CHAPTER XXVII — THE BATTLES OF HAMEL AND MOREUIL

DURING June and July three tank actions were fought: the first was a night raid on June 22-23, the second the battle of Hamel, and the third the battle of Moreuil or Sauvillers.

The night raid is interesting in that it was the first occasion in the history of the Tank Corps in France upon which tanks were definitely allotted to work at night. The raid was carried out against the enemy’s defences near Bucquoy by five platoons of infantry and five female tanks. Its object was to capture or kill the garrisons of a series of posts. The raid took place at 11.25 p.m. A heavy barrage of trench-mortar and machine-gun fire was met with at a place called Dolls’ House in “No Man’s Land”: here the infantry were held up, and though reinforced were unable to advance further. The tanks, thereupon, pushed on and carried out the

attack in accordance with their orders. It is worthy of note that not a single tank was damaged by the trench-mortar barrage, which was very heavy. The tanks encountered several parties of the enemy and undoubtedly caused a number of casualties. One tank was attacked by a party of the enemy who were shot down by revolver fire; later on this tank rescued a wounded platoon commander who had been captured by the Germans.

This raid is interesting in that it showed the possibility of manoeuvring tanks in the dark through the enemy’s lines, and also the great security afforded to the tank by the darkness.

The battle of Hamel, which was fought on July 4, was the first occasion upon which the Mark V machine went into action. Much was expected of it, and it more than justified all expectations. The object of the attack was a twofold one—firstly, to nip off a salient between the river Somme and the Villers-Bretonneux-Warfusée road; secondly, to restore the confidence of the Australian Corps in tanks, a confidence which had been badly shaken by the Bullecourt reverse in 1917.

As soon as the attack was decided on the training of the Australians with the tanks was commenced at Vaux en Amienois, the headquarters of the 5th Tank Brigade. Tank units for this purpose were affiliated to Australian units and by this means a close comradeship was cultivated.

The general plan of operations was for the 5th Tank Brigade to support the advance of the 4th Australian Division in the attack against the Hamel spur running from the main Villers-Bretonneux plateau to the river Somme. The frontage was about 5,500 yards, extending to 7,500

yards on the final objective, the depth of which was 2,500 yards. The main tactical features in the area were Vaire wood, Hamel wood, Pear-Shape trench, and Hamel village. There was no defined system of trenches to attack except the old British line just east of Hamel, which had been originally sited to obtain observation eastwards. The remainder of the area was held by means of machine-gun nests.

Five companies of 60 tanks in all were employed in the attack; these were divided into two waves—a first-line wave of 48 and a reserve wave of 12 machines. Their distribution was as follows:

6th A.I. Brigade—2 Sections (6 tanks).

4th A.I. Brigade—1 Company (12 tanks).

11th A.I. Brigade—6 Sections (18 tanks).

Liaison between 4th and 11th Brigades—1 Company (12 tanks).

Reserves—1 Company (12 tanks).

The co-operation of the artillery was divided under the headings of a rolling barrage and the production of smoke screens. Behind the former the infantry were to advance followed by the tanks, which were only to pass ahead of them when

resistance was encountered. This arrangement was not a good one and was an inheritance of the Bullecourt distrust. The latter were to be formed on the high ground west of Warfusée-Abancourt and north of the Somme and south of Morlancourt. Once the final objective was gained a standing barrage was to be formed to cover consolidation.

As the entire operation was of a very limited character an extensive system of supply dumps was not necessary, so instead each fighting tank carried forward ammunition and water for the infantry and four supply tanks were detailed to carry R.E. material and other stores. Each of these eventually delivered a load of about 12,500 lb. within 500 yards of the final objective, and within half an hour of its capture. The total load delivered on July 4, at 40 lb. per man, represented the loads of a carrying party 1,250 men strong. Theo number of men used in these supply tanks was twenty-four.

The tanks assembled at the villages of Hamelet and Fouilloy on the night of July 2-3, without hostile interference. On the following night they

moved forward to a line approximately 1,000 yards west of the infantry starting-line under cover of aeroplanes which, flying over the enemy, drowned the noise of the tank engines.

Zero hour was fixed for 3.10 a.m. and tanks were timed to leave their starting-line at 3.2 a.m. under cover of artillery harassing fire, which had been carried out on previous mornings in order to accustom the enemy to it. This fire lasted seven minutes, then a pause of one minute occurred, to be followed by barrage fire on the enemy’s front line for four minutes. This allowed twelve minutes for the tanks to advance an average distance of 1,200 yards before reaching the infantry line at zero plus four minutes, when the barrage was to lift. All tanks were on the starting-line up to time, which is a compliment to the increased reliability of the Mark V machine over all previous types

.

As the barrage lifted the infantry and tanks moved forward. The position of the tanks in relation to the infantry varied, but, generally speaking, the tanks were in front of the infantry and immediately behind the bursting shells. The enemy’s machine-gunners fought tenaciously, and in several cases either held up the infantry, or would have inflicted severe casualties on them, if tanks had not been there to destroy them. The manoeuvring power of the Mark V tank was clearly demonstrated in all cases where the infantry were held up by machine guns, it enabled the tanks to drive over the gunners before they could get away.

There were a great number of cases in which the German machine guns were run over and their detachments crushed. Driving over machine-gun emplacements was the feature of this attack; it eliminated all chance of the enemy “coming to life” again after the attack had passed by.

Tanks detailed for the right flank had severe fighting and did great execution, their action being of the greatest service. The tanks detailed to support the infantry battalions passing round Vaire and Hamel woods and Hamel village guarded their flanks whilst this manoeuvre was in operation.

The tank attack came as a great surprise to the Germans and all objectives were taken up to scheduled time. The enemy suffered heavy loss, and, besides those killed, 1,500 prisoners were captured. The 4th Australian Division had 672 officers and other ranks killed and wounded, and the 5th Brigade had only 16 men wounded and 5 machines hit. These tanks were all salved by the night of July 6-7

.

The co-operation between the infantry and tanks was as near perfect as it could be; all ranks of the tank crews operating were impressed by the superb moral of the Australian troops, who never considered that the presence of the tanks exonerated them from fighting, and who took instant advantage of any opportunity created by the tanks. From this day on the fastest comradeship has existed between the Tank and Australian Corps. Bullecourt was forgotten, and from the psychological point of view this was an important objective to have gained prior to the great attack in August.

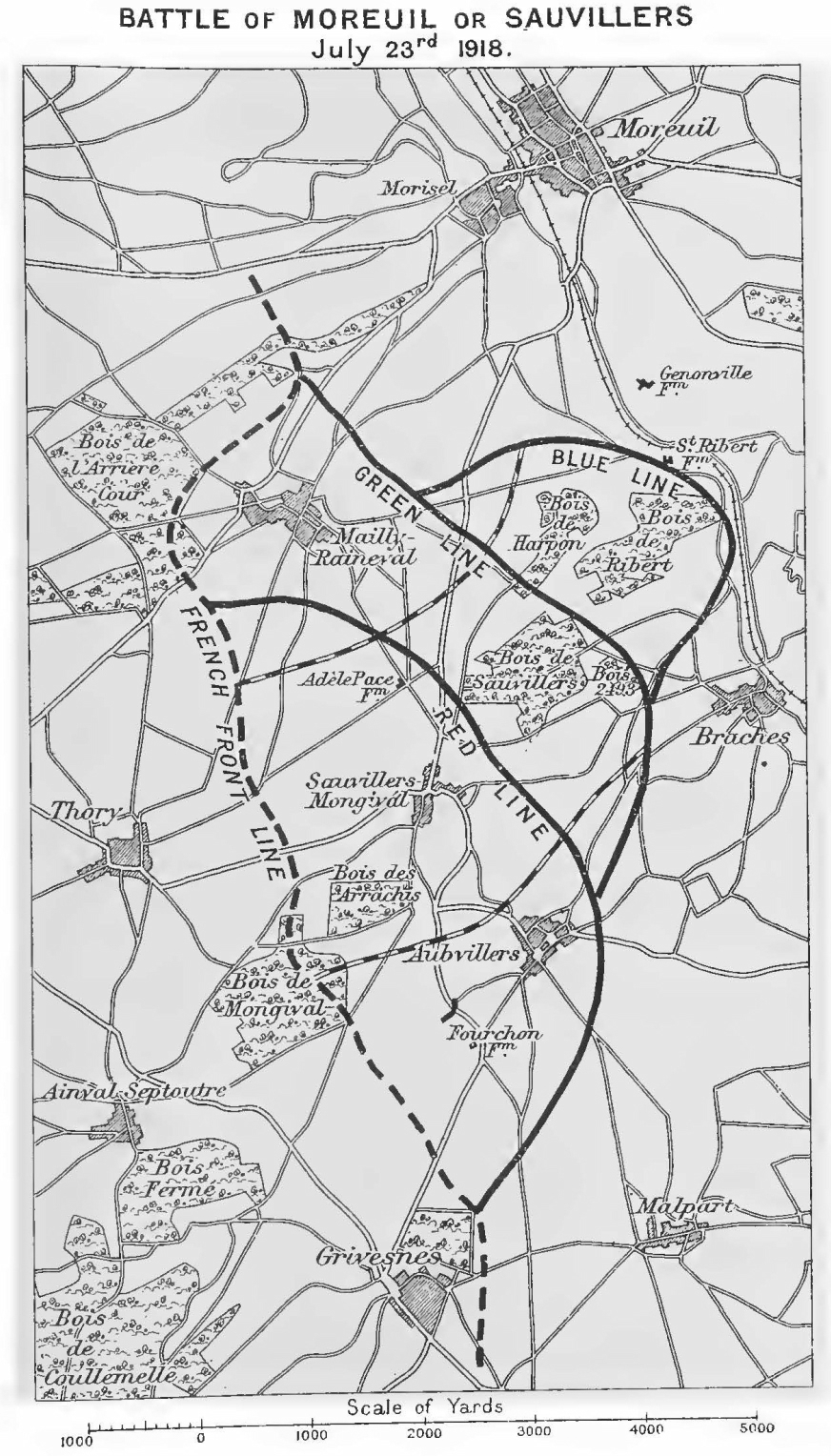

The second battle in which the Tank Corps took part in July was the battle of Moreuil or Sauvillers; it is of particular interest, for it was the only occasion during the war in which our tanks, in any numbers, operated with the French Army.

Another interesting point connected with this attack was the rapidity with which it was mounted

.

At 2.30 p.m. on July 17 the 5th Tank Brigade Commander was informed that he was to prepare forthwith to co-operate in an attack to be made by the IXth Corps of the First French Army, and, for this purpose, the 9th Battalion of the 3rd Tank Brigade was to be placed under his command and that he and this battalion would come under the orders of the 3rd French Infantry Division.

The object of the operation was a threefold one:

- To seize the St. Ribert wood with the object of outflanking Mailly-Raineval from the south.

- To capture the German batteries in the neighbourhood of St. Ribert or to force them to withdraw.

- To advance the French field batteries eastwards in order to bring fire to bear on the ridge which dominates the right bank of the river Avre.

The three French Divisions attacking were the 152nd Division on the right, the 3rd in the centre, and the 15th on the left. Their respective frontages were 950, 2,000, and 800 metres. The greatest depth of the attack was 3,000 metres

.

The operation was to be launched as a surprise, after a short and intense artillery preparation; the main objectives were to be captured by encircling them and then “mopping” them up.

There were three objectives: The first included Bois des Arrachis, Sauvillers, Mongival village, Adelpare farm and Ouvrage-des-Trois-Bouqueteaux; twelve tanks and four battalions of infantry were detailed for this. The second included the clearing of the plateau to the north of the Bois-de-Sauvillers and the capture of the south-west corner of the Bois-de-Harpon; the number of tanks allotted to this objective was twenty-four, with four fresh infantry battalions. The third, known as the Blue Line, an outpost line covering the second objective, was to be occupied by eight strong infantry patrols and all available machines

.

The attack was to be preceded by one hour’s intensive bombardment, including heavy counter-battery fire. The creeping barrage was to consist of H.E. and smoke shells and was to move at the rate of 200 metres in six minutes up to the first objective, after this at the rate of 200 metres in eight minutes.

Tanks were to attack in sections of three, two in front and one in immediate support, the infantry advancing in small assaulting groups close behind the tanks.

Directly the orders were issued preparations were set on foot. On July 18, Lieutenant-Colonel H. K. Woods, commanding the 9th Battalion, and his reconnaissance officers visited General de Bourgon,

{30}

the Commander of the 3rd French Division, who explained to them the scheme; on the next day these officers reconnoitred the ground over which the battalion would have to operate, and tactical training was carried out with the French at the 5th Tank Brigade Driving School at Vaux-en-Amienois. On the 20th and 21st training continued, and

further examination of the ground was made, and on the 22nd details of the attack were finally settled. In spite of the continuous exertion of the last few days all ranks were in the greatest heart to show the 3rd French Division what the British Tank Corps could do.

Meanwhile headquarters were selected, communications arranged for, supplies dumped, and reorganisation and rallying-points worked out and fixed.

The move of the 9th Battalion is particularly interesting on account of its rapidity. On July 17 it was in the Bus-les-Artois area; on the 18th it moved 16,000 yards across country and entrained under sealed orders at Rosel, detraining at Conty. On the night of the 19th-20th it moved 4,000 yards from Conty to Bois-de-Quemetot; on 20th-21st, 9,000 yards to Bois-de-Rampont; on 21st-22nd, 7,000 yards to Bois-de-Hure and Bois-du-Fay; and on 22nd-23rd 4,500 yards from these woods into action with thirty-five machines out of the original forty-two fit to fight

.

The country over which the action was to be fought was undulating, and with the exception of large woods there were few tank obstacles. Prior to the operations the weather had been fine, but on the day of the attack heavy rain fell and visibility was poor, a south wind of moderate strength was blowing.

The preliminary bombardment began at 4.30 a.m., and, an hour later, the tanks having been moved up to their starting-points without incident, the attack was launched. The tanks advanced ahead of the infantry, Arrachis wood was cleared and Sauvillers village attacked, the tanks occupying this village some fifteen minutes before the infantry arrived. At Adelpare farm and Les-Trois-Bouqueteaux the enemy’s resistance, as far as the tanks were concerned, was light, and the German machine-gun posts were speedily overrun. From Sauvillers village, at zero plus two hours, the tanks advanced on to Sauvillers wood, which, being too thick to enter, had to be skirted, broadsides being fired into the foliage. Whilst this was

proceeding other tanks moved forward towards the Bois-de-St.-Ribert, but as the infantry patrols did not appear they turned back to regain touch with the French infantry. About 9.30 a.m., whilst cruising round, six tanks were put out of action in rapid succession by direct hits fired from a battery situated to the south of St. Ribert wood. At 9.15 a.m. an attack on Harpon wood was hastily improvised between the O.C. B Company, 9th Battalion, and the commander of one of the battalions of the 51st Regiment. This attack was eminently successful; the French infantry, following the tanks with great élan, established posts in Harpon wood. After this action the tanks rallied.

In this attack the tank casualties were heavy in personnel: 11 officers and men were killed and 43 wounded, and 15 tanks were put out of action by direct hits. The losses in the French Divisions were: 3rd-26 officers and 680 men; 15th-15 officers and 500 men; 152nd-20 officers and 650 men. It should be noted that though the 3rd, with which

tanks co-operated, had to attack the largest system of defences, its casualties approximately equalled those of each of the other divisions.

The number of prisoners captured was 1,858, also 5 guns, 45 trench mortars, and 275 machine guns.

After the attack, when the tanks had returned to their positions of assembly, General Debeney, commanding the First French Army, paid the 9th Battalion the great honour of personally inspecting it on July 25, and of expressing his extreme satisfaction at the way in which the Battalion had fought. As a token of the fast comradeship which had now been established between the French troops of the 3rd Division and the 9th Tank Battalion, this battalion was presented with the badge of the 3rd French Division and ever since this day the men of this unit have worn it on their left arm.