CHAPTER 10

SECURING VICTORY

“Victory is the main objective in war.”

— Sun Tzu

“The immediate object of an attack is victory.”

— Carl von Clausewitz

Victory is secured in three ways: by depriving the enemy of physical strength through death or wounds; by destroying his morale and fighting spirit; and by convincing him that the battle is not worth fighting. Although friction affects the outcome of battle, victory or defeat are not merely random happenings. You can do several things to improve your chances of emerging victorious. First, the better fighter tends to win. Who is “better”? Generally, he who has prepared well and displays a strong physical and mental resolve is the better fighter. Second, although friction can interfere with the best-laid plans, fighters who have prepared thoroughly will have a back-up plan that can minimize the effects of friction. Third, the physically strong and mentally prepared fighter can change his plans midstream to offset at least some of the effects of friction.1

Sun Tzu belonged to the school of Daoism. With respect to warfare, the ultimate goal was to restore the “cosmic harmony” through the use of the least amount of force possible. “All warfare,” he meant, “is based [less on strength than] on deceit.” Rather than fighting a pitched battle, one should confuse the enemy in order to weaken him. While force was not placed at the center of Sun Tzu’s war strategy, perhaps even more significant is the insight that the need to fight is itself an indication that one is in disharmony with the cosmic order and the perfect state of existence.2 Victory is thus attained by placing the enemy in a state of mental confusion and chaos. According to the Wei Liao-Tzu, an ancient Chinese military text, victory is gained by causing the enemy’s ch’i (spirit) to be lost and his forces to scatter.3

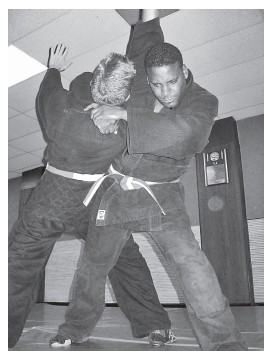

However, it is equally true that when two combatants collide in battle, the fighter who can use physical strength and size to his advantage is likely to win. As discussed previously, the art of pankration, or the game of “All Powers,” an all-encompassing system of fighting developed in ancient Greece, relies on physical strength and power over finesse and combines elements of boxing and wrestling. Techniques that do not demonstrate physical strength, such as biting and eye-gouging, are considered dishonorable. Pankrationists therefore have to be in superb physical shape (size is a plus) in order to secure victory through knockout or submission. Throughout the fight, they are left with the crucial decision of selecting the precise target that will end the match. The strategy (the combat plan) and the tactics (the specific techniques used to ensure victory) depend on each combatant’s ability to properly identify the opponent’s center of gravity (his strength, but also his critical point of vulnerability). The pankrationist uses judgment to create a situation that favors physical force.

Although one individual fighter may be better than another, questions about the alleged superiority (or the value) of one martial art over another are difficult to answer without considering the historical context under which the various fighting arts were developed. Understanding how victory is determined therefore requires a critical study of Asian and Western strategy and tactics. Whether or not you are able to claim the victory also depends on your relative superiority. You can win because you are strong, but you can also win because the opponent is weak. Had you fought on any other day against any other fighter, the outcome may well have proven less advantageous. According to Carl von Clausewitz, victory can be made more honorable by mentioning the difficulties you encountered along the way, but defeat does not become less disgraceful by bringing into light the many difficulties.4

So what is the role of physical skill in battle, and how does one determine if a martial artist is truly skillful? Is victory necessarily reliant upon skill or does it depend mainly on the circumstances surrounding the contest? Although in favor of conquering an enemy “already defeated,” Sun Tzu understood that the “expert” is not he who does the ordinary: “To foresee a victory which the ordinary man can foresee is not the acme of excellence... to distinguish between the sun and the moon is no test of vision, to hear the thunderclap is no indication of acute hearing.”5 The expert martial artist has a firm grasp of the underlying principles of battle; he is a good strategist as well as tactician. He can control the enemy, impose his will on him, and avoid fighting from an inferior position directly in the enemy’s line of power.

This chapter discusses the elements that will assist one’s pursuit of victory in reference to the concepts and principles that have been presented throughout this book, to include numerical superiority, destruction of the enemy force, and sound defensive practices. The importance of winning, the moral qualities required to achieve a lasting victory, and the preservation of peace are also considered.

Key Points: Securing Victory

Sun Tzu underscored the importance conquering “an enemy already defeated.”6 A martial artist who cannot avoid the fight altogether might attempt to defeat the opponent mentally rather than physically. Although a mental defeat can involve the use of diplomatic negotiations, this does not necessarily have to be the case. One can also use a convincing display of force to frighten the enemy into submission before blows are physically exchanged. The martial artist can practice this principle by demonstrating techniques or forms in front of a critical audience, thereby robbing any competitors of their confidence. Although cunning, surprise, and avoidance of pitched battle pitting strength against strength increase one’s chances of emerging victorious particularly when fighting an enemy that is numerically superior, note that Sun Tzu was not against the use of physical force per se. He recognized that “war was a matter of vital importance to the state; a recourse to be undertaken when other means have failed. Sun Tzu’s view of the army as ‘an instrument to deliver the coup de grace to an enemy made vulnerable by stratagem and deception,’ appears repeatedly in Chinese history.”7

Clausewitz, although focusing on the use of physical force, agreed with Sun Tzu that “the side that first introduces the element of war [through a display of force, for example] is also the side that establishes the initial laws of war,”8 and that this may ease one’s pursuit of victory or possibly lead to the avoidance of battle. For example, a martial artist who is the first contestant to enter a forms competition and whose performance is outstanding will raise the bar and thus establish “the initial laws of war” for subsequent competitors, who may have trouble outperforming him even when highly skilled.

Once Sun Tzu and Clausewitz had laid down their respective theories for success, both agreed that numerical superiority is of utmost importance, that attacking the decisive point gives one a relative strength advantage and shortens the duration of battle, and that positioning and proper use of the environment will swing the odds in one’s favor. To properly apply these ideas, the martial artist must develop a combat plan based on intimate familiarity with oneself and knowledge of the opponent’s strengths and weaknesses.

A fighter whose strengths are takedowns and submission holds must overcome the challenge of closing the distance, and must understand his opponent’s strengths and weaknesses to score a victory. A relative strength advantage can be gained through superior positioning that allows one to attack the opponent’s balance, as demonstrated in this choke/neck takedown. (Image source: Doug Meil, Wikimedia Commons)

Physical strength is a key factor deciding the victory, or as Clausewitz said, “In tactics as in strategy, superiority of numbers is the most common element in victory.”9 Since numerical superiority is so beneficial, the martial artist must not only prepare for the confrontation by building physical strength, but must be well-versed in the techniques of his art in order to offer a formidable resistance against a much stronger enemy. Sun Tzu recognized that numerical superiority can either be factual or perceived and is achieved, for example, by dividing the enemy’s strength. The martial artist can utilize this principle by attacking high and low targets in rapid succession and forcing the enemy to defend several critical points simultaneously. Options for dividing the enemy’s strength include attacking weak points in the anatomy (eyes, throat, groin, joints) from unexpected angles, or upsetting the adversary’s mental state by attacking his balance. Furthermore, control of the combat arena, and proper positioning away from the opponent’s line of power through footwork and movement, enables the martial artist to avoid a head-on clash pitting strength against strength.

Before entering battle, you must know that the advantage rests with you. Common sense plays a role, which is why we seldom see a small person initiating an attack against a much bigger person, or a single man taking on several opponents in hand-to-hand combat by choice. When you have done your prefight planning and determined that you do not have the physical strength or ability to attack the decisive point, nor the ability to use superior positioning or surprise and deception, the better option may be avoiding battle altogether. Many Asian martial arts advocate honor and integrity over winning at all cost. A fighting art’s method of employment contributes to how it is perceived. One might ask then, does the end justify the means? Sun Tzu underscored that battle should never be taken lightly. Due to its great destructive capabilities, heavy losses are likely even for victors. Whether or not one chooses to use force depends on calculations of relative power. To minimize losses, war should be viewed rationally rather than emotionally, as reflected in his statement that, “[a] government should not mobilize an army out of anger, military leaders should not provoke war out of wrath.”10 Personal combat should be viewed no less critical and be approached in the same way. When emotions flare, fights erupt. Thus, the better option is to avoid battle if possible, not out of compassion for the enemy, but to preserve life.

Popular martial arts further suggest that the reason why we learn to fight is so that we do not have to fight. To ease the way to victory, Sun Tzu warned us not to press an enemy that is cornered, but to “leave an outlet,” a gate to life.11 Humiliation can prompt an adversary to fight to the death even in a hopeless situation. As military historian Victor Davis Hanson writes about the World War II battles on Okinawa:

Americans were convinced that Asians in general did not value life—theirs or anyone else’s—in the same manner as Westerners, and when faced with overwhelming military power and sure defeat would nevertheless continue to fight hard... The Japanese quit on Okinawa when they were killed off, not when the fall of a particular ridge or line of defenses forecast eventual tactical defeat... War ended when the enemy was exterminated or faced with certain annihilation. It did not necessarily stop when the Japanese were encircled, outmaneuvered, or shorn of supplies.12

Sun Tzu further advocated weighing the risks carefully before entering battle and considering the benefits that victory will bring, as demonstrated through his statement, “[I]f there is no gain, do not use troops.”13 This is a reminder to the martial artist that his is an activity that deals in the reality of combat and therefore in life and death, and that he must use his power judiciously. Furthermore, when the victor is gracious, better future relations can be ensured between the parties. Guanxi, emphasized in Confucian doctrine, is a relationship of trust and general awareness of the needs between two people, and through which balance and harmony is achieved and hostilities are calmed. However, it might be worth noting that harmony can generally not endure “without a sense of obeisance from the weaker partner.”14 From a practical viewpoint, the idea of leaving the enemy an out and not humiliating him in defeat is important only because it is aimed at creating a lasting victory by discouraging him from returning with a vengeance. It does not mean that one should avoid using full force when one’s life is threatened. Do not assume that an enemy who is neutralized momentarily will leave you alone if given the chance to replenish his forces and rise again.

Sometimes victory can lead to intoxication with success and over-confidence in future battles, and may prevent one from conducting a proper examination of the enemy and oneself. The martial arts typically teach adherence to a policy of humility. A martial artist who avoids bragging about his accomplishments and lets his skill speak for itself decreases the risk of underestimating the opponent’s skill or overestimating his own. Since he can never fully prepare for the effects of friction, physical and mental preparation must be a continuous effort based on realistic expectations. When examining war critically, examining the means employed and not just the end result seems like a valid suggestion. However, in the pursuit of victory, a particular means “is not fairly open to censure,” according to Clausewitz, “until a better is pointed out.”15 Victory is achieved only when the enemy accepts defeat. Thus, ultimately, only the end result matters.

Furthermore, stability in conflict is seldom achieved in full and in agreement with the victor’s terms, which illustrates the meaning of Clausewitz’s statement that “in war the result is never final” but merely a transitory evil for the defeated power.16 If you win a kick-boxing match today but are challenged to a rematch tomorrow, the outcome may not be in your favor. You may protect yourself against theft today, but be taken by surprise tomorrow. Thus, a “military victory” today does not guarantee a lasting victory tomorrow. You might also experience a so-called Pyrrhic victory (relating to the staggering losses that King Pyrrhus of Epirus, a Greek general of the Hellenistic era, took when defeating the Romans in 280 and 279 BCE) by winning in theory, yet walking away with losses so heavy that you wonder if the battle was worth fighting at all. This is yet a reason why one should not take war lightly or enter battle carelessly.

Although defense is the stronger form of war, both Sun Tzu and Clausewitz understood that victory lies in the attack. As discussed in chapter 7, the purpose of defense is to await an opportunity to attack an enemy who has been weakened by time. But perpetual defense cannot win the war. You must take action at some point. Battle, according to Clausewitz, “is a conflict waged with all our forces for the attainment of a decisive victory.”17 This statement demonstrates his concern with the effectiveness of battle and not with its ethics or morality. He did not view physical conflict in terms of “a search for truth or justice but only as a struggle of wills.”18 The best fighter is not he who adheres to the greatest morals, but he who wins.19

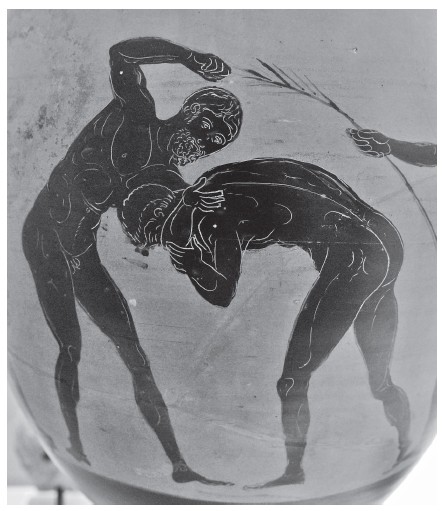

Sun Tzu took no less of a pragmatic approach to battle. He believed that “one who knows how to use both large and small forces will be victorious,”20 for example, by combining the crude pounding of the opponent into submission (use of large forces) with the finesse of a joint control hold (small forces). Although many factors contribute to the success or failure the martial artist experiences on the street or in the ring, the use of certain techniques, such as the reverse punch or the figure-four choke depending on one’s style preference, might help some martial artists win fights. An unswerving determination also plays a crucial role. According to karate legend Mike Stone, “There are a lot of fighters I’ve fought who are physically stronger than I am. But I think that I have a greater desire that makes up for the difference... if I lack either speed, power, or ability, I try to make up for it in desire, and, you know... I don’t want to lose... I have to win!”21

Proficiency in the techniques favored by your martial art, and the use of “large” and “small” forces, can increase your chances of scoring a victory, as demonstrated in this ancient artwork of a pankrationist applying a choke simultaneous to pounding his opponent into submission. (Image source: Marie-Lan Nguyen, Wikimedia Commons)

Because of the difficulties inherent in finding an ethical solution to conflict, it is not immediately apparent whether the “better” martial artist is he who relies on force to destroy the enemy’s fighting capacity, or he who uses diplomacy and manages to resolve the conflict without fighting. A comment about which martial art is “better” is in place: Those who claim that traditional martial arts are not suited for the streets of modern society may be correct in the sense that a fighting art was developed to suit the terrain and counter the tactics of the particular enemy of the times. But it should also be borne in mind that the traditional martial arts were developed for the purpose of killing and not for sport or health benefits. As has been demonstrated repeatedly throughout this book, they were brutal systems of fighting that frequently resulted in the death of the losing party. Moreover, rules and safety measures imposed in competition tend to prevent modern martial artists from displaying an accurate image of an art’s effectiveness.

Because of the dual nature of war where both belligerents have access to many of the same tactics, violence can generally not be avoided in one’s pursuit of victory. The erroneous interpretation of Sun Tzu’s emphasis on winning without bloodshed leads to the “implication that war can somehow be turned into a non-lethal intellectual exercise in which cunning and intelligence are central. On the other hand, the erroneous interpretation of Clause-witz’s emphasis on force and the principle of destruction can cause force to be wielded too readily, without the careful consideration of non-military means; this would only make war more costly than necessary.”22 Despite these fallacies, when battle is inevitable both strategists considered victory the object of war. Clausewitz stated that “[v]ictory alone is not everything—but is it not, after all, what really counts?”23

The idea that what matters is “how one plays the game” is not advocated by either strategist and is also one of the great falsehoods of sports history. You might enjoy yourself thoroughly at a martial arts competition even if you lose, but ultimately it is winning that builds your reputation. If you do not win or win often enough, you will not progress in competition sports. An athlete who fails to win will find few opportunities to compete against more skilled opponents, and he will definitely not go to the Olympics. If competition is your game, winning is pretty much everything. If survival is your game, winning is certainly everything. When engaging an enemy, whether in actual combat or in a sanctioned bout with judges and safety personnel on standby, you must engage him with full intent on winning. If winning does not matter to you, considering the inherent dangers of combat, it is better not to fight at all.

As has been explored repeatedly, both strategists also considered a quick victory of the essence. As echoed by the ancient Greek historian Thucydides: “Consider before you enter how unexpected the chances of war be. For a long war for the most part endeth in calamity... And men, when they go to war, use many times to fall first to action... and when they have taken harm, then they fall to reasoning.”24 Although Sun Tzu and Clausewitz agreed that “a victory that is long in the coming will blunt [your] weapons and dampen [your] ardor,” and a prolonged campaign will likely deplete your resources,25 the idea that “[n]o nation has ever benefited from protracted warfare”26 must be placed in perspective. As demonstrated in chapter 7, fighting a protracted battle from the defensive position is sometimes the wiser strategy for winning the war. However, the end goal is not to prolong battle, but to wait for a moment that will give one a relative strength advantage. Whether or not you are the instigator of battle, you can enjoy a quick victory only when your forces are superior.

Sometimes, a nation or an individual has no choice but to go to war (as may be the case if the alternative is death, rape, or injury, and even submission or humiliation), yet lacks the capacity to fight for decisive victory. A person who is kidnapped might want to rely on a protracted strategy and extend the “war” as long as possible rather than risk injury and death, in the hope that he will receive assistance from the outside. In an officially sanctioned martial arts bout, a fighter might get injured or exhaust himself prematurely and be forced to revert to fighting a protracted battle. The more difficult it is to achieve the objective, the greater the risk of long periods of inaction. Ultimately, the act of war should be a rational undertaking and lead to the achievement of some gain or higher political objective. If, as the conflict progresses, it becomes evident that you have no chance of scoring a victory, it is better to admit defeat or attempt to engage in diplomatic negotiations to save life rather than pursuing the fight. Continuing to fight simply to save face and escape humiliation at this point would be irrational.

Furthermore, numerical superiority is only one factor that increases one’s relative strength advantage. A slight superiority may not guarantee victory. Sun Tzu recommended at least a two to one superiority ratio for attacking and dividing the enemy, and, if equally matched, to engage him only with some good plan.27 Secondly, in order to benefit the most from numerical superiority, the troops must be brought to action at the decisive point. There are battles where the inferior force has won against greater odds, but they constitute the exception rather than the rule. Since numbers are so important, one should strive to enter the field of battle with an army as strong as possible. If the greatest number of troops one can muster proves insufficient, one must decide whether it is possible to beat the opposing force through other means such as superiority in tactics or weapons.

When physically inferior, a weapon can give you a strength advantage, split the opposing force, and allow you to secure the victory. (Image source: Edith Levinet, Wiki-media Commons)

Although the aim for a quick and decisive victory is paramount in both Sun Tzu’s and Clausewitz’s opinions of combat, the nature of the aim; whether offensive (to destroy the enemy forces) or defensive (to prevent destruction), determines how one approaches battle. Combat does not happen in isolation from the surrounding circumstances. Whether combat involves a threat to your life or an agreement to accept a martial arts bout in front of a large audience, the situation tends to build over time and involves the acceptance of risk. Generally, threats away from the training hall have their roots in some kind of strategy that can be detected by an observant person before the situation has developed to the point of no return. A parallel can be drawn between Sun Tzu’s focus on deception and Clausewitz’s statement that “all war supposes human weakness and against that it is directed.”28 For example, a person planning to attack another is likely to lie in ambush or seek a victim that he believes is unable to counter the attack.

The ease or difficulty with which you secure the victory also has to do with the importance of the objective. If the objective is of small value (your wallet, for example), you will be less concerned with pursuing it than if it is of great value (your life or safety). Physical and mental capacities to undertake the fight determine which political objectives a person will fight for and which he will abandon. For example, a person who has rape as his goal, when discovering that his victim is no easy take, may be satisfied with merely stealing her purse. In other words, the political objective can change when he discovers that he does not have the capacity to pursue the fight in the desired manner.

Sun Tzu’s Art of War is said to hold the key to victory, but can it prophesize how future battles should be fought? If one understands Sun Tzu’s lessons, will one necessarily prevail? A war must be winnable in order to be considered a war. Otherwise we would be in a perpetual state of war and would not understand the definition of peace, in which case there could be no definition of war. Although Sun Tzu is said to have had one of the greatest military minds in history because he presented his ideas as a “cohesive, holistic philosophy of how to approach strategy,”29 when saying that he predicted the outcome of modern wars, we are really relying on hindsight which is always clear. The idea that the Art of War can predict how a battle will unfold, or whether or not it is actually winnable, holds little value for future warriors or martial artists.30

How do you know, then, when you have achieved victory? Victory can be conceived when the enemy’s loss is great in physical or moral power, or when he relinquishes his intentions. One wins wars not by conquering enemy territory, but by targeting the heart of the enemy’s power. Although it has been tried many times, victory is not earned through a simple declaration. As Thucydides, the great historian of the Peloponnesian War, warned us in the fifth century BCE, first the Corinthians set up a trophy. Then the Corcyraeans, “as if they had the victory, set up a trophy likewise.”31 The Corinthians believed they were the victors, because they had caused more destruction and killed more of the enemy. The Corcyraeans, by contrast, believed they were the victors, because they had sunk thirty galleys of the Corinthians and recovered heaps of dead bodies, and because the Corinthians the previous day had rowed away from them in what was perceived as an act of cowardice.

This example illustrates why victory must be defined in order to have meaning. For example, does victory mean conquest or simply defense? Does victory mean total annihilation with significant and lasting control over a country or person’s territories and political systems? Or does it merely mean winning a single battle even if you are defeated at some later date? If victory must have lasting impact, how is “lasting” defined? Winning or losing to Sun Tzu was as much a psychological as a physical state. In other words, if the defeated enemy does not acknowledge defeat, he has not lost the battle no matter how brutal the physical beating. The vanquisher must instill a mental acceptance of defeat in the vanquished. A parallel can be drawn to Daoism where the principal object is the restoration of harmony for healthy living. When one unsettles an opponent, harmony is destroyed, which leads to loss of morale. It is therefore possible to win psychologically even if the enemy forces are still intact.

As has been demonstrated repeatedly through the examples provided in this book, it is exceedingly difficult to calculate victory, or to find a formula for success that works every time. Battles are fought against a variety of opponents and under different circumstances (not all battles are fought in a 20 by 20 foot ring, for example). Not only may you have witnessed martial arts matches where you thought that one fighter was unfairly “robbed” of the decision, a martial artist who loses a match today does not have his fate determined for time and eternity, but can adjust his training methods and tactics, make a comeback tomorrow, and emerge victorious. The reverse is also true. Royce Gracie astonished the world by dominating the Ultimate Fighting Championship from 1993 to 1995. Now other fighters have moved in and taken his place in the spotlight and demonstrated that matches are won, not merely through skillfully applied chokes and arm bars, but also through the crude pounding of the opponent into submission. The focus has shifted to a methodical approach of massed attack where physical strength, endurance, and the sheer volume of blows trump cunning and finesse. This example reinforces the idea that history is seldom an accurate indicator of success or failure in future conflicts.32

Furthermore, whether or not your decision to fight is wise can often be evaluated only after the fight is over. If you emerged victorious, you will say that your decision was wise. If you took a beating, you will say that it was not. The fact that we have to rely on hindsight in order to determine whether or not a particular choice was sound is one reason why it is difficult to use books, including this one, to predict success or prescribe certain procedures for combat. History does not repeat itself. Yes, we can always look back and comment that a particular person was able to use Sun Tzu’s principles successfully and score a victory. But we cannot look forward with the same confidence and say that we will be victorious if only we rely on the principles prescribed in his book. Since the application of a theory of war to specific situations requires creativity and intuition, the writings of Sun Tzu should be used as pillars of strength and not as predictions for victory.

To Clausewitz, whether or not an individual is victorious is a matter of mentality, morale, physical capacity, intellect, and practical experience rather than theoretical reasoning or prescribed patterns of training. One must prepare to use one’s power to its fullest and always in proportion to the enemy’s resistance. If his resistance is great, then great exertion is needed to overcome him. If certain “military virtues” such as physical strength are lacking, the combatants must compensate for them in other ways, for example, by relying on the defensive position until the odds can swing in one’s favor.

In the end, victory is dependent on achieving the political objective. When the political objective is achieved, the aggressor will stop fighting. A robber who asks for your wallet will take it and run if you give it to him, because he has reached his political objective without an exchange in blows. Although the altercation may be resolved without bloodshed, it is the threat of combat that prompts one to succumb to the enemy’s will. Before engaging an aggressor, one must ensure that the objective is of greater value than the sacrifice. The aggressor must likewise make a similar determination. If the person confronting you has a weapon, you might decide that his political object(ive), your wallet, is not worth risking your life over, so you hand it to him. But if he threatens to kidnap you, you might decide to fight because his political objective, possibly rape or murder, warrants total defensive action even at the cost of injury or death.

Everything that we have studied so far—the nature and conduct of combat, the definition of war, physical and mental preparation, elements of tactics and strategy, imposing your will on the enemy, the destruction of the enemy force, the strength of the defensive position, the consequences of failure, and the value of courage and responsible action when under threat—are steppingstones toward the achievement of a lasting victory. The best way to preserve peace after victory is achieved may be by maintaining a modest attitude rather than bragging about one’s feats. As reinforced by the Ssu-ma Fu, one of the classical Chinese military texts, “After a victory one should act as if victory had not been achieved.”33 Lasting peace can come through the total annihilation of the enemy, but it can also come through diplomacy that leads to a mutual agreement to end the conflict. How effective one is as a fighter may therefore be determined by the end and not the means; by what one achieves rather than how it is done.

Soldiers with the People’s Liberation Army at Shenyang training base in China. Sometimes a display of force can prove sufficient for averting a war. (Image source:

D. Myles Cullen, Wikimedia Commons)

The best advice that Sun Tzu and Clausewitz had for us may be that victory is prepared in the planning, and that one should not take “the first step without considering the last.”34 Or as Sun Tzu stated, “a victorious army tries to create conditions for victory before seeking battle.”35 When the goal and the steps have been identified, the manpower and weapons have been brought together, the training has been conducted, and the logistics are in place, you can fight with good spirit and be fairly confident in your ability to emerge victorious.