They hold the throne in their hand. The whole realm is in their hand. The country, the apportioning of men’s livelihoods is in their hand … The springs of hope and of fear are in their hand … In their hand is the power to decide who shall be humbled and who exalted … Our people is in their hand, education is in their hand … If the West continues to be what it is, and the East what it is, we shall see the day when the whole world is in their hand.

Akbar Illahabadi, in the 1870s

Early on the morning of 5 May 1798, Napoleon slipped out of Paris to join a 40,000-strong French army sailing towards Egypt. A popular general after his victories in northern Italy, he had been lobbying his civilian superiors for an invasion of Britain. But the Royal Navy was still too strong, and the French were not ready to confront it. In the meantime, France needed colonies in order to prosper, as its foreign minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand believed, and a presence in Egypt would not only compensate the French for their loss of territory in North America, it could also pose a serious challenge to the British East India Company, which produced highly profitable cash crops in its Indian possessions.

Expanding across India, the British had expelled the French from most of their early bases on the coast. In 1798, the British were locked into a fierce battle with one of their most wily Indian opponents, Tipu Sultan, an ally of France. French control of Egypt could tip the balance of power against the British in India while also deterring the Russians, who eyed the Ottoman Empire. ‘As soon as I have made England tremble for the safety of India,’ Napoleon declared, ‘I shall return to Paris and give the enemy its death blow.’ Apart from his country’s geopolitical aims, Napoleon cherished his own private fantasy of conquering the Orient. ‘Great reputations’, he was convinced, ‘are only made in the Orient; Europe is too small.’1 From Egypt he planned to push eastwards in an Alexander-the-Great-style invasion of Asia, with him riding an elephant and holding a new, personally revised Koran that would be the harbinger of a new religion.

Napoleon travelled to Egypt with a large contingent of scientists, philosophers, artists, musicians, astronomers, architects, surveyors, zoologists, printers and engineers, all meant to record the dawn of the French Enlightenment in the backward East. The momentousness of the occasion – the first major contact between modernizing Europe and Asia – was not lost on Napoleon. On board his ship in the Mediterranean, he exhorted his soldiers: ‘You are about to undertake a conquest, the effects of which on civilization and commerce of the world are

immeasurable.’2 He also drafted grand proclamations addressed to the Egyptian people, describing the new French Republic based upon liberty and equality, even as he professed the highest admiration for the Prophet Muhammad and Islam in general. Indeed the French, he claimed, were also Muslims, by virtue of their rejection of the Christian Trinity. He also made some noises – familiar to us after two centuries of imperial wars disguised as humanitarian interventions – about delivering the Egyptians from their despotic masters.

Appearing without warning in Alexandria in July 1798, the French overcame all military opposition as they proceeded towards Cairo. Egypt was then nominally part of the Ottoman Empire though it was ruled directly by a caste of former slave-soldiers called Mamluks. Its meagre armies were not equipped to fight war-hardened French soldiers who outnumbered the Egyptians and were also backed by the latest military technology.

Reaching Cairo after some easy victories, Napoleon commandeered a mansion for himself on the banks of the then Azbakiya Lake, installed the scholars from his baggage train at a new Institut d’Égypte, and set about politically engineering Egypt along republican lines. He thought up a Divan consisting of wise men, an Egyptian version of the Directory that exercised executive power in Paris. But where were wise men to be found in Cairo, which had been abandoned by its ruling class, the Ottoman Mamluks? Much to their bewilderment, Cairo’s leading theologians and religious jurists found themselves promoted to political positions and frequently summoned for consultation by Napoleon – marking the first of many such expedient attempts at politically empowering Islam by supposedly secular Westerners in Asia.

Suppressing his allegiance to the Enlightenment, Napoleon vigorously appeased conservative Muslim clerics in the hope they might form the bulwark of pro-French forces in the country. He dressed up in Egyptian robes on the Prophet’s birthday and, much to the disquiet of his own secular-minded soldiers, hinted at a mass French conversion to Islam. Some sycophantic (and probably, derisive) Egyptians hailed him as Ali Bonaparte, naming him after the revered son-in-law of the Prophet. This encouraged Napoleon to suggest to the clerics

that the Friday sermon at al-Azhar Mosque, one of Islam’s holiest buildings, be said in his name.

The devout Muslims were flabbergasted. The head of the Divan, Sheikh al-Sharqawi, recovered sufficiently to say, ‘You want to have the protection of the Prophet … You want the Arab Muslims to march beneath your banners. You want to restore the glory of Arabia … Become a Muslim!’3 An evasive Napoleon replied: ‘There are two difficulties preventing my army and me from becoming Muslims. The first is circumcision and the second is wine. My soldiers have the habit from their infancy, and I will never be able to persuade them to renounce it.’4

Napoleon’s attempt to introduce Egyptian Muslims to the glories of French secularism and republicanism were equally doomed. Cairenes deplored his dramatic alterations to the cityscape, and the corrupting influence of the French in general. As one observer wrote, ‘Cairo has become a second Paris, women go about shamelessly with the French; intoxicating drinks are publicly sold and things are committed of which the Lord of Heaven would not approve.’5 In the summer of 1798, Napoleon made it mandatory for all Egyptians to wear the tricolour cockade, the knotted ribbon preferred by French republicans. Inviting members of the Divan to his mansion, he tried to drape a tricolour shawl over the shoulders of Sheikh al-Sharqawi. The Sheikh’s face turned red from fear of blasphemy and he flung it to the ground. An angry Napoleon insisted that the clerics would have to wear the cockade at least, if not the shawl. An unspoken compromise was finally arrived at: Napoleon would pin the cockade to the chests of the clerics, and they would take it off as soon as they left his company.

The Islamic eminences may have been trying to humour their strange European conqueror while trying to live for another day. Many other Muslims saw plainly the subjugation of Egypt by a Christian from the West as a catastrophe; and they were vindicated when French soldiers, while suppressing the first of the Egyptian revolts against their occupation, stormed the al-Azhar mosque, tethered their horses to the prayer niches, trampled the Korans under their boots, drank wine until they were helpless and then urinated on the floor.

Napoleon, though ready to burn hostile villages, execute prisoners and tear down mosques for the sake of wide roads, actually indulged in fewer atrocities in Egypt than he was to elsewhere; he was always keen to express his admiration for Islam. Still, the Egyptian cleric and scholar ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti, who chronicled Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt, described it as ‘great battles, terrible events, disastrous facts, calamities, unhappiness, sufferings, persecutions, upsets in the order of things, terror, revolutions, disorders, devastations – in a word, the beginning of a series of great misfortunes’.6 And this was the reaction of a somewhat sympathetic witness. When the news of Napoleon’s exploits arrived in the Hejaz, the people of Mecca tore down the drapery – traditionally made in Egypt – around the sacred Kaaba.

The dramatic gesture clearly expressed how many Muslims would see Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt. It had disrupted nothing less than the long-established cosmic order of Islam – something that human history had shown to be more than a widely shared delusion.

The word ‘Islam’, describing the range of Muslim beliefs and practices across the world, was not used before the nineteenth century. But few Muslims anywhere over the centuries would have doubted that they belonged to both a collective and an individual way of life, an intense solidarity based on certain shared values, beliefs and traditions. To be a good Muslim was to belong to a community of like-minded upholders of the moral and social order. It was also to participate in the making and expansion of the righteous society of believers and, by extension, in the history of Islam as it had unfolded since God first commanded the Prophet Muhammad to live according to His plan. This history began with astonishing successes, and for centuries it seemed that God’s design for the world was being empirically fulfilled.

In AD 622, the first year of the Islamic calendar, Muhammad and his band of followers established the first community of believers in a small town in Arabia. Less than a century later, Arab Muslims were in Spain. Great empires – Persian and Byzantine – fell before the energetically expanding community of Muslims. Islam quickly became the new symbol of authority from the Pyrenees to the Himalayas, and the

order it created wasn’t just political or military. The conquerors of Jerusalem, North Africa and India brought into being a fresh civilization with its own linguistic, legal and administrative standards, its own arts and architecture and orders of beauty.

The invading Mongols broke into this self-contained world in the thirteenth century, briskly terminating the classical age of Islam. But within fifty years the Mongols had themselves converted to Islam and become its most vigorous champions. Sufi orders spread across the Islamic world, sparking a renaissance of Islam in non-Arab lands. From Kufa to Kalimantan, the travelling scholar, the trader and the Friday assembly gave Islam an easy new portability.

Indeed, Islam was as much a universalizing ideology as Western modernity is now, and it successfully shaped distinctive political systems, economies and cultural attitudes across a wide geographical region: the fourteenth-century Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta had as little trouble getting jobs at imperial courts in India or in West Africa as a Harvard MBA would in Hong Kong and Cape Town today. The notion of a universal community of Muslims, the umma, living under the symbolic authority of a khalifa (caliph), in a Dar al-Islam (land of Muslims), which was distinct from the remote and peripheral Dar al-Harb (land of war), helped Muslims from Morocco to Java to imagine a central place in the world for themselves and their shared values.

Itinerant Muslim traders from India were still displacing Hinduism and Buddhism in Indonesia and even Indochina as late as the seventeenth century. Extensive mercantile networks and pilgrimage routes to Mecca from all corners of the world affirmed the unity of Dar al-Islam. World trade in fact depended on Muslim merchants, seafarers and bankers. For a Muslim in North Africa, India or South-east Asia, history retained its moral and spiritual as well as temporal coherence; it could be seen as a gradual working out of God’s plan.

Though beset by internal problems in the eighteenth century, Muslim empires still regarded Europeans as only slightly less barbarous than their defeated Crusader ancestors. So the success of Napoleon suggested something inconceivable: that the Westerners, though still quite crude, were beginning to forge ahead.

Europe was to express, as the nineteenth century progressed, an idea of itself through its manifold achievements of technology, constitutional government, secular state and modern administration; and this idea, which emerged from the American and French revolutions and which seemed to place the West in the avant-garde of progress, would be increasingly hard to refute. Already in 1798, a remarkably high degree of organization defined the post-revolutionary French state as well as the French people, who were coming together on the basis of an apparently common language, territory and history to constitute a separate and distinct ‘nation-state’.

Faced with the evidence of Europe’s advantages, many Muslims were initially bemused and unable to assess it correctly. ‘The newly established republic in France’, the Ottoman historian Asim recognized in 1801, ‘is different from the other Frankish polities.’ But then he went on to say: ‘Its ultimate basis is an evil doctrine consisting of the abandonment of religion and the equality of rich and poor.’ As for parliamentary deliberations, they were ‘like the rumblings and crepitations of a queasy stomach’.7 Some of this cultural arrogance lingered in the eyewitness accounts of Napoleon’s conquest by ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti. The cleric generally found French practices distasteful, even barbaric: ‘It is their custom’, he wrote, ‘not to bury their dead but to toss them on garbage heaps like the corpses of dogs and beasts, or to throw them into the sea.’8 ‘Their women do not veil themselves and have no modesty … They [the French] have intercourse with any woman who pleases them and vice versa.’9 Al-Jabarti also mocked French hats, the European habit of peeing in public, and the use of toilet paper. He contemptuously dismissed Napoleon’s claim to be a protector of Islam, laughing at the bad Arabic grammar of the Frenchman’s proclamations, and he sniggered when the French failed to launch a hot-air balloon at one of their demonstrations of European scientific prowess.

Al-Jabarti’s limited experience of political institutions made him misunderstand French revolutionary ideals: ‘their term “liberty” means,’ he concluded too hastily, ‘that they are not slaves like the Mamluks’.10 He sensed the hostility to his own Islamic values in Napoleon’s claim that ‘all the people are equal in the eyes of God’.

‘This is a lie, and ignorance, and stupidity,’ he thundered. ‘How can this be when God has made some superior to others?’11

Still, al-Jabarti, who had been educated at al-Azhar, couldn’t fail to be impressed when he visited the Institut d’Égypte, where the intellectuals in Napoleon’s entourage had a well-stocked library.

Whoever wishes to look up something in a book asks for whatever volumes he wants and the librarian brings them to him … All the while they are quiet and no one disturbs his neighbor … among the things I saw there was a large book containing the Biography of the Prophet … The glorious Qur‘an is translated into their language! … I saw some of them who know chapters of the Qur’an by heart. They have a great interest in the sciences, mainly in mathematics and the knowledge of languages, and make great efforts to learn the Arabic language and the colloquial. 12

Al-Jabarti was also struck by the efficiency and discipline of the French army, and he followed with great curiosity the electoral processes in the Divan that Napoleon had created, explaining to his Arab readers how members wrote their votes on strips of paper, and how majority opinion prevailed.

Al-Jabarti was not entirely deaf to the lessons from Napoleon’s conquest: that the government in the world’s first modern nation-state did not merely collect taxes and tributes and maintain law and order; it could also raise a conscript army, equip well-trained personnel with modern weapons, and have democratic procedures in place to elect civilian leaders. Two centuries later, al-Jabarti seems to stand at the beginning of a long line of bewildered Asians: men accustomed to a divinely ordained dispensation, the mysterious workings of fate and the cyclical rise and fall of political fortunes, to whom the remarkable strength of small European nation-states would reveal that organized human energy and action, coupled with technology, amount to a power that could radically manipulate social and political environments. Resentfully dismissive at first of Europe, these men would eventually chafe at their own slothful and uncreative dynastic rulers and weak governments; and they would arrive at a similar conviction: that their societies needed to attain sufficient strength to meet the challenge of the West.

Napoleon’s occupation of a large country like Egypt was always tenuous. Despite his praise of Islam, the population remained hostile. Revolts erupted in the major towns, provoking the French into ugly reprisals, including the vandalism and drunken orgies at the al-Azhar mosque. The British navy finally made Napoleon’s position untenable by blockading Egypt, isolating him from France and his supply lines. By August 1799 when Napoleon left Egypt as surreptitiously as he had departed Paris, to begin his ascent to political supremacy in France, his Indian ally Tipu Sultan had also been overcome by the British. There were no more conquests for him to accomplish in Asia. He would now concentrate on Europe, striving, in the fearful words of the Turkish ambassador to Paris, ‘day and night like a fiercely biting dog to bring diverse mischiefs on the surrounding lands and to reduce all states to the same disorder as his own accursed nation’.13

In retrospect, Napoleon had shot out of the starting blocks too early. By 1798, the Dutch, the Spanish, the Portuguese and the British had all secured crucial footholds in Asian territories. But the European conquest of Asia wouldn’t get fully under way until after Napoleon himself was comprehensively defeated in 1815. Exhausted by war, the five great European powers – Britain, France, Prussia, Russia and Austria – would agree to maintain a balance of power in Europe. Their pugnacity at home restrained by treaties, Western nations would grow more aggressive in the East, no longer content with beachheads on the vast continent of Asia. In 1824 the British, ensconced in eastern India, began their long subjugation of Burma. In the same year an Anglo-Dutch treaty confirmed British control of Singapore and the Malay states of the Peninsula while demarcating the influence of the Netherlands over Java. Neither Britain nor the Dutch, in turn, stood in the way of French domination of Vietnam.

By the time of Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the British had conquered a third of India; they would soon be paramount over the rest, inaugurating a potent presence in mainland Asia that was to help them force open China to European traders, and turn the rest of Asia into

a European dependency. The speed and audacity of the British conquests in India seem more astonishing given the low profile they had kept during their centuries-long presence in the subcontinent. Arriving at the brilliantly adorned Mughal court in Agra in 1616, Sir Thomas Roe, the first accredited English ambassador to India, had struggled to keep his national flag aloft. Roe’s ruler in England, James I, who wanted a formal trade treaty with the Mughal emperor Jahangir, had told him to be ‘careful of the preservation of our honour and dignity’14 and Roe managed to avoid the bowing and scraping expected of ambassadors at the Mughal court. But he felt acutely the shabbiness of the gifts he had brought from England for the aesthete Jahangir, and he could not entirely overcome the Mughal emperor’s scepticism about a supposedly great English king who concerned himself with such petty things as trade.

As late as 1708, the British East India Company’s president felt it imperative to cringe while addressing the Mughal emperor, declaring himself as ‘the smallest particle of sand … with his forehead at command rubbed on the ground’.15 In 1750 when the Mughal Empire, weakened by endless wars and invasions, was imploding into a number of independent states, the only place where the British enjoyed territorial sovereignty was the then obscure fishing village of Bombay (Mumbai). Their luck finally turned in the next few years. In 1757, after a battle with Bengal’s Muslim viceroy, the East India Company found itself in possession of a territory three times larger than England. Less than a decade later, the Company had successfully deployed the same combination of political skulduggery and military force to undermine the ruler of Awadh, the largest of the Mughal Empire’s provinces.

The British subsequently controlled and ruthlessly exploited economically a large part of eastern India. ‘The world has never seen’, Bengal’s pioneering novelist Bankim Chandra Chatterji (1838 – 94) would write, ‘men as tyrannical and powerful as the people who first founded the Britannic empire in India … The English who came to India in those days were affected by an epidemic – stealing other people’s wealth. The word morality had disappeared from their vocabulary.’16 Chatterji worked for the British administration in Bengal and had to necessarily tone down his criticism. There was no

such inhibition on the righteous rage of Edmund Burke, then a member of the British Parliament. ‘Young men (boys almost) govern there’, he wrote about Bengal in 1788,

without society and without sympathy with the natives … Animated with all the avarice of age and all the impetuosity of youth, they roll in one after another, wave after wave; and there is nothing before the eyes of the natives but an endless, hopeless prospect of new flights of birds of prey and passage.17

The Muslim historian Ghulam Hussain Khan Tabatabai (1727 – 1806), who also worked for the British in Bengal, concurred about the corruption and insularity of his bosses. ‘No love, and no coalition can take root’, he wrote in a history of India published in 1781, ‘between the conquerors and the conquered.’18 This hardly mattered to the British. As Haji Mustapha, a Creole convert to Islam who translated Tabatabai’s book into English in 1786, pointed out in his introduction: ‘The general turn of the English individuals in India seems to be a thorough contempt for the Indians (as a national body). It is taken to be no better than a dead stock that may be worked upon without much consideration, and at pleasure.’19 Increasingly powerful in India, the British could afford to be more aggressive in China, where European traders, confined to the port of Canton, had long fantasized about the potentially huge inland market for their goods. Since they occupied rich agricultural lands in eastern India, the British were particularly keen to find buyers for their produce, especially opium, and they chafed at the arbitrary and opaque nature of China’s imperial authority. Emboldened by their successes in India, the British travelled a much shorter distance between awe and contempt in confronting the rulers of China.

Though less extensive than the land of Islam, a unitary Chinese empire persisting over two millennia had made for a high degree of self-absorption. Tribute-bearing foreigners from places as far away as Burma allowed the Chinese to think of themselves as inhabitants of the ‘Middle Kingdom’. Indeed, not even Islam could parallel the extraordinary longevity and vitality of Chinese Confucianism, which regulated everything from familial relations to political

and ethical problems and had eager imitators in Korea, Japan and Vietnam.

In 1793, the British envoy Lord Macartney led a diplomatic mission to Beijing (Peking) with a letter from King George III asking Emperor Qianlong for a commerce treaty, more ports for British traders and ambassadorial presence at his court. Like Sir Thomas Roe before him, Macartney faced many threats to his dignity. His retinue was made to travel under a banner that said, in Chinese, ‘Ambassador bearing tribute from the country of England’. Macartney also had to engage in a long and delicate diplomatic dance to avoid prostrating himself full-length in the ceremonial kowtow before the emperor. He bent one knee instead in the emperor’s presence, and handed over various presents attesting to Britain’s advanced technical and manufacturing skills, such as brass howitzers and astronomical instruments. The Chinese emperor, then a fit eighty-year-old, graciously asked after King George’s health and offered Macartney some rice wine during a ‘sumptuous’ banquet, which struck the Englishman as possessing a ‘calm dignity, that sober pomp of Asiatic greatness, which European refinements have not yet attained’.20

The British delegation was treated with bland courtesy for a few more days before being abruptly ushered out of the country with a reply from the Celestial Emperor that stated unequivocally that he had ‘never valued ingenious articles’ and had not ‘the slightest need of England’s manufactures’. It was right that ‘men of the Western Ocean’ should admire and want to study the culture of his empire. But he could not countenance an English ambassador who spoke and dressed so differently fitting into the ‘Empire’s ceremonial system’. And, the emperor added, it would be good if the English king could ‘simply act in conformity with our wishes by strengthening your loyalty and swearing perpetual obedience’.21

The letter had been drafted well before Lord Macartney arrived in Beijing. The condescending tone reflected the Chinese elite’s exalted sense of their country’s pre-eminence, and their determination to protect the old political system in which rich families and landowners supplied well-schooled officials for the administration, and trade was conducted over land and sea with neighbours. The Chinese also knew of the growing power of the ‘barbarians’ in Asia, where the Europeans

had taken a lead in maritime trade, setting up military posts and trading stations across India’s coast and South-east Asia. ‘It is said’, Qianlong wrote to his Grand Minister, ‘that the English have robbed and exploited the merchant ships of the other western ocean states so that the foreigners along the western ocean are terrified of their brutality.’22 The emperor thought it best to keep such aggressive adventurers at bay.

The British persisted, sending another, less expensive embassy to the Qing court in 1816. This time, the Chinese absolutely insisted on the kowtow, and did not let the ambassador enter Beijing when he refused to ritually abase himself before the Chinese emperor.

But China’s bluff was about to be called. Lord Macartney, who had been governor of Madras (Chennai) in British India, had shrewdly noted during his travels in China that though the country, ‘an old, crazy, first rate man-of-war’, could ‘overawe’ her ‘neighbours merely by her bulk and appearance’, it was prone to drift and be ‘dashed to pieces on the shore’.23 The nautical metaphors were apt. Explaining why China had dropped out of world history, Hegel had pointed to its indifference to maritime exploration. It would be from the sea that European powers would soon probe China’s weaknesses and scratch its wounds. And, like the Mughals and the Ottomans, the Manchus would know the bitter consequences of ignoring the West’s innovations of state-backed industry and commerce.

As the Chinese would come to do again in more recent times, they exported much more to Europe and America – mostly tea, silks and porcelains – than they imported, creating a severe balance-of-payments problem for the West which found its precious silver disappearing into Chinese hands. The British East India Company hit upon an alternative mode of payment once it increased its stranglehold over the fertile agricultural lands of eastern India. It was opium, which grew luxuriantly and could be cheaply processed into smokable paste, speedily shipped to southern China and sold through middlemen at Canton to the Chinese masses.

The export of opium exponentially increased revenues and quickly reduced Britain’s trade deficit with China; mass Chinese intoxication became central to British foreign policy. But the easy availability of the

drug quickly created a problem of addiction in the country. In 1800, the Chinese forbade the import and production of opium; in 1813, they banned smoking altogether.

Still, the British kept at it: by 1820, there was enough opium coming into China to keep a million people addicted, and the flow of silver had been reversed.24 In the 1830s Emperor Daoguang, faced with a growing scarcity of silver, considered legalizing opium. But he had to contend with a vociferous anti-opium lobby. According to one of the petitioners to the emperor, opium was a dangerous conspiracy organized by red-haired Westerners, which had already ‘seduced the nimble, warlike people of Java into the use of it, whereupon they were subdued, brought into subjection and their land taken possession of’. Another anti-opium campaigner claimed that ‘in introducing opium into this country, the English purpose has been to weaken and enfeeble the central empire. If not early aroused to a sense of our danger, we shall find ourselves, before long, on the last step towards ruin.’25

The anti-opium lobby suggested that smokers be deterred with the death penalty, but the sheer number of smokers raised the spectre of mass executions. In 1838, Daoguang decided to stop the trafficking and consumption of opium altogether. China’s war on drugs was conducted peacefully at first; Qing officials drew upon Confucian values of sobriety and obedience to persuade many addicts to renounce smoking, and Chinese middlemen to desist from the trade. The same moral appeal was also addressed to the Westerners, including a letter to Queen Victoria by Lin Zexu, the imperial commissioner at Canton.

Lin, an exemplary official in the Confucian tradition, had acquired a reputation for probity and competence in previous posts as governor of provinces in central China. Addressing the British potentate, he expressed amazement that traders would come to China from as far off as Britain ‘for the purpose of making a great profit’.26 He assumed naively that the British government was not aware of the immoral smugglers in Canton and would uphold the moral principles of Confucius just as vigorously as the Chinese emperor had. ‘May you, O King,’ he wrote, ‘check your wicked and sift out your vicious people before they come to China.’27 He urged the British monarch to eradicate the opium plant in Madras, Bombay, Patna and Benares and replace it with millet, barley and wheat.

With the Western traders, Lin took a tough line. When they resisted, their factories in Canton were blockaded until they yielded up their opium stocks, which were promptly flushed into the sea. Those who refused to sign bonds pledging not to indulge in opium trafficking were summarily expelled: it was then that a group of British traders first settled on the rocky island called Hong Kong.

The Chinese, however, underestimated the importance the trade in opium had assumed for the British economy. Nor did they know much about the boost of self-confidence the British had received after defeating Napoleon and becoming the paramount power in India – Lin’s letter to Queen Victoria, for instance, was not even acknowledged.

In general, growing technological power and commercial success were making Westerners change their opinion of China. Far from being the apogee of enlightenment, as it had appeared to Voltaire and Leibniz, the country was now viewed as a backward place. Even to treat it like an equal, as an American diplomat put it, would be like ‘the treatment of a child as it were an old man’.28 Furthermore, in Britain’s expanding economy of the early nineteenth century, ‘free trade’ seemed as much a universal good, to be enforced through military means, as ‘democracy’ was to appear in modern times.

A bevy of aggressive private merchants in Canton agitated for more markets in China after the relatively conservative East India Company lost its monopoly over trade in Asia in 1834. These businessmen and their lobbyists raised such an alarm about Chinese actions that the British government felt impelled to dispatch a punitive fleet to China. After arriving in June 1840, the ships blockaded Canton and sailed up China’s north coast, finally threatening the city of Tianjin and beyond it the seat of the emperor himself in Beijing. Aware of their weak military, the Qing sued for peace, ceding Hong Kong to the British and agreeing to pay an indemnity of £6 million and to reopen Canton to British traders.

This wasn’t enough for the British government. The fantasy of a big China market for British goods had grown unchecked in Britain. Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, an aggressive imperialist, raged that his representatives hadn’t exacted more stringent terms from the Chinese after defeating them. He dispatched another fleet in 1841, which, after capturing Shanghai and blocking traffic on

the lower Yangtze, threatened to assault the former capital city of Nanjing.

After suffering more military reverses the Chinese again capitulated and signed the humiliating Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, which opened five trade ports, including Shanghai, to foreigners and granted Hong Kong to the British in perpetuity. Writing to his business associates at the British firm Jardine, Matheson & Co. the Indian merchant Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy cautioned that the ‘Chinese had enough from us upon this matter … now keeping distance is far better than showing threat’.29 The Chinese themselves remained perplexed by the apparently unappeasable greed of the British. As one of the emperor’s representatives reasoned in a letter to the British:

We ponder with veneration upon the Great Emperor’s cherishing tenderness towards foreigners, and utmost justice in all his dealings. He thereby causes the whole world to participate in his favour, and to enjoy his protection, for the promotion of civilization – and the full enjoyment of lasting benefits. But the English foreigners have now for two years … on account of the investigation in the opium traffic, discarded their obedience and been incessantly fighting … what can possibly be their intention and the drift of their actions?30

The Emperor received a heavily edited account of the tough British negotiating style: ‘Although the demands of the foreigners are indeed rapacious’, his representative wrote, ‘yet they are little more than a desire for ports and the privilege of trade. There are no dark schemes in them.’

This proved to be optimistic. Demanding compensation for the opium destroyed, the British asked for more indemnities, including ransom for those cities, such as Hangzhou, that they had not occupied. Other Western nations followed suit, notably the United States, which had maintained a presence in Canton since its own liberation from British rule. The Americans insisted that the Chinese allow Protestant missionaries to work in the treaty ports. The French asked for even broader rights for Catholics, completing the identification in Chinese eyes between the West and the proselytizing religion of Christianity.

The treaties gave Western powers the right to dictate vital aspects

of China’s commercial, social and foreign policies for the next century. As it turned out, even such craven surrender of Chinese sovereignty did not satisfy the free traders. The supposedly unlimited China market failed to materialize and the trade in opium, not mentioned in the treaties but implicitly accepted by all sides, remained the main Western commercial activity. By 1900, 10 per cent of the Chinese population smoked the drug; one third of those were addicts.31

The greater their frustrations around the Chinese market, the louder British businessmen clamoured for the relaxation of remaining restrictions on trade. In 1854, as the Qing faced the growing Taiping rebellion, British, French and American representatives demanded revisions to the Nanjing Treaty facilitating free access to all parts of China, unimpeded navigation of the Yangtze, their diplomatic presence in Beijing, the legalization of opium, and the regulation of Chinese labour emigration (during the lawlessness that prevailed at the end of the Opium War, Chinese men were kidnapped or deceived into travelling to places as far away as California and Cuba to supply local demands for cheap labour).

The Chinese naturally resisted these demands. However, using an allegedly illegal Qing search of a Hong Kong-registered ship called the Arrow as a pretext the British went to war again, joined this time by the French who, under Napoleon III, were keen to flex their muscles. In 1859, Lord Elgin, the son of the earl who had taken the marble friezes from the Parthenon to England, arrived at the head of a fleet that quickly captured Canton and moved north to Tianjin.

The hapless Chinese again offered to negotiate through the viceroy of Tianjin. But Elgin was determined to deal with the imperial court itself rather than its provincial governors. The emperor in Beijing yielded and sent his representatives to sign an agreement granting full access to the Yangtze, unimpeded travel inside China for those with passports, six more treaty ports, freedom for missionaries, a diplomatic presence in Beijing, and immunity from Chinese jurisdiction for foreigners. Elgin, with the French in tow, pressed for more. And he found the excuse to move on Beijing when, amid the chaos of war, his negotiators were arrested and executed by the Chinese.

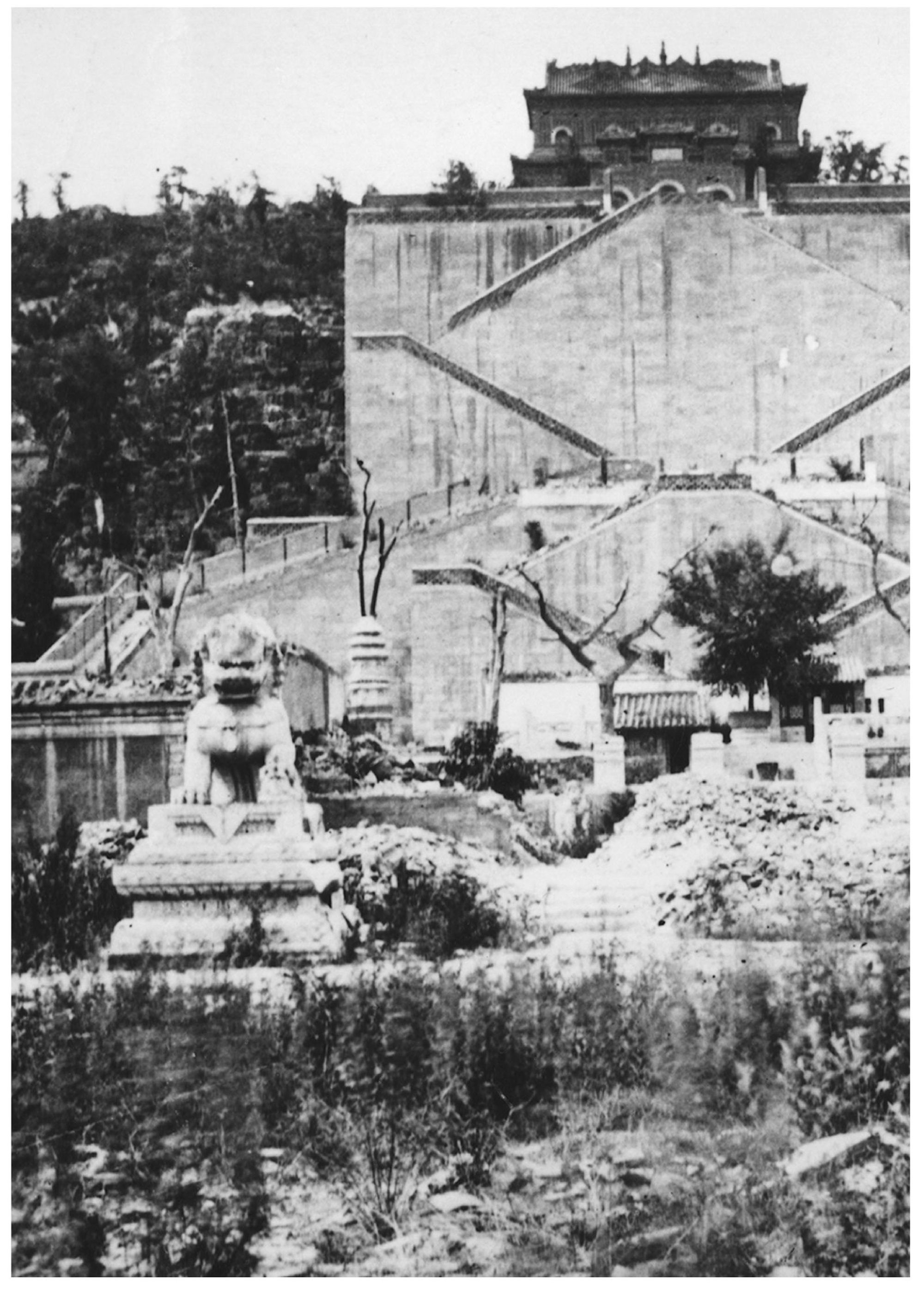

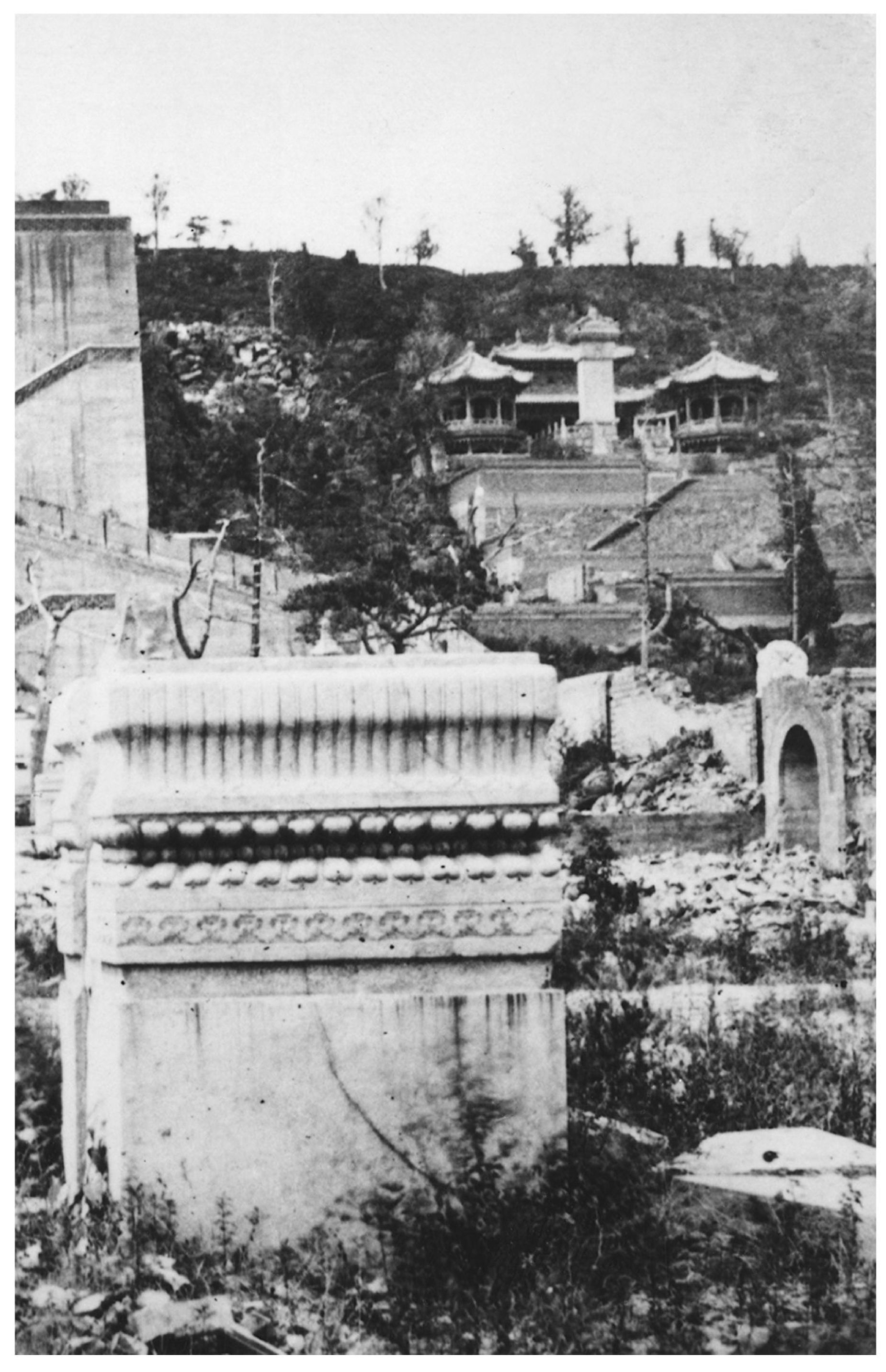

Arriving first at the city’s north-eastern outskirts as negotiations with the Chinese were under way, the French came upon the Yuan

Ming Yuan, the elegant Summer Palace, which Jesuit missionaries had designed for Emperor Qianlong, and promptly plundered it. For three days, French soldiers rampaged across the thirty-seven acres of pavilions, gardens and temples, barely believing their luck: ‘to depict’, one intoxicated looter wrote, ‘all the splendours before our astonished eyes, I should need to dissolve specimens of all known precious stones in liquid gold for ink, and to dip it into a diamond pen tipped with the fantasies of an oriental poet.’32

When Elgin arrived, the French offered to split the loot, and the earl got the Chinese emperor’s green jade baton. Elgin, who had helped quell the Indian Mutiny before coming to China, was a reluctant imperialist by the standards of his time. He considered the broad thrust of British policy in China to be ‘stupid’. ‘I hate the whole thing so much that I cannot trust myself to write about it’, he wrote in his diary as British warships under his command bombed and killed 200 civilians in Canton.33 But when he received news of European prisoners dying in Chinese custody, Elgin’s remaining scruples vanished.

The Chinese had to be taught a severe lesson. The French excused themselves from this act of retribution, in which British troops torched the Summer Palace, before Elgin proceeded to sign the treaty that gave the British more indemnities, and another treaty port (in Tianjin) and legations for all Western powers in Beijing. The Summer Palace burnt for two days, covering Beijing with thick black smoke. The ‘crackling and rushing noise’, one English observer wrote, ‘was appalling … the sun shining through the masses of smoke gave a sickly hue to every plant and tree, and the red flame gleaming on the faces of the troops engaged made them appear like demons glorying in the destruction of what they could not replace.’34

The Chinese were relatively slow to awaken to their perilous position in the world. The innovative steamships of the British had navigated far up the Yangtze, threatening inland Chinese cities, and the British quickly mobilized Indian soldiers against the Chinese. But this evidence of a globally resourced maritime power only prompted the Confucian scholar-official Wei Yuan, obviously deeply immersed in the Middle Kingdom, to remark in the light of these events that ‘India is nearby and must not be considered [a] barren land on the periphery

[of the world]’.35As late as 1897, two years after Japan had brutally exposed the military weakness of Qing China, Liang Qichao was arguing that ‘China cannot be compared to India or Turkey’.36 It took the cumulative effect of internal and external political shocks – the Taiping Rebellion, defeat by Japan in Korea, and the subsequent scramble for Chinese territory by European powers – to instil a new sense of the changing global topography among the Chinese elite.

By late 1898, when the failure of the so-called ‘Hundred-Day’ reforms at the Qing court seemed clear, China had finally begun to look, in Liang’s view, as vulnerable to the West as Turkey and India, its predicament part of a global one caused by Western-style capitalism and imperialism. Soon Liang, forced into exile in Japan, was closely examining the situation in the Philippines, where the United States was fighting a popular insurgency, for parallels with China. The philosopher Yan Fu described an increasingly widespread Chinese view of the Opium War by the late 1890s:

When the Westerners first came, bringing with them immoral things that did harm to people [i.e., opium], and took up arms against us, this was not only a source of pain to those of us who were informed; it was then and remains today a source of shame to the residents of their capital cities. At the time, China, which had enjoyed the protection of a series of sagacious rulers, and with its vast expanse of territories, was enjoying a regime of unprecedented political and cultural prosperity. And when we looked about the world, we thought there none nobler among the human race than we.37

Since the 1890s, the Opium War and the destruction of the Summer Palace have been carefully remembered in China as the most egregious of the humiliations the country suffered at the hands of the West in the nineteenth century. In an essay titled ‘The Death Traffic’ written in 1881, a youthful Rabindranath Tagore marvelled at how a ‘whole nation, China, has been forced by Great Britain to accept the opium poison – simply for commercial greed’. Tagore was aware that his own grandfather Dwarkanath Tagore was one of the Indian businessmen who had become rich by shipping opium to China. ‘In her helplessness’, Tagore wrote, ‘China pathetically declared: “I do not

require any opium.” But the British shopkeeper answered: “That’s all nonsense. You must take it.”’38

Explaining Europe’s growing dominance over the world, the conservative Bengali writer Bhudev Mukhopadhyay mourned that ‘this Chinese War remains a good example of the fact that virtue does not always triumph. In fact, victory often lies with the unrighteous.’39 For many Indians this was also true of the Mutiny of 1857, which spelt the end of centuries-long Muslim rule over India.

Muslims had been the biggest losers as the British East India Company became the major military power in the subcontinent. It was the defeat of two Muslim rulers in central and south India that cleared the Company’s path to unchallenged supremacy over India, and then the British moved quickly, annexing the hinterland piecemeal in open battle or through treaty, finally subduing the great Muslim-majority lands of the Punjab in 1848.

All through the first half of the nineteenth century, Muslim ruling classes in north India were either scornfully deposed by the British or emasculated by restrictions on their authority. The most egregious of these annexations occurred in 1856 in the province of Awadh, which since the late eighteenth century had been subordinate to British commercial and political interests, and had been seen, as the British governor-general put it, as a ‘cherry which will drop into our mouths some day, it has long been ripening’.40 Successive Shiite Muslim kings had made Lucknow the capital city of Awadh. It was famous for its distinctive architecture, which blended Persian with European forms, and for its culturally rich courts which attracted some of north India’s best poets, artists, musicians and scholars. Wajid Ali Shah, Lucknow’s last king, sang, danced and wrote poetry to a high standard, but to the British these accomplishments were just another sign of his unfitness to rule. Awadh’s landowning aristocracy, which mostly supported Wajid Ali Shah, had long been apprehensive of the British intentions before the Europeans, no longer willing to wait for it to drop, finally plucked the cherry. Exiling the popular king to Calcutta, the British moved quickly to extract the steepest possible land revenues from landlords and peasants.

The realm of culture, too, was far from insulated from the larger

social and economic changes unleashed by the British. In the decades leading up to the Mutiny, Lucknow had replaced Delhi as the premier city of north India. However Delhi had remained an intellectual and cultural centre for north Indian Muslims, its madrasas drawing the most talented men from the provinces. Loss of territory and influence had diminished the Mughal emperors in Delhi into figureheads as early as the mid-eighteenth century, but the British continued to give the Mughals generous pensions and allowed them to hold shows of pomp and ceremony periodically. Despite their infirmity, the emperors retained, in British eyes, the symbolic value of belonging to India’s oldest and most prestigious ruling dynasty. Mushairas, public poetry recitals, attracted huge audiences, and the rivalry of the two greatest poets at the Mughal court, Zauq and Ghalib, fuelled the gossip in the city’s alleys. A young poet called Altaf Husain Hali trekked miles from his province to attend Delhi’s celebrated institutions of education, and to hang out with the poets and intellectuals whose ‘meetings and assemblies’, he later wrote, ‘recalled the days of Akbar and Shah Jahan’, culturally the most assured among Mughal emperors.41

However, this turned out to be, as Hali wrote, ‘the last brilliant glow of learning in Delhi’. Passing through Delhi in 1838, the English diarist Emily Eden lamented the city’s steady incorporation into a profit-minded empire. ‘Such stupendous remains of power and wealth passed and passing away – and somehow I feel that we horrid English have just “gone and done it”, merchandised it, revenued it and spoiled it all.’42 As education and judicial institutions were secularized, the ulema, the Muslim clergy, found it difficult to find a livelihood for itself. The replacement of Persian by English as the official language also undermined the traditional cultural world of Indian Muslims. As Hali recalled:

I’d been brought up in a society that believed that learning was based only on the knowledge of Arabic and Persian … nobody even thought about English education, and if people had any opinion about it all it was as a means of getting a government job, not of acquiring any kind of knowledge.43

But here, too, the Muslims’ former subjects – Hindus – seemed to be favoured by the new rulers, and were quick to educate themselves

in Western-style institutions and assume the lowly administrative positions assigned to them. The British were beginning to replace their economic and political regime of pure plunder, as had existed in Bengal, with monopoly interests in shipping, banking, insurance and trade, and administrative structures. They enlisted native collaborators, such as the middlemen who expedited the lucrative export of opium grown in India to China, but these tended to be Hindu, Sikh or Parsi rather than Muslim.

The British indifference to Indian society and culture that Edmund Burke and the Indian historian Ghulam Hussain Khan Tabatabai had noticed in the previous century was replaced by increased cultural and racial aggression. Lord Macaulay dismissed Indian learning as risibly worthless, enjoining the British in India to create ‘a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinion, in morals, and in intellect’. Convinced of their superiority, the British sought to entrench it with profound social and cultural reforms wherever they could in India. Often run by Christian missionaries, British-style schools, colleges and universities in India were soon churning out faux-Englishmen of the kind Macaulay had hoped for.

Many Muslims spurned this modern education out of fear of deracination. They mostly watched helplessly as the British set up plantations, dug canals and laid roads, and turned India into a supplier of raw materials to, and exclusive market for, British industries. Artisan communities in north Indian towns, which tended to be Muslim, were pauperized as British manufactured goods flooded Indian bazaars. Gandhi, one of the most prominent defenders of the local artisan, was to later sum up the multifarious damage inflicted on India by British rule in his Declaration of Indian Independence in 1930:

Village industries, such as hand spinning, have been destroyed … and nothing has been substituted, as in other countries, for the crafts thus destroyed. Customs and currency have been so manipulated as to bring further burdens on the peasantry. British manufactured goods constitute the bulk of our imports. Customs duties betray partiality for British manufacturers, and revenue from them is not used to lessen the burden on the masses but for sustaining a highly extravagant

administration. Still more arbitrary has been the manipulation of the exchange which has resulted in millions being drained away from the country … All administrative talent is killed and the masses have to be satisfied with petty village offices and clerkships … the system of education has torn us from our moorings.

Elsewhere, these wrenching private and social makeovers were proving too traumatic for people accustomed to living by the light of custom and tradition. Unprotected by tariffs, which the British insisted on reducing, the nascent local industries of Egypt, Ottoman Turkey and Iran could not compete with the manufactured products imported from Europe. Not surprisingly, merchants, weavers and artisans in the bazaars of Cairo and Najaf, who perceived a direct threat from European businessmen and free traders, were at the forefront of anti-Western movements in the late nineteenth century.

India’s most famous thinker of that century, Swami Vivekananda (1863 – 1902), articulated a widespread moral revulsion among Asians for their European masters:

Intoxicated by the heady wine of newly acquired power, fearsome like wild animals who see no difference between good and evil, slaves to women, insane in their lust, drenched in alcohol from head to foot, without any norms of ritual conduct, unclean, materialistic, dependent on material things, grabbing other people’s land and wealth by hook or crook … the body their self, its appetites their only concern – such is the image of the western demon in Indian eyes.44

Westerners in Asia were increasingly seen as engaging in a deliberate assault on indigenous ways of life. Native frustration and grievances were inevitably articulated through religion, which, as Marx shrewdly pointed out, was much more than a belief system: it was a ‘general theory of the world, its encyclopaedic compendium, its logic in a popular form, its spiritualistic point d’honneur, its enthusiasm, its moral sanction, its solemn complement, its universal source of consolation and justification’.45 Native rage, quietly simmering, often erupted into violence: the Boxer Rising in China, the tribal disturbances in east-central India at the very end of the nineteenth century, the Mahdist revolt in Sudan, the Urabi revolt in Egypt in

1882 and the tobacco revolution in Iran in 1891 would signify the strength of unorganized anti-West xenophobia, often accompanied by a desperate desire to resurrect a fading or lost socio-cultural order.

The Indian Mutiny of 1857 was one such eruption. In the early nineteenth century, marginalized and embittered Muslims had begun to be receptive to the puritanical and scripturalist reformers of Islam – now known as Wahhabis – then growing dominant in Arabia. Claiming that India was Dar al-Harb, Muslim theologians and activists declared jihads in 1803 and again in 1826 against the British and their Indian collaborators. Overrunning parts of north-west India, the jihadists were finally suppressed in 1831 at the Battle of Balakot, which was to assume a tragic aura in South Asian Islamic lore comparable to the martyrdom of Imam Hussein at Karbala in AD 680.

The Mutiny was a bigger explosion than any of these scattered rebellions mounted by Indian Muslims against the British. It was sparked by rumours that new cartridges used by the British Indian army were greased with pork and beef. However, for many of India’s old elite, the Mutiny had been simmering for years as the British peremptorily redrew the social, political and economic map of India. A full measure of this was provided by the Delhi newspaper Delhi Urdu Akhbar, whose editor, Maulvi Baqar, a member of the city’s old elite, swiftly moved in 1857 from being an anodyne court-chronicler to a fiery anti-imperialist pamphleteer. ‘In truth’, he wrote, ‘the English have been afflicted with divine wrath … and their arrogance has brought them divine retribution.’46 Baqar recalled for his readers the many crimes of the British – the broken treaties with local rulers, the siphoning off of profits to Britain – and how now the tables were being turned on them by Hindus and Muslims: ‘They have taken countries and governments away from the owners on the charge of bad management and ostensibly to bring relief to their subjects. Today the same logic is reverted upon them to say that you could not administer the country.’47 One of Awadh’s dispossessed landlords offered the same vengeful logic to a British official, whom he had rescued from a furious mob:

Sahib, your countrymen came into this country and drove out our King. You send your officers round the districts to examine the titles to

the estates. At one blow you took from me lands which from time immemorial had been in my family. I submitted. Suddenly misfortune fell upon you. The people of the land rose against you. You came to me whom you had despoiled. I have saved you. But now – now I march at the head of my retainers in Lucknow to try and drive you from the country.48

The mutineers did not spare British women and children. One of the many fiery proclamations for the general revolt set out a division of labour among Indians whose ‘bounden duty’ it was

to come forward and put the English to death … some of them should kill them by firing guns … and with swords, arrows, daggers … some lift them up on spears … some should wrestle and break the enemy into pieces, some should strike them with cudgels, some slap them, some throw dust into their eyes, some should beat them with shoes … In short no one should spare any efforts, to destroy the enemy and reduce them to the greatest extremities.49

Though Hindus often led the mutineers, Muslims, especially those degraded by British rule, participated in large numbers, and the confused revolution coalesced briefly around the figure of the Mughal emperor in Delhi before it was brutally suppressed. Exhorted by public opinion back home and such venerated figures as Charles Dickens, the British in India exacted terrible reprisals as they dispersed the mutineers. Vengeful soldiers lashed tens of thousands of mutineers to the muzzles of cannons, and blew them to pieces; they left a trail of destruction across north India, bayoneting and burning their way through villages and towns.

Encamped outside Delhi, waiting for the city to fall, British soldiers dreamt of ‘a nice little diamond or two’ from the ‘rich old niggers’.50 They went on to indulge in an orgy of murder and looting of astonishing ferocity. ‘Can I do anything,’ Lord Elgin wondered as he read in China of the savage quelling of the Indian Mutiny, ‘to prevent England from calling down on herself God’s curse for brutalities committed on another feeble Oriental race? Or are all my exertions to result only in the extension of the area over which Englishmen are to exhibit how hollow and superficial are both their civilisation and Christianity?’51

Elgin answered his question by burning down the Chinese emperor’s Summer Palace. As it turned out, the Qing Empire limped on for another half-century. But British rage and vandalism after the Mutiny made even the symbols of the Mughal Empire untenable. The formal end of Muslim power in India finally came when an English soldier executed the sons of the rebellious, and – as it turned out – last Mughal emperor, and left their corpses to rot in the streets of Delhi.

A lack of unity and effective leaders doomed the Mutiny even though it had a broad mass base and the rebels vastly outnumbered the British. Writing of the mutineers in 1921, Abdul Halim Sharar, one of the first novelists in Urdu and chronicler of the fading magnificence of Lucknow, grieved that

There was not a single man of valour among them who knew anything of the principles of war or who could combine the disunited forces and make them into an organized striking force. The British, on the other hand, who were fighting for their lives, stood their ground. Facing the greatest danger they repelled their assailants and proved themselves skilled in the latest arts of war.52

The gap between the British and their Indian opponents was more than just military. As Sharar wrote bitterly,

It was impossible for the intelligence of these foreigners and their good planning and methodical ways not to prevail against the ignorance and self-effacement of India. At this time the world had assumed a new pattern of industrialized civilization, and this way was crying aloud to every nation. No one in India heard this proclamation and all were destroyed.53

However melodramatic, this was not an unrealistic assessment of European power. Helped by new technologies, superior information-gathering and attractive trade terms, Europeans were by the mid-nineteenth century challenging the Chinese, pushing Persia out of its sphere of influence in the Caucasus, invading North Africa, forcing

the Ottomans to open up their markets, promoting Christianity in Indochina and eyeing a long-secluded Japan. Eight decades after Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, the British would successfully occupy that country.

These rapid advances are not explained by hoary Western accounts of Asian ‘decline’, ‘stagnation’, or ‘Oriental Despotism’, which many self-pitying Asians also embraced. As early as 1918, the Indian sociologist Benoy Kumar Sarkar dismissed what he identified as a scholarly ‘Occidental’ superstition about an energetic Europe outpacing a somnolent Asia. Sarkar warned against the historical ‘dogma that naturally accrues to domineering and triumphant races’.54 Contemporary scholarship validates his view by demonstrating that Asia remained economically and culturally dynamic in the eighteenth century. Europe’s competitive edge was a product of its own clearly superior skills for ‘industrialized civilization’ or, more simply, organization – something that Asians would soon envy and seek to imitate – and the several advantages it had accumulated throughout the 1700s.

‘The spirit of the military organization,’ Tokutomi Soh marvelled about Europe in 1887, ‘does not stop with just the military.’ Its influence was ‘extended to all corners of society’.55 As more than one Asian observer noted, European forms of political and military mobilization (conscript armies, efficient taxation, codified laws), financial innovations (capital-raising joint-stock companies) and information-rich public cultures of enquiry and debate fed upon each other to create a formidable and decisive advantage as Europe penetrated Asia. Individually, Europeans might be no more brave, innovative, sensitive or loyal than Asians, but as members of corporate groups, churches or governments, and as efficient users of scientific knowledge, they mustered more power than the wealthiest empires of Asia.

marvelled about Europe in 1887, ‘does not stop with just the military.’ Its influence was ‘extended to all corners of society’.55 As more than one Asian observer noted, European forms of political and military mobilization (conscript armies, efficient taxation, codified laws), financial innovations (capital-raising joint-stock companies) and information-rich public cultures of enquiry and debate fed upon each other to create a formidable and decisive advantage as Europe penetrated Asia. Individually, Europeans might be no more brave, innovative, sensitive or loyal than Asians, but as members of corporate groups, churches or governments, and as efficient users of scientific knowledge, they mustered more power than the wealthiest empires of Asia.

As Sharar pointed out, a large part of Europe’s power consisted of its capacity to kill, which was enhanced by continuous and vicious wars among the region’s small nations in the seventeenth century, a time when Asian countries knew relative peace. ‘The only trouble with us,’ Fukuzawa Yukichi, author, educator and prolific commentator on Japan’s modernization, lamented in the 1870s, ‘is that we have had too long a period of peace and no intercourse with outside. In the meantime,

other countries, stimulated by occasional wars, have invented many new things such as steam trains, steam ships, big guns and small hand guns etc.’56 Required to fight at sea as well as on land, and to protect their slave plantations in the Caribbean, the British, for instance, developed the world’s most sophisticated naval technologies. Mirza Abu Talib, an Indian Muslim traveller to Europe in 1800, was among the first Asians to articulate the degree to which the Royal Navy was the key to British prosperity. For much of the nineteenth century, British ships and commercial companies would retain their early edge in international trade over their European rivals, as well as over Asian producers and traders.

There was also something else behind European dominance. Writing in 1855 to Arthur Gobineau (who first developed the theory of an ‘Aryan’ master race), Alexis de Tocqueville marvelled at how ‘a few million men, who a few centuries ago, lived nearly shelterless in the forests and in the marshes of Europe will, within a hundred years, have transformed the globe and dominated the other races’.57 Pondering the same phenomenon a year later, the Bengali writer Bhudev Mukhopadhyay reached some disquieting conclusions:

The effort to conquer other people’s lands is on the increase and becomes more intense with time among Europeans: there is a sharp edge to their thirst for material pleasures and it keeps getting sharper; these do not indicate any enhancements of moral standards or any prospect thereof … It would be logical to conclude their descendants would also inherit their penchant for marauding … If thus Europe does not need external control, who does?58

But there was to be no external control – at least not until the calamity of the First World War. It was as though the competitive energies unleashed by the American and French revolutions could not be contained within the West; they could only spread around the globe, propelling Europe’s small nation-states into Asia’s remotest regions – a standing reproach and unique threat to peoples who were neither modern nor had any means with which to achieve economic or diplomatic parity with Europe.

There had been other imperialisms in the past. Indeed, many victims of European conquests themselves belonged to powerful

empires – Ottoman Turkey, Qing China. But modern European imperialism would be wholly unprecedented in creating a global hierarchy of economic, physical and cultural power through either outright conquest or ‘informal’ empires of free trade and unequal treaties. As Fukuzawa Yukichi observed in the 1870s:

In commerce, the foreigners are rich and clever; the Japanese are poor and unused to the business. In courts of law, it so often happens that the Japanese people are condemned while the foreigners get around the law. In learning, we are obliged to learn from them. In finances, we must borrow capital from them. We would prefer to open our society to foreigners in gradual stages and move toward civilization at our own pace, but they insist on the principle of free trade and urge us to let them come into our island at once. In all things, in all projects, they take the lead and we are on the defensive. There hardly ever is an equal give and take.59

By 1900, a small white minority radiating out from Europe would come to control most of the world’s land surface, imposing the imperatives of a commercial economy and international trade on Asia’s mainly agrarian societies. Europeans backed by garrisons and gunboats could intervene in the affairs of any Asian country they wished to. They were free to transport millions of Asian labourers to far-off colonies (Indians to the Malay Peninsula, Chinese to Trinidad); exact the raw materials and commodities they needed for their industries from Asian economies; and flood local markets with their manufactured products. The peasant in his village and the market trader in his town were being forced to abandon a life defined by religion, family and tradition amid rumours of powerful white men with a strange god-on-a-cross who were reshaping the world – men who married moral aggressiveness with compact and coherent nation-states, the profit motive and superior weaponry, and made Asian societies seem lumberingly inept in every way, unable to match the power of Europe or unleash their own potential.

As European countries went from one easy conquest to another, leaving manifold social, economic and cultural disruptions in their wake, many Asian intellectuals would grow profoundly anxious about the fate of their societies. Many Muslims interpreted the loss of

their territories to Christian Europeans in India, Africa and Central Asia as God’s punishment for their religious laxity. The sense of great and permanent crisis was profound even in places such as Japan and Turkey, which were not occupied or ruled directly by European powers. As Japan’s great novelist Natsume Soseki (1867 – 1916) described it:

The civilization of the West has its origins within itself, while that of modern Japan has its origin outside the country. The new waves come one after another from the West … It is as if, before we can enjoy one dish on the table, or even know what it is, another new dish is set before us … We cannot help it; there is nothing else we can do.60

The great speed of change, and helplessness before it, was a common experience. The slightest Western contact with Asian lands inevitably sparked a drastic churning – usually for the worse. The Industrial Revolution and Europe’s demand for raw materials for its manufacturing industries not only thwarted industrialization in Asia; it also forced traditionally self-sufficient peasants across Asia to become rubber-tappers, tin-miners, coffee-growers and tea-pickers. In Islamic societies, the imperative to match Western power and build a European-style centralized state created new classes of bureaucrats, technocrats, bankers, urban workers and intellectuals which threatened to undermine the old Islamic world of the guilds, the bazaars, caravanserai, the ulema and Sufi peers. Even the unalloyed boon of modern medicine in the rising West turned into something darkly ambiguous in Asia when it helped increase populations in the absence of corresponding economic growth, compounding the problem of poverty.

The cultural effects of Europe’s primacy were no less dramatic. Civilization came to be represented by European forms of scientific and historical knowledge and ideas of morality, public order, crime and punishment, even styles of dress. Asians everywhere came up against Europe’s new self-understanding in which it was everything Asia was not: non-despotic, increasingly urban and commercial, innovative and dynamic. Rabindranath Tagore wrote exasperatedly of

Asia’s being ever a defendant in Europe’s court and ever taking her verdict as the last word, admitting that our only good is in rooting out

the three-fourths of our society along with their very foundation, and in replacing them with the English brick and mortar as planned out by English engineers.61

And Liang Qichao was not alone in worrying that such a dramatic change in his society’s external circumstances fatally damaged inner lives and older notions of morality: ‘I fear,’ he confessed in 1901 during his most pro-Western phase, ‘that mental training will gradually become more important, while moral training decays, that the materialist civilization of the West will invade China, the 400,000,000 people be led away and become as the birds and beasts.’62

For thinkers like Liang, S seki and Tagore, the challenges of the West were as much existential as geopolitical. What was good and bad about the old ways and the new ones proposed by the West? And was Europe’s modern civilization truly ‘universal’ and ‘liberal’, as its defenders claimed, or did it discriminate against non-white races? Could one stay loyal to one’s nation while importing ideas from the same Western countries that threatened that nation’s existence and survival? And how was one to define the new concept of the nation?

seki and Tagore, the challenges of the West were as much existential as geopolitical. What was good and bad about the old ways and the new ones proposed by the West? And was Europe’s modern civilization truly ‘universal’ and ‘liberal’, as its defenders claimed, or did it discriminate against non-white races? Could one stay loyal to one’s nation while importing ideas from the same Western countries that threatened that nation’s existence and survival? And how was one to define the new concept of the nation?

Varying geopolitical conditions and religious and political traditions would determine Asian responses and their timings. Long sequestered, the Japanese were able to borrow the tool-kit of modernity earlier and more comprehensively than any other Asian country. Emulating Russia and their Muslim peers in Egypt, the Ottoman Turks tried to embrace European military and administrative techniques in an attempt to make themselves invulnerable to European power. The Chinese went on lamenting their ‘backwardness’ vis-à-vis Europe late into the twentieth century.

A number of highly intelligent men turned to a traditionalist worldview grounded in fealty to the moral prescriptions of Islam, Confucianism and Hinduism. Some of the most innovative Asians sought an enlightened synthesis between their religious traditions and the European Enlightenment. Islamic modernists, for instance, called for a selective borrowing of European science, politics and culture, insisting that the Koran was fully compatible with modernity.

But in whatever these Asians did they all affirmed the extraordinary dominance of the West in almost every aspect of human endeavour in

the modern world. It was as though Asia’s vast empires, its venerable traditions and time-honoured customs had no defence against Europe’s purposive traders, missionaries, diplomats and soldiers. One by one, the Egyptians, the Chinese and the Indians revealed themselves as vulnerable, poorly fitted for a new modern world the West was making and which they had to join or perish. This is why the European subordination of Asia was not merely economic and political and military. It was also intellectual and moral and spiritual: a completely different kind of conquest than had been witnessed before, which left its victims resentful but also envious of their conquerors and, ultimately, eager to be initiated into the mysteries of their seemingly near-magical power.