Our old brother [India], ‘affectionate and missing’ for more than a thousand years is now coming to call on his little brother [China]. We, the two brothers, have both gone through so many miseries that our hair has gone grey and when we gaze at each other after drying our tears we still seem to be sleeping and dreaming. The sight of our old brother suddenly brings to our minds all the bitterness we have gone through for all these years.

Liang Qichao, welcoming Tagore to China in 1924

I read his [Tagore’s] essay on the Soviet Union in which he described himself as ‘I am an Indian under the British rule’; he knew himself well. Perhaps, if our poets and others had not made him a living fairy he would not have been so confused, and the [Chinese] youths would not have been so alienated. What bad luck now!

Lu Xun remembering Tagore’s visit in 1933

For many Chinese in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, India was the prototypical ‘lost’ country, one whose internal weakness, exploited by foreign invaders, had forced it into a state of subjugation that was morally and psychologically shameful, as well as politically and economically catastrophic. For ordinary Chinese, there were visible symbols of this Indian self-subjection in their own midst: Parsi businessmen from Bombay who acted as middlemen in the British opium trade with China; Indian soldiers who helped the British quell the Boxer Rising; and Sikh policemen in treaty ports like Shanghai, whom their British masters periodically unleashed on Chinese crowds. In 1904, a popular Tokyo-based Chinese journal Jiangsu published a short story describing a dreamlike journey into the future by a feckless Chinese literatus named Huang Shibiao (literally, ‘Representative of Yellow Elites’) and a mythical old man. Walking down the streets of Shanghai, they see a group of marching people led by a white man.

Shibiao looked closely at these people, and they all had faces black as coal. They were wearing a piece of red cloth around their heads like a tall hat; around their waists, they wore a belt holding wood clubs. Shibiao asked the old man: are these Indians? The old man said, yes, the English use them as police … Shibiao asked, why do they not use an Indian as the chief of police? The old man answered: who ever heard of that! Indians are people of a lost country; they are no more than slaves.1

Later in this dreamlike sequence, Shibiao sees a yellow-skinned man in a red Sikh-style turban; he turns out to be Chinese. The dream then quickly turns into a nightmare as Shibiao notices that everyone on the streets is wearing red turbans and that English is being taught in schools from textbooks designed by Christian missionaries. The story ends with Shibiao feeling profoundly disturbed by this vision of China subjected to India’s fate.

India, conquered and then mentally colonized, was also a cautionary tale for al-Afghani. But from the perspective of China, where despite its weaknesses a political-moral order based on Confucianism had endured, India seemed dangerously out of touch with its own cultural heritage. Indian philosophy and literature – which only Brahmans in possession of Sanskrit could read – had been a closed book to a

majority of Indians; it was the European discovery, and translation into English and German, of Indian texts that introduced a new Western-educated generation of Indian intellectuals to their cultural heritage.

As the Chinese saw it, foreigners had ruled the country continuously since the Mughals established their empire in the sixteenth century; there was no native ruling class capable of unifying the country. The most progressive elements seemed to be members of the Hindu castes that had faithfully served the imperial Muslim court and then turned into officials of the British as the latter expanded their administrative structures across the subcontinent.

Rabindranath Tagore’s family, connected to the British East India Company right from the settling of Calcutta in 1690, was a prominent beneficiary of the British economic and cultural reshaping of India. His grandfather was the first big local businessman of British India, and socialized with Queen Victoria and other notables on his trips to Europe; his elder brother was the first Indian to be admitted by the British into the Indian Civil Service (ICS).

Born in 1861, four years after the Indian Mutiny and the establishment of new Western-style universities in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay, Tagore was part of a new Indian intelligentsia – one that was exposed to a range of Western thought and was also influenced by the ‘social reform’ movements initiated by such men as Ram Mohun Roy (1774 – 1833), often called the ‘father of modern India’. Roy founded the Brahmo Sabha, a reformist society aimed at purging Hinduism of such evils as widow-burning and bringing it closer to a monotheistic religion like Christianity. Tagore’s father, Debendranath, adopted and then elaborated Roy’s syncretism in the organization Brahmo Samaj.

Just as many of China’s modern thinkers emerged from the regions near Canton and Shanghai, the parts of the country most exposed to the West, so the Bengalis of India’s eastern coast came to be natural leaders of what was later called the ‘Indian Renaissance’. Tagore himself grew up in a culturally confident and creative family, and was exposed early to European society and culture. This meant that he never partook of the strident anti-Westernism that began to overwhelm many of his Bengali compatriots in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Writing as late as 1921, when the tide of Indian nationalism was rising fast, he protested that ‘if, in the spirit of national vainglory, we shout from our house-tops that the West has produced nothing that has an infinite value for man, then we only create a serious cause of doubt about the worth of any product in the Eastern mind.’2 He would later develop serious differences with Gandhi over what he saw as the xenophobic aspect of the anti-colonial movement. At the same time, Tagore could never be part of ‘Young Bengal’, a group of Western-educated Bengalis who sought to escape Asia and join Europe just as fervently as the Ottoman Tanzimatists and the Meiji intellectuals in Japan had. Committed to a larger vision of the divine in man, and the essential unity of mankind, Tagore became in fact one of the clearest observers and strongest critics of India’s Europeanization.

In nineteenth-century India, movements dedicated to reforming Hinduism and restoring its lost glory had grown very rapidly, part of the same larger trend mentioned previously of religious-political assertion in Muslim, Buddhist and Confucian societies. The inspiration and rhetoric of these neo-Hindu movements might have seemed archaic but, though often born out of a sense of racial humiliation, they were largely inspired by the ideas of progress and development that British Utilitarians and Christian missionaries aggressively promoted in India. The social reformer Dayananda Saraswati (1824 – 83), for instance, exhorted Indians to return to the Vedas, which contained, according to him, all of modern science; and echoed British missionary denunciations of such ‘Hindu superstitions’ as idol-worship and the caste system.

This ‘modernization’ of Indian religion under semi-European auspices was to release new political and social movements across India, many of them militantly opposed to British rule and dedicated to recovering national dignity. One emblematic figure of this ambiguous Europeanization of Indian culture was Bankim Chandra Chatterji (1838 – 94), an official in the British government in Bengal, who moved in his lifetime from Young Bengal-style uncritical adoration of the West to being the first icon of Hindu nationalism.

Bengalis were ‘drunk with the wine of European civilization’, Aurobindo Ghose complained in 1908, no doubt thinking of his own

upbringing in a fanatically Anglophile Bengali family.3 Saddled with the middle name ‘Ackroyd’, and banished to English public schools in the 1880s, Aurobindo acquired his knowledge of Indian languages and literature from European Orientalist scholars, and returned home in the early 1890s a bitter critic of the British and their Bengali imitators. As he saw it, ‘the movements of the nineteenth century in India were European movements’ which

adopted the machinery and motives of Europe, the appeal to the rights of humanity or the equality of social status and an impossible dead level which Nature has always refused to allow. Mingled with these false gospels was a strain of hatred and bitterness, which showed itself in the condemnation of Brahminical priestcraft, the hostility to Hinduism and the ignorant breaking away from the hallowed traditions of the past.4

Such was the Bengali infatuation with Europe, Aurobindo claimed, that India as a whole ‘was in danger of losing its soul by an insensate surrender to the aberrations of European materialism’. But it was also Bengalis who in the second half of the nineteenth century articulated an overwhelmingly negative view of the materialistic West, even as they grudgingly admired and sought to emulate some of its practical skills. For Swami Vivekananda (1863 – 1902), the earliest and most famous of Indian spiritual leaders, Europeans were the children of Virochana, the great demon of Indian mythology, who believed that the human self was nothing but the material body and its grosser cravings. ‘For this civilization,’ Vivekananda wrote of the West, ‘the sword was the means [for the attainment of given ends], heroism the aid, and enjoyment of life in this world and the next the only end.’5

Vivekananda, who visited Europe and America often in his short life, saw Western societies and politics as controlled by the rich and powerful, and quite akin in their class stratifications to the Indian caste system: ‘Your rich people are Brahmans,’ he told his English friends on his last visit to Britain, ‘and your poor people are Sudras.’6 For Bhudev Mukhopadhyay, perhaps the most comprehensive nineteenth-century Bengali critic of the West, the innate human capacity for love had stopped, in Europe, at the door of the nation-state – it was the end-point of Europe’s history and its endless conflicts. This faculty of love had latched on to such strange objects as money and

an excessive concern for property rights – an extreme individualism that relieved human beings of their usual obligations to society and combined with machinery and the quest for markets and monopolies to lead to endless wars and conquests and violence. What was most galling for Mukhopadhyay was that the European never seemed to experience any contradiction between his selfish needs and the demands of morality. ‘Whatever is to their interest,’ Mukhopadhyay wrote about Europeans, ‘they find consistent with their sense of what is right at all times, failing to understand how their happiness cannot be the source of universal bliss.’7

Aurobindo Ghose, too, raged against the English middle class that, unlike previous ruling classes, cloaked their imperialism in noble proclamations and intentions. England, he claimed, had conquered Ireland using the old methods of ‘cynical treachery’ and ‘ruthless massacre’ and then ruled it with the principle ‘might is right’. But in the age of democratic nationalism, imperialism needed deeper self-justifications:

The idea that despotism of any kind was an offence against humanity, had crystallised into an instinctive feeling, and modern morality and sentiment revolted against the enslavement of nation by nation, of class by class or of man by man. Imperialism had to justify itself to this modern sentiment and could only do so by pretending to be a trustee of liberty, commissioned from on high to civilise the uncivilised and train the untrained until the time had come when the benevolent conqueror had done his work and could unselfishly retire. Such were the professions with which England justified her usurpation of the heritage of the Moghul and dazzled us into acquiescence in servitude by the splendour of her uprightness and generosity. Such was the pretence with which she veiled her annexation of Egypt. These Pharisaic pretensions were especially necessary to British Imperialism because in England the Puritanic middle class had risen to power and imparted to the English temperament a sanctimonious self-righteousness which refused to indulge in injustice and selfish spoliation except under a cloak of virtue, benevolence and unselfish altruism.8

For Aurobindo, Indians who believed European claims to such superior values as democracy and liberalism were deluding themselves.

For the British themselves considered such ideals ‘unsuitable to a subject nation where the despotic supremacy of the white man has to be maintained, as it was gained, at the cost of all principles and all morality’. Infused with a fierce new pride in India by his Oriental education, Aurobindo steadily turned into a militant nationalist, convinced that ‘there can be no European respect for Asiatics, no sympathy between them except the “sympathy” of the master for the slave, no peace except that which is won and maintained by the Asiatic sword’.9

Like Aurobindo, Tagore was greatly influenced by the Orientalist scholarship that endowed India with a classical past. And he absorbed some of the Bengali suspicion of the modern West. In 1881, early in his career, he proclaimed his political distance from his businessman grandfather, a crucial intermediary in the opium trade. But his own intellectual and spiritual journey from a conservative aristocratic background and Western-style education took him to a very different place from that of his Bengali compatriots.

His long sojourn in the Bengali countryside between 1891 and 1901 was crucial in this regard. Proximity to lives in Indian villages helped distinguish his worldview from that of the middle-class intellectuals in Calcutta. It unleashed a love of natural landscapes, a regard for the everyday, the domestic and the fragmentary, as well as an insight into the plight of the rural poor. He remained convinced for the rest of his life of the moral superiority of pre-industrial civilization over the mechanized modern one; he became certain, too, that India’s self-regeneration had to begin in its villages.

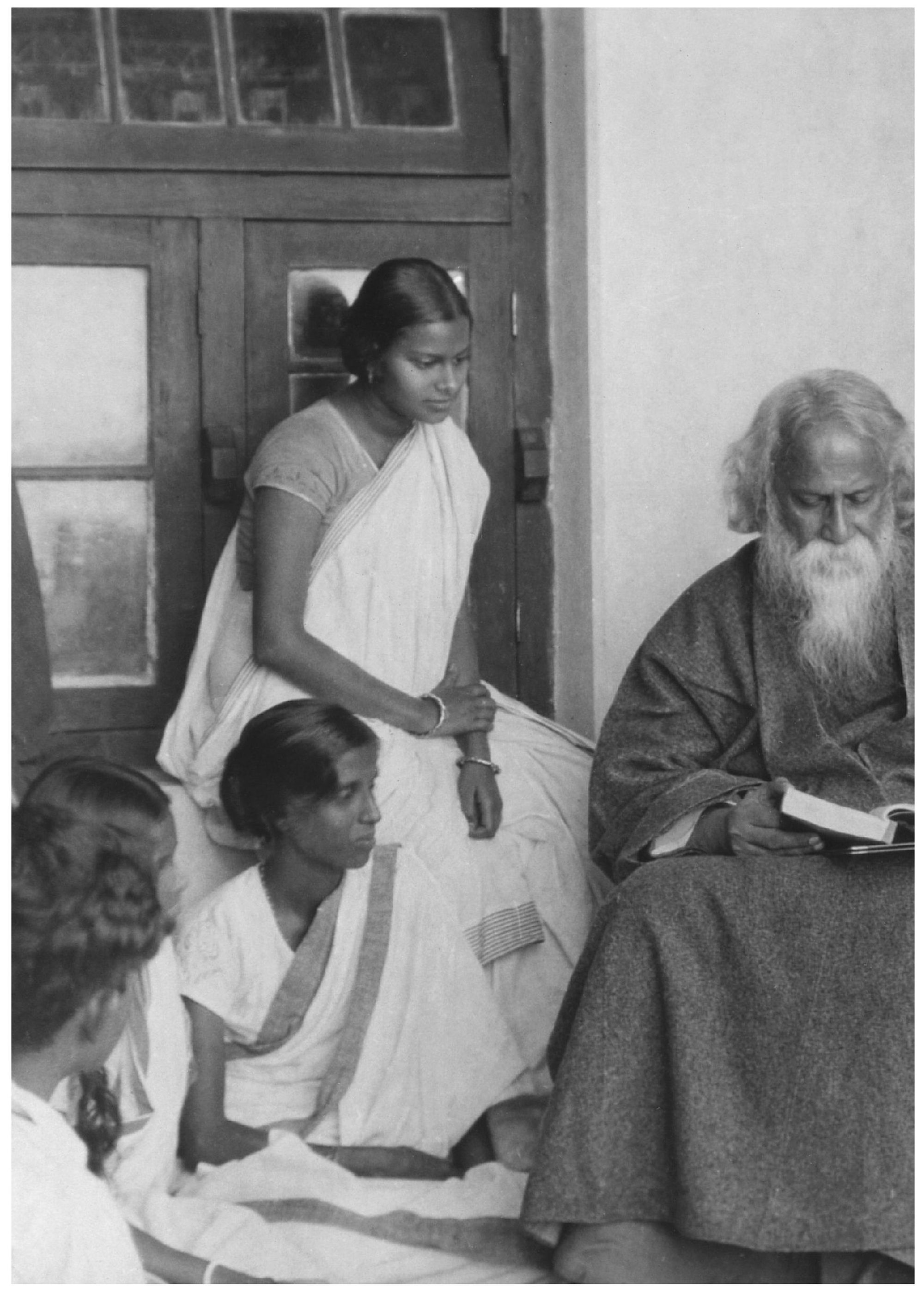

In 1901, he founded an experimental school in rural south-western Bengal. Santiniketan, as it was called, would expand into an international university, and train some of India’s leading artists and thinkers (including the filmmaker Satyajit Ray and the economist Amartya Sen). That same year, in an essay titled ‘Eastern and Western Civilization’, Tagore first developed his thesis of a dichotomy between rural harmony and urban aggressiveness, village-centred society and the nation-state. The East prescribed modes of social harmony and spiritual liberation. On the other hand, the West, he argued, was dedicated to strengthening national sovereignty and political freedom. ‘Scientific rather than human’, it was

overrunning the whole world, like some prolific weed … It is carnivorous and cannibalistic in its tendencies, it feeds upon the resources of other peoples and tries to swallow their whole future … It is powerful because it concentrates all its forces upon one purpose, like a millionaire acquiring money at the cost of his soul.10

The imperialist wars in South Africa and the suppression of the Boxer Rising, both involving Indian soldiers, had confirmed Tagore’s scepticism. On 31 December 1900, he completed a poem titled ‘Sunset of the Century’: ‘The century’s sun has set in blooded clouds. / There rings in the carnival of violence / from weapon to weapon, the mad music of death.’11 Tagore concluded the poem by scorning such imperialist poets as Rudyard Kipling, who had exhorted America to take up the white man’s burden in the Philippines: ‘Awakening fear, the poet-mobs howl round / A chant of quarrelling curs on the burning-ground.’

From 1905 to 1908 Tagore was very attracted to the Swadeshi Movement, led by young Bengali firebrands who boycotted British goods and aimed at economic self-sufficiency. It was after the widespread protests against Lord Curzon’s partition of Bengal in 1905 that he composed the two songs that subsequently became the national anthems of India and Bangladesh. Like most Asian intellectuals, Tagore rejoiced in Japan’s victory over Russia in 1905, taking his pupils at Santiniketan on an impromptu victory parade. But already in 1902, three years before that landmark event in the political awakening of Asia, he was hoping it would steer clear of mindless imitation of the West:

The harder turns our conflict with the foreigner, the greater grows our eagerness to understand and attain ourselves. We can see that this is not our case alone. The conflict with Europe is waking up all civilized Asia. Asia today is set to realizing herself consciously, and thence with vigour. She has understood, know thyself – that is the road to freedom. In imitating others is destruction.12

Tagore saw no reason for Asians to believe that the ‘building up of a nation on the European pattern is the only type of civilization and the only goal of man’.13 After a brief fascination with the Swadeshi militants, he recoiled from the militant Indian nationalism inspired by thinkers like Chatterji, especially the series of assassinations and

terrorist attacks by young Bengali nationalists in the first decade of the twentieth century. He explored the middle-class fascination with violent politics in such novels as Gora (1910) and Ghare Baire (‘Home and the World’, 1916). But from 1917 he conducted a systematic critique of nationalism in his essays and speeches. The nation-state, he told audiences in America that year, ‘is a machinery of commerce and politics turn[ing] out neatly compressed bales of humanity’.14 ‘When this idea of the Nation, which has met with universal acceptance in the present day, tries to pass off the cult of selfishness as a moral duty … it not only commits depredations but attacks the very vitals of humanity.’15 Like Kang Youwei, he formulated a non-nationalist ideal of Asian cosmopolitanism early in his life, and never departed from it. ‘India has never had a real sense of nationalism … it is my conviction that my countrymen will truly gain their India by fighting against the education which teaches that a country is greater than the ideals of humanity.’16

Tagore wasn’t the only Indian with serious apprehensions about the trajectory of modern European civilization and its over-eager followers in the East. Travelling from London to South Africa in November 1909, the forty-year-old Gandhi feverishly wrote, in nine days, a stirring anti-modern manifesto titled Hind Swaraj that summed up many prevailing intellectual arguments against the West, and also anticipated many others still to come. Like Tagore, with whom he had a long and mutually enriching friendship, Gandhi in 1909 was engaged in a polemical battle with his radical and revolutionary peers who saw salvation in the wholesale imitation of Western-style state and society. Many of these were Hindu nationalists, the ideological children of Bankim Chandra Chatterji and later part of a religious-cultural movement that derived inspiration from the Fascist parties of Italy and Germany, and which aimed to unite India through a monolithic Hindu nationalism derived from the joint British-Indian reinvention of Hinduism in the nineteenth century. Gandhi saw that these nationalists would merely replace one set of deluded rulers in India with another: ‘English rule’, he wrote in Hind Swaraj, ‘without the Englishman.’

Gandhi’s own ideas were rooted in a wide experience of a freshly globalized world. Born in 1869 in a backwater Indian town, he came

of age on a continent pathetically subject to the West, intellectually as well as materially. Dignity, even survival, for many uprooted Asians seemed to lie in careful imitation of their Western conquerors. Gandhi, brought out of his semi-rural setting and given a Western-style education, initially attempted to become more English than the English. He studied law in London and, on his return to India in 1891, tried to set up first as a lawyer, then as a schoolteacher. But a series of racial humiliations during the following decade awakened him to his real position in the world.

Moving to South Africa in 1893 to work for an Indian trading firm, he was exposed to the dramatic transformation wrought by the tools of Western modernity: printing presses, steamships, railways and machine guns. In Africa and Asia, a large part of the world’s population was being incorporated into, and made subject to the demands of, the international capitalist economy. Gandhi keenly registered the moral and psychological effects of this worldwide destruction of old ways and lives and the ascendancy of Western cultural, political and economic norms.

As Gandhi wrote later in Satyagraha in South Africa, ‘the nations which do not increase their material wants are doomed to destruction. It is in pursuance of these principles that western nations have settled in South Africa and subdued the numerically overwhelmingly superior races of Africa.’17 Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg implicated capitalism in imperialism; and Gandhi, too, believed that colonial economic policies, enabled by native Indians, were meant to benefit foreign investors, and actually impoverished the mass of India’s population. But he went further, implicating the whole of modern civilization and its obsession with economic growth and political sovereignty (the latter inevitably achieved through violence).

Gandhi eagerly acknowledged the many benefits of Western modernity, such as civil liberties, the liberation of women and the rule of law. Yet he saw these as inadequate without a broader conception of spiritual freedom and social harmony. He was of course not alone. By the early twentieth century, modern Chinese and Muslim intellectuals like al-Afghani and Liang Qichao were also turning away from Europe’s universalist ideals of the Enlightenment – which they saw as a moral cover for unjust racial hierarchies – to seek strength and dignity

in a revamped Islam and Confucianism. The same year that Gandhi wrote Hind Swaraj, Aurobindo Ghose sardonically wondered:

Is this then the end of the long march of human civilisation, his spiritual suicide, this quiet petrifaction of the soul into matter? Was the successful business-man that grand culmination of manhood toward which evolution was striving? After all, if the scientific view is correct, why not? An evolution that started with the protoplasm and flowered in the orang-utan and the chimpanzee, may well rest satisfied with having created hat, coat and trousers, the British Aristocrat, the American capitalist and the Parisian Apache. For these, I believe, are the chief triumphs of the European enlightenment to which we bow our heads.18

However, the terms of Gandhi’s critique, as set out in Hind Swaraj, were remarkably original. He claimed that modern civilization had introduced a whole new and deeply ominous conception of life, overturning all previous notions of politics, religion, ethics, science and economics. According to him, the Industrial Revolution, by turning human labour into a source of power, profit and capital, had made economic prosperity the central goal of politics, enthroning machinery over men and relegating religion and ethics to irrelevance. As Gandhi saw it, Western political philosophy obediently validated the world of industrial capitalism. If liberalism vindicated the preoccupation with economic growth at home, liberal imperialism abroad made British rule over India appear beneficial for Indians – a view many Indians themselves subscribed to. Europeans who saw civilization as their unique possession denigrated the traditional virtues of Indians – simplicity, patience, otherworldliness – as backwardness.

Gandhi never ceased trying to overturn these prejudices of Western modernity. Early in his political career, he began wearing the minimal garb of an Indian peasant and rejected all outward signs of being a modern intellectual or politician. True civilization, he insisted, was about moral self-knowledge and spiritual strength rather than bodily well-being, material comforts, or great art and architecture. He upheld the self-sufficient rural community over the heavily armed and centralized nation-state, cottage industries over big factories, and manual labour over machines. He also encouraged his political activists, satyagrahis, to feel empathy for their political opponents and to abjure violence against

the British. For, whatever their claims to civilization, the British, too, were victims of the immemorial forces of human greed and violence that had received an unprecedented moral sanction in the political, scientific and economic systems of the modern world. Satyagraha might awaken in them, too, an awareness of the profound evil of industrial civilization.

Like Tagore, Gandhi opposed violence and rejected nationalism and its embodiment, the bureaucratic, institutionalized, militarized state – it was what in 1948 angered and provoked his assassin, a Hindu nationalist agitating for an aggressively armed, independent India. Both made national regeneration incumbent upon individual regeneration. Until it was cut short by Tagore’s death in 1941, the two pursued a rich conversation covering their disagreements as well as shared preoccupations. But in 1909 when he wrote Hind Swaraj, Gandhi was still an unknown figure outside South Africa; his book did not attract attention until a decade later. Tagore was by far the more famous and influential Indian.

Soon after receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, Tagore had become an international literary celebrity and spokesperson for the East. This was a unique privilege for him in many ways in a world where few, if any, voices from Asia were heard. As Lu Xun pointed out in 1927, ‘Let us see which are the mute nations. Can we hear the voice of Egypt? Can we hear the voice of Annam and Korea? Except Tagore what other voice of India can we hear?’19 Tagore’s long white beard and intense gaze made him appear like some kind of prophet from the East. Receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1968, the Japanese novelist Yasunari Kawabata recalled

the features and appearance of this sage-like poet, with his long bushy hair, long moustache and beard, standing tall in loose-flowing Indian garments, and with deep, piercing eyes. His white hair flowed softly down both sides of his forehead; the tufts of hair under the temples also were like two beards and linking up with the hair on his cheeks, continued into his beard, so that he gave an impression, to the boy that I was then, of some ancient Oriental wizard.20

Packed lecture-halls awaited Tagore around the world, from Japan to Argentina. President Herbert Hoover received him at the White

House when he visited the United States in 1930, and the New York Times ran twenty-one reports on the Indian poet, including two interviews. This enthusiasm seems especially remarkable given the sort of prophecy from the East that Tagore would deliver to his Western hosts: that their modern civilization, built upon the cult of money and power, was inherently destructive and needed to be tempered by the spiritual wisdom of the East. But when, travelling in the East, he expressed his doubts about Western civilization and exhorted Asians not to abandon their traditional culture, he ran into fierce opposition.

By 1916 when he first arrived in Japan, Tagore had long been an admirer of the country. Japan’s victory over Russia in 1905 had prompted him to write a verse contrasting the transmission of Buddhism from India to Japan with the need to learn new techniques from the Japanese:

Wearing saffron robes, the Masters of religion [dharma]

Went to your country to teach.

Today we come to your door as disciples,

To learn the teachings of action [karma].21

Went to your country to teach.

Today we come to your door as disciples,

To learn the teachings of action [karma].21

On his first visit, Tagore seemed assured of an audience for his advocacy of inter-Asian co-operation. Many important Japanese nationalists had dabbled in pan-Asianism. Kakuzo Okakura (1862 – 1913), one of Japan’s leading nationalist intellectuals, was already known to Tagore. He had begun his 1903 book, The Ideals of the East, with the resonant declaration that ‘Asia is one. The Himalayas divide, only to accentuate, two mighty civilizations, the Chinese with its communism of Confucius, and the Indian with its individualism of the Vedas.’ Okakura claimed that, ‘Arab chivalry, Persian poetry, Chinese ethics and Indian thought, all speak of a single Asiatic peace, in which there grew up a common life, bearing in different regions different characteristic blossoms, but nowhere capable of a hard and fast dividing line.’22

Okakura had been alerted to Japan’s cultural heritage by his American teacher Ernest Fenollosa, an art historian and philosopher who believed that it was Asia’s destiny to spiritualize the modern West. Just

as Western Oriental scholarship about India informed Tagore’s views of Asia and the West, so did Fenollosa’s Japanophilia suffuse Okakura’s idealized notion of Asian unity. He had spent a year in India in 1901 – 2, staying for some of this time in the Tagore family’s mansion in Calcutta, where he drafted The Ideals of the East and influenced a host of Indian artists. Tagore subsequently received a stream of Japanese visitors sent by Okakura at his rural retreat in Santiniketan; and Okakura himself revisited India in 1911 on his way to Boston, where he was now a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts. Okakura was to become a major influence on such varied figures as Frank Lloyd Wright, T. S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, Ezra Pound and even Martin Heidegger. In Tagore, however, he found a fellow traveller, someone also prone to uphold Asia’s oneness and investigate the moral claims of the West. ‘The guilty conscience of the West’, Okakura wrote, ‘has often conjured up the spectre of a Yellow Peril, let the tranquil gaze of the East turn itself on the White Disaster.’23 Tagore concurred, at least partly. Like Gandhi, both men proclaimed their Asianness by partly rejecting Western dress. Okakura dressed in a dhoti while visiting the Ajanta caves in India; Tagore was to wear a Taoist hat in China. Both writers also sought to establish a cultural basis for Asia as a whole, stressing old maritime links, arts, and such shared legacies as Buddhism in India, China and Japan.

Advocating the essential oneness of humanity, Tagore once compared the two journeys of Buddhism and opium to the East:

When the Lord Buddha realised humanity in a grand synthesis of unity, his message went forth to China as a draught from the fountain of immortality. But when the modern empire-seeking merchant, moved by his greed, refused allegiance to this truth of unity, he had no qualms in sending to China the deadly opium poison.24

Again and again in his writings, Tagore returned to the metaphor of modern civilization as a machine: ‘The sole fulfillment of a machine is in achievement of result, which in its pursuit of success despises moral compunctions as foolishly out of place.’25 Japan, Tagore wrote, could further the ‘experiments … by which the East will change the aspects of modern civilization, infusing life in it where it is a machine, substituting the human heart for cold expediency’.

A more militant kind of Indian had made Japan his home before Tagore’s arrival in 1916. These Indians were part of the foreign communities that had flocked to Japan to learn the secrets of its modernization. Along with New York and London, Tokyo was part of an international network of ‘India Houses’, where activists and self-styled revolutionaries exiled from India gathered. An Indian Muslim, Maulavi Barkatullah (1854 – 1927), edited a magazine titled The Indian Sociologist from Tokyo. In 1910 he revived The Islamic Fraternity, the English monthly that Abdurreshid Ibrahim had set up, and which the Japanese, yielding to British requests, had closed down. Barkatullah turned it into an explicitly anti-British forum. He also wrote for the influential Japanese pan-Asianist thinker Okawa Shumei, who had begun to outline a Japanese version of the Monroe Doctrine for Asia (in 1946 he would be indicted by the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal as the main civilian ideologue of Japanese expansionism).

The revolutionary strain of Bengali nationalism was also well represented in Japan by Rash Behari Bose (1886 – 1945), another Indian associate of Okawa Shumei. At the age of twenty-six, he threw a hand grenade at the then British viceroy as the latter ceremonially entered Delhi on the back of an elephant. He missed. Escaping India, he ended up in Japan in 1915, where he lived buoyed by the pan-Asianist sentiment and the financial assistance of many members of the Japanese elite until his death from natural causes in January 1945. When the hero of Indian revolutionaries, Lala Lajpat Rai, visited Japan in November 1915, Okawa and Bose organized a reception for him. Speaking on the occasion, Rai exhorted his hosts to work for the liberation of Asia. British pressure led to deportation orders being issued for Bose the next day, but the Indian nationalists and Okawa then successfully lobbied Toyama Mitsuru, the most influential of the pan-Asianists, to intervene on Bose’s behalf.  kawa would write his first book on Indian nationalism after Tagore’s visit to Japan, selectively quoting the latter to support his contention that it was Japan’s ‘mission to unite and lead Asia’. In 1917, he would also encourage the Bengali revolutionary Taraknath Das to write a book claiming that conflict between the white and yellow races was inevitable.

kawa would write his first book on Indian nationalism after Tagore’s visit to Japan, selectively quoting the latter to support his contention that it was Japan’s ‘mission to unite and lead Asia’. In 1917, he would also encourage the Bengali revolutionary Taraknath Das to write a book claiming that conflict between the white and yellow races was inevitable.

But Tagore, like Gandhi, had little time for militant nationalists,

and he was alarmed in 1916 to see a country that was then in the midst of an extraordinary growth of national self-confidence and imperialist expansion, and preparing, too, for more battles ahead with both old enemies and new friends. The previous year, 1915, Japan had annexed Chinese territories in Shandong. In 1905 Japan had declared Korea a protectorate, and in 1910 had forced it to surrender its sovereignty. The United States had supported Japan’s move then; Theodore Roosevelt was reported to have said, ‘I should like to see Japan have Korea.’26 But relations between Japan and the United States had been deteriorating since the 1890s, over the latter’s big move into the Pacific and its occupation of Hawaii. And American treatment of Japanese immigrants enraged nationalist Japanese like Tokutomi Soh .

.

Soh also worried that the First World War, which he saw as an internecine struggle between Western European powers for global dominance, would bring trouble to Japan’s neighbourhood, no matter who won. Japan had to move first in East Asia to forestall European and American influence there, he wrote, echoing Okuwa Shumei’s Asian Monroe Doctrine. Those pan-Asianists who were also ultra-nationalists were beginning to dream of an Asia liberated from its European masters and revitalized by Japan, and they saw Tagore as a likely collaborator in a pro-Japan freedom movement across Asia.

also worried that the First World War, which he saw as an internecine struggle between Western European powers for global dominance, would bring trouble to Japan’s neighbourhood, no matter who won. Japan had to move first in East Asia to forestall European and American influence there, he wrote, echoing Okuwa Shumei’s Asian Monroe Doctrine. Those pan-Asianists who were also ultra-nationalists were beginning to dream of an Asia liberated from its European masters and revitalized by Japan, and they saw Tagore as a likely collaborator in a pro-Japan freedom movement across Asia.

But Tagore was set to disappoint. He had developed some doubts about Japan’s progress well before he left India. ‘I am almost sure that Japan has her eyes on India,’ he wrote to an English friend in June 1915. ‘She is hungry – she is munching Korea, she has fastened her teeth upon China and it will be an evil day for India when Japan will have her opportunity.’27 His mood soured throughout the long journey that took him, tracing the route of his opium-trading grandfather, via Rangoon, Penang and Singapore. The polluting chimneys and lights and noise of these port cities made him inveigh against the ‘trade monster’ which ‘lacerates the world with its greed’.28 In Hong Kong, he was appalled to see a Sikh beating up a Chinese worker.

Watching Chinese labourers diligently at work in the port city, he made a canny prophecy about the future balance of power in international relations: ‘The nations which now own the world’s resources fear the rise of China, and wish to postpone the day of that rise.’29 But

Tagore seemed to derive no comfort from the prospect of any country rising in the manner prescribed by the modern West. ‘The New Japan is only an imitation of the West,’ he declared at his official reception in Tokyo, which included the Japanese prime minister among other dignitaries. This did not go down well with his audience, for whom Japan was a powerful nation and budding empire, and India a pitiable European colony.

Tagore had received most of his impressions of the country from Okakura, but Japan had changed rapidly in the period between 1900 and 1916. In such books as The Awakening of Japan (1904) and The Book of Tea (1906), Okakura himself had begun to advocate a more assertive Japanese identity. ‘When will the West understand, or try to understand, the East?’ he had asked exasperatedly in The Book of Tea:

We Asiatics are often appalled by the curious web of facts and fancies which has been woven concerning us. We are pictured as living on the perfume of the lotus, if not on mice and cockroaches. It is either impotent fanaticism or else abject voluptuousness. Indian spirituality has been derided as ignorance, Chinese sobriety as stupidity, Japanese patriotism as the result of fatalism. It has been said that we are less sensible to pain and wounds on account of the callousness of our nervous organization!30

Tagore agreed with Okakura on most counts. Nevertheless, the vogue for patriotism depressed him. Writing his lectures on nationalism in the West, which he planned to deliver in the United States, Tagore concluded:

I have seen in Japan the voluntary submission of the whole people to the trimming of their minds and clipping of their freedoms by their governments … The people accept this all-pervading mental slavery with cheerfulness and pride because of their nervous desire to turn themselves into a machine of power, called the Nation, and emulate other machines in their collective worldliness.31

In a long letter home, Tagore mentioned caustically how the Japanese who dismissed his exhortations as the ‘poetry of a defeated people’ were ‘right’: ‘Japan had been taught in a modern school the lesson of

how to become powerful. The schooling is done and she must enjoy the fruits of her lessons.’32

In China in 1924, torn apart by civil war and ravaged by warlords, Tagore’s invoking of Asia’s spiritual traditions was never likely to go down well. The May Fourth Movement had expanded since 1919. Returning from their studies in Berlin, Paris, London, New York and Moscow, young men introduced and discussed a range of ideas and theories. By general consensus, they rejected their country’s Confucian traditions. As Chen Duxiu wrote, ‘I would much rather see the past culture of our nation disappear than see our race die out now because of its unfitness for living in the world.’33

For the May Fourth generation, the egalitarian ideals of the French and Russian revolutions and the scientific spirit underlying Western industrial power were self-evidently superior to an ossified Chinese culture that exalted tradition over innovation and kept China backward and weak. They wished China to become a strong and assertive nation using Western methods, and they admired such visitors as Bertrand Russell and John Dewey, whose belief in science and democracy seemed to lead the way to China’s redemption. In 1924, few of them were ready to listen to an apparently otherworldly poet from India hold forth on the problems of modern Western civilization and the virtues of old Asia.

In 1923, a debate erupted among Chinese intellectuals as soon as Tagore’s visit was announced. Radicals such as the novelist Mao Dun, who had once translated Tagore, worried about his likely deleterious effect on Chinese youth. ‘We are determined’, he wrote, ‘not to welcome the Tagore who loudly sings the praises of eastern civilization. Oppressed as we are by militarists from within the country and by the imperialists from without, this is no time for dreaming.’34 Tagore’s host, Liang Qichao, was already under attack from young radicals, who also kept up a barrage of insults against the romantic poet Xu Zhimo, Tagore’s interpreter in China.

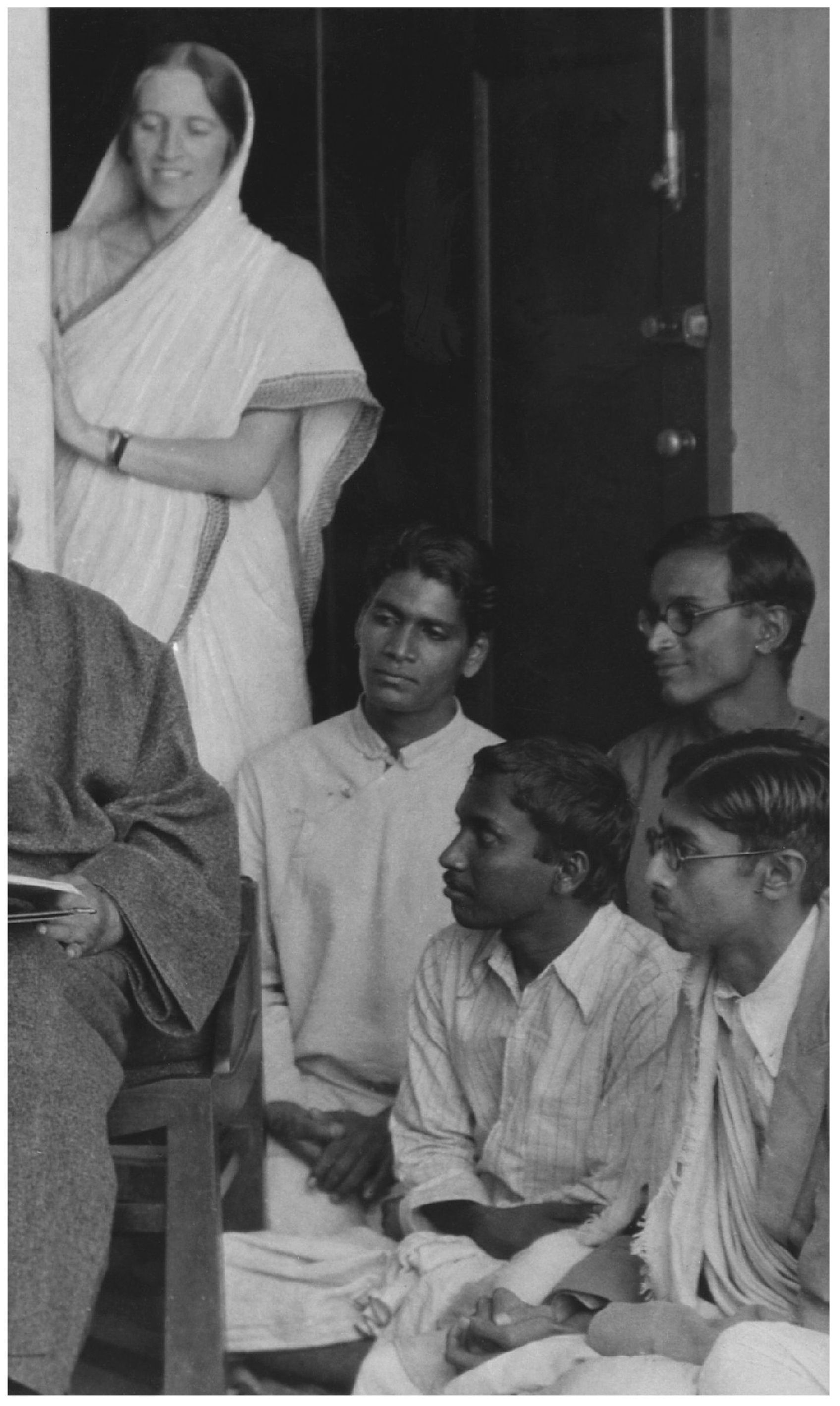

In Shanghai and Hangzhou Tagore spoke to large gatherings of students. As always he cut an impressive figure in his robes and long white beard. He attended garden parties and music concerts, often accompanied by Liang Qichao and Zhang Junmai. In Nanjing he met

the reigning warlord and pleaded with him to cease fighting. The warlord served champagne to his guests, and assured Tagore he was fully in agreement with his message of peace. (A few months later, he launched an assault on the warlord of Zhejiang.)

Lecturing in Beijing, Tagore returned to his favourite theme:

The West is becoming demoralized through being the exploiter, through tasting of the fruits of exploitation. We must fight with our faith in the moral and spiritual power of men. We of the East have never reverenced death-dealing generals, nor lie-dealing diplomats, but spiritual leaders. Through them we shall be saved, or not at all. Physical power is not the strongest in the end … You are the most long lived race, because you have had centuries of wisdom nourished by your faith in goodness, not in mere strength.35

The Chinese radicals grew alarmed as Tagore praised Buddhism and Confucianism for nurturing a civilization ‘in its social life upon faith in the soul’. The Communist Party and Chen Duxiu had already decided to campaign against Tagore through its various magazines. Chen worried that Chinese youth were vulnerable to Tagore’s influence: ‘We warn them not to let themselves be Indianized. Unless, that is, they want their coffins to lie one day in a land under the heel of a colonial power, as India is.’36

The propaganda campaign seems to have worked. At one meeting in Hankou, Tagore had been greeted with the slogans, ‘Go back, slave from a lost country! We don’t want philosophy, we want materialism!’ The vociferous hecklers had to be physically restrained lest they assaulted him. But it was in Beijing, the centre of youthful Chinese radicalism, that Tagore faced organized hostility in the form of primed questioners and boos and heckles. At one of his meetings, where he attacked modern democracy itself, which he claimed benefited ‘only plutocrats in various disguises’, leaflets denouncing him were handed out.37 ‘We have had enough of the ancient Chinese civilization.’ They went on to attack Tagore’s hosts, Liang Qichao and Zhang Junmai, who used ‘his talent to instill in Young China their conservative and reactionary tendencies’.38 The communist poet Qu Quibai summed up the general tone of Tagore’s reception in China when he wrote,

‘Thank you, Mr. Tagore, but we have already had too many Confuciuses and Menciuses in China.’39

In retrospect, Tagore, angrily recoiling from the main intellectual and political trends in Japan and China, seems to have misunderstood their context. He may have been too influenced by the Indian model, in which the British were in charge of military and political affairs, and the Indians could devote themselves to spiritual leadership. From the perspective of the Chinese and the Japanese, who had to build their nations from scratch, a people who did not worry about their political subjugation and spoke instead of spiritual liberation were indeed very ‘lost’.

At the same time, to see Tagore as an uncompromising foe of Western knowledge was to seriously misread his worldview. As late as 1921, he was writing disparagingly about Gandhi’s freedom movement to a friend: ‘Our present struggle to alienate our heart and mind from the West is an attempt at spiritual suicide.’40 Nor was Tagore an apolitical mystic from a lost country. He was more than alert to the Chinese sense of shame and humiliation. Passing through Hong Kong on his way to Japan in 1916, he had deplored the ‘religion of the slave’ that made a Sikh assault a Chinese labourer. Speaking of Indian collaborators with British imperialists, he lamented that ‘when the English went to snatch away Hong Kong from China, it was they who beat ‘China … they have taken upon [themselves] the responsibility of insulting China’.41 He felt the pain of the destruction of the Summer Palace no less keenly than Chinese nationalists, remembering ‘how the European imperialists had razed [it] to dust … how they had torn to pieces, burned, devastated and looted the age-old art objects. Such things would never be created in the world again.’

He followed the stalemate between England and Ireland, remarking that the former ‘is a python which refuses to disgorge this living creature which struggles to live its separate life’.42 Received by dignitaries during his visit to Persia and Iraq in 1932, he was not indifferent to the new form of warfare being tried out on hapless villagers:

the men, women and children done to death there meet their fate by a decree from the stratosphere of British imperialism – which finds it easy to shower death because of its distance from its individual victims. So

dim and insignificant do those unskilled in the modern arts of killing appear to those who glory in such skill!43

Moreover, unlike the caricature of him among Chinese radicals, Tagore was ready, too, to appreciate new social and political experiments like the Russian Revolution. Years after Tagore left China Lu Xun acknowledged, ‘I did not see this clearly before, now I know that he is also an anti-imperialist.’44 His brother Zhou Zuoren denounced Tagore’s critics who ‘think they are scientific thinkers and Westernizers, but they lack the spirit of scepticism and toleration’. But in 1924 the young radicals had succeeded in popularizing their misperceptions; deeply shaken by the assaults on him, Tagore cancelled the rest of his lectures. In his last public appearance, he addressed the controversy caused by his visit. Young people, he conceded, are attracted by the West. But he worried that ‘the traffic of ideas’ was one way, leading to the ‘gambling den of commerce and politics, to the furious competition of suicide in the area of military lunacy’. Tagore insisted that ‘in order to save us from the anarchy of weak thought we must stand up today and judge the West’; ‘We must find our voice to be able to say to the West: “You may force your things into our homes, you may obstruct our prospects of life – but we judge you!”’45

Moving on to Japan from China in June 1924, Tagore had another opportunity to judge the West rather severely. After years of informal restrictions, the United States had finally banned Japanese immigration altogether, triggering one of the first waves of anti-Americanism that were to sweep across the country repeatedly for the next two decades. Tagore joined them in their sense of outrage over the American decision. Speaking to a large audience at the University of Tokyo, he claimed that ‘the materialistic civilization of the West, working hand in hand with its strong nationalism, has reached the heights of unreasonableness’.46 He said that on his previous trip the Japanese people had scorned his critique of nationalism, but it had been validated by the many urgent reflections worldwide on the catastrophe of the Great War. ‘Now after the war,’ he said, ‘do you not hear everywhere the denunciation of this spirit of the nation, this collective egoism of the people, which is universally hardening their hearts?’47

He spoke of those in the West who claim ‘sneeringly’ that ‘we in the East have no faith in Democracy’, and feel morally superior. ‘We who do not profess democracy,’ he asserted, ‘acknowledge our human obligations and have faith in our code of honour.’ ‘But,’ he asked, ‘are you also going to allow yourselves to be tempted by the contagion of this belief in your own hungry right of inborn superiority, bearing the false name of democracy?’48

Tagore may have been misled by the applause his words received. Japan by 1924 was a much more nationalistic country than the one he had first visited in 1916. (In fact, Tagore managed to misjudge the country’s mood on every visit except his very last in 1929, when at last he sensed it, and recoiled.) But on the whole, Tagore found the sober Japanese mood more to his taste on this second trip in 1924.

He met Toyama Mitsuru, the ultra-nationalist leader of the Black Dragons, who was dedicated to expanding Japan into the Asian mainland, and repeated his message of a spiritual revival spearheaded by Asia. Tagore had no idea that these Japanese proponents of pan-Asianism meant something far more aggressive. Passing through Japan on his way to Canada in 1929, he again spoke of the ‘hopes of Asia’, even as he warned that the Japanese ‘are following the Western model’ and getting lost in the ‘mire of Western civilization’.

Returning to Japan later the same year, Tagore began to realize the full extent to which Japan was becoming an imperialist power on the ‘Western model’. Students from Korea described to him Japanese brutality in their country, and first-hand Chinese reports revealed to him Japan’s aggressive designs on what, in 1929, had become an almost prostrate country. Meeting Toyama Mitsuru on this occasion, Tagore launched into a furious tirade: ‘You have been infected by the virus of European imperialism.’ Toyoma tried to calm him down, but Tagore declared he would never visit Japan again. His resolve was hardened by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and then its extension into China proper in 1937: the early shots in the conquest of Asia – what Japanese militarists would soon call the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.

When in 1935 an old Japanese friend of his, the poet Yonejiro Noguchi, wrote to ask him to endorse Japan’s war in China, since it was the means for ‘establishing a new great world in the Asiatic continent’, a war of ‘Asia for Asia’, Tagore replied to say that he thought

Noguchi’s conception of Asia would be ‘raised on a tower of skulls’. ‘It is true,’ he added, ‘that there are no better standards prevalent anywhere else and the so-called civilized peoples of the West are proving equally barbarous.’49 But ‘if you refer me to them, I have nothing to say’. Noguchi persisted, pointing to the threat of communism in China. Tagore responded by ‘wishing the Japanese people, whom I love, not success, but remorse’.50

Thus ended the dream of a regenerated Asian spiritual civilization. Certainly ‘spirituality’ had proved too vague a word; it could readily indicate the warrior spirit of the samurai as well as the self-control of the Brahman. There was also something fuzzy about the notion that Asian countries were joined together by immemorial cultural links established by the export of Buddhism or Chinese culture from their origin countries to the furthest peripheries of Asia.

In 1938, nearing the end of his life, Tagore despaired: ‘We are a band of hapless people, where would we look up to? The days of staring at Japan are over.’51 Three years later, he was dead. His host in China, Liang Qichao, had passed away in 1929, still relatively young at fifty-six. Four years previously, Kang Youwei had died, and Liang had delivered the funeral oration, hailing his old mentor as the pioneer of reform. The Vietnamese Phan Boi Chau, nearly executed and then politically neutered by the French, died in the old imperial city of Hue in 1940. In their last decades, most of these early advocates of internal self-strengthening had become unsympathetic to the rise of hard-edged political ideologies, and politically isolated within their own countries. Elsewhere – in Egypt, Turkey and Iran – disenchanted Islamic modernists were being pushed aside by hard-line communists, nationalists and fundamentalists. In colleges, seminaries and official trade unions, as well as in secret societies and organizations across Asia (and in the coffee houses of Paris, Berlin and London) a new kind of militant nationalist and anti-imperialist was emerging. Many of these were the over-eager ‘schoolboys of the East’ that Tagore warned against in one of his last essays:

The carefully nurtured yet noxious plant of national egoism is shedding its seeds all over the world, making our callow schoolboys of the East

rejoice because the harvest produced by these seeds – the harvest of antipathy with its endless cycle of self-renewal – bears a western name of high-sounding distinction. Great civilizations have flourished in the past in the East as well as the West because they produced food for the spirit of man for all time … These great civilizations were at last run to death by men of the type of our precocious schoolboys of modern times, smart and superficially critical, worshippers of self, shrewd bargainers in the market of profit and power, efficient in their handling of the ephemeral, who … eventually, driven by suicidal forces of passion, set their neighbours’ houses on fire and were themselves enveloped by flames.52

These may have seemed melodramatic words in 1938. But Tagore had remained preternaturally alert to, and fearful of, the violent hatreds still to be unleashed across Asia, beginning with the Japanese invasion of the Asian mainland. Addressing a dinner-party audience in New York in 1930 that included Franklin D. Roosevelt, Henry Morgenthau and Sinclair Lewis, Tagore had conceded that ‘the age belongs to the West and humanity must be grateful to you for your science’. But, he added, ‘you have exploited those who are helpless and humiliated those who are unfortunate with this gift’.53 As events in the next decade would prove, liberation for many Asians would be synonymous with turning the tables and subjecting their Western masters to extreme humiliation. This extraordinary reversal would occur more quickly than anyone expected, and more brutally than Tagore feared. And Japan would be its principal agent.