CHAPTER XIX — THE BATTLE OF CAMBRAI

ON October 20, the project, which had been constantly in the mind of the General Staff of the Tank Corps for nearly three months and in anticipation of which preparations had already been undertaken, was approved of, and its date fixed for November 20.

The battle was to be based on tanks and led by them. There was to be no preliminary artillery bombardment; the day the Tank Corps had prayed for, for nearly a year, was at last fixed, and its success depended on the following three factors:

- That the attack was a surprise.

- That the tanks were able to cross the great trenches of the Hindenburg system.

- That the infantry possessed sufficient confidence in the tanks to follow them.

The following difficulties had to be overcome before these requirements could be met. The tanks,

on October 20, were scattered over a considerable area: some were at Ypres, others near Lens, and others at Bermicourt. These would all have to be assembled not at suitable entraining stations, as is usually the case, but at various training areas so that co-operative training with the infantry could take place. This was of first importance, for success depended as much on the confidence of the infantry in the tanks as on the surprise of the attack. At these training centres, tanks would have to be completely overhauled and fitted with a special device to assist them in crossing the Hindenburg trenches, which were known, in many places, to be over 12 ft. wide, and the span of the Mark IV machine was only 10 ft. This device consisted in binding together by means of chains some seventy-five ordinary fascines, thus making one tank fascine, a great bundle of brushwood 4 ½ ft. in diameter and 10 ft. long; this bundle was carried on the nose of the tank and, when a large trench was encountered, was cast into it by pulling a quick release inside the tank. As already described these ta

nk fascines and the “fitments” necessary to fix and release them were made by the Tank Corps Central Workshops.

Before the infantry assembled for training a new tactics had to be devised, not only to meet the conditions which would be encountered but to fit the limitations imposed upon the tank by it being able to carry only one tank fascine. Once this fascine was cast it could not be picked up again without considerable difficulty.

Briefly, the tactics decided on were worked out to meet the following requirements: “To effect a penetration of four systems of trenches in a few hours without any type of artillery preparation.” They were as follows:

Each objective was divided up into tank section attack areas, according to the number of tactical points in the objective, and a separate echelon, or line, of tanks was allotted to each objective. Each section was to consist of three machines—one Advanced Guard tank and two Infantry tanks (also called Main Body tanks); this was agreed to on

account of there not being sufficient tanks in France to bring sections up to four machines apiece.

The duty of the Advanced Guard tank was to keep down the enemy’s fire and to protect the Infantry tanks as they led the infantry through the enemy’s wire and over his trenches. The allotment of the infantry to tanks depended on the strength of the objective to be attacked, and the nature of the approaches; their formation was that of sections in single file with a leader to each file. They were organised in three forces: trench clearers to operate with the tanks; trench stops to block the trenches at various points, and trench supports to garrison the captured trench and form an advanced guard to the next echelon of tanks and infantry passing through.

The whole operation was divided into three phases: the Assembly, the Approach, and the Attack. The first was carried out at night time and was a parade drill, the infantry falling in behind the tanks on tape lines, connected with their starting-points by taped routes. The Approach was

slow and orderly, the infantry holding themselves in readiness to act on their own initiative. The Attack was regulated so as to economise tank fascines; it was carried out as follows. The Advanced Guard tank went straight forward through the enemy’s wire and, turning to the left, without crossing the trench in front of it, opened right sponson broadsides. The Infantry tanks then made for the same spot: the left-hand one, crossing the wire, approached the trench and cast its fascine, then crossed over the fascine and, turning to the left, worked down the fire trench and round its allotted objective; the second Infantry tank crossed over the fascine of the first and made for the enemy’s support trench, cast its fascine, and, crossing, did likewise. Meanwhile the Advanced Guard tank had swung round, and crossing over the fascines of the two Infantry tanks moved forward with its own fascine still in position. When the two Infantry tanks met they formed up behind the Advanced Guard tank and awaited orders

.

In training the infantry the following exercises were carried out:

- Assembly of infantry behind tanks.

- Advance to attack behind tanks.

- Passing through wire crushed down by tanks.

- Clearing up a trench sector under protection of tanks.

To enable them to work quickly in section single files and to form from these into section lines, a simple platoon drill was issued, and it is interesting to note that this drill was based on a very similar one described by Xenophon in his “Cyropaedia” and attributed to King Cyrus (circa

500 B.C.).

Whilst training was being arranged by the Tank Corps General Staff the Administrative Staff was preparing for the railway concentration, which was by no means an easy problem.

The difficulties of concentrating a large number of tanks in the area of operations was accentuated by the dispersion of the Tank Corps and the shortage of trucks; this shortage was made good by

collecting a number of old French heavy trucks; these, however, did not prove at all satisfactory as they were too light. In spite of these difficulties the whole of the units of the Tank Corps were concentrated in their training areas by November 5.

In order to make the most of the available truckage and the time attainable for infantry training, it was decided to concentrate three-quarters of the whole number of tanks to be used, i.e.

twenty-seven train loads, at the Plateau station by November 14 (Z-6 days); to move these to their final detraining stations on Z-4, Z-3, and Z-2 days; and to move the remaining quarter, i.e.

nine train loads, from the training areas to the detraining stations on Z-5 day. The detraining stations selected were Ruyaulcourt and Bertincourt for the 1st Brigade, Sorel and Ytres for the 2nd Brigade, and Old and New Heudicourt for the 3rd Brigade. At all these stations detraining ramps and sidings were built or improved. In all, thirty-six tank trains were run, and except for two or three

minor accidents the move was carried out to programme. This was chiefly due to the excellent work of the Third Army Transportation Staff.

Supply arrangements were divided under two main headings: supply by light railways and supply in the field by supply tanks. The main dumps selected were at Havrincourt wood for the 1st Brigade, Dessart wood for the 2nd, and Villers Guislain and Gouzeaucourt for the 3rd Brigade, A few of the items dumped were 165,000 gallons of petrol, 55,000 lb. of grease, 5,000,000 rounds of S.A.A., and 54,000 rounds of 6-pounder ammunition. Without the assistance of the light railways this dumping would hardly have been possible. On November 30 a S.O.S. call for petrol was made on Ruyaulcourt. A train was loaded, despatched 3¡ miles, and the petrol delivered in just under one hour. This is a fair example of the magnificent work consistently carried out by the Third Army light railways during the battle of Cambrai

.

The Third Army plan of operations was as follows:

- To break the German defensive system between the canal St. Quentin and the canal Du Nord.

- To seize Cambrai, Bourlon wood, and the passages over the river Sensée.

- To cut off the Germans in the area south of the Sensée and west of the canal Du Nord.

- To exploit the success towards Valenciennes.

This operation, for its initial success, depended on the penetration of all lines of defences, including the Masnières-Beaurevoir line, which in its turn depended on the seizing of the bridges at Masnières and Marcoing.

The force allotted for this attack was—two corps of three infantry divisions each; the Tank Corps of nine battalions-378 fighting tanks and 98 administrative machines; a cavalry corps, and 1,000 guns.

The attack was to be carried out in three phases. In the first the infantry were to occupy the

line Crèvecœur, Masnières, Marcoing, Flesquières, canal Du Nord; the leading cavalry division was then to push through at Masnières and Marcoing, capture Cambrai, Paillencourt, and Pailluel (crossing over the river Sensée), and move with its right on Valenciennes; whilst this was in progress the IIIrd Corps, which formed the right wing of the Third Army, was to form a defensive flank on the line Crèvecœur, La Belle Etoile, Iwuy; the cavalry were then to cut the Valenciennes-Douai line and so facilitate the advance of the IIIrd Corps in a northeasterly direction. The second and third phases were to be carried out by the IVth Corps, which formed the left wing of the Third Army, and were to consist firstly in opening the Bapaume-Cambrai road and occupying Bourlon and Inchy, and secondly, in opening the Arras-Cambrai road and advancing on the Sensée canal and so to cut off the German forces west of the canal Du Nord.

The ground to be fought over consisted chiefly in open, rolling downland, very lightly shelled, and consequently most suitable to tank movement. The

main tactical features were the two canals which practically prohibited the formation of tank offensive flanks and so strategically were a distinct disadvantage to what was meant to be a decisive battle. Between these two canals were two important features—the Flesquiéres-Havrincourt ridge and Bourlon hill. A third very important feature, known as the Rumilly-Seranvillers ridge, ran parallel to and north of the St. Quentin canal between Crèvecœur and Marcoing; without the occupation of this ridge a direct attack from the south on Bourlon hill could only take place under the greatest disadvantage.

The German defences consisted of three main lines of resistance and an outpost line: these lines were the Hindenburg Line, the Hindenburg Support Line, and the Beaurevoir-Masniéres-Bourlon line, the last being very incomplete. The trenches for the most part were sited on the reverse slopes of the main ridges, and consequently direct artillery observation on them from the British area was impossible. They were protected by immensely

thick bands and fields of wire arranged in salients so as to render their destruction most difficult. To have cut these bands by artillery fire would have required several weeks bombardment and scores of thousands of tons of ammunition.

The weather had been throughout November fine and foggy, so much so that aeroplane observation had been next to impossible. This foggy weather greatly assisted preparatory arrangements by securing them from observation.

The artillery preparations were as follows: —Over 1,000 guns of various calibres were concentrated in the Third Army area for the attack. None of these, however, were permitted to register before zero hour. Briefly the following was the artillery programme from zero hour on.

At zero the barrage was to open on the enemy’s outpost line; it was to consist of shrapnel and H.E. mixed with smoke shells. It was to move forward by jumps of approximately 250 yards at a time, standing on certain objectives for stated periods. Simultaneously with this jumping barrage smoke

screens were to be thrown up on selected localities, notably on the right flank of the IIIrd Corps and on the Flesquières ridge; counter-battery work was to open and special bombardments on prearranged localities such as bridgeheads, centres of communication, and roads likely to be used by the German reserves were to take place.

Tank Corps reconnaissances were started as early as secrecy would permit, but it was not until a few days before November 20 that commanders were allowed to reconnoitre the ground from our front-trench system. Meanwhile at the Plateau station tanks were tuned up and tank fascines fixed. All detrainments were carried out by night, the tanks being moved up to their position of assembly under cover of darkness. These positions were: Villers Guislain and Gouzeaucourt for the 3rd Brigade, Dessart wood for the 2nd Brigade, and Havrincourt wood for the 1st Brigade. At these places tanks were carefully camouflaged.

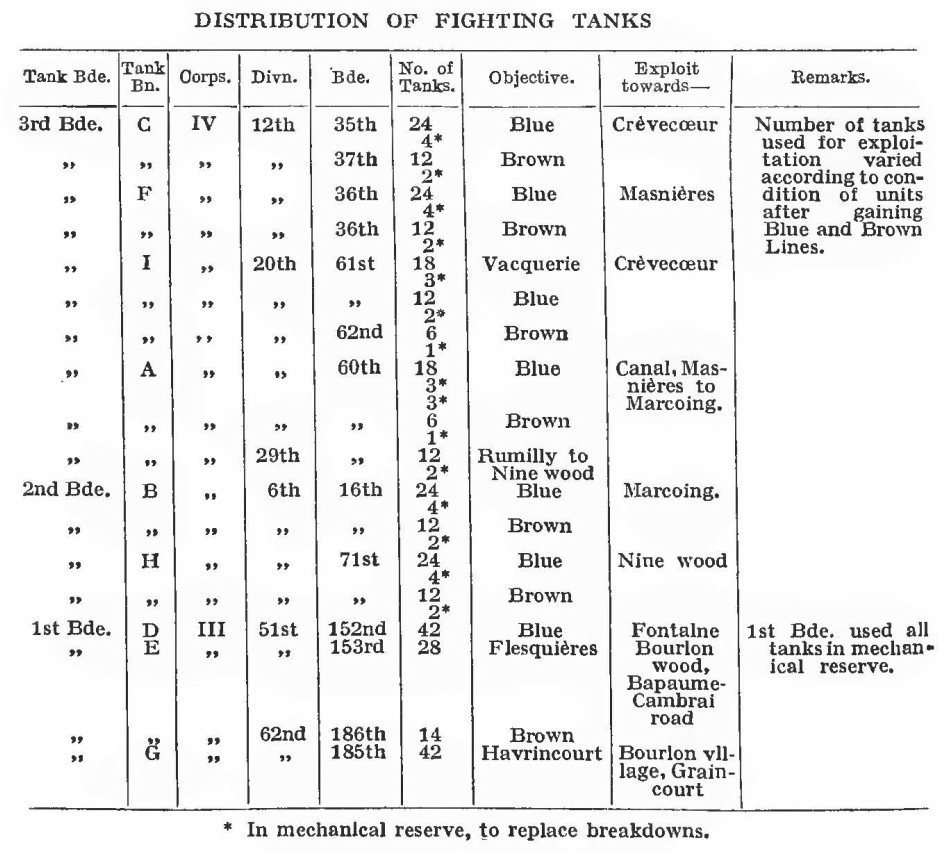

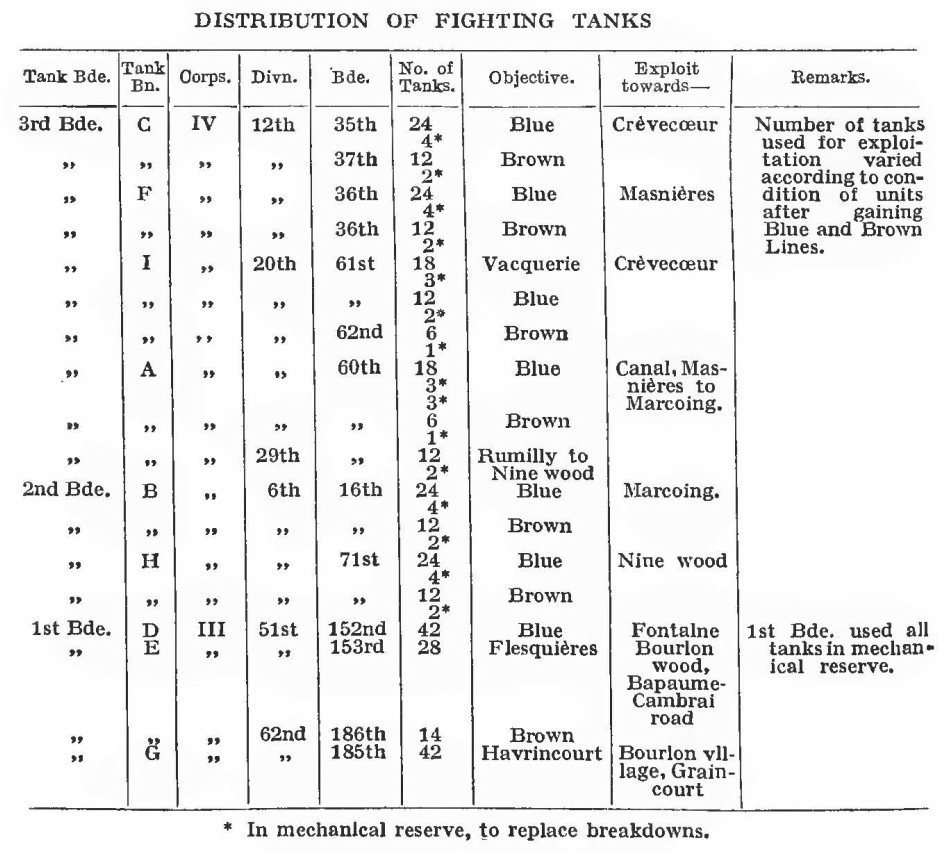

The allotment of tanks to infantry units is given in the table on page 146. Besides these, each Brigade had eighteen supply tanks or gun carriers

and three wireless-signal tanks. Thirty-two machines were specially fitted with towing gear and grapnels to clear the wire along the cavalry lines of advance; two for carrying bridging material for the cavalry and one to carry forward telephone cable for the Third Army Signal Service. The total number of tanks employed was 476 machines.

On the night of November 17-18 the enemy raided our trenches in the vicinity of Havrincourt wood and captured some of our men, and, from the documents captured during the battle, it appears that these men informed the enemy that an operation was impending; time wherein the Germans could make use of this was, however, so limited that the warning of a possible attack only reached the German firing line a few minutes before it took place.

The following night, that of the 19th-20th, was broken by a sharp burst of artillery and trench-mortar fire which died away in the early morning, and at’ 6 a.m. all was still save for the occasional rattle of a machine gun. A thick mist covered the

ground when at 6.10 a.m., ten minutes before zero hour, the tanks, which had deployed on a line some 1,000 yards from the enemy’s outpost trenches, began to move forward, infantry in section columns advancing slowly behind them. Ten minutes later, at 6.20 a.m., zero hour, the 1,000 British guns opened fire, the barrage coming down with a terrific crash about 200 yards Fin front of the tanks which were now proceeding slowly across “No Man’s Land,” led by Brigadier-General H. J. Elles, the Commander of the Tank Corps, who flew the Tank Corps colours from his tank and who on the evening before the battle had issued the following inspiring Special Order to his men:

1. To-morrow the Tank Corps will have the chance for which it has been waiting for many months—to operate on good going in the van of the battle.

2. All that hard work and ingenuity can achieve has been done in the way of preparation

.

3. It remains for unit commanders and for tank crews to complete the work by judgment and pluck in the battle itself.

4. In the light of past experience I leave the good name of the Corps with great confidence in their hands:

5. I propose leading the attack of the centre division.

HUGH ELLES, B.G. Commanding Tank Corps. November 19, 1917.

The attack was a stupendous success; as the tanks moved forward with the infantry following close behind, the enemy completely lost his balance and those who did not fly panic-stricken from the field surrendered with little or no resistance. Only at the tactical points was opposition met with. At

Lateau wood on the right of the attack heavy fighting took place, including a duel between a tank and a 5.9 in. howitzer. Turning on the tank the howitzer fired, shattering and tearing off most of the right-hand sponson of the approaching machine, but fortunately not injuring its vitals; before the gunners could reload the tank was upon them and in a few seconds the great gun was crushed in a jumbled mass amongst the brushwood surrounding it. A little to the west of this wood the tanks of F Battalion, which had topped the ridge, were speeding down on Masniéres. One approached the bridge, the key to the Rumilly-Seranvillers position, upon the capture of which so much depended. On arriving at the bridge it was found that the enemy had already blown it up, nevertheless the tank attempted to cross it; creeping down the broken girders it entered the water but failed to climb the opposite side. Other tanks arriving and not being able to cross assisted the infantry in doing so by opening a heavy covering fire. Westwards again La Vacquerie was

stormed and Marcoing was occupied. This latter village had been carefully studied beforehand and a definite scheme worked out as to where tanks should proceed after entering it. Difficult though this operation was, each position was taken up and the German engineers shot just as they were connecting up the demolition charges on the main bridge to the electric batteries.

In the Grand Ravin, which runs from Havrincourt to Marcoing, all was panic, and from Ribecourt northwards the flight of the German soldiers could be traced by the equipment they had cast off in order to speed their withdrawal. Nine wood (Bois des Neuf) was stormed, and Premy Chapel occupied. At the village of Flesquières the 51st Division, which had devised an attack formation of its own, was held up; it appears that the tanks out-distanced the infantry or that the tactics adopted did not permit of the infantry keeping close enough up to the tanks. As the tanks topped the crest they came under direct artillery fire at short range and suffered heavy casualties.

This loss would have mattered little had the infantry been close up, but, being some distance off, directly the tanks were knocked out the German machine gunners, ensconced amongst the ruins of the houses, came to life and delayed their advance until nightfall; thus Flesquières was not actually occupied until November 21.

In the village of Havrincourt some stiff fighting took place. All objectives were, however, rapidly captured, and the 62nd Division had the honour of occupying Graincourt before nightfall, thus effecting the deepest penetration attained during the attack on this day. From Graincourt several tanks pushed on towards Bourlon wood and the Cambrai road, but by this time the infantry were too exhausted to make good any further ground gained.

Meanwhile No. 3 Company of A Battalion had assisted the 29th Division on the Premy Chapel-Rumilly line, one section of tanks working towards Masnières and another co-operating with the infantry in the attack on Marcoing and the high

ground beyond. The third section attacked Nine wood, destroying many machine guns there and at the village of Noyelles, which was then occupied by our infantry. Whilst these operations were in progress the supply tanks had moved forward to their “rendezvous,” the wireless signal tanks had taken up their allotted position, one sending back the information of the capture of Marcoing within ten minutes of our infantry entering this village; and the wire-pullers cleared three broad tracks of all wire so that the cavalry could move forward. This they did, and they assembled in the Grand Ravin and in the area adjoining the village of Masnières.

By 4 p.m. on November 20, one of the most astonishing battles in all history had been won and, as far as the Tank Corps was concerned, tactically finished, for, no reserves existing, it was not possible to do more than rally the now very weary and exhausted crews, select the fittest, and patch up composite companies to continue the attack on the morrow. This was done, and on the 21st the 1st

Brigade supported the 62nd Division with twenty-five tanks in its attack on Anneux and Bourlon wood and the 2nd Brigade sent twenty-four machines against Cantaing and Fontaine-Notre-Dame, both of which villages were captured.

November 21 saw, generally speaking, the end of any co-operative action between tanks and infantry; henceforth, new infantry being employed, loss of touch and action between them and the tanks constantly resulted. Nevertheless on the 23rd a brilliant attack was executed by the 40th Division, assisted by thirty-four tanks of the 1st Brigade; this resulted in the capture of Bourlon wood. The tanks then pressed on towards the village; the infantry, however, who had suffered severe casualties in the capture of the wood, were not strong enough to secure a firm footing in it.

This day also saw desperate fighting in the village of Fontaine-Notre-Dame. Twenty-three tanks entered this village in advance of our own infantry; there they met with severe resistance, the enemy retiring to the top stories of the houses and

raining bombs and bullets down on the roofs of our machines. Our infantry, who were very exhausted, were unable to make good the ground gained, consequently, all tanks which were able to do so withdrew under cover of darkness at about 7 p.m.

On November 25 and 27 further attacks were made by tanks and infantry on Bourlon and Fontaine-Notre-Dame with varying success, but eventually both these villages remained in the hands of the enemy. So ends the first phase of the battle of Cambrai.

During the attacks which had taken place since November 21, tank units had become terribly disorganised, and by the 27th had been reduced to such a state of exhaustion that it was determined to withdraw the 1st and 2nd Brigades. This withdrawal was nearing completion when the great German counter-attack was launched early on the morning of November 30.

To appreciate this attack, it must be remembered that at this time the IIIrd and IVth Corps were occupying a very pronounced salient,

and that all fighting had, during the last few days, concentrated in the Bourlon area and had undoubtedly drawn our attention away from our right flank east of Gouzeaucourt. The plan of General von der Marwitz, the German Army Commander, was a bold one, it was none other than to capture the entire IIIrd and IVth British Corps by pinching off the salient by a dual attack, his right wing operating from Bourlon southwards and his left from Honnecourt westwards, the two attacks converging on Trescault. Between these two wings a holding attack was to be made from Masnières to La Folie wood.

The attack was launched shortly after daylight on November 30, and failed completely on the right against Bourlon wood. Here the enemy was caught by our artillery and machine guns and mown down by hundreds. On the left, however, the attack succeeded: firstly, it came as a surprise; secondly, the Germans heralded their assault by lines of low-flying aeroplanes which caused our men to keep well down in their trenches and so lose observation.

Under the protection of this aeroplane barrage and a very heavy mortar bombardment the German infantry advanced and speedily captured Villers Guislain and Gouzeaucourt.

At 9.55 a.m. a telephone message from the IIIrd Corps warned the 2nd Brigade of the attack, but, in spite of the fact that many of the machines were in a non-fighting condition, by 12.40 p.m. twenty-two tanks of B Battalion moved off towards Gouzeaucourt, rapidly followed by fourteen of A Battalion. Meanwhile the Guards Division recaptured Gouzeaucourt, so, when the tanks arrived, they were pushed out as a screen to cover the defence of this village. By 2 p.m. twenty tanks of H Battalion were ready, these moved up in support.

Early on the morning of December I, in conjunction with the Guards Division and 4th and 5th Cavalry Divisions, the 2nd Brigade delivered a counter-attack against Villers Guislain and Gauche wood. The western edge of the wood was cleared of the enemy; the tanks then proceeded through the

wood, where very heavy fighting took place. From the reports received as to the large number of dead in the wood and the numerous machine guns found in position, it is clear that the enemy had intended to hold it at all costs. Once the wood was cleared the tanks proceeded on to Villers Guislain, but being subjected to direct gun fire eventually withdrew.

The counter-attack carried out by the 2nd Brigade greatly assisted in restoring a very dangerous situation; it was a bold measure well executed, all ranks behaving with the greatest courage and determination under difficult and unexpected circumstances and amidst the greatest confusion caused by the success of the German attack; every tank crew of every movable machine had but one thought, namely, to move eastward and attack the enemy. This they did, and it is a remarkable fact that, though at 8 a.m. on November 30 not one machine of the Brigade was in a fit state or fully equipped for action, by 6 a.m. on the following day no fewer than seventy-three

tanks had been launched against the enemy with decisive effect.

Thus ended the first great tank battle in the whole history of warfare, and, whatever may be the future historian’s dictum as to its value, it must ever rank as one of the most remarkable battles ever fought. On November 20, from a base of some 13,000 yards in width, a penetration of no less than 10,000 yards was effected in twelve hours; at the Third Battle of Ypres a similar penetration took three months. Eight thousand prisoners and 100 guns were captured, and these prisoners alone were nearly double the casualties suffered by the IIIrd and IVth Corps during the first day of the battle. It is an interesting point to remember that in this battle the attacking infantry were assisted by 690 officers and 3,500 other ranks of the Tank Corps, a little over 4,000 men, or the strength of a strong infantry brigade, and that these men replaced artillery wire-cutting and rendered unnecessary the old preliminary bombardment. More than this, by keeping close to the infantry they effected a much

higher co-operation than had ever before been attainable with artillery. When on November 21 the bells of London pealed forth in celebration of the victory of Cambrai, consciously or unconsciously to their listeners they tolled out an old tactics and rang in a new—Cambrai had become the Valmy of a new epoch in war, the epoch of the mechanical engineer.