Human societies are held together by relationships, conventions, traditions, institutions, and tacit understandings. These things are intangible, and while humans themselves are reproduced as corporeal beings, their societies are sustained by practical activities that continually recreate knowledge, customs, and interpersonal bonds. Just as a language would ultimately disappear if it ceased to be used as a means of communication, so the rules and routines of social life are maintained only if they are practised. The corollary of this is that societies are not fixed and bounded entities as much as arrangements that are continually coming into existence, works (if you like) that are never completed. But material things are also in flux, constantly ripening, maturing, being made, being used consecutively in different ways through their ‘lifespans’, eroding and decaying: so that the social and substantial worlds are as one in being in an unending state of becoming. Nonetheless, objects often have the capacity to endure longer than habits, rules, or affiliations. They continue to exist independently of human beings and their actions. As a result, old artefacts and places occupied in the past can serve to give structure to current practices and transactions, providing cues and prompts, or reminding us of past events and appropriate modes of conduct.

Hunter-gatherers have generally lived a way of life that involves making continual reference to natural features and landmarks. Certain distinctive cliffs, hills, islands, trees, and lakes have represented places to return to, or at which to arrange meetings or encounter game. As such they will have been places of periodic resort, and were incorporated into collective history and mythology. Meanwhile, other places acquired a meaning simply because specific people camped there, or met there, or died there. During the Mesolithic in Britain, some locations seem to have been persistently returned to over very long periods of time. One example is the site at North Park Farm, Bletchingley in Surrey, which appears to have been visited sporadically over hundreds of years, although the structural evidence for this at the site was sparse, being limited to a group of fireplaces. Similarly, the middens composed of marine shells and other materials found in coastal areas, particularly in the west of Scotland, were locations that people reoccupied at intervals and used for a variety of activities, including the manufacture of tools from animal bones and the processing of human remains. The way that these places gradually became established as focal points in the landscape would have lent a degree of consistency and predictability to the rhythms of everyday life.

All of this changed subtly with the start of the Neolithic. The material world that people inhabited abruptly began to contain more artefacts and more structures crafted by people. While hunter-gatherers had minimized the material equipment that they carried with them in order to facilitate mobility, Neolithic people had new kinds of object that enabled them to organize their activities in newly distinctive ways, or to express their relationships and identities anew. The first use of pottery meant that foods both old and new could be stored, cooked, and served in novel ways, while the possession of polished stone axes exchanged over long distances were an immediately recognizable indication of a person’s status. Equally, timber halls, long mounds, and, later on, causewayed enclosures provided new settings that gave a distinctly novel structure to encounters, tasks, and observances, while features such as the timbered linear Sweet Track in the Somerset Levels defined patterns of movement through the landscape, even if temporarily, and even though in some cases these routes may already have existed more informally before they were marked in this manner. In a variety of different ways, these new artefacts and a more architectural punctuation of space reduced the need for lengthy deliberation in social life, potentially rendering more of people’s activities habitual and unconsidered. Where actions and transactions are repeated while reducing the need for explicit consideration, social relationships can acquire a greater degree of stability. There could be less fissioning of groups prompted by the vicissitudes of the movements of game or year-on-year variation in the availability of wild foods. People did not necessarily need to debate and evaluate their every move, and the richer world of crafted things that the Neolithic offered would have had the effect of entrenching patterns of practical activity that may have contributed to a comparative fixity of social arrangements.

Hunter-gatherers often have had a way of life that combines fluidity and flexibility of living arrangements with extensive networks of mutual aid and support. Bands of people have congregated and then split up seasonally or according to circumstance, and have had to share whatever they possess to ensure mutual survival. But with the adoption of domesticated plants and animals came the possibility of creating distinct and bounded social groups who had collective ownership over herds, seed corn, and land, but whose use of those resources was (or could be) exclusive to those groups. Such a changed relationship to the means of subsistence was the product of a novel investment in those resources, in terms for instance of the management of herds, or the forethought required to plant and the need to protect those crops. And these people had to have made the investment in time and energy and seed-stock to sow them in the first place. The owners of these resources are the ‘invested lineages’ that we have already mentioned. We should not simply assume that it was the availability of new resources that created a shift to a more structured social order: rather, such a social order is equally likely to have been a prerequisite for a subsequent shift to herding and cultivation.

To look at the same issue from a different perspective, we can note that archaeologists often presume that the elaborate material culture of the Neolithic was effectively a set of luxuries that was made possible by the more productive economy offered by farming. The reverse may in fact be the case: the more channelled, extended, and formalized social practices of the Neolithic provided the necessary stability and definition for an ever-increasing dependence on domesticates. As we have seen, John Robb has perceptively argued that while it would have been relatively easy for hunter-gatherers to become entangled in this new world of pots, axes, tombs, houses, and gardens, it would have been much harder for them to extricate themselves. This, again, was presumably also a matter of having made the novel investment in breeding, stock-management, sowing, watering, and harvesting (for example), which became difficult to abandon without a palpable measure of loss. For this reason, few communities ever reverted to a Mesolithic way of life, and the tendency was for the Neolithic lifestyle to proliferate over time.

The Neolithic communities of Britain were pre-literate, and were non-state societies. They obviously lacked the institutions that sustain order in the modern world: government, legal systems, education, armed forces, finance, and the media. In their absence, social relationships and shared knowledge had to be continuously maintained through the performance of traditional practices, anchored in the material world. While acts and ideas are continually emerging, their habitual reiteration may render them as routine and conventional, and this process was facilitated in Neolithic times by the creation of a durable framework of artefacts and structures, which guided and constrained everyday activities. Neolithic groups were ‘traditional societies’, in the sense that understandings of the world and ways of doing things were passed down from one generation to the next, and, as we will see in Chapter 6, the consequence of this was that past generations remained a powerful presence among the living. Cultural memory, shared history, and collective ancestry maintained potent connections with the past. Many of the practices that we will discuss in this chapter contributed to the stabilization of social life. For instance, herds of cattle had a temporality (in other words a series of inbuilt relationships to elapsing time and cyclical events) and a momentum of their own, and as such maintaining the herd lent a necessary stability to each human group that tended them. But as we shall see, the roles of kinship and descent in this self-sustaining of the Neolithic world were of critical importance.

Working and extracting flint

At various places in this book we will imply that the contemporary Western conception of matter as inert, inanimate, and passive is unlikely to have obtained during the Neolithic. Ethnographers have observed that in many societies, substances and materials are conventionally understood as being imbued with forces, and with potential capacities, often being viewed as having a dynamic role to play in the workings of the human social world. Inevitably, chipped stone technology remained of fundamental importance during what we term the ‘New Stone Age’, but it may be unwise to consider it in purely mechanistic terms. Working flint and other rocks which upon striking produce a conchoidal fracture requires the application of force to detach removals (waste flakes) from a surface. This activity demands an engagement that is intensely physical and reactive, and in which the artisan continually turns the block of stone over in their hands, identifying the right place and angle from which to strike it. Almost certainly, this activity would not have been perceived in terms of the imposition of an abstract and preconceived template onto the material, as has sometimes been assumed by archaeologists. Rather, ethnographic testimony gathered among the Australian First Peoples, for example, suggests that it is likely that it was the immanent potential of the stone, hitherto locked within a ‘raw’ flint nodule or stone block, that was being released through the striking action, setting free the flint or stone blade or axe, or the flint or chert scraper or knife that was perceived to be slumbering in the nodule or block.

If the knapping of flint and the working of stone involved more than the routine stamping of form onto matter, the interaction with the protean forces embodied in these materials is likely to have been seen as a powerful event in itself. An indication of this may be represented by the ‘nests’ of flint flakes sometimes found in the ditches of earthen long barrows and cursus monuments (see Chapter 4). The explanations that have been offered vary from the possibility that the base of a ditch offered a comfortable place to work flint, sheltered from the elements, to the notion that nodules encountered during ditch-digging may have been ‘tested’ to ascertain their utility for tool-making. However, in some cases the flint nodule had been knapped until nothing remained beside the mass of flakes, with few tools, or even none at all, having been produced. During an excavation of the western terminal of the Greater Stonehenge Cursus conducted by one of the authors in 2007, numerous groups of flint flakes were encountered throughout the primary silting of the ditch. This demonstrated that the knapping had taken place over a period of months or years, and not solely at the time of ditch-digging. We suggest that in these circumstances, as much as the production of tools, the act of knapping can be identified as a process that released the potency of the material into its environs, thereby contributing to the creation of the monument’s distinctive identity or efficacy. Alternatively, or perhaps complementarily, the expenditure of the potential of a flint nodule that might otherwise be used to form ‘useful’ artefacts could have represented in its own right a dedicatory act, a gift to the gods, spirits of place, or ancestors. This was perhaps either to appease the disturbance of opening up the ground, or to give thanks for the successful execution of the project of building the structure or monument.

One of the most notable developments in the working of stone during the Neolithic was the appearance of flint mines with deep central shafts and, wherever seams of prime-quality flint nodules (known as floor-stone) were encountered, radial galleries. These were neither a feature of the Mesolithic, nor of the earliest Neolithic in north-west Europe, but are first observed in the Low Countries, southern Scandinavia, and the Upper Vistula at around the same time as the beginning of the Neolithic in Britain, or a little earlier. Such is the scale of investment in digging shafts down through ten metres or more of chalk to encounter tabular flint, that mining has routinely been seen as evidence for the beginnings of an industry in the contemporary sense. This characterization is almost certainly misleading, implying as it does the mass production of utilitarian commodities. Throughout the Mesolithic, flint had been acquired from surface exposures on beaches, in river gravels, and on the clay-with-flints, often accessing high-quality raw material for items such as ‘tranchet’ axes (with a transverse rather than symmetrical blade). As described in Chapters 2 and 3, shortly after 4000 bce deep flint mines began to be dug in the area of the South Downs immediately to the north of modern Worthing in Sussex. Like the other near-contemporary European sites, the mines occurring at intervals close to the crests of these hills at Cissbury, Harrow Hill, Blackpatch, and Church Hill, Findon, appear to have been concerned primarily with the manufacture of roughed-out and polished flint axes. While the modern geochemical sourcing of flint remains in its infancy, there are indications from macroscopic inspection of the glassy cryptocrystalline silex core of struck flakes that axes with a milky opaque matrix from Sussex were widely distributed in Britain during the earlier part of the Neolithic. So the earliest flint mines in Britain were primarily concerned with the manufacture of a rather special kind of artefact, and their status as amongst the very earliest Neolithic sites in the area suggests that the first digging of these mines was intimately connected with the beginning of the process of Neolithization in Britain. The practice of flint-mining was undoubtedly introduced from the Continent, but certain details suggest that distinctive elements were immediately added. Most markedly, this involved the use of red deer antlers as the main extractive tools, in contrast to the use of stone tools in Belgium, as we have seen.

As we noted in the Introduction to this book, alongside the houses at Skara Brae and the chambered interiors of some long mounds, flint mines offer us the rare opportunity to come close to a personal ‘three-dimensional’ experiencing of the Neolithic in Britain. They represent a remarkable form of architecture, which served to structure both the process of extraction and the interpersonal relationships of those involved. In common with other aspects of the Neolithic material world, flint mines contained and regulated human activity, channelling movement and establishing habitual ways of working. As Mark Edmonds has observed, flint mines are composed of two distinct elements. The broad, circular shaft was essentially a large open pit, dug collectively by a group of people, some levering out the chalk with antler-picks, others dragging the spoil to the surface and dumping it. The galleries that radiated out from the base of this pit, and from which the flint was removed, were so narrow as to only admit one person at a time. So much was this the case that some would have been too tight for a male adult to enter. In this sense, the space of the mine embodied the relationship between the labour of individual people (of diverse ages and genders) and that of the community, while at the same time possibly serving to ‘map out’ social distinctions. Different stages in the production process were spatially segregated, with blocks of flint being removed from the galleries and the base of the shaft, but being flaked into preforms or roughouts on the surface surrounding the pit. The final grinding and polishing of axes appears to have taken place elsewhere, and this reflects the position of the mines in the wider landscape.

Anne Teather has pointed out that flint mines created their own kind of inaccessibility beyond the physical: descent into the earth, like climbing up to remote rock locations, took the ‘extractors’ into realms that were both physically removed and dangerous. She has, moreover, noted that the range of depositional practices within the shafts and galleries are in some ways comparable to the complexities of deposition in causewayed enclosures, and similarly the mining shafts and galleries are wholly constructed spaces: they were in effect monuments in their own right. In view of their relative remoteness from the world of everyday activity, the manifest dangers of their excavation and the extraction of flint nodules, and their very character as humanly created places, it is hardly surprising that among the debris are highly structured deposits, scratched markings on walls, and a considerable number of ‘decorated’ detached blocks and both shaped and scored chalk items. It is difficult to avoid the impression that many such items and markings were left as offerings to unseen, fundamental forces, or were apotropaic (that is, having the power to avert evil influences) in character. As such, the flint mines served both as source and as shrine.

The Sussex flint mines would have been conspicuous features in the landscape, surrounded as they would have been by glistening white spoil tips and replete with carpets of flaking debris glinting in the play of sunlight and shadow. While these mining sites were often positioned on false crests that would have been visible from the coastal plain and the sea beyond, they may have been less obvious from further inland. There is only modest evidence for occupation in the immediate environs of the mines, and it is probable that they were relatively distant from areas of settlement, being visited and worked in the summer months. These were special places, set apart from much of the rest of daily life, where special objects were brought into being in a new and different way. As distinct from other forms of lithic procurement, this involved entering into the earth, a growing preoccupation as the Neolithic progressed. While the various depositional practices that we have previously discussed involved placing things into the ground, Alasdair Whittle has argued that flint axes might have been construed as ‘gifts from the earth’, reiterating the possibility that the land itself was seen as a living entity with which people enjoyed reciprocal relations. In similar vein, Miles Russell has suggested that entering a flint mine would have constituted a rite of passage, encountering a place of metaphysical as well as physical peril. Visitors would return to their communities in a changed state, so that the mines represented places of transformation in which the identities of both axes and people were created.

The character of flint mines as special, and perhaps marginal, places is reflected in the materials that were deposited in them. There are several burials in the Sussex mines, and interestingly some of them are of women, which contradicts any simple assumption that the extraction of flint would have been an exclusively male activity. The use of mines for burial implies that their use may have been monopolized by particular kin-groups, who asserted their proprietorship in this way. Cattle remains are also present, such as the two ox skulls in Tindall’s pit at Cissbury. Upon their abandonment, the mines were often backfilled, and this was sometimes undertaken with some formality. There are often layers of flakes or nodules in the backfill, as if it mattered that they were returned to a former, inviolate state. Indeed, in some cases the deposits that had been quarried from the shaft had been returned in reverse order, replicating an envisaged former order.

In the Late Neolithic, the pattern of special rather than everyday objects being produced at the flint mines in Sussex and Wiltshire was continued and developed at Grimes Graves near Thetford in Norfolk (Fig. 4.1).

This was the largest flint mine complex in Britain, with four or five hundred shafts, although only a fraction of these would ever have been open at a given time. Only small numbers of flint axes were produced at Grimes Graves, and the emphasis was now firmly placed upon the production of more specialized items: discoidal and plano-convex knives, oblique arrowheads, and fine flint daggers. Like the axes from the Sussex mines, the artefacts from Grimes Graves are likely to have been made for exchange, sometimes over considerable distances. Indeed, rather little of the flint extracted from the mines has been discovered in the immediate vicinity. It is perhaps significant that the working of these mines strongly coincided with the main period of production of Grooved Ware pottery, itself connected with the establishment of new networks of long-distance contact between several among the different regions in Britain. Grooved Ware is present at Grimes Graves, sometimes occurring in the context of carefully arranged deposits. At the base of one of the shafts, for example, sherds from internally decorated Grooved Ware bowls were found associated with an organic deposit placed on the surface of a platform of chalk blocks. As with the Sussex axes, it is to be presumed that the value of the knives, arrowheads, and daggers created at Grimes Graves derived from the location and manner of their manufacture. The evidence of rather formal and symbolically charged actions conducted in the mines indicates that here, too, this process was hedged about with ritual.

From feasting to deposition

In this chapter we are drawing attention to some of the practical engagements that made and remade Neolithic societies, many of them mediated through the manufacture, use, consumption, and discard of material things. Some of these activities were more or less constant throughout the period, while others were transformed in fundamental ways. One of the more conspicuous areas of human conduct throughout the Neolithic is the sharing of food amongst groups of people, which often amounted to feasting. Given the abundance of debris that has been identified from events of large-scale consumption, this was presumably to an extent performative, and involved the assembly of groups of people to share food in ways that maintained or enhanced social bonds, sometimes also developing patterns of prestige, obligation, and indebtedness in the process. This is achieved because the significance was in the killing, not just the eating, of animals (sometimes in a formalized manner, for instance as sacrifices) and the conspicuous consumption, in which much of the food provided might be deliberately wasted. Attending a feast engages people through the sensory experience of taste and satiated hunger, but also through witnessing the spectacle or the formalities involved, and affirming the social relationships that are reinforced in the process. Archaeology has sometimes tended to concentrate on the most distinct and spectacular forms of feasting, which can readily be identified through their material correlates. But in reality there is a continuum between the shared domestic meal and the sumptuous feast that seals an alliance between large social groups, or celebrates an important birth, marriage, or funeral. Moreover, the latter may acquire its efficacy by being understood as a more elaborate version of the former. That is, participants may come to feel a sense of mutual attachment similar to that experienced by immediate kinsfolk.

The scale and context of feasting activities in Neolithic Britain seem to have varied considerably. Runnymede Bridge, in Surrey, a site with extensive recurrent settlement during the middle of the fourth millennium bce, produced an assemblage of animal bones that indicated that joints of beef had been roasted over open fires, but that the bones and scraps of meat had subsequently been boiled in pottery vessels for soups or stews. Such was the quantity of meat involved that, in the absence of salting, storage, or elaborate distribution mechanisms linking dispersed communities, any slaughter of cattle would only have taken place when an appreciable number of people had gathered together. An adult cow produces in the order of 300 kg of meat and offal. The slaughter of numbers of these animals attested from ethnography implies communal meals consumed by at least dozens and possibly hundreds of people, with more informal consumption taking place on subsequent days. Recent analysis of animal remains from pits on the Rudston Wold in East Yorkshire indicates a similar pattern of feasting on a moderate scale, concentrated in the winter months, during the Late Neolithic.

However, a more variable pattern of consumption is represented elsewhere. For instance, at the large settlement that preceded the construction of the henge monument at Durrington Walls in Wiltshire (see Chapter 5), animal bones from house floors and from pits associated with the abandonment of buildings showed that within or around these buildings meals had been shared by relatively small groups of people. These meals had occurred throughout the year, and many of the bones came from mature pigs in their second year of life. In sharp contrast, the remains from two large middens seemed to have been derived from much larger feasts held at midwinter, at which younger pigs had been roasted. Lipid residues from the Grooved Ware pottery from these middens showed that most of the vessels concerned had contained pork fats, whereas pots found in the vicinity of the large southern timber circle had held mostly dairy fats. It is possible to conclude from this pronounced difference that a distinct group of people, gathered in a focal area of the site, may have consumed particular foodstuffs in a distinctive way. This could represent an example of what Michael Dietler has referred to as a ‘diacritical feast’, in which the specifics of who eats what, and sometimes how, can serve to acknowledge and enhance social differences.

Another example of feasting on a grand scale in a distinctive way, apparently involving yet more overt display, came from the Beaker-era Barrow 1 at Irthingborough in Northamptonshire. Here, the skulls of 185 cattle had been incorporated into the limestone cairn of the round mound. These were prime young animals that had been butchered and stripped of their flesh some time before deposition. The meat from at least thirty-five of these animals had been consumed in the immediate vicinity of the barrow, and it is estimated that this much beef would have been enough to feed roughly a thousand participants. It is therefore possible that the barrow deposit as a whole could represent the bringing together of the remains of several such feasts during extensive mortuary feasting rituals within this part of the Nene valley, culminating in the deposition event marking the ‘topping out’ of the barrow, in much the same way that many of today’s building completions are celebrated. This Irthingborough extravaganza may, of course, be atypical, but it does provide us with a glimpse of the potential extent of funerary events at the very end of the Neolithic period, marking the passing of particularly important individuals, or groups of such people. In the context of rather later pre-Classical Greek culture it would be possible to conceive of such an event as the aftermath of a serious martial encounter.

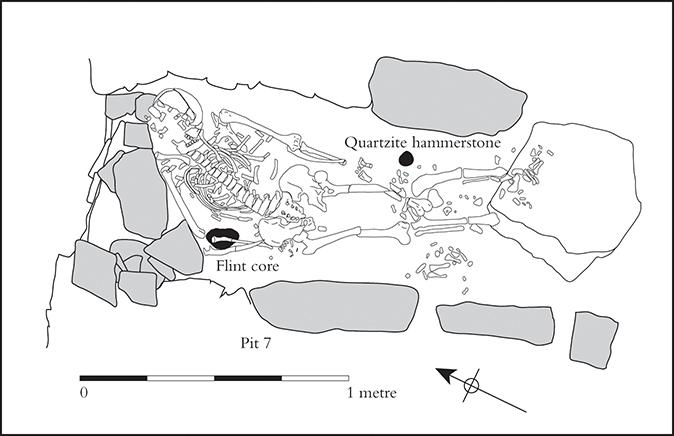

There is an obvious link here between events of consumption and episodes of deposition, in that one is often the outcome of the other. The deliberate placement of artefacts, human and animal remains, and other substances including charcoal and midden-material in pits, in ditches, and in the chambers of barrows was a pervasive theme throughout the Neolithic. While these materials are to some extent mundane, they may nonetheless have been understood as potent or polluting (or, paradoxically, both), owing to their status as the residues of either everyday, or more special, human activities. Hearth ash, for instance, is virtually ubiquitous in Neolithic pits, potentially having connoted both the role of the fireplace as the focus of the household and the importance of fire in the preparation (and transformation) of food. Although in later periods of prehistory pits were dug as storage facilities, particularly for grain, and only used as receptacles for rubbish when they were no longer needed for this primary purpose, Neolithic pits were dug deliberately to receive these kinds of specific deposit. Their edges are generally sharply defined, indicating that at the point of refilling they were freshly dug and therefore not yet weathered. They rarely give any impression of having been used for any other activity. Furthermore, they are usually of neither an appropriate size nor shape for use as a cereal store.

There are two aspects that differentiate the contents of these pits—selectivity and arrangement—and both contribute to an impression of increasing formality, and a more rigidly structured series of acts as time progressed. Generally speaking, pits from the earlier part of the Neolithic period contain deposited material that gives the impression of having been scooped up from a midden or occupation surface, and any objects contained within the soil and ash are disordered and confused. An exception is the site of Roughridge Hill in north Wiltshire, where groups of items including pottery fragments, stone tools, bone pins, and animal bones had been placed around the pit edges. But the more common pattern is described by Amelia Pannett amongst a series of pit groups in Carmarthenshire, the earliest of which contain jumbled masses of material that might easily have derived from domestic activity, while later Neolithic examples included fragments of human bone and stone tools that had deliberately been broken. In Ireland, Jessica Smyth has described a similar situation, with unusual artefacts and concentrations of human bone being progressively added to a standard pit assemblage of charcoal, flint, pottery, and burnt hazelnut shells from the later part of the fourth millennium bce. On the Isle of Man, Timothy Darvill has identified a variant of this pattern, where the random scatters of Early Neolithic pits were replaced by more spatially structured arrangements which sometimes included Ronaldsway jars buried up to their necks, and human remains.

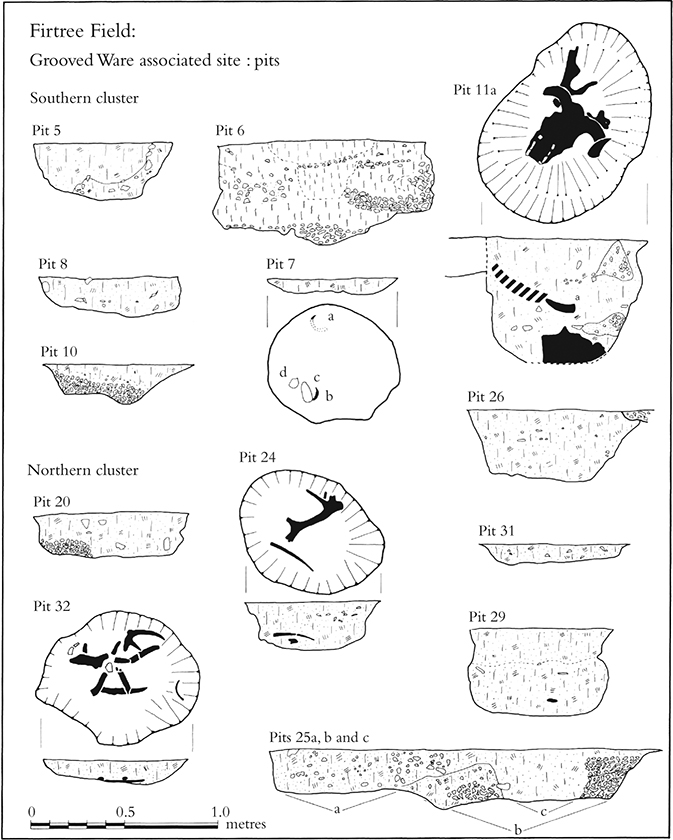

This tendency toward greater structure and complexity in pit contents reached a peak with the appearance of Grooved Ware pottery. Joshua Pollard has described as ‘sculpted’ the bowl-like forms of Grooved Ware pits, which sometimes contain sherds of pottery that have been arranged to form distinct surfaces within the pit fill. They can also often contain objects that are distinctive, or have been conspicuously placed, such as the group of flint scrapers that had been piled one on top of another at Over Site 3 in Cambridgeshire. Another good example is the large circular slate plaque engraved with a chequerboard pattern recovered from a Grooved Ware pit inside a causewayed enclosure of earlier date near Truro in Cornwall. At Firtree Field on Down Farm in north Dorset, sixteen Late Neolithic pits containing Grooved Ware were found in two distinct clusters (Fig. 4.2).

The northern group was associated with a series of three-metre diameter arcs of stake-holes, probably indicating a former occupation site. Yet the southern group was positioned closer to the nearby Dorset Cursus, and contained the richest and most complex material. The kinds of items placed in these pits included boars’ tusks, an ox skull, red deer antlers, and a slab of pottery laid decorated side up. These materials were placed on the bases of the pits, and were evidently intended to be viewed, at least for a short period of time. Such arrangements may have been intended to be witnessed openly, by an entire community, or they could have been committed to memory by a restricted group officiating at what may have amounted to a form of ceremony. Equally, they could have been undertaken as part of an ongoing dialogue with the unseen: spirits, natural forces, ‘gods’, or ancestors. It is important to recognize that any one of these three possibilities could have produced the same outcome, and that some acts of dedication would have combined elements of any of the three. While the implication of this is that pit deposition might sometimes have constituted a kind of ‘ritual’, we would emphasize that this does not mean that it was set apart from everyday life. If the materials employed were often the remnants of unexceptional activities, their deposition might constitute a more reflective moment woven into the commonplace, as when people of faith today either cross themselves when passing a wayside shrine, or unroll a prayer mat in their place of work, or offer a benediction before a meal.

Deposits in and near monuments, often in ditches or post-holes, should not be understood as categorically different from those in pits, although they may have served to embed the potency of materials and substances in specific places. From the later fourth millennium onwards, it is significant that deposits were often made after structures of one kind or another had gone out of use. Grooved Ware pits were sometimes dug close to the remains of the timber halls of the earliest Neolithic, including White Horse Stone and Parc Bryn Cegin, as well as the rather later unroofed timber structure at Littleour in Perthshire, whose form arguably mimics that of a hall. At Durrington Walls in Wiltshire, more pits containing Grooved Ware were cut into the floors of the Late Neolithic houses when they went out of use, as part of the abandonment process. This echoes the way that pits were dug during or after episodes of habitation on more ephemeral occupation sites throughout the Neolithic. Similarly, pits filled with Grooved Ware and animal bones were dug into the tops of the rotted-out uprights of the great southern timber circle at Durrington. This could be compared with the elaborate deposits placed into the ragged craters left behind after the withdrawal of massive posts from the Dunragit palisaded enclosure in Galloway. This was part of the process of decommissioning, but it was also a means of committing the past to memory, and perhaps a way of reinforcing the connection between monuments and houses, for both were treated in the same way at the end of their use-life. There is also reason to suspect that some of the large monuments of the third millennium bce drew their power from being understood as the collective ‘houses’ of large groups of people, as we will see in Chapter 5.

However, just as substances and artefacts were placed in pits that served to mark or secure the memory of places where human activity had occurred, sometimes pit deposits seem to have anticipated or conditioned the later use of a location. The large Early Neolithic pit at Coneybury, which we have already discussed, was first discovered because it lay close to the Coneybury Hill henge monument. Other monuments that had been preceded by pits include the henges at Balfarg in Fife and the Pict’s Knowe near Dumfries, the Middle Neolithic enclosure of Flagstones House in Dorset, the stone circles of Machrie Moor on Arran, and the Holywood South cursus, also near Dumfries. Although pits can hardly have left a substantial physical trace in the landscape, it seems highly likely that the accumulated histories of particular localities were intimately known, and remembered for very long periods. Indeed, this knowledge of places, and of who had done what and where, is likely to have been fundamental to how Neolithic people became familiar with the land and found their way around. This might be seen as a means of anchoring people into a sense of their rights to the inhabitation and use of particular places, particularly where occupation was sporadic and episodic rather than continuous.

Mesolithic people certainly showed an interest in the world below the earth’s surface, making use of caves and sometimes digging pits. Indeed, developer-funded archaeology in eastern Scotland has recently revealed that Mesolithic pits may be much more common than has often been assumed, especially in the later fifth millennium bce. A significant proportion of these pits contain no artefacts, and their date is only revealed if a radiocarbon determination is undertaken. So pit digging is another practice that spans the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition, and there are sites such as Girvan Warehouse 37, where Mesolithic pits were re-dug in the Early Neolithic and sherds of carinated bowl pottery introduced. However, having said that, it has become clear from the by now numerous archaeological excavations of often quite considerable tracts of landscape that from the start of the Neolithic the proliferation of crafted objects and built structures was matched by an exponential growth of interventions into the earth. Pits that received deposits were only one aspect of this development, alongside the ditches of enclosures and long barrows, the post-holes of timber structures of various kinds, flint-mine shafts, and the insertion of cultural materials into the openings left by the root-boles of toppled trees and natural shafts such as those at Fir Tree Field in Dorset, Cannon Hill in Berkshire, and Eaton Heath in Norfolk. Similarly, Jessica Smyth has drawn attention to the deposition of items including axes and arrowheads into the beam-slots of Early Neolithic buildings in Ireland. In this way, while Neolithic people extracted materials from the earth (clay for potting, flint for knapping, daub for building, quarried stones for structures or to stand upright, chalk used for carved objects and for the fabric of monuments), they also replaced them with other things. In a world in which substances from, and features of, the landscape may have been understood as being animate and imbued with force and potential, it is conceivable that these actions were seen in terms of reciprocity with the earth itself, as a means of making reparation for opening up wounds in the land, as we have already argued in the case of flint mines.

Placement of artefacts in a pit generally represented the end of their use-life, but other forms of deposition might have provided a more temporary resting place. The gathering together of a variety of different organic and inorganic materials in mounds or spreads of ‘rubbish’ as middens can be identified as a means of storing value, potency, and potential, sometimes for later retrieval. In this respect, such middening represents a variation on the theme of accumulation that more widely characterizes the Neolithic, and is also seen in the amassing of herds of cattle, or the gathering up of human remains and placing them in the chambers of long mounds. Flint cores, axe fragments, pottery vessels and animal bones were placed in middens, from where they might potentially be recovered at a later time. Middens represented an important element of British landscapes from the start of the Neolithic, although it is arguable that they shared some features with the shell-middens of the Mesolithic, which we have already mentioned. In the area excavated in advance of the creation of Eton Rowing Course by the River Thames near Windsor in Berkshire, a series of large middens built up in existing hollows in the ground from the thirty-ninth century bce. While these deposits were not accompanied by significant structural evidence, they appear to have accumulated as a consequence of cyclical or recurrent occupation beside the river. Here the middens themselves may have served as enduring markers of commitment to a particular location.

Throughout the period, objects occur in Neolithic contexts that seem to have been conserved for appreciable periods before their final deposition. In Chapter 6 we shall discuss the cattle and deer bones from the ditch of Stonehenge, which were already more than a century old when they were deposited. In the Firtree Field pits mentioned above, three pieces of Peterborough Ware were found amongst an assemblage that was otherwise dominated by Grooved Ware. All are recognizable rim sherds, parts of vessels that unambiguously represent a different ceramic tradition. Although it is probable that the Grooved Ware and Peterborough Ware traditions overlapped chronologically to a limited extent, the most likely explanation for the co-occurrence of such contrasting styles of pottery is that the Peterborough Ware fragments were already ancient, and had been retrieved from a midden with the intention of redepositing them. A similar phenomenon was recognized at Horton in Berkshire, where organic residues on a large fragment from a Peterborough bowl produced a radiocarbon date centuries earlier than charcoal from the Grooved Ware pit from which it was recovered. As we shall see in Chapter 6, this particular practice was by no means an isolated one.

Ann Woodward has acutely observed that some of the graves of the Beaker period contained fragments from pots that were apparently much older than the principal vessel that accompanied the burial. Her view is that special pots, particularly those that had been used in feasts and other important events, or that had belonged to significant persons, might have been secured in middens for generations before being used as funerary goods, thus bringing with them a tangible trace of collective history. Other objects, too, seem to have been retained for long periods and deployed in mortuary contexts during the final stages of the Neolithic. At Raunds Barrow 1 in Northamptonshire a pig tusk placed in the primary grave was centuries older than the burial, while an archer’s wrist-guard found nearby had been refashioned from a stone axe of Cumbrian origin, which may have been as much as a millennium old when desposited. We will have more to say about these practices of ‘curation’ and their relationship to history and memory in Chapter 6.

Dwelling

At several points throughout this book we have referred to the burying of various items in pits, more and less formally. Among reasonable questions to ask are: what relationship did pits have to the places where people were living? And, if people occupied living structures other than the timber halls identified at the beginning of the period and the cellular houses known at the end, what form did such buildings take? One potential difficulty that is raised by a focus on practices and activities in the past is that it can lead us to think of human life as composed of a series of bursts of action, during which the archaeological evidence that survives into the present is created. In between, past people fade from our concern somewhat, apparently no longer doing anything significant. One answer to this is to complement our interest in cultural practices with the issue of dwelling or inhabitation. By this we mean that humans are constantly involved with their world, attentive to what is going on, responding as required, in a rolling dialogue with other people, animals, and things. Their plans and projects are always maturing and being carried forward, at once informed by their past and projected into the future. So rather than thinking about separate episodes of doing being scattered about the landscape, we should consider instead the way that the course of life draws these happenings together in the continuous flow of human conduct.

How then might this perspective affect the way that we understand pits, middens, and buildings? To begin with, there are many deposits that derive from the debris of living—in particular from the preparation and consumption of food, and from the working of various materials in the course of making, using, and repairing things. We know, of course, that the sites of some long barrows were initially marked by the formation of middens, and how these middens comprised mounds or spreads of such debris. Middens have also been found on the margins of stream-channels, where they could, as at Runnymede Bridge by the Thames in Surrey and Eton Rowing Lake near Windsor in Berkshire, have been very extensive and in use repeatedly. There may have been to some degree, and at certain times and places, an overlap between the occurrence of middens and pits, and some but by no means all pits were places where ‘midden-debris’ could be disposed of (instead of being used to help form middens). The messiness involved in the placing of material in these various ways should not surprise us; nor should it be expected that Neolithic places were tidy in any modern sense (although the interior of some structures was clearly regularly swept clean). Two things that we do need to try to explain, however, are why the contents of pits differed in any one location, and to some extent between them; and what the relationship was between middens, pits, and ‘dwellings’.

Some recent investigations have gone a long way in helping us to address these issues. As was discussed in Chapter 3, at Kingsmead Quarry, Horton in Berkshire, a number of timber halls or houses have been identified, dating to the thirty-eighth century bce (Fig. 4.3).

Some generations later, a cluster of pits was created close by, whose rectilinear arrangement seemed to echo that of one of the buildings. The pits are suggestive of temporary occupation, and at Wellington Quarry in Herefordshire it has been suggested that the activities represented in pit contents are indicative of a stay of two or three months at a time. But neither houses nor pit locations need have been inhabited year-round, although both might have fulfilled the role of tethering and channelling human lives. At Kilverstone in Norfolk, meticulous analysis by Duncan Garrow, Emma Beadsmoore, and Mark Knight has illuminated the formation of the contents of 226 Earlier Neolithic pits, which formed a series of discrete clusters (Fig. 4.4). Both burned and unburned sherds of pottery that could nonetheless be refitted with each other were found to have been buried in different pits. The fact that they had also been affected by differential degrees of abrasion indicates that they had been subject to a range of different processes between breakage and deposition. Along with food debris and flintworking residues, they formed part of the gathered-up mess from what was a perhaps a seasonal settlement. This gradual accumulation of residues was punctuated by the digging and filling of more pits. Although the refitting exercise conducted by the archaeologists showed that there was material from the same items located in different pits within the same groups, the contents of the groups of pits overall were found to have been mutually exclusive. In turn this suggests that each set of pits related to the activities of a distinct group of people, possibly those who occupied the ephemeral structures implied by the layout of each cluster, just as at Horton. The overwhelming impression was of repeated returns to a particular location, over a period of possibly fifty to a hundred years, by a community composed of a number of distinct segments, or households.

In a subsequent analysis of assemblages from the Etton causewayed enclosure in Cambridgeshire (already introduced in Chapter 3), Garrow, Beadsmoore, and Knight went on to demonstrate that the deposition of material in the ditch segments was organized in an entirely different way from that in the Kilverstone pits. While fragments of pottery and flint exhibited conjoins that linked only pits within a given cluster at Kilverstone, the refits at Etton spread across the entire enclosure. It follows that the spatial character of activity was quite different in the two sites, and to a degree (by extension) the two kinds of site. Furthermore, while deposition at Kilverstone was more intensive, taking place energetically over a short span of time, that at Etton may have been more sporadic in nature, with perhaps shorter episodes of occupation dispersed over a much longer period of time. While Kilverstone produced greater quantities of flint, Etton revealed more pottery, perhaps demonstrating a greater preoccupation with consumption at the enclosure, rather than the manufacture and maintenance of tools. These contrasts are highly instructive, but it is important to remember that both sites represent merely facets of the way in which a landscape as a whole was inhabited by Neolithic communities.

Herding and hunting

The advent of the Neolithic changed the relationship between people and animals. While Mesolithic people had no doubt often decisive encounters with deer, aurochs, pig, and other species in the course of hunting and tracking, these creatures were unlikely to have been viewed as ‘property’, even when they were killed and their meat distributed within a community. Domestication is a biological process in which human beings come to influence the conditions under which animals reproduce. But equally importantly, it is a social process in which the relationships between people and the creatures they raise become more continuous and more thoroughly interwoven, and the notion of investment in stock management inevitably leads to the development of proprietary attitudes. Such cohabitation also brought about a transformation in two other dimensions of food acquisition. On the one hand, the ongoing practices of hunting during the Neolithic were likely to have become focused in a different way as a supplement to, rather than a mainstay of, subsistence. While hunting would always have been to some extent a recreational and a ‘testing’ activity for its participants, the group-composition of game animals taken to supplement the diet or provide specialized foods for more limited consumption would have differed subtly from previously, and may have been seen to pertain to ‘ancestral’ relations and practices. On the other hand, herders have to feed and water their animals, move them between pastures, control their breeding, wean them, milk them, and keep them safe from pests and predators. All this requires people to accommodate the rhythm and tempo of their lives to those of their livestock much more closely than following the seasonal habits and movements of game, or the appearance of naturally growing forage foods. The attachment of a human community to a herd of animals that represents a collective investment tends to have a more strongly routinizing effect, both through the coordination of everyday practice demanded, and by limiting social fission or fragmentation. In Chapter 6 we will discuss further the particular connection between cattle herds and human kinship, and the ways in which history and descent were embodied in livestock.

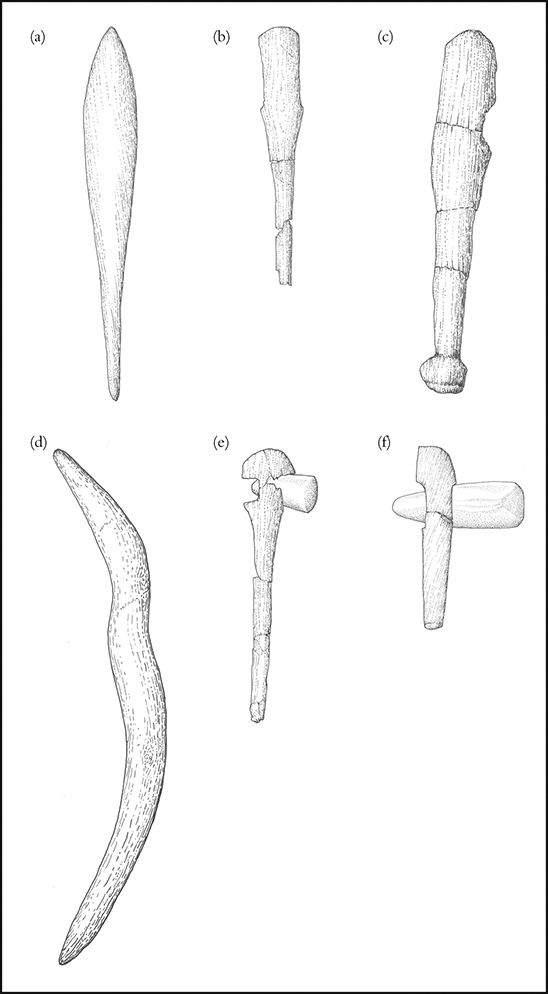

The groups of animal bones found during archaeological excavations of Neolithic sites in Britain were dominated throughout the period by the bones of domesticated species. However, one recurrent exception to this is the very large numbers of red deer antlers found in flint mines, and in the ditches and post-holes of long barrows, causewayed enclosures, cursus monuments, and henges. These antlers, with all but the brow tine removed, were used as picks for levering chalk and stone from the ground. In the 1967 excavations at the great henge of Durrington Walls in Wiltshire, a group of fifty-seven such antler-picks was found dumped on the base of the ditch terminal immediately to the south of the southern timber circle. A further staggering 354 picks were recovered from the post-holes of the circle itself, prompting the suggestion that they had been deliberately abandoned because their use elsewhere would have been considered inappropriate. The great majority of these antlers had been shed, rather than taken from deer that had been slain, but the abundance of antlers at these sites provides an interesting contrast with the relative paucity of deer bones from most Neolithic contexts, and particularly those identified with domestic occupation.

One exception is the large pit known as the ‘Anomaly’ excavated on Coneybury Hill, south-east of Stonehenge, dated to the later thirty-eighth century bce, and already discussed in Chapter 2. This pit contained the remains of ten bovines, two red deer, one pig, and several roe deer, which had all presumably been butchered nearby. While the roe deer had apparently been eaten on site, the meat of the cattle and red deer had been taken away for consumption elsewhere. The Coneybury Anomaly assemblage suggests an important social episode such as a feast, but why had so much food been removed? It may be that part of the answer lies in a degree of cultural ambivalence over the killing and butchering of deer. The event at Coneybury had clearly taken place at a remove from some other location, to which the choicest of the meat had been taken. This same ambivalence has been identified by Niall Sharples at a number of sites in Late Neolithic Orkney, at which red deer had been killed or consumed outwith settlements, where deer bones are rarely found at all. At the Point of Buckquoy, an isolated midden was found, containing numerous bones of red deer. At the Bay of Skaill, a butchery site was excavated, with the remains of four deer and a number of flint knives that had been used to remove the meat from the carcasses. Finally, at the settlement of the Links of Noltland, fifteen red deer had been slaughtered in a single episode and dumped in a heap, before being left to rot. The animals were deposited beside a wall retaining a midden deposit, distinct from the settlement area. They were predominantly females, and all but one had been laid on their left-hand sides.

Seemingly, red deer (and perhaps wild animals in general) were routinely consumed by British Neolithic people, but dealings with them were kept separate from dwelling areas. Their bones may, therefore, be underrepresented at some occupation sites. Two possible interpretations suggest themselves. First, although it is very unlikely that the modern distinction between ‘culture’ and ‘nature’ was consciously applied by people in the Neolithic period, it is possible that animals that had been fully incorporated into human society could be brought near to dwellings, but that creatures that were encountered only intermittently, and that were connected with the forest and the wild, had to be kept at arm’s length. Alternatively, it may be that deer in particular retained an association with an increasingly mythic pre-Neolithic past. As a particularly important animal that had been hunted during the Mesolithic period, deer might have been displaced as a primary food source while at the same time their meat became more highly prized. As such, this meat may have been consumed in more particularly ritualized and exclusive, even perhaps semi-clandestine, circumstances, following which their antlers were collected and used for digging, but abandoned in their place of use. Equally, animals that rarely came together in groups, and that inhabited the forest or other remote places, such as the aurochs (or wild cattle), may have been hunted under special circumstances with attendant inhibitions. Their bones occur in a trophy-like manner in Neolithic sites, mostly as individual finds and apparently not as the debris from feasting.

Harm

Vicki Cummings and Oliver Harris have proposed recently that following the transition from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic, the practice of hunting continued, but it came to be focused on people as well as animals. While the burial record for the Mesolithic is such as to inhibit comparisons, there is little doubt that Neolithic societies in both Britain and Europe engaged in some level of violence. The earliest Neolithic societies of central Europe, known collectively as the Linearbandkeramik, are associated with a number of massacre sites. These include the Talheim ‘death pit’ near Heilbronn in Germany, containing what may potentially have been the entire population of a small settlement, many of whom had been dispatched by blows to the head from stone axes. While the Mesolithic should certainly not be construed as a period of idyllic peace, it does seem that one of the innovations of the Neolithic was likely to have been an increase in interpersonal conflict. Rick Schulting and Michael Wysocki have described thirty-one instances of healed and unhealed cranial trauma from a sample of 350 skulls from funerary monuments in Britain. This would not in itself represent a high level of injuries, but when post-cranial and soft-tissue wounds, and in particular projectile impacts, are added, it is enough to suggest that violence was a significant factor in Neolithic life in Britain. Other indications of aggression include the evidence for attack at the enclosure sites of Crickley Hill in Gloucestershire and Hambledon Hill in Dorset, in the form of extensive burning, dense concentration of flint arrowheads, and in the latter case a body in the ditch with an arrowhead in its chest cavity. Similar indications of conflict are evident at the Cornish tor enclosures (rocky hilltops enhanced with walls made from piled stones) of Carn Brea and Helman Tor, where large numbers of leaf-shaped flint arrowheads have been found, that appear to have been shot towards and into entranceways, as if the latter places had been under ferocious attack.

Moderate but continuous levels of violence, or endemic conflict, are often a feature of pre-state societies. For social anthropologists, these can be understood as cases of ‘negative reciprocity’, the darker counterpart of exchange, feasting, and gift-giving. Whom one fights against, and whom one fights alongside, can have considerable consequences for the reinforcement or dissolution of social relationships. Indeed, the main purpose of creating alliances between communities may be to facilitate aggression against other groups. Joining a war band or a raiding party is often an obligation imposed on those who find themselves in a position of indebtedness, while deaths that happen during conflict may need to be compensated by the payment of blood-price. Yet while these structural aspects of warfare are fundamental, it is also important to point out that violence is both an embodied activity and, to some extent, a performance. In many pre-industrial societies fighting provides a context for display, in which reputations are built and maturity or adulthood is achieved. Some Neolithic artefacts such as bows and arrows, hafted flint and stone axes, and, in the Beaker phase, flint daggers had the capacity to link aggression with personal identity. Not all such items had to have been used in anger, but it is nonetheless probable that the achievement of personal repute in the Neolithic was often connected with martial prowess. The evidence for archery in particular provides some important clues regarding the changing character of violence during the period. In the Mesolithic, arrows were made using multiple microliths inserted into a wooden shaft and held in place with resin and twine. One small flint might form a point, but numerous others would make up rows of fearsome-looking barbs. In the woodlands of the mature postglacial period, such weapons were well suited to hunting deer and pigs. In a context where such animals might emerge from the undergrowth and be visible only momentarily, a well-aimed arrow might not kill outright, but would lodge in the creature’s flesh, causing an aggravated wound that would drip a trail of blood that could be followed as it tired. The leaf-shaped arrowheads of the Early Neolithic, however, were quite different in character, comprising as they did a single blade-like point, best suited to piercing. These arrows were more readily used against human beings, in the changed circumstances of the fourth millennium. With the formation of more closely bounded communities that maintained more exclusive control over resources, conflict between social groups might be expected to have increased. Most pertinently, cattle now constituted a form of mobile wealth that could increase a person’s social standing in manifold ways. While the causes and forms of conflict during this period may have been numerous, we would reiterate that cattle-raiding is likely to have featured prominently amongst them.

By the later part of the millennium, the character of arrowheads had changed yet again, first to a preponderance of chisel-shaped (so-called petit tranchet-derivative) forms, and then to lopsided oblique types, often with a hollow (concave-curving) base and sometimes with delicate ripple flaking on the dorsal surface. These arrows would have been less aerodynamically efficient than the leaf-shaped ones, and in the case of the oblique styles, less suited to killing an opponent outright. However, the deployment of such projectiles in close combat would have had the potential to cause spectacular and bloody wounds, severing ankle tendons (for example) and disabling opponents, causing them to retire from the immediate engagement. Descriptions of historically attested and comparatively recent warfare in various parts of the world suggest that in some cases it is preferable to incapacitate than to kill an opponent, where the latter might result in reprisals and revenge killings. One possibility, therefore, as pointed out by Edmonds and Thomas as long ago as 1984, is that during the Middle and Late Neolithic the nature of conflict became more ritualized and constrained by convention, and more concerned with performance and display than with the wholesale slaughter of enemies. Another indication that archery was not entirely utilitarian in character during the Late Neolithic is provided by the animal bone assemblage from Durrington Walls. Here, many of the domestic pigs had been killed with arrows, rather than simply having been slaughtered by poleaxing or having had their throats cut. The implication is that pig-killing involved a degree of arranged spectacle, with animals perhaps having been allowed to run free within a reserved space before being shot, performatively, as a combination of sport and ceremonial, or as part of the initiation rites concerning the passage of young people into adulthood.

Communicating with pots?

One of the considerable ‘laboratory science’ advances that has had an immense impact on Neolithic studies in recent years has been in the study of residues that have long been noted adhering especially to the insides of pottery sherds. More than this, the fatty substances (known as lipids) that have been absorbed into the very fabric of such often open-pored vessels as a result of cooking, storage, or processing of food have left a chemical trace that can be identified by a variety of techniques. One such, involving compound-specific stable carbon isotope analysis, has enabled the identification of meat and dairy products (especially milk) from Neolithic sherds, such that the consumption of milk and secondary dairy products (such as butter, cheese, and ghee) is now well attested (with all its implications for the tolerance—or otherwise—of lactose among the relevant populations).

Yet while new possibilities are opening up for the scientific study of residues in Neolithic ceramics in Britain, the significance of their design and decoration continues to be a topic of some debate. In this respect the study of Neolithic pottery in Britain and Ireland contrasts a little with that on the continental mainland of Europe. In the Scandinavian Trechterbekercultuur (TRB), the central European Linearbandkeramik (LBK) or the west French Middle Neolithic, finely grained internal sequences of typological development have been gradually refined and employed as a proxy means of dating. The British material has largely proved resistant to such an approach, while British archaeologists have often shown greater enthusiasm for independent, scientific forms of dating than their Continental counterparts. Pottery was one of the most distinctive innovations of the Neolithic, and while Mesolithic communities in some parts of northern and eastern Europe made and used ceramics, this was not the case in Britain. Pottery was therefore a radically new container technology, which introduced new possibilities for mixing, cooking, storing, and serving food and drink: a new ‘culinary alchemy’, which would potentially have changed the experiences of eating and drinking by creating unfamiliar flavours. It is also a highly plastic medium that offers the opportunity to create a great diversity of material forms. Pottery vessels can vary in size and shape, in surface finish, and in decoration, while the technological choices involved in achieving these outcomes can be quite extensive. Pots can engage the onlooker visually, and they can also offer haptic experiences of surface texture, while their shapes and sizes oblige people to engage with them in specific ways. Some of the variation in ceramic form can be put down to practical requirements: to withstand thermal shock, to contain different quantities of different materials, to serve different numbers of people, or to stand on different surfaces. But to some extent, pots of quite varied appearance may be equally fit for purpose, and their distinctive character cannot be explained exclusively in functional terms. In particular, we need to ask why distinct ‘traditions’ of pottery developed and were maintained for long periods during the Neolithic, and why they sometimes came to be replaced by others, occasionally within quite short periods of time. When the potential for creating distinctive pots is so great, why did people continue to replicate the same styles?

For the archaeologists of the interwar period this was a straightforward question to answer, since it was assumed that members of particular communities automatically inherited the ‘norms’ (or conventional ways of making and doing things) that had been developed by their group, and simply reproduced them without deliberation (see Chapter 6 for further discussion of this point). However, once we recognize that people make explicit choices in manufacturing and decorating objects, this view is undermined. Artisans always have the option of doing things differently, and one consequence of this is that their products can potentially carry some form of message, even if this is often quite mundane. This means that the different styles of pottery manufactured during the Neolithic did not simply reflect the ethnic or cultural identities of their makers: in some cases they may have conveyed information at a number of different levels, to different potential audiences. Some of these messages may have been quite vague and unspecific, as today when our choice of clothing or jewellery makes a statement about ourselves that may be only vaguely formulated. But in specific contexts, the use of particular pottery vessels may have carried connotations that were absolutely unambiguous.

This may be the case with the first pottery employed in Britain, the carinated bowl tradition, which was generally not decorated, but was nonetheless highly distinctive. It is notable that the very earliest of these assemblages, identified with the first Neolithic activity in the south and east of England, were relatively uniform in character, dominated by upright, bipartite vessels with simple rims, in fine, thin-walled fabrics with smooth surfaces. These were small groups of pots, often used for hospitality and the sharing of food at funerals, gatherings, and feasts. Their form had been selected from more extensive suites of vessel types in use in north-east France and the Low Countries (and slightly later from north-west France), and this suggests that the message they carried was not only one of adherence to a new set of social conventions, but also of connectedness to distant, prestigious, and powerful communities. Later forms of the carinated bowl tradition had surfaces that were ripple-burnished, and a few were sparingly decorated with incised lines. Subsequently, pots came to be used in more mundane activities, assemblages became larger, and their fabrics became coarser and thicker. A wider range of vessel forms was employed, generally drawn from Continental prototypes, but not always from the same sources. Furthermore, when incised, stabbed, and impressed decoration began to be more extensively applied to pottery from shortly before 3700 bce, the pattern of ‘mixing and matching’ that we have identified in other aspects of culture came into play: decorative motifs that would not have been out of place in northern Europe were applied to vessels of north-west French affinity, for instance. As discussed in Chapter 3, these Decorated Bowls formed distinctive regional groupings, but the boundaries between these were not strongly defined, while decoration was preferentially applied to particular forms of vessels (notably, but not exclusively, shouldered bowls) (Fig. 4.5). This may indicate that any message that the pots conveyed was related less to regional identity than to the activities or contexts in which pots were employed, or the specific people who made and used them.

The emergence of Peterborough Wares and Scottish Impressed Wares in the thirty-fourth century bce might be seen as a continuation and intensification of this Decorated Ware tradition, and the imperatives that gave rise to it. The shouldered bowl was transformed into something more densely sensual, with thick fabrics from which the large flint or quartz grits visibly protruded, and increasingly heavy, florid rims. A wider range of media was used to create multiple impressions over a greater area of the surface of the vessel, and these were more readily recognizable as the imprints of human extremities, bird bones, and natural fibres. If pottery can serve as a means of expression, the message was now more emphatic, and less easy to ignore (or perhaps it was merely identifiable at a greater distance). As we suggested in Chapter 3, this might mean that the interactions and transactions in which pottery was employed had become more vexed, and required greater protection or clarification. Yet unlike the Early Neolithic decorated pottery, the different substyles of Peterborough Ware were less obviously regional in character (although Yorkshire and Scottish variants were more geographically specific), and overlapped spatially. Ebbsfleet, Mortlake, and Fengate Wares were apparently in use alongside each other, and it may be that they were each favoured by different social groups within a locality, or were the prerogative of different groups of potters, or were reserved for specific segments within a community (based upon kin relations, age, gender, or status), or employed in different ranges of practices. The latter may be hinted at by the contextual variation in their occurrence.

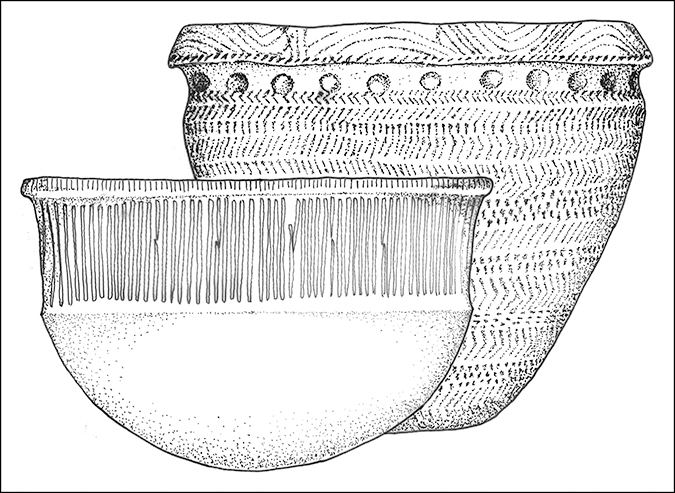

Grooved Ware, from the end of the fourth millennium bce onwards, marked both a change in the form of pottery from round-based bowls to tubs and buckets, and in the character of decoration (Fig. 4.6).

Unlike the earlier ceramic styles, Grooved Ware deployed motifs that had already enjoyed an existence in another context, in passage-tomb art. Grooved Ware thus served as a carrier for images that might also migrate onto carved chalk objects, stone plaques, carved stone balls, and maceheads. Not all of these necessarily occurred in the same places, or were used in the same practices, as Grooved Ware. Where Peterborough Ware bore the physical imprints of human bodies, animals, and plants, these were rarely shared with other media. The designs on Grooved Ware were generally more abstract, but also more obviously composed and geometric: chevrons, zigzags, lozenges, triangles, concentric circles, and spirals. They were truly symbolic, rather than indexical, so that if they represented anything in particular (or several things) they did so in an arbitrary and conventional way (although in some cases the skeuomorphic representation of basketry may have been intended: see ‘The art of transformation in skeuomorphic practices’, below). They established connections between separate contexts and locations, so that Grooved Ware constituted one element of a suite of material forms that introduced the same set of symbols or concepts into a range of different interactions. The same might be said for Beaker pottery, which was more obviously intrusive in the British context. Beakers were often densely decorated, but given the presently unresolved issue of who the users of Beakers might have been, it remains an open question whether this was principally ornamental or whether Beakers could be ‘read’ by some or all of those who encountered them.

Timberworld

The ‘Maerdy Oak’ post discussed in Chapter 2, and the pine posts mentioned there and elsewhere in this book, indicate clearly that Mesolithic people in Britain had the capacity to create substantial structures in timber, albeit that the larger posts were likely to have been free-standing and not always erected as part of structures. It is only in the Neolithic, however, that a more extensive suite of practices involving the use of wood in various ways becomes well attested. As is particularly evident in the case of the Sweet Track in the Somerset Levels, it is both the scale and the skill of such works, and their deployment from as early as the opening centuries of the fourth millennium, that impresses even the casual observer. Moreover, as will be noted in Chapter 6, the very acts of clearance in both the late Mesolithic and the earlier years (at least) of the Neolithic often involved the marking of the place formerly occupied by the boles of the removed trees with deposits either of mixed midden material or more carefully selected groups of objects.

While, therefore, wood from trees was probably never regarded simply as timber, it was nonetheless the case that, from an early stage and at various points throughout the Neolithic period, whole tree trunks were cut and inserted upright into the ground, often along with poles cut from branches or from coppice stems that were used to create smaller or ancillary structures. We know about such usages from the survival of the holes dug to receive these normally vertically set timbers, and from the rotted or burned posts that in many places have been found to have survived within them. We have noted already that many such timbers in the Early Neolithic were parts of structures such as rectangular houses and halls that were likely to have been roofed over, but that from even before the middle of the fourth millennium bce others were part of free-standing settings of posts. In Scotland, these latter comprised post-defined, parallel-sided monuments that approximated to what were later built in southern Britain as ditched cursus monuments, while throughout mainland Britain they occurred as retaining structures, façades, and forecourts for long barrows. In the period from the later years of the fourth millennium bce, timber settings of upright posts occurred as part of palisades defining oval areas sometimes enclosing many hectares, or as simple circles of such posts with or without accompanying enclosing ditches and banks. More rarely, they occurred as concentric circles of posts such as the Northern and Southern Circles at Durrington Walls, and the nearby Woodhenge in Wiltshire, or more recently established by geophysical survey among the stone circles at Stanton Drew on the edge of the Mendip Hills in Somerset (Fig. 4.7).

The discovery of timber monuments, not only as precursors of stone structures and in areas especially of northern and western Britain where stone was abundant, tends to counter the notion that timber was only used for building such structures where stone was unavailable. Indeed, current understanding of the ubiquity and diversity of timber-built structures across the whole span of the Neolithic demands more inclusive explanations for the frequency with which the mostly oak trees concerned were cut and removed for erection as upright elements of complex architectural arrangements. In a survey of the variety of these kinds of timber structures in Scotland, Kirsty Millican has recently proposed that there was a major shift in timber building at around 3300 bce, with the linear or rectilinear character of the Early Neolithic timber monuments replaced thereafter substantially by circular or curvilinear forms (though straight and rectilinear settings did sometimes continue to form elements of the later complexes concerned). This shift was reflected also in a change in the manner in which these sites were decommissioned. Before 3300 bce they were often burned down to bring about their termination, but afterwards this practice is much less common and the timbers of the structures appear to have been left to decay. The fact that this shift correlates with other changes in material culture and social practices at the time strengthens the impression that this was part of a wider reordering of cultural links.

The question remains as to why such structures with monumental timber elements were built in the first place. One idea that has been popular among archaeologists, such as Gordon Noble, working in northern Britain is that they represented a kind of domestication or absorption of the forest within the social world of humans. This view certainly has its attractions, particularly when considered in reference to the proximity of many such structures to areas of woodland, or even their creation within clearings. The cutting and raising of so much timber clearly involved transformations, both to the landscape (Dan Charman and Ben Gearey showed over twenty years ago, for example, that one whole flank of Rough Tor on Bodmin Moor was clear-felled in a single fourth-millennium episode) and in the process of converting trees to timber. Beyond this, however, the construction of these buildings and settings arguably harnessed the scale and density of living, growing trees into particular projects that ordered them within a very human appreciation of order, creating specific effects of perspective, movement, concealment, and auditory cues. As such, they represented a transformational choreography of woodland and a three-dimensional arena for the renegotiation of social relations.

Trails of the axes: from procurement to exchange

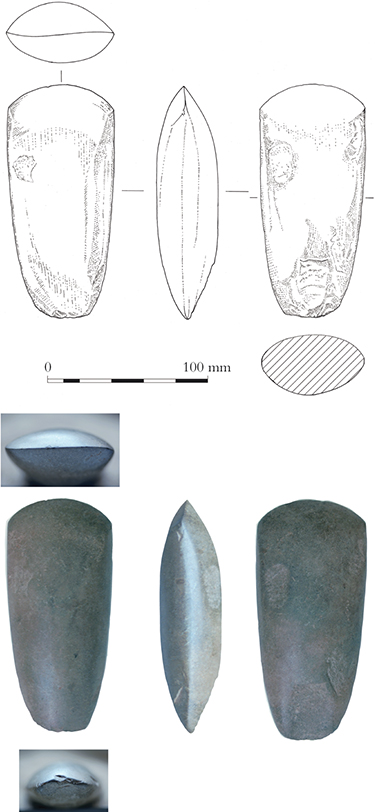

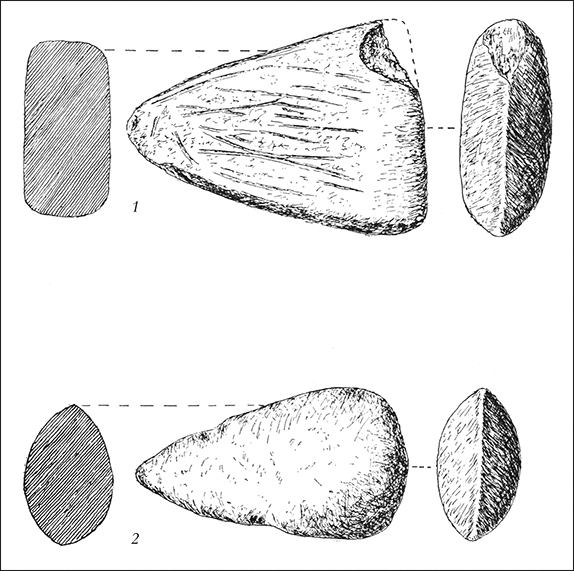

Stone axeheads are among the most ubiquitous of the objects that permeated the world of Neolithic Britain, and they have long fascinated archaeologists by their variability as well as their abundance (Fig. 4.8).