CHAPTER 7

STRENGTH OF THE

DEFENSIVE POSITION

“One defends when his strength is inadequate; he attacks when it is abundant.”

— Sun Tzu

“Defense is the stronger form of war.”

— Carl von Clausewitz

Military historian John Keegan argues that China has historically focused on defense and pacifist ways of war, such as caution, delay, and avoidance of battle over offense and face-to-face confrontation.1 However, as explained in The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, “Defense does not end with just the completion of the walls and the realization of solid formation. One must also preserve spirit and be prepared to await the enemy.”2 Defense works only in conjunction with offense for winning the political objective. It is relied upon when in the inferior position, because it allows the weaker fighter to preserve energy (thus, it is the stronger form of war). But defense does not imply passivity. Good defense has several aims: protect you from harm, destroy the enemy’s ability to fight by tiring him, and create an opportunity for offense.

Sun Tzu’s saying that “[t]hose skilled in defense conceal themselves in the lowest depths of the Earth,” and “[t]hose skilled in attack move in the highest reaches of the Heavens,”3 suggests that action is more heroic than non-action. Although defense without counterattack can fulfill the immediate aim of protecting one from harm, it is useless in the long run because it fails to destroy the opposing force. Like offense, and in order to serve the end goal of victory, defense must be executed with correct timing; it must interfere with the opponent’s offense and provide an opportunity to seize the initiative. Deceptive practices are particularly appropriate for the weaker fighter, because it allows him to attack when the enemy does not expect it. As underscored in the principle of nonresistance, use strength when the opponent is weak and yield when he is strong.

Unlike Sun Tzu who promoted deception aimed at increasing the relative strength of his forces, Carl von Clausewitz favored offense over defense for reaching the political objective. He who takes the initiative, he argued, will act with increased morale and can concentrate his strength against the decisive point. However, he understood that conditions favoring the opponent cannot be overcome unless action is delayed and strength shifted to the weaker or less advantaged side. The hope is that the opponent will exhaust himself prematurely. “War,” he pointed out, “begins with defense. The offensive does not lead to war unless the side which is attacked responds; this is why reciprocity is central to understanding war’s nature. The big advantage enjoyed by the defender is time.”4 Defense has a negative aim: to avoid the aggressor’s purpose. Offense, by contrast, has a positive aim; for example, to acquire treasure or force the enemy into submission. Without a reciprocal exchange of blows, however, there will be no conflict worthy of the name war, combat, or battle. It must thus be recognized that defense is not passive even though its immediate objective is. Delayed action merely prepares the defender for the counterattack. The changeover from defense to offense should happen as soon as the defender has determined that it will benefit him.

This chapter discusses the relationship between offense and defense and why defense is the stronger form of war. Although the martial artist can use defense successfully as a strategic measure to preserve or build strength, he cannot use it as a tactical measure with any degree of success. He must eventually convert defense to offense, because no battle is won through defense alone.5 Blocks, evasion, positional superiority, and deterrence are defensive means by which offense is created with the aim of winning the objective.

Key Points: Strength of the Defensive Position

We can think of defense as sitting quietly behind a wall or barrier, holding up a shield or blocking an attack. But the goal of a defensive block or parry in the martial arts is to pave the way for the counterattack by stalling the opponent’s momentum and creating an opportunity for retaliation when he is weak or unprepared. In Classical times, armies used shield walls when advancing toward the enemy on the battlefield. The shields protected against weapon attacks and allowed the bearers to force the enemy into retreat. Defense executed with correct timing thus interfered with the opponent’s offense and caused “friction” that denied him the victory. In similar fashion, a Muay Thai boxer, for example, can defend against a knee strike and cause friction by placing his hands on the opponent’s hips, preventing him from extending the hip even while his weapons remain technically intact.

In hand-to-hand combat, the fighter who has great defensive skills alongside of great endurance will likely defeat an opponent of great offensive skills but not as great endurance. Picture two boxers engaged in a bout. He who is stronger unleashes enormous offense from the start with the intent of destroying the opponent’s physical capability to fight. But the physically weaker fighter with great defensive skills covers up and is thus able to absorb the blows by taking them on nonlethal targets such as the arms. Good defense naturally requires great composure when under attack. When the attacker wears out physically, the defender retaliates with a barrage of strikes. If his timing is sound, he has a good chance of winning the fight.

Defense is also about movement and evasion. The skilled boxer uses footwork to evade an attack; he ducks and slips punches (moves his head side-to-side); he controls the center of the ring, forcing the adversary to expend energy through excessive maneuvering. Evasive movement proves particularly important to the physically weaker fighter against an aggressive opponent who presses the attack. Controlling the center of the ring allows him to funnel the opponent into a corner, limiting his mobility and power. Defensive bobbing and weaving is also beneficial because it places the boxer in a superior position toward his adversary’s side or back. The time is now ripe for counterstriking with a hook or straight strike to the head. Every time the offense-minded boxer unleashes a strike he will be punished, not by trading blow for blow, but by his opponent’s superior use of defense.

But even an exceptionally skilled boxer cannot duck and slip his way through a three-minute round without throwing a single strike and expect to win. In war, a well-entrenched defense must counter-fire at the enemy and destroy him as he is closing the distance. A purely defensive boxer might win by default, for example, if the offensive boxer accidentally twists his ankle and cannot continue the match, but this would not be viewed as a true victory and a re-match would likely be scheduled at some future date. Furthermore, the purely defensive boxer would get disqualified, because there can be no match if he does not agree to physically engage his opponent. In war, the trench might allow a weaker army to preserve strength, but the counter-blow must eventually come in order to destroy the opposition.

It is thus clear that the boxer must capitalize on defense at an opportune moment. Good defense places him at close combat range and at a superior angle away from the opponent’s line of power. Ideally, his counterstrike should come when the opponent is mentally imbalanced and needs time to regain his composure. Good defense allows the physically weaker boxer to preserve energy at a minimal cost while seizing the initiative for the counterattack. The important part to remember is that offense and defense are directed toward the same goal—victory—and attack is the “pivotal point of defense.”6

The idea that one type of warfare (defense) contains elements of the other (offense) is apparent in Asian writings. The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China discusses the integration of various counterparts of warfare, such as ch’i (indirect) and cheng (direct). For example, “some [forces] use spies to be successful; others, relying on spies, are overturned and defeated.”7 The trick is knowing when to use indirect versus direct attack; when to rely on defense versus offense, or, in some cases, how to integrate defense and offense, for example, by jamming an elbow into the opponent’s shin as defense against a roundhouse kick.

The shaolin kung-fu “splashing hands” system of fighting, so named because the movement of the hands mimic shaking off water, focuses on simultaneous defensive and offensive techniques geared toward street fighting, in addition to explosive high-speed movement such as quick shuffles to avoid the opponent’s line of power while closing the gap, and straight kicks aimed at low targets. The number of strikes delivered in rapid succession combined with the shuffle promotes deception and makes this martial art ideal for stifling the opponent’s offense. The splashing hands system relies on close range fighting coupled with checks and blocks, and the skilled practitioner seizes the initiative by making the first move, drawing a desired reaction from the adversary. When the opponent attempts to withdraw from the attack, the practitioner reverts to offense while remaining at close range, giving the adversary no opportunity to distance himself or regain his composure. Close range fighting and timing is refined through two-person drills performed in the training hall.8

Wing chun kung-fu likewise focuses on simultaneous defense and attack through its close range multiple strike philosophy. Deflections and evasive moves coupled with forward pressure double as offense, or at the very least pave the way for the skilled martial artist by allowing him to capitalize on a defensive move as soon as an opening appears in the adversary’s guard. Kenpo karate is yet an interesting martial art to study because it provides several demonstrations of how offense exists within defense. For example, when the opponent grabs the kenpo practitioner’s lapel, he steps back and outside of the opponent’s reach for the punch or kick that must certainly follow, simultaneously pinning the opponent’s hand to his lapel and striking upward against the elbow of his outstretched arm. The mere fact that the kenpo practitioner stepped back in defense, however, forced the opponent’s arm to extend, which assisted the kenpo practitioner’s offensive strike against the elbow. Defense was thus converted to offense. For further analysis of the interaction between defense and offense, consider how kata in most styles of karate begin with a defensive technique and, following the defense, immediately implements an offensive technique to demonstrate that defense by itself is not enough to win the fight. Many of the offensive techniques are maiming blows aimed at a vital target such as a joint or nerve center.

As demonstrated through these examples, combat is the continual interaction between opposing forces with an escalation in power resulting in one side emerging victorious. Since it includes elements of attack and defense and both belligerents strive to conquer, there is no true equilibrium between forces. Rather, defense is the immediate aim of the weaker fighter in order to ensure his survival. In other words, he who chooses to suspend action does so not as an act of cowardly submission, but with the knowledge that it will bring him favors. Consider in the grappling arts how a simple cover-up can help one preserve strength while waiting for an opportunity to counterattack. The guard position (on your back with the opponent between your legs) proves effective because of the limits it places on the opponent’s movement and ability to attack. Options for a counterattack include an arm bar, a choke, and a variety of wrist and finger holds. For example, the defender can use his legs which are to the outside of the opponent’s body to apply a triangle choke. Mixed martial arts have gained enormous popularity through the display of good strategy and tactics in offense and defense.

Brazilian Jiu-jitsu with its arsenal of chokes, wrist and arm locks, and leg and ankle locks may prove particularly interesting when studying the strength of the defensive position. An opportunity for a counterattack will be present the moment either fighter extends a limb toward the other. Since he who controls the other holds the initiative also in defense, the goal of the Brazilian Jiu-jitsu practitioner is to seize control and impose his will on the opponent, preventing him from executing his techniques as intended. For example, an opponent on his back or side can be controlled with an arm bar. By pushing his weight into an opponent on his knees, the Brazilian Jiujitsu fighter can control the movement of the adversary’s hip and virtually immobilize him, thus gaining the option of moving to a stronger position for the counterattack. How successful he is has to do with his ability to recognize the opponent’s weaknesses in each position he assumes, and taking action against them. Chokes, for example, can be applied from the front, rear, and side, in figure-four fashion, or as cross-collar chokes. Having intimate knowledge of the workings of the human body aids the Brazilian Jiu-jitsu fighter in the anticipation of the next move, and helps him lure the opponent into inadvertently placing himself in a position of defeat.

Relying on defense as the stronger form of war also means that one must exercise patience, waiting for the enemy to make a mistake that can be exploited. Brazilian Jiu-jitsu is ideal for turning the opponent’s power against him through its many leverage concepts. The supine position, which is considered weak in most martial arts, can be an advantage in Brazilian Jiu-jitsu. When an opportunity to convert to offense arises, for example, when a straddling opponent makes a mistake that momentarily jeopardizes his balance, the skilled Brazilian Jiu-jitsu fighter can topple him, grab an extended limb, and execute a lock against the elbow, shoulder, or ankle.

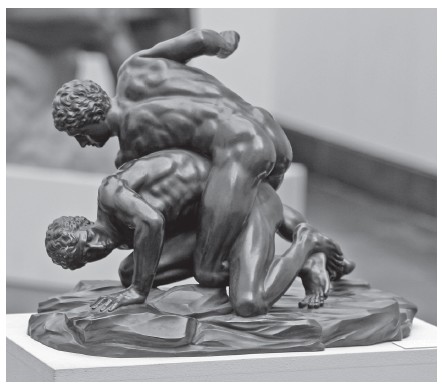

Wrestlers are known for their knowledge of how to manipulate the balance of an opponent from the defensive position, as demonstrated in the techniques used by these ancient pankrationists. Note the lock around the ankle. (Image source: Matthias Kabel, Wikimedia Commons)

As summarized in these examples, although defense is typically assumed by the weaker or physically inferior fighter, it is the stronger form of war because it allows him to preserve energy and counterattack at a time of his choosing. The martial arts require courage and the summoning of one’s total physical capacity. As further demonstrated in the Ultimate Fighting Championship, combat does not consist of a single decisive blow, but of a succession of blows where the weapons—arms, legs, body, and mind—are coordinated for maximum power and effect. The first strike merely creates a favorable condition for each successive strike. (The mind is not a weapon per se but refers to a rational element comprised of good judgment. A fighter with a clear mind can see “through the confusion of [battle] to its core and then [take] decisive action.”9)

Both Sun Tzu and Clausewitz stressed the importance of defeating the opponent quickly in order to reach the political objective without incurring excessive losses. Although Communist leader and political theorist Mao Tse-tung (1893-1976 CE) favored protracted war, the Chinese army has historically valued speed over duration.10 No action should be suspended in war. However, as observed in the early days of the Ultimate Fighting Championship when matches did not have time limits, deception and the defensive position were used by the physically inferior fighter as strategic choices leading to victory with some matches lasting in excess of thirty minutes. The grappling arts, pioneered by the Gracie clan in the 1990s, demonstrate how a protracted battle can bring victory over a physically stronger opponent if your endurance and patience are strong enough. Eventually, you must fire back, however, or the opposing force will remain intact, break through your defenses, and emerge victorious.

Moreover, while the attacker typically holds the advantage of the initiative in any battle, the defender holds the advantage of surprise. Once the defender decides to counterattack, the attacker will be forced to go on the defensive, particularly if he is tired after having thrown a barrage of blows. The fight has now turned in favor of the defender. Thus, before choosing to fight a protracted battle, you must decide whether it is better waiting to launch your counterattack or taking advantage of the moment. If waiting turns the battle in favor of your opponent, it is better to take advantage of the moment and launch a forceful attack. However, if waiting allows you to preserve strength and emerge the superior fighter, this may be the better strategy.

Even martial artists who emphasize defense when entering a confrontation generally acknowledge the value of offense once it has been determined that their strength is adequate. Defense is also used to gain an edge after enticing the attacker to make the first move. How do you create this advantage? One way is by using the blocking weapon as a weapon of offense, for example, by striking a pressure point simultaneous to blocking the opponent’s strike. Another way is by redirecting the strike through the use of minimal force, disrupting the opponent’s timing and power and providing openings for the counterattack. Rather than giving up the initiative, you take it through defensive action by creating a favorable opportunity that brings you closer to victory.11

Hapkido practitioners typically demonstrate how to neutralize a threat through defensive action while causing “disorientation with minimal effort followed by a disabling attack.”12 The encounter starts with defense but ends with offense. The hapkido practitioner wins by exploiting the opponent’s strength and counterstriking to a vital point. Although he who is strong in offense can take advantage of the defender by pressing the attack, he will likely expose a weakness sometime during the encounter. Consider also a sparring match where one of the participants relies on short bursts of strikes or kicks to overwhelm his opponent before falling back on foot-work and movement to replenish his forces. The best time to start a counterattack is the moment the adversary reverts to defense, but before he has regained his composure and strength.

It has been said that offense is the best defense. Many martial arts and systems of self-defense focus on striking a vital point simultaneous with the defensive move. For example, an elbow strike to the sternum of an aggressive opponent can effectively aid an unbalancing technique. (Image source: Ken Melton, Wikimedia Commons)

Aikido, by contrast, was developed based on the premise that it is a strictly defensive art, using neither strikes nor kicks to counter an opponent’s attack. How does aikido function in relation to the idea that offense is the best defense and that one cannot win a fight through passive defense alone? The skilled aikido practitioner uses the attacker’s momentum, evading the attack through superior timing rather than blocking it, and executing dynamic throws that will ideally send the adversary flying several feet away. Properly performed, aikido allows one to preserve energy against a stronger opponent while forcing him to expend energy. By adapting to the aggressor’s offense, the aikido practitioner neutralizes the attack, often without inflicting permanent damage on the adversary. Like other defensive martial arts, aikido has a negative aim: to avoid the aggressor’s purpose. But unlike many other defensive arts, it has no positive aim of destroying the enemy forces. The hope is that the aggressor will realize the folly of his ways and pursue a path to peace instead.

Aikido further advocates evasive moves for the purpose of decreasing the risk of sustaining an injury. This is particularly important if the enemy is wielding a weapon. The greater the force is behind the opponent’s attack, the greater the momentum of the aikido practitioner’s evasive move. For example, the motion of a front kick can be redirected with a sweeping vertical downward parry of the hand. The attack line is changed and energy preserved. As the opponent’s momentum carries him forward, he becomes ripe for an unbalancing move. For example, the aikido practitioner might place his forearm across the opponent’s upper body, directing him to the ground through a rearward sweeping spiral. The opponent will be perplexed that his kick missed the target and will attempt to kick again. But by then he has lost the initiative. As long as the aikido practitioner occupies the center of the circle, he can control the opponent’s motion by going with it or reversing its direction. Reversing direction when controlling the center takes relatively little energy, which is why the move is so devastating to an opponent who occupies the outer edge of the circle. By continuing the motion or reversing its direction, the defender will constantly be evading the opponent’s attempts to renew the attack. He will thus gain the initiative and ability to control the action without ever launching an offensive technique.

The aikido practitioner can likewise defend against a punch thrown to the head by controlling the attack line, redirecting the strike with a parry upward along his centerline while allowing the momentum of the strike to continue. He would now be in position to retaliate with offense; for example, with a knife hand strike to the opponent’s neck. Or he might choose the gentler way and capitalize on the opponent’s momentum by placing his forearm against the opponent’s neck, controlling the center of the circle, and ending the fight with a throw that sends the adversary several feet away. Either way, the first defensive principle of aikido is avoidance of the attack and controlling the enemy by using correct and precisely timed techniques rather than pitting strength against strength.

However, a problem with a purely defensive art is that the opponent will likely refuse to accept defeat at the first parry or evasive move. A skilled aikido practitioner stays mentally ahead of his adversary, relying on mushin, or absence of thought as discussed in chapter 1. Absence of thought entails total awareness of the situation and is achieved through extensive experience in one’s martial art. When the aikido practitioner achieves this state of mind after much practice, he can accept each attack as it comes toward him and with small and fluid movements capitalize on the opponent’s momentum. The skilled aikido practitioner does not allow his energy to clash with the opponent; he does not violate the yin and yang by creating the condition for double-weightedness (exerting yang forces simultaneously with the opponent). Instead, when the opponent absorbs the momentum of his own attack, his focus will split with his main concern retaining balance. His own aggression will thus act as the agent of his defeat. Controlling the attack line and the center of the circle also allows the aikido practitioner to guide the offensive limb into a joint control technique with a number of options at his disposal: take the adversary to the ground, damage the joint, or force him to submit through pain compliance.

Aikido is a strictly defensive martial art that relies on controlling the center of the action, using the opponent’s energy against him often through a weakness in his anatomy such as the wrist. Once the attack has been neutralized, the aikido practitioner can force the adversary to submit through pain compliance without actually damaging the joint. (Image source: Magyar Balazs, Wikimedia Commons)

A person engaged in a modern street encounter away from the training hall might use a defensive technique to momentarily stall the adversary’s advance. His next step might be to launch a counterattack that will eliminate the threat. For example, he might start by bringing his arms up in front of his face to block a strike. The moment he blocks or avoids the blow, he reverts to offense by kicking the adversary’s groin or elbowing him in the face. Failing to revert to offense will give the opponent the initiative, enabling him to break through the defensive barrier. Again, good defense must contain an element of offense. Preferably, the initial defensive technique should be instinctive, giving you momentary safety even in ambush. When you have gained a better sense of the nature of the threat, you can proceed with offensive action.

Battle can also be fought defensively in strategic terms, but offensively in tactical terms. This relationship between offense and defense can be observed in a self-defense situation; for example, a burglary of your home in the middle of the night. The burglar breaking into your home is invading your territory and is therefore on the strategic offensive. By contrast, you, the homeowner, are on the strategic defensive because you did not initiate the conflict. However, the moment you reach for the gun in the dresser drawer, the knife in the kitchen, or the phone in the office for the purpose of calling for help, you are on the tactical offensive. It is not absolutely necessary to aim for the total destruction of the enemy in every fight. Although the negative element of delayed action is not immediately as effective as the positive element of action, it might have a good success rate over time. When the opponent’s energy expenditure is far greater than he expected, you may find a way to beat him physically or get him to agree to a peaceful settlement of your differences. The enemy might also choose to give up when he finds that far more effort is required to remain in the fight than what he had anticipated. But, by the same token, passive resistance will not destroy the enemy forces. The risk therefore exists that the enemy will attack you again at some future date.

How far can you take Clausewitz’s tenet that defense is the stronger form or war? Since wars should be won as quickly as possible, action should not be suspended. However, if the enemy refuses to engage in the hope of finding a more favorable time for attack, the war will be suspended. But it can only be suspended by one side. Both sides would not agree to suspension, because then it would be peace and not war. If one side chooses to suspend the action, it does so in order to seek favors. The other side must then act without delay. By contrast, stalemates occur not because both sides agree to suspend the action but because the forces are evenly matched, or because the weaker force relies on defense as the stronger form of war and prolongs the battle. Thus, true equilibrium between the forces is never a part of warfare. Rather, both sides strive to conquer, and action will continue toward the climax until one side emerges victorious. Since war is divided into attack and defense, if you chose to suspend the action, your opponent would naturally prefer that you attack, and vice versa.

For further analysis, consider how you would classify a demonstration of power without actually exchanging blows? Is it defense or offense? Is it the stronger form of war? If you display a weapon or demonstrate your martial arts skills to a group of people, your reputation alone might communicate that you are a dangerous person, thus decreasing the risk that you will be attacked. You have now taken a defensive position through a display of offense. But, according to Clausewitz, this is not war, because war is about physical action and not deterrence.13 Clausewitz further proposed that one should assume the defensive position only when one does not have the ability to seize the initiative. Defense is the stronger form of war only because it allows the weaker force to conserve strength while waiting for a good time to launch a counterattack. If you display your strength in front of others, you must also be physically and mentally ready to use it if push comes to shove. Morals aside, the person with superior strength should seek the initiative rather than focus on defense.

The physical display of power is evident in this ancient Roman mosaic picturing two boxers. Although a display of power can be a deterrent to battle, it must be supported by physical capability in order to serve a defensive purpose. Moreover, in a martial arts contest it is assumed that the fighters want to engage each other in physical battle. (Image source: AlMare, Wikimedia Commons)

As discussed previously, and in contrast to Clausewitz, Sun Tzu advocated winning without engaging in combat. But how is this achieved? Should one publicly display one’s forces as deterrence to battle, engage in diplomacy, or turn the other cheek? How would you classify a preemptive attack? Is it offense or defense? Is it the stronger form of war? Can you justify it morally through the perception of threat alone? Sun Tzu agreed that, although a public display of force may be used as a deterrent to conflict, the option to engage in combat must remain open in order for it to classify as combat or martial arts. The fact that your opponent knows that you have studied the martial arts but does not know how skilled you are can deter a fight altogether, or it can buy you time that allows you to preserve your forces until you can retake the initiative. Sun Tzu also emphasized deception as a defensive measure that would allow you to seize the initiative: Appear weak when you are strong and strong when you are weak.

As demonstrated through the examples in this chapter, although defense is the stronger form of war when fighting from a physically inferior position because it is generally “easier to hold ground than to take it,”14 it is impossible to rely on defense alone. Doing so would mean that only one side is relying on offense, and there can be no war unless both sides exchange blows. In short, defense must have purpose; defense must be offensive, for example, through surprise or superior positioning. From a psychological perspective, offense is often the stronger form of war. Troops are generally more motivated to fight when they feel they are actively doing something. It is also true that the advantage generally lies with the attacker or the side who takes the initiative. But, while the offensive position ensures victory, as described in T’ai Kung’s Six Secret Teachings, a defensive posture that is solid can accomplish its intended purpose and help the defender win the political objective over time. Once the decision is made to fight, one must be victorious, and offense and defense must play mutually interactive roles.15

Furthermore, the genius of military leadership lies in a combination of instinct and experience, or the ability to realize when defense has outlived its useful life. When you are pressed on your right, when your center is giving way, when you are overcome by the enemy forces, when it is impossible to move... it is either attack now or die. He who chooses to delay the fight by assuming the defensive position does so because his physical capacity is inferior to the enemy and not because he treasures a long war.