CHAPTER XV — THE THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES

TOWARDS the middle of May it was decided that all three Brigades of Tanks, that is, the whole Heavy Branch, should take part in the forthcoming operations of the Fifth Army east of Ypres, and that two of these brigades should assemble in Oosthoek wood and the third at Ouderdom. To initiate preparations an advanced headquarters was opened at Poperinghe early in June, and on the 22nd of this month the brigade advanced parties moved to the Ypres area.

After the battle of Messines, the 2nd Brigade (A and B Battalions) had assembled at Ouderdom, so the present concentration only involved moving the 1st Brigade (D and G Battalions), and the 3rd Brigade (F and C Battalions) to Oosthoek. Seven trains were required for each of these Brigades.

At about this time it was decided that the 1st Brigade should be allotted to the XVIIIth Corps,

the 3rd Brigade to the XIXth Corps, and the 2nd Brigade to the IInd Corps; brigade commanders were, therefore, instructed to place themselves in touch with these corps and commence preparations.

The preparations required varied considerably from those for former battles. The Ypres-Comines canal, running parallel to the front of attack, formed a considerable obstacle to tank movement; consequently, causeways had to be built over the canal as well as over the Kemmelbeek and the Lombartbeek. This work was carried out by the 184th Tunnelling Company, which was attached to the Heavy Branch for the purpose. The work this unit carried out, normally under severe shell fire, was most efficient and praiseworthy. Besides the building of these causeways and the usual supply preparations, thoroughly efficient signalling communication was arranged for, including the use of a certain number of tanks fitted with wireless installations.

The reconnaissance work of the battalions was greatly facilitated by that already carried out by

the advanced headquarters party. Oblique aerial photographs were provided for each tank commander, and plasticine models of every part of the eventual battle area were carefully prepared, the shelled zone being stencilled on them as the bombardment proceeded. To facilitate the movement of tanks over the battlefield a new system was made use of by which a list of compass bearings from well-defined points to a number of features in the enemy’s territory was prepared, thus enabling direction to be picked up easily. The distribution of information was more rapid than it had been on previous occasions. Constant discussions between the Brigade and Battalion Reconnaissance officers led to a complete liaison; in fact, everything possible was done to make the tank operations a success; further, there was ample time to do it in.

The Fifth Army attack was to be carried out on well recognised lines; namely, a lengthy artillery preparation followed by an infantry attack on a large scale and infantry exploitation until

resistance became severe, when the advance would be halted and a further organised attack prepared on the same scale. This methodical progression was to be continued until the exhaustion of the German reserves

{24}

and moral created a situation which would enable a complete break-through to be effected.

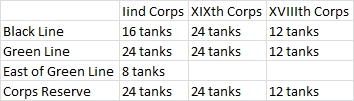

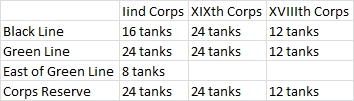

The number of tanks allotted to the three attacking Corps was as follows: seventy-two to each of the IInd and XIXth Corps, thirty-six to the XVIIIth, and thirty-six to be held in Army reserve. These were subdivided according to objectives, namely:

The Corps objectives and the allotment of tanks to Divisions were as follows:

In the IInd Corps the 24th and 30th Divisions supported by the 18th Division were to attack on

the right, and the 8th Division, supported by the 25th Division, on the left. The general objective of the operations was the capture of the Broodseinde ridge, and the protection of the right flank of the Fifth Army. The allotment of tanks to Divisions was: twelve to the 30th Division, eight to the 18th Division, twenty-four to the 8th Division, and four to the 24th Division.

In the XIXth Corps the 15th Division was on the right and the 55th Division on the left, with the 16th and 36th Divisions in reserve. The objective of this Corps was to capture and hold a section of the enemy’s third-line system known as the Gheluvelt-Langemarck line. Twenty-four tanks were allotted to each of the attacking divisions.

In the XVIIIth Corps the 39th Division was on the right and the 51st Division on the left, with the 11th and 48th Division in reserve. The main objective was the Green Line; but should this be successfully occupied the 51st Division was to seize the crossings of the river Steenbeek at Mon du Rasta and the Military Road, and establish a line

beyond that river from which a further advance could be made on to the Gheluvelt-Langemarck line; the 39th Division on the left conforming by throwing out posts beyond the Green Line. Eight tanks were allotted to the 51st Division and sixteen to the 39th Division.

The dead level of Northern Flanders is broken by one solitary chain of hills, a crescent in shape, with its cusps as Cassel and Dixmude. From Cassel to Kemmel hill had been ours since 1914; to this the Messines-Wytschaete ridge was added, as we have seen in June 1917; now all that remained was the extension of this ridge northwards from about Hooge to Dixmude. The territory lying within the crescent was practically all reclaimed swamp land, including Ypres and reaching back as far as to St. Omer, both of which, a few hundred years ago, were seaports. All agriculture in this area depended on careful drainage, the water being carried away by innumerable dikes. So important was the maintenance of this drainage system considered

that in normal times a Belgian farmer who allowed his dikes to fall into disrepair was heavily fined.

The frontage of attack of the Fifth Army extended from the Ypres-Comines canal to Wiltje cabaret. On the left the French were co-operating, attacking towards Houthulst forest, and on the right the Second Army was restricted to an all but passive artillery rôle. This frontage was flanked by two strong positions, the Polygonveld and Houthulst forest, which formed two bastions with a semi-circular ridge of ground as a curtain between them; in front of this low curtain ran a broad moat—the valley of the Steenbeek and its small tributaries.

From the tank point of view the Third Battle of Ypres is a complete study of how to. move thirty tons of metal through a morass of mud and water. The area east of the canal had, through neglect and daily shell fire, been getting steadily worse since 1914, but as late as June 1917 it was still sufficiently well drained to be negotiable throughout, by the end of July it had practically

reverted to its primal condition of a vast swamp; this was due to the intensity of our artillery fire.

It must be remembered at this time the only means accepted whereby to initiate a battle was a prolonged artillery bombardment; sufficient reliance not as yet being placed in tanks on account of their liability to break down.

{25}

The present battle was preceded by the longest bombardment ever carried out by the British Army, eight days counter-battery work being followed by sixteen days intense bombardment. The effect of this cannonade was to destroy the drainage system and to produce water in the shell-holes formed even before the rain fell. Slight showers fell on the 29th and 30th, and a heavy storm of rain on July 31

.

A study of the ground on the fronts of the three attacking corps is interesting. On the IInd Corps

front the ground was broken by swamps and woods, only three approaches were possible for tanks, and these formed dangerous defiles. On the XIXth Corps front the valley of the Steenbeek was in a terrible condition, innumerable shell-holes and puddles of water existed, the drainage of the Steenbeek having been seriously affected by the shelling. On that of the XVIIIth Corps front the ground between our front line and the Steen-beck was cut up and sodden. The Steenbeek itself was a difficult obstacle, and could scarcely have been negotiated without the new unditching gear which had been produced since the battle of Messines. The only good crossing was at St. Julien, and this formed a dangerous defile.

Zero hour was at 3.50 a.m., and it was still dark when the tanks, which had by July 31 assembled cast of the canal, moved forward behind the attacking infantry.

Briefly, the attack on July 31, in spite of the fact that there are fifty-one recorded occasions upon which individual tanks assisted the infantry, may

be classed as a failure. On the IInd Corps front, because of the had going, the tanks arrived late, and owing to the infantry being hung up, they were caught in the defiles by hostile artillery fire and suffered considerable casualties in the neighbourhood of Hooge. They undoubtedly drew heavy shell fire away from the infantry, but the enemy appeared to be ready to deal with them as soon as they reached certain localities and knocked them out one by one. On the XIXth Corps front they were more successful. At the assault on the Frezenberg redoubt they rendered the greatest assistance to the infantry, who would have suffered severely had not tanks come to their rescue. Several enemy’s counter-attacks were broken by the tanks, and Spree farm, Capricorn keep, and Bank farm were reduced with their assistance. On the XVIIIth Corps front at English trees and Macdonald’s wood several machine guns were silenced; the arrival of a tank at Ferdinand’s farm caused the enemy to evacuate the right bank of the Steenbeek in this neighbourhood. The attack on St.

Julien and Alberta would have cost the infantry heavy casualties had not two tanks come up at the critical moment and rendered assistance. At Alberta strong wire still existed, and this farm was defended by concrete machine-gun emplacements with good dug-outs. The two tanks which arrived here went forward through our own protective barrage, rolled flat the wire and attacked the ruins by opening fire at very close range, with the result that the enemy was driven into his dug-outs and was a little later on taken prisoner by our infantry.

The main lessons learnt from this day’s fighting were—the unsuitability of the Mark IV tank to swamp warfare; the danger of attempting to move tanks through defiles which are swept by hostile artillery fire; the necessity for immediate infantry co-operation whenever the presence of a tank forced an opening, and the continued moral effect of the tank on both the enemy and our own troops.

The next attack in which tanks took part was on August 19, and in spite of the appalling condition of the ground, for it had now been steadily raining for

three weeks, a very memorable feat of arms was accomplished. The 48th Division of the XVIIIth Corps had been ordered to execute an attack against certain strongly defended works, and, as it was reckoned that this attack might cost in casualties from 600 to 1,000 men, it was decided to make it a tank operation in spite of the fact that the tanks would have to work along the remains of the roads in place of over the open country. Four tanks were detailed to operate against Hillock farm, Triangle farm, Mon du Hibou, and the Cockcroft; four against Winnipeg cemetery, Springfield, and Vancouver, and four to be kept in reserve at California trench. The operation was to be covered by a smoke barrage, and the infantry were to follow the tanks and make good the strong points captured

.

Eleven tanks entered St. Julien at 4.45 a.m., three ditched, and eight emerged on the St. Julien-Poelcappelle road, when down came the smoke barrage, throwing a complete cloud on the far side of the objectives; at 6 a:m. Hillock farm was occupied, at 6.15 a.m. Mon du Hibou was reduced, and five minutes later the garrison of Triangle farm, putting up a fight, were bayoneted. Thus one point after another was captured, the tanks driving the garrisons underground or away, and the infantry following and making good what the tanks had made possible. In this action the most remarkable results were obtained at very little cost, for instead of 600 casualties the infantry following the tanks only sustained fifteen!

From this date on to October 9 tanks took part in eleven further actions, the majority being fought on the XVIIIth Corps front by the 1st Tank Brigade. On August 22 a particularly plucky fight was put up by a single tank. This machine became ditched in the vicinity of a strong point called Gallipoli, and, for sixty-eight hours on end, fought

the enemy, breaking up several counter-attacks; eventually the crew, running short of ammunition, withdrew to our own lines on the night of August 24-25.

Of the attacks which were made with tanks in the latter half of September and the beginning of October, the majority took place along the Poelcappelle road, the most successful being fought on October 4. Of this attack the XVIIIth Corps Commander reported that “the tanks in Poelcappelle were a decisive factor in our success on the left flank”; and their moral effect on the enemy was illustrated by the statement of a captured German officer who gave as the reason of his surrender—“There were tanks—so my company sur-rendered—I also.”

It is almost impossible to give any idea of the difficulty of these latter operations or of the “grit” required to carry them out. Roads, if they could be called by such a name at all, were few and far between in the salient caused by the repeated attacks during the battle. This salient had a base of

some 20,000 yards and was only 8,000 deep at the beginning of October, at which date the enemy could still obtain extensive observation over it from the Passchendaele ridge. The ground in between these roads being impassable swamps, all movement had to proceed along them, consequently they formed standing targets for the German gunners to direct their fire on. One night, at about this period of the battle, a tank engineer officer was instructed to proceed to Poelcappelle to superintend the demolition of some tanks which were blocking the road near the western entrance to the village. His description of it at night-time is worth recording.

“I left St. Julien in the dark, having been informed that our guns were not going to fire. I waded up the road, which was swimming in a foot or two of slush, frequently I would stumble into a shell-hole hidden by the mud. The road was a complete shambles and strewn with debris, broken vehicles, dead and dying horses and men. I must have passed hundreds of them as well as bits of

men and animals littered everywhere. As I neared Poelcappelle our guns started to fire: at once the Germans replied, pouring shells on and around the road, the flashes of the bursting shells were all round me. I cannot describe what it felt like, the nearest approach of a picture I can give is that it was like standing in the centre of the flame of a gigantic Primus stove. As I neared the derelict tanks, the scene became truly appalling: wounded men lay drowned in the mud, others were stumbling and falling through exhaustion, others crawled and rested themselves up against the dead to raise themselves a little above the slush. On reaching the tanks I found them surrounded by the dead and dying; men had crawled to them for what shelter they would afford. The nearest tank was a female, her left sponson doors were open, out of these protruded four pairs of legs, exhausted and wounded men had sought refuge in this machine, and dead and dying lay in a jumbled heap inside.”

Whatever history may record of the Third Battle of Ypres, one fact certainly will not be overlooked or

forgotten, namely: that men who could continue for three months to attack under the conditions which characterised this most terrible battle of the war must indeed belong to an invincible stock.