Rights

Rebecca Schein

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “right” derives from the Indo-European root “reg-,” which referred to “movement in a straight line.” It entered Old English in the eighth century as “reht” or “riht” (by way of the Proto-Germanic “rekhtaz”), denoting “fairness, justice, just claim.” In the ninth century, “reht” generated the verb “rihtan,” meaning “to straighten, rule, set up, set right,” which evolved during the twelfth century into “rigten,” “to correct, amend.” During the thirteenth century, it emerged as a noun, a “legal entitlement or justifiable claim (on legal or moral grounds),” and corresponded closely to its concurrent adjectival form, “that which is considered proper, correct or consonant with justice.”43 Despite several transformations in the interim, this Middle English usage is largely consistent with the contemporary one.

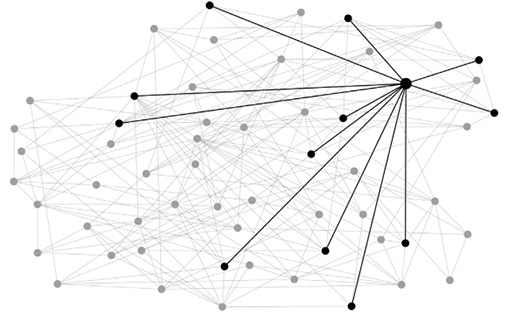

With the emergence of right as “a moral quality, annexed to the person” came the establishment of our modern notion of “rights,” both as intrinsic properties of individuals as such, and as an effect of a recognized relationship of moral obligation with others in a community. (Grotius 2001, 49). “Rights” are always signals of relationships, yet—especially in the case of “human” or “natural rights”—they often leave that relationship unnamed (or name only a relationship to god), as if the act of naming would undo the speech act carried out in the declaration of rights: namely, that they reside inalienably in individuals as such, and that their existence necessarily precedes the human acts of recognition through which we acknowledge their self-evident truth.

This conceptual tension has been a preoccupation for theorists on both the Left and the Right.44 Edmund Burke famously declared that he would rather have the rights of an Englishman than a man, as only the relationship called “Englishness” could transform abstract “man” into a recognized citizen of a particular political community (2001). In her analysis of the “perplexities of the right of man,” Hannah Arendt came to a similar conclusion: since all rights are effectively citizens’ rights, the only meaningful “human right” is the right to be a citizen somewhere (1951, 290). In On the Jewish Question, Marx zeroed in on the relationship between the civil and political emancipation of the Jews and liberalism’s impoverished vision of freedom, which rested on the “decomposition of man” into “Jew and citizen,” “individual life,” and “species-life”—a half-hearted vision that mistook the “rights of egoistic man, of man separated from other men and from the community” for “humanly emancipation” (1978, 40).

For Marx, “the rights of man” signaled the disavowal of the social relations he considered to be the substance of humanity. Echoes of his skepticism still resound in contemporary radical circles despite the “rise and rise of human rights” as the framework for moral claims (Sellars 2002). One effect of that rise has been the increasing significance of law as a site for the realization of justice projects. Whether rights are being recognized or denied, proclaimed or violated, the idiom invokes legal experts and individual claimants as protagonists while the courtroom and legislature become scenes of defeat, compromise, or victory. While savvy participants in such battles may recognize a legal strategy’s interdependence with popular struggle, the turn to “rights” nonetheless orients struggle toward the law and its experts. Although natural rights may be proclaimed in the streets, the pursuit of “rights” seems to end in the courts—the domain not of “the people” but of a lawyerly priesthood (Kennedy 2005). Legislative wins and legal precedents may signal substantive changes in the organization of social life. However, as David Rieff has observed, too often we mistake the advancement of human rights law for the advancement of human rights as such (2002). Meanwhile, as Marx observed, in the contest “between right and right, force decides,” and “force” is not simply a matter for the courts (1976).

The ethical entanglements that give “rights” their social purchase are also their undoing—at least when it comes to human or natural rights, “the rights of man” rather than the “rights of citizens.” The power of such rights stems from their putatively pre-political, trans-historical status, which enables those invoking them to question the legitimacy of particular laws in particular times and places. However, these pre-political, trans-historical rights are also predicated on a putatively trans-historical, pre-political human subject, which—for most of its history—has been the exclusive property of a small stratum of white men. But even when our declarations affirm the natural rights of all humans, irrespective of nationality, race, or other differences, the implicit attachment to a pre-political subjectivity remains a persistent point of tension between rights’ moral power and their social effects. This tension raises a number of troubling questions.

First, what is the nature of this trans-historical subject as it has grown to include a wider swath of humanity? Genocide, slavery, expropriation: the costs of exclusion from the category “human” are well known. But are there costs associated with inclusion? According to Angela Davis, Frederick Douglass witnessed American chattel slavery transmute into the convict lease system; however, he was unable to identify their similarity, focused as he was on the recognition of former slaves as subjects of law whose freedom would be realized through the recognition of political rights (Davis 1998). Similarly, in the Seneca Falls Declaration, Elizabeth Cady Stanton made the case for women’s inclusion among “the people” (the signatories of the Declaration of Independence), identifying women’s exclusion as the substance of their grievance (1995). Both Douglass and Stanton leave unchallenged the character of rights’ subject, asserting only the need to include more kinds of people within its reach. In these instances, rights claims yield a particular understanding of the nature of oppression, and thus a particular—arguably narrow—understanding of what it would mean to reverse it.

The putatively pre-political character of the rights-bearing subject also raises serious questions. Naming “biological humans” as its natural subjects, human rights sets the gears of procedural justice in motion and provides the foundation for all other rights. This is a substantial feature of human rights’ power as an aspirational moral language, particularly for those in the process of demanding recognition. The ideal of pre-political rights usefully empowers individuals to make certain basic claims (e.g., “I am human”), which ostensibly insert them into the web of law and ethics. Such an account, however, represents an optimistic fantasy and presumes that the perfect execution of law represents the substance of justice itself.

For Wendy Brown, this fantasy is a symptom of human rights’ anti-political character (2004). Do human rights help to provide the ethical grounding for collective deliberation, as Michael Ignatieff (2001) argues, or do they function instead as moral “trump cards” that shut down dialogue and shrink the ground of political negotiation? To what extent do human rights presume the substance of justice, generating consensus about its meaning only by taking it off the deliberation table? What use, then, would human rights have for radicals? Must we grapple with the power of rights only as a defensive response to their status as moral claim-making’s hegemonic idiom (perhaps reason enough), or do rights also have something to offer us in our efforts to build meaningful equality, solidarity, or community?

Hannah Arendt famously refuted one of the most sacred principles of human rights in her attempt to divine their real social foundation. “We are not born equal,” she wrote. “We become equal as members of a group on the strength of our decision to guarantee ourselves mutually equal rights” (1951, 301). This human rights heresy provides a useful foundation for a radical engagement with the rights tradition. Arendt concludes that “there is only one human right,” the “right to have rights”—the right, in other words, to be recognized as a member of a political community, the parameters of which are not natural or god-given but the result of human deliberation. Although Arendt does not provide an escape hatch from what she identified as the paradox of human and citizens’ rights, she helpfully locates the rights project at the point where radical political projects must begin and end—namely, by asking questions: Who counts as a subject of justice? (Fraser 2010). How are the parameters of membership morally justified? How will we (re)organize ourselves to ensure one another equality, and what form will that equality take? What, in other words, does our vision of a just society look like?

Whatever ambivalence radicals may feel about framing our claims within a rights framework, there are times when human rights inarguably serve as an important tool in our defensive arsenal. For instance, only the UN Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness served as a check on the ambitions of Canada’s Conservative government, which introduced legislation in 2015 to strip dual citizens of their Canadian status when convicted of terrorism-related offenses. But can “rights” serve a more ambitious, politically radical vision? Two recent mobilizations of rights represent divergent attempts to repurpose rights language for justice projects radically at odds with the rights regime undergirding capitalist liberal democracies. In Aboriginal Rights Are Not Human Rights, Peter Kulchyski (2013, 37) describes what he sees as a “conceptual confusion between human rights and aboriginal rights,” a confusion evident not only among indigenous activists wary of any kind of rights language, but also in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. For Kulchyski, aboriginal rights are not a special variety of human rights but a class of rights apart, invoking a moral logic that diverges from—and even conflicts with—the universalist individualism of the human rights tradition.

Although Kulchyski’s language mirrors earlier claims that, for example, “human rights have not been women’s rights,” critics of the exclusion of women from human rights frameworks sought recognition of women as “representative humans,” whose violation would constitute a violation of humanity as such (MacKinnon 2001, 526). In contrast, Kulchyski calls for the recognition of two distinct rights for indigenous peoples: their human rights and their indigenous peoples’ rights. In a context where human rights have often been used to undermine indigenous rights, Kulchyski argues, the instances of legal and social recognition for indigenous rights—in both national and international foundational documents, however jumbled—can be wielded to advance indigenous peoples’ collective rights to preserve distinct cultures and modes of production. We should not accept, Kulchyski urges, the subordination of indigenous rights to human rights, especially given the way universalist claims have justified the violation of both kinds of rights for indigenous people in Canada and elsewhere. Nor should indigenous organizations and activists abandon as dead letters the rights set out in the Canadian constitution and in the UNDRIP. When Marx wrote that “between right and right, force decides,” he invoked the conflict between workers and capitalists, each as property owners demanding the “full value” of their property. The substance of that force, of course, was class struggle. Between human and indigenous peoples’ rights, Kulchyski suggests, what might emerge are alternative “principles of social justice and democracy” that arise by “plac[ing] special value on meaningful difference” (MacKinnon 2001, 169).

Where Kulchyski distinguishes indigenous rights from human rights to distinguish the former from a liberal individualist heritage, David Harvey and other proponents of the “right to the city” opt rather to reclaim as “human” a right that is intrinsically collective and materialist. Not simply a right to access urban resources, Harvey presents the right to the city as “the right to change ourselves by changing the city more after our heart’s desire”—a right, in other words, to remake the “humanity” that is the subject of human rights (2003, 939, 941). The right to the city has emerged as an organizing umbrella for a diverse array of urban struggles around the world. In contrast to the defensive, even minimalist political vision of conventional human rights, the right to the city offers an ambitious vision of humanity’s collective capacity to transform itself by transforming the social world.

Many conventionally recognized rights claims can be made within the rubric of the right to the city. However, the right to the city locates rights through the simple but profound observation that rights cannot be exercised unless they literally take place. Jeremy Waldron makes this case when discussing the impact of privatization on the rights of homeless people simply to exist (1991). The evisceration of public space by property, Waldron observes, has a cataclysmic effect on people whose most basic human right—their right to be—is contingent on their right to be somewhere. Just as the division of the world into states means that statelessness is tantamount to rightlessness, the total division of the world into private property makes property the sine qua non of all other rights.

Right-to-the-city advocates foreground the material and relational substance of rights; the “who” and the “where” become the subjects of deliberation. Rights, they argue, are for the city’s inhabitants rather than for its property owners. But who counts as an inhabitant? What are the spatial and temporal boundaries of membership, and what shared institutions are empowered to recognize or arbitrate membership? Finally, how will the city—and, by extension, its people—be created and re-created? These are the questions that go unasked when we focus on human rights, their answers presumed in the pre-political “human” that is the subject of rights. Although “the city” appears as its object, “the relation” (the “smallest unit of analysis”) is the open question at the heart of the right to the city. It is also the invitation for radical political visioning.

See also: Accessible; Authority; Crip; Demand; Democracy; Labor; Liberal; Oppression; Privilege; Queer; Responsibility; Trans*/-