CHAPTER 6

DESTROYING THE

ENEMY FORCE

“He who understands how to fight in accordance with the strength of antagonistic forces will be victorious.”

— Sun Tzu

“All war supposes human weakness, and against that it is directed.”

— Carl von Clausewitz

Battle should be entered from a position of strength (physical size, muscular strength, well fed and rested, and with good morale and courage). In offense and defense, the techniques the martial artist uses should inflict damage that ultimately leads to the destruction of the opposing force. In accordance with Sun Tzu’s analogy, “The army will be like throwing a stone against an egg,”1 a strike or kick should be aimed at a target that is inherently weak, such as the eyes, throat, or groin. Using a strong weapon to defend against a weaker weapon, for example, by jamming the elbow into an adversary’s front or roundhouse kick rather than blocking with the hand or forearm allows the martial artist to practice this concept also in defense.

Ancient Chinese military writings speak of how victory should come quickly, because the longer the military experience the greater the risk of disaster. Failing to destroy the opposing force can give the enemy the power to rise again even if the initial attack proved successful. Destructive capabilities are further increased by taking advantage of opportune moments in the fight and preventing the opponent from counterstriking, or as Sun Tzu reminded us, “When the enemy presents an opportunity, speedily take advantage of it.”2 His work on maneuver warfare illustrates the importance of positioning for proper use of strength. A speedy attack against the enemy’s flanks or rear has potentially greater destructive capability than a head-on clash with the opposing force. If possible, do not allow an enemy to get behind you or to your weak side: “After crossing swamps and wetlands, strive to quickly get through them, and do not linger,” position so that you have “dangerous ground in front, and safe ground to the back.”3

Superior positioning is good strategy for any fighter, but particularly for he who is physically weaker or numerically inferior to the opponent. Superior positioning enables the martial artist to take the enemy by surprise, using speed and aggression when aiming for the total destruction of his forces. While meeting the enemy in direct attack can gain one access to centerline targets such as the groin, solar plexus, and throat, he who positions away from the enemy’s line of power generally enjoys a relative strength advantage without risking immediate retaliation. Positioning to the side, for example, opens up targets to his outside thigh area and knee, kidney, and jaw. The relative superiority of a physically stronger opponent can thus be compromised by forcing him to guard against attacks from unexpected directions. In the same vein, Sun Tzu realized that attacking the enemy’s strategy and foiling his plans before attacking his army would weaken him significantly, making the physical destruction of his forces easier. Ultimately, success requires intricate knowledge of the enemy and oneself.

The physical destruction of the enemy forces is but half of the aim of the offensively minded fighter. The other half entails moral destruction. He who loses his fighting spirit can no longer engage in battle with hope of victory. Herein lies the importance of helping the adversary lose the battle gracefully. A revealing example from history might be Germany’s loss in World War I versus Japan’s loss in World War II. The Versailles Treaty signed at the conclusion of World War I between Germany and the Allied Powers called for Germany to accept full responsibility for the war and pay enormous reparations, a demand which gravely humiliated the German people and prompted them to rise again. By contrast, the Japanese population was quicker to accept their unconditional surrender to the Allies at the conclusion of World War II. The promise that they could retain their emperor as a living symbol of Japan also helped them retain their pride as a people.

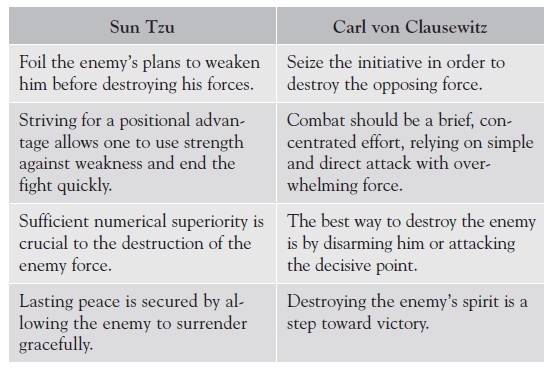

Like Sun Tzu, Carl von Clausewitz believed that combat should be a brief, concentrated effort in order to minimize losses. But, unlike Sun Tzu, he favored direct attack against the opposing force much like a boxer relying on a knockout to win the fight. He agreed that numerical superiority (physical strength) and the concentration of force against the critical point, or what he called “the hub of all power and movement,” is crucial to the destruction of the enemy force.4 “The best strategy,” he said, “is always to be very strong [italics in the original], first generally then at the decisive point.”5 While numerical superiority comes in degrees and is not necessarily decisive, he acknowledged that a numerically inferior combatant emerging victorious against much greater odds constitutes the exception rather than the rule.

Furthermore, Clausewitz demonstrated little room for benevolence in his analysis of war. He did not consider winning without bloodshed a realistic option, as reinforced through his statement that “[t]he destruction of the enemy’s army is the key to his defeat.”6 The successful combatant thus seizes the initiative and destroys the opposing force while time is on his side:

Let us not hear of Generals who conquer without bloodshed. If a bloody slaughter is a horrible sight, then that is a ground for paying more respect to War, but not for making the sword we wear blunter and blunter by degrees from feelings of humanity, until someone steps in with one that is sharp and lops off the arm from our body.7

The conduct of warfare can be divided into a number of principles, with the destruction of the enemy’s military capacity of principal importance. Although diplomatic means can help maintain peace, they cannot necessarily secure peace. This chapter discusses the benefits of numerical superiority, the strengths of the offensive weapons, and the need for speed and aggression aimed at undermining the enemy’s physical prowess and fighting spirit.

Key Points: Destroying the Enemy Force

Numerical superiority or physical strength in the martial arts is only one factor of importance when securing victory, albeit a significant one. Sun Tzu recognized its importance by suggesting that a numerical superiority of five to one is necessary in order to attack the enemy successfully.8 But he also acknowledged the limitations of numerical superiority. “In war, numbers alone confer no advantage,” he said. Instead, you must “estimate the enemy situation correctly and then concentrate your strength to overcome the enemy.”9 He further noted that troops who are sick or weary from hardship can be defeated even if numerically superior. Ideally, battle should be fought on your terms where you choose the time and place of the engagement, thereby increasing your relative strength advantage: “[H]e who occupies the field of battle first and awaits his enemy is at ease, and he who comes later to the scene and rushes into the fight is weary.”10

Clausewitz agreed that superiority in numbers is crucial and, like Sun Tzu, advocated striking the enemy with a force that is significantly stronger. He further stressed the importance of combining numerical superiority with attack directed at the decisive point, because such a strategy can effectively “be a counterpoise to all the other cooperating circumstances.”11 For example, even the martial artist who is physically superior to his enemy might consider an attack directed against the eyes or ears, because an enemy who cannot see cannot fight, and an enemy who cannot maintain balance cannot fight. (The inner ears contain the sensory organs for balance, and to this effect they constitute the “hub of all movement.”) On the other hand, a martial artist who lacks the physical strength to attack with overwhelming force, and who is not in position to attack a critical target, must decide whether or not he can defeat the opposition through other means such as deception or positioning. Consider two boxers circling each other in a ring. The tactically dominant boxer strives to retain the superior position by avoiding moves that might get him cornered or placed with his back to the ropes.

Furthermore, as discussed in chapter 5, combat is a struggle of will. In one of his works from 1805, Clausewitz stated that a chief rule of politics is never to be helpless, and the objective of imposing one’s will on the enemy can most readily be achieved by disarming him.12 He who is unable to use his weapons—be it guns, knives, arms, or legs—will experience a sudden loss of confidence. A martial artist engaged in single man combat can achieve this goal by dislocating a joint or destroying the ligaments in his adversary’s shoulder, elbow, or knee. The physical destruction of the adversary’s weapons renders him incapable of resisting and counterstriking. But if he cannot be defeated outright, an option is to destroy his forces one at a time until he loses the strength and will to continue.

While aiming for the destruction of the enemy forces, there is simultaneously a second element of combat that must not be forgotten: the safety and preservation of one’s own forces. Little is gained if both belligerents perish in the fight. Self-preservation, as a negative element of combat because the enemy cannot be conquered through defense alone, thus complements the positive action of attack.

Brazilian Jiu-jitsu offers some good examples of how the skilled fighter can progressively work his way closer to victory, through intimate familiarity with the human anatomy and a clear understanding of the enemy’s capabilities. (Image source: Brian A. Goyak, Wikimedia Commons)

In unarmed hand-to-hand combat, attacking the enemy with full intent of destroying his forces without risking a broken bone or damaged ligament in the process requires a gradual strengthening of your weapons. Many martial arts focus on conditioning the hands, feet, elbows, shins, and skull by striking a variety of training apparatus. For example, you may start by striking a focus mitt or bag bare fisted, and after a few weeks of training graduate to striking harder targets such as a makiwara board (a padded striking board or post with a rough surface). As your hands and feet become conditioned to the impact, you may progress further by pounding your fists into pellets or sand, and finally by breaking boards, bricks, or ice. Critics of breaking view this practice as nothing but showmanship, claiming that it has little martial arts value. But it behooves one to remember that the ability to break a board or brick without fear of damaging the hand or foot gives the martial artist confidence to strike an adversary with full force in a real fight and persevere.

The ability to break wood, ice, or bricks enhances the martial artist’s confidence in his abilities to throw a strong strike without incurring an injury. (Image source: James B. Hoke, Wikimedia Commons)

Muay Thai, an aggressive martial art from Thailand that focuses on doing maximum damage to an opponent, exposes the combatants’ bodies to tremendous physical abuse. Also referred to as the art of eight limbs, the Muay Thai fighter’s use of hands, feet, elbows, and knees makes him an extremely dangerous weapon at medium and close combat range. Thought to have originated nearly two thousand years ago as a hand-to-hand combat art, and later employed to battle the Burmese, Thailand’s traditional enemy, Muay Thai was used in conjunction with weapons such as the curved knife and bladed staff for the purpose of demolishing the adversary. For example, a Muay Thai fighter might throw a front kick to momentarily halt a weapon attack, and then seize the initiative by counterattacking with a knife or staff. Note the similarity in concept to Western medieval swordsmanship, where the knight would use a kick to keep his opponent at bay if the distance proved unsuitable for a strike with the longsword. Before becoming a modern sport, Muay Thai fighters would wrap their hands in hemp ropes or strips of cotton for the dual purpose of protecting their hands against injury while inflicting wounds on the adversary. Sometimes, fragments of glass would be glued to the ropes.

The Muay Thai fighter trains for speed, accuracy, and power. Speed allows him to seize the initiative; accuracy enables him to attack the weakest part of the opponent’s anatomy with a strong weapon; and power ends the fight. The elbows and knees are particularly feared weapons because their small impact surfaces give them sharp, penetrating power. Elbows and knees prove effective at close range, where they have the capacity to neutralize the power of an adversary well-versed in long range strikes and kicks. While the elbow derives its power from the full rotation of the body and, aimed at the jaw or temple, can end the fight instantly, the power of the knee is increased by grabbing an opponent around the neck and pulling him forward and into the strike without rotating the body. Knees are used as preparatory weapons to wear the opponent down and open him to a knockout.

The Muay Thai kick thrown to the legs may be one of the most devastating weapons invented in unarmed combat. The relentless pounding of the opponent’s outside thigh area is aimed at the physical destruction of his foundation and thus his ability to remain in the battle. To fully understand the value of this strategy, consider how all styles of martial arts focus on building a strong stance for the purpose of generating powerful strikes and kicks. A Muay Thai kick with the shin aimed at the opponent’s foundation can generate enough force to break bones, drop the opponent to the ground, and cause the total destruction of his combat capability. If thrown to the body, a kick with the shin can easily break a rib and damage the internal organs, ending the fight instantly.

Siamese King Naresuan fighting the Burmese crown prince at the battle of Yuthahatthi in 1593 CE. Muay Thai was developed from a hand-to-hand weapon art employed by the Thais against their traditional Burmese enemy. (Image source: Heinrich Damm, Wikimedia Commons)

A Muay Thai boxer who has strengthened his shins through repeated training can kick with full intent of doing damage without fear of injury, and without wearing protective equipment. This is important because fear of injury tends to have a negative psychological effect on the fighter and can cause him to relinquish the initiative. Furthermore, since Muay Thai was developed for the battlefield and not the ring, every move has to count. Defensive blocks are viewed as offensive strikes. The elbows, which are strong, hard, and pointed, make excellent blocking weapons. An elbow block aimed at the opponent’s front or roundhouse kick ideally has enough power to shatter his shin bone. Since the traditional goal of the Muay Thai fighter is to destroy the enemy force, injuries in sports competition remain high. Muay Thai fighters who start training at a young age normally retire from competition by their mid-twenties.

Practitioners of the Japanese fighting styles may be particularly noteworthy for their ability to destroy the enemy force. Many Japanese martial arts encourage the practitioners to train bare fisted to harden their weapons and gain the confidence they need to take a strike as well as dish it out. Those training for combat rather than point sparring learn to throw several strikes and kicks in succession, relentlessly pounding the opponent into submission. Breaking boards, bricks, and ice, although inanimate objects, conditions the fighter to strike with penetrating power. Suppleness and flexibility are also crucial to injury avoidance. The fighter who is tense cannot respond to a threat as quickly as he who is supple, and can be controlled easier by the opponent. Flexibility further enables the martial artist to use his hands and feet interchangeably, for example, by kicking the opponent in the head from close range, thus increasing his destructive capability.

Practitioners of kyokushin karate, founded by master Masutatsu (Mas) Oyama (1923-1994 CE), train hard in full contact fighting, often without gloves and other protective equipment to achieve an unbreakable fighting spirit and a tough body that can endure severe punishment. Each attack is done with full intent of doing damage. Typical techniques include the fist impacting with the knuckles of the first two fingers, the hand sword impacting with the outer edge of the hand, the elbow and forearm, and the knife edge, ball, heel, and instep of the foot. Emphasis is placed on mental conditioning. Since the mind leads the body, he whose spirit is broken cannot command his body in battle and is thus technically destroyed. The skilled kyokushin practitioner can eliminate distracting thoughts of pain and death and focus only on achieving the victory.

Shotokan karate, founded by Gichin Funakoshi (1868-1957 CE) with roots in Okinawa, is a martial art that likewise excels in destructive capability. The deep stances of shotokan facilitate strength and power with emphasis on linear moves and economy of motion by taking the most direct route to the target. Typical techniques include reverse punches, front kicks, and sweeps, with kicks aimed primarily below the waist. The combat philosophy behind the art is “to kill with one blow.”13 Each technique is therefore developed for maximum penetrative power.

However, the Korean martial arts may prove particularly interesting to study for their spectacular techniques aimed at the destruction of the enemy force. In addition to employing hard throws that will immediately destroy the enemy’s capacity to retaliate, hapkido is highly effective for destroying the adversary’s weapons and combat efficiency. Through a combination of hard strikes, violent throws, and brutal joint locks, the hapkido practitioner does every move with full intent of ending the fight quickly. Should you find yourself on the receiving end of a hapkido joint lock, you will know beyond a shadow of a doubt that, in an environment away from the training hall where you are not afforded the luxury of tapping out, the tiniest technique progression will incapacitate you immediately.

Success in hapkido depends on accuracy in strikes, kicks, and joint manipulation techniques. A single blow directed at a vulnerable target, such as the opponent’s upper chest or heart, has the capacity to drop him to the ground instantly. The mindset is that you may not get a second chance, so the first defensive move against the adversary’s attack must be done with maximum force. A kick to dislodge a weapon from his hand, for example, must be thrown with accuracy in order to have the intended effect. The hapkido practitioner must also have the technical expertise to proceed with a joint lock without delay. Techniques designed to flow with the opponent’s momentum rely on quick and sharp reversals of direction. A forceful break of the adversary’s wrist will result in immediate destruction of his combat capability. Catching the leg of a kicking opponent must likewise be done with speed and full intent of doing damage. A takedown followed by a dislocation of the knee joint would afford the adversary no opportunity to struggle against the technique.

Taking the opponent off balance, for example, by catching his leg as he kicks, followed by a knee dislocation technique will destroy his foundation as well as his weapon (his leg). (Image source: Nathan Hall, Wikimedia Commons)

Like hapkido, taekwondo is an extremely punishing martial art. Although Olympic style taekwondo is a modern invention, traditional taekwondo has ancient origins and was developed for combat to the death. Hand techniques are used on occasion, but practitioners rely primarily on a large arsenal of high and low kicks and can deliver blows with tremendous destructive power. Kicks can be thrown to any target but are primarily aimed at the adversary’s head and neck. Speed is the key to power and minimizes target exposure particularly in spinning techniques. The thrust of the hip in combination with the rotation of the body generates a force that will drop the adversary and end the fight instantly. Keeping the arms and legs close to the body throughout the spin naturally facilitates speed and aids the martial artist with balance. Like the spin kick, the front kick is effective because of the momentum created by the large leg muscles. Front kicks are often used in combination where the first kick draws the desired reaction and the second kick ends the fight. For example, a front kick delivered to a low target such as the body or groin will stun the adversary and either force him to step back or lean forward. The next kick is then thrown to the head to knock him out. Although the full sequence of techniques that destroys the enemy’s combat capability includes only two kicks thrown in rapid succession, an opponent will unlikely survive the attack intact.

The taekwondo axe kick, dropping from above the head straight down into the target with the aid of gravity, likewise relies on the large muscles in the leg for power and has the capacity to end the fight in a knockout, broken bones, or shock. An axe kick landing on the shoulder can incapacitate the opponent’s arm by breaking the clavicle, resulting in the destruction of that weapon. Impacting the target with the heel of the foot further concentrates the force over a small surface area, resulting in maximum damage with minimum effort. As a dynamic art that relies on relentless attacks to defeat the enemy, those facing a skilled taekwondo practitioner in battle naturally need a great deal of courage.

As demonstrated through these examples, the physical destruction of the enemy proves common in martial arts of Asian origin. The Western “way of war” adheres to many similar philosophies. Clausewitz believed that the simple and direct attack with overwhelming force is superior to any attack involving extensive maneuvering or long sequences of techniques that can easily be foiled by the enemy. If, at any time during the execution of a complex maneuver, one is subjected to friction or chance, improvisation may not be possible. Thus, the initiative typically rests with the aggressive fighter who uses direct attack and simplicity over complexity. Economy of motion, Clausewitz informed us, is the key to success: “Our opinion is not on that account that the simple blow is the best, but that we must not lift the arm too far for the time given to strike.”14

For example, as demonstrated in small circle jujitsu developed in Hawaii by Wally Jay, functionality with respect to smooth transitioning from one technique to another facilitates economy of motion in accordance with the principle of never lifting “the arm too far...” Most importantly, mastering technique transitions enables the practitioner to control the opponent and be prepared for unforeseen changes. Success depends on exerting continuous pain, communicating to the adversary that a break or joint dislocation is imminent.15 Small circle jujitsu is primarily about controlling the opponent from a standing position; the goal is not to go to the ground with him. A relative strength advantage can be gained by attacking a weakness in his anatomy. For example, a strike can seldom be caught in midair successfully, but a block against an opponent’s punch can open an opportunity for a joint lock technique, as can any grab against the upper body. If the opponent reaches out to push, the small circle jujutsu practitioner can take advantage of the motion by pivoting his upper body to the side, placing the opponent’s hand within easy reach for a counter-technique. A quick trap of the adversary’s hand will stabilize the motion, allowing the practitioner to proceed with a finger lock. The pain is instantaneous, giving the adversary no chance to counter the move. He has but one choice: to submit or risk incapacitation.

Several distinct Western combat arts also stress the destruction of the enemy force. Savate, developed in France in the early 1800s for use on the streets as a means of survival, relies primarily on kicks to stop an attacker; although, strikes when used often result in knockout. The savate fighter prefers kicks to strikes because street fights in early nineteenth century France had taught the fighters that the legs were capable of delivering blows far more devastating than punches. Since savate was practiced in abundance in Marseille, a port town in southern France, it is speculated that it drew its techniques from a mix of Asian fighting styles brought to France from sailors returning from Asia, coupled with Basque fighting styles as a result of the Basque influence in southern France.16 A distinguishing characteristic of savate is the use of reinforced shoes similar to wrestling shoes. (Savate means “old shoe” or “wooden shoe.”)

Savate, also known as French foot fighting, is a Western combat art with emphasis on kicking skills. Note the shoes that are typically worn in training and competition. (Image source: Daniel, Wikimedia Commons)

Geared toward full contact fighting with focus on hard training and sparring, and kicks to keep the brawler at a distance, savate is unique among street fighting styles. The savate practitioner’s emphasis on techniques considered essential in street fights, while ignoring forms practice and spirituality, makes him a tough opponent in a battle that has as its goal to incapacitate the enemy. Accuracy in strikes and kicks is naturally important. Savate proved particularly useful among sailors fighting onboard ships on a rolling sea, where ropes and other structures could be used to help the practitioner maintain balance when kicking. For example, a savate fighter delivering a spin kick to his adversary’s head would use the deck of the ship for support, by dropping down with his hands almost as if doing a cartwheel. (Note the similarity in concept to the kicks of capoeira.)

As a combat art used by the French police and military elite, savate kicks are aimed at low, medium, or high targets, and are also used to compromise an adversary’s balance. Although the savate fighter frequently throws kicks to the head because of the vulnerability of this target and the likelihood that it will end the fight, a kick to the knee of an advancing opponent will destroy his leg and thus his capacity to retaliate. The stop-kick, thrown like a front kick but with the toes turned outward from the centerline, proves particularly practical because it can be driven through the target with the fighter’s full weight behind it, yet requires no rotation of the body. Economy of motion is therefore preserved. Impacting with the bottom of the foot rather than the ball, heel, or toes further minimizes the risk of missing the target. A stop-kick aimed at the thigh just above the knee, hyper-extending the adversary’s leg, will stop his advance instantly.

Sweeps, a trademark of savate, are set up with aggressive punches, driving the opponent to the rear and compromising his balance. Since the sweep itself will not destroy the enemy force, it must be delivered to a sensitive target such as the Achilles tendon. Preferably, both legs should be swept simultaneously. An added advantage of the sweep is that an adversary who is taken to the ground repeatedly must expend a great deal of energy getting back to his feet and will eventually tire and become useless in combat. In the same vein, kicks thrown to the arms will not only injure the opponent, but tire him and render him incapable of continued offense. However, the spirit of the competitive savate fighter tells him to reject defeat. As long as his legs are intact, he can fight even if his arms are damaged.

To further emphasize the importance the savate practitioner places on kicking, punches in competition must be thrown in combination with kicks. For example, jabs can be used to set up the finishing kick by prompting the opponent to bring his hands up to defend against a strike aimed at his face. A quick follow-up roundhouse kick with the ball of the foot, or with the toes if wearing shoes, can easily break the opponent’s ribs. The same kick aimed at an organ such as the liver or kidney can drop the opponent to the ground. Driving the knuckles of the hand into the adversary’s face followed by a kick to his midsection or lower ribs with the tip of a hard shoe would likely render him incapable of continued fighting.17

If one is unable to completely overthrow the enemy or destroy his forces, what options remain? Although some martial artists believe that the benevolent fighter should only do the amount of damage needed to secure safety, Clausewitz recognized that in an activity as dangerous as war, the desire to appear benevolent can backfire, giving the enemy the power to rise again. He said, “[c]ombat is the only effective force in war; its aim is to destroy the enemy’s forces as a means to a further end.”18 However, he acknowledged that a conflict does not have to be “mutual murder.” Victory can also be achieved by “killing the enemy’s spirit rather than his men.”19 Like Sun Tzu, he spoke of the importance of taking the enemy by surprise. The relative strength advantage gained through unorthodox fighting techniques can have the effect of breaking the opponent’s morale and fighting spirit. In fact, killing his spirit may be a surer way to victory, because an enemy who acknowledges defeat has taken the first step toward constructing a lasting peace. This is an area where Asian and Western military theories converge. According to the Chinese military classic, The Methods of the Ssu-Ma, physical strength allows one to endure the hardships of battle, but spirit helps one secure the victory.20 Allowing the enemy to surrender gracefully is of great importance, because without the option of surrender an enemy will be compelled to fight to the death, prolonging the battle and potentially increasing the losses for all involved.

To fully appreciate Sun Tzu and Clausewitz, however, one must guard against taking their statements out of context. While winning without bloodshed is ideal, as a participant in China’s long and brutal war history, Sun Tzu understood that blood would likely be shed before the battle was over. Clausewitz, by contrast, while defining war as physical battle, acknowledged that some conflicts can be resolved through diplomatic means. Only if one wants to overthrow the enemy’s military powers must there be a physical engagement ending in the destruction of his military capability. The participants in battle can also take an offensive or defensive stand depending on the objective: to destroy the enemy force or defend against such destruction; to take territory or defend territory. The offensive or defensive nature of the objective will determine how one approaches combat. For example, a martial artist may be fighting a purely defensive battle with the aim of driving the enemy away. The total destruction of his forces may not be necessary if an aggressive display of mental superiority will convince him to back down and leave the property.

However, in conflicts where combat does not actually take place, the idea of combat must still be at the heart of each belligerent. While delay, caution, and diplomacy can prove more valuable than dashing headfirst into battle, objectives cannot be met unless the martial artist also projects a physical and mental readiness to engage the enemy with the aim of destroying his forces and thus his combat capability.