Europe thinks she has conquered all these young men who now wear her garments. But they hate her. They are waiting for what the common people call her ‘secrets’.

A Chinese intellectual in André Malraux,

The Temptation of the West (1926)

The Temptation of the West (1926)

In 1889, while al-Afghani was stirring up anti-foreign agitation in Persia, an Ottoman frigate called the Ertu rul set sail for Japan on a goodwill mission. On board were some senior Ottoman military and civilian officials. It travelled for nine months, passing many ports in South and South-east Asia. Myths about the Ottoman Empire had long been in circulation in East Asia, and large numbers of Muslims turned out wherever the ship docked to witness the ‘man-of-war of the great Padishah of Stamboul’.1 Though slightly decrepit, the frigate seemed living proof of the potency of the last great Muslim ruler, the Ottoman sultan.

rul set sail for Japan on a goodwill mission. On board were some senior Ottoman military and civilian officials. It travelled for nine months, passing many ports in South and South-east Asia. Myths about the Ottoman Empire had long been in circulation in East Asia, and large numbers of Muslims turned out wherever the ship docked to witness the ‘man-of-war of the great Padishah of Stamboul’.1 Though slightly decrepit, the frigate seemed living proof of the potency of the last great Muslim ruler, the Ottoman sultan.

It also attested to the growing fascination with Japan among peoples suffering from what the Japanese journalist Tokutomi Soh , writing three years previously, had described as an ‘unbearable situation’:

, writing three years previously, had described as an ‘unbearable situation’:

The present-day world is one in which the civilized people tyrannically destroy savage peoples … The European countries stand at the very pinnacle of violence and base themselves on the doctrine of force. India, alas, has been destroyed. Burma will be next. The remaining countries will be independent in name only. What is the outlook for Persia! For China? For Korea?2

The outlook for Japan at least was clearer. The country, after a brief period of tutelage to the West, was breaking free of its masters, whereas the Ottomans, the Egyptian and Persians, while trying to modernize themselves, had slipped into a profound political and economic dependence on Western powers. The Ottoman frigate’s mission was evidence of how Asians everywhere were beginning to be transfixed by the amazingly rapid and unique rise of Japan.

The Ottoman officials were received by the Japanese political elite, including the prime minister and the emperor; they were taken to military parades and given tours of factories. Eager to match the West, and making good progress, the Japanese were prone to look down

upon their poor Asian cousins. In 1885, Fukuzawa Yukichi had proposed that since Asian countries were hopelessly backward and weak, Japan should ‘escape Asia’ and cast its lot in with ‘the civilized nations of the West’.3 This was the dominant mood of the Japanese elite at that time.

Still, there were some dissenting voices, too, about the real intentions of the ‘civilized nations of the West’ in Asia, and the Ottomans, a curious sight in Japan, managed to provoke some nascent fellow-feeling — the first pangs of what would later turn into full-blown pan-Asianism. Welcoming their Ottoman guests, Japan’s highest-circulation newspaper, Nichi Nichi Shinbun, expressed sympathy for a country that Europeans had subjected to

blatant outrages … The unjust and overbearing system of extraterritoriality was first practiced on them. Their country has yet to be able to escape from those shackles. Europe then extended these practices to the other countries of the East. Our country, too, suffers from this disgrace. The Turks are Asians like us … And so, they’ve come to us and communicated their friendship.4

When on its return journey the Ertu rul collided with a reef and sank, killing more than four hundred Turks on board, a wave of sympathy moved across Japan. Many Japanese donated generously to a fund set up for the survivors, and religious services for the dead were held across the country. Two Japanese warships took the remaining sixty-six Turks all the way to the Sea of Marmara. Sultan Abdulhamid himself received the Japanese naval officers in Istanbul and pinned medals on them.

rul collided with a reef and sank, killing more than four hundred Turks on board, a wave of sympathy moved across Japan. Many Japanese donated generously to a fund set up for the survivors, and religious services for the dead were held across the country. Two Japanese warships took the remaining sixty-six Turks all the way to the Sea of Marmara. Sultan Abdulhamid himself received the Japanese naval officers in Istanbul and pinned medals on them.

Japan’s reputation continued to rise in Istanbul throughout the 1890s and the next decade, especially after Japan achieved what the Ottomans had for decades tried unsuccessfully to do: a military pact with Great Britain in 1902, signalling its arrival as an equal in the Europe-ordained system of international relations. Abdulhamid, keen on stoking pan-Islamism, was disconcerted by the Japanese emperor’s rising status in Asia. Advised by al-Afghani, he politely declined a proposal from the Japanese emperor to send Muslim preachers to Japan. But he was also intrigued by how the Japanese had remained loyal to

their emperor while modernizing. In 1897, shortly after al-Afghani’s death, the sultan’s mouthpiece newspaper, published from Yildiz, editorialized that

The [Japanese] government, adorned with great intelligence and ideological firmness in progress, has implemented and promoted European [methods] of commerce and industry in its own country, and has turned the whole of Japan into a factory of progress, thanks to many [educational institutions]; it has attempted to secure and develop Japan’s capacity for advancement by using means to serve the needs of the society such as benevolent institutions, railways, and in short, innumerable modes of civilization.5

The Young Turks who raged against the Ottoman Empire’s inability to achieve parity with Western powers, and blamed their oldfangled monarchy for it, drew a different lesson from Japan’s alliance with Great Britain and its subsequent victory over Russia in 1905. ‘We should take note of Japan,’ the exiled Ahmed Riza wrote in 1905 in Paris, ‘a nation not separating patriotic public spirit and the good of the homeland from its life is surely such that [though] sustaining wounds, setting out against any type of danger that threatens its existence, it certainly preserves its national independence. The Japanese successes … are a product of this patriotic zeal.’6

For the Young Turks, soon to assume power and build a nation-state on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, Japan provided clear inspiration. These envious outside observers of Japan’s progress did not see the extreme violence of the country’s makeover. Nor did they notice the trends towards conformity, militarism and racism that were later to make Japan an ominously successful rival to Europe’s imperialist nations – by 1942 Japan would occupy or dominate a broad swathe of the Asian mainland, from the Aleutian Islands in the north-east to the borders of India, after booting out almost all the previous European masters in between. For many Asians in the late nineteenth century, the proof of Japan’s success lay in the extent to which it could demand equality with the West; and, here, the evidence was simply overwhelming for people who had tried to do the same and had failed miserably.

Its previous seclusion made Japan’s transformation between the years 1868 and 1895 particularly astonishing. The Ottomans had been nervously aware of Europe’s great intellectual ferment – the Enlightenment, the French Revolution – all through the eighteenth century. But the Japanese learnt of the French and American revolutions only in 1808, after closely questioning the few Dutch traders who had been allowed, following the expulsion of all foreigners from Japan, to retain an outpost at Deshima, a small island off Nagasaki.

In the 1840s, the British began to impose the first of many settlements designed to make China as dependent as India on a ‘free trade’ regime defined by Western powers. But even the news of their great neighbours’ woes travelled late to Japan. In 1844 the Dutch monarch addressed a formal proposal to the Japanese shogun, praising the universal virtues of free trade and gently pointing to China’s humiliation as an example of countries that had tried to buck the ‘irresistible’ worldwide trend. He received a brusque reply from the Japanese asking him not to bother writing again.7

Japan’s remarkably self-contained world was, however, nearing its end. The British, ensconced in India and coastal China, had long eyed Japan; British ships often sailed menacingly up the latter’s coast. But it was left to a new Western power, the United States, to force the issue.

Having completed its conquest of California in 1844, the United States looked across the Pacific for new business opportunities. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Tokyo (then called Edo) Bay with four men-of-war, and handed over a letter for the Japanese emperor from the American president which began with the ominous words, ‘You know that the United States of America now extend from sea to sea.’8 Denied an audience with the emperor, Perry retreated with subtle threats to return with more firepower if the Japanese did not agree to open their ports to American trade. They refused. He did as he said; and the Japanese succumbed.

During the long period of national isolation, many Japanese had studied with the Dutch traders and sailors based in Deshima; they turned out to be well informed about the strengths of Western barbarians – enough at any rate to know that resistance would be futile until Japan was internally strong. Much to the resentment of

Japanese nobles and the samurai, the Americans were granted trading rights and consular representation. Soon the British, Russians and Dutch were demanding the same for themselves.

The capitulation to foreign barbarians and the repeated violation of Japan’s long-preserved sovereignty incited great hostility, and eventually a full-scale rebellion, against the shogun. Meanwhile, the Americans pressed for more privileges, such as extraterritorial jurisdiction, and received them from an increasingly hapless old regime. Eventually, the shogunate collapsed under the strain of simultaneously appeasing foreigners and placating domestic xenophobia, and the Meiji Restoration began.

The westward expansion of America, and the rivalries of European powers, had abruptly begun to shape Japan’s politics. Japan looked as abject before Western soldiers, diplomats and traders as the Egyptians, Turks, Indians and Chinese had been. But what happened next broke radically with the pattern of dependence set by other Asian countries.

A generation of educated Japanese, some exposed to Western societies, came to occupy powerful positions in the Meiji Restoration. They recognized the futility of unfocused xenophobia, shrewdly analysed their own weaknesses vis-a-vis the West as scientific and technical backwardness, and urgently set about organizing Japan into a modern nation-state.

To this end, the emperor was brought out of seclusion and exalted as a symbol of the new religion of patriotism with its own shrines and priests. Buddhism was denounced, and Shinto, an assortment of beliefs and rituals, turned into a state religion, yet another glue to use for nation-building. Students were sent abroad; Japanese delegations, many of which included Japan’s future leaders and thinkers such as Fukuzawa Yukichi, travelled to the West. Foreign experts were welcomed in every realm, from education to the military. Western dress and hairstyles were adopted and Christian missionaries tolerated. The series of painstaking efforts culminated in a constitution in 1889 that, though exalting the emperor to divine status, tried to follow Western models in other details.

In apprenticing Japan to the West, the Meiji statesmen were lucky

to face fewer obstacles than their modernizing Ottoman or Egyptian peers had to deal with (and which the Chinese were yet to experience). Their powers of organization were helped by the fact that Japan, a small country, had an ethnically homogenous population. Groups such as the samurai and wealthy merchants did not resist modernization in the way that traditional elites in the Muslim world did. Indeed, the power of the supplanted elite, the samurai, could be redeployed in the task of national consolidation.

Japan’s economy had remained strong. So-called ‘Dutch’ learning – useful Western knowledge – was circulating in Japan well before Commodore Perry’s arrival. A strong local tradition of banker-merchants and an efficient tax-collection system meant that the Japanese economy was not crippled by foreign loans of the kind that banished Egypt, the first non-Western country to modernize, to the ranks of permanent losers in the international economy.

Moreover, the Meiji state never lost sight of its main objective: to radically revise the terms of Japan’s relationship with the West. If this meant accepting the superiority of Western civilization, as Fukuzawa Yukichi and others advocated, it seemed a small price to pay for national regeneration and admission to the exclusive club of powerful Western nation-states. For this to happen, however, the unequal treaties imposed on Japan by force of arms had to be revised. Japanese diplomats kept pleading, especially with the British who, of all the Western powers present in Japan, most vehemently opposed the withdrawal of their special concessions. The Japanese even resorted to flattery, presenting themselves as Anglophiles and the ‘civilized’ equivalent of the British in the East. Finally, after one failed attempt in 1886, which incited a backlash from patriotic Japanese, Japan persuaded the British in 1894 to agree to terminate extraterritorial rights in five years’ time.

That same year Japan went to war with China. The cause was Korea, which both countries sought to dominate. It was the first test of Japan’s modernity, and also, as Tokutomi Soh frankly put it, a golden opportunity for Japan to ‘build the foundation for national expansion in the Far East … to take her place alongside the other great expansionist powers in the world’.9 The brisk rout of Chinese naval and land forces not only resoundingly proved the sturdiness of

Japan’s military and its industrial and infrastructural base. It also showed that, as Soh

frankly put it, a golden opportunity for Japan to ‘build the foundation for national expansion in the Far East … to take her place alongside the other great expansionist powers in the world’.9 The brisk rout of Chinese naval and land forces not only resoundingly proved the sturdiness of

Japan’s military and its industrial and infrastructural base. It also showed that, as Soh put it, ‘civilization is not a monopoly of the white man’.

put it, ‘civilization is not a monopoly of the white man’.

Overtaxed Japanese peasants had already paid a huge price for Japan’s modernization along Western lines, a process inherently brutal for the weakest everywhere. It was now the turn of the Chinese. The ‘real birthday of New Japan’, the writer Lafcadio Hearn, then living in Japan, wrote, ‘began with the conquest of China’.10 Tokutomi Soh hailed a ‘new epoch in Japanese history’. White men had regarded the Japanese, Soh

hailed a ‘new epoch in Japanese history’. White men had regarded the Japanese, Soh complained, as ‘close to monkeys’.11 Now

complained, as ‘close to monkeys’.11 Now

We are no longer ashamed to stand before the world as Japanese … Before we did not know ourselves, and the world did not yet know us. But now that we have tested our strength, we know ourselves and we are known by the world. Moreover, we know that we are known by the world.12

Closely following the practices of ‘civilized’ nations, Japan forced China to pay a huge indemnity, to open riverside towns deep in the hinterland as treaty ports, and to cede the island of Taiwan (then called Formosa). As part of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, Japan even appropriated a bit of mainland China, the Liaotung Peninsula, before Russia, France and Germany prevailed upon the country to be less punitive and hand it back.

The return of the Liaotung Peninsula under Western pressure provoked more discontent among Japanese patriots (exacerbated when Russia forced the Qing emperor to lease Port Arthur (now Dalian) on the peninsula to the Russian navy, which caused a rift with Japan that led to the Russo-Japanese War in 1904). There was no question now of Japan remaining subordinate to Western powers on its own territories. The treaties were revoked, and in 1902, nearly half a century after the Ottoman Empire first tried to climb on to the international stage on the back of the greatest European power, the Japanese concluded an alliance with the British Empire.

Tokutomi Soh , already Japan’s most respected journalist, was on a ship en route to the Japanese military base at Port Arthur when he

learnt of the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Soh

, already Japan’s most respected journalist, was on a ship en route to the Japanese military base at Port Arthur when he

learnt of the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Soh had long been convinced that Japan, a small country with few resources of its own for modernization, had to expand its territories, a ‘matter of the greatest urgency’, and for that she had to ‘develop a policy to motivate our people to embark upon great adventures abroad’ and ‘solve the problem of national expansion without delay’. Now – April 1895 – it seemed possible. The news put him in a buoyant mood.

had long been convinced that Japan, a small country with few resources of its own for modernization, had to expand its territories, a ‘matter of the greatest urgency’, and for that she had to ‘develop a policy to motivate our people to embark upon great adventures abroad’ and ‘solve the problem of national expansion without delay’. Now – April 1895 – it seemed possible. The news put him in a buoyant mood.

It was the first time he had left Japan. In Port Arthur, he later recalled,

spring had just arrived. The great willows were budding; the flowers of North China were at the height of their fragrance. Fields stretched out before the eye; a spring breeze was blowing. As I travelled about and realized that this was our new territory, I felt a truly great thrill and satisfaction.13

Soh ’s joys of new ownership died quickly as he received news of Japan being forced to give up the territory by Western countries. ‘Disdaining’, he later wrote, ‘to remain for another moment on land that had been retroceded to another power, I returned home on the first ship I could find.’

’s joys of new ownership died quickly as he received news of Japan being forced to give up the territory by Western countries. ‘Disdaining’, he later wrote, ‘to remain for another moment on land that had been retroceded to another power, I returned home on the first ship I could find.’

Soh took a handful of gravel back to Japan to remind him of the pain and humiliation he had suffered. It was clear that, as he lamented, ‘the most progressive, developed, civilized, and powerful nation in the Orient still cannot escape the scorn of the white people’. And, having been ‘baptized into the gospel of power’,14 as he wrote bitterly, Soh

took a handful of gravel back to Japan to remind him of the pain and humiliation he had suffered. It was clear that, as he lamented, ‘the most progressive, developed, civilized, and powerful nation in the Orient still cannot escape the scorn of the white people’. And, having been ‘baptized into the gospel of power’,14 as he wrote bitterly, Soh , the champion of individual rights and freedoms, would now become a loud advocate of Japan’s imperialist expansion in Asia, which, he hoped, would ‘break the worldwide monopoly and destroy the special rights of the white races, eliminate the special sphere of influence and the worldwide tyranny of the white races’.15

, the champion of individual rights and freedoms, would now become a loud advocate of Japan’s imperialist expansion in Asia, which, he hoped, would ‘break the worldwide monopoly and destroy the special rights of the white races, eliminate the special sphere of influence and the worldwide tyranny of the white races’.15

The return of Japan’s spoils of war under Western pressure was no consolation to many Chinese; the damage to their self-esteem had already been done. The question for them was whether it would spur any meaningful attempt at self-strengthening in China.

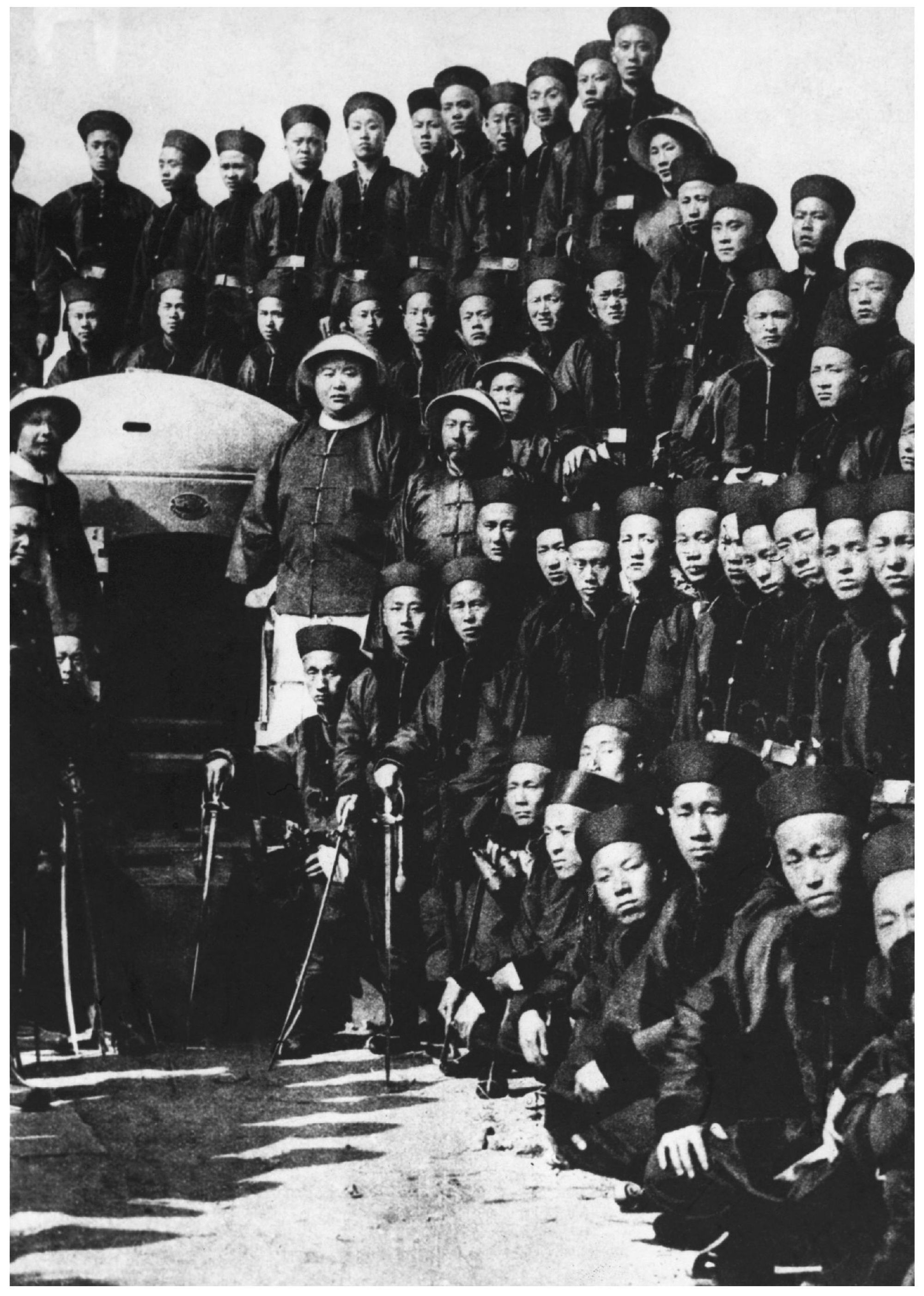

Shortly after China’s defeat in early 1895, Japanese troops stopped and searched a Chinese steamer in the North China Sea. Such

infringements of China’s sovereignty had become routine then, but by one of the strange accidents of history there were among the many students on board a twenty-two-year-old called Liang Qichao and his mentor, Kang Youwei, then aged thirty-seven, both travelling to Beijing to sit the imperial examinations for China’s civil service.

Liang was to become China’s first iconic modern intellectual. His lucid and prolific writings, touching on all major concerns in his own time and anticipating many in the future, inspired several generations of thinkers including the much younger Mao Zedong. A restless intellectual seeker, Liang combined his Chinese classical learning with a great sensitivity to Western ideas and trends. And his life, and its many intellectual phases, manifested more profound dilemmas than many other Chinese thinkers, bolder but shallower than Liang, faced. It would be woven tightly through all major events and movements in China over the next three decades.

The exams selected the men of ‘virtue’ whom Confucian classics called upon to be responsible for the social order. Success in them was the passport to status and prestige in China. There were more men passing them than there were government jobs, but Liang and Kang could still look forward to membership of an elite culture, and good jobs in teaching or business if not necessarily high positions with the government. However, they had other things on their minds than personal advancement.

Hailing from scholar-gentry families near Canton (Guangzhou) in Guangdong, the Chinese province most exposed to Western aggression, they were both patriotically concerned about the fate of China, and seethed at its ignorance and helplessness in the face of the Western challenge. Early in the nineteenth century, Indian intellectuals had begun to receive – and transform – the ideas of Rousseau, Hume, Bentham, Kant and Hegel; by the middle of the century, they were following the fortunes of Mazzini and Garibaldi. But most Chinese in the nineteenth century did not know of the existence of Western countries, let alone of their internal revolutions.

China came into contact with the West only at the port of Canton, which, closely regulated and strictly commercial, was never likely to turn into the transmitter of Western knowledge that Deshima became for the Japanese. A large part of the problem was that for too long

China had, Liang wrote in 1902, ‘looked on its country as the world’, and regarded the rest as barbarians.16 Liang himself first learnt about China’s lowly position in the world when in the spring of 1890 he came across books in Chinese on the West in Beijing.

In 1879, Kang Youwei had been similarly surprised while visiting Hong Kong. Awestruck by the British-run city’s efficiency and cleanliness, he realized that educated Chinese like himself ought not to look down upon foreigners as barbarians. Further reading in Western books convinced him that the Chinese status quo was unsustainable, and, after a brief flirtation with Buddhism, Kang resolved to rejuvenate the social ideals of Confucianism.

Liang was one of the bright young students Kang had gathered around himself in a Confucian temple in Canton to both prepare for the imperial examinations and to reinterpret the Confucian canon as a call to social and educational change. Kang had already spent a decade importuning the Qing court in Beijing with letters and memos about the urgency of reforms. Experiencing Japanese arrogance on board his ship to Beijing now hardened his conviction, and loosened his tongue. At the risk of lèse-majesté, Kang now told his fellow students that China had degenerated so much that it resembled Turkey, another once-confident and now-feeble country carefully maintained in its infirmity by exploitative foreigners.

This, if anything, was an optimistic diagnosis. The European ambassadors in Istanbul may have been intolerably interfering in Turkey’s domestic affairs, but they exercised none of the brute force that their counterparts in Beijing did. The Ottoman sultan never had to scurry into hiding to escape their wrath; Istanbul was not besieged, nor its grandest imperial palace burnt to the ground.

From the late 1830s (just as the Tanzimat reforms were being set in motion in Istanbul), to the Second World War, China was bullied and humiliated on a vast scale. And it was more shocking for the Chinese because they had lived with the illusion of power and self-sufficiency for much longer than the Ottomans. ‘Our country’s civilization’, Liang Qichao pointed out in 1902, ‘is the oldest in the world. Three thousand years ago, Europeans were living like beasts in the field,

while our civilization, its characteristics pronounced, was already equivalent to theirs of the middle ages.’17

This wasn’t just some cultural defensiveness. China could trace its culture back 4,000 years, and political unity to the third century BC. If the Han and Tang dynasties had supervised the writing of China’s historical classics and its greatest poetry, the Song had built a network of roads and canals across China. China led the world in science and arts, and in the development of a sophisticated government bureaucracy selected through competitive examinations. Recruiting its bureaucrats from a provincial gentry that was schooled in Confucian classics, the Chinese imperial state relied less on coercion than on the loyalty of local elites across China.

As in Islamic countries, a literary culture and a morality derived from canonical texts gave Chinese civilization an extraordinary coherence, and made it the most influential cultural model for neighbours such as Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Western travellers, many of them Jesuit missionaries, brought back highly coloured descriptions of self-possessed, sophisticated and ethical followers of Confucius, turning such Enlightenment philosophers as Voltaire and Leibniz into ardent Sinophiles and nascent European consumers into connoisseurs of all things Chinese.

Contrary to the general picture of the decline of Asia and the rise of the West, the Chinese economy was buoyant in the eighteenth century, developing its own local variations and with trade links across South-east Asia. Silk, porcelain and tea from China continued to be in great demand in Europe (and in the American colonies) even though in 1760 the Chinese confined all Western traders to the port city of Canton. Tribute-paying neighbours as near as Burma, Nepal and Vietnam (and as far away as Java) upheld Beijing’s solipsistic view that the Chinese emperor, presiding over the central kingdom of the world, had the right to rule ‘all under heaven’. The Qing Empire, founded by nomadic warriors from north-east China, or Manchuria, in 1644, was still expanding its territory in the eighteenth century. The last great Manchu emperor, Qianlong, personally supervised the annexation of Xinjiang and parts of Mongolia, and the pacification of Tibet.

The Manchus were foreigners, but they hadn’t radically disrupted

China’s traditional socio-political order, which, unparalleled anywhere in the world, had been perfected over centuries by several imperial dynasties using the teachings of the sixth-century BC sage Confucius. Far more long-lasting than Islam, Confucianism had underpinned Chinese government and society for two millennia; its values of ren, yi, xiao and zhong, imperfectly translated as ‘benevolence’, ‘propriety’, ‘filial piety’ and ‘loyalty’, prescribed the correct modes of behaviour and action in both private and political life.

As the Mongols had done before them with Muslim countries, the Manchus did not impose their ways upon the conquered population of Han Chinese. Rather, they tried to persuade the latter that they were not uncouth upstarts from the north. They upheld Confucianism as the source of social and personal values, with the Kangxi and Qianlong emperors presiding over a major reinterpretation of Confucian classics. Confucian ideas intermingled with and were often overlaid by other Chinese religious traditions. But they remained the basis for the imperial examinations that led so many Chinese to seek service with the state’s vast bureaucracy, and they had long contributed to China’s extraordinary political unity and ideological consensus.

China’s population expanded rapidly during Qianlong’s long reign, putting pressure on the land. Towards the end of his reign, a series of local rebellions and economic crises revealed that all was not well with the Qing Empire. Corruption among Manchu nobles had grown, and partly in response, revolts, often of a millenarian cast, erupted across north China. There were more such shocks to come in the nineteenth century, especially the Taiping rebellion, which was led by an eccentric sect fired by Christian millenarianism. But the panoply of omnipotence was carefully maintained throughout these crises: China remained the universe, with everyone else on its insignificant periphery. The illusion could not survive.

Even before the Opium War, Western powers had begun to nibble at the edges of the Qing Empire, annexing the territories that the Manchus had brought into the tributary system. Beginning in 1824, after many hard battles the British subdued Burma, and made it a province of their Indian empire in 1897. In 1862, while the Qing were busy fighting the Taiping rebels, France overran southern Vietnam; it

invaded the north of the country in 1874, and then, in 1883, announced the old kingdom of Annam in central Vietnam to be its protectorate. The Chinese resisted, and in the war that ensued the French destroyed much of the Chinese navy.

As in the Ottoman Empire, military losses to Western powers made Chinese bureaucrats call for urgent ‘self-strengthening’. Contrary to the Western caricature of the ‘Confucian’ mentality that was not amenable to modernization, the Chinese were quick to learn the lesson from their defeats. Two years after witnessing the total defencelessness of Chinese coastal cities during the First Opium War, Lin Zexu, the former imperial commissioner at Canton, wrote a private letter to a friend underlining the need for adopting modern weapons technology. ‘Ships, guns, and a water force are absolutely indispensable. Even if the rebellious barbarians had fled and returned beyond the seas, these things would still have to be urgently planned for, in order to work out the permanent defence of our sea frontiers.’18

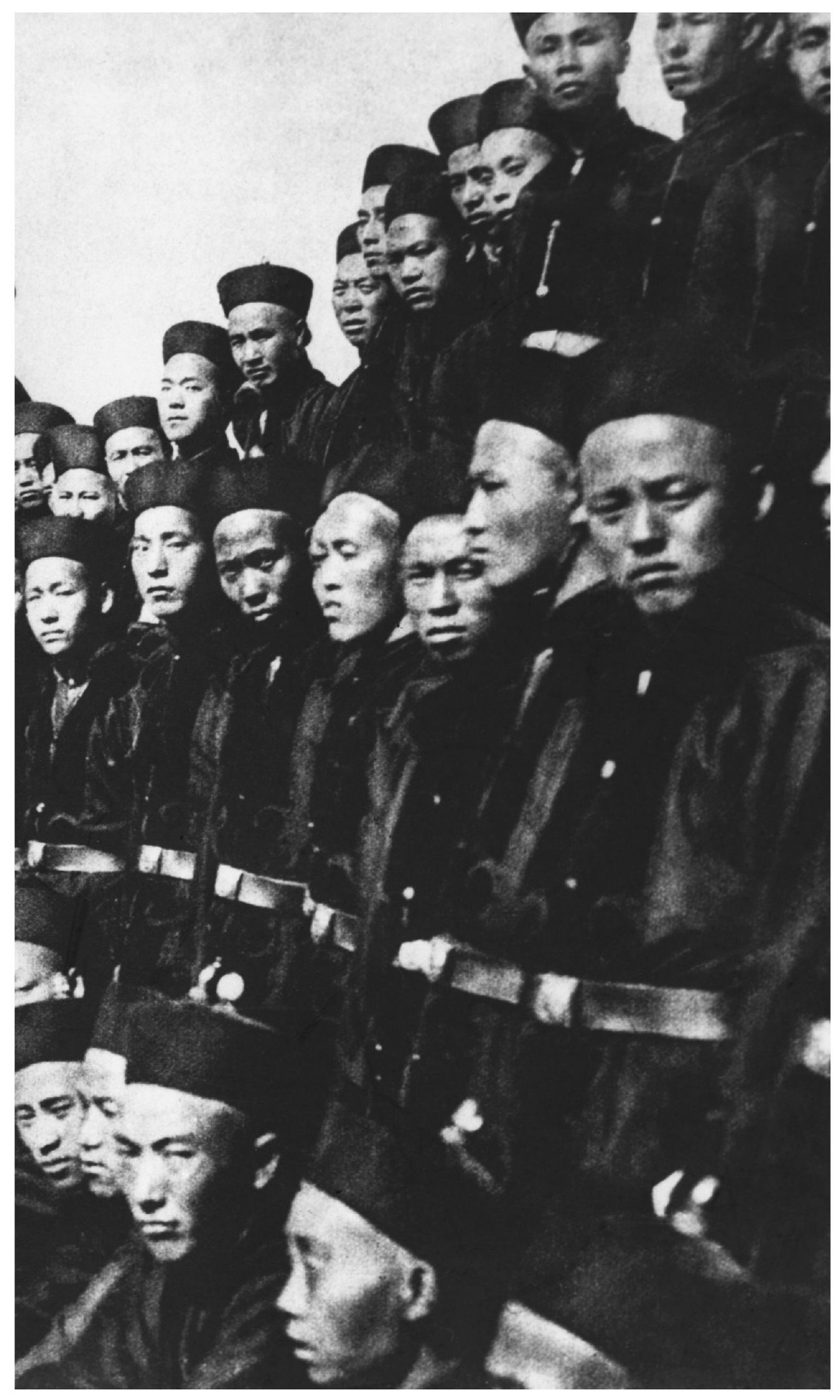

Another Chinese scholar-official, Li Hongzhang, who led one of the victorious Qing armies against the Taiping rebels, managed to persuade the conservative court to set up factories and dockyards for the production of modern weapons and ships, regulate relations with foreign powers, open legations in the capitals of Europe, America and Japan, and send students abroad. Li also helped set up the country’s first coal mines, telegraph networks and railway tracks in the 1870s.

China’s infant industries faced the same kind of insuperable hurdles that free-trading Britain had imposed on Egypt and Ottoman Turkey; they could not compete with European, American and Japanese manufacturers. Unlike countries directly occupied by European powers, this was the situation of the ‘semi-colony’ in which, as Liang Qichao pointed out in 1896, ‘a hundred times more than Western soldiers, Western commerce weakens China’.19 Still, with Li Hongzhang’s help, a modicum of industrial manufacturing soon became visible with the country’s first cotton mills and iron works.

British businessmen, who wished to prop up the ailing Manchus as much as they could, were eager to help. Dining with some of them in Hong Kong in 1889, Rudyard Kipling did not think a modernized China was a good idea. He deplored the men who were doing their best to ‘force upon the great Empire all the stimulants of the

West – railways, tramlines, and so forth. What will happen when China really wakes up?’20 Kipling was right to worry; but this China still lay a century ahead. For now, as the Ottomans had learnt, piecemeal modernization was revealed as inadequate – in 1884 the French took only an hour to destroy the Chinese navy’s arsenal in Fuzhou that Li Hongzhang had helped set up.

The smallest move to imitate their Western adversaries provoked a backlash from the most powerful conservative forces in the country, the scholar-gentry, who worried about the loss of their judicial and moral authority over citizens exposed to European modes of thinking and action. In a country as large and old as China, the shock of the West did not really travel deeply enough to begin to force change until the last decade of the century. The intellectual world of the scholar-gentry, defined by strict adherence to Confucian values and absolute loyalty to the emperor, remained more or less unimpaired. Self-made young men in the provinces, such as Sun Yat-sen, had begun to dream of the overthrow of the Manchus, but for much of the scholar-gentry there was no question of even slightly modifying the imperial system which was presided over by the politically reactionary and fiscally profligate Dowager Empress Cixi, who spent nearly the entire national treasury on building a new Summer Palace.

China, which had entered the nineteenth century with a favourable balance of trade, was running massive foreign debts at the end of it. Up to a quarter of government revenue went into paying foreign debts and indemnities. Foreigners administered virtual mini-colonies within sixteen cities: as in Ottoman Turkey and Egypt, they were protected from the local police and courts even for the gravest crimes.

The harsh lessons of the international system could no longer be kept at bay, not after neighbouring Japan, which most Chinese saw as inferior, trounced China in battle in 1895. At the Chinese port city of Weihaiwei, the Japanese, creeping up overland from the rear, turned China’s own guns on the Chinese fleet in the bay. As Japan secured the choicest spoils of war in the subsequent Treaty of Shimonoseki with China, imperialists elsewhere were further emboldened. The Western scramble for Africa and South-east Asia was already under way. Qing China seemed an even easier picking.

Britain forced China to lease it Weihaiwei and the New Territories

north of the island of Hong Kong. France established a base on Hainan Island and mining rights across China’s southern provinces. Germany occupied part of Shandong province. Even Italy, a latecomer to Chinese affairs and expansionism in general, demanded territory (although it was successfully rebuffed). The United States did not participate in this dismemberment of the Middle Kingdom, the slicing of the Chinese melon as it came to be called. But, reaching the limits of their own westward expansion and urgently seeking foreign markets, the Americans announced in 1900 an ‘Open Door’ policy that cannily reserved the profits of an informal empire of free trade for foreigners while leaving the costs and responsibilities of governance to the Chinese.

By 15 April 1895, when the terms of the treaty with Japan were announced, Liang Qichao had reached Beijing with Kang Youwei and hundreds of other candidates to compete for the two hundred available degrees. The news, which spread rapidly from the coastal cities to the hinterland, wounded the Chinese in a way that the Opium War had not. ‘Previously young Chinese people paid no attention to current events,’ a provincial reader of newspapers later recalled, ‘but now we were shaken … Most educated people, who had never before discussed national affairs, wanted to discuss them: why are others stronger than we are, and why are we weaker?’21 It was brutally clear that two decades of ‘self-strengthening’ reforms undertaken by the Qing – the building of arsenals and railways – had amounted to nothing. For the first time, China was being forced to give up an entire province, Taiwan, to a foreign power, in addition to paying the largest indemnity ever and renouncing suzerainty over Korea, its last major tributary state.

Enraged by China’s abasement, an activist called Sun Yat-sen organized an uprising in Guangzhou with the help of money raised from overseas Chinese communities. His plot was discovered and the uprising aborted by the Qing authorities. Sun was forced to flee to Japan, and then on to London, where he was to meet many other nationalists and radicals from India, Egypt and Ireland.

Kang, who had also witnessed the shaming defeat of China by France in 1884, wasn’t about to try something as extreme as overthrowing the Qing Empire. Still, the extreme humiliation inflicted by Japan, a country which, gallingly, had received its high civilization from China, forced Kang to do something unprecedented in the history of politics in Qing China. He organized a meeting of the examinees, the young men aspiring to be the country’s next elite, and petitioned the emperor, the young and weak Guangxu who was in thrall to the dowager empress, his aunt, to reject the treaty.

The drama of this is easily missed. As a humble aspirant to the civil service, Kang had no locus standi; and his long petition, which called for the total transformation of the economic and educational systems, aimed at nothing less than a revolution from above – a Tanzimat-style shake-up of institutions. Extraordinarily, his petition reached the emperor, who read it and forwarded a copy to the dowager empress. Nothing came of it, and conservative elements at the court eventually forced Kang out of Beijing. But he had set a precedent by organizing a meeting and authoring a mass petition in a place where such things were unheard of; he had initiated nothing less than what Liang later described as the first mass movement in Chinese history.22

Kang now threw himself into propaganda and organization work, establishing study-societies for the edification of the scholar-gentry across China with names like ‘Society for the Study of National Strength’. Often helped by politically congenial local governors, these voluntary organizations set up libraries, schools and publishing projects that aimed to make the Chinese ‘people’, a hitherto unheard-of category, more responsive to the emperor, and active participants in public life.

Liang, who had laboriously made copies of the long petition submitted to the emperor, was freshly energized. Visiting Shanghai in 1890 – the same year he met Kang Youwei in Canton – Liang had come across an outline of world geography and translations of European books. His horizons expanded even more when in 1894 he acted as the Chinese secretary to a British missionary, who translated a then popular book, a booster-ish history of Europe’s progress.

The next year Liang became the secretary of the Beijing branch of a study-society, and started a newspaper with the help of private

donations. When imperial censors closed it down, he went to Shanghai and started another paper in 1896 called Xiwu Bao (‘Chinese Progress’). It lasted for a mere two years. However, it was read widely for its articles on the urgency of industrialization and modern education, many of them authored by Liang himself, and it made Liang the most influential journalist in China.

Nearly two decades had passed since the press became, with al-Afghani’s help, an instrument for aspiring modernizers in the Arab world. Nearly a century before, a public sphere for debate and discussion had opened up in India. China was starting relatively late, and Liang tried to make up for lost time. In article after article, he stressed the urgency of political reform, which he held to be more important than technological change; the key to this reform was the abolition of the old imperial examinations and the establishment of a nation-wide school system that created confidently patriotic citizens for the New China. For,

If there is no moral culture in the schools, no teaching of patriotism, students will as a result only become infected with the evil ways of the lower order of Westerners and will no longer know they have their own country … The virtuous man, then, will become an employee of the foreigners in order to seek his livelihood; the degenerate man will become, further, a traitorous Chinese in order to subvert the foundations of his country … In the state of disrepair to Chinese armaments, we see one road to weakness; in the stagnation of culture, a hundred roads.23

Calling for a severe modification of existing institutions, Liang was not blind to the appeal of Confucianism, or that of the traditional structure of Chinese society and state in which the individual was loyal to his family and an elite of scholar-officials mediated between the imperial court and the population. He still hoped to rouse the scholar-gentry first to the tasks of nation-building. Addressing scholars in Hunan in 1896, he said, ‘Now you gentlemen, who wear the scholar’s robes and read the writings of the sages, must find out whose fault it is that our country has become so crippled, our race so weak, our religion so feeble.’24 In fact, he was as loyal as Kang at first to the ruling Qing order; the idea of overthrowing it, which had already energized Sun Yat-sen, did not feature in his political plans for the

future. But his intellectual trajectory, though initially hewing close to Kang’s, was showing signs of divergence.

As Liang began to see, China’s old system of monarchy had become a force for the status quo and intellectual and political conformity; it was capable now of nothing more than maintaining the ruling dynasty in power. The state needed popular consent from those it ruled, and only a well-educated and politically conscious citizenry could create the kind of collective dynamism and national solidarity essential to China’s survival in the dog-eat-dog world of international geopolitics.

Never explicitly named, ideas of popular sovereignty and nationalism bubbled beneath the surface of Liang’s writings for Xiwu Bao, and his teachings at a reformist school in Hunan (where he went in 1897 after leaving Xiwu Bao over a disagreement with its manager). In the beginning, Liang phrased them through invocations of Chinese tradition: ‘Mencius says that the people are to be held in honour, the people’s affairs may not be neglected. The governments of present-day Western states come near to conformity with this principle, but China alas, is cut off from the teachings of Mencius.’25

Liang was beginning to realize that, however admirable in itself, the old Chinese order was not capable of generating the organizational and industrial power needed for survival in a ruthless international system dominated by the nation-states of the West. Though educated traditionally, he had already begun to drift away from the narrow world of Chinese scholarship and imperial service. And he was to move far from the ideas of his great teacher and mentor. Kang saw himself as a Confucian sage with a moral mission to rejuvenate China. With this outcome in mind, he didn’t hesitate to reformulate Confucianism itself. Liang would follow a different path for much of his life before returning to some of the ideals of his youth.

In retrospect, and especially from the outside, Confucianism seems like an abstract philosophy or a set of beliefs imposed upon the Chinese people by the state – something easily and voluntarily discarded. But its roots in China were deep and it provided by general consensus the religious and ideological underpinning of China’s political order. It upheld the principle of kingship; the only political community it

envisaged was the universal empire, ignoring the city-state and the nation-state that were central to the Western tradition. And it prescribed the duties of the state as the maintenance of Confucian moral teachings, rather than political and economic expansion.

So for Kang, as for many other reformers of the late Qing period, Confucian teaching was beyond reproach. Even Liang, who would depart radically from his mentor, did not cease to see himself as an embodiment of a unique repository of cultural ideals and beliefs – one that defined China as much, if not more, than Christianity defined the West. Confucianism’s extraordinary continuity partly ensured this reverence. The social and ethical norms it prescribed for both the ruler and the ruled seemed essential to maintaining order. Peasant uprisings in the past had challenged the Confucian system and its main representatives, the scholar-gentry, but they could be explained away as revolts against Chinese rulers and imperial bureaucrats who had betrayed Confucian teachings.

Still, the new external threat posed by Western capitalism and Christianity was not explained away so easily. Indeed, as these pressures intensified by the 1850s, many imperial bureaucrats defensively put forward an extremely conservative view of Confucian belief and practice: one that preserved their moral and judicial authority. (A similar hardening of religious and ethical belief-systems was also under way in India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the Muslim world.)

This is why both Kang and Liang were nothing less than radical in their demand for political innovation and public participation in government. In their milieu, the mastery of Confucian classics and success in traditional exams were what brought power and respect to the literati. It was their task to uphold the dictates of Confucian morality, which emphasized a hierarchical society held together by mutual moral obligations. This elite with its highly developed sense of social responsibility, refined manners and etiquette provided the natural leaders of communities in villages and towns across China. Confucian teaching provided the content, for instance, of the civil service examination: the so-called ‘eight-legged essay’, which had decided the outcome of the examinations for centuries, was to be written on one of the themes from the canonical Confucian writings, the ‘Four Books’.

Such formalist education was clearly ill suited to the modern age, and the Confucian stress on private morality was not up to the task of creating the public-spiritedness needed for a new nation. Writing in 1895, the writer and translator Yan Fu described the differences between China and the West as stark:

China values the Three [family] Bonds most highly, while the Westerners give precedence to equality. China cherishes relatives, while Westerners esteem the worthy. China governs the realm through filial piety, while Westerners govern the realm with impartiality. China values the sovereign, while Westerners esteem the people. China prizes the one Way, while Westerners prefer diversity … In learning, Chinese praise breadth of wisdom, while Westerners rely on human strength.26

It was clear to Kang that China could survive only by absorbing some of the virtues of the West. At the same time, Confucianism had to be maintained in some form in order to preserve the political and social basis of China. In other words, Confucianism had to be reinvented in order to save it.

Similar anxieties had afflicted many of the scholar-gentry as the pressures from the West exposed the fragility of the Qing Empire, and there was a large enough audience for Kang by the end of the nineteenth century. Still, how was one to break with something so revered and rooted in Chinese soil as Confucianism? How was one to reinterpret something so symbolic of order and continuity as a philosophy of social change?

Kang was like the conservative reformers in the Muslim world for whom the verities of Islam could not be fundamentally challenged, or even like Gandhi, who saw Indian traditions as a perfectly adequate resource for a new nation. They all faced the task of having to generate a new set of values that ensured survival in the modern era while respecting time-honoured traditions – of appearing loyal to their nation while borrowing some of the secrets of the West’s progress.

Fortunately, in the intellectual free-for-all that characterized this moment of transition to new ideas of nation and people, the scope for radical interpretation of tradition was great. Confucianism, in particular, had been marked by competing schools of thought. Reviving an old controversy among Confucian scholars, Kang attacked the prevailing

school of Confucianism as fake, claiming that the authentic teachings of Confucius were contained in the New Text School that had been dominant during the former Han dynasty.

Kang set out his ideas in two books, which Liang described as a ‘volcanic eruption’ and an ‘earthquake’ in the world of Confucian literati. 27 Kang, Liang later said, was the ‘Martin Luther’ of Confucianism. But Kang saw himself as entering something more than a scholastic or theological dispute with other Confucianists. As with Gandhi and the Bhagavadg t

t , and al-Afghani and the Koran, Kang was aiming to make political reform and mass mobilization a central concern of Confucius himself, in order to make his ideas relevant to China’s present and future and give sanction to the reformist aspiration for scientific and social progress. Thus, in Kang’s reading of the Confucian classics, emancipation of women, mass education and popular elections came to appear central concerns of the sixth-century BC sage.

, and al-Afghani and the Koran, Kang was aiming to make political reform and mass mobilization a central concern of Confucius himself, in order to make his ideas relevant to China’s present and future and give sanction to the reformist aspiration for scientific and social progress. Thus, in Kang’s reading of the Confucian classics, emancipation of women, mass education and popular elections came to appear central concerns of the sixth-century BC sage.

Kang was to go even further, offering a utopian vision of an inevitable universal moral community, where egoism and the habit of making hierarchies would vanish, and which would realize the Confucian idea of ren (benevolence). But this would lie in the future, after the Chinese nation had pulled itself together. For now, Kang was content to emphasize the need for institutional reform within China, for the country, as he saw it, faced a challenge from the West that was not only political but also cultural and religious. The West not only endangered the Chinese state; it also threatened Confucianism. This anxiety motivated all his campaigns for a nationwide school system or a constitutional monarchy or military academies. Perhaps influenced by the exalting of Shintoism as a state religion in Japan, Kang would even propose that Confucianism be made a state religion to combat the effect of Christianity, with local shrines turned into temples to the ‘important sage’.

By the 1890s, many voluntary organizations in coastal China were propagating the religion they called ‘Confucianism’, and Kang converted many scholar-gentry to Western political values by making them seem part of Confucian traditions. The challenge he posed to the traditional political order with his arsenal of traditional political theory was to prove momentous; it was the beginning of a new

radical phase in China’s history, in which all the old verities would be questioned and overturned.

Certainly there was a range of reformist ideas thrown up by the intellectual ferment of China in the 1890s. While Liang was publishing his periodical in Shanghai, Yan Fu was bringing out a popular newspaper and magazine from Tianjin, where he was president of the naval academy. Yan, who had studied in England for two years, was among the handful of Chinese to have experienced the West at first hand. His translations of Herbert Spencer, John Stuart Mill, Adam Smith and T. H. Huxley first introduced many Chinese thinkers, including Liang, to contemporary Western philosophers and, most importantly, to the quasi-Darwinian explanation of history as the survival of the fittest.

Like many intellectuals in Asia, Yan awoke with a shock to the threat from Western imperialists. ‘They will enslave us and hinder the development of our spirit and body,’ he wrote in 1895. ‘The brown and black races constantly waver between life and death, why not the 400 million Yellows?’ Like many of his Asian peers, Yan Fu became a Social Darwinist, obsessed with the question of how China could accumulate enough wealth and power to survive. As he wrote, ‘Races compete with races, and form groups and states, so that these groups and states can compete with each other. The weak will be eaten by the strong, the stupid will be enslaved by the clever … Unlike other animals, humans fight with armies, rather than with teeth and claws.’28 ‘It is’, he added, ‘the struggle for existence which leads to natural selection and the survival of the fittest – and hence, within the human realm, to the greatest realization of human capacities.’29

Yan believed that the West had mastered the art of channelling individual energy and dynamism into national strength. In Britain and France people thought of themselves as active citizens of a dynamic nation-state rather than, as was the case in China, as subjects of an empire built upon old rituals. Like people in the West, Yan Fu asserted, the Chinese people had to learn to ‘live together, communicate with and rely on each other, and establish laws and institutions, rites and rituals for that purpose … We must find a way to make everyone take the nation as his own.’30 Yan’s ideas, which seemed at odds with Confucian notions of cosmic harmony, and helped introduce such

words as ‘nation’ and ‘modern’ into the Chinese vocabulary in the 1890s, would not encounter much resistance among several generations of Chinese intellectuals, including, most prominently, Liang Qichao. In fact, they were quickly embraced, for they perfectly described the precarious situation China found itself in.

Compared to Yan Fu, a figure like Tan Sitong was a traditionalist philosopher. As a young man in Beijing in 1895, Tan, the idealistic son of a high official, sought out Kang Youwei. Kang was then in Canton, and it was his chief assistant Liang who introduced and converted Tan to Kang’s worldview, besides introducing him to Buddhism. Tan, one of the most original minds of his generation, went further than his mentors, advocating republicanism rather than a reformed monarchy, and nationalism in place of loyalty to the Manchus. Not unlike Gandhi, Tan posited the need for constant moral action and awareness, expanding the Confucian notion of the good as something that combined sensitivity to social ethics in the present and future with a personal struggle for self-perfection.

For a few weeks at least, this was not all theorizing in the sad tea-houses of Beijing. In early 1898, the dowager empress allowed the twenty-three-year-old Guangxu to rule properly as emperor, and suddenly Kang’s and Liang’s many study-societies, newspapers, schools and behind-the-scenes discussions with reformers at the imperial court seemed to bear fruit. The newly empowered emperor, who had already noted one petition by Kang in 1895, turned to him for help with reform. Kang responded with several spirited essays, including one on the success of Meiji Japan, and another on the helplessness of India under British rule. ‘Reform and be strengthened,’ he wrote, ‘guard the old and die.’31

Kang was invited to the Forbidden City. An extraordinary five-hour-long meeting with the emperor ensued. It was followed in June by a barrage of imperial edicts ordering bold reforms in almost every realm, from local administration and international cultural exchange to the beautification of Beijing. For about a hundred days, Kang, Liang and Tan Sitong became as powerful as any group of like-minded intellectuals elsewhere had been since the French Revolution.

A decree made Liang, who had yet to pass the imperial examinations,

the director of the translation bureau. More surprisingly, his newspaper Xiwu Bao was turned into an official organ. Liang and Tan accompanied Kang to meetings with the emperor at his palace where they dropped all ritual and ceremony, planning reforms while lounging side by side.

But Kang and Liang had overplayed their hand. The pace of change was too swift; such radical moves as the abolishment of the eight-legged essay aroused strong opposition. It alarmed and alienated the old guard within the imperial court who were still loyal to the dowager empress in retirement at the Summer Palace. Persuaded by them that the emperor would move against her next, the dowager empress, who was not averse to some moderate reform, took it upon herself to squash her little nephew.

An unsuccessful pre-emptive coup against her, spearheaded by Tan Sitong, only expedited her moves. On 21 September 1898, 103 days after the first imperial decree, she announced that the emperor had been struck down by a serious illness (in fact he had been imprisoned on a small island in the imperial gardens) and that she was again taking over the administration of the empire. In addition to cancelling most of the reform edicts, she also issued orders for the arrest of Kang, Liang and Tan, among other reformist intellectuals. Kang had left Beijing a day earlier for Shanghai, from where he was able to escape to Hong Kong. Liang, who was still within the city walls, managed to find refuge in the Japanese legation. Tan joined him there, but only to say goodbye.

Liang pleaded with Tan to go with him to Japan, but Tan only said, in words to be commemorated by several Chinese generations, that China would never renew itself until men were prepared to die for it. He left the legation building and was immediately arrested. He and six other associates of Liang, including Kang’s younger brother, were sentenced to death. The declaration was read out from the gates of the Forbidden City. The condemned were taken in a cart to Caishikou market where many of the scholars visiting Beijing to take the civil service exams often stayed. A bowl of rice wine was offered to them outside a tea-house. A large crowd watched as the bowl was broken. The men were then made to kneel on the ground and were swiftly beheaded.

The graves of Kang Youwei’s family were desecrated on the orders of the dowager empress. As rewards for his own arrest and execution were announced, Liang fled, with Japanese help, to Tianjin, from where he sailed to a long and eventful exile in Japan. He was only twenty-five. Thus ended China’s opportunity to enact the kind of top-down modernization that Turkey and Egypt had attempted. Revolution became as inevitable as it had become in countries elsewhere in Asia.

Announcing a reward for Liang’s capture, the Peking Gazette referred to him as a ‘little animal with short legs, riding on the back of a wolf’.32 The image was meant to mock his intellectual dependence on Kang, but it was inaccurate. Liang, politically more pragmatic than his mentor, had already begun to move away from Kang.

Always hungry for knowledge – he had begun to study Japanese while still on board the ship that took him to Japan – he quickly started a newspaper, funded largely by Chinese merchants in Yokohama, and began to transmit new ideas as soon as he had absorbed them from Japanese books to an audience that now consisted of students as well as the scholar-gentry. Many of the students he had taught at Hunan moved to Japan to be with him. Liang put them up in his own living quarters until they were housed in a school he started in 1899 with the financial assistance of Chinese merchants.

In Japan, while Kang travelled to India and the West, Liang was to come into his own as China’s most famous intellectual, dealing, above all, with the problem of nationalism – given special urgency by his view of a world order defined by Social Darwinism. Writing in Japan in 1901, he bleakly concluded that

All men in the world must struggle to survive. In the struggle for survival, there are superior and inferior. If there are superior and inferior, then there must be success and failure. He who, being inferior, fails, must see his rights and privileges completely absorbed by the one who is superior and who triumphs. This, then, is the principle behind the extinction of nations.33

The Chinese intelligentsia were now divided between reformists like Kang and Liang and anti-Manchu revolutionaries represented by Sun Yat-sen. But Liang’s writings often transcended the differences, making them appealing to readers on a broad ideological spectrum in China. As Hu Shi, a liberal thinker and a bitter critic of Liang acknowledged (in a tone reminiscent of Mohammed Abduh’s tribute to al-Afghani): ‘He attracted our abundantly curious minds, pointed out an unknown world, and summoned us to make our own exploration.’ 34

Liang was helped a great deal by his setting. For educated Chinese, Japan was as much the centre of culture and education as Paris was for Westernized Russians and London for Indian colonials; thousands of Chinese students would travel there after 1900, and return to assume leadership positions at home. The Japanese had absorbed many Western ideas since the Meiji Restoration, and it was the first experience of modernity for many Chinese, such as Liang, forcing almost all of them to re-evaluate their previous notions about the world. Words like ‘democracy’, ‘revolution’, ‘capitalism’ and ‘communism’ were to make their way into the Chinese language via Japanese.

The Sinocentric worldview had been smashed to pieces by Western intrusions in China; and Liang would take it upon himself to describe harsh political realities that China had to come to terms with.

Because of our self-satisfaction and our inertia, the blindly cherished old ways have come down more than three thousand years to our day. Organization of the race, of the nation, of society, our customs, rites, arts and sciences, thought, morality, laws, religion, all are still, with no accretions, what they were three thousand years ago.35

This was an exaggeration, but made understandable by the scale of the challenges Liang felt himself confronted with. China was one of the oldest states in the world. But did its citizens see it as a nation? Could they shed their Confucian emphasis on self-cultivation enough to feel notions of civic solidarity? Indeed, could the state’s institutions be overhauled enough to cope with the challenges of international politics? And could a modern Chinese nation come into being without destroying China’s proud cultural identity? Liang posed these large

and complex questions without offering any clear-cut answers. Nevertheless, he phrased them more forcefully than all the other Chinese intellectuals. He had already sown the seeds of post-Qing China with his newspapers, schools and study-societies which radiated the urgency of change to the most secluded of Chinese scholar-gentry. His writings, smuggled back into the Chinese mainland from Japan, would now inspire the next generation of thinkers and activists.

However, first Liang had to negotiate his way through the tangled politics of both his Japanese hosts and the groups of Chinese expatriates in Japan. The Japan he travelled to in 1898 was still far from being the confident imperial power it would become after its defeat of Russia and annexation of Korea in 1910. Then it followed the precedent set by other imperialist powers in wanting its own share of the Chinese booty after war; in 1900, Japan was to participate in the Allied powers’ attempt to quell the Boxer Rising.

However, Japan feared the division of China in the same way that European powers dreaded the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire: the sick men of Asia were better alive than dead, for they held chaos at bay, and could also be bullied at will. Japanese statesmen closely followed the Hundred Days’ Reform, attracted by the prospect of a reformed Manchu ruling dynasty doing a better job of keeping China from total collapse. They appreciated the conservatism of Kang and Liang, who did not wish to depose the emperor. Ito Hirobumi, thrice prime minister of Japan and the main maker of the Meiji constitution, was in China when the dowager empress cracked down on the reformists; he quietly instructed Japanese diplomats to ensure the safety of Kang and Liang. When Kang Youwei reached Tokyo via Hong Kong in November 1898, he was treated as the head of a government-in-exile, and taken to meet the most powerful statesmen in Japan.

Kang and Liang received even greater support through unofficial channels. Despite an authoritarian political system, Japan possessed strikingly diverse intellectual currents. Its emergence as a major world power had brought it face to face with the racialist underpinnings of the international system – despite its successes, it was still regarded as a ‘yellow peril’ by Western powers, and in 1898 the United States had announced its presence in Japan’s neighbourhood by wresting the

Philippines from the doddering Spanish Empire (for the same reason Japan had removed Korea from the Chinese sphere of influence – because it was there to be taken).

Like any rising power, Japan was also developing an awareness of its ‘national interest’ that lay far beyond its physical borders. Tokutomi Soh summed it up: ‘The countries of the Far East falling prey to the great powers of Europe is something that our nation will not stand for … We have the duty to maintain peace in East Asia.’36 In 1885 Fukuzawa Yukichi had a responsive audience when he called for Japan to ‘escape’ Asia and join the West. But now the fear of a racially tinged Western imperialism pushed a wide range of Japanese intellectuals and politicians into fresh considerations of Japan’s cultural identity, and, by extension, its old links with China and the rest of Asia.

summed it up: ‘The countries of the Far East falling prey to the great powers of Europe is something that our nation will not stand for … We have the duty to maintain peace in East Asia.’36 In 1885 Fukuzawa Yukichi had a responsive audience when he called for Japan to ‘escape’ Asia and join the West. But now the fear of a racially tinged Western imperialism pushed a wide range of Japanese intellectuals and politicians into fresh considerations of Japan’s cultural identity, and, by extension, its old links with China and the rest of Asia.

This was the beginning of pan-Asianism, a major strand in Japan’s self-image and actions for the next half-century. For many Japanese the idea that Asian countries had grown weak, and exposed themselves to humiliation and exploitation by the West, was an undeniably solid basis for a pan-Asian identity; as was the demand for racial equality, which the Japanese were to struggle to enshrine as a principle in international relations. There was strength in numbers, and in the notion that Japan, being the first country to modernize itself, could force recognition of Asian dignity from Western powers. By virtue of its successful empowerment, Japan might even lead a crusade to free Asia from its European masters.

From the very beginning the advocates of pan-Asianism in Japan belonged to a broad ideological spectrum. Among them could be found, for instance, a figure such as Nagai Ry tar

tar (1881 – 1944), a devout Christian who championed many liberal causes such as universal suffrage and women’s rights, spoke admiringly of socialism and also sought to raise the alarm against what he called ‘the white peril’. ‘If one race assumes the right to appropriate all the wealth,’ he asked, ‘why should not all the other races feel ill-used and protest? If the yellow races are oppressed by the white races, and have to revolt to avoid congestion and maintain existence, whose fault is it but that of the oppressor?’37 Indeed, many of the self-appointed sentinels of Japan’s prestige saw themselves as guarding Asian values in general

against the ‘white peril’. According to Soh

(1881 – 1944), a devout Christian who championed many liberal causes such as universal suffrage and women’s rights, spoke admiringly of socialism and also sought to raise the alarm against what he called ‘the white peril’. ‘If one race assumes the right to appropriate all the wealth,’ he asked, ‘why should not all the other races feel ill-used and protest? If the yellow races are oppressed by the white races, and have to revolt to avoid congestion and maintain existence, whose fault is it but that of the oppressor?’37 Indeed, many of the self-appointed sentinels of Japan’s prestige saw themselves as guarding Asian values in general

against the ‘white peril’. According to Soh , Japan, rather than the West, was best placed to ‘create true universal equality and progress’.38 Some of these pan-Asianists were militarists who thought China and Korea ought to be ruled by Japan. Others were more sensitive to the interests of their neighbours, and hospitable to political refugees from China, Korea and South-east Asia. Liberal nationalists, who wished to modernize Japan in order to make it the equal of the West, felt obliged to strengthen China against foreign imperialists. More far-seeing and ambitious pan-Asianists saw Japan as the future imperial conqueror and leader of Asia. Their ranks would also include such idealists as Okuwa Shumei, Japan’s leading scholar of Indian and Islamic cultures, who was converted to pan-Asianism in 1913 after reading a book about India’s dire state under the British.

, Japan, rather than the West, was best placed to ‘create true universal equality and progress’.38 Some of these pan-Asianists were militarists who thought China and Korea ought to be ruled by Japan. Others were more sensitive to the interests of their neighbours, and hospitable to political refugees from China, Korea and South-east Asia. Liberal nationalists, who wished to modernize Japan in order to make it the equal of the West, felt obliged to strengthen China against foreign imperialists. More far-seeing and ambitious pan-Asianists saw Japan as the future imperial conqueror and leader of Asia. Their ranks would also include such idealists as Okuwa Shumei, Japan’s leading scholar of Indian and Islamic cultures, who was converted to pan-Asianism in 1913 after reading a book about India’s dire state under the British.

As Japan grew more powerful, there would develop a contradiction between its imperative to expand and dominate and the pan-Asianist desire to express solidarity with other Asian countries. Organizations such as the Kyujitai, the Amur River Society (popularly known as the Black Dragons) and the Genyosha (Great Ocean Society) would become increasingly militant and powerful advocates of Japan’s rights in Asia. But, initially at least, political differences among pan-Asianists did not matter much; many of the pan-Asianists, emerging at a time of transition, were looking for a new aim in life. The Meiji reforms had unleashed a whole class of political and intellectual adventurers, often former samurai, who saw themselves as nobly selfless idealists. These rootless men, who dreamed of saving China from itself, worked as pressure groups and lobbyists. They often attached themselves to the Chinese and South-east Asian nationalists who were beginning to arrive in Japan towards the end of the nineteenth century, and who had been forced into new ways of defining their identity and affirming their dignity by successive humiliations by the West – as members of nascent nations, races, classes, or such supra-national entities as pan-Islam and pan-Asia.

One such Japanese idealist was Miyazaki Toraz (1871 – 1922), a professional pan-Asianist and revolutionary, who tried to stir up an anti-Qing movement in China as early as 1891 and then later that decade smuggled guns to anti-American guerrillas in the Philippines. He decided he had found his saviour of China when he met Sun

Yat-sen in 1897. Thus Sun, who had already engineered a failed revolt in China, was installed in Japan, well-connected within the expatriate community of Chinese merchants and students, when Liang arrived there in the autumn of 1898, followed shortly afterwards by Kang Youwei. There were already many Chinese students in Yokohama, and the respective followers of these men soon began to join them in Japan. Their Japanese patrons tried to bring them together on a common platform of Chinese regeneration, encouraging them with money and advice to fuse their groups into a single party in exile. But they ran into the kind of internecine discord commonly found among nineteenth-century political expatriates, including the followers of Marx as well as of Herzen.

(1871 – 1922), a professional pan-Asianist and revolutionary, who tried to stir up an anti-Qing movement in China as early as 1891 and then later that decade smuggled guns to anti-American guerrillas in the Philippines. He decided he had found his saviour of China when he met Sun

Yat-sen in 1897. Thus Sun, who had already engineered a failed revolt in China, was installed in Japan, well-connected within the expatriate community of Chinese merchants and students, when Liang arrived there in the autumn of 1898, followed shortly afterwards by Kang Youwei. There were already many Chinese students in Yokohama, and the respective followers of these men soon began to join them in Japan. Their Japanese patrons tried to bring them together on a common platform of Chinese regeneration, encouraging them with money and advice to fuse their groups into a single party in exile. But they ran into the kind of internecine discord commonly found among nineteenth-century political expatriates, including the followers of Marx as well as of Herzen.

Unlike Kang and Liang, Sun came from a family of farmers in Guangzhou. Poverty forced his brother to emigrate; he went to Hawaii, and Sun joined him there in his early teens. Educated at missionary schools, Sun spoke English fluently and wrote classical Chinese badly. Dressed in Western-style clothes and financially beholden to overseas Chinese, Sun was as far away as possible from the traditional world of the Confucian gentry Kang and Liang belonged to. Well-travelled in the West, Sun also had a sharp eye for China’s infirmities. In 1894, when a bold petition from Sun to the imperial court was rejected, he was convinced that China needed to overthrow the Manchu monarchy and turn itself into a republic. This belief in itself would have caused problems with the royalist Kang. Nevertheless, Sun, a master improviser, was eager to join with Kang and Liang. As it turned out, Kang couldn’t abide Sun, regarding him as a worthless, boorish adventurer. Rebuffed, Sun, who was a convert to Christianity, came to regard Kang’s attempt to interpret Confucianism in the light of modern conditions as a meaningless academic exercise.

Kang’s uncompromising elitism also made him unpopular with the Japanese, who were already made nervous by Chinese protests over the presence of Sun, Liang and Kang in their country – the dowager empress had described them as China’s three greatest criminals. The pressures on Kang mounted, and in the summer of 1899 he left for Canada, where he formed, with the help of overseas Chinese, the ‘Society to Protect the Emperor’. Liang was left to deal with Sun and the former students who had flocked to his side from China.

The Japanese now tried to bring Sun and Liang together; and a degree of co-operation was established, especially over money. Liang was also more sympathetic to Sun’s anti-monarchy stance than he could freely express at the time. But just when the two seemed to be co-operating more closely in late 1899, Liang was ordered by Kang to travel to Hawaii and America on a fund-raising tour.

Liang complied; Kang was still his revered teacher in the Confucian tradition. But Japan had begun to emancipate him, as it was to do for two generations of Chinese thinkers. He had begun to read and think more widely. Dependent until then on Yan Fu’s translations, he expanded his knowledge of Hobbes, Spinoza, Rousseau and Greek philosophers, and even wrote biographical studies of Cromwell, Cavour and Mazzini. His knowledge of the world outside China broadened.

Qingyi Bao (‘Journal of Pure Critique’), the newspaper he started soon after arriving in Japan, carried reports on the Philippine resistance to the United States, and Britain’s difficulties with the Boers in South Africa. The modern competition for territory and resources began to preoccupy Liang above all, whether he was writing about the unification of Italy or the French subjugation of Vietnam. In Japan he also met many revolutionary thinkers and activists from India, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines; many of these had flocked to Japan after its defeat of Russia in 1905. Liang was in Japan in April 1907 when some Japanese socialists, Indians, Filipinos and Vietnamese formed the Asian Solidarity group in Tokyo, and he may not have disagreed much with another Chinese exile in Japan, Zhang Taiyan (1869 – 1936, also known as Zhang Binglin), the scholar of Buddhism, who, summing up the prevailing sentiments of cultural pride, political resentment and self-pity among Asian refugees, claimed in the society’s manifesto that

Asian countries … rarely invaded one another and treated each other respectfully with the Confucian virtue of benevolence. About 100 years ago, the Europeans moved east and Asia’s power diminished day by day. Not only was their political and military power totally lacking, but people also felt inferior. Their scholarship deteriorated and people only strove after material interests.39