14

Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy

Neonatal encephalopathy is a clinical description of generalized disordered neurologic function in the newborn. The most common cause is birth asphyxia. Asphyxia, from the Greek word meaning pulseless, is now used to mean a state in which gas exchange – placental or pulmonary – is compromised or ceases altogether, resulting in cardiorespiratory depression. Hypoxia, hypercarbia and metabolic acidosis follow. Compromised cardiac output diminishes tissue perfusion, causing hypoxic–ischemic injury to the brain and other organs. The origin may be antenatal, during labor and delivery or postnatal (Fig. 14.1).

Fig. 14.1 Antepartum and intrapartum factors preceding neonatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy.

Data from Martinez-Biarge M. et al. Antepartum and intrapartum factors preceding neonatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics 2013; 132; e952–e959.

Other causes of neonatal encephalopathy include transfer of maternal anesthetic agents, cerebral malformations, metabolic disorders (hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia, inborn errors of metabolism), infection (septicemia and meningitis), hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal withdrawal (abstinence) syndrome and intracranial hemorrhage or infarction. The term “birth asphyxia” is best avoided because it is imprecise and implies that the baby’s encephalopathy is a consequence of an asphyxial insult relating to birth, which may have medicolegal implications.

In hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), as opposed to other causes of encephalopathy, there is:

- a significant hypoxic or ischemic event immediately before or during labor or delivery or consistent fetal heart rate monitor pattern

- fetal umbilical artery acidemia (fetal umbilical artery pH < 7.0 or base deficit >/= 12 mmol/L, cord arterial pH < 7.20)

- Apgar score of < 5 at 5 and 10 minutes

- multisystem organ failureneuroimaging evidence of acute brain injury consistent with hypoxia-ischemia.

In developed countries, 0.5–1/1000 liveborn term infants develop HIE and 0.3/1000 have significant neurologic disability. HIE is more common in developing countries.

Pathogenic mechanisms

These include:

- failure of gas exchange across the placenta – excessive or prolonged uterine contractions, placental abruption, ruptured uterus

- interruption of umbilical blood flow – cord compression, cord prolapse, delayed delivery, e.g. shoulder dystocia

- inadequate maternal placental perfusion, maternal hypotension or hypertension – often with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)

- compromised fetus – anemia, IUGR

- failure of cardiorespiratory adaptation at birth – failure to breathe.

Compensatory mechanisms

These include:

- ‘diving reflex’ – redistribution of blood flow to vital organs (brain, heart and adrenals)

- sympathetic drive – increase in catecholamines, cortisol, antidiuretic hormone (ADH, vasopressin)

- utilization of lactate, pyruvate and ketones as an alternative energy source to glucose.

Primary and delayed injury

Following a severe ischemic insult, some brain cells die rapidly (primary cell death due to necrosis) and an excitotoxic cascade is triggered, including release of excitatory amino acids and free radicals. When circulation is re-established, there is a variable time delay before secondary energy failure and delayed cell death due to apoptosis. This offers a potential therapeutic window to ameliorate secondary damage (Fig. 14.2).

Fig. 14.2 Schematic diagram showing potential for prevention of secondary neuronal death.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations, investigations and management are summarized in Fig. 14.3.

Fig. 14.3 Clinical manifestations, investigations and management of hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy. Investigations and management are selected according to clinical features. (NEC – necrotizing enterocolitis; DIC – disseminated intravascular coagulation; EEG – electroencephalogram; aEEG – amplitude-integrated EEG, cerebral function monitor; CTG – cardiotochography.)

Several large multicenter trials have demonstrated the benefit of therapeutic hypothermia in reducing death and disability and increasing survival with normal outcome at 18–24 months. The number needed to treat to prevent one death or disabled infant is seven. Selection criteria for cooling are gestation ≥36 weeks, need for prolonged resuscitation, clinical evidence of moderate or severe encephalopathy and severe metabolic acidosis within the first hour of life. aEEG or EEG are not required to initiate cooling, but may confirm the severity of the encephalopathy and determine if subclinical seizures are present (see Chapter 80). Cooling should be initiated within 6 h of birth. Core temperature is reduced to 33–34 °C and maintained for 72 h before slowly rewarming. Cooling is usually performed in a tertiary NICU but passive cooling (turning off radiant heaters and allowing the baby to lose heat naturally) may be commenced in the delivery room. Adjunct therapies to hypothermia that may further improve outcome are being evaluated, including xenon, melatonin and erythropoietin (see video: Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy).

Clinical staging of hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy

Severity of brain injury can be systematically evaluated using a staging system which is performed sequentially and is of prognostic value. The most common is Sarnat (Table 14.1), although the simpler Thompson score is increasingly used.

Table 14.1 Sarnat staging of hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy.

| Grade 1 (mild) | Grade 2 (moderate) | Grade 3 (severe) | |

| Level of consciousness | Irritable/hyperalert | Lethargy | Coma |

| Muscle tone | Normal or hypertonia | Hypotonia | Flaccid |

| Tendon reflexes | Increased | Increased | Depressed or absent |

| Myoclonus | Present | Present | Absent |

| Seizures | Absent | Frequent | Frequent |

| Complex reflexes | |||

| Suck | Active | Weak | Absent |

| Moro | Exaggerated | Incomplete | Absent |

| Grasp | Normal to exaggerated | Exaggerated | Absent |

| Oculocephalic (doll’s eye) | Normal | Overactive | Reduced or absent |

| Autonomic function | |||

| Pupils | Dilated, reactive | Constricted, reactive | Variable or fixed |

| Respirations | Regular | Periodic | Ataxic, apneic |

| Heart rate | Normal or tachycardia | Bradycardia | Bradycardia |

| EEG | Normal | Low-voltage periodic or paroxysmal | Periodic or isoelectric |

| Prognosis | Good | Variable | High mortality and neurologic disability |

Fig. 14.4 Amplitude-integrated EEG (aEEG) trace from cerebral function monitor showing (a) normal term newborn – normal baseline (>5 μV); (b) severe hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy – low baseline amplitude; (c) seizures in severe hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy unresponsive to phenobarbital but responsive to phenytoin, although the trace remains abnormal.

(Courtesy of Professor Andrew Wilkinson.)

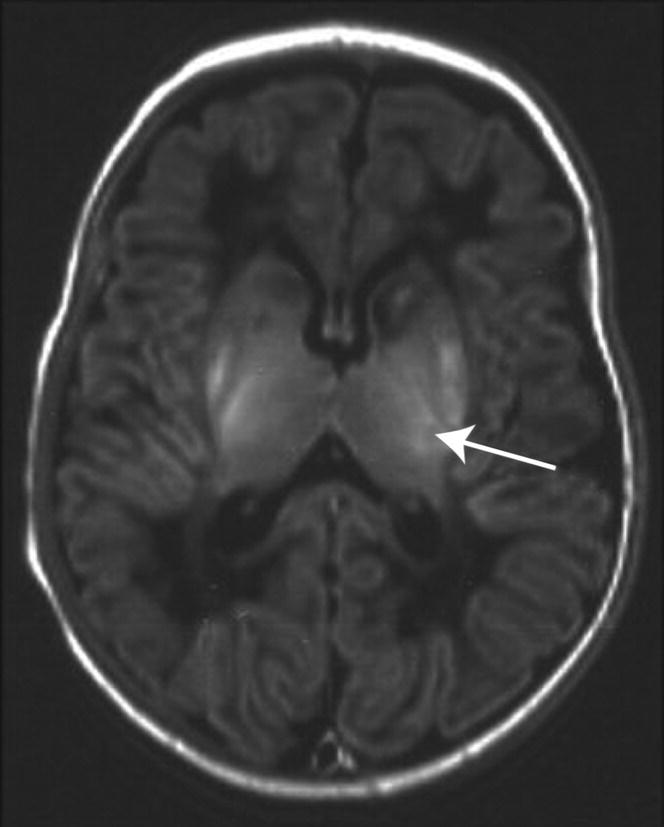

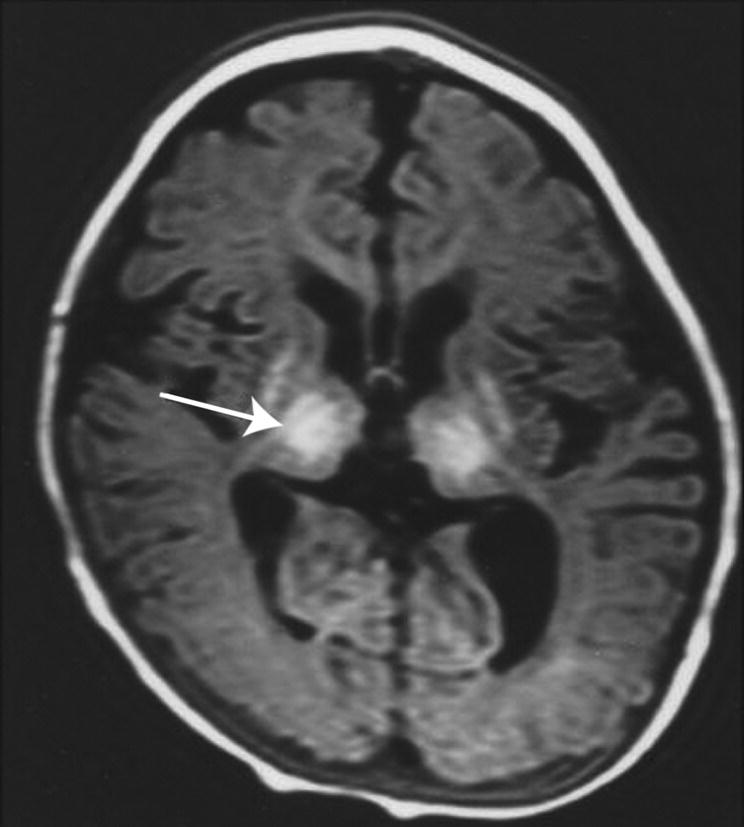

Fig. 14.5 Acute changes typically seen in the first week after perinatal asphyxia on MRI (axial T1W) at the level of the basal ganglia. There is an abnormal high signal in the posterolateral lentiform nuclei and thalami, loss of the normal high signal from myelin in the posterior limb of the internal capsule (arrow), abnormal signal in the head of the caudate nuclei and low signal throughout the white matter.

(Courtesy of Dr Frances Cowan.)

Fig. 14.6 Cerebral atrophy on MRI (axial T1W) developing several weeks after perinatal asphyxia. At the level of the basal ganglia there is severe atrophy of the basal ganglia (arrow), thalami and white matter with enlarged ventricles and extracerebral space. There is also plagiocephaly.

(Courtesy of Dr Frances Cowan.)

Outcome

In general:

- A normal neurologic examination and feeding orally by 2 weeks of age suggest good prognosis.

- Mild HIE – usually good outcome.

- HIE without cooling:

- – moderate HIE – increased risk for motor and cognitive abnormalities, including cerebral palsy (15–20%);

- – severe HIE – 50–75% will either die or have severe disability in childhood (spastic quadriplegia, learning difficulties, visual and hearing impairment, and seizures).

- HIE with cooling:

- – risk of death or disability is reduced by about 60%.

The postnatal markers of poor prognosis are shown in Table 14.3.

Table 14.3 Postnatal markers of poor prognosis.

| Abnormal EEG from birth or aEEG from 6 h with isoelectric pattern or burst suppression in non-cooled infants and later in cooled infants |

| Abnormal MRI (conventional or diffusion-weighted) – particularly basal ganglia/posterior limb of the internal capsule (PLIC) or marked brain atrophy or delayed myelination on later scan |

| Persistence of clinical seizures |

| Persistently abnormal neurologic exam after 1 week (reasonable sensitivity, poor specificity) |

| Not feeding orally by 2 weeks of age |

| Poor postnatal head growth |