Hegemony

Richard Day

Like so much in the Western tradition, the concept of “hegemony” originated in Ancient Greece, where the term “hegemonia” was used in a variety of contexts and with various shades of meaning. In one of its common deployments, a “hegemon” denoted a leader or commander, as in the “Catalogue of Ships” recounted in Book II of Homer’s Iliad, which listed the leaders of the formidable Archaean army that sailed on Troy. Featured in this list are many of the great heroes we continue to know today, including Odysseus, Ajax, Achilles, and Menelaus. This historical connection between “hegemony” and “leadership” subsequently becomes codified in the Oxford English Dictionary, which marks “hegemony” as originating during the sixteenth century from the Greek “hegemon” (“leader”) and from “hegeisthai” (“to lead”).

In this usage, hegemony implies consent—or at least acceptance—of the primacy of one individual over others within a community. In such contexts, the concept might best be translated as “leadership.” However, by drawing on Liddell and Scott’s canonical Greek-English Lexicon (1968), which has provided a comprehensive lexicographical overview of Ancient Greek since the nineteenth century, political scientist David Wilkinson has suggested that “hegemonia” often “carried a weightier meaning” (2008, 122). Indeed, “power, leadership, command, supremacy, dominance, dominion, lordship, sovereignty, empire: classical hegemonia sits somewhere in their company” (2008, 124). Consequently, “the entry for hegemonia in the ‘middle Liddell’ [the second condensed version of the lexicon, first published in 1889]” read as follows:

hêgemonia . . . [II.2] the hegemony or sovereignty of one state over a number of subordinates, as of Athens in Attica, Thebes in Boeotia—the hegemony of Greece was wrested from Sparta by Athens; and the Peloponn[esian] war was a struggle for this hegemony. (quoted in Wilkinson 2008, 122)

This is why the Athenians lamented “the Spartan Hegemony” as an exceptional time during which they were governed by someone other than themselves.24 Not another class, or even another nation—Spartans, Thebans, and Macedonians were all Greeks, after all—but a political formation that deprived the governed of meaningful participation in their government. As a mode of political relationship between city-states in Ancient Greece, “hegemony” was very clearly seen as an imposition of rule from outside, achieved and maintained through violence.

According to intellectual historian Perry Anderson, it was the Russian Marxists Georgi Plekhanov and Pavel Axelrod (Anderson 1976a, 16) who introduced discussions of “hegemony” into modern social and political theory near the beginning of the twentieth century.25 The concept was subsequently picked up by Lenin, who argued in 1911 that the proletariat “must be the leader in the struggle of the whole people for a fully democratic revolution. . . . The proletariat is revolutionary only in so far as it is conscious of and gives effect to this idea of the hegemony [gegemoniya] of the proletariat” (1963, 232–33). In the hands of Lenin and his predecessors, “hegemony” shifts away from referring either to individual leaders or to inter–city-state domination. Instead it comes to refer to the leadership of “the whole people” by one group within a national state formation. Moreover, rather than being an external imposition upon an otherwise democratic process within a given political formation, the struggle for hegemony came to be viewed as a normal, internal part of the revolutionary-democratic process itself.26

While the inflexion given to the concept by the Russian Marxists had a lasting impact, Antonio Gramsci’s subsequent elaboration came to dominate the meaning of “hegemony” during the second half of the twentieth century. According to Lenin, revolutions required both violence and hegemony (as leadership) by one class over “the whole people.” This formulation implied that establishing hegemony was not itself a violent process—the violence was in the revolution. In contrast, Gramsci argued that—in the context of struggles within a national-state formation—establishing hegemony necessarily required both democratic consent and violent coercion. By his account, a group seeking “supremacy” must “lead” kindred and allied groups who recognize and accept its moral, intellectual, and political superiority (1971, 57–58). For those who do not display this recognition, however, the hegemonic group must deploy “the apparatus of state coercive power which ‘legally’ enforces discipline on those who do not consent either actively or passively” (1971, 12). In times of “crisis,” Gramsci argued, a group seeking hegemony might even strive to “liquidate” antagonistic groups using armed force (1971, 57). Here the disparate elements, meanings, and contexts of “hegemony” discussed thus far become fused into a self-conscious whole.

At the same time, Gramsci’s theory also brought an important new inflection to the concept. In his view, every human community always already contained a hegemonic force. By this account, even before the Spartans managed to put the Athenians under their thumb, the latter were already being dominated—by themselves. For Gramsci, since hegemony amounted to a pluralized play of antagonistic forces within the boundaries of a nation-state, the natural and inevitable result was that “only one” of the contending forces would “tend to prevail” and “propagate itself throughout society” through control of the state apparatus (1971, 181).

This is the meaning of hegemony that is most common today. It is ascribed to that which is dominant and maintains a relative sway over the thoughts, actions, and habits of everyday people within a given geographic-administrative space. But while it establishes an enveloping narrative with very little in the way of “choice” at any point along the way, “hegemony” itself is not static. Totalizable in the abstract, it always remains partial and relative under concrete circumstances.

Gramsci’s theory of hegemony became the bedrock of Western Marxism—an eclectic grouping of ideas that Anderson (1976b) contended turned away from revolutionary politics to embrace what Lenin would surely have called reformism. In a coterminous move toward reformism, rather than seeking state power in the name of a proletariat-led revolution, twentieth-century social-democratic parties aimed instead to mute capitalism’s worst effects by rewarding workers with decent wages and working conditions. As Anton Pannekoek put it, “the conquest of political power by the proletariat became,” for social-democratic bureaucrats, “the conquest of a parliamentary majority by their Party, that is, the replacement of the ruling politicians and State bureaucracy by themselves” (1927, 4).

The shift away from revolutionary politics during the inter-war period was accompanied by a shift in the understanding of hegemony, which came increasingly to be viewed as “cultural” and “consensual” in nature. This is not to suggest, however, that the theorists of the time entirely forgot the coercive aspect of hegemony as analyzed by Gramsci (the best among them most definitely gave a nod in this direction). It is, rather, a matter of nuance. Beginning with Stuart Hall’s Gramscian reading of hegemonic culture, the following series of moves drawn from media theorist Dick Hebdige’s influential late-twentieth-century analysis of youth subcultures might be taken as exemplary: “The term hegemony refers to a situation in which a provisional alliance of certain social groups can exert ‘total social authority’ over other subordinate groups, not simply by coercion or by the direct imposition of ruling ideas, but by ‘winning and shaping consent so that the power of the dominant classes appears both legitimate and natural’” (Hall 1977, quoted in Hebdige 1993, 366, emphasis added).27

Here the “coercive” moment of hegemony as understood by Gramsci is acknowledged; however, this acknowledgement is simultaneously displaced through Hebdige’s reference to the work of Marx and Engels, in which he writes: “The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas; hence of the relationships which make the one class the ruling class, therefore the ideas of its dominance” (1993, 365, emphasis added). Finally, the displacement of the coercive moment of hegemony is installed directly into Gramsci’s analysis: “This is the basis of Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony which provides the most adequate account of how dominance is sustained in advanced capitalist societies” (Hebdige 1993, 365).

This is the reading of Gramscian theory that came to permeate Cultural Studies, where it intermingled with the burgeoning politics of identity associated with the “new social movement” struggles of the 1960s and 1970s. With the publication of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe’s Hegemony and Socialist Strategy in 1985, the field of action was extended beyond the working class to encompass anyone with a grievance against the existing order. Meanwhile, the physically coercive aspect of the struggle for hegemony disappeared entirely. Instead of seeking to “liquidate” staunch adversaries as Gramsci had proposed, political actors were said to strive for the “articulation” of interests that—though they were conceived into being (i.e., rather than being discovered as preexisting)—could nevertheless serve as points of common identification. In this view, “hegemonic transitions” are “fully dependent on political articulations and not on entities constituted outside the political field—such as ‘class interests’. Indeed, politico-hegemonic articulations retroactively create the interests they claim to represent” (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, xi).

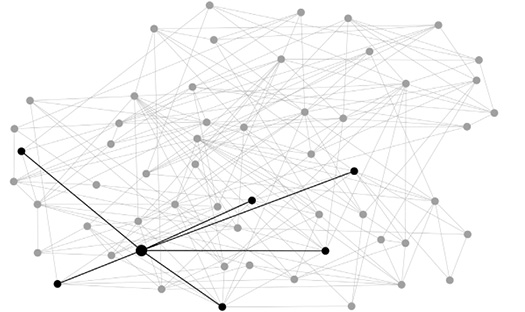

In plainer language, hegemonic articulation refers to a process by which a particular demand can connect with and come to encompass a whole network of related demands, thus universalizing (and hegemonizing) them. The practical ramifications of Laclau and Mouffe’s analysis could be seen in the “movement of movements” that converged to fight corporate globalization at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The more recent Occupy and indignado movements operated according to similar premises.

Laclau and Mouffe’s “hegemony” bears the marks of the Western Marxism and Cultural Studies traditions in that, rather than trying to take state power, the agents of hegemonic articulation are said merely to want to influence its flows. Consequently, many Marxists (e.g., Geras 1987, Bertram 1995) argued that Laclau and Mouffe’s theory abandoned the revolution and wandered sadly into the territory of liberal reformism. This apparent “retreat from class” (Wood 1999) would soon be taken even further. With the concept of “post-hegemony” developed by Scott Lash (2007) and Jon Beasley-Murray (2010), the Western Marxist tradition had been fully deconstructed, with representation and even discourse being supplanted by affective, biopolitical, unconscious actors.

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the theory and practice of non-hegemonic (Day 2005) or prefigurative (Graeber 2004) modes of struggling for social change have gained traction in the radical scene, especially among anarchists and autonomous Marxists. Unlike their counter- or anti-hegemonic counterparts, these struggles focus on the creation of alternative spaces and on living, here and now, the life that one wishes to lead without mediation by the state or other apparatuses of power. With their “one no and many yeses,” the Zapatistas are the iconic movement-image of this approach. Examples of this politics in action also include the land occupations of the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST) in Brazil and the recovered enterprises of Argentina. More broadly, they find symptomatic expression in the negative slogan “Que Se Vayan Todos!” (“They all must go!”), which was advanced in Argentina during the struggles of December 19 and 20, 2001. These struggles culminated in then-president Fernando de la Rúa fleeing the Casa Rosada by helicopter.

Proponents of non-hegemonic modes of social change do not deny the existence of currently hegemonic structures and systems; indeed, they know these exist and are quite wary of their interventions. But rather than trying to take over the structures of power, prefigurative actors seek to render them redundant and ward off their reemergence. It could be argued that these new currents are simply in denial of the fact that they themselves are involved in a struggle for hegemony with the very logic of hegemony itself, and that they are therefore validating the very process they wish to overcome. Similarly, it could be said that those who want to work hegemonically are displaying an autonomous orientation toward those with whom they must articulate to achieve their aims. Considering these possibilities, it becomes clear that hegemony and autonomy are locked in an intimate embrace and that each cannot do without the other. Still, there are rumblings of a new meta-logic, one that treats hegemony and autonomy not as ideological deadweights but as tools to be deployed where they can be most efficacious. “Instead of erecting a wall between horizontalism and hegemonic processes,” writes Yannis Stavrakakis, “wouldn’t it be more productive to study their irreducible interpenetration, the opportunities and the challenges it creates?” (2014, 121). To this I can only respond: yes, indeed, I think it would.

See also: Authority; Domination; Intellectual; Leadership; Prefiguration; Sovereignty

24. Of course, when it was the Athenians who had the upper hand, they assumed this was because of their excellent leadership qualities. For example, Aristotle saw armed force as being justified in securing hegemony in foreign affairs if one was not acting despotically, but “for the benefit of those who are ruled” (quoted in Keyt 1993, 144).

25. David Wilkinson (2008, 120), however, presents quite convincing evidence that scholars such as J. C. F. Manso (writing on the Spartan Hegemonie in German) and Groen van Prinsterer (on the Athenian hegemonia) were using the term in a similar way to the Russians, in the early nineteenth century.

26. This is not to say that Lenin denied the necessity of a violent component in what he called the Social Democratic revolution. In his discussion of the notion of the “withering away” of the state, he argues very clearly that, for Marx and Engels, “[t]he supersession of the bourgeois state by the proletarian state is impossible without a violent revolution” (1964a, 405).

27. Hebdige here cites Stuart Hall, who was to a great extent responsible for the resurgence of interest in the concept of hegemony in the 1980s. It is important to acknowledge that Hall was always aware of the dual nature of Gramsci’s concept, which involved both coercion and consent. It is also important to acknowledge that the move made by most practitioners of Cultural Studies (the move toward a “merely cultural” understanding of hegemony), was often made, as I have shown with the example from the work of Dick Hebdige, through a reliance on Hall’s work.