Mapping Affect and Emotions in Films

FILM WORLDS ARE FELT AS MUCH AS THEY ARE PERCEIVED AND known. Indeed, it is their global affective character, in a sense to be explained, together (and in interaction) with other expressive aspects, that accounts perhaps most directly for their singular, world-like mode of existence. For reasons that will become more apparent as we proceed, a better understanding of a distinctly aesthetic affective presence in cinema, and of related phenomena of viewer engagement and immersion, necessitates first achieving a firmer hold on the complexities of the conveyance of feelings and emotions by narrative films more generally.

Although it is certainly appropriate to pursue this subject under the single heading of “expression,” this may also be a source of semantic and conceptual confusion.1 The term has a variety of meanings in relation to art and its reception, and there seems little consensus about the relative priorities of these senses for aesthetic theory or even what sort of phenomena, exactly, are being referred to by its use. Such polysemy and, in some cases, outright ambiguity is also found in discussions of cinematic expression, as a “widely recognized point or purpose of films,”2 whether or not these purport to be concerned with any specifically artistic or aesthetic variety of it.

By tradition, expression refers to the conveyance of feelings, emotions, or other uniquely human properties or qualities, such as character traits, in and through artworks by means of their sensory forms and representations.3 But it may also be taken to refer more specifically to the artist’s communication of his or her own thoughts and feelings: a revelation of inmost subjectivity somehow transmitted by or through a work, as reflected in the canonical “Expression Theory” of art, associated primarily with the writings of the Italian idealist philosopher Benedetto Croce and his British follower R. G. Collingwood (together with earlier romantic conceptions of art).4 Finally, artistic expression has been taken to mean any creative stylization and original artistic interpretation of familiar realities that has affective as well as formal aspects, as in German expressionist cinema or the typical works of expressionism as an early twentieth-century movement in the fine arts. As we have seen, it is expression in something more akin to this last sense, in particular, which is at the center of Mitry’s account of film as art, as it is in Pasolini’s. There are important ways in which all of these familiar meanings of the term may overlap in cinematic art, as we will consider. Yet for the bulk of this chapter I will be using expression primarily as a shorthand description synonymous with any affect, feeling, or emotion prompted by a film that is actually felt to varying degrees by an engaged viewer, beyond being only intellectually recognized as somehow present.

In the past few decades a number of theorists and philosophers, including those with backgrounds in other disciplines (e.g., psychology), have concentrated a great deal of attention on emotion in narrative cinema. The topic has been discussed and analyzed mainly in relation to representational and narrative-fictional contents of film images and sequences, as generating emotions and other sorts of affective responses through perceptions, beliefs, and other cognitive states of viewers. In keeping with the frequent equation by theorists of cinematic works (and worlds) with visually composed narratives and fictional story-worlds, many of the varied sources of affective expression in films (not least owing to their sensory and formal properties) have been somewhat overshadowed by, for example, debates over the nature and extent of character and situation “identification” and whether, and in what senses, film-viewer emotions are “real.” The relations among expression, as intentionally placed affective and emotive content, and formal and aesthetic features of cinematic works have tended to be neglected in these problem contexts (so much so, in fact, that some of these discussions and arguments could be transferred to the study of literature with few, if any, alterations).

Yet in attempting to give due recognition and provide a proper place for feeling attached to nonfictional and nonrepresentational features and qualities of narrative films as distinctly audiovisual and presentational objects and works, it is also crucial not to engage in an equally problematic full-scale retreat from all that is representational, cognitive, thematically normative, and reflective in film viewing or from the many types of symbolic mediation it involves. Such a retreat characterizes some recently forwarded anti-Cartesian accounts of film affect and sensation.5 Drawing on various extracinematic theories and philosophies of affect, sensation, and embodiment in Continental theory and philosophy, these are explicitly or implicitly cast as alternatives, better grounded in actual phenomena of film-viewer perception and immersion, to the cognitivist views favored by other analysts.

Avoiding such polarization of approaches, and overly binary theorization, a more reasonable and productive course, it would seem, is to admit a multiplicity of sources of feeling in cinematic experience: cognitive and noncognitive, perception- and imagination-based, visual and aural, image- and soundtrack-elicited alike. This recognition points to a strategy of assigning specific sorts of expression and affective dynamics to appropriate parts or levels of films and to different ways of experiencing them.

Like the different, interlocking forms of symbolic reference constituting the semantic structure of cinematic works, instances of these distinct sorts of affective and emotional conveyance and response may be quite tightly and complexly intertwined in specific films and in our viewing encounters. To a degree, however, they may still be usefully isolated for the purposes of theorization. And, just as isolating and identifying a cinematic work’s and world’s constitutive, symbolic functions can serve to reveal which of these (or which interactions among them) tend to be relatively more artistically important, so, too, can differentiating between a film’s affective and expressive components in more systematic fashion help to identify the extent and nature of their respective contributions to its aesthetic experience, interpretation, and the human truths it may disclose.

With these aims in mind, it is perhaps most helpful to begin with consideration of how feeling in cinema has been typically dealt with in recent cognitive and analytic film theory and the philosophy of film. Several writers adopting this approach, and building on research on human emotions generally, have established intellectual frameworks and connections that appear consistent in some important respects with the analysis and typology that, as I am suggesting, emerges quite naturally from the direct experience of many films.

FEELING, EMOTION, AND IDENTIFICATION

Among most contemporary philosophers interested in the topic, emotions are not conceived of as a species of the genus of feelings, but are, rather, to be distinguished as a class from feelings, taken as all merely physical states and affections of which we happen to be consciously aware. The label of emotion is, in other words, reserved for affections that have intentional objects so that with respect to the experience of any “proper” emotion, it is always possible, in principle, to find an accompanying state of belief as to the identity of its source or subject. Several current film theorists and philosophers of film follow this preference in regard to divorcing emotions from feelings (including, from a more cultural and media-studies perspective, Brian Massumi in his influential writings on affect).6 The distinction also happens to have a more general precedent in writings on cinema, where terms such as mood, tone, and general atmosphere are often used to refer to palpable, affective qualities that have identifiable sources but no single, definite objects—unless, as we will see, the object in question, responsible for a genuine and distinct emotion, is a film as a whole, or some significant part of it.

Carl Plantinga, one of the leading theorists of emotion in cinema, flatly states that “a cognitive approach holds that an emotional state is one in which some physical state of felt agitation is caused by an individual’s construal and evaluation of his situation.”7 Emotions are, in other words, always accompanied by beliefs—or, as some philosophers prefer to hedge their bets, so-called belief-like states—whether or not these are fully articulated during the occasions when emotions are felt. In his comprehensive study of affects in narrative cinema, which aptly characterizes most mainstream films as veritable “emotion machines,” the psychologist Ed S. Tan concludes that the “one postulate” recent Anglophone philosophical accounts of film have in common “is that some form or other of cognitive activity mediates between the stimulus and emotional response.”8 Such a view is encapsulated by Berys Gaut as the “cognitive-evaluative theory of emotions.”9 In what is now a small library of writings on the expressive potential of fiction films in this sense, Plantinga, Carroll, Greg E. Smith, Murray Smith, Gaut, and others adopt essentially the same general position, assuming the causation of all proper emotions by our perceptual construals, or thoughts. With the connection between the representational contents of images and their emotional values, if any, thus assured, they tie film emotions to viewer knowledge and to the designs of (mostly) mainstream films, wherein this cognitive activity is seen as supported by more clearly comprehensible narratives, genre expectations, and a general visual and spatial-temporal realism and naturalism, as opposed to major formal stylization or narrative experimentation.10

Predictably, there has also been a critical reaction and response by other writers to this strongly cognitivist position as borrowed largely from mainstream philosophical studies in such fields as ethics and philosophy of mind. For example, drawing support from some famous insights of Wittgenstein concerning the indivisibility of our mental acts and the external facts that supposedly cause them, Malcolm Turvey has argued that the standard account in terms of cognitive objects and evaluations that precede emotional experiences fails to fit the phenomenological facts: at least in many cases of visceral or “gut-level” emotions that many contemporary films not only elicit but quite obviously aim to elicit.11 As we will see, however, so long as it is not assumed that all emotions (or emotive responses) instantiated by films are clearly mediated by beliefs or other cognitive states linked to fictional representations, there is certainly an advantage in distinguishing between (a) such explicitly informed or “higher” states of feeling content and (b) other sorts of more immediate (and perhaps natural, and universal) affective responses, including (but not limited to) “raw” feels, shocks, surprises, and other, sometimes noticeably physiological, reactions to what appears on the screen or the soundtrack.

Another point of contention is the extent to which emotional engagement and response in cinema are secured primarily through character identification or through viewer perception of narrative fictive situations apart from any particular attitude or feeling about characters and as the locus of what Carroll refers to as emotional “prefocusing” on the part of filmmakers. This latter is seen to involve specially designed situations in the diegetic dimension assisted by the entire range of medium-specific enhancements, including camera position, editing, lighting, use of color, and, of course, musical underscoring, which establishes criteria that amount to reasons for having certain emotions, ones that overlap with such situations in noncinematic experience.12 Despite their much-argued differences, however, in one way or another both of these accounts turn on specific feelings generated by and through the viewer’s engagements with literal or fictive representations within the story-world (what I have termed the world-in a film); they thus fall somewhere short of reaching the plane of the aesthetic, as it might be said.

Drawing on Burch, Bordwell, and other writers whom he collectively refers to as “story theorists,” Tan makes heavy use of the concepts of the “diegetic effect” of films and their fictional worlds. He also recognizes, however, that not all production of emotions by films is “situational,” that is, based on the viewer imagining himself or herself present within the reality established by a fictional narrative.13 In fact, he distinguishes two basic kinds of emotions present in film experience: fictional emotions and artifact emotions. “F-emotions” (in Tan’s abbreviation) are the result of the viewer’s acquiescing and submitting to the so-called magic window of the diegesis and having thus entered into the story-world of a film, reacting almost as if present in some capacity in that world. “A-emotions,” however, are aroused or elicited by a film when it is regarded as an object and a created artifact, viewed and thought of from an external or non-imaginatively engaged and fiction-accepting standpoint.14

Unlike F-emotions, which for all the intensity they may muster remain essentially vicarious from a factual, “real-world” perspective, A-emotions may be as fully genuine, as “real,” as any of those triggered elsewhere in life (even if they are seldom of the kinds associated with physical consequences). Plantinga, who generally accepts Tan’s distinction, suggests that “exhilaration at a particularly brilliant camera movement” and the “pleasure and enjoyment” of one film’s allusions to others are prime examples of A-emotion, which is always at least implicitly mindful of a film qua created object and artwork.15 Such emotions are, in other words, fundamentally about the cinematic work, in recognition of its created nature and functions. They require gaining some more work- and self-aware perspective on the viewer’s part about broadly artistic uses of the medium to certain creative and meaningful ends, together with entailing the possession of the knowledge this may entail.

Such “distance,” however, does not mean ignoring narrative-fictional realities and what we have defined as the world-in films. But, as in Plantinga’s second example, such emotion necessarily involves some grasp of a film’s nonliteral or nondenotational representations, of just the sorts we considered in the previous chapter under the heading of artistic exemplifications (e.g., allusions). These remain separate as a class from those emotions that may be felt only in consequence of the viewer’s implicit decision to participate in the fiction-making enterprise. In basic terms, such F-emotions, but not (necessarily) A-ones, require the film viewer to imaginatively assume the position of a participant or witness with respect to the action of the narrative, to be imaginatively immersed within it in a more general way. This may be termed “imagining from the inside,” in Murray Smith’s phrase, which echoes philosopher R. K. Elliott’s earlier, more general notion of experiencing any representational artwork “from within” its posited reality as opposed to “without” (i.e., experiencing it from a greater psychic distance, as a created rendering or simulation).16

Tan’s account of the typical feature film as nothing less than a near-perfect device for triggering emotions rightly makes an allowance for the ontological and experiential differences between a film work’s fictional representations (which combine to form the story it narrates) and features of the larger created, presentational whole of which these are part. In other words, this is in keeping with our present distinction of the world-in and the more encompassing world-of a film. The analysis also aptly suggests that cinematic emotions may be plausibly divided between those that are more pertinent to art and to the aesthetic dimension (i.e., as work-centered, involving attention to extranarrative features and intentions) and those that primarily pertain to film as a medium exceptionally well-suited to constructing fictional domains and credible characters to inhabit them and be engaged with as such, and sometimes exclusively. Moreover, Tan’s distinction remains useful even if, as Plantinga argues, the two types of emotion may be often simultaneous and indistinct in their particular instances in actual film experience.17

Given the overriding focus of his study on F-emotions, however, Tan, like Plantinga, devotes comparatively little attention to further explicating A-emotions or the sorts of real relations obtaining between each type. Nonetheless, here again falling into that pattern of recent theory we have already observed, he tacitly assumes that (a) the only “world” of a film in which the viewer may be affectively immersed while experiencing it is that of diegetic fiction, and (b) that a great deal of what pertains to the work qua artwork, and to aesthetic attention (or the “aesthetic attitude”), is generally antithetical to a pronounced experiential absorption and immersion, given the lack of reflective spectator distance the latter is assumed to involve.

Yet if film worlds are more than story-worlds, then it is also likely that not all strongly immersive feeling and affect is a function of engaging in particular ways with represented situations and the fortunes and misfortunes of dramatic characters. In fact, at least some generally comparable expression and potential for immersion is shared by both narrative and nonnarrative films, the latter typically having no characters or diegetic fiction to speak of; it is also part of the experience of artworks in other forms and media, narrative and representational, and nonnarrative and nonrepresentational, alike. There seems to be no a priori (or empirical) reason why cinematic expression and its fostering of immersive engagement should be confined to an attribute of the diegesis or to acceptance of the fiction and its many ramified, ontological projections, as such, or why this process should be fully reducible to these in theoretical terms. Put more simply, we may accept the distinction of A- and F-emotions as a useful starting point without concluding that all cinematic immersion is a matter of “emotion-belief” focused entirely on character, story, and plot situations. As I will discuss in more detail in the next chapter, it is equally born of an intentional, active, and participatory engagement with a film as a work of art and an unfolding sensory, as well as cognitive, experience compelling our attentions and feelings as such.

Apart from the distinctions outlined thus far, cinematic experience typically encompasses numerous levels or kinds of feelings and emotions, ranging from the most visceral and reactive to the most complex, subtle, sublime, and reflective. Clearly, as most theorists recognize, not all of these responses elicited or in play for film viewers are of the same kind, nor do they have the same sorts of sources or objects. In consequence, I believe that film affect and emotion are too variable and complex to be satisfactorily treated from any one systematizing theoretical perspective, or single model, such as psychological-cognitive, phenomenological, “sensuous,” or “haptic.” Each of these now common theoretical perspectives, however, proves to have some utility in approaching and understanding the manifestations of this prominent dimension in which cinema finds a major ground of continuity with other, older arts.

Cognitive theories provide some valuable insights into some forms of emotional or affective engagement and immersion in some film worlds (as artwork worlds) or, perhaps more precisely, some parts or moments of them. But these appear to be bought at the price of too narrow a focus on certain F-emotions, as we have considered. Indeed, if we start from the traditional premise, supported by the more broad-based views of such thinkers as Cassirer and Langer, Mitry and Dufrenne, among others, that it is affective expression of certain kinds (or with certain goals) that in part distinguishes the experience of art from other experiences in the vast domain of symbolic representation, we will inevitably come to perceive the methodological sources of this limitation of the scope of recent treatments of film-created emotions in specifically aesthetic terms. Most cognitivist approaches, we must remember, are anchored in “everyday” perceptual and psychological dynamics that are specific neither to cinema nor to art,18 and yet are explicitly seen, with some clear truth, as always operational to various degrees when we engage with films. This focus generally (and to some extent, necessarily) emphasizes cinema’s realism, in the sense of the mimetic or substitutional potentials of the medium, over its more creative transformational ones. While narrative cinematic art clearly pertains to, and makes use of the former, it is equally, if not more, a matter of the latter.

LOCAL AND GLOBAL CINEMATIC EXPRESSION

With all these considerations in mind, we may attempt to roughly map the total affective field of a narrative film. It may be seen to comprise three forms of local expression, together with one more global, composite expression or “world-feeling” of an aesthetic nature. To an extent mirroring the previous analysis of “local” and “global” integration and interaction with respect to the forms and objects of symbolic reference in film, these terms are here intended in a primarily temporal and experiential sense, as opposed to any literal physical and spatial one. Plantinga distinguishes between some specific types of emotion in the experience of films on the basis of the relative temporal duration of the emotions in question. Those that are “long-lasting” and “spanning significant portions of a film” (e.g., suspense) he terms “global,” and those that are “intense” and “brief in duration” (e.g., surprise and elation) are “local.”19 Although my use of these designations overlaps somewhat with this recent author’s, given our different, more expansive concept of the world of a film, these same terms have an additional, deeper, and differently oriented significance here. Moreover, local expression, in my present sense, which might also be called episodic, pertains to potentially any emotions, feelings, and affects that are associated with specific and given images, sounds, and sequences (or entire dramatic scenes). The main point is that in the temporal movement of North by Northwest or Caché, as in almost any narrative film, specific emotion-eliciting images or sounds are soon succeeded by others, and so forth, which typically involve other, often quite different and contrasting affects. By comparison, global expression, as the label suggests, pertains to a film work as a temporal whole and as incorporating and integrating some number of local or episodic affective sources.

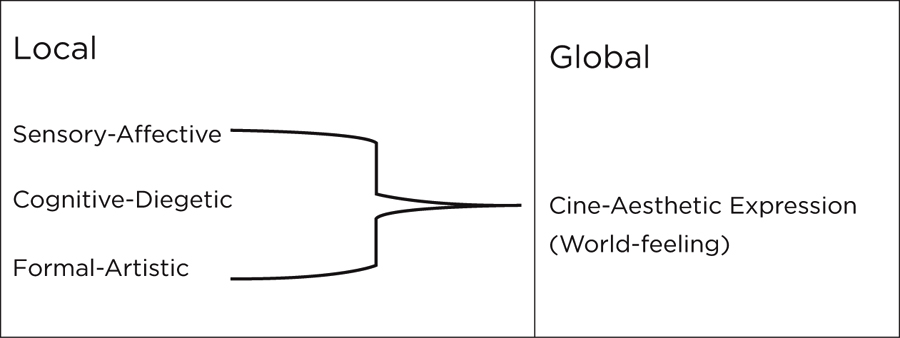

More specifically, local cinematic expression may be seen to comprise three general forms: (1) the sensory-affective, which tends toward the immediate, visceral, and “natural” (i.e., likely biologically “hardwired” in contemporary parlance); (2) the emotive-cognitive, or what I will refer to as cognitive-diegetic, working through fictional representation and imaginative participation or identification of some sort; and (3) the formal-artistic, involving responses to features of a film that center on their evincing aesthetic properties of form, design, and artistic intentionality and significance (fig. 6.1).20

FIGURE 6.1 Cinematic Affect and Emotion.

Each of these basic types of expression may be distinguished from the others in terms of its most typical causes or sources in a film’s presented images and sounds (although these may also be shared), as well as phenomenological differences in the viewer’s awareness of, and attitudes toward, such “objects.” As distinct or as overlapping as they may be in any given film, these varieties of local cinematic expression are complemented by one global or total form of aesthetic affectivity, to which at least some of them contribute. To revert to our primary distinction with respect to literal representations as establishing a film’s fictional reality, and the formal and figurative presentation that creates a larger semantic and affective context for this reality’s experience—that is, a film world—this last category of affect is as much of a cinematic work as in, or part of, it.

FORMS OF LOCAL FILM-WORLD EXPRESSION

Sensory-Affective Expression

What I call sensory-affective expressions are likely the most familiar and ubiquitous throughout cinematic experience, accessible to audience members of every description. They represent the most direct and immediate, nonreflective feeling responses prompted by perceptual attention. They may also lack a specific narrative or fictional (together with what I will describe as “formal-artistic”) cause or basis per se. In an eponymous book the philosopher of mind Jesse Prinz uses the phrase “gut-level emotions” to designate specific feeling contents that seem to lack cognitive objects, at least at the time of their occurrence.21 Prinz, Jon Elster, and other recent writers on the nature of such emotions take these to be wholly unreflective affective reactions to certain perceptual stimuli or internal, physiological changes.22 Along these lines, such feeling elements or emotional triggers are the least culturally and symbolically mediated sort of affect in film experience. They are a matter of the most “natural” of expressive contents, readily accessible in the cinematic event and routinely called upon by filmmakers to elicit elemental, panhuman affects.23 Such elementary, perceptually given sources of stimulation result in what psychologists refer to as emotional invariants or universals, to the extent that the cinema harnesses them, in the form of two-dimensional simulations, for shocking, entertaining, and, sometimes at least, more creative, artistic, and thematic purposes.

In relation to composition, movement, gestures, rhythm, and above all editing, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Vertov, and other early Soviet filmmakers were at the forefront of systematically studying and practically exploring this first general mode of filmic expression, in an attempt to incorporate it into cinematic narratives conceived as total audiovisual experiences. Other early film pioneers like Griffith and Murnau may be seen to have pursued this vast medium potential on a rather more intuitive basis. The practices and techniques used by filmmakers and, today especially, special-effects engineers and sound designers, to produce sensory-affective expressions are, of course, numerous. They may result from editing, in-frame motion, camera movement, the use of sound effects and music (both in themselves and in concert with the image), CGI manipulations, and all manner of kinesthetic and audiovisual capacities for stimulating the viewer’s innate physiological mechanisms. In adding sounds to sights, and using the elements of shock and surprise, there appears to be no end to the sorts of instinctual, sense-driven, virtually instantaneous states of feeling that films can provoke. As may be seen in many early avant-garde films, such as Man with a Movie Camera and Entr’acte (where the camera is memorably taken on a roller-coaster ride, some of the movement, force, and speed of which is transferred to the viewer), this is a mode of filmic expression and contact with audiences that, while never wholly independent from the specific representational contents of the film image, may be the most “indifferent” to them (and sign and symbol relations) even in the context of a narrative film.

However, it is not only aspects of a film’s particular sensory and formal presentation that may provoke such local affect but, rather, imagistic content per se. This second subtype of episodic sensory affect returns us to the topic of naturally or inherently expressive filmmaking materials borrowed from our common lifeworlds (briefly discussed in chapter 3), which can now be addressed in greater depth. This expression is strongly tied to what Souriau first termed the “profilmic” and what Metz refers to as the “filmed spectacle” as distinct from the spectacle of a film.24 Such affect is a consequence of the sheer, readily recognized (mimetic) presence onscreen of a grotesque, painful, joyous, shocking, or erotic object, event, or situation, for instance, rather than the proximate consequence of its narrative-fictional position or purpose or, for that matter, its specific cinematic and artistic presentation. In other words, this affect is defined by an unbroken connection to what a film either necessarily retains or allows for, in affective terms, from the objects, bodies, faces, gestures, or other naturally (and to some degree, culturally) expressive materials it represents and uses, apart from whatever (further) creative and stylistic transformations these may have also undergone in the artistic filmmaking process. As described by Mitry, reliance is placed here on “the obvious power of an intrinsically moving reality,” which the basic, iconic “image-data” of a film captures and transmits.25

Accounting for some significant part of their mass appeal, filmed objects and events may, as it is hardly necessary to argue, generate much the same feeling responses that their actual, sense-experience-occasioned counterparts would if encountered in everyday, bodily present, three-dimensional reality. (Conforming to what film experience has seemingly long suggested, some recent scientific studies of the subject have concluded that for some feeling-related areas of the brain, real objects and their imagistic representations are close to indistinguishable in this emotive respect.)26 While in both a celluloid and digital context such affectively charged representations are typically indexical—that is, physically causally connected to that which the film camera has recorded—this is not necessarily a determining factor in the generation of such feeling contents and response. This is because sensory-affective expression of this kind is present not only in relation to all forms of animation, for instance, but also representational painting, drawing, and sculpture. Yet to the extent that, first, the indexical relation carries through into the ease of apprehension of the contents of film images, and, second, given the standard level of verisimilitude typical of (although not essential to) the photographic and live-action film (with its attendant, psychological impacts), this sort of sensory-affect may be considerably amplified in cinema relative to other forms and media.27

Any such retained profilmic affect may be used in all sorts of creative, interesting, and artistically significant ways, as is perhaps most obvious in the many different aesthetic functions and appearances of the facial close-up (where the very word expression has another, pertinent sense). Yet, on the other end of the spectrum, as often requiring little in the way of artistic creativity, a blatant, highly manipulative employment of this mode of affect, as tied to the visual exhibition of a highly stimulating, shocking, taboo or confrontational subject matter—as a cinematic end rather than means—is, of course, not only possible but a hallmark of so-called exploitation cinema.28 In a way that supports our present classifications, however, there may also be only the finest of lines between art and exploitation in this respect, which directors like Tod Browning, Walerian Borowczyk, and Alejandro Jodorowsky have notoriously attempted to walk in films such as Freaks, Labête, and El topo, in seeking to channel such affect in thought-provoking ways.

Returning to our previous discussion of cinema’s world-making materials: in an artistic context any such “given” emotive contents (or so-called valences) must, it appears, be harnessed, controlled, and manipulated in such a way as to serve a filmmaker’s creative ends and intentions, as Mitry, Metz, and Pasolini maintain. Lest one suppose that the “problem” of the natural (or inherent) affective expression of materials in cinema emphasized by these theorists is a critical or theoretical supposition alone, we need only briefly reflect on the considerable amount of creativity, resourcefulness, and technological innovation that has been devoted to altering and controlling the profilmic affective “messages” often transmitted by the faces, voices and body language of performers; by colors, light, and natural sounds; and by much else besides, in many and varied filmmaking modes, genres, and styles throughout cinema’s history. Here we find ample evidence that such manipulation and transformation to more creatively manage this expression has indeed been, in practice, both a difficult and necessary task. In the planning of any given film, as well, decisions to shoot in a studio rather than on location, or in black and white rather than color, may be artistic as often as practical or economic, informed by these considerations pertaining to the avoidance of unwanted affective “interference” stemming from the nature and appearances of the properties of almost anything present within the frame or on the soundtrack.

As an opportunity for enhanced creativity, as much as an obstacle to it, however, the specific and varied ways in which such mimetic sensoryaffective expression has been (successfully) harnessed and employed has, in turn, shaped the signature artistic styles of a number of filmmakers considered among the greatest. A few well-known examples drawn from canonical European art cinema include Bresson’s efforts to proscribe naturally (or conventionally) expressive gestures, movement, and voices of actors; the general avoidance of the expressive facial close-up in Rossellini’s neorealist films; and the lengths to which Antonioni and Tarkovsky (and their cinematographers and production designers) have gone to alter the natural, or found, color of objects and places in making films, including painting (or repainting) natural landscapes and parts of cityscapes (in Blow-Up and Red Desert) and using lens filters and postproduction effects (in Stalker and The Sacrifice).

Crucially, the transformative use of such expressively “radioactive” materials, which may impact all that surrounds them in a film in both expected and unexpected ways, as a means to larger aesthetic ends, may not only involve their suppression, reduction, or substantial modification; it may also entail their pronounced, highly intentional amplification. Thus, in the films of Dreyer and Cassavetes the unquestionable affective power of the human face in close-up (stressed in the writings of Balázs, Eisenstein, Deleuze, and many other theorists) is not minimized through avoidance but creatively maximized. The same may be said in relation to the inherent beauty and sublimity of natural landscapes featured in the films of Ford, Herzog, and Malick. Such instances allow and encourage us, as students of the medium and its art, to also stress the potentially positive aesthetic aspects of giving relatively freer rein to the natural expressivity of constitutive profilmic materials captured in their filming/recording, in relation to the total design of a film world (including its fictional characters and events, spatial and temporal structures, and reflexive and thematic meanings). Sometimes this occurs at the relative expense of narrative considerations and may be in (productive) dialectical tension or conflict with narrative and other formal and artistic elements.

In sum, and to return to our main focus, apart from its potential second-order, artistic meanings and uses, and whether it is stimulated mainly by the formal or medial properties and techniques of cinema or by the representational (mimetic) contents of images, any particular instance of sensory-affective feeling tends to be transient in a film’s unfolding, either momentary or quite short-lived. Such affect may be detached (in principle) from the fictional story-world of a film with which it is usually, and more or less loosely or integrally, combined. The phenomenon in question is a familiar one: it is readily apparent from viewing, and being affected by, certain images, or sequences in relative isolation—when, for instance, we flick through cable television channels and view bits and pieces of several films—while knowing little, perhaps nothing, about their characters and stories. Or, perhaps more interestingly, it is revealed in one’s notable affective responses to film previews when, again, as viewers we have often little or no narrative or dramatic context to draw on, apart from genre or similar expectations.

Finally, and most consequently, under this heading, and as taking any of the specific forms discussed, local sensory-affective expression always follows proximately from a direct, actual, external perception on the part of the viewer, as my designation “sensory” is intended to indicate. Indeed, its particular character is most prominent in contrast to that which is (or is also) intuited, imagined, or conceived in film experience. As such, this affective response is inherently audio visual and a cinematic product of “presentational form” (in Langer’s sense), far removed from what may be at work in relation to any linguistic (symbolic) mediation. It thus has little genuine counterpart in any form of literature, however poetically or imaginatively “imagistic.” Just the opposite may be argued, however, with respect to the next form of local cinematic affect, the cognitive-diegetic, which is in many respects comparable, at least, to the expression at work in novelistic literature and other narrative forms.

Cognitive-Diegetic Expression

I began the present reconsideration of cinematic affect and emotion by noting that what happens in, and in relation to, a story-world—as generated through the film viewer’s combined perceptual and imaginative engagement with fictional characters and the situations in which they find themselves—is often assumed to be the site of the most primary, important, and meaning-determinate affective interactions in and of a film. In everyday experience we are familiar with the conjunction of feeling and imagination in the narratives we construct and tell ourselves and each other in what can be considered a primary cognitive strategy for organizing our lives, apart, that is, from any special, purposefully created and formally presented fictional and artistic narratives—which, from this particular perspective, are but elaborate extensions in culturally instituted forms of the basic narrativizing propensity of the human mind (a propensity that, as Barthes has written, “is present at all times, in all places, in all societies”).29

Cognitive-diegetic affect is, then, basically the virtual film version of the emotive aspect or dimension of many and various kinds of life-situations in which people might find themselves. Such expression follows from our willing, fiction-accepting engagements with stories, together with their human or humanlike characters, actions, and situations. And it may occur in conjunction with either first- or third-person perceptual or imaginative perspectives. Of course, in contrast to real-life conversations with other people, when we may both imagine and feel the unusual events a friend recounts to us in the theater of our individual imaginations, and also distinct from the descriptions of life-situations found in works of literature, narrative films provide concrete and specific images and sounds to aid, supplement, or lead, but also in some ways to constrain, our already emotion-laden imaginations.30

Familiar forms of local, cognitive-diegetic emotion are generated through the capability of a film to virtually place the viewer in the temporal and spatial position of a character or even an inanimate object. Or, in contrast, it may follow from promptings in which we, as viewers, take up the position of an imaginary witness in the midst of the action in the perceptual and cognitive role of an unseen human, “ideal,” or “godlike” observer of story events. Not only through the point of view and movements of the camera, but through framing, mise-en-scène, and editing, as tied to narrative structure, we may seem to cross no-man’s-land “with” Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) and his men in Paths of Glory; slowly approach the ominous Bates house in Psycho “in the place of” Detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam); or glide through empty hospital corridors toward a ventilation system in Syndromes and a Century “as if” we are a phantom or percipient speck of dust. And, accordingly, we may be disposed to experience many distinct feelings by virtue of these literally represented but still partly imagined situations, insofar as we are willing to “enter” and become immersed in the represented story-world (however much this may also seem an automatic part of narrative film viewing).

Another, arguably distinct, form of cognitive-diegetic expression in cinema is emotion that accompanies the apprehension of certain represented situations or events independently of the above-noted dynamics of point of view or, for that matter, any considerations of the viewer imaginatively placing him- or herself in the psychological “shoes” of a character (or even object). Instead, as Carroll has argued, with recourse to his concept of emotional “prefocusing,” as the “raising of various preordained emotions,” this entails viewers’ simply taking part in an affectively charged, virtual reality, as reproductive of one with which he or she is already familiar (at least as a type of experience), either from ordinary life or the prior experience of other films (or both).31 These include the (now) clichéd situations and episodes of the on-again, off-again love affair and its emotional roller coaster, the frightening alone-in-the-home situation of defenseless (for the most part young female) victims of psychopaths, the inevitable denouement of a courage-testing mano a mano gunfight, and so on.

Indeed, and as Carroll’s numerous discussions of the general topic persuasively suggest, some genres privilege cognitive-diegetic expression more than others. In fact, it seems as if entire cinematic genres may be defined in large part by reference to the relative prominence of this type, as compared to expression that is clearly little more than sensory-affective. Melodrama, romance, some forms of comedy, and the classic western and gangster films are particularly rooted in cognitive-diegetic expression. Here desired audience responses in the form of so-called garden-variety emotions are aided and abetted by markedly realistic settings and actions, as opposed to more patently “unreal,” impossible, or fantastic ones (which may tend to inspire more detached or merely bemused attitudes). Such genres provide a familiar and stable representational playing field for vicarious participation in the emotional lives of characters, in contrast to many contemporary action, science-fiction, and disaster film blockbusters. In the latter cases, genuine affect is not, it would appear, dependent on highly implausible projections of oneself into such unlikely places and situations as earthquake zones, runaway trains, or battles with hostile aliens bent on destroying our planet. Rather, a great deal of affective intent and response in these latter sorts of film entertainments appears to be more a matter of relatively mindless and instantaneous visceral perceptual and bodily effects of the dynamic spectacle of movement, sound, and light (often enhanced through CGI technology), in one extreme manifestation of what Bordwell describes as “intensified continuity style” filmmaking.32 Here the sensory-affective at its most confrontational is at least coequal with the cognitive-diegetic (and potentially, at least, formal-artistic expression, to be addressed shortly). Indeed, there is little doubt that in some narrative films, characters, settings, and events provide little more than a pretext for the conveyance of perceptual novelties and thrills, wherein the current cinema quite consciously makes its closest approximation to amusement park rides,33 versus more imaginative or “vicarious” involvements.

Yet even the most special-effects- and shock-laden horror and action films also provide some role, still often a prominent one, for cognitive-diegetic affects (e.g., as involving narrative suspense, as well as perceptual shocks). The horror film, in particular, in both classic and more contemporary iterations, trades on the highly deliberate mixing of both modes of feeling content, either simultaneously or with one setting up the affective “payoff” of the other, as in, for example, Dario Argento’s giallo thrillers and John Carpenter’s Halloween (both key templates for the much-maligned “slasher” film subgenre). In these films and countless others the use of now-ubiquitous point-of-view editing and camera movement techniques provides for an imagination-based, perspectival identification and anticipation, coupled with more purely perceptual shocks and affects.

If sensory-affective expression begins and ends with certain, immediately given perceptual contents and more direct psychological stimulus and response, from the aesthetic standpoint of laying the foundation for prominent artistic figurations and exemplifications of various kinds in narrative cinema, cognitive-diegetic expression far surpasses the more elementary, relatively “mind-independent” form. While also necessarily grounded in what is presented to our organs of sight and hearing (coupled with whatever unconscious, constructional activities occur in connection with cinematic perception), it is the bridge that connects the film viewer’s capacities for comprehension of the representational contents of the film image with emotional contents and response. In fact, while most recent, philosophical analysts have concentrated on the link between constructed narrative situations and the elicitation of a limited range of standard, stock, or garden-variety emotions by filmmakers—of the ever-reliable kinds that are (now) expected by popular audiences—the import of their favored approach in terms of “cognitive-evaluative” or “situation-assessment” models is far more profound. For, in opening the door to the manifold ways in which films and their worlds may describe and represent social and psychological situations, and dramatic characters and their interests and motivations (in order to foreground and convey the affective dimensions of any of these) they may equally invite consideration of highly complex, often much more subtle, emotions. These take correspondingly complex, often uncertain, objects. And given that the “cognitive” and representational basis of such emotion in films is clearly part of their symbolic dimension, many of the artistic means and strategies for producing expression of this type, and particularly of its instances that are of greater aesthetic interest and value, are those symbolic functions and uses, and the world-making processes built on them, I have attempted to explain in the preceding chapters. In fact, a film world as a whole may be regarded as a feeling-facilitating “cognitive object.”

The strong link to representation and narrative is the main reason why instances of cognitive-diegetic expression tend to be longer lasting in their impacts than the typical shocks and surprises of the sensory-affective. Whereas the latter form of local affect is responsible for causing sudden intense blips on the seismographic recorder of conscious emotional response in film viewing, the former tends to produce plateaus and hollows of somewhat longer duration involving emotional highs and lows that typically extend through entire scenes or episodes of narrative development. The strongest, most characteristic form of this affect-type, however, tends to remain either scene- or episode-specific and, if relatively more enduring, still takes a film’s story-world (world-in) as its general object. Most important for our present purposes (and as also recognized by Tan), despite its great potential in this direction, such cognitively and narratively mediated expression still need not, and quite often does not, involve any implication or acknowledgment of a film qua artwork: according to which expression is valued insofar as, among other reasons, it is more singular to the specific intentions of film artists as realized in the medium and in an artistic style. However, whether having more novel or more familiar objects and causes, if and when such feeling contents are also conjoined with some significant attention on the part of the filmmaker (in the process of creation), and especially of the film viewer (in experiencing the work), to the artistic form (and style) that presents and occasions it and its interpreted meanings, cognitive-diegetic expression takes on a more distinctly aesthetic character. For it then consciously involves not only the represented “what” but the formal and stylistic “how” and the artistic and intentional “why” of a representation, situation, or technique.

Formal-Artistic Expression

Art is achieved when the emotion is the product of an intention successfully (i.e. convincingly) executed and not just a reality incidentally impressive in itself.

—Jean Mitry

The idea that expressive properties of artworks are associated primarily, and as a class, with aspects of created and perceived form, as distinct from content, is a traditional one (certainly traceable as far back as Kant’s aesthetics). In critiquing the idea that art is a more or less direct reproduction of “our inner life, of our affections and emotions,” Cassirer writes trenchantly that art “is indeed expressive, but it cannot be expressive without being formative.”34 With specific application to cinema the same basic notion is articulated by Mitry, who argues that “it is only through the agency of a form that the audience can be led to discover the thoughts of the filmmaker, to share his feelings and emotions.”35

A film’s localized and formative expression may be contrasted with both immediate sensory-affective stimulation and cognitive-diegetic emotion as exclusively tied to, or caused by, fictional story events and characters. This expression arises in consequence (more or less direct) of some attention to specific features of a cinematic work as a work rather than as a purely perceptual reaction to a filmic sight or sound or an imagination and thought-aided connection to the fictional reality a film establishes (alone). At the same time, however, formal-artistic expression frequently works through either or both of these in representational and narrative cinema. Indeed, the affective cinematic features in question are “formal” not in the sense of being free from any representational content, for instance, since it is precisely that which is represented that is also somehow creatively formed and structured in a way more or less unique to each film. As such, and unlike the affect associated with the mimetic cinematic representation of inherently highly expressive (i.e., profilmic) realities, this type of feeling content is wholly “made” by filmmakers when the work is made, as opposed to channeled (or “borrowed,” as it were), and is only realized through requisite viewer attention. As Mitry holds, its instances are frequently governed by artistic intentions related to the creative interpretation of a subject, or some aspect of recognizable reality, that uses and surpasses cinematographic representation and, today, video-digital representation and its basic psychological effects, and where such interpretation includes an emotional or affective stance. Thus, it is the product or effect of participation with a film’s artistic presentation, as opposed to only its dimension of representation and, a fortiori, situations thrown up by the story-world.

A principal source or object of this third basic form of local expression may be stylistic features and what I have described as a film’s prominent “world-markers” in their more perceptually and affectively transient aspects. For instance, it may reside in the way that a given scene is staged, a shot framed, an object lit, or the tone of a voice-over narration. Or it may involve a film’s selection and presentation of the aforementioned inherently expressive realities, if and when a film appropriates these to its own artistic ends, as recognized and appreciated by the viewer, who is moved accordingly. The full artistic and emotional effect of Psycho’s landmark shower scene, for example, is some complex, superbly orchestrated amalgam of sensory-affective, cognitive-diegetic, and formal-artistic expression.36 This last may stem not only from more abstract properties of film form but from exemplifications of such properties that are productive of metaphors, allusions, or other external associations as these are grasped by viewers (and with which the images of Marion Crane’s murder and aftermath are replete). Thus a film may provide “a richly symbolic commentary on the modern world as a public swamp in which human feelings and passions are flushed down the drain,” as Andrew Sarris observed about Psycho, referring to both the shower scene and the film’s final image.37 Through its maker’s creative, formal, and artistic transformations of the preexisting and known, a film may “speak” in highly affective fashion, not only about the imagined or imaginary lives of characters in some “other” place and world on the diegetic plane but to something about our lives and experience as viewers, or life in general—and do so in highly affective, feeling-generating fashion.

For viewers attentive to it (and possessing the requisite extrawork knowledge and experience), the full and no doubt intended emotional power of Alex’s (Malcolm McDowell’s) assault on the writer and his wife in A Clockwork Orange, played out to the accompaniment of “Singin’ in the Rain,” derives not only from the visual, photocinematic depiction of brutal violence inflicted by one person on others, nor from the specific narrative context in which it occurs, nor from an identification with the characters who are the victims of the senseless attack. The emotional power of this sequence arises also, and emphatically, as a result of the familiar, comforting, and feel-good extrawork associations of the song—and the Hollywood musical of which it is a part—as unexpectedly and “perversely” paired with this represented action in allusive fashion. As manifesting a provocative, confrontational artistic choice on the part of the film and director, the resulting “cognitive dissonance” and affective tension or frisson translates (in the manner of Tan’s A-emotion) into feelings about the film as a work and an experience (whether positive or negative). Although “Singin’ in the Rain” is a diegetic feature of the fictional world-in the film, through the aegis of the viewer’s affective as well as intellectual response to the constructed sound-image presentation (which it both allows for and encourages), it notably transcends this narrative-fictional reality, prompting reflection on the artistic world-of the film—its intentions, and its extranarrative thematic, satirical, allusive, and cinematically reflexive meanings.

To reiterate, whatever specific form it may take, what chiefly distinguishes this type of affective expression is that a particular feeling either is simultaneous with, or, in some cases prompted by, a recognition pertaining to something specific about the cinematic work as a work. While most frequently very closely conjoined with it, such feeling, it also bears repeating, may on occasion bypass the fictional world-in (and imaginative engagements with it) or, at least, not depend on it integrally. Nor is it to be (solely) attributed to the iconicity of the cinematic medium, that is, as simply the affective result of visually reproduced objects, still or in motion, or its power to stimulate the senses and emotions through any other more direct means. Rather, it entails the recognition and experience of potentially any of a cinematic work’s individual symbolic-aesthetic exemplifications (as previously described), together with what Deleuze aptly refers to as “attentive” as opposed to merely “habitual” recognition and engagement with a film work.38

While it may yet have the same general perceptual source or cognitive object as that of an instance of sensory-affective or cognitive-diegetic expression—for example, a deep-focus composition, a dramatic event, the movement of a character or the camera, the color scheme of an interior—formal-artistic expression is disclosed to a different manner or mode of attention, as if on another “wavelength”—an aesthetic one, in this case—of affective reception and awareness. Here, then, is one affective equivalent, and often consequence, of the aforementioned experiential duality characterizing cinematic presentation, wherein the viewer may attend to the film image both as a representational window on its represented subject and story and as a meaning- and intention-bearing construction in simultaneous, or alternating, fashion. As an affective component of the symbolic-aesthetic multiplicity, complexity, and density of artworks discussed previously, such expression is another hallmark of artistically motivated and successful films. And, in turn, their full significance and value as art depend on how skillfully (in all of the details and complexity of the general task at hand) this mode of affect is achieved.

Such formal-artistic expression, even though still “local” within a film world, is generally more durable than the other two types discussed, which tend in many cases to diminish in emotive power and are relatively less able to survive repeated viewings of a film. As viewers, we may often be less emotionally moved in relation to the characters and story (of which we know the end results) of Psycho, or almost any other film, after having seen it a number of times. Or, and perhaps especially, we may not be affectively jolted to nearly the same degree (if at all) by particular filmic effects, minus the powerful element of perceptual and dramatic novelty, shock, and surprise, when seeing a film again (and again). Simultaneously, however, and through the acquisition of all sorts of information related to a film and its making, for instance, we may become ever more aware and attentive to aspects of how a now-familiar story and plot are presented, a shot composed, or a line delivered. And, as a consequence, we may become more sensitive to the relevant affects and emotions they may be intended to generate and why. That is, we become attuned to their meanings and functions in the context of the meaning and the felt and interpreted intentions of the cinematic work as a whole (including what Goodman refers to as the “cognitive function” of feeling in art as a route to knowledge about the world). All of this clearly crosses over into the realm of aesthetic experience and appreciation.

In sum, this tripartite classification of local filmic expression and affect is a tool of analysis, not a suggested recipe for artistic filmmaking. Nor, for that matter, is it always visible, as such, in the sensory, narrative, and artistic unity of specific films. The reality is that these types continually overlap and merge with one another, sometimes cooperating and sometimes not, to elicit the range of powerful emotions that, as all concede, characterizes most if not all fiction films. Thus, whatever feeling the final, close-up image-sequence of the face of Bob Hoskins, playing gangster-cum-businessman Harold Shand in John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday, may instinctively or “naturally” prompt in being an iconic image of a human being whom we may immediately (perceptually) recognize to be in certain emotional states (as an instance of sensory-affective expression)—our response is also, one must suppose, inseparably mixed with feelings arising in relation to the understood narrative and dramatic situation of which the face and its expressions are a part (i.e., cognitive-diegetic expression). In this case the clearly inexorable, ironic-tragic situation of Shand, who has literally just fallen into the hands of IRA assassins, after having previously launched an unwinnable “gang war” on the organization (fig. 6.2). Such emotional projection on the part of viewers may well entail a feeling of “poetic justice,” given Shand’s situation, or an empathetic or sympathetic identification with the character (however violent and immoral his previous behavior). But this story-rooted emotional identification and projection is also likely combined, or concurrent with, the viewer’s by-this-point developed feelings toward the film work of which this culminating close-up is a major part, in the form of a formal-artistic expression and exemplification tied to the film’s meaning(s) and purposes as a work.

The Long Good Friday is particularly instructive in this latter respect, since the cinematic close-up is held for an unconventionally long period, far more than is required for the purposes of conveying basic narrative information and for a good deal longer than any other close-up in the film, as well as most close-ups in most narrative films.39 This duration emphasizes the close-up image’s artistically expressive intent as tied to a particular cinematic technique. In terms of Bordwell’s theory of film narration and viewing, the presence of the close-up and the feelings it generates here are readily perceived as the product of an “artistic motivation” on the part of the film and its maker(s) translating into an “aesthetic perception” on the part of the viewer. The latter provides its own “added” affective contribution to the sequence’s experience (that is, in addition to what might be felt apart from it).40 The viewer is in effect asked to appreciate and contemplate the alternately bemused, frightened, and resigned face of Hoskins/Shand, not at the expense of narrative or fictional comprehension and empathy (or antipathy) driven immersion, however, but, also and simultaneously, as a symbolic and artistic construction and intention. Indeed, here as elsewhere in cinema there is a certain creative fusion of expressive modes, possible in perhaps no other art, in which feeling is at once conveyed, heightened, and visually articulated to artistically meaningful ends.

FIGURE 6.2 Different forms of local film-world affect converge on the face in Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday.

CINEMATIC ENGAGEMENT AND IMMERSION: LOCAL SOURCES

The less literal (i.e., physical) of the two meanings of the word immersion pertains to a pronounced mental attention, concentration, or absorption in relation to an object or event. While immersion in the world of a film is largely mental and virtual, as distinct from physical, it is as “real” for the viewer as many other conscious episodes of perceiving, feeling, imagining, or remembering. Moreover, film viewers may experience actual bodily effects before the screen, as much as entertain cognitive and emotional ones—for example, physical anxiety, warm glows, cold sweats, fright, intense pleasure, anger, disgust, and so forth. For these reasons, among others, while a host of synonymous terms may be used for describing absorptive cinematic experience, immersion (with its physical connotations) remains an apt term to capture the experiential sum of the perceptual, imaginative, and affective acts of a viewer “entering” into a film, with the range of (potential) consequences for both mind and body that ensue. As our discussion and the specific examples cited make clear, each local form of affect, but particularly the cognitive-diegetic and sensory-affective, can be seen to correspond to, and be partly responsible for, distinctive forms or aspects of cinematic immersion. Such instances of immersion are, in turn, equally “local,” in the present sense of often being relatively temporary in terms of their psychological holds on viewers.

Granted a prominent place in contemporary affect-centered or “sensuous,”41 film theory, what I have termed sensory-affective engagement involves the viewer’s becoming notably absorbed in a film’s perceptual and affective experience on a basis that is more immediate and primary than one reliant on any aspect of the fictional-representational and narrative dimension. With the now more or less continuous development of technical virtuosity in special effects and CGI, as well as 3-D viewing, a good portion of contemporary narrative cinema has been given over to (would-be) immersive, sensory spectacle, for which there is clearly a mass appetite. However, and as suggested by Tom Gunning’s influential conception of the early “cinema of attractions,” as rooted in the creation of a filmic spectacle that privileges “exhibitionism” over “voyeurism” (which puts the viewer in the place of witness to the lives and actions of characters in a contained diegetic space of drama), this is by no means only a contemporary phenomenon, necessarily associated with the latest digital technology or public demand.42 Yet, and especially for a contemporary audience highly familiar with moving-image experiences of all kinds, such immersion in pure (or purer) spectacle may often be (as one may assume) local and transient in viewer consciousness. For it relies on a more immediate and largely present-tense mode of viewer attention, which is to some degree in perceptual-cognitive competition with the strong pull of relatively less immediate and more reflective narrative construction, comprehension, and absorption (as also rooted in memory and anticipation), with which it oscillates.

A more specifically representation- or story-directed immersion in films is partly accounted for, and assumed in, the theories of film-viewer emotions discussed earlier and are to be found in numerous semiotic, psychoanalytic and narratological accounts of cinema focused on one or another of its aspects. Such psychological immersion in the fictional world-in a film operates through pronounced imaginative and empathetic or sympathetic relation to aspects of its represented reality, as distinct from explicit attention to the sensory and formal-artistic means by which this reality is constructed and exhibited (or a film’s high-order meanings). Such a relationship to a film, bound to acts of imagination as more direct perception, may, like the proposed category of local expression, also appropriately be termed cognitive-diegetic (or, depending upon its objects, narrative-fictional) immersion.

In attempting to describe a particular mode of artistic experience that he terms experiencing a work “from within” (which has a strong “aspect of illusion”) rather than “from without,” R. K. Elliott writes of how a viewer of Pierre Bonnard’s Nude Before a Mirror (1915) may experience the sight of the woman depicted (in this case the painter’s wife) in the way that the painter has. In observing this domestic scene, the viewer may feel something of the painter’s expressed tenderness toward his subject, “as if he has assumed not only the artist’s visual field but his very glance, and is gazing upon the same world with the same heart and eyes.”43 For Elliot this type of attention, focused on the work’s represented scene, entails possibly being simultaneously less focused on formal aspects of the painting as a constructed image (i.e., the “how” as opposed to only the “what” of the representation). Moreover, the feeling conveyed by, or pertaining to, the latter sort of “from without” attention may well be notably different in nature from that provided by an imaginative “from-within” engagement with representation (as founded on “an imaginative extension and modification of what is actually seen”).

Elliott is right to maintain with respect to painting, among other arts, that while an immersive and emotional experience of this kind—wherein the work ceases to be “an object in the percipient’s visual field” and becomes “itself the visual field . . . experienced as if the objects were real” (163)—may occur at any juncture. But given its strongly individual-specific, or subjective, character and variability, it still most often and typically follows the work’s own lead. Through its form, style, or genre, a work creates a cognizable stage, space, or “frame” for such an imaginative, and potentially more subjectively “intimate,” entrance, identification, and participation with represented realities. In a film such engagement with represented objects and situations may be encouraged through composition and framing (as also in painting), through staging and dialogue (as in live theater), and through all sorts of narrative and plot devices (following the form of literature), as well as through musical and other auditory cues. But further, and unique to cinema, it may be fostered through camera movement and editing, and the particularly cinematic coupling of sound (including music) and image. Like local cinematic expression, such immersion in the represented world-in films is also often localized and temporary in nature, as Elliott argues with reference to art and literature in general.44

According to the familiar concepts of “aesthetic distance” and objectivity, such imaginative, representation-centered viewing (or reading or listening) amounting to immersion, has been sometimes seen as necessarily antithetical to the proper experience and appreciation of artworks qua artworks.45 But far from challenging the potential aesthetic relevance of occurrences of highly imaginative and emotional engagement, via such “identification” with a character, object, or situation, the present account of film works and worlds readily acknowledges its contribution. Transposed to cinema, it is in full agreement with Elliott’s claim (contra the “objectivist” conception of aesthetic experience and appreciation rooted in “psychic distance”) that while “not sufficient from the aesthetic point of view,”46 this sort of highly subjective, imagination-enabled engagement may still be of clear aesthetic and interpretative significance with respect to some film worlds, and parts of them, at some times. Certainly, many film worlds may encourage such an emotive, cognitive-diegetic pathway to immersion in their alternative reality as part of general artistic designs intended by their makers, even if, in other cases, such experiences on the part of viewers may have little to do with the filmmaker’s intentions or what may be reasonably considered the artistic meaning and function of a film. Generally, the fact that viewers can and do become engaged in films in these ways (more or less exclusively) does not preclude other, sometimes equally (if not more) profound, and aesthetically focused, immersive engagements with films and their worlds—ones, that is to say, that move notably beyond the represented world-in as an imaginary reality rather than being confined to it.

Both of these forms of cinematic immersion, sensory-affective and cognitive-diegetic, are important and interesting in their own right, as evidenced by the amount of attention they have received from contemporary film theorists and philosophers of film, as well as cinema historians focused on changing means of film exhibition and projection. Yet our greater concern from the perspective of a full aesthetic account of film worlds is with a more holistic, synthetic, often more persistent—yet still dynamic—immersion in film viewing. Owing to its sources and effects, it may be considered distinctly (or “first-order”) artistic and aesthetic in nature. If a cinematic work of art as experienced, coupled with the world it brings into being, is an integrated symbolic and affective whole, it must on some level compel the attention and capture the imaginations of viewers as such. And cinematic immersion conceived as nothing less than film-world entry and aesthetic participation, as distinct from primarily perceptual immersion in audiovisual spectacle, or imaginative absorption in a cinematic story-world (or part of it) alone or exclusively, is closely connected to the last type of cinematic affect in our present scheme: global film-world expression, or the created and experienced “world-feeling” of films.