Occupation

Sara Matthews

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “occupation” can be traced back to the twelfth-century Anglo-Norman and Old French “occupacion” and first appeared in English as a noun denoting employable activity. During the thirteenth century, it came into usage as a verb denoting the action of taking possession of land or space, as in a tenancy or holding. As contemporary debates concerning the concept’s usefulness for social and political struggle make clear, “occupation” has the power to expose and reconcile but also to repeat the traumatic legacies of our colonial past and present.

In its widest sense, “occupation” is a dynamic of power and spatiality. According to the OED, “occupation” corresponds to “the action of taking or maintaining possession or control of a country, building or land, especially by military force; an instance of this or period of such action; the state of being subject to such an action.” Key to this formulation is the slippage between “occupation” as an action and as a subjective experience. For radicals, the hope is that the subjective experience and objective dynamics of occupation by hostile powers might be exposed and then transformed by means of radical occupations carried out by the people themselves. For contemporary radicals, perhaps one of the most familiar instances of this kind was the Occupy Wall Street movement. Before considering the veracity of occupation as a practice of resistance, however, it is important to consider its historical legacy as an instrument of state building.

Often a mechanism of state violence, occupation signals the installation of a sovereign presence through organized campaigns that aim to subjugate the target group physically, socially, and psychically. The first recognized iteration of occupation as a military tactic was coded into international law via the United Nations 1907 Hague Convention resolution concerning “Laws and Customs of War on Land.” Considered a temporary rather than permanent solution to conflict, military occupations have nevertheless tended to strip citizens of their sovereign rights and expose them to political and social exploitation. Given that the United Nations endorses the Westphalian system—which presupposes the territorial integrity of sovereign nations—occupation has become an important problem of geopolitics and international law.

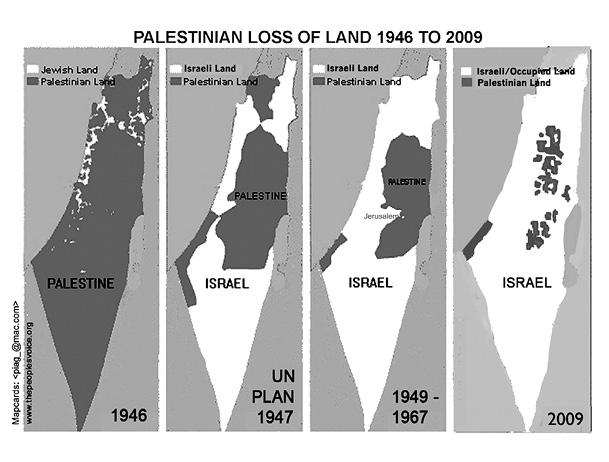

The phrase “territories occupied” first appeared in United Nations Resolution 242, which called for “withdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied” during the Six-Day War. Nevertheless, the longest-standing military occupation in contemporary times remains the Israeli occupation of Gaza, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and East Jerusalem. Since 1967, Israel has unilaterally occupied Palestinian territory and systematically denied Palestinian residents their right to return to confiscated lands, to access the economic and physical resources necessary for survival, and freedom of movement and self-determination.

Cartographies of the region produced over the past forty years reflect these geopolitics. Maps that label the area “Palestine” rather than “Occupied Territories,” for instance, suggest a resistant sovereignty that refuses ongoing Israeli occupation. Indeed, the iconic “disappearing map” of Palestine used by groups like the Toronto-based Queers Against Israeli Apartheid has become an important pedagogical tool in campaigns aimed at revealing the geography of occupation. The disappearing map exemplifies the ambivalent nature of occupation (see Figure I): it announces Palestinian resistance at the same time as declaring the colonizing threat of the Israeli intervention.

Figure I

References to Israeli “occupation” have also appeared more broadly in discourses concerning human rights abuses. For instance, Amnesty International’s “Enduring Occupation” report (2007) details the subjective experience of life under occupation, including the impacts of the illegal apartheid wall, the unlawful procurement of lands and natural resources, the destruction of Palestinian homes and olive groves, and growing restrictions on physical movement. Although Israel officially disengaged from Gaza in 2005 and declared itself no longer to be an occupying force, it has continued to retain control of Gaza’s airspace and coastline, effectively sustaining sovereign pressure through military occupation of the air and sea.

In addition to being a tool of belligerent nation-states, however, occupation has also historically been a tool of opposition and resistance. This approach involves attempts to reconfigure the spatial formations that uphold repressive regimes. In opposition to spatial restrictions, radical acts of occupation contest restrictions on psychic and physical survival through efforts to reassert claims on public space. In the context of the Israeli occupation of Palestine, groups like the International Solidarity Movement (ISM), formed in 2001, act in solidarity with those forced to confront the experience of occupation. With their campaign to “End the Occupation,” ISM has made use of nonviolent and direct-action tactics including accompaniment, physical removal of IDF roadblocks, organized violation of curfew orders, blocking tanks and bulldozers, and interference with the Apartheid Wall through political graffiti. While such tactics disrupt the mechanisms of Israeli occupation, they also provide opportunities for Palestinians and their international allies to reclaim or reoccupy public space as a political act of resistance. The Electronic Intifada provides a further example of how the tactic of occupation might be reconfigured for emancipatory ends. Started in 2001 by writers and reporters from Palestine and beyond, the publication challenges occupation by providing an alternative space for digital information and popular education.

These strategies intend a reconfiguration of the act of possession upon which military occupations rely. However, they also demonstrate how occupation itself can be galvanized as resistance. Arising from political struggles in Palestine and elsewhere, the demand to “end the occupation” stands at odds with the concurrent injunction to “occupy everything” advanced by those for whom “occupation” is first and foremost a strategy of resistance. Bady and Konczal (2012) trace the slogan “Occupy Everything, Demand Nothing” to the California student movement of 2009, in which students protested the neoliberalization of the university—as well as their experience of scholastic alienation—by occupying campus buildings.

As a form of public dissent and protest, occupation has a long history in social movements. In “Tactic: Occupation,” Russell and Gupta (2015) describe occupation as a method “to hold public space; to pressure a target; to reclaim or squat property; to defend against ‘development’ and to assert Indigenous sovereignty.” In this context, they highlight the example of the labor strike. By mobilizing labor (i.e., practical human activity) against its everyday “occupation” within capitalism, a strike can seize hold of the workplace and interrupt the relations that alienate workers from their own subjectivity. Normally cast as what Marx in The Communist Manifesto (1848) called “an appendage of the machine,” striking workers marshal their “occupation,” which has value on the market, against their own alienation. Russell and Gupta provide the following short history of actions that have resisted labor as capitalist occupation:

In seventeenth-century England . . . the Diggers formed a utopian agrarian community on common land. Workers, soldiers and citizens established the Paris Commune in 1871. In the United States, in the Great Upheaval of 1877, striking railway workers and their supporters occupied train yards across the land. A wave of plant occupations in the mid-1930s led to the justly famous Flint sit-down strikes of 1936, which won union recognition for hundreds of thousands of auto workers. (2015)

Seizing public space or repurposing privatized space in this way distinguishes radical occupations from those that are sanctioned by—and reproduce—normative standards of sovereign power. As an oppositional act, occupation seeks to expose and unsettle the boundaries maintained by sovereign rule. According to London-based writer and activist Anindya Bhattacharyya (2012), “We live our lives surrounded by a field of invisible regulations that tell us where we can or must go, and what we are and aren’t allowed to do there. Occupation makes these regulations of bodies in space visible.”

As a radical practice, occupation refuses the enclosure of what would otherwise be common and challenges sovereign power’s partitioning of space in the interest of mastery and knowability. For Michel Foucault, such regulated “disciplinary space” aims to “establish presences and absences, to know where and how to locate individuals, to set up useful communications, to interrupt others, to be able at each moment to supervise the conduct of each individual, to assess it, to judge it, to calculate its qualities or merits” (1975, 143).36 If, as a dimension of sovereign rule, “occupation” is also a project of what Foucault called “power/knowledge,” then “occupation” as a radical tactic creates new opportunities for self-knowledge and self-determination while challenging disciplinary regimes. Consider, for instance, Hakim Bey’s (1991) Temporary Autonomous Zone, which he viewed as a moment of festive non-hierarchical gathering that could foster collective conviviality in the face of state control.

The TAZ is like an uprising which does not engage directly with the State, a guerilla operation which liberates an area (of land, of time, of imagination) and then dissolves itself to re-form elsewhere/elsewhen, before the State can crush it. Because the State is concerned primarily with Simulation rather than substance, the TAZ can “occupy” these areas clandestinely and carry on its festal purposes for quite a while in relative peace.

By this account, the TAZ provokes momentary utopias that challenge the normative order and transcend the ordinary by creating subjective experiences of convivial intensity. Out of these moments, difference can be imagined and then made. Other forms of collaborative resistance to enclosure that claim space for the expression of alternative visions include Reclaim the Streets and Critical Mass, both of which have mobilized occupation as a physical and psychic strategy.

Reclaim the Streets is a direct action network with roots in the United Kingdom whose tactics of creative festivity have spread to cities around the world. Calling for the creation of “collective daydreams” that challenge normative life under capital, Reclaim the Streets argues that “ultimately it is in the streets that power must be dissolved: for the streets where daily life is endured, suffered and eroded, and where power is confronted and fought, must be turned into domain where daily life is enjoyed, created and nourished.” Writing in the Guardian, journalist Jay Griffiths (1996) described the seven-thousand-strong occupation by Reclaim the Streets of the M41 in West London as a carnival aimed at reclaiming the urban commons from car culture. For its part, the Earth First!-inspired periodical Do Or Die summed up movement sensibilities when it recounted how Reclaim the Streets was “not going to demand anything. . . . We are going to occupy” (“Reclaim the Streets” 1997). Formed in San Francisco during the early 1990s and now used in different cities around the world, Critical Mass similarly reclaims urban space by using bicycles to occupy roadways that predominantly serve cars.

An understanding of this approach would be incomplete, however, without a discussion of Occupy Wall Street. Prompted by Micah White’s July 2011 call for “a worldwide shift in revolutionary tactics” published in Adbusters, the movement revitalized interest in occupation’s meaning and possibilities. “What makes this novel tactic exciting,” White wrote, was “its pragmatic simplicity”:

We talk to each other in various physical gatherings and virtual people’s assemblies . . . we zero in on what our one demand will be, a demand that awakens the imagination and, if achieved, would propel us toward the radical democracy of the future . . . and then we go out and seize a square of singular symbolic significance and put our asses on the line to make it happen.

Approximately one thousand people coalesced in Manhattan’s Financial District on September 17, 2011 in response to White’s call for people to occupy Wall Street, which he identified as the “financial Gomorrah of America” (White 2011). Many stayed on to establish a tent city in Zuccotti Park, which they occupied for about two months. Occupy Wall Street inspired hundreds of similar actions in cities around the world. In his brief history of the movement, Willie Osterweil (2011) notes how the activists in Lower Manhattan borrowed a page from sources as varied as the Indignado Movement in Spain, the Egyptian revolution, and struggles for workers’ and veterans’ rights in the United States. The power of occupation, Osterweil writes, is that “it foregrounds the political issues of everyday life and public space, it produces a positive communitarian solution to the problems it critiques, it is highly visible and struggle is continuous in a way that radicalizes its participants” (2011).

However, given occupation’s legacy as a practice of sovereign rule imposed from without, it is not surprising that the movement’s use of the term and tactic prompted criticism. What are the ethics and politics of occupation as radical practice when the concept remains closely bound to colonial and settler relations? Activist Harsha Walia (2014) raised this dilemma when she noted how “one of our most common rally slogans” remains “from Turtle Island to Palestine, occupation is a crime.” Matt Mulberry (2014) considered the problem from a slightly different angle when he asked whether the term “occupation delegitimize[s] movements by casting participants as short-term guests, instead of representatives communicating grievances held by a wider society within a public forum that is theirs?” Whatever the case, “occupation” as an exercise in creative resistance remains haunted by the term’s concurrent history as an oppressive force. We must therefore recognize its limits as well as its possibilities.

See also: Colonialism; Nation; Sovereignty; Space; War; Zionism

36. Indeed, the various meanings of “occupation” recounted above are each given practical expression in Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. (i) As knowability: “to each bed was attached the name of its occupant” (1975, 144). (ii) As territorial encroachment: “the Chassaud ironworks occupied almost the whole of the Médine Peninsula (1975, 142). (iii) As form of labor and as psychic imposition: “there was compulsory work in workshops; the prisoners were kept constantly occupied” (1975, 122).