LESLEY WOOD

How do we best understand the recent global cycles of contention? This chapter analyzes the first 206 events within Canada’s 2012–2013 indigenous-led mobilization Idle No More as represented by social media and indigenous writing and in the mainstream press. To understand how this wave of protest spread, the chapter compares two approaches: the first is George Katsiaficas’ eros effect, and the second is Sidney Tarrow’s work on diffusion that draws on a “dynamics of contention” approach to social movements. Neither approach adequately explains variation in the participation and spread of these waves. However, an analysis of stories of emotion enables us to incorporate Katsiaficas’ emphasis on pleasure and solidarity into Tarrow’s emphasis on relational patterns of action. In this way, we are better able to understand both how and why waves of protest unfold in particular ways.

The drummers pounded out a steady heartbeat as the young woman looked at her friend, grinned, and grabbed her hand. Heads held high, the two joined the end of the chain of people snaking past them in the food court in the Sudbury, Ontario, shopping mall. The event they joined was one of seventy-nine that took place that day as part of the wave of protest known as Idle No More.

The rapid and euphoric spread of the indigenous-led mobilization (with its unique symbols, frames, and tactics) in 2012 coincided with many similar protest waves occurring around the same time. How should we understand such waves?1 In what follows, I provide an account of Idle No More that challenges Katsiaficas’ dismissal of social movement theory by showing how the latter provides important insights into the way that waves of protest operate. To be sure, I believe that Katsiaficas is right to challenge the tendency for many social movement theorists to assume that movement participation is purely a question of rational action, as well as their tendency to overlook the question of why waves of protest emerge at given moments. Despite these shortcomings, I believe that Sidney Tarrow’s analysis of protest waves offers insight into how waves of protest unfold. Such information is not only of interest to academics, but also to activists trying to understand how best to spread and intensify protest. In isolation, however, neither Katsiaficas’ account of the eros effect nor studies focused on the dynamics of contention can fully explain why and how mobilizations like Idle No More can and do vary across time and space.

I must acknowledge that I am a white settler writing on land that has been a home and hunting grounds to many peoples, including the Haudenosaunee, Wendat, and always the Mississaugas of the New Credit. I should also situate myself as a scholar. I am a sociologist who analyzes the micro and macro interactions that influence social movements. My work asks why social movements vary in their form and tactics and what influences their outcomes. As an activist, I want to know how to make movements more effective. My framework draws both from the contentious politics framework of Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow and the narrative sociology of Francesca Polletta. The ideas presented in this chapter reflect this disciplinary background.

Idle No More was initiated by four women (three indigenous, one nonindigenous) in Saskatchewan at the end of October 2012. On November 17, these activists organized their first teach-in about two omnibus budget bills then before the House. The first, C-38, would make it easier to sell off indigenous land to mining and petroleum interests.2 The second, C-45, would remove provisions for the environmental protection of waterways, which were seen as barriers to pipeline development. As per usual, the government had not consulted indigenous communities before the bills were proposed. Anger mounted. On December 6, Assembly of First Nations (AFN) chiefs marched on Parliament Hill with the aim of addressing the House of Commons about the bills.

Called by the Idle No More organizers, the first national day of action on December 10, 2012 saw fifteen rallies and marches across the country. In Edmonton, 1,500 protestors marched, held a pipe ceremony, spoke out, and sang against the bills while acting in solidarity with the Beaver Lake Cree Nation fighting ongoing tar sands developments in Northern Alberta. The following day, Chief Theresa Spence of Attawapiskat began a hunger strike outside the federal government buildings in Ottawa to demand that greater respect and attention be paid to indigenous communities and their needs.3 At this point, both mainstream and social media coverage of the movement increased. On December 13, members of the Samson Cree Nation blockaded Highway 2A in Alberta. Their action was followed by two protests in the Maritimes. Although Idle No More protests were gaining momentum, the federal government passed the second of the two bills, Bill C-45, on December 14, 2012.

Despite this setback, the mobilization continued to gain momentum. Its objectives expanded from repealing the omnibus bills to include “the stabilization of emergency situations in First Nations communities accompanied by an honest collaborative approach to addressing issues relating to Indigenous communities and self-sustainability, land, education, housing, healthcare, among others,” and “a commitment to a mutually beneficial nation-to-nation relationship between Canada, First Nations (status and non-status), Inuit and Metis communities based on the spirit and intent of treaties and a recognition of inherent and shared rights and responsibilities as equal and unique partners. A large part of this includes an end to the unilateral legislative and policy process Canadian governments have favoured to amend the Indian Act.”4

On December 15, there were two Idle No More rallies—one in North Battleford, Saskatchewan, and one in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Additionally, band members from at least three First Nations in Manitoba—including Sandy Bay, Long Plain, and Swan Lake—blocked the Trans-Canada Highway, while members of the Frog Lake Band in Alberta blocked Highway 28. In the first use of a tactic that would come to symbolize the movement, five hundred indigenous people and supporters in Regina Saskatchewan organized the first flash mob round dance in the Cornwall Square Mall on December 17. Accompanied by singing and drumming, round dances are traditional indigenous circle dances used to bring communities together.5 That same day, a round dance took place at the Enoch Arena in Enoch, Alberta. One video shot at the Regina round dance flash mob has (as of 2015) been viewed more than 18,000 times, and shared 136 times—the vast majority in the two weeks following the event.6

The following day witnessed a flash mob round dance with hundreds of participants in the West Edmonton Mall. The event was also filmed and shared widely. One clip, uploaded by Paula E. Kirman, has been viewed over 95,000 times (as of 2015) and shared 547 times.7 In the subsequent seven days, there were more than 120 events affiliated with the movement, including 39 round dances and 12 blockades. To track these events, I have used an event catalog with data pertaining to the first two hundred events to take place during the two months (November and December 2012) following the rise of Idle No More.8

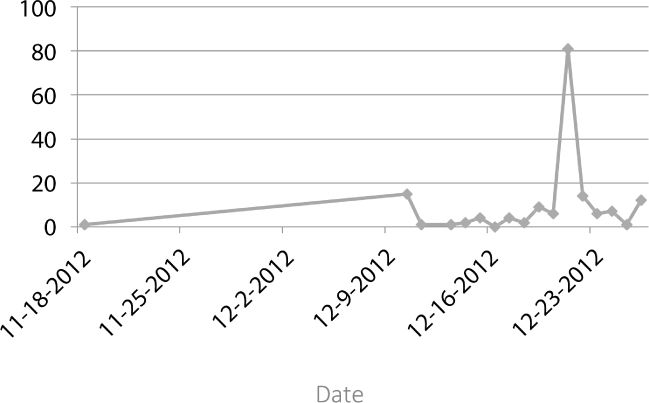

The videos shot at round dances and posted on YouTube and other sites inspired imitation. On December 19, there were eleven more events. These included the first round dance in Ontario and the first event in the United States. Two days later, the second National Day of Action on December 21, 2012, included at least seventy-nine events, including twenty-two round dances (thirteen of which were in malls) and eight blockades.9 After this point, protesters across the country mobilized half a dozen events each day until the end of 2012. Another spike in mobilization occurred on January 5, 2013, and again on January 11, 2013.

While the overall shape of the protest wave is easy to discern, it is important to note the variations in levels of participation, diversity of participants, organizational form, and protest tactics used in different regions and at different moments. The excitement faded more quickly in some places than in others. By March 2013, activists in many places had shifted away from street protests and round dances toward the slower work of building new campaigns, networks, and institutions. Sometimes, they identified as Idle No More in this work while, at other times, they did not. Meanwhile, some former participants demobilized entirely.

Figure 12.1. Number of Idle No More Protests per day, November–December, 2012.

While this is a typical pattern for a protest wave, the Idle No More wave has some particular features. Initial data concerning the overall shape of protest waves associated with Idle No More, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter show differences with respect to their duration, the sharpness of their rise and fall, and the number of their peaks.10 While all three movements accelerated rapidly, when compared with Black Lives Matter (where spikes correspond with police brutality and court decisions) and Occupy (where spikes correspond with eviction attempts), Idle No More slows more gradually, with spikes corresponding to movement-directed days of action.

Since the emergence of the wave of protest associated with the Arab Spring, indignados, and Occupy Wall Street, there has been a flood of studies concerned with waves of protest, diffusion, and cycles of struggle.11 Such waves are generally understood in one of three ways. The first approach, reflected in this book, emphasizes the eros effect. The second, favored by autonomous Marxists, frames waves as a manifestation of the “circulation of struggle.”12 The third approach, used by social movement theorists like myself, ties waves of protest to relational patterns of diffusion, which are themselves a part of broader political processes. Considering these various approaches, Katsiaficas provides the following summary:

The Marxist notion of the circulation of struggle and the concept of diffusion are valuable because they show that struggles impact each other. Diffusion—what Samuel Huntington called “snowballing”—can help us to trace how one thing causes another, which causes another in turn. But neither theory allows us to comprehend the simultaneity of struggles that occurs during moments of the Eros effect. It’s not just causes, not just A plus B equals C. Events erupt simultaneously at multiple points and mutually amplify each other. They produce feedback loops with multiple iterations. To put it in terms of a mathematical analysis, we could say that diffusion and the circulation of struggles describe the process of movement development geometrically. The Eros effect describes these same developments in terms of calculus.13

In opposition to this characterization, I argue that a relational analysis of diffusion can usefully be integrated with the emotional and psychoanalytic elements of the eros effect. A relational approach tracks the micro-interactions of communication, exchange, competition, and collaboration among activists. Not only does such an approach provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of movement development, it also reflects the perspective of the activists themselves and can help to explain variation within waves of protest like Idle No More.

The event catalog data presently under consideration map the emergence of the Idle No More wave, which became visible on account of the increasing number of protests, bigger events, increased media coverage, and the addition of new participants and locations. Nevertheless, the question remains: How do we understand this wave? If we begin with the participants’ own perspectives, we hear stories like the one recounted by Lesley Bellau, an Anishinaabe woman from Garden River First Nations, who described Idle No More using the Anishinabek word Pauwauwaein. Bellau cites indigenous legal scholar John Borrows, explaining that this term is best understood to mean “a revelation, an awakening, a vision that gives understanding to matters that were once previously obscure.” She argues, “something extremely significant happened during the months of December 2012 and January 2013. It was a time of great action, of a great collective voice that rose together to work toward resistance, decolonization, cultural revival, and to hold hands within a new and possible hope that was only seen in fragments and small and scattered pieces before this.”14

Such a description appears to coincide with the insights of settler theorists of both the eros effect and of relational analysis, which both aim to explain the sudden expansion of protest activity and interaction. Drawing on Herbert Marcuse’s psychoanalytic dialectics to understand why such waves emerge, Katsiaficas attributes them to the eros effect, which he describes as “the massive awakening of the instinctual human need for justice and for freedom.”15 In such moments, self-interest is translated into universal interest; it signals a rupture in the status quo and a disruption of social control.16 For Katsiaficas, the eros effect is the trigger for the negation of established patterns of interaction and the creation of new (and better) ones. “During moments of the eros effect, popular movements not only imagine a new way of life and a different social reality but millions of people live according to transformed norms, values and beliefs.”17 Such claims are rooted in the observations advanced by Marcuse, who connected the eruption of protest to changes in the social structure, which in turn shifted the “instinctual structure” and thus increased inner antagonisms and loosened traditional mental ties.18 For his part (and though they seem to have more in common with social movement theory’s analysis of diffusion), Katsiaficas does not dismiss factors like the spread of television in his analysis of the 1968 wave of protest.19 However, unlike in analyses focused on diffusion, he links the effects of those factors to an accumulation of “libidinal forces,” which prompt the development of new formations before ultimately becoming “dynamite.”20

Approaching the problem from a different perspective, social movement theorist Sidney Tarrow describes a “cycle of contention” as a “phase of heightened conflict across the social system” involving: “rapid diffusion of collective action from more mobilized to less mobilized sectors, a rapid pace of innovation in the forms of contention employed, the creation of new or transformed collective action frames, a combination of organized and unorganized participation, and sequences of intensified information flow and interaction between challengers and authorities.”21 Having identified the dynamics that characterize the cycle of contention, political process and (later) dynamics of contention theorists work to understand variations in contention across time and space. The political process approach emerged partly in reaction to psychological explanations of collective behavior, which characterized protest as pathological.22 In contrast, political process theorists emphasize the rational, relational, and patterned nature of political protest. Using this framework, Tarrow’s definition of the cycle of contention highlights the temporary nature of a wave—its content of conflict, the social interactions that underlie the rising and falling levels of contention, and the sub-processes of diffusion, brokerage, and innovation.23 Such analysis brackets psychological dynamics, which are considered to be outside the realm of analysis. In the late 1990s, political process theorists increasingly looked for recurrent processes and mechanisms within dynamics of contention and began to unpack protest cycles in more detail. Tarrow and his collaborators then pointed out how the acceleration of protest cycles can lead to “scale shift,” a phenomenon in which mobilization transcends its local arena to become national or even transnational.24 In this way, “localized action spawns broader contention when information from the initial action reaches a distant group, which having defined itself as sufficiently similar to the initial insurgents (attribution of similarity), engages in similar action (emulation), and leads ultimately to coordinated action between the two sites.”25

Tarrow’s emphasis on the “attribution of similarity” or identification mechanism is in some ways homologous to elements associated with the eros effect. Both could be seen as facilitating brokerage (linkages between people) and diffusion (the spread of an idea or practice).26 While the eros effect leads people to act simultaneously due to a shared accumulation of libidinal forces, when potential participants/adopters see themselves and their context as similar to earlier participants/adopters, they “attribute similarity” and act. The presence or absence of this attribution of similarity explains whether innovations and mobilizations are likely to spread. However, this mechanism is seen as dependent on shared characteristics. As McAdam and Rucht argue, “All instances of diffusion depend on a minimal identification of an adopter with a transmitter.”27 Moreover, attribution of similarity is facilitated between transmitters and receivers if they share a common institutional locus as well as adherents from the same strata and a common language.28 However, the precise means by which people actually attribute similarity remains hidden since the dynamics of contention approach brackets activists’ subjectivities. As a result, the discussion of the feelings that enliven both Bellau and Katsiaficas’ accounts is absent.

Clearly, waves of protest do not simply spread across space and time uniformly. Idle No More became visible in early December across Canada, but the response by local activists in different cities varied in three dimensions: temporal, tactical, and with respect to size.

Organizers of Idle No More protests in each city have the best sense of why the protests unfolded the way they did. However, this “insider’ knowledge remains relatively inaccessible to analysts concerned with mapping broader social patterns. Admittedly, relying on social media and mainstream media might overestimate the size of protests, might miss events that don’t use a particular frame or keyword, and/or might be unable to capture dynamics outside of “events.” However, these data do show variation within the wave of protest. How might we explain this variation? While dynamics of contention theorists see the explanation in the context (its political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and frames) and how these affect relational ties, Katsiaficas points toward the ways that particular moments trigger a widespread release of action.29

Table 12.1. Idle No More Protests in Four Cities, December 10–30, 2012

| Vancouver | Toronto | Halifax | Montreal | |

| 12/10/2012 | March/rally–200 | March/rally–50 | ||

| 12/14/2012 | March/rally 200 | |||

| 12/20/2012 | Blockade/march–40 | |||

| 12/21/2012 | Rally–500 | Round dance–500 | News conference and panel 200 | Round dance |

| 12/22/2012 | Round dance in mall 200 | |||

| 12/23/2012 | Rally 400 + Round dance in mall–200 | |||

| 12/24/2012 | Round dance in mall near Montreal–600 | |||

| 12/26/2012 | Round dance–100 | |||

| 12/28/2012 | Round dance | |||

| 12/30/2012 | Round dance in mall 250 |

With the onset of Idle No More, why did activists in Vancouver and Toronto mobilize earlier than those in Montreal and Halifax? While recognizing that protest activity is only the tip of the movement iceberg,30 examining the ways the two approaches consider the timing of mobilization can be useful in illuminating their differences and angles. Dynamics of contention theorists explain temporal variation by looking at the relational context and perceptions of actors in a particular political regime (political opportunities and threats), available mobilizing structures, resources, and frames.31 Regimes can facilitate mobilization when influential or controversial decisions are made or when the ruling regime is itself divided, unstable, or unusually consultative. Under such conditions, activists may perceive an opportunity. Such contexts are therefore associated with increased contention, increased alliances between challengers and dissident elites, and increased success by challengers.32 In the case of the omnibus bills that prompted the explosion of Idle No More, activists in different cities shared the perception of an opportunity even after the bills had passed due to the increased attention to the movement by media and political authorities. However, differences in mobilizing structures and the resources available to activists in different cities helped to explain variations in mobilization. Each city varied in the size and organization of its local indigenous community. The cities with the largest aboriginal populations (Vancouver and Toronto) mobilized first.33 Each of these cities had indigenous organizations that mobilized on December 10 (the United Nations Human Rights Day). The larger communities and their mobilizing structures were resources to the activists. In addition, differing local contexts affected how the movement’s “frames” would be received. Frames (slogans, images, phrases) that activists use to explain their activity can resonate or fail to do so in a particular community, affecting the attribution of similarity and thus speeding or slowing mobilization. The Idle No More frame was likely interpreted differently in different communities, affecting the speed of mobilization. Mobilizing structures, resources and frames, and the way they help local activists to identify with the emergent movement can help to explain variation in the timing of mobilization; however, they say little about why an activist would identify with or join the Idle No More mobilization in the first place.

Katsiaficas might argue that such variations are minutiae. Indeed, he challenges the emphasis on resources in political process theory: “I hope to renew the tradition of thought that views human beings (not resources, organizations, and/or the ebb and flow of economic wealth) as central to the transformation of social reality.”34 Consequently, he “seeks to understand the nature of group behavior in moments of social crisis as attributes of human beings, not simply as caused by social conditions. My approach attempts to reintegrate the emotional and the rational at a level on which emotional and irrational are neither synonymous in their usages nor derogatory in their characterizations.”35 For Katsiaficas, the patterns of Idle No More would reflect a “logic of human action” giving expression to the subjectivities of human beings, rather than a reaction to shifting social conditions.36 Because his approach sees such logics as analogous to “historical-philosophical laws,” the role of existing organizations, resources, and frames would be viewed as ephemeral to the ebbs and flows of Idle No More.

Round dances are not new. Although they are most associated with Cree and Anishinabek culture, round dances have been enacted by indigenous people in different nations for generations. Nevertheless, round dances gained a new, contemporary appeal when carried out without warning as “flash mobs” recorded on video and shared on social media. In January 2013, Ojibwe spiritual leader David Courchene Jr. argued that these dances were significant. “There is a lot of excitement, I think, with young Aboriginal people. Round dances are sweeping across the country. I just hope that it’s kept in the spirit of the way that it was meant to be, which is to have peace and respect. People are looking for inspiration and guidance to a better world.”37

Although round dance flash mobs became the representative tactic of Idle No More, they weren’t used everywhere. Idle No More activists did not use them in Halifax, Quebec City, Chilliwack BC, or San Francisco. How might we understand this variation? Both political process and eros effect approaches connect waves of protest to the spread of tactics and symbols. Dynamics of contention theorists have shown how new or revitalized tactics or symbols can help to increase the level and spread of mobilization.38 Different cycles of contention become identified with innovative forms of action, which can leave elites at least temporarily uncertain regarding how to respond and thus opening political space for innovation and diffusion.39 Social movement theorists have tied different tactical innovations to different waves of protest. These include barricades during the 1848 revolutions, factory occupations following WWI and during the 1930s,40 sit-ins during the Civil Rights Movement,41 and, most recently, round dances during Idle No More. An action can affect the likelihood of subsequent actions in a number of ways. It can create occasions for action and alter material conditions in favor of mobilization by changing a group’s social organization, by altering beliefs, or by adding knowledge.42 However, activists in certain types of receiving contexts tend to be more able and willing to incorporate new tactics than others. Some work in the dynamics of contention tradition explains this variation by suggesting that spaces where potential adopters might deliberate about new tactics and their meaning and use are more likely to experiment with that tactic.43 While such an analysis of the Idle No More movement would require deeper qualitative research, such work directs us to look at how local activists interacted and made decisions to understand the variation in the use of round dances.

Because Katsiaficas tends to explore why rather than how waves of protest are shaped, less attention is paid to the way that a particular tactic would change the pattern of interaction. This is unlike the dynamics of contention research, which shows how tactical innovations like sit-ins, shantytowns, and black blocs have often accelerated and diversified mobilization and increased the scale of protest.44 While Katsiaficas explains how US activists in 1970 began blocking roads across the country, by his account “people didn’t block highways because they heard that people elsewhere in the country were doing it. It was just what people thought they should do.”45 The novelty or characteristics of a particular tactic are bracketed. Emphasizing a dialectical process, mobilization becomes a form of erotic action that clears “collective psychological blockages.” In this view, “episodes of the eros effect are regarded as the collective sublimation of the instinctual need for freedom.”46 This description resembles the way Idle No More activist Tanya Kappo, from Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation, Treaty 8 in Alberta, speaks about a round dance at the West Edmonton Mall in December 2012: “The power and energy that was there, it was like we were glowing, our people were glowing. For the first time, I saw a genuine sense of love for each other and for ourselves. Even if it was only momentary, it was powerful enough to awaken in them what needed to be woken up—a remembering of who we were, who we are.”47 Powerful descriptions like these are clearly pointing out key dimensions that help both to shape and explain waves of protest. The pleasure and intense emotion associated with the use of such tactics inspires imitation and mobilization. However, an absence of the eros effect is more mysterious. Why didn’t the activists in San Francisco who mobilized with Idle No More choose to round dance? Katsiaficas’ emphasis on love, connection, and spontaneity deemphasizes activist explanations of their strategy. Although he is underscoring a key dimension of protest, he has more difficulty accounting for variation within waves of protest.

The Idle No More data clearly show that some cities had larger and more frequent mobilizations than others. Of the four cities under review, both the largest and the greatest number of events took place in Vancouver. In contrast, Halifax had the fewest events and those in Montreal were smallest. Why? A dynamics of contention approach that emphasized the role of resources would suggest that larger cities are likely to have larger and more frequent mobilizations. This makes sense; however, it seems to contradict the fact that, although Halifax’s indigenous community is smaller than Montreal’s, there were more Idle No More events in the former city than in the latter. To understand why this might be the case, one could also look at the mobilizing structures (organizations and networks) in the different cities, their networks and history. As Katsiaficas has noted, existing organizations may sometimes attempt to control or squelch action. Discussing the Arab Spring protests, he recalled how, “unfortunately, existing progressive, left organizations often play regressive roles in these periods of time.”48 In addition to resources and mobilizing structures, the way that local histories affected the way local activists interpreted or responded to the frames of the mobilization might also affect the size and quantity of events. Such in-depth work is beyond the purview of this chapter, but it would yield deeper insight into how local histories, interactions, resources, and cultures affected the diffusion of Idle No More. Katsiaficas might agree with this last point. In his interview “Remembering May ’68,” he notes that the ability to access historical memories of struggle can facilitate and shape uprisings.49 This ability, it seems, varies from place to place, due to histories of struggle and oppression.

While Tarrow and other political process theorists explain variations in the size, tactics, and timing of protest activity as arising from relational processes and mechanisms, they bracket the psychological processes that might lead people to break from ordinary routines and pour into the streets. Because such analysts are wary of explanations that see protest as irrational or pathological, they have unintentionally reduced social action to a rational calculus in which risks and opportunities are weighed against each other. Aware of the limitations of this perspective, there have been attempts within the political process framework to incorporate emotion. Tarrow himself notes that the social and emotional processes of trust, attribution of similarity, and the opportunity for thinking creatively about tactics and action help to explain diffusion and brokerage.50 Similarly, both Sean Chabot and I have argued that deliberation can trigger cognitive and emotional reactions.51 However, we don’t offer much insight into why people feel joy and the sense of connection in these moments.

But, clearly, they do. Moreover, these feelings transform their actions and interpretations. Most sociologists and political scientists—including those working with dynamics of contention approaches—remain averse to explaining action as a product of psychic states. However, Francesca Polletta and others push the boundaries of this approach when they suggest that we can at least use the patterns of activist stories and storytelling to represent these states. In her article on storytelling in the Civil Rights Movement, Polletta quotes young civil rights activists explaining their activism using ambiguous phrases like “It was like a fever.”52 She found that, despite significant planning and organization, activists were likely to describe their movement as the result of something like spontaneous combustion. The participants’ insistence on spontaneity suggests that, for them, the term meant something other than that the sit-ins were unplanned. Digging deeper, Polletta finds that the activists’ shared emphasis on spontaneity signaled that they were independent from adult leadership, not being manipulated by communists, and were authentic and homegrown. The ambiguous stories that the students told were directed at least partly to themselves—and the telling of such stories helped to create a collective identity on behalf of which students took high-risk action. Activists used ambiguity to create a gap that kept causes and effects open and helped listeners to sympathize and identify with the movement.53 Their use of ambiguity seems to offer the space for the emotional and psychic connection that Katsiaficas describes. While Polletta argues that patterns in storytelling are culturally learned, she sees their structure as meaningful. Consequently, examining these stories in a systematic way can help to explain both why and how particular activists join waves of protest.

While the wave of protest has slowed, many are reflecting on the power of Idle No More and how it unfolded. Neither political process theory nor an analysis of the eros effect can fully explain the shape of the mobilization. Political process approaches may be able to explain why Idle No More spread more quickly and intensively to Vancouver and Toronto than to Montreal and Halifax. The variation in timing, form, and size clearly corresponds to differences in the size of indigenous communities and the development of existing activist infrastructure. However, this explanation cannot explain the feelings of intense connection and joy that fill the testimony of participants. While we may not be able to get at the psyche directly, we can—as Polletta suggests—get at the way these feelings are represented in story. By looking at the pauses and gaps in stories of joy and solidarity, we can build a more meaningful analysis of waves of protest, and better understand both why and how the world, sometimes, combusts.

1. My use of “waves of protest” is indebted to Sidney Tarrow’s “cycles of contention.” However, I prefer “waves of protest” because of its emphasis on diffusion.

2. For more on the background, see www.idlenomore.ca.

3. See Kind-nda-niimi Collective, The Winter We Danced: Voices from the Past, the Future, and the Idle No More Movement (Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring, 2014), 21–26.

4. Ibid., 22.

5. “Photos: Idle No More Protesters Stage Flash Mob at Regina Mall,” Leader-Post, December 18, 2012, http://www.leaderpost.com/news/regina/Photos+Idle+More+protesters+stage+flash+Regina+mall/7714700/story.html.

6. Smokey01Smoke, “Idle No More—Regina Round Dance Flash Mob,” December 17, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QA_Hn84SrCM.

7. Paula E. Kirman, “Idle No More—Round Dance Flash Mob at WEM in Edmonton,” December 18, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x2Nx4jUEZfc.

8. The event catalog is grounded in initial work done by researcher and journalist Tim Groves. In December 2012, he began to collect and map reports of all protest incidents affiliated with Idle No More, including media coverage and direct communication with organizers. He included event announcements, as well as subsequent reports. I have cleaned this data, checking links, removing duplicates, and finding additional verification of events. The data include 205 events from November and December 2012.

9. Blockades include information pickets of roads.

10. These waves are crudely compared using the Google trends data, which only capture the frequency of Google Searches for Idle No More, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter.

11. See, for instance, Donatella della Porta and Sidney Tarrow, “Interactive Diffusion: The Coevolution of Police and Protest Behavior with an Application to Transnational Contention,” Comparative Political Studies 45, no. 1 (2011): 119–152, doi: 10.1177/0010414011425665; Rebecca Kolins Givan, Kenneth M. Roberts, and Sarah A. Soule, eds., The Diffusion of Social Movements: Actors, Mechanisms, and Political Effects (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010); Lesley J. Wood, Direct Action, Deliberation, and Diffusion: Collective Action after the WTO Protests in Seattle (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012/2014).

12. See, for instance, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000); and Nick Dyer-Witheford, Cyber-Marx (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999).

13. George Katsiaficas, interviewed by AK Thompson, “Remembering May ’68: An Interview with George Katsiaficas,” Upping the Anti 6 (2008): n.p., http://uppingtheanti.org/journal/article/06-remembering-may-68.

14. Lesley Bellau, “Pauwauwaein: Idle No More to the Indigenous Nationhood Movement,” in The Winter We Danced, ed. Kind-nda-niimi Collective (Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring, 2014), 351.

15. George Katsiaficas, The Imagination of the New Left: A Global Analysis of 1968 (Cambridge: Beacon Press, 1987), 10.

16. Ibid., 42.

17. George Katsiaficas, “The Eros Effect,” personal website, 1989, http://www.eroseffect.com/articles/eroseffectpaper.PDF, 1.

18. Herbert Marcuse, Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud (Boson: Beacon Press, 1992).

19. Katsiaficas, “Remembering May ’68,” n.p.

20. George Katsiaficas, “The Eros Effect and the Arab Uprisings,” Z Communications, April 21, 2011, https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/the-eros-effect-and-the-arab-uprisings-by-george-katsiaficas, n.p.

21. Sidney Tarrow, Power in Movement (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 199.

22. For examples, see Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (New York: Viking Press, 1895); and Neil J. Smelser, Theory of Collective Behavior (Glencoe: Free Press, 1962).

23. Sidney Tarrow, “Dynamics of Diffusion,” in The Diffusion of Social Movements, 204–219 (209).

24. Sidney Tarrow and Doug McAdam, “Scale Shift in Transnational Contention,” in Transnational Protest and Global Activism, ed. Donatella della Porta and Sidney G. Tarrow (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 121–147.

25. Ibid., 122.

26. Doug McAdam, Sidney Tarrow, and Charles Tilly, Dynamics of Contention (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 333; Sidney Tarrow, The New Transnational Activism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 105.

27. Doug McAdam and Dieter Rucht, “The Cross-National Diffusion of Movement Ideas,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 528 (July, 1993): 56–74.

28. Ibid., 71.

29. Katsiaficas, “The Eros Effect and the Arab Uprisings,” n.p.

30. Beyond the study of protest activity, social movement theorists also investigate decision-making, identity construction, organizational forms, resources, culture, strategy, biography, networks, alliances, and outcomes.

31. Sidney Tarrow, Power in Movement (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

32. Ibid, 27.

33. I use the term “aboriginal” in reference to this statistic, as this is the term used by Statistics Canada, who define it in particular ways.

34. Katsiaficas, “The Eros Effect,” 3.

35. Ibid., 3.

36. George Katsiaficas, “Remembering May ’68.”

37. Melissa Martin, “Round Dance: Why It’s the Symbol of Idle No More,” CBC Manitoba, January 28, 2013, http://www.cbc.ca/manitoba/scene/homepage-promo/2013/01/28/round-dance-revolution-drums-up-support-for-idle-no-more, n.p.

38. Doug McAdam, “Tactical Innovation and the Pace of Insurgency,” American Sociological Review 48 (1983): 735–754; Charles Tilly, Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758–1834 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995).

39. della Porta and Tarrow, “Interactive Diffusion.”

40. Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (New York: Random House, 1977).

41. Kenneth T. Andrews and Michael Biggs, “The Dynamics of Protest Diffusion: Movement Organizations, Social Networks, and News Media in the 1960 Sit-Ins,” American Sociological Review 71, no. 5 (2006): 752–777.

42. Pamela Oliver and Dan Myers, “Diffusion Models of Cycles of Protest as a Theory of Social Movements” (conference paper, presented at the Congress of the International Sociological Association, Montreal, July 30, 1998), 2, http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~oliver/PROTESTS/ArticleCopies/diffusion_models.pdf.

43. Wood, Direct Action.

44. For studies of tactical diffusion within the dynamics of contention tradition, see, among others, Kolins Givan, Roberts, and Soule, The Diffusion of Social Movements; and McAdam, “Tactical Innovation and the Pace of Insurgency.”

45. Katsiaficas, “Remembering May ’68,” n.p.

46. Katsiaficas, “The Eros Effect,” 8.

47. Tanya Kappo, interviewed by Hayden King, “ ‘Our People Were Glowing’: An Interview with Tanya Kappo,” in The Winter We Danced, 70.

48. Katsiaficas, “The Eros Effect and the Arab Uprisings,” n.p.

49. Katsiaficas, “Remembering May ’68,” n.p.

50. Tarrow, The New Transnational Activism, 103–109.

51. Sean Chabot, Transnational Roots of the Civil Rights Movement: African American Explorations of the Gandhian Repertoire (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2012); and Wood, Direct Action.

52. Francesca Polletta, “ ‘It Was Like a Fever …’: Narrative and Identity in Social Protest,” Social Problems 45, no. 2 (1998): 137–159.

53. Ibid., 138.