CHAPTER 9

MORAL QUALITY

OF COURAGE

“If a general is not courageous, he will be unable to conquer doubts or to create great plans.”

— Sun Tzu

“With uncertainty in one scale, courage and self-confidence must be thrown into the other to correct the balance.”

— Carl von Clausewitz

In face of threat, the first moral quality is courage. But since the human mind is typically more attracted to uncertainty than certainty, individual combatants tend to be unsure of their capabilities and unable to act with confidence. Good training instills the courage to face an opponent in battle and handle the various pains of combat: physical injury, fatigue, fear, and uncertainty. Courage takes two forms: acting resolutely and making major decisions responsibly when faced with personal danger. Boldness as an element of courage is based on strong situational awareness and tends to increase as a result of success, but must be tempered with judgment. The courageous combatant is therefore steadfast in battle, but employs fore-thought and intellect to avoid falling victim to impulsive or reckless actions that may ultimately lead to his downfall.

Although determination can balance the playing field for he who lacks physical size or strength, injury or public humiliation may prevent the martial artist from sustaining a high degree of courage for the duration of a fight. Knowing your enemy and yourself, as explained in chapter 8, will open the road to victory but also requires an ability to instill fear in the enemy. Comprehension of the enemy’s strategy and the capacity to convince him that potential harm may come his way will likely make him reluctant to meet you in battle. The ancient Chinese texts underscored the importance of creating a strategic position that will ultimately undermine and demoralize the enemy, or as Sun Tzu said, “[T]hose skilled in warfare move the enemy, and are not moved by the enemy.”1 Simultaneously, battle seldom goes down as originally envisioned. However, proper preparation, as reflected in the concept of ch’i, gives the soldier and martial artist the confidence he needs to fight courageously.

Since war is danger, Carl von Clausewitz agreed that the first quality the fighter must possess is courage. “War is the province of physical exertion and suffering,” he said. “In order not to be completely overcome by them, a certain strength of body and mind is required.”2 Courage involves the physical ability to engage an enemy in battle when one fully knows that one may get hurt or killed. In the martial arts, physical courage relates to the particular tactics the martial artist uses based on his strength and stamina or flexibility. If he lacks physical strength, he would rely on deception rather than insisting on meeting the enemy in pitched battle. If he lacks flexibility in the legs, he would kick low or not at all rather than attempting to kick to the head. Moral courage, by contrast, relates to mental resolve and ability to make an informed decision about the benefits of fighting. It involves boldness and daring, and as such must be tempered by judgment and self-control. Since the consequence of recklessness is injury or death, an effort to calculate the likelihood of emerging victorious must be made prior to entering battle. As explored in previous chapters, one should enter the fight from a position of strength whenever possible.

Clausewitz further believed that since each person possesses a different set of emotional qualities, it is exceedingly difficult to construct a universally valid theory for action. For example, some martial artists believe that the soft martial arts suit their personality traits better than the hard arts, and vice versa. Other factors such as the particular moment one decides to revert from defense to offense might differ between individuals, even in theoretically identical combat situations. Since combat is a product of human beings, it consists of the human emotions of anger, fear, excitement, and even joy. The answer to such questions as whether or not you should give a potential attacker your wallet when he asks for it, or fight him in physical battle instead, is therefore not immediately apparent. The moral factors of experience, morale, and intuition tend to affect war making as much as friction and chance.

This chapter examines the effects of courage on fighting and the emotional factors involved in rousing a person to action. It discusses the need for a balanced perspective between boldness and intellect to ensure the best possible outcome.

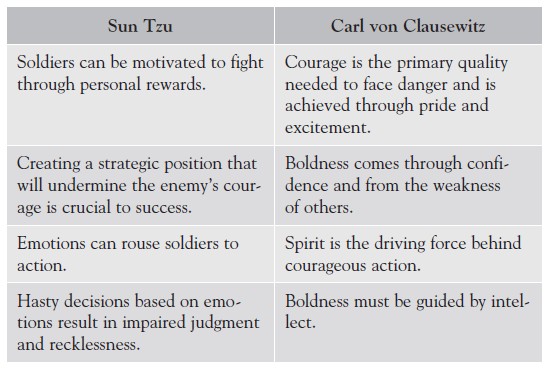

Key Points: Moral Quality of Courage

What is courage? Clausewitz described physical courage as “courage in presence of danger to the person,” and moral courage as “courage before responsibility.”3 Acts rooted in fear are generally associated with the physical preservation of one’s being and also involve escape from danger. Acts rooted in courage, by contrast, are associated with the moral preservation of one’s being (one’s reputation) and require a willingness to face an enemy in battle even when options exist for walking away.

Since war involves combat, and combat involves the physical destruction of the enemy forces and the defense of one’s own, it naturally follows that war is dangerous. Courage may therefore be the most significant of the so-called moral qualities. Moral courage is influenced by pride, patriotism, and enthusiasm, which can rouse a person to action and sometimes to recklessness and lack of judgment. Consider a martial artist tempted to show off his skills to his friends when confronted by a bully on the street. Or, as another example, consider somebody insulting your girlfriend in a bar. Would you feel obliged, as a matter of pride, to come to her defense even as you know intellectually that the better choice is to leave the bar quietly, or perhaps even offer an apology to the offender for the sake of keeping the peace? Pride, as the driving force behind action, can lead you down a path that ultimately results in physical injury to all parties involved.

Clausewitz further reminded us that “war is the province of chance,” and one cannot know with certainty whether or not one’s actions will preserve one’s safety or result in even greater physical danger.4 Learning to control the type of courage that stems from pride and enthusiasm may therefore be particularly crucial. Many martial arts teach us that he who turns his back on conflict and walks away has courage. Since people love winners and walking away implies cowardice, it does indeed require tremendous moral courage (that of good judgment) to walk away from a potential fight, particularly if the masses are watching. However, differences of opinion exist also on this issue. While Plato, a Greek philosopher of the fifth to fourth centuries BCE, defined courage as “the virtue of fleeing from an inevitable danger,”5 the Greek historian Polybius expressed in the second century BCE that soldiers regarded “their one supreme duty not to flee or leave the ranks,” and were “expected never to surrender or be captured.”6

Even if one has found peace with the decision to walk away, difficulties may arise because circumstances often demand immediate action. In other words, the opportunity to think about what to do and how to act (or not act) is simply not available. The training the martial artist receives is in part intended to help him determine which situations are worth defending with physical action and which require a more modest approach to ensure the best possible outcome. The deeper meaning of the words courtesy and self-control are worth exploring. For example, how far should you go with respect to courtesy if the favor is not returned? How much self-control should you have when your sparring partner hits too hard and bringing the matter to his attention verbally has no effect?

Moral courage is also about standing up for one’s beliefs. The difficulty lies in knowing where to draw the line. Fighters are often seen losing their temper in competition. Remember when Mike Tyson bit off Evander Holyfield’s ear in a boxing bout in 1997? Martial artists have hopefully received more training in controlling their tempers, but it is still common for emotions to flare. Consider what kind of reputation you would like to preserve for yourself, and how you can best achieve this. Your answer might help guide your actions. Furthermore, since we have a tendency “in momentary emergencies” to be “swayed more by feelings than thoughts,”7 it is prudent to rehearse the scenarios one can expect to encounter beforehand. Strategic planning brings strength of soul and resoluteness in action. A fight is typically thought as having begun when the first strike is thrown or the first move is made with the intent of throwing a strike or kick. But the skilled martial artist understands that fights begin in the mind long before the first blows are exchanged, and that a person’s intentions are often revealed through his facial expressions or general demeanor. A skilled opponent can therefore preempt any sudden move you make. When faced with an attentive enemy, you must be particularly watchful of your emotions and avoid signaling your intentions.

Maintaining composure and avoiding reckless actions when taking an unexpected kick to the head requires boldness coupled with intellect. (Image source: Indrek Galetin, Wikimedia Commons)

Like Clausewitz, who believed that pride and enthusiasm can prompt a person to act, Sun Tzu was quick to note the effects of emotions on the soldier. Soldiers, he said, are made “courageous in overcoming the enemy” by rousing them to anger.8 Like Clause-witz, he stressed that hasty decisions based on emotions rather than judgment often result in recklessness. It is better to withdraw from a challenge if possible, than to give way to the temptation to appear courageous in front of one’s peers and fight a battle that one cannot win: “If weaker numerically, be capable of withdrawing. And if in all respects unequal, be capable of eluding him [the enemy], for a small force is but booty for one more powerful if it fights recklessly.”9 Good judgment further necessitates that victory be sought but not be demanded by others. As Sun Tzu reminded us, “When the enemy presents an opportunity, [one should] speedily take advantage of it. Seize the place which the enemy values without making an appointment for battle with him.”10

Furthermore, a balance must be struck between compassion and rage. As Sun Tzu warned us, there are five qualities which are fatal in the character of a general (or, if applied to the martial arts, in the character of a martial artist). Consider the words so many of us repeat in the training hall: modesty, courtesy, integrity, self-control, perseverance, indomitable spirit. The martial artist, if reckless, can be killed; “if cowardly, captured; if quick-tempered, he can be provoked to rage and make a fool of himself; if he has too delicate a sense of honor, he can be easily insulted; if he is of a compassionate nature, you can harass him.”11 Thus, “[i]f you are not in danger, do not fight a war. For while an angered man may again be happy, and a resentful man again be pleased, a state that has perished cannot be restored, nor can the dead be brought back to life.”12

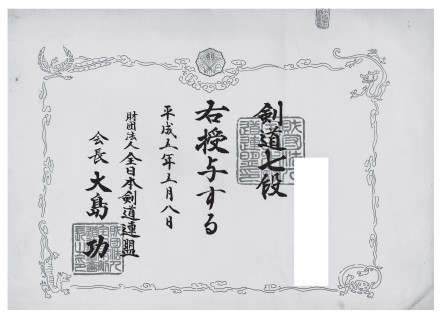

As can be deduced from these writings, the significance of the moral forces rests with the fact that it is from these that fighting spirit, the driving force behind combat, is derived. When a combatant loses his desire to carry on the battle, even if his physical forces are intact, all preplanned strategy and tactics will fall by the wayside and he will accept defeat. Victory certainly fuels the fighting spirit, but a martial artist’s true test of courage may come when he enters battle or competition willingly after having lost several fights in a row, knowing that the audience is rooting for his opponent. Although it takes extraordinary courage to overcome this reluctance to battle from the position of the underdog, it is not the same type of courage required in the defense of life. As Clausewitz reminded us, “If a young man to show his skill in horsemanship leaps across a deep cleft, then he is bold; if he makes the same leap pursued by a troop of head-chopping Janissaries [soldiers in a former elite Turkish guard] he is only resolute.”13 Thus, the difference between moral and physical courage, and why soldiers can be motivated to fight based on the promise of personal rewards for their accomplishments. “When you plunder the countryside,” Sun Tzu suggested, “divide the wealth among your troops.”14 Motivational rewards in the martial arts come in the form of trophies and belts, which translate into higher status in the training hall. Moral attributes such as wisdom, benevolence, and courage can further earn a martial artist his enemy’s respect. “Those who excel in war,” Sun Tzu said, “first cultivate their humanity and maintain their laws and institutions.”15

Belts and certificates honoring achievements can build a martial artist’s courage and act as motivators for continued training. (Image source: Yappakoredesho, Wikimedia Commons)

Along with proper etiquette comes the observance of a set of disciplined rituals, such as introducing oneself before battle or bowing to the opponent, which are meant to radiate confidence and possibly deter a potential attacker. The bow before battle is also an honorary gesture to the generations of warriors who have built the fighting arts. As explained by one master tang soo do practitioner, every bow is “a tribute to all the people who spent countless hours training and refining the art so we, their descendents, would have something of value.”16 China’s historical battles speak of how rituals gave the soldiers confidence while simultaneously instilling fear in the adversary. In the Spring and Autumn period (c. 722-481 BCE), “when the lord of Chin was advancing to attack the state of Ch’i,” the advancing general established outposts in the mountains and set out flags even in places where his army did not intend to go. The ritual communicated strength and confidence, which ultimately caused the enemy to flee.17 As reinforced by historian Victor Davis Hanson in his evaluation of ancient Greek warfare, “Conflict is often irrational in nature and more a result of strong emotions than of material need… War is sometimes won or lost as much by confidence in one’s culture as by military assets themselves.”18

However, while a martial artist may investigate and learn about the opponent’s physical capacity before battle, knowing his mental strength is more difficult. A martial artist of small stature may be targeted by a bigger person because he invokes the impression that his physical strength is inadequate. A small person must therefore demonstrate that he is unwilling to be a victim. By the same token, a person who is physically strong can be beaten if his will to fight is destroyed, for example, through fear. All one has to do is listen to some prefight interviews to learn about how full-contact fighters attempt to psych themselves up for the fight. Consider also the ring names they choose: Scorpion, Hammer, Rest in Peace, Battle Axe, etc.

Although war is about life and death, the greatest battle you fight may be the one within you. Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai by Yamamoto Tsunetomo focuses on how to develop the mental attitude necessary to face combat, and how to die gracefully and fearlessly. The samurai could fight with intensity because they faced the possibility of death daily and had been conditioned to believe it a disgrace “to die with a weapon yet undrawn.”19 From a practical military standpoint, letting go of all hope of winning allows one to enter the fight with maximum strength and focus. Embracing death, not even hoping to live, erases all regret and creates a fearsome warrior. Clausewitz agreed that boldness to proceed comes through confidence, but also “from the weakness of others.”20 Whenever a contestant performs poorly in a sparring match or martial arts competition, the confidence of his opponents tends to grow. Likewise, a contestant who performs brilliantly can cause loss of confidence in others and hinder their ability to demonstrate their skills as flawlessly as hoped. But boldness neither constitutes heroism, nor should be a “blind outburst of passion to no purpose.”21 To remain effective, it must be coupled with a reflective mind. Reenacting a fight in the training hall the way one might experience it on the battlefield will help one understand the difficulties associated with a preplanned attack.

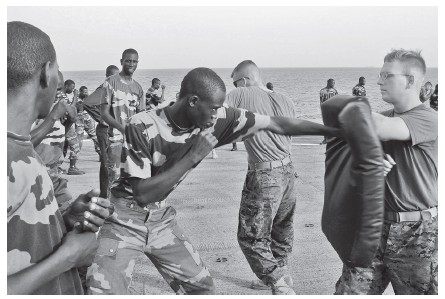

In sports competition, for example, your plan might be to take control of the fight as soon as the bell signals the start of the first round and systematically press the attack, when your opponent foils your plans only seconds into the round by landing a strike that sets your head spinning. Are your moral forces still intact, or does the blood dripping on the canvas fuel a feeling of physical and mental inferiority? In the midst of confusion, moving to action requires emotional stability, mental endurance, and an ability to know how to use the means at your disposal. It is a well-known fact that fine motor skills tend to deteriorate when a person is under stress to defend his life or well-being. This is one reason why many of the so-called reality based martial arts rely on techniques that are relatively simple to learn and use gross rather than fine motor skills. Punches and most kicks fall into the category of gross motor skills because they are drawn from intuition and rely on moves that a small child can do naturally. Wrist locks, by contrast, rely on fine motor skills because they are not intuitive but must be learned and require considerable precision to execute with success. Krav maga aims at making effective combatants within a few months of training. The same cannot be said for aikido, which may take a lifetime to learn with proficiency.22

As demonstrated by these sailors, gross motor skills, generally associated with punching and kicking, prove invaluable when trying to adjust to the chaos and uncertainty of the battlefield and will aid one in keeping one’s moral forces intact. (Image source: Joseph Lomangino, Wikimedia Commons)

Even martial artists who have endured years of training tend to revert to the natural instinctive moves of punching and kicking when taken by surprise in a threat to their life or safety. To gain the most from training, the martial artist can study the raw instinctive move of a punch or kick, and then make small adjustments to increase the power and finesse of the technique, thereby raising his confidence. Practitioners of hap gar kung-fu (see also hop gar kungfu), a no-nonsense Chinese fighting style several hundred years old, do just this, for example, by learning how to develop power from the waist while striking with simple punches that come naturally. The style retains its combat roots by focusing on damaging blows to bones and ligaments rather than on submission techniques. Take-downs and throws are done with as much force as possible and with full intent on injuring the adversary and ending the fight. The hap gar fighter tries to avoid going to the ground with his opponent. Direct attacks to vital targets—eyes, throat, groin—are emphasized, as is launching the first strike rather than reacting to the opponent’s attack. All techniques and forms are practiced as a means to an end with focus on moves that are intuitive and natural to perform by the human body, and as such contribute to the strength of one’s moral forces.23

The difficulties of acting with precision when one’s life is threatened can be offset in part by following a solid and orderly plan that brings familiarity to combat. He who faces the chaos of battle, Clausewitz writes, “must be a very extraordinary man who, under these impressions for the first time, does not lose the power of making any instantaneous decisions.”24 Sun Tzu likewise underscored the importance of order: “The battlefield may seem in confusion and chaos, but one’s array must be in good order. That will be proof against defeat.”25 Thus, as discussed in chapter 3, something should be said for habitual training, since familiarity with danger is necessary in order to produce the kind of calculated courage a person needs to swing the odds in his favor. Forms practice, although considered by some as nearly useless in the contemporary world, offers a wealth of discipline and self-control which is essential to developing boldness guided by intellect. Learning a new form is in itself a test of commitment and patience. Improving the movements in the form takes additional discipline. Forms practice helps the martial artist establish a sound mental strength foundation for continued study. Practicing a form hundreds of times also conditions the body to the strains of combat and assists muscle memory, making responses to threats more natural.

Furthermore, perseverance without losing one’s bearings when under heavy attack, and an ability to stop negative thoughts and imaginary fears from interfering, requires that one views battle from a logical perspective. The combat arts thus demand continuous training and effort to create a mental state at which the martial artist can act responsibly, unobstructed by emotions and without excessive thought. Zanshin, a term used in the Japanese martial arts to indicate awareness, is achieved through experience and produces a state of detachment in threatening situations, which further allows the practitioner to gain perspective on the situation and prevent emotions from interfering with sound judgment.26 Aikido practitioners tend to understand this concept quite well. Superior self-control allows the aikidoka to blend his strength with the opponent’s, all the while foregoing egotistical tendencies aimed at double-weightedness, or the clashing of one’s yang force with the opponent’s. The martial genius, as Clausewitz said, sees a guiding light in a cluttered environment. By contrast, he who lacks the moral quality of courage will be unable to command his forces or set his plans into action.

Going forth into battle with resoluteness and courage is thus a choice made after careful deliberation and analysis. Consider these words by the ancient Greek historian, Thucydides: “For no man comes to execute a thing with the same confidence he premeditates it. For we deliver opinions in safety, whereas in the action itself we fail through fear.”27 A trained martial artist is slow to anger and chooses his battles carefully. He ponders the dangers before taking action and does not accept a challenge based on an insult. He might have learned to press the attack, yet continuing along the current path after suffering a number of setbacks would indicate recklessness. When the strategy is faulty because the opponent is too strong or too aggressive, the tactics, the blows one uses to press the attack, will not secure the objective, which is why the most courageous action may well be to walk away while the option still exists.

Although both victors and vanquished will experience losses in war, strategic and tactical superiority coupled with courage increase the martial artist’s chances of success. Sun Tzu reminded us that when on “difficult ground, press on; in encircled ground, devise stratagems, in desperate ground, fight courageously.”28 If the fight is difficult, press forward to get through the difficulties as quickly as possible; if the enemy is numerically superior or physically stronger, look for a tactical advantage; if your life is directly threatened, there may be no choice but to fight with all the courage of your being, win or lose. However, although Sun Tzu emphasized calculated risk and Clausewitz preferred boldness in attack, a balance must be struck between caution and boldness. Caution does not imply timidity or cowardice. In fact, “deliberate caution,” Clausewitz noted, “may be considered bold in its own right and is certainly just as powerful and effective [as boldness].”29 A revealing example of caution coupled with boldness might be found in iaijutsu, or the military art of drawing the sword without telegraphing one’s intent to the opponent. Prepared to confront danger at any moment by taking advantage of tactical surprise, the Japanese swordsman exercised tremendous patience and self-control while waiting for the perfect moment to seize the initiative and defeat the enemy with a single swift cut with the sword.

How does one prevent cowardice from gaining a foothold within oneself? According to Sun Tzu, you start by prohibiting “superstitious doubts.” When you “do away with rumors; then nobody will flee even in death.”30 We have thus come full circle back to what may have been Sun Tzu’s most famous dictum: Know your enemy and yourself. Uncertainty brings fear. Start by striving to understand the enemy’s needs and how far he is willing to go to secure them. Also understand your own ability and needs and how far you are willing to go to protect them. When you know your enemy and yourself, you will project an air of confidence which may halt the enemy’s advance. In the training hall, practice the projection of your voice; learn how to say a definite no when you mean to say a definite no. The fact that many martial arts schools stress “indomitable spirit” is further testimony to the importance of strong morals in war. Next time you participate in a competition or martial arts demonstration, note how those who act as if they own the arena will draw higher scores than those who enter the competition with an uncertain or timid demeanor. The bold student may not be a better martial artist per se than his more timid counterpart, but the projection of passion and fighting spirit will communicate that he is and may swing the odds in his favor.

Thus, the power to act in the martial arts comes not only through physical strength and stamina, but from passion and ability to exercise command presence, which is further a result of having deep knowledge of your enemy, yourself, and the environment. Kungfu grandmaster Don Baird notes how you can strike and kick a 300-pound bag in the training hall or spar with your peers and maintain full confidence in your abilities. But when you enter a different environment, when you no longer wear the familiar clothing of a martial artist, when all the faces have changed, you will suddenly feel small. To build command presence even in unfamiliar places, Baird recommends training in the wilderness where you can project your power beyond yourself and the familiarity of the dojo. “I felt so small and insignificant,” recalls Baird. “A single punch, even a shout, seemed like nothing while standing in the midst of Angeles National Forest.”31 When you return to the arena of your school after such an experience, you will feel much bigger than before.

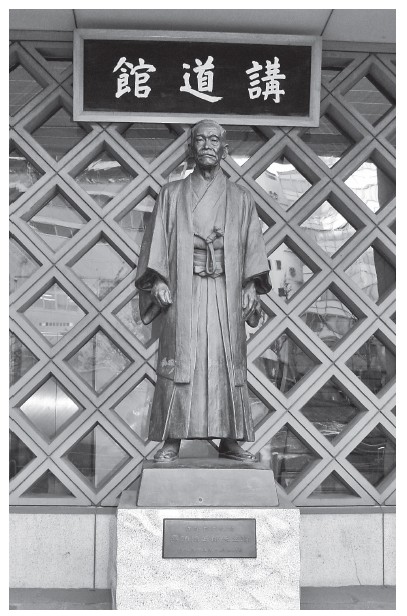

As demonstrated in this chapter, moral factors include individual personality traits such as courage and passion. How one responds to a threat is due partly to learned habits as a result of training, and partly to one’s natural inclinations and enthusiasm. Students who come to class by their own choice will generally outlast those who are motivated to come by others (children, for example, whose parents send them to class against their wishes). Those who have a natural passion for the martial arts will also spend more time in training away from the dojo and will generally excel over those whose motivation stems from outside factors. Personal motivation is one reason why it is difficult to predict the outcome of a fight based only on a person’s length of training or how many techniques he knows.

This statue of Kano Jigoro (1860-1938 CE), the founder of judo, outside the Kodokan Institute in Tokyo, Japan, stands as a reminder of the dedication and spirit required to understand combat and master a martial art. (Image source: Henrik Probell, Wikimedia Commons)

Furthermore, he who lacks passion for the martial arts will also lack creativity and fail to make the best use of the techniques he knows. Spending time outside of class, analyzing techniques and experimenting with concepts rather than simply memorizing sequences of moves, is invaluable for he who wants to excel in the combat environment. As we have learned, war is both a science and an art and pure memorization without creativity will make you fall victim to chance the moment the first “shots” are fired and your plans fall apart. As Clausewitz said, “Military activity is never directed against material force alone; it is always aimed simultaneously at the moral forces which give it life.”32

The time you spend in the training hall will lay the cornerstone for your martial arts journey; it is where you grow as a martial artist, build courage by learning about and experiencing the different elements of combat, contemplate yourself and your enemies, and find peace with your decision. Individual creativity and the moral elements of courage, willpower, and enthusiasm will fill the gaps and make the journey whole. He who is rightly prepared thus has the confidence to meet his fate in battle.