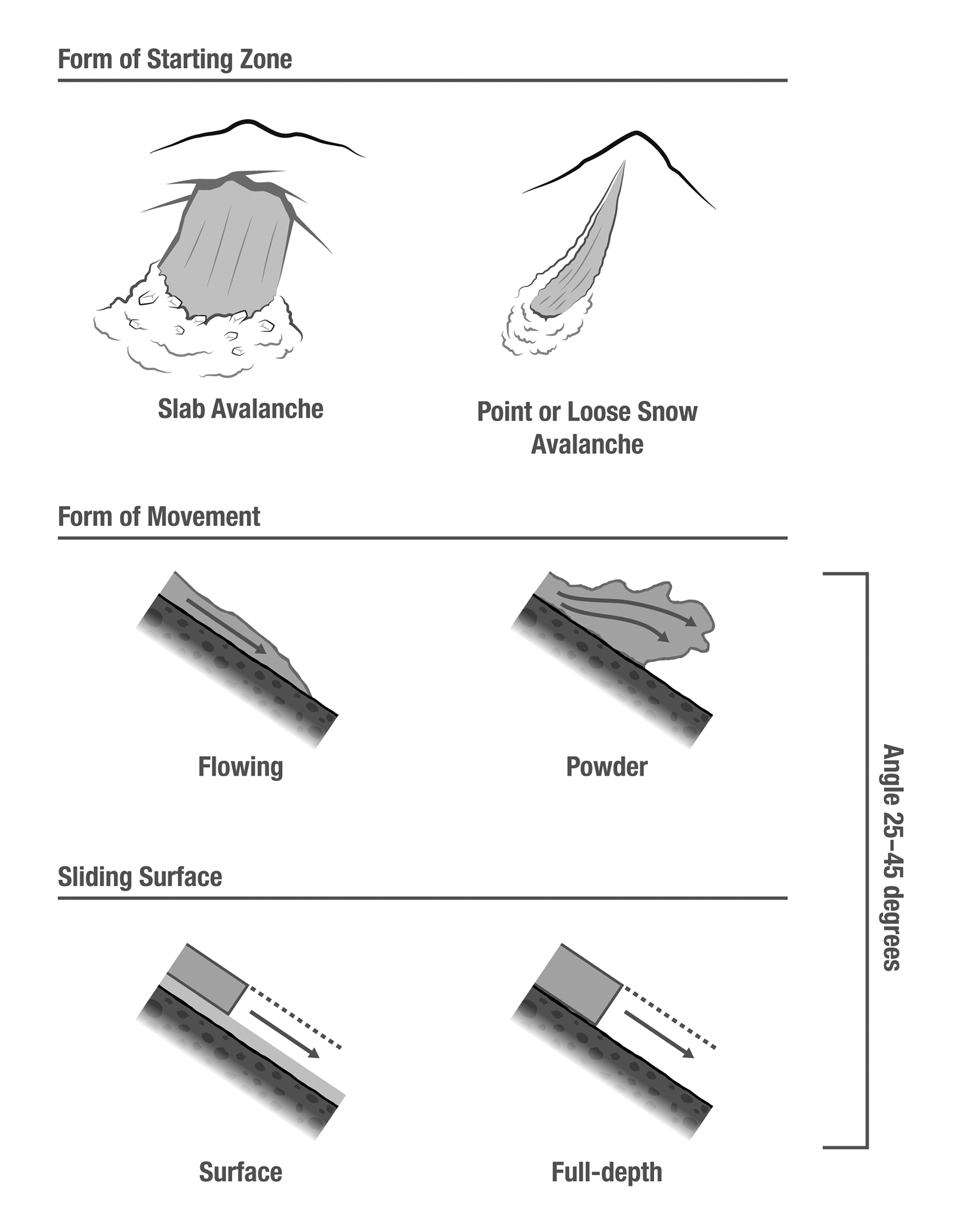

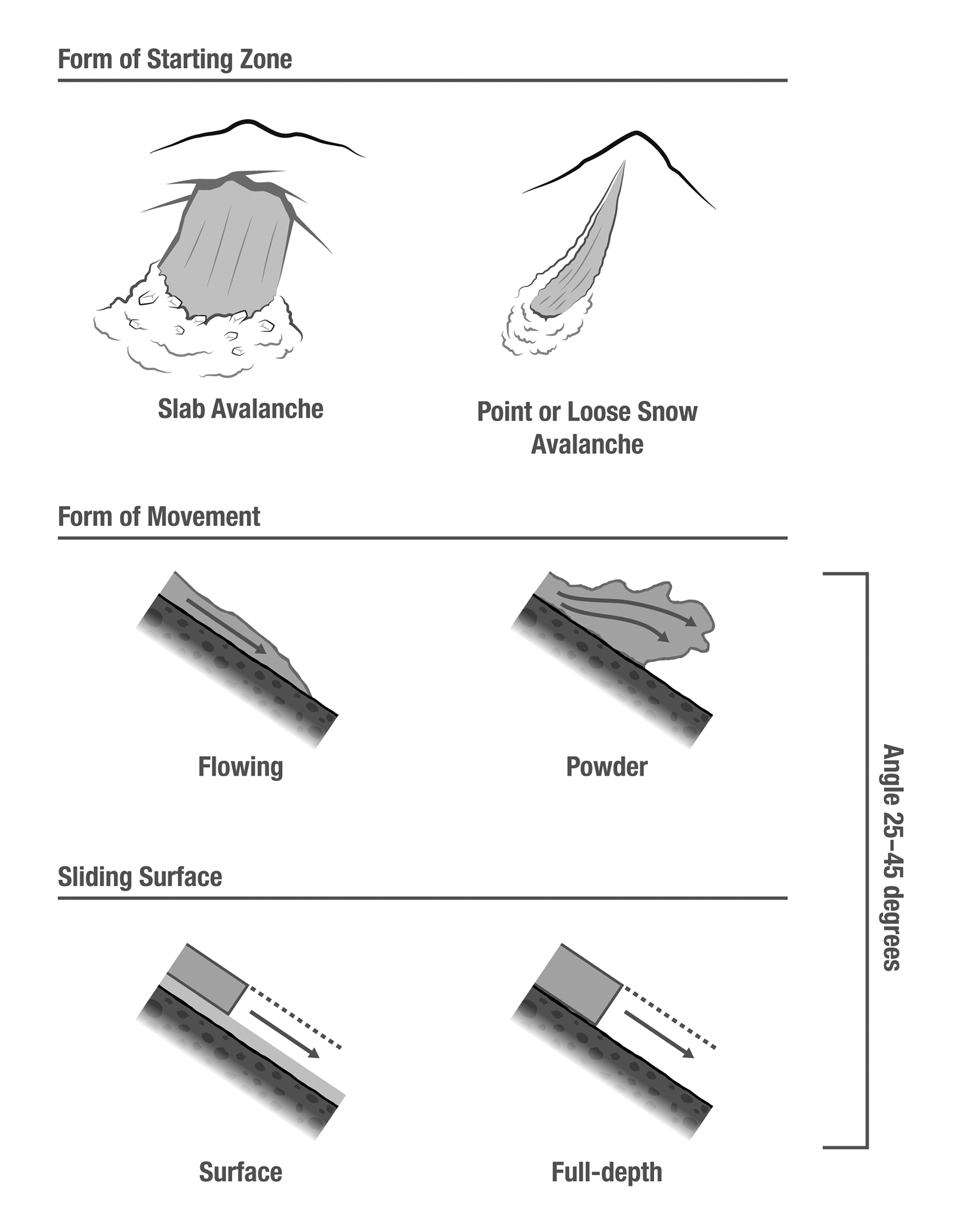

Avalanche awareness and management of risk should begin long before crampons touch the snow, during the preparation phase of pre-trip planning. Understanding the intricacies of weather patterns and the science of avalanches requires coursework and hands-on training. There are a number of organizations that provide this information and education and include regional non-profit groups such as Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC), the Utah Avalanche Center, and Avalanche Canada. The American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education (AIARE) offers advanced training programs to better prepare those entering terrain with avalanche potential. While it is essential that individual climbers obtain such training before entering avalanche terrain, it is equally important that their partners share the same training so they can work together to mitigate risk and make responsible decisions in the mountainous terrain. Basic elements of avalanche formation and action are shown in Figure 17-1. Despite continuing growth in training opportunities, fatality statistics show the need for continued emphasis on avalanche safety (American Avalanche Association 2016). The US national avalanche-related death toll for the 2015–2016 season was 29. Most fatal incidents are triggered by the avalanche victims or someone in their party. Despite common perceptions of this being a problem solely for backcountry skiers, the backcountry lures not only skiers and ski mountaineers, but also snowboarders, climbers, snowshoers, and snowmobilers, who share in its risk. Indeed, snowmobilers now have the highest rate of avalanche-associated mortality (Jekich 2016). The “know-before-you-go” campaign has proven helpful in increasing awareness and training.

Ninety percent of those buried for less than 15 minutes survive. This survival rate drops to a dismal 30% at 35 minutes (Johnson 2015). This would seem to be a reasonable amount of time to find a buried mountaineer, but the actual process of identifying the burial location and retrieving the victim can be lengthy. Burial depth also affects survivability since deeper burial increases extrication time. A one-meter burial requires roughly seven to ten minutes for retrieval. This increases to 15–30 minutes for a two-meter burial (Auerbach 2013). Death typically occurs due to slow asphyxiation, but its causes may also include trauma or hypothermia if enough time elapses. Finally, snow density (increased, for example, in maritime climates) decreases survival either by the difficulty of establishing an adequate air pocket or the challenge of more difficult extrication.

FIGURE 17-1. AVALANCHE CHARACTERISTICS

When traveling in avalanche terrain, one should:

+ Never go alone, since that makes rescue challenging or impossible aside from self-rescue.

+ When crossing an avalanche-prone area of snow, travel one at a time, giving reasonable time for each person to clear before the next one enters it. Consider regrouping in areas of safety protected by natural features.

+ Develop a team travel plan through avalanche terrain, noting sun-exposed or wind-loaded slopes, utilizing safe terrain features, planning escape routes, and avoiding terrain traps such as gulleys and couloirs where burial depth could be concentrated and increased. Start early and leave early to avoid deteriorating snow conditions later in the day (due to temperature changes). Stay away from avalanched areas marked by destroyed vegetation, exposed rock, etc.

+ Teammates should inspect each other for loose items, open jackets, and items that could ensnare avalanche victims. They should also employ a “pre-departure safety check” where search beacons and other avalanche safety equipment are reviewed and found to be functional (read below). Plan ahead to jettison extraneous gear (heavy backpacks and skis), allowing team members to attempt “swimming” if caught in a slide in order to maintain body position close to the rapidly settling snow surface.

+ If a slide occurs, non-buried teammates should search for surface clues and last known position of anyone who is buried.

Each team member should be equipped with the following avalanche safety and rescue equipment: a shovel, a beacon, and a probe. All teammates should learn how to use their beacons and participate in a group beacon check confirming correct mode, battery life, and functioning transmit/receive status. Each team member should be trained and practiced in effective snow probing, utilizing the 3 probe/1 step technique (as described in standard avalanche classes), moving together in an appropriately spaced, efficient, and synchronized team probe line. A probe should remain in place to mark a positive burial finding. Everyone should be trained and practiced in efficient snow removal technique. Teammates should begin shoveling one to one-and-a-half times the suspected burial depth away and downhill from the suspected probe finding. Move snow to the sides when possible, working in tandem as a pair of shovelers or in a team conveyer belt. Practice strategic beacon searching and switching to appropriate beacon mode while searching. Division of responsibilities is important. It should include shovelers, probers, beacon searchers, and a safety supervisor to identify others entering the area, screen for additional avalanche risk, and notify authorities for more assistance. Groups should invest time, training, and equipment in acquiring pre-travel snow analysis with test pits and snowpack evaluation when traveling in avalanche-prone terrain. Individuals and teams should consider whether additional equipment investments in avalanche airbag systems (ABS), Recco reflectors, or Avalung devices are worthwhile for their activity.

Following successful identification and retrieval of the avalanche victim, climbing partners must begin patient assessment. This should not wait for complete removal from the snow burial. The International Commission for Mountain Emergency Medicine (ICAR MEDCOM) has established an evidence-based avalanche management algorithm* for the resuscitation of avalanche burial victims (Brugger 2013). It addresses the initiation and discontinuation of CPR efforts, utilizing findings at the scene (airway status and vital signs) as well as additional clinical information such as ECG (electrocardiogram—measuring electrical activity of the heart) and core temperature when available.

* www.alpine-rescue.org/ikar1-cisa/documents/2013/ikar20131206001112.pdf