CHAPTER 4

ELEMENTS OF TACTICS

AND STRATEGY

“All warfare is based on deception.”

—Sun Tzu

“Surprise is the most powerful medium in the art of war.”

— Carl von Clausewitz

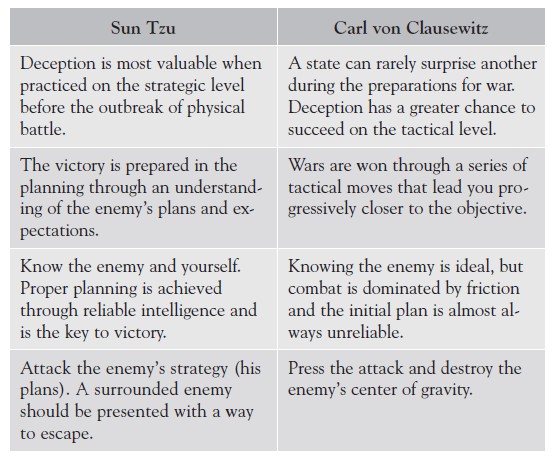

As demonstrated in the previous chapters, the martial arts can be divided into preparations for combat and acts of combat. A fight is seldom concluded through one decisive move, however, and both fighters will consider the other’s actions and adapt accordingly. Strategy is the master plan that creates the conditions for battle, but the fight is ultimately won through a set of tactical moves that progressively lead the martial artist closer to the goal. Tactics are used to advance the political objective and must be employed with purpose. Since the risk of injury or death in war has historically been great, one must avoid wasteful practices and know the enemy well enough to understand whether or not victory can be achieved. Or as Sun Tzu reminded us, “Act when it is beneficial, desist if it is not.”1 Carl von Clausewitz likewise stressed that the probability of victory must be on your side before you decide to engage in battle. This is true whether or not you are holding an advantage in physical strength.

Before taking action, one must further determine the opponent’s objectives, study his strategy, and decide what motives are worth fighting for. A martial artist engaged in competition, might discover that the opponent, a taekwondo practitioner, prefers kicks to hand techniques and generally throws his kicks high. If taekwondo is the primary art of both fighters, the best high kicker may win. But if one fighter favors kickboxing, he might decide to undermine the opponent’s foundation by kicking his supporting leg the moment he raises his foot off the ground. If the taekwondo practitioner is carrying his hands low, it might invite the kickboxer to exploit this weakness by positioning away from the attack line and striking the head. Although the kickboxer’s strategy involves negating the opponent’s strengths and taking advantage of his weaknesses through superior positioning, the particular body part (hand or foot) used to target the head and the particular way by which it is done relate to tactics.

If engaged in a more serious life or death drama where a weapon is involved, your strategy might be to neutralize the threat (the opponent’s weapon hand) before attacking a vital target (his eyes, throat, or groin), and then ensure that he cannot continue fighting by taking his foundation. Your strategy is your grand plan. Note that nothing has been specified with respect to how you neutralize the threat, attack a vital target, or take the foundation. These are elements of tactics and refer to the particular moves you use within the fight, such as strikes, kicks, and sweeps. Thus, your strategy (neutralize the treat, attack a vital target, take the foundation) leaves a number of options to choose from. For example, you might trap the opponent’s weapon hand, strike his eyes with your fingers, and dislocate his knee with a kick in that order. But you would not attack his forearm after you have disarmed him, because his forearm is not a vital target and would not advance you closer to the objective of rendering the opponent harmless. Knowledge of the enemy is crucial in order to determine what kinds of tactics to use and whether or not the battle is worth fighting. Different tactics will be employed depending on the enemy’s political objective. Does he want to rape or kill you? Does he want your wallet?

A fighter who develops good strategy but cannot execute it tactically is not likely to succeed in single man combat. If the tactics are poor, you cannot hope that the strategy will save you. And if the tactics are poor, you are unlikely to be successful in the art of war. You will not always know what types of tactics to use prior to engaging an opponent in battle, however. But he who is well-trained in the use of different tactics and understands the strategy can adapt during the fight and still reach the objective. This chapter demonstrates that when the strategy has been determined, tactical planning must be adapted to fit the changing circumstances of battle. Or as Sun Tzu said, one should “take the field situation into consideration and act in accordance with what is advantageous.”2 Clausewitz agreed. Due to the uncertain nature of war, one cannot predict the enemy’s actions from one moment to another but must remain flexible enough to adapt.

Key Points: Elements of Tactics and Strategy

Those who excel in warfare rely on a strategic configuration of power. According to Sun Tzu, skilled strategists are “like a fully drawn crossbow; their constraints like the release of the trigger.”3 Strategy is about determining when, where, and how the tactics will be delivered. The reason why strategy (or advance planning) is important, perhaps particularly in a martial art that relies overwhelmingly on the physical engagement, is because good strategy allows the martial artist to break the opponent’s resistance physically and mentally before deploying the specific techniques that end the fight. The victory is thus prepared in the planning.

A good strategist can engage a numerically superior enemy with inferior strength and still be successful. As noted in chapter 1, Sun Tzu emphasized diplomacy over physical battle and regarded the ability to break the enemy’s resistance without fighting the apex of excellence. But diplomacy, the art of playing to the opponent’s interests, works only if one first acquires a thorough understanding of his needs and desires. Even then, there are times when diplomacy will fall by the wayside because the price is greater than the value. This might be the case, for example, when your life is directly threatened. Sun Tzu advised us to fight courageously when on “desperate ground.”4 Moreover, the person who attacks you has likely determined beforehand that he has the capacity to beat you. When he brandishes a knife, it is in the belief that you will succumb to his will.

What should you do? You may start by attempting to calm the situation through diplomatic means, by assuming a non-threatening stance, keeping your distance, asking that he puts the knife away, offering him your wallet, or apologizing for whatever offense he is accusing you of. But if none of this works and he advances toward you nevertheless, decisive physical action is necessary. If you too have a knife or weapon that you can show the opponent, you may be able to shift the leverage in your favor. The opponent, knowing that he will not walk away unscathed, may now find the time ripe for diplomacy and take you up on your attempt to resolve the conflict without bloodshed.

Although Clausewitz was not against diplomacy per se, he considered combat the only effective means by which to win a war. One of his key recommendations involved attacking the adversary’s center of gravity, the balance point of his collective strength. For example, a taekwondo practitioner who is exceptionally well-versed in high and powerful kicks will be at a physical loss the moment you take him down through a brutal attack to his supporting leg. When you destroy his physical capability to kick, you will simultaneously sabotage his courage and fighting spirit and thus break his resistance mentally. In fact, a martial artist’s center of gravity may well be his mental strength. Clausewitz stressed that the moral elements of battle (courage and fighting spirit) are “completely fused” to the physical forces: “... we might say the physical are almost no more than the wooden handle, whilst the moral are the noble metal, the real bright-polished weapon.”5 Victory requires more than good technique. Humiliating the adversary or breaking his confidence may be the strategy you choose for subduing an aggressive opponent.

The purpose of strategy is to break the opponent’s resistance. Attacking his center of gravity; in this case his ability to kick high, by timing a front kick to his midsection each time he raises his leg to kick will rob him of his fighting spirit. (Image source: Alain Delmas, Wikimedia Commons)

Whether or not you achieve the objective is the ultimate judge of whether your strategy is sound or flawed. When the objective is clear, the strategy can be executed through the use of proper tactics. However, the possibility exists that the tactics, the tools you use to reach the objective, prove unsuitable for the particular opponent you are facing. Using a hook punch to neutralize the hook punch of a good boxer, for example, will merely pit strength against strength. Using upper body movement, a bob and weave, to neutralize his hook punch and establish a superior position away from his attack line followed by a strike to his jaw to knock him out, demonstrates a sounder use of tactics. It may also be that the taekwondo practitioner you were fighting earlier, whose trademark is the high and powerful kick, has superior speed, coordination, and timing due to extensive practice and knocks you out before you get within range to take him down through an attack to his supporting leg. Although the victory is prepared in the planning, the various frictions of which Clausewitz spoke tend to interfere with the best-laid plans.

Proper tactics begin with stance. The fighting stance, a fundamental concept of the martial arts, was directly influenced by the local terrain in which battle was fought and the type of enemy one expected to face. A proper stance could mean the difference between life and death and was designed to give the fighter stability, power, and strength in defense. A wide horse stance allowed him to maintain balance on uneven ground and avoid an attack by shifting his weight sideways. Consider the defensive posture of a judo practitioner, feet apart and body lowered by bending the knees, which prevents him from being unbalanced or thrown. Stances were further developed for fighting in enclosed areas which restricted the use of footwork and movement. If an attack could not be avoided through movement, the fighter could absorb the blow by bending his knees and sinking into a lower stance.6

Additionally, stance served a mental function by allowing the fighter to establish command presence. Displaying confidence through stance indicates physical and mental readiness and might give the martial artist the power to win by intimidation alone; thus, winning without fighting, which Sun Tzu prescribed as the best way to victory. If this is not possible, the Chinese classics advocate thwarting the attack rather than facing the adversary head-on.7 Since successful warfare requires adaptation, however, a warrior must modify his stance to suit the circumstances of combat and his personal physical build. This is why some of the traditional stances seem less relevant to the modern martial artist participating, for example, in no-holds-barred combat relying on quick footwork and a mix of stand-up and ground fighting techniques.

Generally, the stances used in the Western martial arts vary less than those typically seen in the traditional Asian arts. A boxing stance places the fighter sideways, knees slightly bent, and with the dominant foot to the rear. Swordsmanship in the medieval era in Europe did not advocate any particular stance, but propagated the idea that the knight should use whatever footwork he found to be the most beneficial. Although a number of postures or guard positions were taught, rather than keeping one side of his body facing the opponent, the knight could strike with the sword equally well from a left or right stance, and would advance in an alternating stride to speed up movement and increase the reach and power of the attack. Balance and agility were still central to stance and, most importantly, a stance was not static.8

Ground, or the environment, is yet a crucial factor of war which guides the martial artist in his choice of strategy and stance. When Sun Tzu spoke about posture, his reasoning did not stop at the particular stance of the individual soldier, but extended to the strategic positioning of the army. The goal was to gain as much mobility and flexibility as possible. He listed six types of ground and how to fight on each. Some comprised long distances, others short; some were treacherous, others more secure. He called ground easy to reach but difficult to get out of entangling ground; its nature being such that one can easily defeat an enemy who is unprepared. Terrain equally disadvantageous to both belligerents he called temporizing. Such ground would prompt one to use deception by drawing the enemy forward and striking from a position of strength.9 When studying stance, one might keep in mind that China has historically fought lengthy battles against nomadic warriors of considerable equestrian skill, who, because of their ability to live off the land, could mount swift attacks and disperse just as quickly.

Martial artists exploring the practicality of their techniques in difficult terrain. The Chinese martial arts use many stances that prove particularly suitable for wielding weapons. (Image source: Aldhous, Wikimedia Commons)

The terrain in which one fights can thus be a hindrance, but it can also be utilized to the martial artist’s advantage if he has studied it in advance and is well schooled in its use. Clausewitz noted how the terrain offers several advantages, such as obstacles to the opponent’s advance or the ability to check attacks to one’s flanks. For example, if you find yourself in a multiple opponent scenario, a doorway may be used to check the enemy’s advance or guard against attacks to your flanks or rear, because a large group of fighters cannot pass through a narrow opening at one time. In China, there is a saying: “With only one guarding the mountain pass, ten thousand men are not able to pass.”10 Thus, a single man does not need overwhelming physical strength to fight multiple opponents as long as he occupies advantageous terrain. In Western military history, the battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE offers a revealing example of how a much stronger enemy can be stalled by a few men through the skillful use of terrain. A force of merely three hundred elite Spartan warriors fighting under King Leonidas I of Sparta, in addition to a few thousand Thespian, Theban, and other assistants were able to stall the Persian army fighting under the Persian Empire of Xerxes I, allegedly numbering in the millions (per Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus). Only after the Spartans had suffered betrayal did the Persian army manage a breakthrough and ultimately surround and kill the Spartans to the last man.

Using the environment to your advantage, for example, placing your back against the ropes can protect your rear and flanks, but it can also limit your mobility and cut off your escape routes. (Image source: U.S. Military, Wikimedia Commons)

Although many Asian martial arts seem shrouded in mysticism to the Western practitioner, Sun Tzu was a practical person who stressed the importance of seizing the initiative and shifting the balance of power in one’s favor through the use of cunning and surprise. The deceptive army takes advantage of opportunities through swiftness and flexibility in movement and amasses full force against the critical point, ending the fight in minimum time and with as few losses as possible. Deception on the strategic level is based on good intelligence. How does the enemy think? What are his plans? What does he fear most? If you know his fears, you can capitalize on them and make him stage troops, for example, at an area he does not need to defend and that you do not intend to attack.

An enemy who believes that you will meet him in frontal assault will fail to guard his rear or flanks. Consider the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca, who became famous for the deceptive pincer movement he used to defeat the numerically superior Roman army in the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE. The maneuver relied on drawing the enemy into a trap and cutting off the escape routes. The reason why Hannibal Barca succeeded was because he created the illusion that his own forces were retreating by drawing back the center of the line, tempting the enemy to move forward. This maneuver allowed his relatively sparse forces to envelop the enemy and attack the flanks and rear where they were unprepared. But success depended on an opponent who was willing to engage in direct battle. Sun Tzu warned against trying this maneuver against an adversary who was prone to running. He even encouraged leaving the enemy an escape path because an army that is left with no way out, he argued, would fight to the death and cause great devastation in both armies: “For it is the nature of soldiers to resist when surrounded, to fight to the death when there is no alternative.”11

Deceptive moves must be convincing in order to have value. In the martial arts, a broad shift in weight, for example, can create the illusion of forward or reverse movement and cause the opponent to move into the power of a strike. The drunken style kung-fu practitioner hides his intents by relying extensively on deceptive body movements, launching his strikes from unexpected angles and disrupting the opponent’s concentration. (As Sun Tzu said, “A confused army leads to another’s victory.”12) Yet he stays in full control of his body by using the strength of his core (abdomen) to maintain balance. Drunken style kung-fu, which was popularized by actor Jackie Chan, has roots in many styles of traditional Chinese martial arts. It may have been created at the Shaolin Temple, “or by warriors posing as Shaolin monks who, no doubt, would often drink alcohol, and who later developed a system based on the emboldening qualities of alcohol.”13

Capoeira, a Brazilian martial art founded several hundred years ago by African slaves, likewise relies extensively on deceptive and evasive body movements, with attacks focusing on leg sweeps and kicks from unusual positions. The practitioner of this art might appear to attempt a spinning leg sweep by dropping his bodyweight, but throws instead an unexpected spinning heel kick to his adversary’s head. The art naturally requires great athletic ability. A skilled capoeira practitioner can reach tremendous speed in a spin kick and can easily knock his opponent unconscious. Small body size might actually benefit him because of the lower energy requirement of moving a small body and the greater ease with which he can gain speed in a spin kick. A fighter relying on a more direct approach to combat may beat a capoeira stylist by launching a strike when the opponent is in the middle of a complex maneuver such as a cartwheel. But such an act requires good timing. Timing is not about speed, strength, or superior physical build, but about the ability to strike a precise target when the opponent least expects it and preferably when he is moving into the strike’s path of power. The consequence of taking a strike from a big fighter in possession of superb timing will be particularly devastating to the capoeira stylist because of the tremendous speed with which he moves his body. He might, in effect, knock himself out against the opponent’s fist.

Good timing can also create sensory overload, a state of confusion and chaos often experienced by a fighter who is attacked repeatedly with explosive combinations. The concept of flow, as noted in chapter 1, is about avoiding a strike while remaining in position to strike the adversary. Thus, Sun Tzu’s saying that “the momentum of one skilled in war is overwhelming, and his attack precisely timed.”14 Flow, a concept of deep importance in the Asian martial arts, further relates to rhythmic movement, the maintenance of proper distance in an engagement, and mental stability. “According to Far Eastern thinking, all of life is flow. You must learn to move and conduct your affairs in harmony with the universal scheme of things so you may master the art of living.”15 The Western world has adopted elements of flow along with the complementary opposites of yin and yang in modern warfare. A 1989 U.S. Marine Corps manual based on Clausewitz’s teachings notes that combat is comprised of two essential components: fire and movement. These appear to represent opposite ends of the spectrum yet are mutually dependent. Movement allows one to exploit the effects of enemy fire. Simultaneously, firing at the enemy when on the offensive and moving increases the devastation of maneuver warfare.16

Although the strength of martial arts styles such as drunken style kung-fu and capoeira lies in the practitioner’s ability to confuse the adversary, how the opponent carries himself and the use of little gestures and idiosyncrasies can tell you a lot about his strategy. Sun Tzu said, “If the enemy is far away and challenges you to do battle, he wants you to advance.”17 In a sparring match, you might interpret the opponent’s enticing gesture or wave with his hand as cockiness, as an invitation to come closer and show him “what you’ve got.” But his true intent is to unbalance you mentally and create a favorable opportunity for throwing a perfectly timed strike to your jaw and knock you out. According to Sun Tzu, the opponent would be engaging in good strategy, because all warfare is based on deception and one should “[h]old out baits to lure the enemy.” The question for you is not so much about whether or not you will take the bait, but whether you can use good strategy to outwit the adversary. Sun Tzu also said that if the opponent “is arrogant, try to encourage his egotism.”18 If you decide to respond to his enticing gesture and move forward, be prepared for the trump card he has hidden in his sleeve. To thwart the attack, you must stay a step ahead in planning. You might try moving forward at a slight angle instead of straight in, maintaining a superior position away from his line of power.

Humility, in contrast to over-confidence, can also be used deceptively in the martial arts. When an argument is escalating and the situation is becoming hostile, you might try to bring the opponent’s guard down by offering an apology and explaining that you do not want to fight. The idea is to “make the enemy see [your] strengths as weaknesses and [your] weaknesses as strengths.”19 But if he underestimates your intentions and is mentally underprepared, he will be taught a hard lesson when you reach out to shake his hand in friendly apology and instead grab his fingers in a brutal joint lock.

In Western martial arts that rely on the direct approach to battle, one can try deceiving the opponent by faking a strike to one area and attacking another, or pretending to engage in a stand-up fight when the goal is a ground fight. Many fighters are head hunters. Try throwing multiple strikes to the opponent’s head while pressing the attack. When you have trained him to defend his head, launch a roundhouse kick to his thigh area. Or better still if you are skilled at the ground game and he is not, shoot for his lower legs and take him down. You can also use deception within a move. Instead of standing toe-to-toe with the opponent and counterstriking, drop to the ground the moment he lands a strike to your body to create the impression that his strike did damage. As Sun Tzu said, simulate disorder where there is order. Simultaneously grab his legs and take him to the ground with you.

If you are skilled at the ground game, it may benefit you to take the opponent down. You can increase your chances of victory by using techniques intended to deceive him prior to the takedown. (Image source: The U.S. Army, Wikimedia Commons)

Yet a way to enjoy a relative strength advantage is by dividing the enemy forces. Sun Tzu’s saying, “The place of battle must not be made known to the enemy,”20 demonstrates the importance of splitting the hostile force. By not announcing one’s intentions, one can compel the enemy to defend many places simultaneously, preventing him from consolidating his strength against the critical point:

If I am able to determine the enemy’s dispositions while, at the same time, I conceal my own, then I can concentrate my forces and his must be divided. And if I concentrate while he divides, I can use my entire strength to attack a fraction of his. Therefore, I will be numerically superior.21

A strategy focusing on dividing the enemy forces enables the martial artist to appear superior when he is inferior in stature or strength. Sun Tzu and Clausewitz agreed that the best way to accomplish this is by attacking the opponent’s center of gravity; his balance point, because this will naturally split his forces and ability to counterattack.22 A practitioner of drunken kung-fu excels at evasive tactics and has naturally trained to achieve superb balance particularly in unusual postures. If you were to fight this martial artist, how would you go about attacking his center of gravity? Although Sun Tzu and Clausewitz agreed that defense is the stronger form of war (as will be discussed in greater detail in chapter 7) in the sense that the defensive position requires less energy expenditure and therefore benefits the weaker army, they clearly understood that defense is only viable if used as a springboard for offense. Although you can deter an attack for some time and wait for the most opportune moment to counterattack, you cannot win a fight through defense alone. You will defeat a person who is master at evasion by preventing him from evading your attack, for example, by cornering him or luring him into close range. The fact that evasion works best from long range reinforces the importance of knowing the terrain. When fighting a drunken style kung-fu practitioner, if possible, choose an arena that does not give him the space he needs to execute evasive movement. Likewise, if your opponent is an exceptionally strong long range kicker, try attacking his center of gravity from close range where he cannot use a kick against you. Or take his ground and destroy his foundation with kicks to his legs.

The traditional martial arts are not so much about body size and physical strength as about the ability to deliver the greatest impact to the target in the shortest amount of time, or what Sun Tzu referred to as consolidation of strength against the critical point, and which demonstrates the pragmatic approach he took to warfare. Precise blows to vulnerable targets such as nerve centers have the capacity to split the opposing forces and momentarily paralyze the adversary or even end the fight. A precise strike to a nerve center on the forearm, for example, can get a knife-wielding adversary to drop his weapon instantly.

Early Ming Dynasty meridian chart from Hua Shou (acupuncture). The concept of dim mak, or the death touch, might have originated in Chinese medicine. A complete understanding of the human body’s weaknesses and strengths would potentially allow a skilled martial artist to strike a pressure point, split and conquer the opposing force, and defeat a stronger adversary. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Other options for splitting the hostile force involve decreasing the opponent’s defensive capability by attacking separate targets in rapid succession. For example, strike to the head and then kick to the legs. When his focus shifts to defending his legs, move in and elbow him in the face. Then drop your weight, grab his legs, and take his foundation. The practitioner of mixed martial arts tends to view the opponent’s whole body as a target: the ankles, legs, torso, arms, wrists, neck, and head. He must be in exceptional physical shape when fighting others of the same discipline, and must have enough understanding of human anatomy to know which targets are the most vulnerable and deserve the greatest protection. For example, he must keep his guard up to protect his head and his chin down to protect his neck and throat. He must keep his elbows tight to his body to protect his ribs and kidneys. And he must avoid inadvertently extending his arms toward the adversary to protect his elbows and wrists.

One can also split the hostile force by attacking multiple times to the same target such as the head or outer thigh area, and create sensory overload, preventing the opponent from counterstriking. A sustained effort in firepower, or the continuous bombardment of the adversary, will force him to focus on defense, may unbalance him, and will generally cause chaos and disorientation. The moment he extends his arm to counter, he will expose a vulnerable target. When related to the sport aspects of the fighting arts, a competitor can gain points by demonstrating to the judges that he has the capacity to dominate the fight through a number of successive blows.

An important ingredient in Clausewitz’s theory of war is fighting a decisive battle. In other words, the battle has to lead to a decision; it is a means to an end rather than an end in itself, with each blow bringing you a step closer to the objective. Although decisive battle implies pitting strength against strength in accord with the armies of ancient Greece and Rome, within the decisive battle are elements of movement and deception designed to weaken a superior enemy. Movement, as a part of strategy, does not concern itself directly with the use of military forces in combat, but with the object of war. The purpose is to position so that one can better utilize the tactics at one’s disposal, press the attack, and destroy the enemy forces.

In order to fully utilize movement and truly benefit from surprise, however, one must attack where the enemy is unprepared. This requires the indirect approach to warfare and the ability to hold the initiative. Furthermore, surprise may not be possible if you are the defender, for example, in a street fight or home robbery. On the strategic level, the successful use of surprise gives you a relative strength advantage and increases your fighting spirit. While the element of surprise is invaluable for gaining a strategic advantage that assists an army in amassing power against the decisive point, Clausewitz acknowledged that deception is difficult to use with success. The army must also be ready to act rapidly once surprise is achieved.

While strategy requires sufficient planning that can inadvertently be revealed to the enemy prior to the fight, tactics happen at the spur of the moment and limit the adversary’s ability to predict which move to defend against next. The fact that warfare in Clausewitz’s time was waged with modern equipment in mass armies, with access to long range weapons and firepower, might be a reason why he did not emphasize deception on the strategic level like Sun Tzu did, but considered it principally an element of tactics. “[S]urprise lies at the root of all operations without exception,” he suggested, “though in widely varying degrees depending on the nature and circumstances of the operation.”23 However, he recognized that what surprise gains on the tactical level in the form of “easy execution, it loses in the efficacy,” because “the greater the efficacy the greater always the difficulty of execution.” Ultimately, good tactics lead to victory, but you will generally not achieve great results with a small surprise on the tactical level or score complete victory with a single tactical move.24

Unlike Sun Tzu, Clausewitz also made a clear distinction between strategic defense and strategic offense. If somebody breaks into your home and you defend yourself by harming or killing the adversary, you are on the strategic defensive no matter how aggressive your conduct. The person instigating the fight by attempting to rob you is on the strategic offensive, even if he is unable to do you harm. This is one reason why the martial artist can legitimately employ ruthless techniques aimed to maim or kill the adversary while claiming to engage in defense and not offense. Although holding back a strategic reserve is senseless because the war can be lost in the first battle, the object should be to minimize losses until you find an opportunity to turn the situation to your advantage. By contrast, holding back a tactical reserve (conserving your energy) is vital to success.25

Finally, the social, political, and economic conditions of a state (or individual fighter) must be considered when determining strategy, because these conditions often influence motivation and initiative. Clausewitz’s famous dictum that war is simply a continuation of policy (political intercourse) by other means suggests in part that people relate to each other through violence, and war (or combat) is the means or instrument by which one furthers one’s political aim. Consider a person getting robbed at gun point. Should he hand over the wallet and car keys and be thankful that he managed to escape with his life intact? Or should he play hardball and offer the robber some snotty comment in return for the intrusion? What if he has just completed a course in haganah, an Israeli street fighting system that drills students in practical gun disarming techniques and other methods of self-defense? How does it change his leverage in this particular “political” situation?

A strategy that is successful in one battle may not be similarly successful in another under a different set of social and political circumstances. Ideally, a skilled martial artist considers the mentality, intelligence, will, emotions, and other psychological factors of each potential belligerent. He or she is aware of the full “political” situation, is able to discriminate and make wise choices, and knows exactly how much he can achieve on his road to victory with the means at his disposal. Ultimately, however, he cannot escape the uncertainty of battle and the crippling effects of friction.