37

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) develops in 20−30% of very low birthweight infants and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. The incidence is highest in the extremely preterm (Fig. 37.1); it is uncommon in infants born after 32 weeks’ gestational age.

Fig. 37.1 Incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), at 36 weeks by gestational age at birth in VLBW (very low birthweight infants).

(Vermont − Oxford Network data for 2012.)

Definition

A consensus conference recommended the following definitions:

- oxygen requirement at 28 days of age (used in many trials)

- oxygen requirement and characteristic chest X-ray at 28 days

- oxygen requirement confirmed by physiologic challenge at 36 weeks’ postmenstraual age. This is ascertained by checking if oxygen saturation is maintained in spite of a stepwise reduction in supplemental oxygen until breathing room air. This is the most widely used definition as it identifies infants most likely to have long-term complications.

The conference also recommended that the term ‘bronchopulmonary dysplasia’ be used rather than ‘chronic lung disease’.

Predisposing factors

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia is a multifactorial disorder (Fig. 37.2).

Fig. 37.2 Pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

It most often develops in extremely preterm infants with surfactant deficiency or immature lungs who require mechanical ventilation. Higher pressures (causing barotrauma), excessive tidal volumes (causing volutrauma), high oxygen concentration and longer time on mechanical ventilation all contribute to an increased risk of developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia. However, with current respiratory management of minimal ventilatory support, bronchopulmonary dysplasia is increasingly seen in extremely preterm infants with minimal lung disease during the first few days of life and whose lungs are subjected to minimal barotrauma and volutrauma. Developmental arrest or delay in pulmonary maturation is thought to be primarily responsible (‘new’ BPD), where the histology shows minimal airway lesions, pulmonary edema with little fibrosis but decreased alveolar divisions and vascular development. There may be a genetic predisposition. This contrasts with the postnatal insults causing structural lung injury which were the main causes of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in the past (‘old’ BPD), where there was emphysema and atelectasis, interstitial fibrosis, smooth muscle hyperplasia of the airways and pulmonary vessels and right ventricular hypertrophy.

Clinical features

In addition to the need for oxygen with or without respiratory support:

- skin pallor

- tachypnea

- hyperexpanded chest

- chest retractions

- auscultation – crackles and wheezes

- fluid retention, heart failure

- recurrent pneumonia

- growth failure.

Investigations

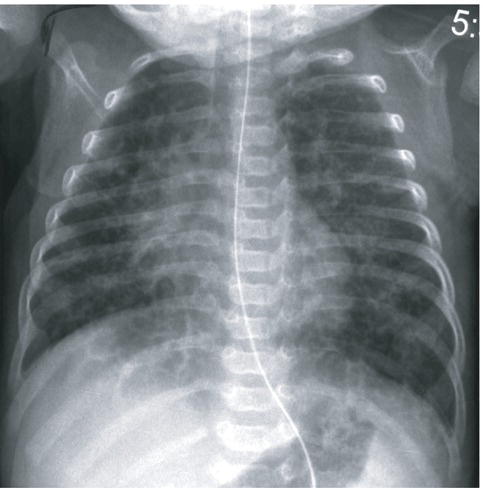

- chest X-ray (Fig. 37.3)

- overnight oxygen saturation monitoring.

Fig. 37.3 Chest X-ray in bronchopulmonary dysplasia showing generalized, patchy opacification of lung fields, lung collapse, cystic changes and overdistension of the lungs.

(Courtesy of Dr Sheila Berlin.)

Management

Management of BPD includes:

- Oxygen and respiratory support (low-flow nasal cannula, high-flow nasal therapy, CPAP or mechanical ventilation) but with oxygenation (SaO2) targeted to 91–95%) (Fig. 37.4).

- Attention to nutritional problems of:

- – increased caloric requirements (130–150 kcal/kg) because of increased work of breathing

- – delay in establishing feeding

- – gastroesophageal reflux (may result in aspiration)

- – prevention of osteopenia of prematurity with phosphate supplements.

- Drug therapy may be considered:

- – inhaled bronchodilators (short-term benefit only)

- – diuretics (transient improvement only)

- – corticosteroid therapy (see below).

- – sildenafil if severe pulmonary hypertension.

Fig. 37.4 Infant with bronchopulmonary dysplasia receiving low-flow nasal oxygen.

Long-term consequences of severe BPD

- Prolonged oxygen therapy and non-invasive or invasive respiratory support may be required for many months. May need to be provided at home.

- Feeding problems requiring prolonged nasogastric/gastrostomy feeding.

- Inguinal hernias (from raised intra-abdominal pressure and muscular weakness associated with suboptimal growth).

- Risk of RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) infection causing bronchiolitis (risk of hospitalization reduced by passive immunization with monoclonal antibody palivizumab).

- Rehospitalization because of respiratory infection.

- Increased risk of asthma and sleep-disordered breathing including obstructive sleep apnea.

- Increased risk of neurodevelopmental problems.

- Rarely, death from acute chest infection or cor pulmonale (pulmonary hypertension).

Strategies for prevention

These include:

- antenatal corticosteroids

- surfactant therapy

- minimizing exposure to mechanical ventilation

- non-invasive respiratory support (CPAP or high flow nasal therapy)

- avoidance of fluid overload

- closure of patent ductus arteriosus

- vitamin A (given in some centers)

- mesenchymal stem cells (via endotracheal tube) – encouraging results in initial therapeutic trials.