it admits and calls attention to its own sensory presence, freely displaying some of its own properties so that it may also signify the same or similar properties to be found in experience apart from, or outside of, it—for example, the property of “squareness” as exemplified in Joseph Albers’s pioneering abstract paintings. This clearly contrasts with common linguistic reference and differs, as well, from denotation or depiction (as the general form of identifying reference by means of pictures), wherein the object portrayed in the picture is not possessed by it as an object (or, at least, not in the same way).

From a particular analytical standpoint the concept of exemplification can be seen to address the fundamental duality or ambivalence of the representational artwork qua symbol. It both draws attention to itself, as a physical, incarnate, and sensory object, and participates in a cognitive-reference relation or function, pointing to something it shares with any number of other real (or, perhaps, fictional) objects or beings. Indeed, in this major aspect there seems to be a clear connection between the exemplification relation Goodman assumes and Cassirer’s seminal thesis concerning the “symbolic form” of art, the exemplars of which are characterized by self-representation as well as extrinsic representation. Of course, properties of artworks, including films, do not behave in the clearly planned, determined, and well-ordered manner of those of commercial samples. They are seldom easy to discriminate individually, and they comingle and cooperate, in the sense of highlighting or foregrounding perceptual aspects of one another in a holistic fashion. Nor, crucially, and as Goodman maintains, are exemplifications in art confined only to intrinsic, sensory qualities of works as the target object of self-reference.

Exemplification always involves recognition of the presence of a general property or quality (of things) brought to reflective attention by some object of direct perception. Yves Klein’s paintings exemplify “blueness” in general (with all of its potential natural, psychological, and cultural-symbolic associations) through the artistic employment of a very specific (in fact, artist-created) shade of blue paint. In this instance the exemplifying feature (the paint on the canvas and its color) and that to which it refers (blueness) are very closely related (almost identical)—hence they stand in a more “literal” relation, in Goodman’s terms. However, through its equally sensory features a Jackson Pollock painting may exemplify temporal rhythm, or a Caspar David Friedrich painting may elicit properties such as holiness or tranquility. In such cases as these there is a (much) greater “metaphorical” distance (as Goodman suggests) between the exemplifying features (e.g., circular patterns of paint advancing across a rectangular canvas; a painted landscape and the way that it is composed, colored; etc.) and the quality or idea to which these works refer and act as individual “samples.” This is because, of course, unlike being blue, temporal rhythm is not the sort of property actually (objectively) possessed by paintings as perceptual objects (alone), whereas it is so possessed by musical compositions, for instance. Such more mediated, figurative distance between the features of works accessible to our senses and that which we are able to interpret them as exemplifying is even more pronounced with respect to artistic exemplifications of “holiness” or “tranquility” or “anxiety,” which are, obviously, states or qualities more literally belonging to (and associated at times with) people, or, in some cases, perhaps, non-artistic objects and places in their anthropomorphic aspects.

While denotation generally aims at reference that is empirically determinate (i.e., we don’t use the word dog to identify a passing cat), exemplifying symbols are generally more “open,” or indeterminate, considered as tools of reference-making (and therefore more demanding of interpretation). At the same time, however, the exemplifying symbol is individual and nonarbitrary, maintaining a connection between at least some of its own intrinsic properties and those of the object of reference. And it is this aspect of the relation that fosters the more concrete and “particularizing” modes of representation (the so-called concrete universal) that we associate with much of representational art.

Goodman argues that the symbolic function of exemplification—which is found in both abstract and representational art (where it often works in conjunction with literal representation)—is a characteristically aesthetic one, since it is the source of much of a work’s cognitive interest and stylistic import. How, what, and whether any given work exemplifies is a frequent, underlying subject of artistic interpretation and debate. Indeed, the fact that what properties an artwork is seen to exemplify “vary widely with context and circumstance”—historical, cultural, individual—is acknowledged in Goodman’s suggestion that in relation to a number of issues the question of “what is art?” should be replaced by “when is art?”15

Moreover, and as we can add to Goodman’s and Elgin’s account, the relative presence of exemplification can help to distinguish between more and less artistic uses of any medium, including film in its celluloid or video-digital forms Along with obviously lacking fictional denotation, most industrial films, home movies, historical recordings, and many (although certainly not all) documentaries feature far less in the way of concentrated, complex, and self-conscious exemplification than many narrative films, and certainly less than, e.g., The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, On the Waterfront, The Conformist, and other canonical cinematic works. Thus, the thesis of “possession plus reference” may be seen as one alternative, and relatively more precise, means of distinguishing between artistic and nonartistic uses of cinema, in referential terms. The presence and relative amount of exemplification is certainly a more useful yardstick in this respect than Metz’s appeal to a “wealth of connotations” as constituting the difference between a “medical documentary”—as almost entirely rooted in literal, visual denotation and one predominant type and level of meaning—and a “Visconti film,” in the French theorist’s memorable example.16

Since, to repeat, in exemplification only some of the properties of any familiar sample or model participate in the task of reference, there is an intention-governed selection of those properties on the part of the maker or designer that is necessary for, and precedes (in the logical sense), the sample’s or model’s ability to function as such.17 The same is true of the more sophisticated exemplifying symbol in art. However, just having the relevant perceptual properties to which a meaning is conjoined is not enough, since the symbol, and work (in this case) must in some way “show them off,” as Goodman writes,18 or “highlight” them, as the noted analytic philosopher Bas C. Van Fraassen suggests in support of this widely applicable understanding of the workings of some symbols in the arts and sciences.19 In other words, in exemplifying, the object as symbol must somehow foreground the specific properties of itself that it wishes to put to external, referential use. Thus, “the properties that count in a purist painting are those that the picture makes manifest, selects, focuses upon, exhibits, heightens in our consciousness—those that it shows forth—in short, those properties that it does not merely possess but exemplifies, stands as a sample of.”20 These are just the properties that in most cases (at least) the artist consciously intends to call to the attention of his or her audience, as somehow relatively more pertinent or revealing of the subject than others, and which are also at the forefront of the work’s aesthetic experience and interpretation.

In the process of exemplification the self-highlighted perceptual aspects of a sensible symbol are abstracted away or, in Goodman’s terms, “projected” out from it.21 They are attached (by its interpreters) to relevant “predicates” (labels), or apt descriptions, within any given cognitive, historical, cultural, and artistic formation, in the processes of the work’s understanding and critical interpretation.22 This is not only a question of a signifying or semantic function on the part of visual art, for instance, but of a concrete, visually demonstrative one. In practice, the grasping of an artistic exemplification, which “actualizes” it, is typically the result of a recognition on the part of audiences that possess the requisite degree of acquired cognitive (and cultural) background and sensitivity to interpret perceptual features in certain ways. Through exemplification (in this view) works refer us not only to specific real or fictional objects of denotation (basic representation), wherein a certain and unequivocal specificity and concreteness in reference-making is the desired end. But they also refer to more abstract and general concepts (including that of “art” itself, in some instances), together with sensory and human qualities.23 In effect, exemplification is largely a matter of the ways in which, through their concrete and sensory forms (even, that is, when their exemplifying features are representational), artworks actively and often intentionally invite the linguistic descriptions that constitute what we take to be our understanding of them, and the full semantic or thematic appreciation of what they have to “say to us,” through self-pointing or highlighting.24

One reason that the conception of reference plus possession, or possession plus reference, is so germane to art is its insistence on the fact that some meaning content is physically or perceptually embodied in a singular created form, as opposed to the generic product of the fixed structures of discourse. Monroe C. Beardsley, Margolis, and Carroll, among others, have argued that the properties that artworks may be thought to exemplify are most often not those for which we have labels and descriptions ready at hand, in marked contrast to denoted objects of representation. Although these philosophers cast this as a potential weakness of Goodman’s concept as applied to art, it is instead a reflection of the fact that rather than embracing only permanently fixed properties of works, exemplification is above all a contextual relation involving actual, historically situated and intending artists and their audiences, participating in relevant common traditions and interpretation that produces novel recognitions about works and about the worlds (or worlds) with which they are concerned.

CINEMA AS AN EXEMPLIFYING ART

Symbolic exemplification appears central to the worlds of film works of art as created, experienced, and interpreted. Indeed, cinema in its artistic uses may be seen as even more deeply rooted in different forms of exemplification than other arts, through such selective self-highlighting of literally and “metaphorically” work-possessed properties of different types. The particular sort of relations between literal representation and figurative meaning common in films, which we have already discussed, is key here.

As we have seen to this point, in their medium-given and -recognized perceptual facticity and concreteness, as bearing an “analogical” relation to reality, film images (and sequences) are a powerful vehicle for new artistic significance as rooted in figurative, associational meanings still (very) closely tied to perceptual features. As Mitry’s arguments may be taken to lend persuasive support to, given their (often recognized) status as elements of the global perceptual-symbolic and artistic presentation that we posit as the world-of a film, artistic exemplifications may stand out for attention to a greater degree in cinema than other arts. This is by virtue of the marked contrast between basic cinematic denotation—as concrete, seemingly “natural” or “given,” often powerfully iconic, and constitutive of the fictional-represented world-in—and the extranarrative symbolization (exemplification), which, while copresent with denotation, transcends and stands out from it and the represented, diegetic world. Beyond this fundamental dynamic, which reflects a duality at the “ontological” heart of a cinematic work of art as literally representational and fictional-narrative, but also, and equally, figuratively and artistically significant and expressive, there are other reasons why cinema may be considered an art of exemplification as much as an art of reality.25 These are related to factors well within the intentional, creative control of filmmakers.

Films are able to adopt a wide variety of sensory and cognitive modes and registers of address in aid of artistic exemplification. In comparison with other forms, there are simply more and different means—an entire arsenal—at a filmmaker’s disposal for the aforementioned “self-highlighting” of artistic features (or of features as artistically significant, to be more precise) in the minds and attention of viewers as a way of constructing and conveying specific ideas and expressions. Such significance may be articulated through the camera’s “intentional” view and movement, entirely apart from, or in dialectical relation with, that of actors and characters, for instance. As not only audiovisual but temporal and sequential, films can also dwell on certain of their constructed images and sounds, thus “showing them off” for aesthetic consideration, together with whatever they (may also) literally or figuratively represent. And, of course, through editing, films may also return to and repeat these for artistic emphasis. As we have seen, the function of exemplification ensures that the full experience and interpretation of art is never free from linguistic description and interpretation but must work in and through it. In the case of cinema, however, language, with all of its potential for emphasis, self-description, and self-characterization, may be literally present in the form of voice-over, intertitles, filmed text, and so on. As Godard’s films have shown over more than a fifty-year period, this may add immeasurably to cinematic exemplification as a means of conveying meaning and feeling that fuses, intersects, or counterpoints both image (i.e., literal cinematic representation) and story (fictional narrative and drama).

Cinematography, camera placement and movement, editing, staging, design, music, and lighting may all be seen to take up what amounts to a particular perspective upon the represented world-in of some films—which is, of course, for films to draw attention to (exemplify) some aspect of themselves as created and intended works and, thus, to generate extranarrative (and extradiegetic) referential meaning via the intentions of the filmmaker(s). Moreover, and as I have already discussed, as channeled through the specific formal and technical means of cinema, the transart world-making techniques of weighting (which, as a matter of emphasizing and highlighting perceptual features, is particularly close to exemplification in Goodman’s account), ordering, composing/decomposing, filtering, deleting, framing, and so on, transform quotidian realities and create new or less-familiar ones. Yet they may simultaneously serve to emphasize, foreground, comment on, and draw attention to certain possessed properties of films in their functioning as artworks (not least these very processes) for viewers attentive to them. Even if not all films and filmmakers take full advantage of them to pursue the communication of meanings and affective-emotional contents beyond basic story contents—and do so in creatively original and experience-illuminating ways—there are seemingly far more individual means of such self-highlighting of features on the part of films afforded to creative filmmakers than to artists working in other media.

Finally, cinema affords many different channels, in fact far more than any other art form, for “(self-)reflexivity,” which has rightly been seen as a major aspect of many artistically valuable films and cinematic styles. Reflexivity may convincingly be seen as but one rather specialized form of artistic exemplification. Like allusion, or the exemplification of formal properties (soon to be discussed), reflexivity as a feature of style is one more (optional) tool or instrument, albeit a very efficient and sometimes more direct one, employed by a cinematic work to exemplify certain of its own perceived features in order to convey (or better convey) certain thematic, conceptual, and expressive contents and meanings. In line with how reflexivity in film and other arts is generally defined, however, in this case such exemplified meanings (objects of reference) invariably pertain to cinema itself, of which every film is a particular example (or a single “sample”).

In more conventional narrative cinema, for instance, important artistic exemplification (in any of its basic forms) may be relatively more accessible, recognized, or prominent, given that nonliteral and nondenotative symbolization tends to take rather more obvious and direct forms. Yet this is not always the case, and it is unwise to generalize in this respect or to suppose that familiar film-studies classifications such as “mainstream,” “Hollywood-style,” “popular,” “art house,” and so on can always be supported here, given the great plurality and diversity of narrative cinematic art and the intentions of film-world creators.

In sum, through various forms of exemplification that we will now consider in greater detail, a film world is constantly kept in motion, and transports the viewer along with it, in two directions. Sometimes alternating, but sometimes virtually in the same instant, it figuratively expands outward to make contact at many points with other, larger realities, and the symbols, signs, and objects of reference they involve, yet it also contracts inward, to reflect on its own specially created virtual and artistic reality, its own cinematic work-world.

FORMS OF EXEMPLIFICATION IN CINEMA

Literal exemplification, which Goodman describes as involving what are commonly thought of as the “formal” aspects of works, is as prominent in cinema as it is in painting and other static arts of vision (as his main examples). Like abstract, experimental films (where denotation is either relatively minimal or virtually lacking altogether) narrative films may draw special attention to features of light, shadow, color, composition, rhythm, and movement, which thus come to possess a meaning (or an additional meaning), whether thematic, psychological, metaphorical, reflexive, or allusive. A film’s being in CinemaScope (or another widescreen format) is a formal-medial property of it as a created whole, the result of a choice preceding its shooting. In films such as Frank Tashlin’s The Girl Can’t Help It, Godard’s Le mépris and Tout va bien, and Nicolas Ray’s Bigger Than Life (whose title may also be seen as exemplificational in this respect), the format and its effects are also artistically foregrounded, drawing viewer attention to the compositional frame as possessing a number of possible meanings and associations relating to the narratives, themes, and styles of these films. Likewise, a film’s relative lack of close-ups may become a highlighted symbolic-aesthetic property of it when a sudden close-up at a significant moment underscores (for some interpreted purpose) the general absence of such framing. Rather than such formal features and techniques carrying an artistic exemplification of some idea, quality, or feeling in themselves, this is instead a matter of how these are seen (or heard) and interpreted, within the context of a film and its world as a whole (and within the context of cinematic and artistic traditions), and given the expectations and memories of viewers.

In Goodman’s original view, and as I have already discussed, the possession of exemplified properties need not be literal and physical, or more directly sensible, but may instead be metaphorical.26 It is recognized that artworks have meaningful features that they do not actually possess as materially instantiated and that their higher-order or imputed properties are not reducible to merely perceptually presented constituents. Thus a Van Gogh painting can exhibit, draw its beholder’s attention to, both color, which it literally has, and madness or love or some other attitude or emotion, which, not having the animate capacity to feel, it “possesses” only metaphorically as a visually accessible but not sensory property.27 Similarly, a film may literally exemplify a particular color or color scheme (e.g., as in Kieslowski’s Three Colors: White and Jarman’s aforementioned Blue), or quick cutting, or the play of light and shadow, or medium-close shots—all of which are empirical properties films possess as either physical objects or perceptual experiences alone. Yet a film may also exemplify melancholy, voyeurism, the concept of justice, Plato’s allegory of the cave, or any other anthropomorphic and abstract realities “only” figuratively. The same holds true for any sensory qualities (including those involving touch or texture, referred to as “haptic,” or those theorized with reference to synesthesia) that cinematic works foreground but that, while literal and physical in noncinematic experience, are possessed by films in a nonliteral (nonactual) fashion only. As is characteristic of a great deal of symbolization in art, however, even when such reference is nonliteral in this specific sense, it still operates through, rather than bypasses, particular perceptual features of films, features that are foregrounded for attention through all the means at the film artist’s disposal, with this thus qualifying as exemplification.

Some critics of the concept of exemplification and its suggested role in art have focused on the expression of feeling and emotion it is seen to encompass. They have viewed it as an overly cognitive attempt to bind all expressive content to pale and abstract reference relations. Goodman himself candidly admits that this view may well “invite hot denunciation for cold over-intellectualization” of aesthetic experience.28 Certainly this concept appears insufficient to account for all (and perhaps even most) of a film’s affect and emotion, as instead stemming from more immediate and relatively unreflective recognition of an image’s contents, or more direct sensory affects of formal features, some of which may have an artistic significance in films (as will be considered in the next chapter). It does also appear, however, that there is a class of aesthetically relevant feeling contents in cinema, the instances of which, like certain qualities or concepts, are conveyed through self-reference, entailing conscious attention to films as intentionally constructed objects and artistic experiences. Here it may be simply noted that in artistic uses of any medium, feeling and emotion may be as much an “idea” articulated and intellectually grasped from an affective distance, as it were, as something more directly communicated and actually felt by audience members. More generally, as Goodman observes quite correctly, “Emotion and feeling . . . function cognitively in aesthetic and much other experience.”29 Citing this point specifically, Kristin Thompson has stressed the importance to film theory of Goodman’s view that to be engaged with any artwork is to be involved with it “on the levels of perception, emotion, and cognition, all of which are inextricably bound up together.”30 While keeping in mind that a film’s reference to formal properties, external cultural realities, and abstract themes and concepts may all carry an affective charge, I wish to focus on exemplification as centered on these rather than on the expression of feeling per se.

Since we are attempting to address the total symbolic structure of cinematic works and worlds, even if only in schematic fashion, following on from noting the presence of “metaphorical exemplification” in cinema, it should be mentioned that metaphor itself (also including metonym and synecdoche) is a well-known and studied feature of many films, associated with artistic practices of many of the most renowned filmmakers.31 In cinema, as Goodman argues is true of artworks generally,32 metaphorical expression may be seen to cut across symbol functions. Metaphors may be generated by denotations or exemplified properties, either through literal reference also to be taken figuratively or through additional levels of apt descriptions or interpretations, which certain properties of cinematic images and sounds invite viewers to entertain and apply. While literal representation in films most often crosses into the territory of metaphor by means of semantic conventions—that is, in the vision-based evocation of preestablished metaphors of common speech or literature—the relation of exemplification is of much more potential artistic relevance and interest. Here, by contributing to the making of novel associations and showing up heretofore unrecognized relationships among things, events, and character actions—most often in terms of the sharing of properties among screen-depicted phenomena—film metaphors connect up with the world-making processes described in the preceding chapter, including, for instance, visual deletion as related to metonym and ordering as related to synecdoche.33

Together with literal (or “formal”) and metaphorical exemplification, another significant form of symbolization that involves directed self-highlighting on the part of artworks is based on difference and absence. Goodman refers to this as “contrastive exemplification.”34 It is tantamount to a reference by an artwork of something interesting about what it does not literally possess as this is highlighted in some fashion by what it does. As Lopes suggests, in discussing the importance of the concept, this form of exemplification is at work in artistic versions and variations (of other works) of all kinds, given that “variations represent their antecedents by means of differences in content, not just shared contents.”35

Contrastive exemplification in cinema does not apply only to remakes and different film versions of the same stories, subjects, and events, however, but also to less direct relations among films qua films, or any extrawork realities signified by a conspicuous absence and difference. For example, to the cinema-literate viewer a great deal of the power and interest of Sokurov’s Russian Ark’s revolutionary form—composed entirely of a single, continuous ninety-six-minute long shot achieved through the use of a digital video camera—is its exemplification by contrast and omission of the narrative, formal, and affective roles of editing in films, precisely by virtue of notably lacking it. Moreover, this patent absence has a specific historical, cultural, and stylistic significance. Given the centrality of the editing process and of different theories and practices of montage in “official” early Soviet cinema (e.g., the films of Eisenstein and Pudovkin)—together with the fact that Russian Ark, entirely set in the Hermitage museum, is concerned with centuries of Czarist-Soviet history—the film’s dramatic renouncement of editing is a provocative and reflexive instance of an exemplified feature of a film’s presentational form being in complex, internal dialogue with its subject, theme, and setting. Thus this contrastive exemplification is not simply one of many figuratively referential aspects of the film but serves to significantly define its style and meaning as a work-world.

A final major form or species of exemplification is allusion, which is symbolically “indirect,” in the sense of being a matter of “possession plus reference” at a (larger) series of removes.36 As such, it is a principal way in which works become linked and connected to other works (and world-versions) and thus cohere into larger established categories such as genres, movements, and traditions. Here again cinema’s hybrid and composite (and, as Langer says, “omnivorous”) character provides it with a seemingly limitless allusive capacity, able to range at will into “higher” and “lower” realms of common cultural experience.37 If each film constructs its own world, then allusion to other films, and other works and forms of art, is a way of building bridges among these, allowing our thoughts and feelings to pass from one to another and back again.

Although not strictly necessary for this form of reference, and methodologically deemphasized by Goodman, the actual intentions behind the vast majority of artistic exemplifications distinguish this concept of allusion—and its present application to films and their worlds—from various influential theories of “intertextuality.”38 What Goodman and Elgin (separately and together) theorize as indirect exemplification also transcends what allusion is often seen by literary and film theorists to involve—namely, express or implied references to the represented contents of (other) works of cinema, art, literature, and myth. Instead, it pertains to associations that a work prompts with potentially any extrawork reality that is less directly present within the interpreted structure of a work-world, including historical facts, philosophical or scientific concepts, and knowledge concerning creators or performers.

Clearly, allusion may be a major part of a narrative film’s aesthetic experience and artistic structure and intentions. Recognition of such reference often requires relatively more specialized or sophisticated background knowledge on the part of audiences. As Goodman aptly remarks: “representation, [more direct] exemplification, and expression are elementary varieties of symbolization,” but as indirect exemplification, allusion “to abstruse or more complicated ideas sometimes runs along more devious paths, along homogeneous or heterogeneous chains of elementary referential links.”39 In describing the sorts of complex interactions between symbolic functions that take on aesthetic significance in film worlds, we will shortly look at some examples of such “devious paths” of association-making in cinema.

REFLEXIVITY AS SYMBOLIC-AESTHETIC EXEMPLIFICATION

Recognition of the importance of the exemplification relation in art helps to lay the groundwork for a new, and much needed, alternative model of (self-)reflexivity, which, although a ubiquitous term and concept in film theory and criticism, is still relatively underexamined, at least in systematic terms. Apart from the way in which all artistic exemplification is a matter of self-reference on the part of artworks (to their significant aesthetic features) and is thus akin to self-reflexivity in this general sense, it may be considered a specific type of reflexivity. Indeed, conceiving of this feature of many film works and worlds as a version of exemplification (one that is literal and metaphorical simultaneously, as it were) avoids some of the difficulties inherent in existing accounts of (self-)reflexivity in film theory, as these are closely bound to the theorization of modernism, postmodernism, and some “Brechtian theses” (to cite a relevant, well-known article by Colin MacCabe), as well as other frameworks.40 More positively, this connection with symbolic exemplification may also be seen to further unify, and add conceptual support to, a number of perceptive observations on reflexivity in cinema now scattered about in a number of writings by well-known film theorists and critics.41

Remaining, for the moment, with Goodman, in his and Elgin’s later development of the idea of artistic exemplification, and without discussing reflexivity under this name, mention is made of the way that some characteristically modernist buildings (we may think of Paris’s Centre Pompidou) intentionally exhibit their functional “structure”—girders, pipes, ventilation ducts, elevators, and so forth. Not only do they make these visible, but the buildings in question call attention to these practical features, which thereby come to possess an aesthetic significance as part of a particular architectural vision and program.42 This is in obvious contrast to concealing such practical and structural features, as many older architectural conventions and styles would dictate. Allowing for relevant, major differences among the media, this general practice may be considered roughly analogous to one major form of cinematic reflexivity involving a film’s highlighting aspects of its “structure” as a film, in spatiotemporal, formal, or narrative terms (as was briefly touched upon in the previous chapter, in relation to the world-making process of ordering).

For example, a familiar form of such reflexive exemplification as involving narrative structure pivots on the specific relation between the world-in and the world-of a film. Memorably present in Psycho, and, more recently, The Prestige and The Skin I Live In, it entails a particularly surprising turn of events that serves to cast all that came before it in a film in a new and emphatic light. Conspicuous attention is thus drawn by the film not only to what story information has been presented to, and withheld from, the viewer (and often characters) and when but also how this was actually accomplished (by the film and its creators) in specific formal-stylistic and storytelling terms, and its broader artistic meaning. This, in turn, may well prompt reflection on the artistic ends and possibilities of different, or alternative, narrative structures within cinema, more generally. In contrast, some of the films I have previously cited in relation to different means of ordering as a world-making process—e.g., Vivre sa vie, with its twelve titled episodes, or tableaux, as its main subtitle immediately announces (thus drawing further attention to this particular presentation)—also clearly illustrate an overt exhibition of cinematic structure, in this case formal or presentational structure, as relatively independent of story and plot.

Apart from narrative or formal structure, per se, reflexive exemplification in cinema has many other vehicles and objects, including simultaneous reference and self-reference to subject matter, other films, particular cinematic techniques, and aspects of dramatic performance and character—all of which, as present and recognized in films, may prompt focused reflection on cinema’s history, technology, and processes of filmmaking and film viewing, on the part of viewers. Its target objects of reference may, for that matter, entail all of these together, as in “uber-reflexive” films like Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom and Lynch’s Inland Empire.

Here it is helpful to recall that in contrast to denotation, which moves from “symbol to what it applies to [i.e., some empirical object] as a label,” exemplification is an opposite movement in thought from the concrete (here, artistic) object functioning as a symbol to “certain labels that apply to it or to properties possessed by it.”43 Put differently, the basic cognitive relation remains one of reference-making, but it starts out with a perceptual object functioning as a symbol and ends with a proposed linguistic (in this context, film critical and stylistic) description of certain of its features. Thus, to take a fairly basic example, the image of a film camera pointing out toward the viewer at the beginning of Godard’s Le mépris (operated by Raoul Coutard, the film’s cinematographer) or at the ending of Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (operated by Wexler himself, as both cinematographer and director) literally represents (or denotes) in both cases a familiar object—a film camera. Yet, in ways that relate to their narrative action and main themes in provocative fashion, these images simultaneously figuratively exemplify each film’s status as dependent upon a camera as not only an impartial and objective tool of representation but an inescapably subjective means of mediating, interpreting, and organizing experience and of turning familiar reality into an “alternative” world. In the case of Le mépris, as an additional, or combined reflexive exemplification, Godard’s opening voice-over, with which the image of the camera and its lens is paired, opines that cinema may “substitute for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desires.” He also states that Le mépris is the “story of that world.” In other words, and as characteristic of artistic exemplification’s typical movement from the particular to the general (and back again), it is a story that on one level is “about” all cinematic world-creation as much as “about” Le mépris’s specific, fictional reality, as the representational and narrative vehicle in and through which the more general subject, or idea, is addressed.

When, in the course of viewing and in subsequent interpretation, critics, theorists, and other knowledgeable viewers attach such labels and descriptions as “self-reflexive,” “self-aware,” “auto-critique,” “Brechtian,” “acknowledgment of the viewer,” and so on, to the above-noted images and sequences (and many others like them), they are not, of course, describing only what those elements refer to (denote) literally but what they, and the work, evoke and elicit by symbolic association. In this case, the camera (and its image) is transformed from the particular to the general, as its own idea; it is no longer a single piece of equipment but is (in these contexts) the necessary transformative instrument of all filmic creation, including the film in which it appears. Here I must reiterate that the labeling and describing at work is never “merely” descriptive, since the meaning(s) of film images, sequences, and works are experienced and understood in certain ways (and not others) as a direct result of such attributions.

From this perspective, then, (self-)reflexivity must be understood as a specific symbolic, artistic, and stylistic feature of a highly “self-conscious” kind possessed by some films as created and intended artworks. It is not an automatic or inherent feature of the film medium as a medium (specific to it) or, for that matter, a universal feature of cinematic presentation/representation or perception as such—although it has been sometimes theorized in both of these ways, on the basis of suggested (and frequently tenuous) analogies between, for example, all cinematography and “self-reflexive” human perception and vision, or all film editing and self-recursive mental processes and consciousness.44 Instead, reflexivity is here aligned with (1) specific creative and referential uses of cinema (that are in no sense simply medium-given), which are, therefore, (2) stylistic and historically shaped and evolving, as well as (3) the result, and special exhibition of, artistic intentions. Conceived in this fashion a film’s (self-)reflexive dimension may be more convincingly brought under the broad umbrella of a fascinatingly varied centuries-old (if not millenniaold) tradition of reflexive exemplification in the arts and literature. It is this history that some filmmakers (as a matter of choice rather than necessity) have both consistently drawn from and contributed greatly to expanding. Of course, for a variety of artistic, actual, and perceived commercial reasons—as relating to the maintenance of a certain form of artistic and fictional “illusion”—other filmmakers (sometimes in accordance with specific styles and the conventions of filmmaking modes and genres) have instead chosen to refrain from exemplifications that focus on a film’s relation to its own form and medium (as a way of expressing something about it) in a relatively more prominent, forceful, or explicit way. Whether or not consciously, their films thereby emulate, or at least share this in common with, notably nonreflexive artistic traditions and practices epitomized by the nineteenth-century realist novel, some theatrical traditions, and certain classical (or premodern) styles of painting.45

This said, however, while some confusion on the point may motivate its scrupulous avoidance in some film practice (and frequent misrepresentation in film theory), as I stressed in the first chapter, although a film’s reflexive level of meaning and apprehension may be “outside” (i.e., distinct from) its denoted confines and its represented fictional and narrative world-in, it is still situated firmly “inside” the total artistic (perceptual and cognitive) field of participation a cinematic work establishes. Thus, rather than something being necessarily taken away from a narrative film’s experience (as a work and as a whole) that would otherwise be operational within it were it not for self-reflexive presentation and foregrounding, it is instead always something else added to what is (and remains) present in terms of the “fictional world” a film generates, for instance, and other referential forms and functions. Put more simply, reflexivity does not necessarily undermine or dissolve a film’s fictional story-world, nor does it prevent or prohibit viewer engagement with it as such or as an imagined or imaginary reality within which viewers may be psychologically and affectively immersed to varying degrees.

Like exemplified features generally, reflexivity is highly relative and variable in terms of its presence across the stylistic spectrum of narrative cinema, found in various modes, movements, and genres (including, one must not forget, classical Hollywood comedies and musicals). It is certainly not confined to modern, or “modernist,” and contemporary “art cinema,” for instance, where it tends to be a prominent and critically noted feature of the films of Godard, Haneke, Wenders, Egoyan, Kiarostami, and other innovate filmmakers. Reflexivity is likewise both relative and variable in terms of the specific meaning contribution it makes to the symbolic-aesthetic dimension of films. As Robert Burgoyne, Sandy Flitterman-Lewis, and Robert Stam have observed, the aesthetic and conceptual ends of reflexivity in cinema are as diverse as its specific means.46 The semantic, referential content of reflexive features within films thus may, or may not, have various cultural critical and “counterideological” meanings, including those that many theorists (e.g., MacCabe, Stephen Heath, and Fredric Jameson) have with all good intentions attempted to invest self-reflexivity as part and parcel of an alternative, nonillusionist (i.e., nonmainstream Hollywood-style) mode of cinematic presentation. No doubt in some notable films reflexive forms and techniques play a substantial part in an intended, or “self-conscious,” critique of the illusionist tendencies of much commercially viable narrative cinema and the dominant cultural ideologies its particular audiovisual form is seen to uphold. Yet as some contemporary horror films and comedies are more than sufficient to demonstrate, films may be at once highly (self-) reflexive and also ideologically moot or reactionary as opposed to social-critical or politically progressive in any sense (as both Stam and Carl Plantinga note). The specific artistic and potentially sociopolitical meaning of a film’s reflexive exemplifications is, in other words, always context- and work-dependent and does not automatically signify whatever it does about either itself, about cinema as a whole, or about wider cultural realities through its lens. Nor, for that matter, and as perhaps cannot be stressed enough, is the presence of reflexivity in a film, any more than the long take, voice-over narration, or allusions to other films, in and of itself any guarantee of artistic or philosophical profundity or value.

Finally, like other forms of exemplification, the intermittent presence and variability of (self-)reflexivity in cinema owes to its high demand for relevant background knowledge on the part of viewers—even if, that is, for latter-day, cinema-literate audiences, especially, the “literacy” in question may be relatively more common and less specialized. It is quite likely that many contemporary viewers would not find it particularly difficult to recognize the major cinematically self-reflexive aspects of Hitchcock’s Rear Window or Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, central to the meaning and interpretation of these films, for instance, given the ways in which these aspects are right on the perceptual and narrative surface of these works. But, doubtlessly, other films, equally as interested in addressing particular aspects of cinema (and its global, national, and local history and practice) through “highlighting” perceptual and referential features of themselves as films—for example, Kiarostami’s Close-Up, Godard’s Notre musique, and Leos Carax’s Holy Motors—are considerably more demanding in this respect. These films, like others, require prior possession of more detailed information concerning cinematic history and techniques, the past works of their directors, more general cultural and historical knowledge, and so forth, to grasp the full import of their reflexive meanings.

As is the case with other symbolic functions at work in the created world of a film, including the other forms of artistic exemplification we have considered—literal (or “formal”), indirect (or “allusive”), and contrastive—reflexivity is rooted in a film’s “objective” perceptual features (as it must be, on some level, to be communicated). Yet reflexivity is not only context-but also response-dependent, since it is only actualized, like a current running through a completed electrical circuit, when cognized by viewers either during a film or after watching it. In its most subtle guises its manifestation may await the instruction provided by film critics and theorists in the discourse of interpretation. As particularly well placed for such recognition and often attentive to it, they may helpfully draw the attention of other “nonprofessional” viewers to its presence and (possible) particular significances. In other words, the necessary role of interpretation as rooted in context and cognitive background entails that there are no unrecognized exemplifications (of any kind) in cinematic works, even if, that is to say, they exist as potentials not yet realized by viewers.

I cannot pretend to deal here adequately with such a large subject clearly deserving of a separate, detailed study.47 Yet from this brief discussion (coupled with earlier observations), it should seem plausible to the reader that a properly theoretical approach to the reflexive in cinematic art from its historical beginnings to the present may be rooted in the concept of symbolic exemplification, working together with an overlapping distinction between the represented-fictional (or “diegetic”) world-in a film and a film world, as the presentational and artistic whole that encompasses it, and much more besides. Such a framework serves to focus attention on the relative, holistic, and contextual attributes of reflexivity as a property and function of cinematic style. As a component of many narrative films standing in relation to other aesthetic, symbolic, and representational features, including literal denotations and an imagination-enabled story-world, it is protean in its possible forms. But to be completely clear on the point, neither is it necessarily in competition with these features, nor does it (always) entail a denial, bracketing, or disruption of a film’s created fictional reality (and of viewers’ pronounced imaginative and affective involvement with it), as is so often mistakenly suggested, implied, or assumed by theorists—ironically enough, both those who actively support and those who actively condemn self-reflexive cinematic strategies and techniques. If nothing else, this overly simplistic, either/or view substantially overlooks the previously analyzed imaginative resiliency of the fictional world-in a film, as rooted in the self-awareness of film viewing, together with our “bifocal” ability as cognitive subjects to “deal with” the representational and presentational, literal and figurative, fictional-narrative and perceptual-aesthetic dimensions of films simultaneously.

SYMBOLIC-AESTHETIC INTERACTION AND INTEGRATION

Having outlined (in fairly abstract terms) the various forms of reference in operation in a film world by virtue of its transformation of its chosen materials, and having seen how some of the resulting aesthetic features or elements may be interpreted as constituting these worlds in various ways, it is necessary to address (more concretely) their profound interaction in films. For quite clearly it is not just the recognized presence of individual symbolic functions in a film and the meanings they serve to convey in isolation that is constitutive of its total experience, or indicative of its artistic interest and significance, but also, and especially, the novel relations among these, in consequence of their deliberate, creative integration.

This fleshing out and bringing to artistic life of reference entails work-created, and to some degree work-specific, relationships, not just between the various types of exemplifications but also between these and cinematic denotations (i.e., as making both internal and external references). Turning to films by Kubrick and Godard—chosen here in part for their canonical familiarity, as well as for their representing very different but equally creative and artistic approaches to narrative cinema—we will first consider what may be regarded as “local” manifestations of such interaction, as pertaining to specific film images, sounds, and sequences. These brief illustrations will be followed by some reflections on the existence of a more “global,” concerted interaction of symbolic forms and functions that occurs on the created and experiential scale of a film work and world as a whole.

Whatever particular aspects of a film world can be picked out from the whole and identified as important aesthetic features may function symbolically in multiple ways that are grasped more or less simultaneously by viewers on the basis of both cinematic experience and knowledge (together with the seemingly innate human capacity to discriminate between distinct levels of meaning and reference in a given image or object). To take a fairly basic example: consider the famous low-level tracking shots down the labyrinthine corridors of the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, utilizing the then recently invented (and now ubiquitous) Steadicam, coupled with the movement of Danny’s (Danny Lloyd) tricycle. As a means of literal representation together with conveying a certain narrative action and development, these sequence-shots serve to further establish the spatial geography of the building’s interior, which plays such a vital role in the actions of the characters as the story unfolds. Much more than this, the image sequences in question simultaneously express a range of feelings: disorientation, claustrophobia, anxiety, and mounting suspense. Some of these affects can be attributed to what the child may be perceived or imagined to be feeling in the situation, while others pertain more strongly to what the viewer may more immediately feel while watching it (or indeed, to where the two may overlap). The represented movement, however—coupled with the jarring yet hypnotic oscillation between the amplified sound of the tricycle’s wheels alternately passing over thick carpets and hardwood floors—also serves to crystallize a particular constellation of affect into what T. S. Eliot famously called an “objective correlative.”48 In other words, it creates a perceptible symbolic-affective figuration unique to the film and, hence, a metaphorical exemplification that may be understood irrespective of the recognized presence in the viewer of any of the feelings in question and what the character is empathetically understood to be feeling. (The sequences and this feeling thus contribute to The Shining’s particular manifestation of what I will later analyze as the total “world-feeling” of a cinematic work.)

Additionally, however, for viewers who recognize it, the literal, readily perceived action also formally exemplifies the unusually composed and emphasized forward-tracking movement of the camera as such, recording and re-presenting it. Not only is such camera movement a virtuosic display of technique, and a crucial stylistic and structural principle of the film’s design, but it is also a powerful variation on the elaborate, temporally extended forward and backward camera movement found in all of Kubrick’s feature films (as partly indebted to the acknowledged influence of Max Ophüls) and widely associated with the director. It is to these other films and instances that these sequences thereby allud e, together with exemplifying this aspect of Kubrick’s signature style (and of his cinematic worlds built upon it); they thus invite comparison between the form and meaning of the camera movement in The Shining and in other films. Finally, for viewers aware of it, the moving-camera images and sequences also call attention to the formal-technical and aesthetic capacities and potentials of the Steadicam specifically (here operated by its inventor, Garret Brown), the subsequent uses of which also provide a fascinating lens through which to retrospectively view its early appearance and use in The Shining. In sum, the vision-based polysemy found here—as following from all such multiple but integrated and near-simultaneous, sensible, affective, and cognitive (and affective) functioning of roughly the same aspect or feature within a film—is, it must be stressed, to be found in a good deal of narrative cinema. On reflection it is also a significant part of its characteristically artistic, and artistically interesting and successful, uses and experiences.

As well as being one of the most visually beautiful films ever made, Le mépris is arguably one of Godard’s most technically and formally accomplished works. This owes, not least, to the combination of Raoul Coutard’s cinematography, Georges Delerue’s celebrated score, and an innovative use of the widescreen (“Franscope”) format, the long-take sequence shot, and expressive color. But it is the ways in which such formal aspects semantically and affectively interact with characters, story, and drama, on the one hand, and exemplifications pertaining to a host of cultural objects and phenomena—and (reflexively) to the film’s own creation, sources, and cinematic context—on the other, that makes it such a compelling and rich aesthetic experience. Another example of symbolic integration in cinematic art on the “local” level of the sequence (or scene), as drawn from Le mépris, is worth pursuing in some detail. Together with the complex integration and overlapping of referential and artistic functions, it also serves to highlight some (possible) relations between such reference-making and the artistic-stylistic features and transformations addressed in the previous chapter in terms of specific, higher-order world-making processes.

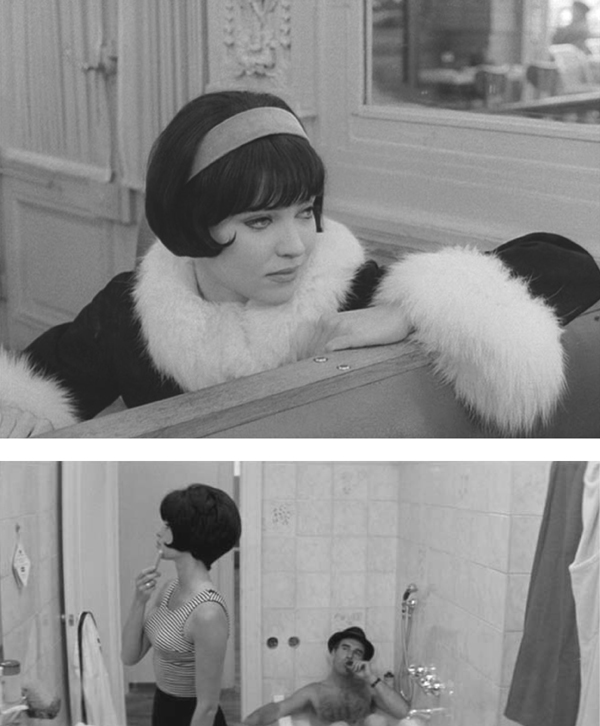

In the couple’s rented Roman apartment, just prior to the bitter marital quarrel that occupies the narrative and thematic center of the film (intermittently extending over nearly twenty minutes of screen time), Camille, played by Brigitte Bardot, dons a recently purchased black wig, denoting her as a brunette with a distinctive hairstyle. Entering the narrow bathroom where Paul (Michel Piccoli), with hat and cigar, reclines in the bathtub, Camille asks him if the wig and its style suits her, to which he tersely replies that he prefers her as a blonde. She retorts that she prefers him without the hat, which he then claims to be sporting in order to look like Dean Martin (referring to Martin’s character Bama, in Vincente Minnelli’s 1958 film Some Came Running).

Literally foregrounded (or, in Goodman’s analogous term, weighted) through the situation represented, and through cinematic composition, with the narrow bathroom forcing her into the perspectival front of the image, Camille/Bardot’s appearance exemplifies brunette actress Anna Karina, together (for cognizant viewers) with Godard’s famous on- and offscreen relationship with her. Since, that is, both Karina’s hair color and its particular style—as so prominently showcased in Godard’s earlier Vivre sa vie, including in its opening titles sequence—are here referenced and visually echoed through Camille’s temporarily altered appearance (figs. 5.1, 5.2).49 Made two years before Le mépris, Vivre sa vie established Karina as the director’s on- and offscreen muse, the two having been married shortly before its making and having separated by the time of Le mépris’s shooting (an Italian poster for Vivre sa vie that prominently features Karina appears early in Le mépris). Throughout the couple’s argument, Camille/Bardot adopts a number of poses and gestures highly reminiscent of Karina and her character in Vivre sa vie. Most notably, after being slapped by Paul, and still wearing the wig, she is captured in a profile close-up, pressed against a white wall, head down, in images that mirror recurring shots of Nana/Karina in Vivre sa vie, especially those occurring within the earlier film’s highly reflexive and autobiographical “Oval Portrait” sequence (often interpreted as a cinematic celebration of affection for Karina on Godard’s part as much as for the character of Nana on the part of her young suitor, within the film’s story).50

Appropriately enough, given this particular allusive and self-reflexive context, Godard’s and Karina’s highly public relationship is present in Le mépris in the form of a schematic, cinematic distortion of it, one that approaches (self-)parody through the highly ironic, mediating presence of Bardot, the “blonde bombshell,” as a perceived stand-in, or distorted double, for brunette Karina, who had played the female lead in Godard’s three previous feature films. Bardot is at once Camille and the most famous female celebrity—and blonde star—who could possibly be cast in her role. Through the symbolic mode of contrastive exemplification her presence serves to underscore Karina’s conspicuous absence from the film. As constructed by means of this clever mirroring, within a mise-en-abyme film concerned on so many different levels with the often puzzling relations among film, art, and life, the costume and mise-en-scène in this sequence thereby establish two distinct yet overlapping channels of meaning, as well as emotion and affect. One (Paul and Camille) proceeds through denoted fiction and drama (and the represented world-in the film); the other (Godard and Karina) proceeds through its artistic presentation (as part of the experienced world-of the film) and (by way of it) allusion to extrinsic, autobiographical realities the film creatively incorporates.51

FIGURES 5.1 AND 5.2 A dense network of reference and association in Godard’s 1960s cinema centering on Anna Karina (Vivre sa vie), Brigitte Bardot (Le mépris), and a hairstyle.

Visually, as well as through dialogue, these differently oriented yet also converging referential meanings are also supplemented (and further supported) by prominent “intercinematic” allusions to two other seemingly passionate yet mismatched and slowly disintegrating romantic relationships—namely, as they are portrayed in Minnelli’s Some Came Running and Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (also more literally present in Le mépris in the form of a cinema marquee), respectively. These two films provide a rich source of world-making material for Le mépris. Indeed, when (or if) viewed in comparison with them, Godard’s film can be seen as radically amplifying, “recasting,” and reverently distorting (in Goodman’s sense) not only many of their themes and tragic-romantic narrative situations but prominent formal features, including the arresting widescreen (CinemaScope) compositions, languorous long takes, and bold primary color schemes of Minnelli’s film, all of which are present and accounted for in the argument sequence in Le mépris.

There are also other potential, and less (directly) autobiographical, allusive pathways here, which move in the direction of comment on film genre, in this case the suspense thriller and film noir (or neonoir) iconography. Camille/Bardot’s altered appearance may be taken to look back on, or indeed anticipate, several films, from Hitchcock (Vertigo, North by Northwest) to Lynch (Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway), in which a femme fatale and love interest metamorphoses to the extent of her visible hair color at a pivotal dramatic moment within the story and plot. When taken in the context of noir—with which Le mépris shares many “deconstructed” characteristics—Camille/Bardot’s temporary transformation (and Karina’s presence-in-absence) foregrounds the bifurcation of female presence in noir through conventional dualisms (blonde/brunette, good/evil, innocent/guilty, chaste/promiscuous).

In all of the ways noted (and which could be significantly expanded in a number of directions), Le mépris aptly illustrates the notable multiplication of the (forms of) references that even a single cinematic image or episode may sustain when juxtaposed with the work as a whole, translating into a remarkable cognitive and affective density. Although, as I mentioned previously, and as numerous commentators have pointed out, such density is a pronounced stylistic hallmark of Godard’s films of the 1960s and beyond (and of particular film styles or modes with which they may be associated), this complexity and richness of extranarrative meaning, and its “multitrack” character, is also to be found, if in admittedly different manifestations and degrees, in most creative, artistically ambitious and interesting narrative films.

With respect to the aesthetic features picked out, this one episode from Le mépris also shows the extent to which character and performance may serve as a nexus for multiple and overlapping referential articulations with extranarrative, artistic significance. Through their sheer bodily presence, voices, mannerisms, and so forth, but also their typical roles, and the genres and specific films with which they are associated, actors and actresses, as film-world “material,” are frequently associative bridges connecting the different cinematic worlds through which they freely travel, as it were. Indeed, all casting in filmmaking, as a creative and transformative activity in-itself, requires particularly close consideration on the part of filmmakers to denotational, expressive, reflexive, and allusive meanings tied to performers, as quite literally “living symbols.” This of course includes a great deal of anticipation on the filmmaker’s part regarding what the use of certain actors or actresses, stars or nonstars, may communicate or express through existing cinematic and wider cultural associations. Such deliberations and fine judgments are not dissimilar to those that may also surround the use (and choice of) preexisting pieces of music in a film or the decision to opt for an original musical score instead (that is, with less associative aspects). Casting decisions may have equally “global” consequences for aesthetic meaning and feeling, with the power to shape the entire tone and meaning of a cinematic work-world, as numerous filmmakers have admitted and discussed.

GLOBAL AND TEMPORAL SYMBOLIC CONSTRUCTION

Unlike paintings and still photographs, which present their symbolic world-structures all at once as it were, in the simultaneity of spatial presence to hand, temporally conditioned artworks like films add a crucial dynamic and dialectical element to symbolic interaction on larger—and longer—scales. It is the unfolding progression of sequences and episodes, rather than discrete shots and images, and their contents that primarily condition and enable such interaction. In what might be analyzed as the horizontal, “melodic” structure of a film (as distinct from its interrelated, vertical, and “harmonic” ones), one or perhaps several types of symbolic articulation may come to the fore and temporarily supersede or dominate others as a film unfolds.

Aptly, in this connection, one finds Goodman’s only substantial, explicit reference to cinema in Languages of Art. He suggests that in Resnais’s and Robbe-Grillet’s Last Year at Marienbad—a landmark in the evolution of nonlinear cinematic narrative and formal experimentation—denotation, expression, and formal exemplification as “fused or in counterpoint” are equally present and prominent. Yet they are featured in alternating fashion, since “the narrative thread, though never abandoned, is disrupted to let through insistent cadences and virtually indescribable sensory and emotional qualities.” (With reference to which particular symbolic function temporarily outweighs others in a film or any artwork, Goodman pertinently adds that “the choice is up to the artist and judgment up to the critic.”)52

To further expand on Goodman’s typically trenchant and here rather underdeveloped observations, in the course of narrative films, after a foundation of literal and fictive denotation has been well established, via, for instance, establishing shots, exposition in dialogue, and so forth, such representation may then recede—literally, with respect to perceptual contents of images, or figuratively, with respect to its relative importance as an object of viewer attention, knowledge, and feeling—while, at the same time, formal exemplification comes to the fore. Or, in marked contrast, expression and one or more types of exemplification together may serve to deemphasize mimetic representation from the beginning of a film, while, for instance, viewers await the piecing together of a comprehensible narrative structure.

An even more pronounced and telling example than Last Year at Marienbad is 2001: A Space Odyssey. A great deal of the film (nearly two-thirds) is given over to a meticulous “hyperreal” denotation of extraterrestrial environments, with an emphasis on conveying the fictional world-in of the film with maximal visual clarity and definition. This is achieved through in-built set lighting, superfast lenses, the use of highly detailed models and other special effects, and an avoidance of subjective point-of-view shots and constructions (and the psychological and perceptual impressionism and ambiguity often attached to them).53 Such factual, third-person objectivity and a visually rendered and documentary-like concern with concrete physical details and processes mirror, and overlap, the emotionally detached observing and reporting activities of the astronauts on their interplanetary mission.