When Ramesses I died, ending his short reign, Seti – as prince regent and heir apparent – immediately ascended to the Horus Throne of the Living. His official coronation, however, could not be conducted until the embalming and burial rites of his predecessor were concluded. There are no sources which tell us specifically what tasks Seti faced during this potentially unstable interim period between ascension and coronation. He must have spent a great deal of his time solidifying his power base within the court and guarding against any whispers of usurpation or stirring of rebellion.

Among the most pressing concerns, however, was the choosing of his five royal names;¹ the names which – like all Egyptian pharaohs before him – were used both to express policy and to attempt to pre-emptively encapsulate the essence of a ruler’s personal ambitions for his reign. The process of choosing the five names is somewhat obscure, although the Coronation Inscription of Hatsheptsut² from the mid-18th Dynasty does suggest that the actual formulation of the complex names was conducted by groups of lector-priests, no doubt under the watchful eye of the king. After the coronation, the five names were engraved on new and repurposed monuments throughout the land. A decree sent by Thutmosis I to Turi, his viceroy in Nubia, shows this promulgation of the royal names in action:

‘ My Majesty, life, prosperity, health, has appeared as the Dual King upon the Horus Throne of the Living, there has never been anyone like him. My titular is the following:

“ The Horus: Victorious bull, beloved of Maat – The Two Ladies: The one who has appeared by means of the Uraeus, the one great-of-might – The Golden Horus: The one perfect of years, who Houses of Life and Eternity 79 has sustained minds – The King of Upper and Lower Egypt: The Great one is the manifestation of the ka of Re – Son of Re: Thutmosis, living forever and ever.”’³

No doubt similar decrees were despatched to pharaoh’s representative in the provinces within Egypt itself, and to those – like Viceroy Turi – who served the king in foreign lands.

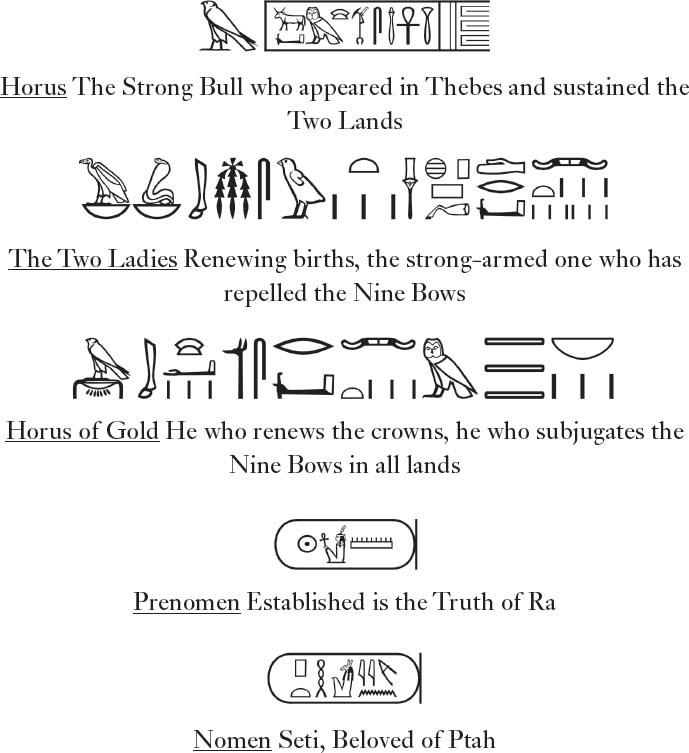

Seti’s five names are intensely political and they provide us with a rare glimpse into the mind of the young prince regent as he stood on the threshold of power. What were his ambitions and what type of ruler did he seek to become? The first hint is found in his second name, The Two Ladies. Within this lengthy titulary is the phrase Wehem Mesut, which literally translates as ‘Repeater of Births’. This phrase had been used since the Middle Kingdom to denote a planned renaissance; a return to normality or prosperity after a perceived period of unrest or social upheaval. It was first used by Amenemhat I, the first pharaoh of the 12th Dynasty, to symbolize a definitive break with the decentralization of the First Intermediate Period and the return of unchallenged consolidated monarchical rule. A similar title was incorporated into the names of Tutankhamun, Horemheb and Seti’s own father, Ramesses I, but unlike these three kings – cursed by short reigns and/or lack of progeny – Seti was the first ruler who delivered on the promise inherent in the name. His reign marked a definitive break with nearly every aspect of the Amarna and Post-Amarna Period, as well as forming the basis and consolidation of the Ramesside Period of the later 19th and 20th Dynasties.

The five names of Seti I

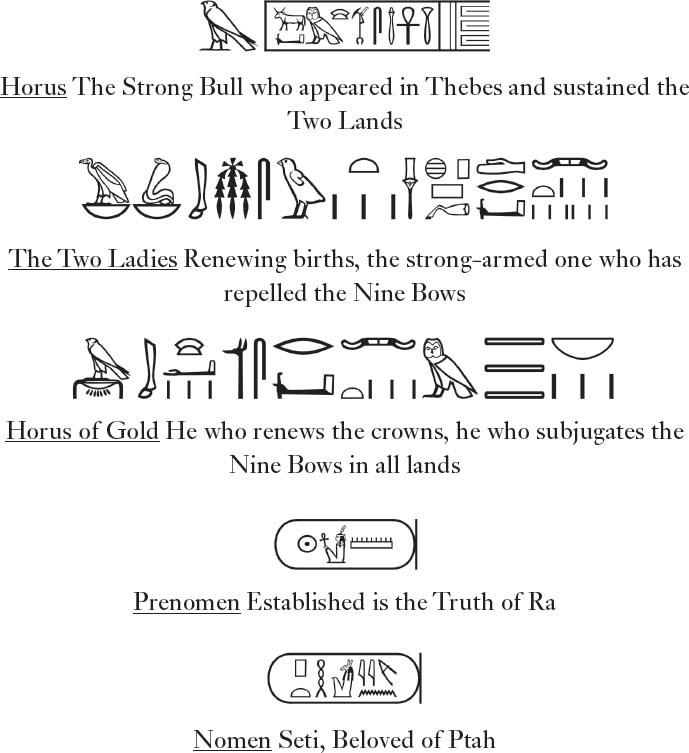

The prenomens of Seti I, Thutmosis III and Amenhotep III

In terms of inspiration and aims, Seti’s prenomen provides an intriguing clue. Along with the king’s personal name (his ‘nomen’), the prenomen was far more widely used – and probably well-known within the population – than the entire titular. It was both engraved on monuments and used to decorate small everyday objects, such as vessels and jewellery. Seti chose as his prenomen the phrase ‘Established is the Truth of Ra’, which is pronounced in Egyptian as ‘Men-maat-ra’. This phrase is a merger of two 18th Dynasty prenomens belonging respectively to Thutmosis III (Men-kheper-ra, ‘Established is the Manifestation of Ra’) and Amenhotep III (Neb-maat-ra, ‘Lord of Truth is Ra’), taking the first part of the prenomen of Thutmosis III and joining it to the second part of that of Amenhotep III. The symbolism and intended message conveyed by this piece of amalgam is clear: Seti saw himself as the heir to the two greatest kings of the 18th Dynasty; Thutmosis, the Warrior, and Amenhotep, the Builder. Seti’s exploits in the Levant, Libya and Nubia certainly earned him a place among the great warrior kings like Thutmosis. But it was his apparent determination to outshine Amenhotep as a builder, endower and expander of temples throughout Egypt which more than anything defined much of his reign.

‘Let it be made just like that of ancient times’: Art and Artistry in the Time of Seti I

The innovative and aestheticizing art form championed by Akhenaten and described as ‘Amarna’ or ‘Atenist’ art in scholarly literature, rapidly began to fade after Akhenaten’s reign, although some of its basic characteristics remained during the post-Amarna Period in the form of a more naturalistic expression of the royal form. Certain depictions of Ramesses I even retained these characteristics, such as a wooden figure of the king, which may originally have come from his tomb and is now housed in the British Museum.⁴ In appearance it is difficult to distinguish from similar works of art attributed to the reign of Tutankhamun, and it suggests that even though the political influence of the Aten cult was well and truly ended by the advent of the 19th Dynasty, the art form it originally inspired still held some sway.

When Seti ascended the throne, the first item on his domestic agenda was to ensure that the damage he felt had been caused by the Amarna pharaohs was expunged from history. He conducted a campaign of restoration of temples and chapels which had either been vandalized or simply left to deteriorate during Akhenaten’s reign, including the temple of Ptah at Memphis,⁵ which he endowed with new limestone reliefs. These depictions, executed during the very earliest period of Seti’s reign, are still firmly in the post-Amarna style of his father, but by the fourth year of his reign an evolution towards a more distinctive Ramesside style of relief carving is evident. Some scholars have – perhaps unfairly – compared this carving style unfavourably to the more virile and graceful reliefs depicting everyday life and historical scenes carved during the mid- to late 18th Dynasty, complaining that Seti’s reliefs were too conservative and too static in their composition and expression.⁶ It is clear from contemporary textual sources, and also from the reliefs themselves, that the art form Seti favoured was indeed in some ways conventional and represented a quest for a return to ‘normality’ after the experimentation of the Amarna Period. But any notion that there was no evolution, no innovation expressed during Seti’s reign is a fallacy. Rather, the art of Seti I represented an interim period between the naturalism and innovation of the Atenism and Post-Amarna art forms and the dogmatism of the later 19th Dynasty. It was a period where experimentation met conservativism – expressed in a tendency towards archaism – but where no force held complete sway over the other, merging to produce some of the finest pieces of relief and sculpture of the New Kingdom.

Sculptural pieces in the round which depict Seti are comparatively rare, a dearth which has prompted scholars to focus their attentions on the copious reliefs carved during his reign. There are, however, two pieces of royal sculpture in particular which ably demonstrate the interplay between orthodoxy and innovation, along with the unusually high standard of craftsmanship which typified Seti’s reign, and contrast so clearly with the sloppier work created during the reign of his son, Ramesses II, and his descendants.

Cairo CG 751⁷ was found by the French Egyptologist Mariette at the Middle Egyptian site of Abydos and is currently held in the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. The statue is carved from dark grey schist and shows the standing king holding a standard (now broken) in his left hand. After Seti’s reign, this particular type of royal statue gained in popularity and many later Ramesside rulers chose to be depicted in a similar manner, as did members of the elite.⁸ The innovative aspect of this particular depiction of Seti is his wig, composed of long lappets of wavy hair gathered into braids or tresses. This particular type of headgear was commonly associated with private members of the military elite during the 18th Dynasty,⁹ and was not as a general rule used in depictions of royalty. Seti, however, appears to have retained a fondness for this type of wig, which he and his father had undoubtedly worn before their ascent to royalty after the reign of Horemheb. The reasons behind this preference are unclear, but it is tempting to speculate that this military-style wig represented a subtle nod by Seti towards his and his family’s military past. The regnal year when the statue was carved has not been preserved, but the more mature Ramesside features – a slightly hooked nose, elliptical face and full cheeks – are generally considered hallmarks of the latter half of Seti’s reign.

A granite statue of a kneeling Seti from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York,¹⁰ by contrast, has distinctly archaistic characteristics. The king is depicted wearing the nemes headdress, and has a false beard strapped to his chin, his arms extended, supporting a laden offering table. The posture, garments and facial features of the statue bear undeniable similarities to 18th Dynasty royal statuary.¹¹ This desire for a return to traditional forms of statuary during Seti’s reign is also clearly expressed in the Biography of Paser, who served as Seti’s vizier in Thebes. The biography describes how Paser visited a sculptor’s workshop, presumably at the Karnak Temple, and gave instructions to the artists:

‘ May Ptah favour you, O sculptor! Extremely good is this statue of the Lord which you have made. “Let it be made just like that of ancient times” - so it was said in the Palace.’¹²

In other words, Paser directly conveyed an order that was sent out from the Palace and from Seti himself; that the artists should take inspiration from the statues produced before the Amarna Period, and emulate the older style. This tendency towards archaism, coupled with an enduring proclivity for gentle innovation on the part of the artists, helped to define the mature Ramesside art form for several centuries.

* * *

The inhabitants of the Nile Valley during Seti’s reign saw their world as one of duality. They were citizens of ‘The Two Lands’, one comprising the Nile Valley and the other the Nile Delta. But they also juxtaposed the fertility and abundance of the silt-laden river valley, which they called ‘The Black Land’ (Kemet), with the arid deserts that flanked their world, known as ‘The Red Land’ (Ta Djeseret). The desert provoked a fear of the unknown; it was a place of death, rather than of life, and was not ventured into lightly. But along with unknown terror, the desert wastes also held resources crucial to the elite – the king and the temples. Along the edges of the desert were outcroppings of limestone, sandstone, alabaster, granite and the manifold other types of stone, hard or soft, used to create architectural elements for temples, statues of gods and kings, and also private funerary objects, like stela and offering tables. Further afield, in the eastern desert and on the Sinai Peninsula, were precious minerals like gold, copper and turquoise, used both for trade and as diplomatic gifts, but also to manufacture tools and weapons or to adorn the images of gods. The variety of valuable minerals used in the decoration of divine images is described in the 12th Dynasty Stela of Ikhernofret from Abydos:

‘ I adorned for him [the god Osiris] his great barque for all eternity. I made for him a palanquin bearing the beauty of the foremost of the westerners, of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, bronze, Sesenedjem-wood and cedar of Lebanon […] I bedecked the chest of the lord of Abydos with lapis lazuli and turquoise, electrum and every costly stone as decoration for the limbs of the god.’¹³

But the desert did not surrender its treasures easily. To maximize the quarrying and mining operations, it was generally the central authority in Memphis, namely the king or alternatively local nomarchs and governors who despatched expeditionary forces comprising scribes, overseers, masons, carriers and military personnel to bring back the desert’s bounty. In some cases, when the required minerals were located deep in potentially hostile territory, attendant infrastructure was constructed to protect the expeditions. Seti’s clear aim, apparent even in the early part of his reign, was not just to re-establish or repair existing temples and chapels. Rather, his throne name shows his desire to step into the shoes of Amenhotep III, one of the major builders of the New Kingdom. But such a grand ambition required a steady supply of raw materials.

* * *

The construction of a temple required both a softer stone, like limestone or sandstone, for the architectural elements – such as walls, columns, porticos and some statuary – and harder stone, like quartzite and – most importantly – the black Aswan granite used for obelisks and statues. Already in the second year of his reign, presumably following the swift Year 1 campaign against the Shasu in Sinai and city states in the Levant, Seti turned his attention to the sandstone quarries at Gebel Silsila, located in southern Egypt, 60km north of the First Cataract at Aswan.¹⁴ A massif of fine-grained and relatively durable sandstone lay exposed there, along the Nile, and this proximity of the raw material to the main transport artery in Egypt – along with the quality of the stone itself – had drawn the attention of the central state since the Old Kingdom, although major quarrying operations are not attested archaeologically until the Middle Kingdom. With the gradual shift from limestone to sandstone as the predominant building material for temples and other official structures during the New Kingdom, these quarries became more prominent.

Evidence of use by 18th Dynasty rulers such as Hatshepsut, Thutmosis III, Amenhotep III and Akhenaten now litter this ancient quarryscape, predominantly in the form of inscriptions, either official stela recording royal missions or more informal graffiti left behind by the quarrymen themselves. A plethora of rock-cut shrines, mostly dedicated to the local deity, the crocodile god Sobek, were also installed by the New Kingdom pharaohs who sent expeditions onto Sobek’s territory and naturally wished to appease such a ferocious god. The most notable structure on the West Bank of the quarries is the Speos of Horemheb,¹⁵ a much grander rock-cut chapel carved into a hillside. The high-quality decoration of the Speos was not finished during Horemheb’s lifetime and the structure became a curious amalgam of royal attention, with various Ramesside rulers, including Seti himself, adding their cartouches to the unfinished decorative scheme. Ramesses II even went so far as to add an entire relief to Horemheb’s chapel which celebrated four anniversaries of his reign; his thirtieth, thirty-fourth, thirty-seventh and fortieth year in charge of the Two Lands.

Seti’s expeditionary force landed on the West Bank, close to the quarries already opened by earlier New Kingdom rulers and immediately south of a series of Ramesside funerary chapels. There, the artists who accompanied the workforce carved two large stela into the side of the sandstone massif.¹⁶ Both are wholly rhetorical and contain little pertinent information about the composition of the workforce or their day-to-day activities. Where textual sources fail, archaeology can present an alternative source of facts, and it is possible to reconstruct the method of extraction from material remains. The relatively soft sandstone which lay openly exposed could be quarried with heavy bronze chisels, the blocks loaded onto wooden sledges and pulled on rollers the short distance to the river bank. Along the bank are remains of both high- and low-water loading ramps that allowed the blocks to be manhandled down to the required level and shifted onto large wooden barges. From there, they could be shipped easily throughout Egypt. A harbour basin was also cut into the bedrock,¹⁷ measuring over 100m in length, and with a short canal it permitted passage of a ship from the river. Anchoring holes were carved into the sides of the basin, so that the transport barges could be securely held in place and the quarried blocks moved on board via one of several long transport ramps.

Seti’s aim in sending a quarrying expedition to Gebel Silsila so early in his reign is clear. Among his first priorities after taking power was the construction of the Karnak Hypostyle Hall and – crucially – the sandstone walls surrounding it. It was upon these walls that artists would carve the extensive war relief commemorating Seti’s campaigns abroad. The majority of the blocks quarried during this expedition at Gebel el-Silsila were therefore most likely shipped the 180km north to the sprawling construction sites ringing the Karnak Temple.

By Year 6 of his reign, following his initial spat with the Hittite Empire and in the same year that he took action against the Libyan nomads in Tjemeh-Land, Seti sent another workforce south to Gebel el-Silsila. This time the expedition worked in the quarries on the East Bank, and again, a dedicatory stela commemorating Seti and his works was carved into the sandstone by the side of the quarry road. This text is more illuminating than the wholly rhetorical texts written four years before on the opposite bank, and even includes a comprehensive list of foodstuffs given to the members of the quarrying expedition by the benevolent king:

‘ On this day His Majesty Life-Prosperity-Health, was in Thebes doing what pleased him and his father Amen-Re, King of the Gods, spending the night awake, seeking blessings for all the gods of the land. When dawn came and the next day appeared, His Majesty Life-Prosperity-Health, commanded that an envoy of the king Life-Prosperity-Health together with a troop of 1,000 soldiers be gathered […] to ferry monuments for his father Amun-Re and Osiris together with his retinue of gods […] Every man among them received 20 deben of bread every day, bundles of vegetables, roasted meat and two sacks of grain every month.’¹⁸

Housing and feeding such an extensive cohort no doubt presented an intense administrative task and required extensive infrastructure. The primary archaeological evidence of this kind of infrastructure takes the form of workmen’s huts; simple round or oval shelters built from drystone and thatched with reeds.¹⁹ Vast conglomerations of pottery near these structures dating from multiple periods may indicate rubbish heaps. But there has, as yet, been little targeted investigation of the subsistence strategies and production methods that were used to feed the hungry quarrymen, scribes, soldiers and various officials. Twenty deben of bread, roughly 1.8kg in modern metric terminology, is a substantial amount, providing more than 5,000 calories; nearly twice what was given to other corvee labourers on state projects.²⁰ It is not clear why the workers at Gebel Silsila were so comparatively well-fed, although as is common with royal monumental inscriptions from Egypt, it is possible that the text simply exaggerates the actual types and variety of foods given to the workers.

A private inscription from the Year 6 mission to Gebel Silsila²¹ provides us with a testimony from one of the leaders of the work gang: Hapy, the Superintendent of the Expedition and also the Chief of Retainers. On a small rock stela dedicated to the Lord of Silsila (possibly Sobek), Hapy proudly describes how he himself was praised by his king and entrusted with the responsibility of supervising this crucial mission which would bring building material to the many construction sites throughout Egypt. The destination of the sandstone from the Year 6 expedition is unclear; sandstone was widely used in multiple temples during Seti’s reign. It is, however, tempting to guess that the lion’s share was intended for Seti’s own mortuary temple on the Theban West Bank which was beginning to rise out of the surrounding desert sand to stand as an eternal testament to the king’s soul and his glorious reign.

With these two expeditions to Gebel Silsila, Seti had ensured a steady supply of the basic building material which, together with limestone of varying quality from several different quarries, would be used to raise and repair temples in his name. As the years passed and many of these temple projects neared completion, however, the time came to begin filling these holy structures with colossal images of the king and great obelisks carved from imperishable granite.

* * *

Year 9 found Seti in the south, this time to commemorate the opening of operations in the granite quarries on the West Bank of the Nile near modern-day Aswan. In a small stela inscribed directly into the granitic bedrock during his reign, Seti claims to have: ‘Found a new quarry for great statues of black granite.’²² This claim is somewhat unlikely. In fact, Seti was merely returning to the Aswan quarries after an apparent eighty-year hiatus since the reign of Amenhotep III, the very king whom Seti wished to emulate.²³ Going back to the Old Kingdom, state-sponsored expeditions were sent to quarry the granodiorite and rose granite which rises from the surrounding Nubian sandstone around Aswan and on the islands of Sehel, Saluga and Elephantine, and some of the most notable pieces of sculpture from ancient Egypt – including the Memnon Colossi and Rosetta Stone – are carved from this hard rock.

Unlike the softer sandstone or limestone, granite could not be extracted using metal chisels. Instead, heavy granite and dolerite pounders of varying shapes were used to strip the weathered crust off suitable boulders and painstakingly carve out the rough shape of the desired object. Secondary processes like dressing the surface would most likely also be conducted at the quarry before the final carving and polishing was undertaken at temple workshops throughout Egypt. For larger objects such as colossal statues, obelisks and shrines the quarrymen could choose to enlarge existing fractures in the bedrock in a process known as ‘wedging’, or alternatively use rapid heating and cooling of the rock surface with fire to induce fracturing. In Roman times, a process of driving wedges into natural or man-made fractures, thereby splitting away large chunks of rock, was also used extensively at Aswan.

The process used for the quarrying of granite for obelisks was more simplistic. When a suitable area of granite bedrock was identified, the ground was roughly flattened using simple stone hammers, and the rough outline of the obelisk traced. Channels were then carved in the rock around the shape of the obelisk before it was separated from the bedrock entirely by carving under its bulk. Once the obelisk was removed, it was even possible to continue the channels further down and quarry a second obelisk from the new face of the granite bedrock exposed by the removal of the first.

Seti’s ambitions at Aswan are remarkably clearly spelt out in the two stelae which were carved into the rock face at the quarry in commemoration of the monarch’s visit:

‘ His Majesty Life-Prosperity-Health decreed a multitude of works: to make great obelisks and statues great and wonderous upon the name of His Majesty Life-Prosperity-Health. He built great barges for ferrying them with crews within them, ferrying them from the quarry with courtiers and workmen […] And his first-born son was before them, doing service beneficial to his Majesty.’²⁴

This inscription goes beyond the customary laudations of royal might one expects of Egyptian monumental inscriptions, and alludes to the complex infrastructure required to transport the immense pieces of granite. Archaeological evidence from around the West Bank quarries used by Seti’s quarrymen adds to the textual descriptions and shows that the expedition constructed slipways, ramps and a 2m-wide paved road leading to the river. The granite monuments could in this way be dragged on wooden sledges, most likely set atop rollers, from the quarry to the river-bank. There, they would be loaded onto unwieldly barges and (painstakingly slowly, one might imagine) be transported to their varied destinations throughout Egypt’s major temples and cities. A unique relief and accompanying inscription in the mortuary temple of Seti’s predecessor, Hatshepsut, at Deir el-Bahri²⁵ shows two of the great granite obelisks Hatshepsut raised at Karnak being transported down the Nile in this fashion. The two obelisks – each 30.7m long – are depicted lying base to base on a 63m-long barge, which is in turn is being towed by dozens of smaller craft. A linesman stands near the prow of the leading tow vessel, using a pole to gauge the depth of the river and alert the flotilla to the presence of sandbanks or other obstacles. Even aided by the current going downstream, it must have represented both an exceedingly complex – and also dangerous – operation, and an astounding feat of engineering. The great barges described by Seti in his inscription were no doubt intended to function in a similar manner.

The most pressing question in relation to Seti’s operations at the granite quarries in Aswan is: where are the ‘multitude of works’ the king decreed? At Aswan itself, only the tip of a small 12m obelisk remains, most likely abandoned due to a flaw in the stone which became apparent during the carving of the decoration. Aside from this paltry piece of sculpture, and a handful of smaller statues of the king carved from black granite, the only truly grandiose granite monument which can with certainty be ascribed to Seti is the so-called Flaminian Obelisk.

Quarried at Aswan and decorated on three sides during the reign of Seti I, this 23m-tall obelisk was intended for the temple of the sun god Re-Horakhty at Heliopolis. It is likely that Seti himself had died by the time the three sides were finished, as the inscriptions on the fourth side were carved on the orders of his son, Ramesses II.²⁶ The obelisk adorned the temple at Heliopolis for nearly 1,000 years, until Egypt was invaded by the Persian ruler Cambyses II (559–530 BCE), who, according to the Roman author Strabo, ‘sought to outrage the temples, mutilating them and burning them on every side, just as he did with the obelisks’.²⁷ Strabo goes on to describe how two of the obelisks survived Cambyses’ fury and were brought to Rome. One of these was the obelisk quarried during the reign of Seti. Ammianus Marcellinus in his Rerum Gestarum describes how the Roman Emperor Augustus (63 BCE–AD 14), ‘brought over two obelisks from the city of Heliopolis in Egypt, one of which was set up in the Circus Maximus, the other in the Campus Martius’.²⁸

The Heliopolis obelisk of Seti was the first to make the perilous journey across the Mediterranean. On Emperor Augustus’ orders, the obelisk was shipped from Heliopolis to Alexandria in a similar fashion to its original journey 1,200 years before from the quarries of Aswan. The details of its transport across the Mediterranean are not known, although Augustus ordered the construction of a special ship for the purpose. The ship itself is not preserved, nor is any drawing or detailed description. In his Natural History, the Roman author Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79) merely states that, ‘the late Emperor Augustus consecrated the one [e.g. the ship] which brought over the first obelisk, as a lasting memorial of this marvellous undertaking, in the docks at Puteoli; but it was destroyed by fire’.²⁹ In Rome, Augustus’ craftsmen added an inscription to the base of the obelisk praising their emperor’s links to the divine Julius Caesar, and memorializing Augustus’ accomplishment of bringing Egypt under Roman control.³⁰

From Aswan to Heliopolis in 1281 BCE, from Heliopolis to Alexandria and from Alexandria to Rome more than 1,200 years later, this multinational monument was now raised at the Circus Maximus. It stood as a silent spectator to centuries of ludi: chariot races, religious processions and – until the construction of the nearby Colosseum in the late first century AD – gladiatorial combat. As Christianity rose to prominence and became the official state religion of the Roman Empire, the ludi fell out of favour and the Circus Maximus fell into decay. Flooding eventually toppled the obelisk and it was gradually buried in alluvial soil, lying undiscovered for nearly 1,000 years until it was unearthed at the height of the Italian renaissance in 1587. On the orders of the obelisk-obsessed Pope Sixtus V (1521–1590), the monument was re-erected by the Italian architect and sculptor Domenico Fontana (1543–1607)³¹ as the centrepiece of the Piazza del Popolo, where it remains to this day, encircled by street vendors and tourists soaking up the Italian sun.

A few broken fragments of granite and sandstone obelisks which once stood at the Temple of Heliopolis have also been found off the coast of Alexandria.³² They were most likely moved from their original location in a similar fashion to the Flaminian Obelisk during the Graeco-Roman period, and used to decorate one of several cities which once lay along the Delta’s northern coast before coastal erosion and rising sea levels flooded them.

However, some fragments of obelisk and a handful of life-size statues does not account for the ‘multitude of works’ which Seti decreed should be made during his reign. So where are the other granite monuments? Some scholars³³ have suggested that the relative brevity of Seti’s reign explains the paucity of granite monuments attributed to him. Seti reigned for eleven years, but the quarrying operations in Aswan were not begun until Year 9, two years prior to his death. The decoration of the Flaminian Obelisk was finished in the reign of his son, and it is reasonable to assume that other half-finished monuments were among his inheritance. Ramesses, who is particularly notable for his dedicated usurpation of the monuments of earlier rulers, was unlikely to have ordered such heirlooms finished in the image of his deceased father.

Particularly convincing examples of this usurpation of Seti’s legacy by his son are the two colossal statues of Ramesses II seated at the entrance to the Luxor Temple.³⁴ Both statues are carved from black Aswan granite, but with a curious unique feature: a vein of rose red granite has been employed to carve the crowns of both figures. This particular use of a natural vein of red stone is evidently deliberate and mirrors an order issued by Seti I in the Lesser Aswan Stela that colossal statues should be carved ‘of black granite whose crowns were to be made of red stone from the Red Mountain’.³⁵ The similarity is hardly a coincidence and suggests that the two colossal statues, traditionally ascribed to Ramesses II, were in fact quarried – but not finished – during Seti’s reign. As is so often the case, the deeds of Ramesses II helped to obscure the deeds and accomplishments of his father.

* * *

Merely building the temples themselves and decorating them with obelisks, stelae and statues was not, however, enough. Temples were complex economic institutions in their own right; they owned land, villages and fleets, merchants, mining rights and a vast array of resources secured by the king from foreign lands in the form of tribute or the spoils of war. Some of this extensive wealth enriched and empowered the priesthood, and some was used in a more direct way, as adornments for the images of the gods and goddesses held in the temple naos, or shrine. Gold was of course prominently used for this embellishment, as were precious stones like turquoise.

Yellow gold in particular is intrinsically linked to ancient Egypt in the modern psyche, no doubt due to the discoveries of many fine gold objects currently on display in museums throughout the world. But Egypt’s association with gold goes back far longer than Howard Carter’s famous description of the opening of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922: ‘[A]s my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold.’ Already in the twelfth century BC, King Ashur-Uballit of Assyria remarked upon the widespread usage of gold in Egypt in a letter he sent to Pharaoh Amenhotep III:

‘ I send as your greeting-gift a beautiful royal chariot outfitted for me, and 2 white horses, also outfitted for me, 1 chariot not outfitted and 1 seal of genuine lapis lazuli. Is such a present that of a Great King? Gold in your country is dirt; one simply gathers it up. Why are you so sparing of it? I am engaged in building a new palace. Send me as much gold as is needed for its completion.’³⁶

The peeved Assyrian ruler rather overstates the ease with which gold was mined in Egypt, although he was correct in his surmise that gold is not an uncommon mineral to find in Egypt’s eastern desert in particular. Gold is formed deep underground and forced to the surface encased in crystalline rock, usually quartz. By quarrying and crushing this matrix, the so-called ‘vein gold’ can be extracted, although time and water often eases the task by eroding the quartz matrix and leaving the more durable gold as small flecks in rivers or – crucially in Egypt’s eastern desert – where rivers used to run. The gold can then be collected by panning, a process whereby sediment is washed – or panned – to separate the lighter gravel and sand, leaving behind the heavier gold. Gold panning is made easier still by running the gold-bearing sediment across a sloping washing table overlain by a sheep’s fleece or similar fabric. Gravity and water will again wash away the lighter sedimentary elements, leaving the gold behind, caught in the folds of material or hair.

The Egyptians themselves recognized three sources of gold: the gold of Koptos, exploited primarily in and around Wadi Hammamat, Wadi Umm Awad and Wadi Mia in the eastern desert; the gold of Wawat, from Wadi Allaqi in Lower Nubia; and the gold of Kush, from Upper Nubia. While the Egyptians focused their energies and resources primarily on attaining control of the gold of Wawat during the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom pharaohs shifted much of their production back to the gold-rich wadis in the eastern desert near Koptos.

The mining operation itself was led by officials from specific temples, and manned by temple personnel, such as gold-washers and prospectors. Some evidence suggests that the backbreaking labour of crushing the gold-bearing quartz was conducted by prisoners-of-war or other captives, including women and children.³⁷ Once the gold was separated from the surrounding matrix by panning, it could be refined through melting in a crucible to remove impurities and then cast into gold rings for ease of transport. Raw gold from the eastern desert has a high level of naturally occurring copper and silver, which could not be effectively removed by the relatively crude refining practised by the Egyptians. This impurity of the gold caused, at least on one occasion, a diplomatic quarrel when King Burna-Buriash II of Babylon decided to test a gift of some 11.5kg of gold, which he received as a token of friendship from the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten. After refining the gold by melting it (alongside other, presumably more sophisticated methods than those employed by the Egyptians), Burna-Buriash was informed by his smelters that the actual amount of gold was less than 3kg – the remainder of the weight having been made up of various impurities – causing him to pen a missive, steeped in barely concealed fury, to the Egyptians demanding an explanation.³⁸

Like many kings before him, Seti eagerly despatched mining expeditions into the eastern desert in order to secure gold for his temples and royal estates. One of these expeditions travelled east from the ancient city of Koptos along the Wadi Hammamat, although its composition or the date of its departure are not known. Only small rock carvings in the wadi listing Seti’s cartouches and showing the king presenting offerings to the gods Min and Amun remain as a testament to their passing. More extensive evidence for mining operations during Seti’s reign can be found at Wadi Mia, a southern gold-mining area located east of the city of Edfu.

During the ninth year of his reign, Seti himself followed the track from Edfu in the company of the Overseer of Royal Workmen, a Troop Commander for Gold by the name of Anena and an officer from a ship named Appearing in Truth by the name of Nebseny,³⁹ alongside a company of stonemasons and – even though they are not specifically listed – no doubt assorted gold washers, prospectors and other workmen. As Seti traversed the parched desert landscape, he claims to have discovered and addressed an obvious provisioning issue:

‘ His Majesty had gone back and forth across a great distance. Then he stopped upon the road to plan together with his heart. Then he spoke: “How difficult is a road with no water created in it. How can travellers soothe their parched throats? Who can quench their thirst? The homeland is far away and the desert wide! Woe to any man who thirsts in the wasteland.”’⁴⁰

The expedition no doubt carried water containers on carts, but Seti did not consider this solution sufficient to support the kind of plans he had for the area, which included intensified mining activity and the construction of a settlement and temple. He scouted the land and summoned the sailor Nebseny, charging him with overseeing the construction of an artesian well, sunk directly into the bedrock. The well itself, which is preserved to this day, consists of a 49m-deep shaft near the modern goldmine of Barramiya in Qesm Marsa Alam.⁴¹

In order to commemorate his operations in the area, Seti ordered the construction of a rock-cut chapel, the Kanais Temple,⁴² close to the newly founded (most likely semi-permanent) settlement which housed the miners. The temple consists of a pillared outer portico which leads to three shrines. The central shrine was adorned with a statue of the king himself seated between the major deities to whom the temple was dedicated: Amun and Horus of Edfu. Other gods, including Osiris, Ptah and Re-Horakhty, adorn the secondary statue niches to the right and left. Isolated and protected from the weather and human vandalism, the temple decoration has survived astoundingly well, with the original colour still preserved on many of the reliefs and texts. The texts themselves comprise not merely an account of Seti’s visit to the site, his founding of the temple, the digging of a well and the foundation of a settlement, but also policy statements regarding the use to which the mined gold should be put:

‘ I have spoken thus about the organizing of the transport ship crews for the gold-washers at my Temple: They must give/deliver to my Temple [in Abydos, for the transporting of gold] for my temple.’⁴³

The statement is clear; all the gold mined at Wadi Mia was to be delivered to Seti’s new temple at Abydos, which was – towards the end of his reign – nearing completion, with only portions of the decorative scheme left to be finished. After the king’s command follows a long list of the horrifying punishments to befall any official who dared to contravene his orders, as well as a warning to future rulers who wished to tinker with his programme.

* * *

As Seti was preparing to go on his inspection tour of the gold mines in the eastern desert, another expedition had already set off from Egypt under the command of a royal envoy and troop commander named Asha-Hebused⁴⁴ bound for the Sinai Peninsula. It is likely that this officer led his crew, consisting of miners, soldiers and officials, through the Wadi Hammamat to the Red Sea before crossing the narrow strait to the Sinai Peninsula. Making their way across the el-Markha Plain, ascending onto the desolate el-Tih Limestone Plateau, the expedition arrived at one of the most isolated Egyptian outposts, the turquoise mines at Serabit el-Khadim.

The sight that greets a modern visitor is very similar to that which would have met Asha-Hebused and his men: a large, elongated temple ending in a sacred cave dedicated to Hathor and surrounded by hundreds of stela and rock-carved inscriptions listing the offerings brought by successive expeditions to the fickle goddess in order to court her favour. Asha-Hebused undoubtedly brought similar offerings with him: faience throw-sticks, feline and other animal figurines, pot stands and sistrums. The blue and green faience mimicked the more valuable turquoise and was thought to please the goddess, who was – after all – the patron of this stone, the ‘Mistress of Turquoise’. When the Hathor Temple was excavated by Flinders Petrie in the twentieth century, he recorded 2,792 whole or fragmented faience offerings, many decorated with the cartouches of New Kingdom rulers who sponsored missions to the site.

It was not only turquoise that attracted the Egyptian state to this remote outpost of its empire. Crucial deposits of copper – the core ingredient in bronze and other copper-alloys used to manufacture tools – were also found nearby at Wadi Maghara. A series of forts were already constructed on the el-Markha Plains from the Old Kingdom onwards⁴⁵ to secure the routes from the sea into the mountains, and to support and protect mining expeditions. Local nomadic communities exploited the rich mineral deposits before the Egyptians, and evidence from the Old Kingdom in particular suggests that the Egyptian attempts to monopolize the mines – rather than purchase the material from the nomads – caused unrest and even resulted in attacks on Egyptian garrisons in Sinai, prompting retaliatory raids by representatives of the Egyptian state. Aside from ventures at Serabit el-Khadim, Seti also sent expeditions to the copper mining camp at Timna⁴⁶ on the east coast of the Sinai Peninsula, although the evidence for this expedition is extremely limited. It may be that, due to the commonality of copper deposits along Egypt’s eastern desert, Seti did not consider it necessary to undertake the cost of sending large-scale expeditions to such a remote area.

* * *

Sandstone, granite, gold, turquoise and copper: the bones of the ancient Egyptian construction industry. During his reign, Seti either led or despatched missions to a wide-ranging selection of quarries and mines. However, despite the apparent disparate nature of the missions, a clear purpose lurks behind the edifice. The earliest expeditions, to the vast sandstone quarries at Gebel el-Silsila, were conducted by the second year of Seti’s reign. Given Seti’s desire to remove any remaining trace of the Amarna Period, and to a lesser extent the undignified political pushing and shoving that preceded it, one might imagine that Seti’s focus during the first years of his reign were on removing any offending monuments, along with the restoration of temples and chapels fallen into disuse.

After this first push for regeneration, and after winning his first victories in the Levant and putting the ancient world on notice that Egypt was once more ascendant, the next step was to begin the construction of his own legacy: at Karnak, Luxor, Heliopolis, Memphis and, in particular, at Abydos. This required raw building material, and it was for this purpose that the missions to Gebel el-Silsila, and also to other sandstone and limestone quarries throughout the land, were despatched. While the feverish building programme continued throughout his reign (evidenced for instance by the second mission to Gebel el-Silsila in Year 6 of his reign), other projects had entered a second phase: the shells of their buildings were completed, and the artists and stonemasons were now going to work on the decorations which would adorn them. For those, the artists needed, and the king demanded, the Aswan granite. This was secured by Year 9 of his reign, and the work began on the manufacture of stela, obelisks and colossal statues, sadly curtailed by Seti’s untimely death two years later.

It is tempting to see the expeditions to Serabit el-Khadim, Wadi Hammamat and Wadi Mia within this framework. These missions for turquoise and gold were also undertaken later in Seti’s reign, and their purpose was surely both to secure material for the manufacture of cultic equipment for the new temple institutions, and also – along with the spoils of war Seti brought back from his Levantine adventures against Amurru and the Hittites – to enrich the priesthood and the state. Missions to copper mines, along with the import of copper from Cyprus, were certainly a constant throughout Seti’s reign, given the amount of tools required for his ambitious building programme, which came to cover the length of the Nile Valley.

* * *

Among the multiplicity of religious structures which benefitted from royal patronage during Seti’s reign, none is more awe-inspiring than the Karnak Temple located near the modern town of Luxor in Middle Egypt. Known as Ipet Sut (‘Holiest-of-places’) to the ancient Egyptians, this vast complex was a focal point for the worship of Amun and his Triad during the New Kingdom. Given Amun’s de facto role as ‘chief god’ at this time in Egyptian history, expanding and decorating his temple became a keystone policy for most New Kingdom rulers. At the time of Seti’s ascension, the Karnak religious complex was composed of three individual temples; the Precinct of Amun and the smaller temples dedicated to his mistress, Mut, and his son, Khonsu. Covering more than 250,000m², the Precinct of Amun alone is large enough to contain St Peter’s Basilica in Rome more than seven times over.

The Karnak complex came from humble origins. During the Old Kingdom, possibly as early as the 3rd Dynasty,⁴⁷ the city of Thebes was merely a regional capital. Its peripheral position changed with the decentralization of the First Intermediate Period and it gradually rose to prominence as one of two power centres in Egypt: Herakleopolis in the north and Thebes in the south. As part of the expansion of the settlement under the local ruler Intef II, a small mud-brick chapel decorated with inscribed sandstone columns was built to honour the local god Amun.⁴⁸ When Intef II’s grandson, Nebheptetre Mentuhotep II, reunified Egypt, this local Theban deity attained national status. After the death of Mentuhotep IV, his successors Amenemhat I and his son Senwosret I lavished more attention on the Temple of Amun at Thebes in an attempt to legitimise their reign by demonstrating a connection to the Theban royal family. Loyalty to the old family’s deity of choice became an effective substitute for an actual connection by blood. Senwosret I ordered the construction of a small chapel in white limestone, inscribed with scenes showing himself being crowned by some of the most prominent deities in the Egyptian pantheon: Amun, Min, Horus and Ptah. The chapel was unceremoniously demolished 600 years later by Amenhotep III and the fragments used as construction fill for the Third Pylon. In the late 1920s, the pieces were carefully excavated by archaeologists and the chapel was reassembled and opened to the public.⁴⁹

The arrival of the Hyksos in northern Egypt sparked the Second Intermediate Period and Thebes again became the headquarters of the Egyptian culture and the royal family. After the expulsion of the Hyksos, the early New Kingdom rulers credited Amun with granting them victory against their enemies and embarked on one of the most expansive and far-reaching construction projects in world history. As a direct result of the importance these pharaohs ascribed to Amun and his temple, almost every ruler until the Roman invasion of Egypt more than 1,400 years later would in some way, great or small, endow or expand the Karnak complex in general and the Precinct of Amun in particular.

Amenhotep I, Thutmosis I and Thutmosis II all added to the structure, and when Hatshepsut ascended to the Horus Throne of the Living, it was fronted by two large mud-brick pylons, clad in inscribed and decorated limestone. Hatshepsut continued her predecessors’ building activity at the site, raising obelisks, ordering the construction of an additional pylon and constructing a barque shrine in red quartzite, commonly known as the Chapelle Rouge. The shrine served as a rest stop during the Festival of Opet when the cult images of Amun, his consort Mut and son Khonsu journeyed on sacred barges to the nearby Luxor Temple and back along an avenue of sphinxes. In an act of damnatio memoriae, Hatshepsut’s son, Thutmosis III, would see most of her contributions to the architectural landscape at Karnak either usurped or destroyed.⁵⁰

The long and prosperous reign of Amenhotep III saw even more royal attention and resources lavished upon the Karnak Temple and its priesthood. The king not only expanded the Precincts of Mut and Khonsu, but also finished an additional pylon (the fourth pylon), begun by Thutmosis II and Thutmosis IV but left unfinished. In a somewhat curious reversal of objectives, he ordered this pylon torn down later in his reign, the building materials instead used to build a brand-new pylon (the third pylon). Amenhotep also raised a colossal quartzite statue of himself standing 20m tall.

With the ascension of Amenhotep IV, and in particular when he elected to eschew the name of Amun from his own and change it to Akhenaten, the Karnak Temple fell out of royal favour. Rather than build to glorify Amun and his sacred triad, Akhenaten constructed the Gem-Pa-Aten,⁵¹ a temple dedicated exclusively to the Aten sun-disk immediately north of the Karnak enclosure. With the end of the Amarna Period and the reigns of Tutankhamun, Ay and Horemheb, this structure was comprehensively destroyed and these restoration pharaohs returned to adding new architectural features to the Karnak Temple and resuming the donations of resources and manpower to the Amun priesthood. Horemheb, for instance, added two more pylons (the second and ninth pylon) during his reign. As Seti took over from Ramesses I, the Karnak Temple comprised seven pylons, several decorated courts, including the so-called ‘Wadjet Hall’ constructed during the reign of Hatshepsut, and a separate temple for the Theban god of war, Montu, built on the orders of Amenhotep III.

Seti, however, had more ostentatious visions for Karnak than just adding yet another pylon. Early in his reign, possibly as early as Year 1, he began planning for the grandest of all his architectural legacies. In between the third pylon of the temple, built during the reign of Amenhotep III, and the second pylon, begun by Horemheb but finished by Ramesses I, he ordered the construction of a vast hypostyle hall. In architectural terminology, a hypostyle merely describes a room with a roof supported by columns. This rather clinical definition hardly conveys the overwhelming splendour of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak.⁵² An area of more than 5,000m² inbetween the second and third pylon was covered with a wooden roof. The roof was supported by 134 carved and inscribed limestone columns, the largest of which are 10m in circumference and stand 24m tall. The hypostyle hall can be entered from four points; either through the mud-brick and limestone pylons or via gateways in the north and south walls of the hall.

Early scholarly opinion⁵³ held that Seti did not conceive of the hypostyle hall himself, but merely finished work already begun by Amenhotep III and interrupted by the reign of Akhenaten and the chaotic aftermath of the Amarna Period. The primary evidence in favour of this argument – that a foundation level of sand under the third pylon built by Amenhotep III extended under parts of the hypostyle hall – was, however, more recently shown to be erroneous.⁵⁴

While the Karnak complex was undoubtedly the most important religious structure at Thebes, it was not the only one. Luxor Temple, which lies 2km south of Karnak, was an integral part of the sacred landscape of the settlement, especially during the Opet Festival when the semi-divine kingship of pharaoh was reaffirmed in the innermost sanctums of the temple. While most of Seti’s new construction activity focused on Karnak, he also embarked on a campaign of restoration of monuments at Luxor soon after his ascension.⁵⁵ Amenhotep III had left substantial architectural and decorative elements unfinished there upon his death, including a colonnade hall, the hypostyle hall and several stelae and offering tables. Many of these monuments had not only been left to fall into disrepair, but had been actively attacked and defaced during the Amarna Period. Feeble attempts at restoration by Tutankhamun, Ay and Horemheb had not done much to alleviate this wretched state of affairs. Instead, it was left to Seti to finish the decoration of the colonnade hall. Several smaller pieces of sculpture made on the orders of Amenhotep III and defaced by Akhenaten’s followers were also delicately restored, their carvings reproduced along their original lines.

Upon Seti’s death, his son Ramesses continued his father’s legacy at the Karnak Temple. He completed the last of the columns in the Great Hypostyle Hall and ordered several of the war reliefs recarved, inserting himself into scenes where he was not originally found. But while the hypostyle hall arguably represented one of Seti’s most striking architectural visions, it was far from the only one.

* * *

Located 12km north of Tahrir Square in central Cairo is the cramped neighbourhood of El Matareya. Standing vigil above the crowded streets, with fruit-sellers offering their wares from the back of pick-up trucks, and shouting to be heard above the near-constant car horns, is the red granite obelisk of the Middle Kingdom ruler, Senwosret I. Under the feet of the pedestrians, buried deep under layers of modern concrete, sherds of glazed Ottoman pottery and Roman marble lies the remains of the ancient city and temple of Heliopolis, home to the cult of the sun god Re from the Old Kingdom onwards. What remains of the temple enclosure is increasingly under threat from encroachment of modern rubbish deposits and the spread of urban architecture onto the archaeological site.⁵⁶ These destructive factors have rendered much of the evidence from the site fragmented and difficult to interpret. Little remains now, aside from the so-called ‘High Sands of Heliopolis’, a large mound which lay at the centre of the mud-brick enclosure that made up the temple. Recent excavations in this area have confirmed the presence of monumental architecture, including a red granite statue of a king and a lintel of Ramesses II. Along with Amun at Karnak, Re (or Re-Horakhty) of Heliopolis was a crucial deity, and intrinsically linked to royalty and the power of the king. Heliopolis was also home to a temple dedicated to Atum, one of the original creators of the world.

According to the Heliopolitan Cosmogony, or creation story, Atum was present within the primeval waters of Nu, where he caused a pyramid-shaped mound of sand called benben to rise from the waters and, using his hermaphroditic characteristics, Atum masturbated and ‘birthed’ the god of the air, Shu, and his sister Tefnut. They mated and produced the earth god Geb and his sister, the sky goddess Nut, who in their turn created the world. Geb and Nut produced four children Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys who populated the world with gods and people alike. The mound which lay within the temple enclosure at Heliopolis was believed to be a representation of the benben, and therefore the very place where the world began. Re, the sun god, was also instrumental in the creation of the world, and at Heliopolis, Re and Atum were intrinsically linked, sometimes even referred to as a single deity: Re-Atum.

Given the religious significance of Heliopolis, Seti was naturally keen to lavish attention upon the temple. Seti codified his vow on the Flaminian Obelisk in Rome, where the king is described as one ‘who fills Helioplis with obelisks like shining rays, with whose beauty the Domain of Re is overflowing’.⁵⁷ As discussed elsewhere in this chapter, the granite and sandstone obelisks which Seti raised at Heliopolis are no longer found in situ. Through the actions of the Roman governors and emperors of Egypt, they were scattered, some to Alexandria and onwards to Rome, others to a long rest on the bottom of sea near the fifteenth-century Citadel of Qaitbay in Alexandria.

While nothing of Seti’s renovations and various building projects at Heliopolis remain visible today, a model of the temple gateway at Heliopolis⁵⁸ nonetheless provides a useful clue for how it would have appeared. The model was found by local farmers at the site of Tell el-Yahudiyah in the Nile Delta before the first archaeological excavations of the area were conducted by Edouard Naville in 1890. The model was bought by the Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund and gifted to the Brooklyn Museum in New York, where it resides today. Carved in red quartzite, the model shows a rough approximation of the entrance pylon to the temple of Heliopolis during the reign of Seti I. Holes in the stone show where small-scale models of additional architectural elements could be placed, although these have long since vanished. However, noted Egyptologist Alexander Badawy⁵⁹ studied the remains of the model and reverse-engineered a reconstruction of how it would have appeared when it was deposited, most likely as a ritual offering, in the ground either at the Ramesside Temple at Tell el-Yahudiyah or at Heliopolis itself. His reconstruction shows the pylon fronted by two large black granite obelisks, one of which was almost certainly the Flaminian Obelisk now in Rome. It also shows three sphinxes, similarly carved from black granite, fronting the causeway leading to the temple gates, as well as a colossal statue. Aside from the Flaminian Obelisk, it is not known where the sphinxes or the colossal statue can be found today, but it is possible that they still lie undiscovered under the pavements of El Matareya. Another possibility is that Ramesses II usurped his father’s monuments, or that – like the colossal statues at the Luxor Temple – he inherited half-finished statuary and ordered it inscribed with his own name rather than that of his father.

Heliopolis was not the only site where Seti’s contributions to the sacred landscape have been lost. Immediately to the south, at the site of Mit Rahinah near modern Cairo, Seti ordered the construction of both a new temple dedicated to Ptah, the patron of Memphis, and a smaller limestone chapel similarly dedicated to Ptah, accompanied by Mennefer and Tjesemet, two goddesses who personified the city of Memphis itself.⁶⁰ Due to stone quarrying in antiquity, agricultural and urban encroachment, along with a lengthy campaign of antiquity looting, only a few scattered sculptural fragments of Seti’s Memphite legacy remain to be seen today.

* * *

Few sites in Egypt, even the great Karnak complex, have as significant a place as a cultic centre for the duration of the Pharaonic civilization as the site of Abydos in Middle Egypt. Located near the modern village of el-‘Araba, occupation of the area dates far back into Prehistory, with the site already holding significant importance as a royal burial ground by the Early Dynastic Period. The rulers of the 1st and 2nd Dynasties were buried at Umm el-Qa’ab, their tombs accompanied by the construction of mortuary temples surrounded by large enclosure walls, known as ‘forts’. During the Old Kingdom, a settlement and associated religious structures grew at nearby Kom es-Sultan⁶¹ and the site developed even greater importance as local god, Khentimentiu, the ‘Foremost of the Westerners’, became associated with the deceased king. By the early Middle Kingdom, Khentimentiu had become linked to Osiris, the Ruler of the Underworld, and this link more than anything cemented the significance of Abydos. The first ruler of Egypt during the Middle Kingdom, Mentuhotep II, entirely rebuilt the Great Osiris Temple at the site, and this structure was further expanded by the first ruler of the 12th Dynasty, Senwosret I, and by many subsequent kings.

One of the most significant rituals associated with the worship of Osiris at Abydos was the ‘Osiris Mysteries’. These took the form of an annual festival where an image of the god was carried on a gilded barge from his temple at Abydos itself into the desert at Umm el-Qa’ab. There, the 1st Dynasty tomb of King Djer (known as Ta Peqer or ‘Sacred Land’) had become confused for the tomb of Osiris himself in the Egyptian collective memory. The specifics of the Mysteries are not clear, but a stylized battle against the enemies of Osiris, led by his brother Seth, took place before the statue was returned to the temple. While the rituals in the desert were hidden from profane eyes, the procession itself was most likely a public spectacle, with the inhabitants of the nearby towns⁶² and dignitaries from the court lining the processional route. The procession became so significant in the minds of the Egyptians that thousands upon thousands of cenotaphs were constructed along the processional route, where stela and statues of deceased family members could be placed so that, even in death, they would still be able to view the Mysteries and benefit from the offering cult managed by the Osiride priests.

Given the significance of Abydos as a centre of the Osiris cult, and the status of Osiris himself as Ruler of the Underworld, it is little wonder that Seti chose to lavish attention upon the site for the entire duration of his reign. Seti’s most significant contribution to the sacred landscape at the site is undoubtedly the great temple,⁶³ dedicated to Osiris, which he constructed south of the Great Osiris Temple that had stood, in various incarnations, since at least the Old Kingdom. The purpose of Seti’s temple was not so much to honour Osiris; rather it functioned as a memorial temple for Seti himself, and also for the pharaohs who had gone before him. In this way, the function of the structure has more in common with the mortuary temples built by New Kingdom kings on the Theban West Bank than with structures such as the Precinct of Amun at Karnak.

It is not known precisely when Seti ordered the construction of the temple to begin, but it was most likely in the early part of his reign. By Year 4, the structure was sufficiently complete to begin its function; it was (partially) equipped with priests and donations,⁶⁴ although construction work certainly continued. A visitor to the temple at the time of Seti’s death would have been greeted by a monumental pylon, which was yet to be decorated. This task was undertaken later in the reign of Seti’s son, Ramesses. The gateway through the pylon led to an outer court, which contained two artesian wells sunk into the limestone bedrock, their water most likely used for ritual cleansing and the pouring of libations within the temple. A portico which had been roofed but not yet fully decorated led to a second court, which in turn led to two hypostyle halls. While not as impressive as the Great Hypostyle Hall in Karnak, the walls themselves were decorated with unsurpassed raised relief showing the pious king prostrate in front of a variety of deities, along with scenes showing the foundation of the temple itself and others related to the proper function and progression of kingship; the latter is a theme which is recurrent through the structure. This is understandable, given the non-royal birth of Seti and his need to legitimize his rule.

Seven smaller chapels lead off from the hypostyle halls, the central one of which is dedicated to Amun-Re. The first shrine in the sequence was naturally dedicated to Seti himself, with the gods Ptah, Re-Horakhty, Osiris, Isis and Horus representing the remaining five shrines. The decoration in the hypostyle halls and the shrines is interlinked and related to the proper conduct of the daily ritual for each of the individual gods, along with the conduct of their religious processions. South of the chapels is an annexe which contains one of the most significant historical documents from Seti’s reign: the ‘Gallery of Lists’. On the walls of this narrow corridor, Seti ordered a comprehensive list of all rulers of Egypt to be preserved for eternity. The list has some obvious failings; it is not an unbiased account, and rulers whom Seti did not think were worthy were simply left off. There is no Akhenaten, no Hatshepsut,⁶⁵ nor even Ay or Tutankhamun. The entire Amarna Period was effectively airbrushed out of history. The gallery is also notable for its depiction of Seti’s successor, Prince Ramesses, shown as a young boy standing behind his father. This relief was carved during Seti’s lifetime and shows that Ramesses was already then held in high regard, understandable given that he was Seti’s eldest son. The two are also seen together lassoing a wild ox, a symbol of Egyptian kingship, in the nearby Bull Corridor.

The most extensive memorialization of a royal ancestor built by Seti at Abydos was the small Chapel of Ramesses I.⁶⁶ Standing within its own small enclosure, this limestone chapel was dedicated exclusively to the memory of Ramesses and contains some of the most exquisite reliefs of Seti’s reign. Many of them show Ramesses and Seti together, offering to the gods of Abydos, Osiris, Isis and Horus, along with extensively detailed scenes of bearers carrying offerings for the ka of the deceased Ramesses. The texts inscribed on the chapel walls take the form of a dialogue in which Seti lists the actions he has taken as a dutiful son to his father, and Ramesses answers by assuring his son that the gods have ordained his right to rule: ‘I have heard their speech; they have decreed the throne of Atum and the years of Horus, as protector. They give to you this land by testament, and the Nine Bows are captured for you.’⁶⁷

In an accompanying inscription carved on a large dedicatory stela, Seti relates how his father ascended to the throne after being directly chosen by Amun-Re, the Lord-of-All. The text goes on to describe how Seti was nurtured and taught by his father’s example: ‘It was he, indeed, who created my beauty; he made great my family in (people’s) minds. He gave me his counsels as my safeguard, and his teaching was like a rampart in my heart.’⁶⁸ While the inscriptions doubtlessly had a political function, it is nonetheless tempting to see true emotion in those words and the beauty of the accompanying inscriptions, especially considering the paltry tomb Seti was forced to bury his father in due to Ramesses’ short reign.

Adjoining the Temple of Seti is a series of mud-brick magazines, used for the storage of offerings, as well as a small palace to house the king and his officials when he visited. Behind the temple, by the western enclosure wall, is a curious structure known as the Osireion. It comprises a simple stone hall with a raised platform and square pillars. Built at a lower level than the rest of the structures, the Osireion is prone to flooding, which has made significant archaeological work troublesome. While the common belief is that the Osireion functioned as the tomb or grave of Osiris, a far more realistic explanation is that it was in effect a cenotaph for Seti I, or perhaps Seti-Osiris, that is the king in his form as the Ruler of the Dead. Egyptian royalty had built cenotaphs at Abydos for millennia, so that while their bodies were buried at Saqqara, Dashur or the Valley of the Kings, their spirits had a home in Abydos and could receive nourishment from the daily offering rituals conducted by groups of priests dedicated specifically to the maintenance of the royal ka.

The Osireion, and the temple structure as a whole, was built from limestone brought from a nearby quarry, first overland and later by boat through a canal. The Osireion also contains elements of sandstone, almost certainly from the quarries at Gebel el-Silsila. Discovered by Flinders Petrie during his work at Abydos in the early twentieth century, the Osireion was both excavated and published by a trail-blazer in the field of archaeology, Margaret Alice Murray (1863–1963).⁶⁹ Working as one of the first female excavators in Egypt, Murray expertly recorded the Osireion after training with Petrie himself. She published her findings as The Osireion of Abydos, a book which has greatly informed much of the later work at the site.

When the temple was fully operational, it commanded an army of human resources, from the High Priest to fowlers, herdsmen, farmers and the crews of merchant ships. The wealth generated by the temple was channelled into the offering cults conducted at the site, including the memorial cult of Seti I himself. It was therefore much in the king’s interest to ensure that no one tinkered with the economic endowments he had granted to his new temple. To combat such back-sliding, Seti ordered a large decree carved in Nubia near the town of Nauri, north of Dongola in modern-day Sudan. The decree contains the customary laudations for Seti himself, his piety, his great acts in war and his predestined right to rule, but the text also provides a detailed list of the appropriate punishments for various acts of vandalism or criminal activity against Seti’s Temple at Abydos, its staff or resources. It bans anyone, including high officials and members of the military, from attempting to forcibly recruit or conscript any man or woman who works for the temple, on pain of being beaten with 200 blows and given five open wounds as punishment. The punishment for tampering with field boundaries is even harsher: the forced amputation of both nose and ears and demotion to field labourer.

The resources invested in its construction and maintenance, along with the harsh rhetoric of the Nauri Decree, shows the significance Seti ascribed to his temple at Abydos. As a memorial temple, it would function in tandem with his planned mortuary temple at Qurnah in Thebes and ensure that his ka was provided for in perpetuity, so that the king could experience an eternal, happy afterlife in the Fields of Reeds, in the realm of Osiris. Seti would not, however, live to see his great work finished. The honour of completing the monument was left, as was the case with so many of Seti’s architectural contributions to Egypt’s sacred landscape, to his son, Ramesses II.

Excursus: Piety or Politics?

Expanding and enriching the sanctuaries of the gods was a paramount duty of the Egyptian pharaoh. Along with defeating and conquering Egypt’s foreign enemies, the construction of great temples was seen as a sign of the proper running of the world. Destruction or abandonment of temples was not simply a sin, but a sign that the world had turned upside down and that proper societal rules had been suspended. This sense of the correct order was the cause of the immediate restoration work undertaken by the successors of Akhenaten: Tutankhamun, Ay and Horemheb. They were desperate to reverse the centralization of their predecessor and his neglect of the various centres of traditional worship throughout Egypt, in particular the great Karnak Temple in Thebes. While Horemheb in particular successfully undertook much restoration and construction during his reign, the scale of Seti’s construction ambitions were unrivalled since the reign of Amenhotep III.

Seti’s obsession with construction and endowments of temples led scholars to construct an image of Seti as a man of ‘admirable piety’,⁷⁰ a king possessed of both grace and humility in the face of the divine. An artistic change in the representation of the figure of the king in reliefs during his reign further contributed to this image: rather than standing upright in front of the gods, an equal in every way, Seti is often shown humbling himself, kneeling or even prostrating before the gods in a show of abject humility. Only Amenhotep III was shown as frequently in a similarly bowed position, in particular during the latter part of his reign.⁷¹ Seti was clearly inspired by these expressions of piety shown by his successor, although he greatly extended their use. At the end of his reign, the kneeling and prostrate positions were abandoned by Ramesses II, who seemingly felt that he had no need to show such humility.⁷²

So should the large-scale temple construction and the depictions of Seti humbling himself before the gods be taken as a sign of his pious nature? Not necessarily. As Gardiner⁷³ noted, the construction of temples was an intensely political undertaking. By linking himself to the grand constructions of Amenhotep III, the last ruler before the Amarna heresy, Seti propagated the notion of a direct link between himself and the greatest ruler of the previous dynasty, even though no blood ties whatsoever existed. It cannot, however, be completely discounted that the time of religious turmoil and confusion in which the king grew up had an effect on his personality, and that as a result he was filled with a type of religious fervour, but there is little in the way of evidence to support this notion. The most sensible interpretation is perhaps that politics and personality combined as motives in the mind of the king, and together instigated one of the most extensive construction projects in Pharaonic history. From Nubia in the south to the Delta in the north, Seti’s architectural legacy spans the length of the Nile Valley, and – had it not been for the uncommonly long reign of his son, and the advantages Ramesses gained from Seti’s legacy – he would undoubtedly have been remembered as one of the greatest builders in human history.