62

Hearing and vision

Hearing

Congenital hearing loss affects 1–2/1000 live births. If the infant receives neonatal intensive care, risk is increased 10-fold.

Hearing loss is:

- conductive – involves conduction of sound in the middle or outer ear, often occurs in childhood from secretory otitis media

- sensorineural – involves the hair cells of the cochlea in the inner ear, or the cochlear branch of cranial nerve VIII, as in congenital or neonatal hearing loss.

The speech and language of children with severe hearing impairment are delayed or do not develop. The earlier in life hearing can be restored or specialist assistance provided, the better the outcome. Screening infants with risk factors (Table 62.1) identifies only 40–60% of significant bilateral hearing loss. Universal screening in the first few days of life, and certainly by the age of 3 months is therefore conducted in both the US and UK (Table 62.2).

Table 62.1 Risk factors for hearing loss.

| Family history |

| Syndromes with hearing loss |

| Malformations of the ears, including pits and tags |

| Perinatal |

| Very low birthweight |

| Congenital infection – e.g. CMV (cytomegalovirus), rubella |

| Severe hyperbilirubinemia |

| Ototoxic medications, e.g. furosemide, aminoglycosides |

| Mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy |

| Bacterial meningitis |

Table 62.2 Rationale for universal hearing screening.

| Is hearing impairment common? |

| Yes – more common than hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria or hemoglobinopathy |

| Is the condition serious? |

| Yes. Results in marked speech and language delay |

| Is treatment available? |

| Yes. Sound amplification including hearing aids, cochlea implantation, finger-spelling, lip-reading, use of gestures and sign language to maximize early development of language skills |

| Are reliable screening tests available? |

| Yes. Acceptable sensitivity and specificity |

| Are other methods of detection available? |

| Other methods, e.g. parental concern, are unreliable |

| Does it improve outcome? |

| Yes. The earlier amplification and specialist intervention for infant and family, the better the outcome |

| Offers possibility of preventing progression in certain cases e.g. treatment if caused by congenital CMV |

| Can it be done at reasonable cost? |

| Yes, but requires skilled facilities for diagnostic confirmation and habilitation |

Neonatal hearing screening

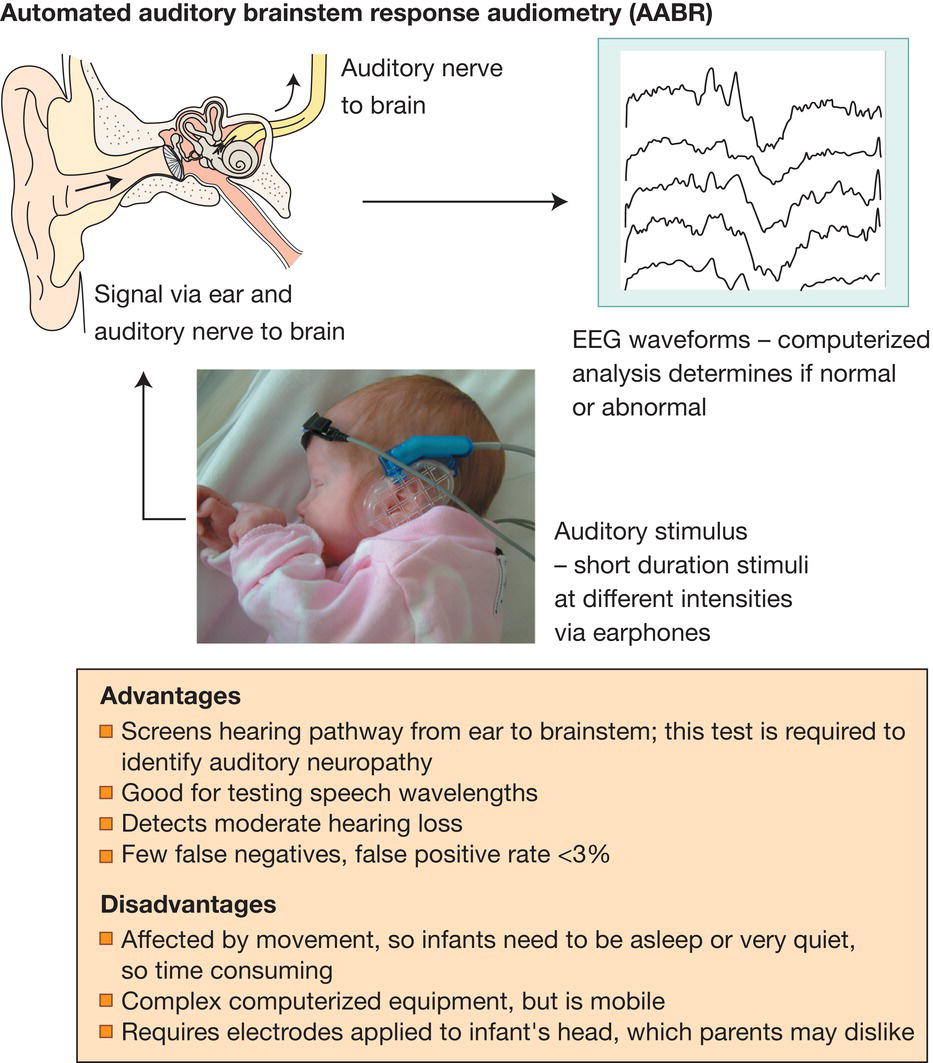

Performed using otoacoustic emissions (OAE) (Fig. 62.1). Repeated if necessary, followed by automated auditory brainstem response (AABR) (Fig. 62.2) if fails OAE. Some centers use AABR as initial test, or for high risk infants.

Fig. 62.1 Otoacoustic emissions (OAE).

Fig. 62.2 Automated auditory brainstem response (AABR).

Vision

The normal term infant will fix and follow horizontally a moving face, a brightly colored object (e.g. a red ball) or a picture of a target of black and white concentric circles by about 6 weeks. They prefer to look at high-contrast patterned objects rather than plain ones.

Visual acuity is initially reduced – only about 6/36. It improves over the first few months, to 6/18 at 4 months and 6/9 at 8 months, but adult visual acuity is not reached until about 3 years. At birth, many have mild hypermetropia (far-sightedness), which persists through early childhood; clarity of vision is achieved by accommodation. This contrasts with preterm infants, who often become myopic (nearsighted).

The eyes of newborn infants are often not aligned, and an intermittent squint (strabismus) is common during the first weeks of life. A constant squint or one persisting beyond 12 weeks post term should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

Lesions needing urgent ophthalmologic referral

During early childhood, failure of focused visual images to reach the retina, e.g. from a cataract or glaucoma, results in permanent loss of vision (amblyopia). Optimal vision is achieved if surgery and optical correction are performed soon after birth (by 6 weeks of age). Affected infants must therefore be referred urgently to an ophthalmologist for surgery.

Cataracts (Fig. 62.3)

Fig. 62.3 Cataract in right eye of a newborn infant.

(Courtesy of Prof. Alistair Fielder.)

Cataracts may be detected by parents or on checking the red reflex with an ophthalmoscope during the routine examination of the newborn, but may otherwise present with blindness at several months of age. Many are genetic, but congenital infection and other causes must be excluded. They are infrequent.

Congenital glaucoma (Fig. 62.4)

Fig. 62.4 Congenital glaucoma of right eye.

(Courtesy of Prof. Alistair Fielder.)

Intraocular pressure is raised. There is watering of the eyes, photophobia and irritability. The eye becomes enlarged and the cornea hazy. Most are bilateral.

Other congenital abnormalities

There are numerous, rare, congenital abnormalities of the eye, including:

- anophthalmos/microphthalmos (absent or extremely small eye)

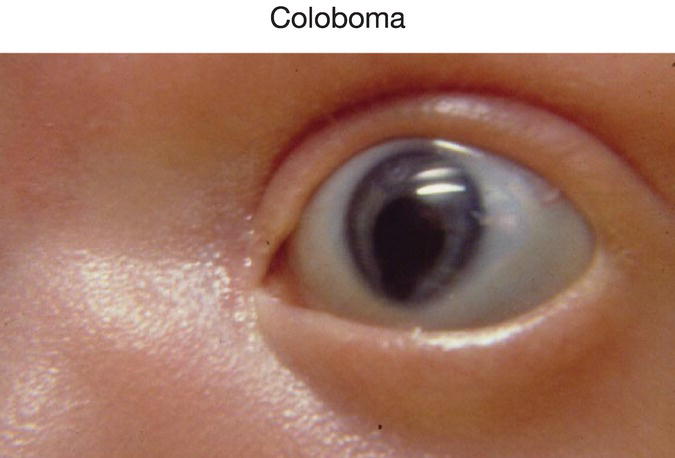

- coloboma (Fig. 62.5) may affect iris, ciliary body, choroid and optic nerve. Vision may be normal in mild cases, but poor if optic nerve involved

- aniridia (absence of iris)

- albinism (lack of melanin pigment in iris and retina) – may be ocular or generalized, often resulting in macular hypoplasia, nystagmus and poor vision

- white pupil (leukocoria) or white reflex on ophthalmoscopy – causes include retinoblastoma, cataract, retinopathy of prematurity.

Fig. 62.5 Iris coloboma. Keyhole-shaped pupil due to defect of the iris inferiorly.

Affected infants should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

The causes of severe visual impairment and blindness in children are listed in Table 62.3. Most visually disabled children also have other disabilities.

Table 62.3 Sites and causes of severe visual impairment and blindness in children (<16 years).

| Whole globe and anterior segment | 7% |

| Glaucoma, cornea, lens (cataract) | 10% |

| Congenital infection | 2% |

| Retina | 29% |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 3% |

| Oculocutaneous albinism | 4% |

| Optic nerve, cerebral/visual pathways | 76% |

In some children there was more than one cause.

Other eye conditions

- Retinopathy of prematurity – see Chapter 35.

- Conjunctivitis – see Chapter 43.

- Chorioretinitis in congenital infection – see Chapter 11.