CHAPTER 8

FAILURE

“Know your enemy and know yourself, and in a hundred battles you will never be in peril.”

— Sun Tzu

“The knowledge in war is very simple, but not, at the same time, very easy.”

— Carl von Clausewitz

Sun Tzu recognized several human characteristics that prove detrimental to the soldier on the field of battle. A reckless fighter, for example, will be at greater risk of injury and death than a thoughtful fighter. Simultaneously, while he who is too impulsive can be provoked to commit an act that he will come to regret or that will jeopardize his safety, he who is overly afraid of death will be too cautious to prove effective; he will hesitate and forego the chance to score a victory. He further strove for maximum gain with minimum risk. As explored previously, conflicts should be ended quickly by making decisions based on knowing the enemy and yourself, and by using deception to turn the enemy’s strength against him.

Carl von Clausewitz, by contrast, viewed boldness superior to timidity. His ideal way of war emphasized strength at the decisive point and the destruction of the enemy forces even at the risk of loss. Which approach is better? Although boldness will trump timidity which “implies a loss of equilibrium,” a calculated caution should be part of the strategic plan.1 A commander’s intellect can lead an army in the proper direction and minimize downfalls. Failure, however, is a great teacher. As will be discussed in more detail in chapter 10, understanding that winning matters also in friendly competition will prompt one to study failure.

Analyzing how a technique can go wrong will bring insights into success and failure and empower you to make practical adjustments to your training regimen. Conducting a detailed study of failure will teach you about the steps required to avoid failure while broadening your understanding of techniques that work well or less well under a range of circumstances. Studying failure further opens the door to knowing your enemy and yourself, which Sun Tzu regarded as the cornerstone of success. Although success cannot be guaranteed no matter how well-planned your strategy, Clausewitz’s On War likewise demonstrates that when the causes of failure are properly studied, the enlightened scholar can take action and decrease the risk of falling victim to chance.

The question that must be asked is what you are truly capable of achieving at any particular stage of the fight. Henry Ford (1863-1947 CE), American industrialist and founder of the Ford Motor Company, said that failure is the opportunity to begin again, more intelligently. Although a particularly disastrous failure might not afford one the opportunity to begin again, in general, failure, as miserable as it is, is a sobering experience that provides insights into one’s strengths and weaknesses, prompting one to become a better and more intelligent martial artist. This chapter explores the common causes of failure with an eye toward knowing the enemy and yourself by identifying the essential elements of the different fighting styles.

Key Points: Failure

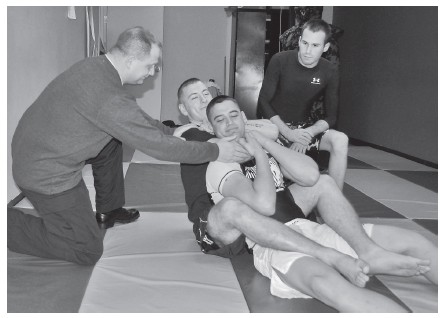

Many martial arts techniques work well in the training hall because your practice partner has been conditioned to attack and stage a reaction to an attack in a premeditated way. For example, consider how an aikido practitioner might fare if the attack happens quicker than anticipated and he is unprepared to sidestep the strike and flow with the motion. Would an attacker who had never practiced aikido really be sent flying as far away and as smoothly as is often observed in the training hall? Studying failure will teach you why proper timing of your defense to the opponent’s attack is crucial. In the same vein, although Sun Tzu underscored the importance of choosing your ground wisely, this is not always possible. A martial artist who is sitting down when suddenly attacked may be physically unable to sidestep the strike and flow with the motion. Whether or not you score the victory thus depends on a number of uncontrolled circumstances, including individual skill and the ability of the enemy to utilize the environment to his advantage.

Experimenting with techniques designed to end a fight, under the guidance of a qualified instructor, will teach the practitioner what it takes to defeat an uncooperative opponent. (Image source: Kaylee LaRocque, Wikimedia Commons)

Friction, as Clausewitz called it, becomes particularly evident when a martial artist of one style meets a martial artist of another style in battle. For example, a tactic popular with the wing chun kung-fu practitioner involves fighting from close range with the aim of tying up the adversary’s arms or splitting his focus with a barrage of short range strikes. If the opponent is a skilled boxer whose strength rests with the use of his hands, an attack against the hands (the boxer’s center of gravity) may be the determining factor that ends the fight. But the opposite outcome is also possible. A boxer with a considerable physical strength and reach advantage might throw a knockout punch before the wing chun practitioner has a chance to position inside of the boxer’s range of power and use the tactical moves called for by his martial art.

The particular techniques used to defeat the adversary further differ between martial arts. Some arts focus exceedingly on stand-up fighting, others on grappling. Some arts are predominantly striking arts, others kicking arts. Some arts are hard styles relying on direct attack and quick knockout, others are soft styles relying on flowing motion and extensive maneuvering. Sun Tzu stated that victory comes to those who know when they can or cannot fight: “If I know our troops can attack, but do not know the enemy cannot be attacked, it is only halfway to victory. If I know the enemy can be attacked, but do not realize our troops cannot attack, it is only halfway to victory.”2 Knowing yourself means that you clearly understand your physical and mental limitations. If you are under-trained in certain aspects of the fighting arts, you should avoid fighting from that perspective. For example, a great karate fighter who has never trained in a grappling art would be wise to know his limitations and strive to end the fight before it goes to the ground. Knowing your enemy means that you clearly understand his strengths and weaknesses. Fighting a superb high kicker should be avoided at distances that allow him to capitalize on his kicks. Moving to close range and sweeping his supporting foot might be an option that eliminates his kicking ability. But this tactic represents the ideal way of war and is not necessarily an accurate representation of how the battle will ultimately go down.

No matter how extensive your training has been, it is highly improbable that you will be skilled in all styles of martial arts. If your focus is stand-up fighting, superior grappling skills may take years to acquire. However, basic techniques relevant to combat, such as the benefits of a stable stance and ability to utilize movement to your advantage, may take only a few months to acquire and would increase your chances of surviving a ground fight as long as you also possess the mental qualities that make up a good fighter: endurance, perseverance, courage, and a desire to seize the initiative and win. Crucial to success is the understanding that an opponent who has as his goal to take you down must first close the distance regardless of which specific technique he uses for the takedown (throw, sweep, joint lock, etc.) Ideally, you might use footwork to set up a long range kick from an unexpected angle. A skilled taekwondo practitioner, for example, would use his kicking strengths and time a well-placed kick to his adversary’s head, knocking him out the moment he attempts to close the distance for a takedown.

Defense, as we have learned, is the stronger form of war, and an opponent who uses defense skillfully can interfere with your combat plan, making your attack fail even if you are the physically stronger fighter. How do you counter good defense? When your attempt to pound the opponent into submission on the ground fails, you must have the physical skill and mental composure to adapt, for example, by recognizing an opportunity to apply a joint control hold. But, as Clausewitz stated, although the knowledge is very simple, it is at the same time not very easy. Knowing what needs to be done will not help you win the war, unless you also possess the relevant skills. What should be recognized from Sun Tzu’s and Clausewitz’s writings is that the discourse of combat, how we talk about it, is the ideal way of war but not how battle ultimately unfolds. We can take all of Sun Tzu’s and Clausewitz’s advice to heart and still fail. We may also well understand their analyses, yet be unable to apply the insights because we are not in position to choose the time and place of battle.

|

When pounding an opponent into submission fails, a skilled grappler can detect opportunities for adaptation and offset the effects of friction by making a move against a weak part of the anatomy, as demonstrated by this soldier defeating his opponent with an arm bar. (Image source: Lynn Murillo, Wiki-media Commons) |

Sun Tzu and Clausewitz taught us that the nature of combat or the underlying principles remain constant. It matters little who you are, what part of the world you are from, or what styles of martial arts you have studied because human nature does not change. We can only work within the range of human anatomy and human emotions. For example, taking an adversary to the ground requires that you can manipulate his balance. Whether you do so by sweeping his leg, grabbing and throwing him to the ground, or using a lock against his wrist or neck depends on which art you have studied. But the underlying principle of destroying his foundation remains constant. Friction and the uncertainty of battle likewise apply to both belligerents regardless of which style you have studied. Human emotions such as anger or fear of failure will likewise strike all participants of battle. The best you can do is to minimize losses by educating yourself about the physical and mental state of your opponent and yourself, and by practicing your martial art with the intent of analyzing the common causes of failure.

Weapon practice may prove exceptionally valuable in this regard because it teaches the martial artist that defeat resulting in the total destruction of his forces can be final. While an empty hand strike to a nonlethal target such as the arm can be forgiving, this is not necessarily true with a weapon strike. A blow with a staff or cut with a knife can prove permanently disabling no matter where it lands. Weapons also tend to neutralize the strength advantage of an empty-handed fighter. Training with weapons, even if one does not intend to carry a weapon, is invaluable for understanding the importance of precision and timing. The great Japanese swordsman Miyamoto Musashi reminded us that, “[w]hen one understands the use of weapons, he can use any weapon in accordance with the time and circumstances.”3

Kobudo (ancient way to stop war), an Okinawan martial art employing the staff as one of several weapons (staff, sai, tonfa, kama, and nunchaku), was used to fight the samurai in the invasion of the islands in 1609 CE. Practicing with a weapon, which is essentially an extension of the martial artist’s arm, aids the development of precision in unarmed combat and therefore helps minimize failure under stress when fine motor skills tend to deteriorate. Furthermore, kata or forms are frequently practiced in the martial arts as a way to enhance confidence through muscle memory. A major benefit derived from kata practice is the control of rhythm, or the ability to exercise power at the appropriate time. Confusing the opponent and creating a sense of unpredictability by breaking his rhythm aids the martial artist who must fight from a position of numerical inferiority.

Weapons are invaluable for teaching respect for combat and reminding the practitioner that a single blow can prove fatal. (Image source: Blmurch, Wikimedia Commons)

Kobudo forms with the staff employ many power moves in combination with strikes (pokes) to specific targets. Each strike and move is emphasized to instill skill and precision in offense, defense, and movement, thus minimizing the risk of failing to defend and counter another weapon-wielding fighter. Kobudo forms differ from the flashy musical kata that have become popular in competition and modern weapon demonstrations. The stress is not on showmanship but on practicality, always by understanding the dangers of facing an adversary wielding a weapon. Sun Tzu’s principle of ending the fight quickly applies, as does Clausewitz’s principle of minimizing friction by resorting to straight and direct moves rather than complex maneuvers.

We have now discussed a few options for surviving a fight against an opponent who is skilled in a martial art different from the one you have studied. But what can you do when fighting an opponent who is skilled in the same art as yours and the battle goes sour? Sun Tzu wrote the Art of War based on China’s history of fighting an enemy of similar cultural biases, and could therefore outline precise principles of fighting. He underscored that when two fighters of equal strength meet in battle, he with the greater command of strategic skill (cunning, surprise, attacking the enemy’s plans before attacking his army) will generally prevail. For example, a Muay Thai boxer facing another Muay Thai boxer in the ring knows in advance that he will encounter specific techniques such as elbows and knees, leg kicks, and takedowns, but will not encounter grappling techniques in a ground battle. He must therefore rely on strategic skill to beat his opponent. A Muay Thai fighter who fails in the ring does so primarily because he is weaker or less experienced than his opponent, or because he enters the fight low on confidence. A Brazilian Jiu-jitsu fighter facing another Brazilian Jiu-jitsu fighter likewise knows that he will encounter many techniques specific to grappling.

However, when the Ultimate Fighting Championship was instituted it was with the intent of pitting one style of martial art against another to “test” which style was superior when fighters were forced out of their comfort zones. When a Muay Thai champion meets a Brazilian Jiu-jitsu champion in the ring, assuming that neither fighter possesses any noteworthy skills in the art of the other, an element of unpredictability is brought to the action. Furthermore, away from the competition arena, the reality of war is that we cannot precisely know the fighting skills of our opponent. Although we can take measures that will decrease the risk of failure by understanding ourselves and our enemy, we cannot completely eliminate the element of friction. However, depending on the society in which you live, certain techniques can be expected and the basic use of fists and feet differs not much from one fighting style to another. Even street brawlers with no martial arts training become predictable to some extent, because human nature mandates the use of our fists to pound an opponent into submission.

Other reasons why one may fail in combat include a lack of training or poor judgment. Although Sun Tzu rated numerical superiority highly, he recognized that in the reality of combat you may not have the option of choosing your fights and must revert to a strategy that increases your strength by weakening your opponent’s, for example, by dividing his forces. Many traditional Asian martial arts, as well as Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, excel at this concept, which is why smaller or physically weaker fighters can defeat bigger or stronger opponents. Adaptability is the key along with repetitious training for the development of muscle memory. Although specific techniques and defenses may lead to failure when a sudden change occurs within the attack, constant repetition of techniques with a partner brings confidence and ability to recognize and preempt an imminent attack that you may otherwise have overlooked. As a guide to the principles of combat, Sun Tzu’s Art of War recommends seizing the initiative to offset the damaging effects of friction, for example, through a preemptive attack from an unexpected angle that further allows you to retain full focus and control of the fight. Yizhan, the idea of fighting a just war under the guise of a defensive posture, further warrants the use of a preemptive attack.4

As explored in chapter 3, practicing specific defenses to specific attacks further helps the martial artist eliminate excessive thought that leads to dangerous pauses in the middle of the action. As reinforced by the pragmatist Miyamoto Musashi, success comes by defeating the enemy at the start of the action, “so that he cannot rise again to the attack.”5 Every cut, even the way you grip a weapon, must be decisive and done with a resolute spirit.6 The greater your ability to eliminate excessive thought, the greater your focus: “Whatever attitude you are in, do not be conscious of making the attitude; think only of cutting.”7

Although the implementation of Sun Tzu’s and Clausewitz’s advice leads to risk reduction and increases the chance of scoring a victory, it does not guarantee victory. How well one does in battle has to do to some extent with the enemy’s skill and fighting style. The combat capabilities of the opponent are difficult to measure and will fall outside of your control until you have taken some action to incapacitate him, which is why Sun Tzu placed particular weight on knowing the enemy before engaging him in battle. It naturally follows that unpredictability, such as broken rhythm, is of great value in the art of war. Unpredictability in technique can also give you a strength advantage by splitting the opponent’s focus and dividing his forces. However, a weakness of Sun Tzu’s teachings is that they fail to mention that neither side holds monopoly on surprise and deception.

Fighter surprising his opponent by aggressively pressing the attack. Using the same style martial art as your opponent does not guarantee knowledge of his tactics or strategy, nor does knowledge guarantee successful action. Neither fighter enjoys monopoly on surprise. (Image source: Indrek Galatin, Wikimedia Commons)

Although the martial arts are numerous and encompass many variations, a good fighting art relies on some basic principles that, once learned, enable the practitioner to execute techniques also when the stress level is high and therefore reduce the risk of failure. Krav maga, for example, excels at eliminating unnecessary thought and keeping techniques simple yet effective. But even in arts that stress the use of complex moves, the reliance on principles rather than specific techniques helps one reduce the risk of failure, for example, by pressing the attack, disturbing the adversary’s balance, attacking weak targets in his anatomy, using deception and surprise, attacking from unexpected angles, and preserving energy through good defense.

Furthermore, the adversary may attack armed or unarmed. He may use several tactics to defeat you, for example, a strike or kick, a grab or hold, or a throw through the use of flow or superior strength. A defensive technique against an armed attacker might fail because he has an absolute strength advantage through his weapon. Drawing the attack through a sudden unexpected move (except when a gun is involved) might give you the initiative and increase your defensive capabilities. Martial arts that focus on driving the opponent to the rear, such as wing chun kung-fu, effectively eliminate the opponent’s ability to use strikes, kicks, and weapons by jeopardizing his foundation through aggressive movement. The practitioner of the fong ngan style of Chinese kung-fu likewise relies on aggressive advances inside of the opponent’s range of power to jeopardize his balance and minimize the risk of failure, by delivering low kicks to the groin or leg hooks and sweeps followed by a strike intended to end the fight.8

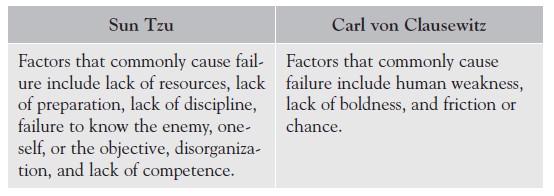

According to Sun Tzu, the factors that commonly cause failure include lack of resources, lack of preparation, lack of discipline, failure to know the enemy, oneself, or the objective, disorganization, and lack of competence. Clausewitz listed human weakness, lack of boldness, and friction or chance. Specializing in training maneuvers particular to your martial art helps you seize the initiative and reduce the time it takes to react to a perceived threat. Although you cannot always know the enemy, knowing yourself is a starting point that gives you clear insight into your capabilities. Furthermore, by understanding the specific ways in which an opponent may attack you, you have taken a step toward Sun Tzu’s dictum of knowing your opponent. Start by considering the essence of the particular martial art you are studying:

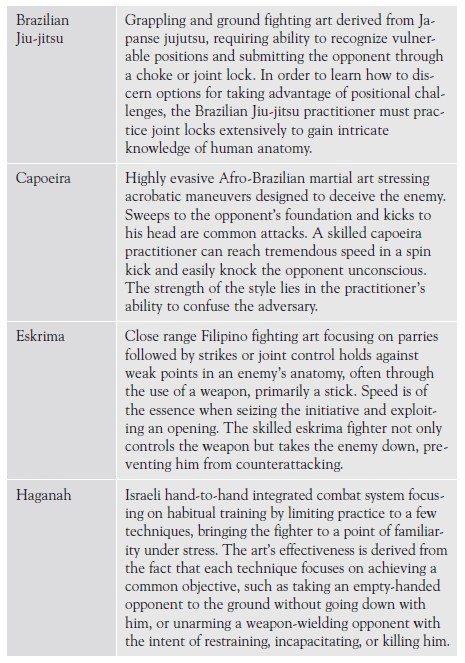

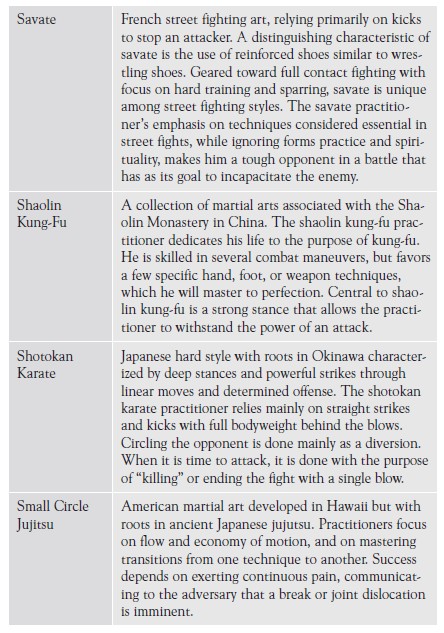

The Essence of Different Martial Styles

A difference between Sun Tzu and Clausewitz is that Sun Tzu wrote his book as a roadmap to success by stating in clear language the types of strategies and tactics the victorious army uses. The most commonly repeated advice might be, “Know your enemy and know yourself, and in a hundred battles you will never be in peril.” Clausewitz, by contrast, did not give specific advice on how to behave, but recognized the many uncertainties of war through his theory of “friction.” The principles discussed in Sun Tzu’s and Clausewitz’s books—seizing the initiative, imposing your will on the enemy, destroying his forces, correct use of defense, etc.—do not apply to any particular martial art per se. As discussed in chapter 1, the nature of fighting remains constant regardless of the art you study or the tactics (techniques) you use to defeat the adversary. Although scientific analysis of combat is necessary to broaden one’s understanding, determine an attacker’s motive, and learn the fashion in which he might attack, Sun Tzu and Clausewitz agreed that war is essentially an art and not a science. Success in war requires an ability to adapt and use artistic expression derived from much study and practice. Knowing your enemy and yourself is excellent advice. However, as Clausewitz reminded us, acting properly upon that knowledge is more difficult. As further reinforced by the ancient Chinese classic, The Methods of the Ssu-Ma, “It is not knowing what to do that is difficult; it is putting it into effect that is hard.”9

Capoeira stylists practicing their art in the streets. Understanding the essence of your martial art will assist you in decreasing the risk of failure. The strength of capoeira lies in the practitioner’s ability to evade an attack and counter with elusive sweeps or head kicks. (Image source: Aroma De Limon, Wikimedia Commons)