CHAPTER 3

PREPARING FOR BATTLE

“It is a doctrine of war not to assume the enemy will not come but rather to rely on one’s readiness to meet him.”

— Sun Tzu

“Habit gives strength to the body in great exertion, to the mind in great danger, to the judgment against first impressions.

— Carl von Clausewitz

Sun Tzu underscored the importance of knowing your enemy and yourself in order to create a tactical advantage in battle. A defined combat plan raises morale by decreasing the element of surprise. It thus behooves the martial artist to define the challenge and study the opponent’s strategy and fighting habits prior to an upcoming competition. Granted, a surprise attack on the street, or a true tournament where you will be fighting several opponents until the last man is standing, makes it difficult to apply this concept. Yet proper preparation through disciplined drill will raise your courage and turn the odds in your favor. As acknowledged by Tsutomu Ohshima, founder of the Shotokan Karate of America Organization, no amount of encouraging words, only consistent training, can give the fighter the mental fortitude he needs to meet an enemy in a struggle of life and death.1

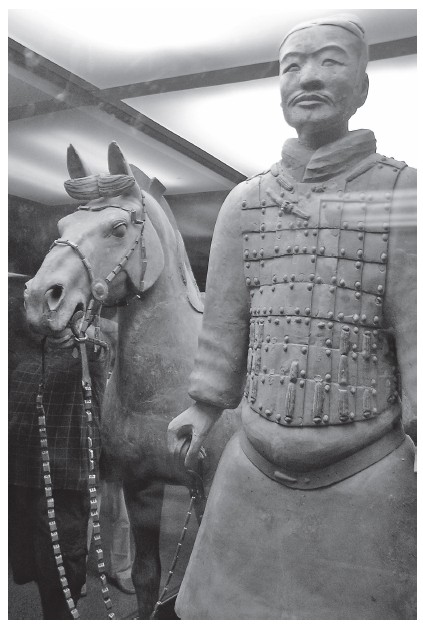

Ch'i, described by Sun Tzu as the will and intention to enter battle, is attained by defining the objective, assessing the situation, and physically preparing for the engagement. Organizing military campaigns through this sequence of events translates into clarity of vision. Coupled with skill and accuracy, it leads to confidence and fighting spirit.2 The Terra Cotta army, comprised of thousands of life-size clay figures guarding the tomb of the First Emperor of Qin who died in 210 BCE, demonstrates the importance one placed on military preparedness in ancient China. As reinforced nearly two thousand years later by Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799 CE) of the Qing Dynasty, whose long lasting reign resulted in great expansions of China’s boundaries, “Indeed, soldiers may not be mobilized for one hundred years, but they may not be left unprepared for one day.”3

Terra Cotta soldier and horse. The thousands of life-size clay figures guarding the tomb of the First Emperor of Qin demonstrate the importance one placed on military preparedness in China. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

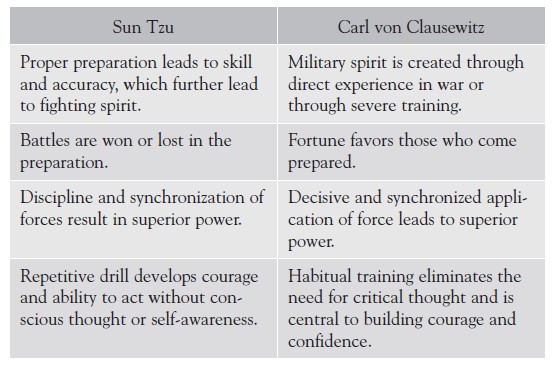

In Europe, drill likewise built courage and confidence and helped soldiers come to terms with the uncertainties of war. Carl von Clausewitz acknowledged that combat plans tend to fall apart once the first blows are exchanged, yet fortune favors those who come prepared. The various frictions he described can be overcome at least partially through routine work and genuinely tough training. Although he emphasized physical strength directed at the opponent’s center of gravity, or the balance point against which an attack will cause the enemy to collapse, moral strength, or the ability to operate efficiently in the face of adversity, is gained through habitual training. Habits are built through drill. Drill is built on prescribed patterns of training that bring the martial artist to a position of familiarity under stress. Recognition and knowledge of these patterns lead to mental strength and fortitude. We have thus come full circle, or back to what Sun Tzu identified as ch’i.

In ancient and modern times, specific exercises have been used to prepare soldiers for the demands of the battlefield. It was well understood that he who had superior physical strength and endurance had a better chance of surviving the rigors of war than he who did not. In personal combat, a muscular and supple body that communicates strength and readiness to fight can also give one psychological control over the enemy. The exercises used in ancient times to build a fighter who was strong in body and spirit differed not too much from those relied upon today. Training and drill are keys to combat efficiency; their purpose is to develop a fighter who can endure and win. This chapter demonstrates why habitual exercises increase physical skill, mental discipline, and courage, and help the martial artist perform with precision in the training hall and in encounters of life and death.

Key Points: Preparing for Battle

Intense training prepares the martial artist to endure physical and mental hardship. Endurance, in turn, leads to combat efficiency. Although also serving a ceremonial function, the purpose of drill has historically been to prepare troops for battle and familiarize them with the conditions under which they must fight. General Wu Ch’i of Wei of the Warring States period said, “Now men constantly perish from their inabilities and are defeated by the unfamiliar.”4 In addition to giving armies the capacity to maneuver large forces efficiently into positions that maximize power, drill is meant to closely mimic the tactical moves individual soldiers are expected to use on the battlefield and allow them to respond to commands without hesitation. As movements are perfected and mistakes minimized, drill instills confidence. As confidence grows, pride, poise, and a sense of team spirit follow. Some historians consider near modern China’s contempt for drill for fighting purposes central to China’s loss to Japan in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-1895 CE :

[T]he lack of drilling not only undermined the effectiveness [of] the firepower of the Chinese troops despite very good weapons, but it also undermined the discipline of the army and its commitment to fight. In this respect, the Chinese army stood in stark contrast to the Japanese army. [T]he importance of drill lies not only in enhancing the effectiveness of firepower and the efficiency of the army, but also in improving the discipline and morale of the army.5

In contrast to the above statement, discipline in ancient China was valued to the point that capital punishment was inflicted on those who refused to act as prescribed. As recorded in the Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yüeh, Sun Tzu was brought before the King of Wu to demonstrate how to form untrained troops into attentive and cohesive combat units. He first ordered the king’s three hundred concubines to form into an army, with two of them acting as company commanders. After ensuring that they had received instruction in military methods, he had the company commanders order the rest to assemble, advance with their weapons, and deploy into military formation. When the women covered their mouths and laughed, Sun Tzu informed the king that if the instructions were not clear and the soldiers did not act as directed it was the fault of the commanding officers. Failing to lead and instill discipline in the troops was punished by decapitation. He then had the two concubines acting as company commanders decapitated. The next time Sun Tzu beat the drums and ordered the women into military formation, they advanced and withdrew “in accord with the prescribed standards without daring to blink an eye.”6

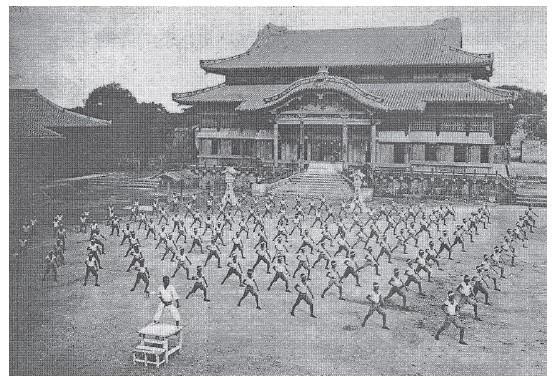

Sun Tzu further related in the Art of War that the reason why soldiers were taught to perform in unison and remain focused on the task at hand was to prevent fear and desertion caused by excessive thought: “Now, gongs and drums, banners and flags are used to unify the action of the troops. When the troops can be thus united, the brave cannot advance alone, nor can the cowardly withdraw.”7 Consider your dojo or training hall. When drilling the basics and shouting loud kiais (or kihaps) in unison with your peers, the group absorbs your identity and contributes to each person’s individual power. Historically, the kiai might have stemmed from a reaction to danger and an effort to summon assistance from friends. In a similar manner, when gongs or drums are sounded before a kungfu competition, it gathers the audience’s attention and unifies the people, raising the spirit of the fighters. It may also place fear in the opponent. Most people will agree that the sound of gongs or drums has a psychological effect on fighters and audience alike by bringing purpose to action. Music or drums have served important functions in all military cultures by instilling discipline and fighting spirit in the warriors. The ancient Chinese classic, The Methods of the Ssu-Ma, explains how a soldier, “when he enters the army and takes control of the drumsticks and urgently beats the drum he forgets himself.”8

While the victory is prepared in the planning by studying the political situation, the terrain, and the fighting habits of the respective armies, drill and constant repetition of techniques give the soldiers the skill to make quick and resolute decisions when crisis strikes. In accord with knowing yourself and your enemy, Sun Tzu asked us to think about in which army, yours or the enemy’s, regulations and instructions are better carried out, and “[w]hich army has the better trained officers and men.”9 Forces must be synchronized to defeat the enemy quickly and with minimum wasted motion. Consider how a perfectly timed strike in the martial arts with all your body’s mass behind it may seem almost effortless, yet has the power to knock out your opponent. “[T]he energy of troops skillfully commanded in battle,” Sun Tzu observed, “may be compared to the momentum of round boulders which roll down from a mountain thousands of feet in height.”10 As reinforced by Chinese military strategist and statesman Zhuge Liang (181-234 CE) in his classic text, The Way of the General :

In military operations, order leads to victory. If rewards and penalties are unclear, if rules and regulations are unreliable, and if signals are not followed, even if you have an army of a million strong it is of no practical benefit. An orderly army is one that is mannerly and dignified, one that cannot be withstood when it advances and cannot be pursued when it withdraws. Its movements are regulated and directed; this gives it security and presents no danger. The troops can be massed but not scattered, can be deployed but not worn out.11

Drill and ritualized training, such as striking or kicking the air, mitts, or bags repeatedly also benefits the martial artist because it accustoms him to the rigors of combat, trains his body and mind to endure hardship, and teaches men and women of different backgrounds and temperaments to use their martial art judiciously. The common rules of dojo etiquette in the traditional martial arts include displays of courtesy such as bowing when entering or leaving the training hall and prior to and following technique practice and free sparring; wearing a traditional uniform or gi to impart integrity and reverence for the art; and lining up according to rank. Many martial arts schools also employ some kind of oath or creed intended to promote reflection on the art, such as an affirmation of one’s intention to develop discipline and only use the art for the defense of self and others.

Karate training at Shuri Castle, Okinawa, 1938. Synchronization of movement, which is achieved through drill, is valuable to the individual martial artist because of the power it provides. The perfect stance, for example, gives you balance, enabling you to transfer force from your foundation to the strike or kick through hip rotation. (Image source: Nakasone Genwa, Wikimedia Commons)

When speaking of drill, we do not only mean punching, kicking, and blocking, but also static exercises such as stance practice and meditation. A military recruit or sentry who has to stand at attention for long periods of time, in heat and cold, in rain and snow will at first find the exercises unbearable. But each session brings him more confidence and the belief that he can endure until the end, as his body is strengthened and his mind learns to control his emotions. The martial arts student who is made to stand in a continuous horse stance will likewise steel his body against pain and discomfort, and his heart against distractions and boredom. Such motionless practice instills perseverance and heightens one’s senses to the surroundings. For example, in feudal Japan, the ninjutsu fighter, known for espionage and clandestine practices, needed patience and ability to move about in the environment without risking detection. Walking noiselessly through grass or vegetation required superb balance and total control of muscle movements as he carefully shifted the weight from one foot to the other. Once you get used to drill, whether stance practice or technique training, you may even begin to find it relaxing, because it teaches you to respond to commands without hesitation, effortlessly and without excessive thought, and enables you to do the techniques required of your art in the most efficient way possible.

Drill further helps prevent injury and instill confidence by minimizing fear. Ch’i, a fundamental concept of the Asian fighting arts, relates to the physical and metaphysical realms. “The ancient Chinese created the character for ki [ch’i] using the radical for ‘gas’ or ‘steam’ and the radical for ‘rice.’ Noticing the steam rising up from the boiling rice inspired the notion of something material out of this world and something really not there.”12 Passages in Chinese writings further describe ch’i as vitality, the breath of life; and also the mist, smoke, or cloud formations rising from the enemy’s positions, which shape and direction of flow will predict the outcome of battle. However, ch’i can best be understood, perhaps, if thought of as fighting spirit. Your goal is to use your high spirit to destroy your opponent’s morale. As explained by Hirokazu Kanazawa, a renowned karate teacher, there is a strong connection between breath and fighting spirit. For example, most of us are familiar with the idea of exhaling at the exertion of a move. If you participate in contact sparring, you also know that taking a strike to the abdomen or solar plexus while inhaling may drop you to the ground. The kiai yell teaches you to tighten your abdomen at the exertion of a technique or at the reception of a blow, and decreases the risk of injury. Thus, “[i]f your breathing is wrong, your body will be wrong and your mind will be wrong.”13

Furthermore, a clear understanding that you can lose your life in a physical confrontation should prompt you to take your training seriously and eliminate wasteful practices. Shouting and tensing at the moment of impact even when striking the air, communicates to a potential opponent that your techniques are powerful enough to kill, or at least end the fight. One Hapkido master suggests training as if your life depended on it. For example, if your opponent chokes you, be determined in your escape, because you only have seconds to execute it and walk away with your life intact.14

Although some say that ch’i fails to mesh with reality and “won’t save you from a beating,”15 the ancient text of the Chinese military classic, Wei Liao-Tzu, notes that victories were not divinely inspired, but “were a matter of human effort.” If you fail, there are practical reasons, for example, because you are undertrained or “the walls are high, the moats deep.” Ch’i is not something mysterious, and “[p]utting spirits and ghosts first is not as good as first investigating [your] own knowledge.”16 Sun Tzu reinforced this statement when he noted that “fore-knowledge cannot be elicited from spirits, nor from gods, nor by analogy with past events, nor by astrologic calculations. It must be obtained from men who know the enemy situation.”17

The martial artist attains ch’i by conducting an honest assessment of his strengths and weaknesses, and through regular training that accustoms the body and mind to the strains of combat. Kata (forms practice) in the traditional Asian martial arts is a valuable training device that spurs the development of fighting spirit. Since people were largely illiterate, kata were essentially “books” that enabled techniques to be passed down to future generations. Furthermore, many techniques in ancient times were meant to work against an opponent wearing armor and had to be modified when practiced against unarmed training partners. Kata allowed a student to practice techniques that could kill without harming his partner.18

In addition to conditioning the body for the moves required of the martial art and giving the fighter endurance through extended practice, kata developed mental discipline by teaching precision in technique and instilling muscle memory and ability to act under stress. Perhaps most importantly, kata helped the martial arts practitioner form habits which allowed him to take a definite stand in battle and avoid confusion and uncertainty. He could now act without conscious thought or self-awareness, confronting his fear of death and drawing strength from the Buddhist concept of nonattachment. In China, emptiness, as when the mind is not obscured or confused, as explained in T’ai Kung’s Six Secret Teachings, allowed one to discern things that were not manifest,19 and proved effective, for example, in deceptive practices requiring the anticipation of battle. The moment the soldier established individual identity, the principle of nonattachment would fall by the wayside. In Japan, as taught by samurai retainer Yamamoto Tsunetomo in the “lesson of a downpour,” when accepting one’s fate, one can remain tranquil even in death: “A man, caught in a sudden rain en route, dashes along the road not to get wet or drenched. Once one takes it for granted that in rain he naturally gets wet, he can be in a tranquil frame of mind even when soaked to the skin.”20

Technique practice according to prescribed patterns and prearranged sparring complement kata by familiarizing the martial artist with combat, making fighting instinctive, and eliminating excessive thought. At the lower levels, techniques are done in unison according to a standardized pattern to train certain body mechanics in the beginner martial artist, allowing him to draw strength from his peers. As we advance, techniques can be changed to suit our individual talents and inclinations. “For an art to be alive,” as explained by martial artist and traditional Chinese medicine physician Mark Cheng, “it must be functional for a variety of people, each with his own attributes and weaknesses.”21

Since ancient martial arts practiced today are still evolving, we naturally see a wide range of variations within an art. However, the basic principles and combat applications are retained. For example, China, the birthplace of kung-fu, has seen this ancient art develop and branch into several hundred distinct styles; although, not all emphasize combat. Originally referring to any great skill (if a person were skilled at calligraphy or cooking, for example, one would say that his kung-fu was good), kung-fu and its many internal and external variations was designed to develop mental strength and physical fighting prowess, reflecting the culture of the particular region in which it was practiced. People from the arid steppes of northern China naturally practiced a different variation of the art than people from the more forested southern regions; thus, the distinction between northern style kung-fu (linear attacks based on strength and speed) and southern style kung-fu (circular attacks based on intricate footwork and timing).22

Kung-fu practitioners may train in tactics as varied as long range strikes and kicks with a swift closure of distance and power derived from the waist and shoulders, to acrobatic styles employing mainly high kicks, or close range fighting involving relentless attacks to the legs. The Shaolin method of Chinese boxing, which emerged from the Shaolin Temple near Zhengzhou City Henan Province, was particularly known for its rigorous training practices which focused on strength, speed, and flexibility. The word kung-fu, which refers to an unerring devotion, fostered the idea that in order to be in control of a combat art, one must dedicate oneself fully to its purpose and train with intent. First then can it be said that one’s kung-fu is good. Although a skilled kung-fu practitioner would travel to different regions and learn from a variety of teachers, he would naturally favor a few specific hand, foot, or weapon techniques, which he would master to perfection.23

Because of its remote location, the Shaolin Temple was prone to attack by bandits, and its inhabitants felt prompted to learn kungfu for self-defense. Using everyday tools and farming implements as weapons, the monks established a long and rigorous training regimen in self-defense tactics. Learning a strong stance gave them the power to withstand an opponent’s attack. To maintain strength, it was argued, stance, although basic, must be practiced for an hour or two everyday throughout the martial artist’s life. There are no shortcuts in kung-fu. Only total devotion and endless practice lead to powerful techniques. Other exercises, such as slapping water in a barrel hundreds of times on a freezing cold day, were developed for increasing mental toughness, which was often considered more important than physical toughness. Kung-fu is based on a methodology of constant repetition to instill muscle memory and make each action second nature, giving the martial artist the power to act and respond automatically and in the most efficient way possible when under threat.24

Gate of the Shaolin Temple, known for its disciplined and rigorous martial arts training and drills. (Image source: Cory M. Grenier, Wikimedia Commons)

In modern China, sanda, a form of freestyle boxing based on traditional kung-fu, is taught to the roughly two million soldiers of the Chinese military, the largest standing army in the world. Relying on the four tactical elements of punching, kicking, grabbing, and taking the adversary to the ground, for example, by catching his kicking leg and sweeping his supporting foot, sanda is a modern incarnation of ancient mixed-style kung-fu and wrestling and displays many similarities to Western kickboxing and Muay Thai. Although the traditional Asian martial arts are often portrayed as gentler and more compassionate than their Western counterparts, Asian records talk about approaching any combat situation with a readiness to kill. The sanda training regimen, focusing on stamina, physical strength, proficiency in technique, and the acquisition of a mental edge over the adversary is grueling and undertaken in accord with the Chinese saying, “train either in the hottest days in summer or the coldest days in winter.”25

The West has historically employed many concepts nearly identical to the Asian practices. Military spirit acted as a guide to the individual soldiers when clear directions were missing. According to Clausewitz, there were two ways in which to create spirit for this purpose: frequent wars or severe training.26 Conceptually, repetitive drills performed in the Western armies, including today’s armed forces, differ little from kata and the prearranged training patterns of the traditional Asian martial arts. Military drill, like kata, teaches attention to detail while making movements responsive to outside stimuli. As Clausewitz pointed out, “War is the realm of physical exertion and suffering. These will destroy us unless we can make ourselves indifferent to them, and for this birth or training must provide us with a certain strength of body and soul.”27 When thoughts of death crept into the soldier’s mind, he was no longer an effective fighter. Repetitious training according to prescribed patterns has historically allowed soldiers to fight in large formations, by coordinating movement and eliminating cowardice and desertion.

It was also reasoned that men who were too independent generally did not have the caliber to be good soldiers in mass armies; they could not fight well as a team and were unwilling to take orders or endure the punishment that came with disobedience. When men in formation came to realize that they were not a unit but individuals with hopes, dreams, fears, and desires, thoughts of desertion would manifest. The armies of Classical Rome were particularly known for valuing and standardizing drill through disciplined ritual and training, which would hold the phalanx together, allowing it to amass maximum power at the critical point.

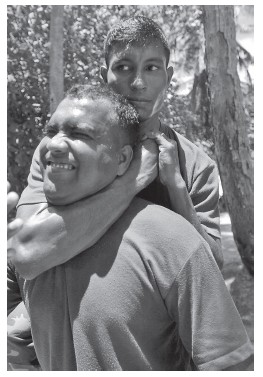

Stranglehold. Practicing your martial arts techniques with intent will give you a near realistic experience and spur proper reactions. (Image source: Cpl. Benjamin M. George, Wikimedia Commons)

As explored in chapter 2, Clausewitz further noted that knowledge of combat is easy to articulate but difficult to apply, and that which is unfamiliar can easily lead to perplexity and inability to act with determination. A fighter who has practiced a particular technique only once has a clear advantage over he who has no familiarity with the technique at all. But repetitive drill that largely eliminates the need for critical thought is ideal over piecemeal practice, and is instrumental in building confidence and freeing the martial artist from doubt. As stated by the Greek general and historian Xenophon in the fourth century BCE, “[W]hichever army goes into battle stronger in soul, their enemies generally cannot withstand them.”28 As reinforced two and a half millennia later by former West Point psychology professor Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, “The student’s experience in training helps to take some of the surprise out of it when the real situation arises. Effective training also elevates the student’s sense of confidence.”29 Martial art training done with intent using at least some physical contact will spur familiarization with potential combat situations. For example, if an adversary grabs you in a rear choke, you will know not to panic and hopefully react with the defensive technique you have learned without further thought.

The need to respond to uncertainty and changing conditions requires talent, or innate ability, which the martial artist can nurture by engaging in relevant training maneuvers prior to battle. Physical preparation may even be more important for preparing the mind than preparing the body for combat, teaching one to act rationally and with determination when under attack. As stated by military historian John Keegan, “That aim, which Western armies have achieved with remarkably consistent success... is to reduce the conduct of war to a set of rules and a system of procedures— and thereby make orderly and rational what is essentially chaotic and instinctive.”30 Uncertainty will rob a fighter of his spirit, as will fatigue. You may be an exceptionally talented martial artist with twenty years experience under your belt, but when fatigue overcomes you, all of the techniques you have learned and practiced to perfection will instantly become useless. The risk of premature fatigue decreases with intense physical training, thus giving you the mental edge you need to defeat the adversary.

Practice must also be extensive enough to make the moves habit when performed under stress where fine motor skills tend to deteriorate. Instructors of the Israeli hand-to-hand integrated combat system haganah (defense) take advantage of habitual training patterns by limiting practice to a few techniques, bringing the fighter to a point of familiarity under stress no matter what type of attack he is defending against. The art’s effectiveness is derived from the fact that each technique focuses on achieving a common objective, such as taking an empty-handed opponent to the ground without going down with him or unarming a weapon-wielding opponent with the intent of restraining, incapacitating, or killing him.

For example, if you are engaged in a knife-on-knife altercation and the opponent attacks with a slash toward the left side of your neck, you might block his knife hand, slash his wrist, slash his abdomen, stab to his kidney, and slash his leg to take him down and prevent him from continuing the fight. Now, let’s say that his initial attack misses because you anticipate it and moved your upper body to the rear. The opponent may now try to counter with a backhand slash to the right side of your neck. But since you have learned to create a point of reference, you know that you are in position to use the same defensive sequence as you would have used had you not moved away from the initial attack: Block his knife hand, slash his wrist, slash his abdomen, stab to his kidney, and slash his leg to take him down and prevent him from continuing the fight. The only difference is that the first defensive sequence is done from an angle along the opponent’s centerline (inside technique), while the second defensive sequence is done from an angle away from his centerline (outside technique).

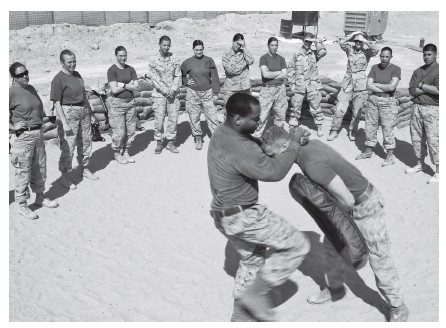

U.S. Marines practicing the knee strike. If you learn the martial arts by creating a point of reference, as done in the Israeli haganah combat system, your muscle memory will tell you after sufficient practice that a simple technique such as the knee strike can be used any time you are in position to grab the opponent’s neck. (Image source: Sgt. James R. Richardson, Wikimedia Commons)

The same principles can be applied to an empty hand technique. If the opponent attacks with a right punch, you might block the strike to the inside of his arm and then grab his neck and knee him in the groin. If he throws a left punch, you might block the strike to the outside of his arm and then grab his neck and knee him in the groin. You know that your defense will work because you have created a point of reference (a familiar situation) that tells you that every time you are close enough to block the opponent’s strike, you are also in position to grab his neck and throw a knee to his groin or abdomen, no matter what his original intent.

The drills you practice in the training hall are thus designed to improve fighting skill, reflexes, aggression, purpose, and conditioning (physical and mental). However, they are not meant to prepare you exactly for how the battle will go down. Clausewitz stressed that there is no single standard that guarantees success in warfare, and even “mercenaries and forcibly controlled peasants” can prove just as effective, for example, as the citizen-soldiers of Revolutionary France.31 You can test this principle by rhetorically asking who will win a street confrontation: a black belt martial artist or a street thug who has never set foot in a dojo. Ultimately, how successful you are depends on a variety of factors, such as the intensity and intent of your training, your physical size and health, and various frictions, such as fatigue and surprise.

Furthermore, a prearranged defense to a particular offense; for example, a block followed by a front kick as defense against the opponent’s punch, should be done with the understanding that the drill is merely one of many possibilities. Free-play exercises that approximate the conditions of combat and promote independent thinking are also necessary to reach success in the art of war. Repetitive drill and training along with critical analysis prior to battle decrease the risk of making irrational decisions that lead to dangerous losses. To increase analytical skill and learn to adapt to changing circumstances, set aside time in the training hall for asking, “What if?” and analyze the possible motivations behind an attack prior to the engagement. Does the adversary want to rob you? Rape you? Humiliate you? Kill you? Does he act out of self-preservation? Does he merely respond to a threat or a perceived threat? If you remove the threat, might there be no fight and you can both walk home safely?

The lesson one should learn is that, although it is not possible to ensure victory through training alone, proper preparation familiarizes the martial artist with events that will likely occur on the field of battle or in the sports arena and decreases the risk of going forward blindly. As Clausewitz stressed, one should start from the reference point of the ideal, yet acknowledge that the battle plan will need to be modified. The more familiar one is with the situation, the greater the chance of reaching success. French emperor and military leader Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821 CE) may have had a valid point when he said that “the moral [courage and fighting spirit] is to the physical as three to one.” A clear definition of the goal along with good preparation will bring you closer to the ideal form of war by giving you confidence and ability to get back on track when things go awry. Additionally, a person who is rightly prepared has truly considered the complexity of the situation at hand and understands the challenges. You will have a better experience in the dojo if you succumb to the ritualized training practices, than if you question the validity of every move the instructor asks of you. According to Clausewitz, the trick when the losses one suffers on the battlefield undermine courage and fighting spirit is “to make the experience of battle work to the benefit of morale.”32

As demonstrated in this chapter, both Asian forms practice and Western drill are important for preparing the martial artist for the disorder of the battlefield and the sports arena. Habitual training gives you the power to act instantaneously without thought in the midst of chaos. Whether we call it kata, poomse, shadow boxing, or bag work is less important than is its purpose to instill discipline, determination, and courageous performance without thoughts of injury or death. Although actual trials in combat will increase your confidence and enable you to come to terms with uncertainty, British military historian Basil H. Liddell Hart (1895-1970 CE) reminds us that there are “two forms of practical experience, direct and indirect—and that, of the two, indirect practical experience may be the more valuable because it is infinitely wider.”33 Since a soldier or martial artist has few opportunities to gain direct experience in combat, disciplined and semi-realistic training exercises with one’s peers are “infinitely wider” and, therefore, the best alternative.