In Paris a fashion designer is sketching a new collection. At a convention in Las Vegas a buyer is looking among more than one thousand vendors to select dresses to sell in a boutique in Miami. In London a forecaster is analyzing data to predict the fashion trends three years from now. In Shanghai a merchandiser is preparing a report to propose the fashion direction for a popular chain of budget-priced retail stores throughout Asia. Each of these people is an expert in their field and each person will use a framework or principles of fashion to guide their decisions. The fashion designer will lower the hemline of dresses by two inches because she understands the directional nature of fashion. The buyer will scout for merchandise that is unique and exclusive because his customers desire to look different from other people. The forecaster will examine the social movements to make a prediction because she understands how society impacts trends. And, the merchandiser will flood the market with a few styles because he understands that if businesses offer a limited number of styles there is greater chance of them becoming a trend. Each of these people makes logical choices based on established principles and concepts of fashion.

The word theory is derived from the ancient Greek word theoria which meant “to look at or view.” Greek philosophers would “look at” a situation and try to find an explanation for it. In scientific terms today theories are a framework for thinking about, examining, or interpreting something. Consider the following definitions of theory:

•“A theory consists of a conceptual network of propositions that explain an observable phenomenon” (Lillethun, 2007, 77).

•“A systematic explanation for the observations that relate to a particular aspect of life” (Babbie, 2004, G11).

•“A set of interrelated constructions (variables), definitions, and propositions that presents a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relations among variables, with the purpose of explaining natural phenomena” (Kerlinger, 1979, p. 64).

•“An idea or set of ideas that is intended to explain facts or events; an idea that is suggested or presented as possibly true but that is not known or proven to be true” (Merriam-Webster, 2013a, n.p.).

•“A contemplative and rational type of abstract or generalized thinking or the results of such thinking” (Wikipedia, 2013, n.p.).

We can examine behaviors, actions, occurrences, works, and any other tangible or intangible phenomena. Theories are made of different parts that contribute to the total understanding. Part of the theory might be true while other parts might not have support, but it does not necessarily change the theory as a whole. “Like fashion itself, the theories that explain fashion movement are constantly revised and refined” (Brannon, 2005, p. 82). By analogy, a garment that is made up of a bodice, skirt, collar, sleeves, and cuffs is called a dress. However, if you take off the cuffs it is still called a dress, or if you add a pocket it is still a dress. Changing part of the whole does not invalidate the whole.

Theories are divided into three categories based on their scope of explanation: grand, middle-range, and substantive (Merriam, 1988). Grand theories are very broad, all-inclusive, universal and are useful for organizing other ideas; they offer general ideas, such as Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. Middle-range theories do not attempt to explain such overarching phenomenon as do grand theories but rather concentrate on limited phenomena; one could argue that the theory of collective behavior (i.e., that fashion trends are inspired by specific groups of people with unique aesthetic styles; further explained in Chapter 4) is a middle-range theory. And substantive theories offer ideas and reasons in a narrow setting, such as the reasons for Japanese immigrants to adopt westernized clothing in Honolulu, Hawai‘i in the 1920s.

Theories often come from concepts or laws. A concept is a general abstract idea; the idea of fashion—adoption of trends for a specific time period—is a concept. A law is a simple, basic description of phenomena that is undoubtedly true. The explanation of or why the phenomena occurs is a theory. A theory surmises or postulates why it happens. A theory is sometimes referred to as a theoretical framework. This is different from a conceptual framework, where the specific relationships between variables are detailed. A conceptual framework is nested within or based on the theoretical framework. For example, a theoretical framework might be that people tattoo their bodies to mark rites of passage. A conceptual framework will use this theory and examine specific variables—how do age, social rank, economics, and gender affect tattooing? Throughout this text you will find many examples of theoretical frameworks and conceptual frameworks.

Theories are developed from hypotheses. Hypotheses are educated guesses based on observation. Hypotheses can never be proven, only supported or rejected. When a hypothesis has been supported by numerous tests it becomes a theory. There is no guideline as to how many tests it takes to transform a hypothesis into a theory; rather, that decision is left up to the community studying it after they have determined they have exhausted all possible variations of the hypothesis.

Figure 1.1 Why is this man wearing a suit backwards? Is this a new aesthetic trend? Is this a protest? Is this a sign of postmodernity? Theory will help to answer questions like these and explain the reason for this peculiar display of dress. Iulian Valentin.

In a very general sense, we can say that “people wear clothing in civilized societies” is a law. The explanations why people wear clothing can constitute a theory. The ideas that test or support the theory are hypotheses that are accepted or rejected. You will see in the following example that with each level, the wording is more specific; it is moving from abstract to concrete.

Concept: Fashion—group adoption of a trend during a specific time period.

Law: People in civilized societies wear clothing.

Theory: People wear clothing due to climate conditions.

Hypothesis 1: As temperatures drop, people will wear more layers of clothing.

Hypothesis 2: As temperatures increase, people will wear fewer layers of clothing.

Hypothesis 3: The change in temperature will have no effect on the number of layers of clothing that people wear.

In order to test the hypothesis, you record temperatures in a given area and ask people how many layers of clothing they are wearing. When you analyze your data you find that when temperatures dropped, people added more layers of clothing, and conversely, when temperatures increased people wore fewer layers of clothing. Therefore, you accept hypotheses 1 and 2 but reject hypothesis 3. As a result you have found evidence that supports your theory that people wear clothing due to climate conditions. Other people may subsequently test the theory and find additional support, such as different types of clothes are worn during different climate conditions (e.g., rain, snow, drought) and therefore add to the body of knowledge about climate and clothing.

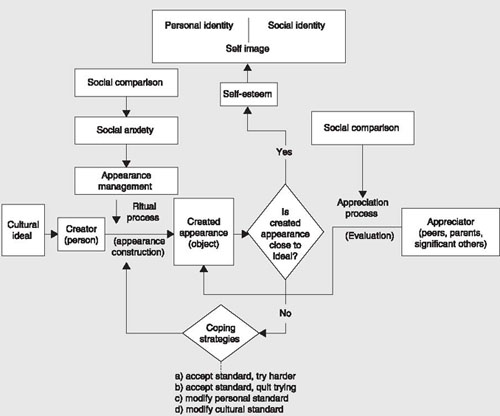

Models try to predict phenomena, based on theoretical framework, and are often represented as a diagram. A model can detail direction, interaction, and choices. Models can be based on theoretical or conceptual frameworks. The Rudd/Lennon Model of Body Aesthetics described in this chapter is an example of a model that summarizes the steps and decisions a person experiences when creating a personal aesthetic or “look.”

A taxonomy is a system of classification. In the Animal Kingdom, animals are divided into invertebrate and vertebrate, then further divided within those groups (vertebrate are further divided into fish, reptiles, amphibians, birds, mammals). Pets can be divided into categories (cats, dogs, birds) and then further with each group (short hair, long hair; breed; indoors, outdoors). Even your wardrobe can be divided using a taxonomy: casual, professional, special occasion, etc.; within those categories you can further divide them by color, price, and frequency of wearing. The purpose of a taxonomy is that it helps organize data based on similar qualities or characteristics to find commonalities, differences, and gaps. You may find that your wardrobe taxonomy informs you that you have an overabundance of special occasion clothes but not enough professional clothes. The Public, Private, and Secret Self is an example of a taxonomy that classifies clothing according to type of dress by level of self-expression and will be further detailed in Chapter 2.

Some explanations of phenomena are revised until an adequate theory is found. The theory of gravity was altered over centuries, with additions and revisions from Aristotle in 300 BC, Galileo Galilei during the European Renaissance, Sir Isaac Newton in the 17th century, and Albert Einstein in the last century.

Some theories compete with each other to explain the same phenomena. In trying to explain why people commit crime, a number of theories have emerged, including phrenology (the measurement of cranial features where dimensions indicate criminal capacity; since abandoned as a legitimate theory); biological causes (e.g., bad genes); social causes (e.g., poverty, education; group affiliation); psychological causes (e.g., childhood abuse); and environmental or ecological causes (e.g., isolated or darkened areas).

There are also competing theories regarding the original purposes of clothing. Historic evidence provides material products that can be interpreted through different lenses. Pierced marine snail shells 75,000 years old were found in a cave on Blombos, South Africa (d’Errico, Henshilwood, Vanhaeren, & Niekerk, 2005; Vanhaeren, d’Errico, van Niekerk, Henshilwood & Erasmus, 2013). Also found in the Blombos cave was ochre (Henshilwood, d’Errico, Yates, et al., 2002; Henshilwood, d’Errico, & Watts, 2009). The snail shells were pierced as if to tie on a string and ochre likely was used to decorate the body in pre-historic times (Schildkrout, 2001), therefore it is suggested that the items were used for personal adornment. In addition, a pendant in the shape of a horse carved from mammoth tusk was found in Germany and believed to be 32,000 years old.

Needles made of bone and ivory, 30,000 years old, were found in Russia (Hoffecker & Scott, 2002; Dorey, 2013), suggesting they were used to sew animal skins, animal fur, or fabrics together. Flax fibers found to be from 34,000 BC were found in an ancient cave in the Eurasian country of Georgia and surmised to be evidence of baskets and clothing (Kvavadze, Bar-Yosef, Belfer-Cohen, et al., 2009). Some of the oldest clothing items were found in contemporary Denmark and dated to the early Bronze Age (2900–2000 BC) (Boucher, 1987). These items were made of woven cloth and included sewn bodices, tunics, hats, belts, and a skirt.

While we know that clothing and personal adornment has existed for many millennia, the reason for their creation is debated. Many theories speculate about their original purpose(s). Greeks and Chinese believed the original function of clothing was to protect the body from weather and natural elements while other people (such as psychologists, religious scholars, etc.) argue that clothing developed to provide modesty, for magical purposes, or to be aesthetically pleasing (Boucher, 1987). Boucher writes:

[W]e may at least surmise that when the first men covered their bodies to protect themselves from the climate, they also associated their primitive garments with the idea of some magical identification in the same way that their belief in sympathetic magic spurred them to paint the walls of their caves with representations of successful hunting. After all, some primitive peoples who normally lived naked feel the need to clothe themselves on special occasions. (p. 9)

Boucher has noted the existence of five general categories of clothing: draped, slip-on, closed sewn, open sewn, and sheath. (In the modern period these types began to become interbred and new composite categories emerged.) Boucher, therefore, argues that while clothing can inspire fear or establish authority or project an image of power, because these types existed in different cultures and different discrete civilizations, something other than politics, race, or religion had to influence design—climate and geography. Thus, it is likely that the original purpose of clothing was for protection.

In 1991 a frozen man was found in the Ötztal Alps and nicknamed “Frozen Fritz.” Fritz dates from 3300 BC and the ice preserved portions of his clothing and body. At the time of his death he was wearing a coat, belt, belt pouch, leggings, and shoes made of leather, all of which had been sewn. Also found was a cloak constructed from grass woven together. In addition to his apparel, Fritz’s body was marked with tattoos that coincided with acupuncture points for ailments that Fritz experienced. It was therefore hypothesized that some of the tattoos were used for health purposes. Thus, while Fritz’s clothing may have been for climate purposes, his body adornment may have been for health.

The reasons for these changes in theory or alternative explanations are due to new knowledge and what the philosopher Thomas Kuhn (1970) called a paradigm shift. Kuhn defined paradigm as “universally recognized scientific achievements that, for a time, provide model problems and solutions for a community of practitioners” (p. 10). A paradigm, he argued, is a world view that colors ideas and thoughts. For example, the world view in Europe during the European Middle Ages was that the world was flat. Christopher Columbus’ journey helped to change that view and shift thinking towards a spherical earth although it was not readily accepted at first. Kuhn argued that paradigm shifts occur when anomalies cannot be explained by the existing paradigm and alternative theories and ideas are developed and debated, which creates a new paradigm. There are often disagreements between followers of the former and the new paradigm. As discussed above, the theory of gravity has undergone many revisions, which have resulted in paradigm shifts.

A paradigm shift occurred in the field of fashion scholarship during the middle of the 20th century. Prior, fashion was understood as a “trickle down” phenomenon (further explained in Chapter 3) where trends originated in the upper classes and were adopted by subsequently lower classes. However, in the 1960s a new phenomenon was observed, that the reverse was happening. This resulted in a reevaluation of the assumptions surrounding fashion knowledge and resulted in new theories. Additionally, more recently there has been a shift in the perception of clothing of traditional, non-western societies. It was often recited that fashion only existed in westernized societies and that non-western societies did not “have” fashion (e.g., Blumer, 1968; Flugel, 1930; Sapir, 1931; Simmel, 1904). It was argued that the appearance and dress of tribal and traditional cultures did not change but were static. However, the detailed study of traditional cultures has altered this perception (e.g., Cannon, 1998; Craik, 1994; Dalby, 1993; Dwyer, 2000; Jirousek; 1997; Nag, 1991; Niessen, 2007).

True theories should not be confused with lay theories. Lay theories are popular explanations for phenomena and have none to little evidentiary support but are believed to be factual. Hemline theory is a lay theory that is thought to link the height of women’s skirt and dress hemlines to the economy. Some people believe the theory explains that when hemlines rise or fall the stock market will rise or fall. Other people believe that when the stock markets rises or falls so too will hemlines. Hemline theory is a lay theory that is often repeated by people who follow stock markets or follow fashion; however, its veracity and predictive validity is questionable. There is some evidence to corroborate a connection between stocks and hemlines but not enough to provide a definitive conclusion about the relationship (see Figure 1.2).

Hemlines have long been thought to be related to the stock market, an idea first proposed by economist George Taylor (Nystrom, 1928). He speculated that in good economic times women wore shorter skirts to reveal their silk stockings, which were a luxurious expense at the time; whereas in difficult economic times women wore longer skirts to hide the fact they were not wearing silk stockings. Researcher Mary Ann Mabry (1971) examined this theory and provided descriptive and statistical evidence of a relationship between the American stock market and hemlines. Mabry’s overview of the decades reveals some preliminary data on the subject. In the 1900s and 1910s hemlines reached the ankle. In the 1920s, during a time of prosperity in the United States, hemlines moved from the ankle to the knee. When the New York Stock Exchange crashed in 1929 and the world plummeted into a depression, hemlines fell to the mid-calf. World War II brought restrictions on fabric and goods but hemlines remained at the knee for the duration of the war. After the war, Christian Dior introduced a new silhouette which became known as the New Look. The 1950s were also a time of prosperity for the United States. Hemlines were below the knee and remained there until the mid-1950s. In 1957, Balenciaga introduced the sack dress which was designed with a higher hemline. The 1960s were also a time of prosperity and the mini-skirt was offered by Cardin, Courrèges and Mary Quant.

While descriptive evidence points to some possible support of this theory, Mabry (1971) further analyzed quantitative data for additional verification. She collected data from four fashion magazines and correlated the hemline length with data from the New York Stock Exchange from 1921 to 1971. She concluded that there is a positive relationship between hemline and stock market fluctuations. “Although there were several occasions when hemlines and stock market averages did not fluctuate hand-in-hand, enough indications were given to illustrate the similar movements of the two” (p. 66).

Mabry’s research points to a statistical correlation between hemlines and the stock market. A correlation means two things happen at the same time, but does not mean there is necessarily a direct relationship. There may be a third variable that connects the two or it may just be coincidence. For example, imagine that you get headaches frequently and your doctor tells you to keep a record of when you get headaches. You do and notice that you get headaches on Mondays. You surmise that there is a connection or correlation between the two but this does not explain why you get headaches on a regular schedule. It may be that on Mondays you have a weekly lunch with a client and she wears perfume to which you are allergic. Or it may be that you are allergic to an ingredient in the food you eat at lunch. Or it may be that you are recovering from a wild weekend. Whatever the reason may be, there is an unknown variable that is causing the headaches. Likewise, there could be an unknown variable related to both stock markets and hemlines which has not yet been identified. Nonetheless, the connection has been repeated as evidence of a direct relationship among the population and treated as fact.

Economists Marjolein van Baardwijk and Philip Hans Franses further examined the connection between the stock market and hemlines for the time period 1921–2009. Their research yielded results that suggest a change in economic conditions precedes a change in hemlines by three years. Thus, they argue, a downtown in the economy will result in lower hemlines three years later. However, their methodology was highly dubious. They compared images in the French fashion magazines with economic data from the National Bureau of Economic Research that constituted a “world business cycle.” Thus, while their statistical analysis might be accurate, their conclusions are likely based on faulty assumptions.

While this theory may have had some validity in the early 20th century, beginning in the 1960s the number of simultaneous fashion trends began to multiply. Today, any hemline length can be found in the market; Boho chic with long flowing skirts is found alongside super-short micro-skirts. Nonetheless, people continue to perpetrate the myth of a connection between hemlines and the stock market.

So what is the point of theory and why do we need it or what can we do with it? The study of fashion helps us to understand how people interact and relate to each other. Clothing is a medium that represents genders, sexuality, race, ethnicity, class, psychology, society, culture, business, politics, philosophy, and so forth. By studying clothing and fashion we can interpret notions that have implications and impact on our daily lives, both locally and globally. Academic researchers of fashion and clothing strive to understand the way the world works and can use clothing as a lens to peer into other constructs. They use past and present phenomena to explain events and predict future styles, trends, actions, and behaviors related to clothing and fashion.

Researchers of fashion also can help current and future fashion professionals by interpreting their research findings into theories, models, frameworks, and constructs that have the potential to improve business professionals’ goals. For most businesses the goals are to serve their clients in order to accrue a profit. While some business professionals may rely on their own intuition, their own experience, and formulate their own theories, models, frameworks, and constructs, academic findings can offer additional insight, different interpretations, and new venues for thought and action. For example, a retailer may have observed that fashion trends change from season to season in a linear direction, but without the understanding why, how, and when they will change, the retailer is left with only a partial understanding. All fashion professionals use—or should use—some degree of fashion forecasting in order to predict trends their clients will want. Most fashion professionals—designers, merchandisers, retailers, stylists, journalists, etc.—are not only working in the present to satisfy current client needs, but also planning to satisfy future needs. This takes a degree of research and insight; theories, models, frameworks, and constructs help to guide the decisions.

Accurate, validated theories are important to the field of fashion because they help guide decisions. As a burgeoning fashion professional, you will need to make decisions about products you wish to develop, buy, market, and sell in the future. Without sound reasoning (e.g., theory) your predictions of what will become a fashion are more likely to fail. For the fashion forecaster, the designer, or the merchandiser, this is a vital tool in planning, designing, manufacturing, and promoting collections. If you are able to predict that women will want higher hemlines over the next three years you have a better chance of designing saleable clothing. If you are able to predict that men will respond positively to the color mint green next spring you have a better chance of reaping profits and a better chance of becoming a leader in the fashion business. Predictions made on the basis of theory likely prove more accurate than predictions made on guesses or hunches.

Researchers in the sciences frequently investigate the relationship between independent variables and dependent variables. Independent variables are assumed to have an effect on dependent variables. That is, an independent variable can result in a change in the dependent variable by some connective means. Researchers make predictions about the relationship between two or more variables based on theory and develop hypotheses. The hypotheses are then tested. It will require many tests and different research studies to establish the validity of a theory.

In social scientific disciplines variables are studied using experiment, survey, observation, or interview. An experiment is commonly used in Psychology and is a manipulation whereby a condition of the independent variable is changed. The change can result in a change in the dependent variable. Experiment is the only way to deduce a causal relationship: A caused B because of C. For example, if you wanted to test if a new medicine (the independent variable) works on acne (the dependent variable), you would recruit a sample (participants) and divide them into two groups. One group would receive the acne medicine and one group would not (this is called the control group). If at the end of your experimental period, you observe that there is a difference in the level of acne in the group receiving the medicine you can surmise that the medicine caused the difference. If, however, you do not observe a difference in acne between the two groups at the end of the experimental period, you can surmise that the medicine had no influence.

A variation of an experiment can be to manipulate an original item, such as a photograph. For example, if you wanted to test if eye color affects perceptions of attractiveness, you could use duplicates of the same headshot of a person and change the eye color in each of the images. Because all else remains constant and only the eye color is altered, it is logical to assume that differences of perceived attractiveness are due to eye color. You then obtain a random sample of subjects (participants) and show them one of the images and ask them to rate the person’s attractiveness on a scale. You continue this procedure and show many different people any of the images until all images have been reviewed and evaluated many times over (the number of times depends on your experimental design). After you collected all the data you analyze and find that a majority of your respondents find green eyes the most attractive. You can then surmise that a change in eye color causes a change in perceived attractiveness. Researcher R. Kelly Aune (1999) used an experiment to study how perfume affects perceptions of attractiveness and competence. Aune’s method included participants being briefly interviewed by different people who were wearing differing amounts of perfume. When the interview was finished the interviewee evaluated the interviewer using a questionnaire. Aune analyzed the results to conclude that the amount of perfume an interviewer wore influenced perceived attractiveness and competence of the wearer.

Another method to test hypotheses is survey. Survey is common in Sociology and is used to generalize findings to the larger public when employed correctly. A survey involves collecting data via questionnaires. The questionnaires are frequently measures of a variable that have been tested and verified as accurate and reliable. After randomly-selected participants have completed your questionnaire, the data are analyzed using statistics. Statistical analysis can provide evidence of similarity/difference, correlation, or prediction. For example, if you wanted to find out if body image (independent variable) affects self-esteem (dependent variable) you would find effective and established scales of both variables, include them in a questionnaire, and give them to participants. Using statistical analysis you may find that a negative body image predicts low self-esteem, and conversely, that a positive body image predicts high self-esteem. Sophisticated statistical analyses such as structural equation modeling yield models that show pathways and connections between many variables. Researchers Alan C. Geller, Graham Colditz, Susan Oliveria, et al. (2002) employed the survey method to study tanning behaviors among children and adolescents. They gave questionnaires to more than 10,000 participants, then analyzed their responses using statistical procedures to identify sun protection attitudes and practices among their sample. Given the large sample size they had in their study they can make inferences based on their findings to the population at large.

Observation is also a method to record data. It is common in the field of Anthropology and is sometimes called field research or participant observation and involves the researcher seeing events or people in their natural environment. The researcher records their observations and interprets them to make conclusions. Participant observation often elicits information that the researcher would not obtain via survey or experiment because the participant may be unaware of the behavior or may not be truthful or accurate about it. For example, if you wanted to examine shopping behavior during a major sale you could go to a shopping mall and watch people. You may observe that people line up outside the store early the day of the sale, argue with other customers, and yell at sales people. In this method you may also interview or ask shoppers questions to understand their motivations or behavior. You could then surmise that a major sale affects customers’ behavior. Fashion scholar Joanne Entwistle (2008) used this method to study masculinity among male models. She used interviews with models and bookers (the modeling agency’s employee who books models) and sat in the offices of modeling agencies to observe models to evaluate and understand how male models negotiate their identity relative to gender and sexuality.

Researchers can also study behavior via examining history. Relationships between variables are assumed but not necessarily tested as in the case of experiment or survey. Historians often use primary and secondary sources to gather their information. Primary sources are original documents or artifacts, while secondary sources have already examined the primary sources and made conclusions or interpretations. For example, if you wanted to study the dress of cowboys in the 1880s, you could examine clothing that is preserved in museums and diaries written by cowboys (primary sources) as well as contemporary books and documentary films about cowboys. Historian Rachel K. Pannabecker (1996) used the historic method to study the incorporation of ribbon—a European product—into the authentic dress of the Great Lakes Native Americans. She used diaries, memorandums, accounting records, moccasins and other clothing items to examine the concept of cultural authentication (explained further in Chapter 4). A variation of this method was employed by fashion researcher Andrew Reilly (2008) to test Historic Continuity theory (explained in further detail in Chapter 2). Reilly used secondary sources—more than 2800 advertising images in magazines from 1900 to 1999—to evaluate how details of menswear evolve over time.

Many people assume fashion is clothing, and although this may be true in a sense, fashion is actually much more complex and meaningful. Consider the following quotes about fashion:

•Fashion is “cultural technology that is purpose-built for specific locations” (Craik, 1994, p. xi).

•“Fashion, in a sense is change” (Wilson, 1985, p. 3) [italics original].

•Fashion is “a variation in an understood sequence, as a departure from the immediately preceding mode” (Sapir, 1931, p. 141).

•Fashion is “the eternal reoccurrence of the new” (Benjamin, 2003, p. 179).

•“Fashion is a general mechanism, logic or ideology that, among other things, applies to the area of clothing” (Svendsen, 2006, p. 12).

•“Fashion is a specific form of social change, independent of any particular object” (Lipovetsky, 1994, p. 16).

•“Fashion is not simply a change of styles of dress and adornment, but rather a systematic, structured and deliberate pattern of style change” (Polhemus, 2011, p.37).

•Fashion is “a prevailing custom, usage or style” (Merriam-Webster, 2013b, n.p.).

Based on these definitions, we can surmise the following: fashion is (a) an intangible force (b) that is manifested in tangible products, (c) that represent newness relative to prior fashion products, (d) are adopted by a group of people, and (e) are reflections of society and culture. Using this perspective, we can apply the concept of fashion to different products and industries.

In this text we need to distinguish between the terms clothing, dress, and fashion because these words are not interchangeable in fashion theory. Clothing is a product made out of a textile that is worn on the body; a shirt is an article of clothing. Dress includes three elements: (1) any item worn on the body (e.g., clothing, accessories); (2) any modification to the body (e.g., tanning, dieting, tattooing, hair styles); and (3) anything appended to the body (e.g., handbags, crutches, dog leashes, fans). A fashion is a form of dress or article of clothing that has or will become popular; bobbed hair was a fashion in the 1920s for women. Fashion is also a social process whereby an item of clothing or dress is adopted by many people; the fashion of the 1990s was influenced by music.

All dress is not fashion and fashion is not always dress. As discussed above, fashion is a process and can therefore be applied to industries beyond the clothing industry. The concept of fashion can be applied to any object or behavior or way of thinking. There is fashion in automobiles; in the late 1950s cars with fins were fashionable. There is fashion in the type of pets people own; in the 1920s it was fashionable to own German shepherds. There is even fashion in the type of social media used; MySpace fell out of fashion in favor of Facebook.

Specific to the fashion industry, the forces of popular acceptance influence areas other than clothing as well. Jewelry choices fluctuate with regard to gemstone, material, and design. Facial make-up and nail polish alter seasonably with changes to products, hues, application techniques, and overall aesthetics. Styles of shoes and belts wax and wane with specific details, as do lingerie, handbags, hosiery, hairstyles, fragrances, body shape, and body hair. And items like backpacks, skateboards, bikes, and electronic devices (e.g., smart phones and their covers) have become “fashion” items that are easily replaced.

Fashion is most often related to clothing because of the nature of the industry and its products. Forms of dress, such as apparel, jewelry, and accessories, are quicker to design, produce, and sell than other products. Automobiles take years from design to manufacture to popular acceptance and are costly to develop, produce, and buy. Furniture is expensive to manufacture, and replace or change frequently. Pets become beloved family members and people do not sell or replace them at whim for a new pet. But dress, being more affordable than other items such as cars or home interiors, is available to all people. In addition, dress is closer to the body making it more intimate and personal than one’s choice in refrigerator color. And most everyone wears some form of dress, making it highly common. Thus, dress is a good source for the study of the process of fashion.

In westernized, capitalist societies, fashion as a process is a peculiar concept because products created as fashions are designed to have a short lifespan. They are designed to be popular for only a brief period of time. They are designed to die. This is known as planned obsolescence and it is the foundation of the western fashion system. If a trend does not end then there is no need to replace it. Fashions are created to sell in one season, have a brief and hopefully prosperous life, and then be discarded for something new.

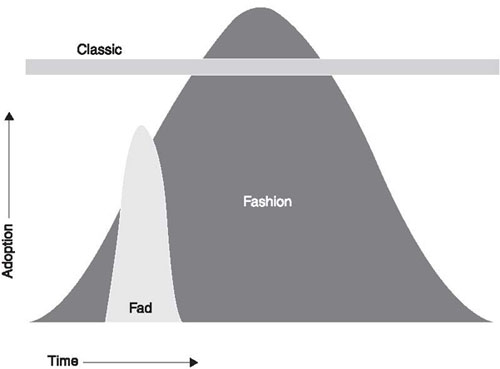

The life of a fashion trend is viewed as a bell-curve, with the passage of time represented on the bottom and adoption represented on the left side (see Figure 1.3). At first, the item is adopted by a few people, but adoption increases with time until the market has been saturated and the item is at its most popular. Then adoption of the item declines until it eventually tapers out. A fashion trend is not to be confused with a fashion fad or classic. Fads are quick and sudden bursts of popularity and exist for a short period of time, such as calf-toning sneakers or feather extensions for hair in the early 2010s. Classics, in general, do not fluctuate in popularity and are found from season to season and year to year with little or no change. Examples of classic apparel items include Levi 501 jeans, khaki pants, and white t-shirts.

Fashion is often believed to be the domain of western culture, whereas clothing from other regions of the world was termed “ethnic” or “costume” or “traditional” in the erroneous belief that dress from other cultures did not change or follow trends; that is, other cultures were viewed as not having fashion. Fashion scholar Sandra Niessen (2007) argued that people were designated as without fashion as a means of categorizing us versus them, modern versus non-modern. Fashion from the western perspective was viewed as symptomatic of modernity, newness, and technology. Designating people as without fashion designated them as barbaric.1 Contemporary researchers that argue that non-western societies have fashion trends are contrary to early fashion theorists who argued that fashion exists only in societies with social structure, where change is rapid, and “time” is acknowledged differently (e.g., Blumer, 1968; Flugel, 1930; Sapir, 1931; Simmel, 1904). Primitive cultures were thought to be “stuck” in time with little progress or adaption and thus provide a feeling of superiority for westerners. This perspective likely stems from research by early anthropologists who visited tribal cultures for limited amounts of time and were not there long enough to witness change as defined by western standards (Niessen, 2007).

Likewise, fashion scholar Jennifer Craik (1994) also argued that the ethnocentric view of fashion as a Euro/American phenomenon is inaccurate. She argued that the idea that non-western people have static modes of dress is incorrect. Craik (2009) noted that the Chola women of La Paz, Bolivia have a distinctive type of dress that is both customary and fashionable. The skirts they wear are called polleras and women usually wear multiple polleras at one time. Each year new styles of pollera in new fabrics and decorative appliques are offered, thus creating a fashion cycle where old styles are abandoned and new styles adopted. Craik (1994) similarly argued that fashion exists among the Mount Hagen residents of Papua New Guinea. During an annual festival, tribal members gather for a celebration and adorn themselves with unique headdresses, made of such varied materials as feathers, bones, flowers, birds, fauna, fur, teeth, and human hair. The materials are combined to create unique looks that are a combination of traditional aesthetics and individual preference. “There is no doubt that such radiant displays are not just the uniform of custom but exhibit individual interpretations, innovations, and adaptions” (Craik, 2009, p. 55). Thus, Craik argued, fashion also exists in this traditional community.

Ethno-historian Charlotte Jirousek (1997) questioned the difference between fashion and traditional dress as well and examined the clothing changes among men in the Turkish village of Çömlekçi. Western forms of dress were first introduced by the late 19th century. In the 1920s, Western dress forms were originally intended by the governing bodies to “modernize” the people of Turkey, but the residents of Çömlekçi, rather, appropriated the new forms and made them part of their culture. In 1964, although village men wore western clothing, “the mode of dress remained essential traditional, in spite of outward appearance of modernization” (p. 208). Tailored slacks were accompanied by white, long-sleeve shirts (buttoned to the collar by older men and unbuttoned by younger men) along with hand-knitted sweater vests, over which suit jackets were worn. A brimless hat, such as a golf cap or a skullcap was worn (the hat needed to be brimless to align with religious dictates that the head must be covered during prayer and the wearer must touch his head to the ground during prayer), though some men wore fedoras. Frequently, a musket was carried as an accessory. A village tailor made the clothing but by the 1960s ready-to-wear shirts were available. By the 1980s, villagers were exposed to different forms of dress through television and the tourists who visited the village. By the 1990s, there was a multiplicity of dress mass-manufactured dress styles, including jeans, tank tops, t-shirts, shorts, sweaters, and suit jacket, worn mostly by the younger generation. The older generation continued to wear their traditional clothing.

Jirousek (1997) argued that as Turkey sought to reform and modernize at the beginning of the 20th century, “a set of European fashion system garments was adopted into a traditional dress system and continued in the initial form, essentially without further change, throughout much of [the 20th] century … The superficial appearance of westernization of dress in fact does not justify the assumption that the wearer is westernized” (p. 212). Thus, the garments had become culturally authenticated (see Chapter 4), but they were still in a traditional dress system. The system began to change to a mass-fashion system with the arrival of electricity, television, tourists, and later by the introduction of mass-produced fabrics and ready-to-wear clothing. By the mid-1990s, Jirousek asserts the transition to a mass-fashion system was virtually complete; older village men wore their traditional suits in the village but changed to a fashionable look when going to town, while the younger men wore fashionable attire regardless of location.

In addition to the above, fashion has been noted in garments that have typically been described as static: the sari of India (Dwyer, 2000), the sari of Bengal (Nag, 1991), the dress of Canadian Native peoples (Cannon, 1998), the kimono of Japan (Dalby, 1993), and the dress of China during the Ming period (Brook, 1999). Thus, while the western fashions system may be the most discussed in texts and literature, and probably the best known given globalization, other systems of fashion exist. Contrary to popular assumption and belief, fashion exists outside of industrial societies as well. Although this book is intended for students who likely will work in a western-styled fashion system, examples of fashion from non-western or non-industrialized societies will also be discussed.

In the same vein that fabric has been cut, folded, manipulated, and decorated to create aesthetic effects so too has the body been cut, folded, manipulated, and decorated. One of the most common body fashions is to reshape its silhouette using undergarments. The corset is one of the early inventions that helped women achieve a fashionable figure, be it an hourglass shape of slim waist with curved bust and hips or a slim silhouette that compressed the bust and hips into a tubular shape. Historically, corsets were made of fabric that was stiffened with animal bones, metal or plastic. Laces in the front or back were used to tighten areas in order to reshape the body. Women were not alone in wearing corsets; men too were fond of what the corset could do to one’s figure and these were especially prominent on men’s bodies in the early 19th century. Although corsets may have fallen out of fashion, other silhouette-modifying creations, such as girdles, brassieres, and high-compression underwear and shirts, helped men and women achieve the desired silhouette. For example, the pannier, popular in 18th century Europe, emphasized a woman’s hips (see Figure 1.4).

Decorating the body with tattoos is another example of fashion. Whereas tattoos were once reserved for tribal cultures, avant-garde artists, and criminals, by the 1990s they were becoming fashionable in Europe and American societies. Although some people may argue that tattoos cannot be fashion because of their permanence (Polhemus, 1994; Curry, 1993), dress scholar Llewellyn Negrin (2008) argues that tattoos have become fashionable and notes different styles of tattoos are fashionable at different times. Negrin wrote:

[A]lthough the physically permanent nature of tattoos may seem to mitigate against their use as fashion icons, their semiotic multivalency led to their widespread employment in the marketing of men’s styles. Whereas tattoos are often used by individuals in a bid to fix their identity by permanently imprinting it onto their skin, it is their very un-fixity of meaning that has led to their appropriation by the fashion and advertising industries. (pp. 334–335)

Another way the body can be aesthetically altered is by tanning or bleaching. Tanning darkens the skin tone while bleaching lightens the skin. Tanning can be done naturally by exposing the skin to the sun’s rays, or artificially by exposing the skin to ultraviolet light or by applying creams and sprays that can cosmetically darken the skin. Bleaching can be achieved by applying creams or dermatological products to the skin. People of all races, geographic locations, and classes participate in tanning or bleaching and the reasons vary (Christopher, 2012). Some people like the aesthetic of darkened or lightened skin because it is fashionable, some use darkened or lightened skin as a way to signal status (e.g., people who work in fields are tanned, so lighter skin symbolizes a life of luxury indoors; lighter skin symbolizes people who work indoors, so darker skin symbolizes lounging on the beach); and still others view it as a way to differentiate one group of people from another.

Other ways the body has been altered for fashionable purposes include branding, piercing, hair removal, hair extension, breast enlargement, liposuction, circumcision, dieting, slenderizing undergarments, protein shakes, working out, and body building. In all these examples it was the body that was transformed, thus making it a vital component in the examination of dress and fashion change.

Put a pot of water on the stove and turn the burner on high heat. Watch it. It will take a few minutes to start to see some activity but eventually you will see little bubbles—like champagne bubbles—start to form. There will not be many at first but more will develop and then they will get larger. Soon there will be big bubbles, but the entire pot will not be boiling until one specific moment when suddenly—wham!—the entire pot of water is boiling. Malcolm Gladwell (2002) termed this the “tipping point.” It is the point at which nothing becomes something.

Gladwell argued that fashion trends can be thought of as epidemics; rather than the element studied being a contagion, the element is contagious behavior. He argued there are similarities in the way a disease and a fashion trend spread. The tipping point is when a trend gets noticed. He identified three rules:

1.The Law of the Few. Some people have more influence than others. These people are connectors, mavens, and salespeople. Connectors know lots of people and connect disparate groups. They transfer information or knowledge from one group to another. Mavens have the ability to start epidemics by talking. They are well-informed and are viewed as sources of information. Gladwell likened them to “information brokers” who use word-of-mouth to pass along interesting or important information. Their aim is not personal gain but simply to help people. Salespeople are critical to the epidemic because they are the ones who can persuade others to take action. They are at the cusp of the tipping point.

2.The Stickiness Factor. Messages need to be “sticky.” There needs to be something memorable about the information. In fashion a new design or way of styling needs to be memorable. Sometimes this comes in the garment itself, in the way it is styled, or in the way it is presented in promotions.

3.The Power of Context. Epidemics are sensitive to context. They are dependent on the environment as to whether they will spread or die. Gladwell wrote, “an epidemic can be reversed, can be tipped, by tinkering with the smallest details of the immediate environment” (p. 146).

Gladwell cites Hushpuppy shoes to illustrate his concept. By 1994 Hushpuppy shoes were hopelessly out of fashion after rampant success in the 1950s and 1960s, and the company was about to close. Perhaps for the fact they were so out-of-date that some chic youths in the East Village of New York City began to buy them at vintage stores. Those youths were noticed by others who also began buying Hushpuppy shoes at vintage stores too. Soon designers such as Isaac Mizrahi, John Bartlett, and Anna Sui incorporated Hushpuppy shoes into their collections, resulting in the shoes and company being revived from the brink of extinction and the iconic shoes becoming fashionable again. In this case, the youth who began wearing the vintage shoes again were a few of the connectors, those that followed their example were mavens, and fashion designers were salespeople. The message was particularly sticky; they were so out of fashion they had to be noticed. The context was that the fashion culture was fascinated with vintage clothing and ironic, retro looks. By 1995 the interest in Hushpuppy shoes had tipped and became a legitimate trend.

Semiotics is the study of signs and sign systems. Anything can be a sign and represent an idea or concept; a heart can represent love, a gold band on a finger can represent marriage, an olive branch can represent peace. Linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1966) argued that a sign is made of a signified and a signifier; the signifier is a sound-image while the signified is what it represents. For our purposes we will extend the sound-image to include visual objects. The connection between signifier and signified is governed by a code. For example, the color of a cowboy’s hat in Western movies is coded. The hat is the signifier and its meaning is the signified. In classic Western movies, the cowboys in white hats (the signifier) are considered good (the signified), whereas cowboys in black hats (the signifier) are typically bad (the signified). This coding creates a short-hand for the observer; without knowing anything about a character the viewer can immediately recognize the heroes from the villains.

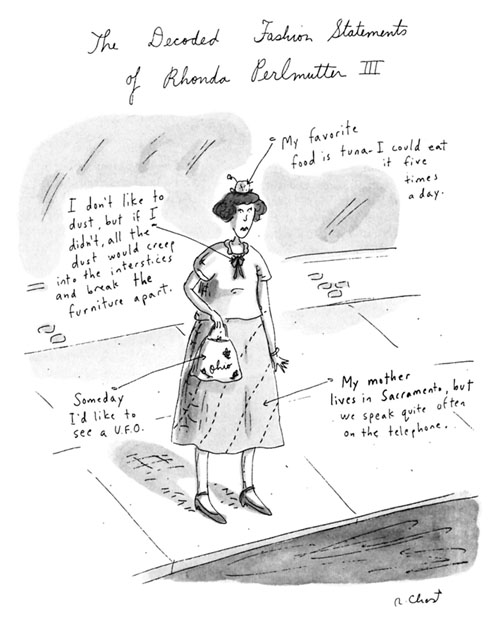

In general, all dress can be considered semiotic because all dress is embedded with meaning; however, people can interpret the specific meaning differently because codes are a product of enculturation and socialization. A fur coat can mean different things to different people. It can mean warmth and protection from snow; it can mean luxury and status; it can mean death and cruelty. One’s history as an Eskimo, fashionista, or animal-rights activist colors the way in which the fur is interpreted. See Figure 1.5.

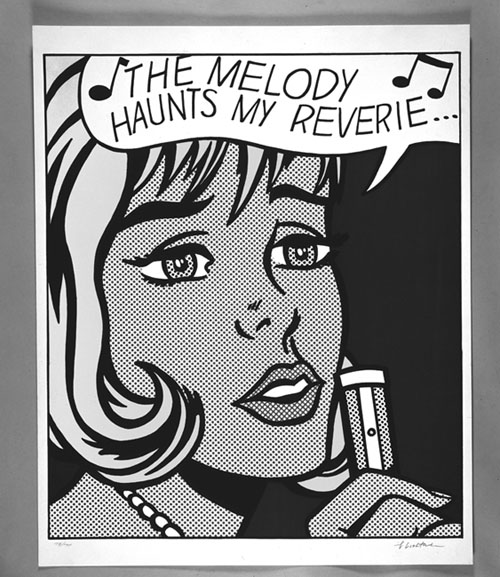

In the past century the world has transitioned from the “modern” era to the “postmodern” era in what can be considered a paradigm shift. Modernism is the belief in rationalism and universal truth. Those who subscribe to modern thought believe in tradition and that there is only one correct way to do something. Postmodernism is a reaction to modernism. Rather than accepting traditions as a universal truth, the postmodern perspective questions them. For example, a modern painting depicts people in a realistic way, but a postmodern painting might depict the same people but in a rendering that is highly stylized, such as the comic-strip style in Roy Lichtenstein’s Reverie (see Figure 1.6). A modern sculpture might depict a bust of a famous person, but a postmodern artist might depict a famous word, such as Robert Indiana’s LOVE sculpture where the letters of the word are the sculpture. A modern film might show the beginning, middle, and end of a story in that order, but a postmodern film might reverse or jumble the order; in Memento the first scene of the film is the last scene of the story and the film is shown in reverse; in Pulp Fiction the first scene begins in the middle of the story.

When we look at dress we can see differences between modern and postmodern perspectives. From a modern perspective there are expected rules to follow: do not wear white shoes after Labor Day2; do not wear plaid with polka-dots; do not wear pajamas to school. From a postmodern perspective these rules are challenged, disrupted, and violated: white is worn after Labor Day, violating a long-standing rule of fashion; plaid and polka-dots are combined to provide a new aesthetic experience; pajamas are worn to school, challenging social conventions.

Figure 1.5 This cartoon lampoons the semiotic nature of dress; nonetheless it illustrates varied signifiers and signifieds of clothing. Roz Chast/The New Yorker Collection/www.cartoonbank.com.

Dress scholar Marcia Morgado (1996) noted that rejection of authority is central to postmodern philosophy. By virtue of rejecting authority, questioning begins. Questioning is challenging the traditional, acceptable modes of dress (Damhorst, 2005) such as wearing white shoes after Labor Day. In the modern era rules dictated what styles of dress were acceptable to wear based on one’s status, age, occupation, and gender. But in the postmodern era the rules are disrupted to create unique, individual compositions; a wedding dress could be worn with combat boots or expensive diamond jewelry could be worn with sweatpants. Sometimes you might hear the term mixing used synonymously with questioning, such as creating a multi-cultural aesthetic by mixing different dress items from different ethnic communities. Questioning can also lead to irony, another element that is typical of postmodern fashion. For example, modern fashion would have rules against adults accessorizing with children’s toys but in the postmodern era the irony of an adult wearing jewelry made of children’s toys is appreciated (see Figure 1.7).

Another form of questioning is the use of androgyny. Androgyny comes from a Greek word meaning “man and woman” and hence androgyny is the blending together of masculinity and femininity. It should not be confused with unisex which is the absence of masculinity and femininity. Overalls are unisex but not necessarily androgynous. There are a number of ways that androgyny can be incorporated into fashion: feminine fabrics, such as lace, could be pared with masculine fabrics, such as leather; a tailored men’s jacket could be paired with a flowing skirt; a man with masculine facial features can sport soft, flowing curls of hair, or a woman with curved, delicate facial features can sport short, cropped hair. Postmodernism is a reaction to modernism’s rules, so androgyny challenges modernist conventions of femininity and masculinity by violating the rules by mixing them. The punk, goth, and grunge subcultures and the subsequent trends they inspired contained androgynous elements. Additionally, models like Erika Linder, and Harmony Boucher, and Andrej Pejic exemplify the androgynous aesthetic and are frequently hired for men’s and women’s fashion shows and advertisements.

Another important element of postmodern fashion is valuing an item for its aesthetics rather than its symbolic meaning (Morgado, 1996). Wearing a crucifix or rosary or Star of David around one’s neck would be considered postmodern if the wearer wears it because it is “cool” or “stylish” rather than because it symbolizes a religious conviction. In the Jewish faith a Kabbalah bracelet is a red string tied around the left wrist and is linked to ancient, mystical teachings. It is believed to protect the wearer from harm. The Kabbalah bracelet became a fashion statement for many in the 2000s after celebrities like Madonna embraced the faith and adopted the bracelet. Followers of celebrity culture adopted the red bracelet with little understanding of its meaning, but rather liked the look. Another instance of placing aesthetics over symbolism is when people adopted “tribal” tattoos as fashion without understanding the cultural significance of the design. Often, tribal tattoos carry meaning with them such as achieving adulthood or accomplishing a goal and are frequently sacred. When people began adopting “cool designs” for their body art they were practicing postmodern fashion.

Scholars have also noted that we appear to be entering into a new phase and have used many different labels to call this new era, including altermodermism (Bourriaud, 2009), hypermodernity (Lipovetsky, 2005), performatism (Eschelman, 2000, 2001), automodernity (Samuels, 2008), digimodernism (Kirby, 2009), and metamodernism (Vermeulen & van den Akker, 2010). Morgado (in press) analyzed five of the prevailing concepts, used the popular term “post-postmodernism” as an umbrella term, and identified elements of the new era relevant to fashion and dress. She surmised the following: post-postmodernist dress includes new designs that are the result of collaboration between business (e.g., the retail store or brand) and consumers; excessive consumption for the pleasure of consumption but mixed with anxiety about personal impact on the environment and anxiety about personal debt; styles that utilize cyber technology; random mixture of aesthetic elements and principles, and infantile or childish styles for adults. Examples of post-postmodern dress include NIKEiD from Nike where consumers can select styles, colors, and patterns to create a custom-designed shoe; shopping for fast fashion3 items that one will wear only a few times before discarding them while anxious about the impact this will have on the environment and personal debt; cyberpunk and steampunk styles that blend technology with fashionable components; and Hello Kitty accessories for adults. However, Morgado noted that other than cyberpunk and steampunk, these fashion examples can also be explained by postmodernism, and therefore if we are entering a new era we are at the cusp of it and have not seen post-postmodernism’s full impact on fashion as of yet.

In academia, fashion has often been considered the inferior relative to the more established disciplines of engineering, mathematics, chemistry, physiology, psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Many people consider fashion frivolous. It is considered unnecessary. It is considered unworthy of serious attention. This is because fashion has long been considered to be the domain of women and therefore silly. Indeed, men are often thought to “not have fashion” and when they do they are European, and if not European, they are black, Asian, Latino, or a race other than white, and if they are white, they are gay, and if they are not gay but straight, they are an oddity. But a cultural shift in the 1990s began to look at fashion differently. Museums and documentaries explained the deeper meaning and significance of fashion and universities were offering rigorous programs in fashion theory. While the perception of fashion has changed somewhat, there is still considerable distance between “respectable” disciplines and fashion curriculums.

Two academic traditions exist in the study of fashion, although there is overlap between them at times: Fashion Studies and Clothing and Textiles. Fashion Studies came from established disciplines such as art, art history, humanities, and museum curation. These disciplines were respected fields, although the study of fashion tended to be marginalized. However, in the 21st century, Fashion Studies programs started to form that examined fashion from a unified perspective. Meanwhile, the Clothing and Textiles perspective originated in Home Economics departments in the United States. Beginning in the 1850s, young men were educated in agricultural programs, whereas young women were educated in cooking, household maintenance, child rearing, and sewing. The Clothing and Textiles discipline grew out of the sewing curriculum. In the 1960s, the discipline shifted from matters of the home to matters of industry, and branched into merchandising, marketing, retail management, textiles, history and social-psychology of dress and appearance. Fashion scholar Erfat Tseëlon (2012) categorized those who study fashion into two different groups: fashion natives and fashion migrants. Fashion natives work with artifacts of dress to “chronicle, classify, categorize [and] describe uses” (p. 4), whereas fashion migrants come from social science fields and examine abstract ideas related to dress, such “meanings, functions, [and] reasons” of dress (p. 4). Today, generally, Fashion Studies programs focus on critique, analysis, and interpretation of meanings of fashion, whereas Clothing and Textiles programs examine industry components, although there is overlap among some scholars and researchers in the field. In this text, examples from both perspectives are included.

The sections of this text are organized based on a continuum developed by fashion scholar Jean Hamilton (1997). Hamilton argued that fashion occurs at two levels: at the micro, or individual level, and at the macro, or group level. Spanning these levels are four systems that each contribute to the process of fashion: individual, social, cultural and the fashion system.

In Chapter 1 you were introduced to theory and basic terms and concepts. In Chapter 2 you will read about the individual influence to understand the role unique people have in the fashion process. In Chapter 3 you will read about social influence to understand how groups of people innovate and react to fashions. In Chapter 4 you will read about culture to understand what types of cultures support and do not support fashion systems. In Chapter 5 you will read about the fashion system to understand the business of fashion. And finally Chapter 6 will include examples of fashion failures and conclude the book. After completing this text you will have a good foundation for understanding how, where, why, and when fashion exists.

BOXED CASE 1.1. RUDD/LENNON MODEL OF BODY AESTHETICS

Creating a visual appearance is more complex than one would think. The act of dressing appears to be simply putting on clothes, but underneath this straightforward behavior lay a constellation of variables that influence our dress selections. The Rudd/Lennon model of body aesthetics helps us to understand these influences (Reilly & Rudd, 2009, p. 236; see Figure 1.8). Cultural, social, and psychological variables influence the aesthetic creation. That creation (i.e., the visual appearance) is pre-tested and feedback is gathered from other people. Based on this feedback you do nothing, you change your appearance, you change your personal standard of what you consider attractive, or you try to change the cultural standard of what is considered attractive. This model can be used to understand how and why people dress themselves.

For example, if you were dressing for a job interview you would start by selecting your apparel based on the cultural ideal which leads to the box marked “created appearance.” The cultural ideal for a job interview is conservative dress in muted or dark colors. Your selection is influenced by comparing yourself with others and anxiety. You decide to wear a suit made of navy pinstripe wool and paired with a matching white and blue stripe shirt and red tie. You receive feedback from your roommate and mother; your roommate says “I don’t like it” and your mother says “That’s an odd shirt to wear—the pattern is too busy.” You realize at this point that your best option is to change your shirt into a plain white one (thus, you accepted a standard and are trying harder to achieve it). Wearing your new shirt, you receive additional feedback from your roommate (“You look good”) and your mother (“That’s better”) and you are ready for your interview.

As you examine the model consider your own style of dressing—which path did you take?

BOXED CASE 1.2. MASLOW’S HIERARCHY AND FASHION

Some cultures or organizations have strict rules as to what people can and cannot wear—such as dress codes enforced by businesses, schools, fraternities, or sororities4 (belonging). Some groups of people may not have strict rules about what to wear but have a certain look that identifies them, such as punks or motorcycle clubs or cowboys; in order to belong one must dress like them (love/belonging). Some people choose items of dress because it makes them feel good about themselves or gives them status (esteem), such as wearing gold. Some individuals may want to express their individuality and potential by creating appearances that reflect their inner-being (actualization).

People wear fashion for reasons different from wearing clothing. One way to understand the different motivations that people have for wearing clothing versus fashion is to use a model developed by psychologist Abraham Maslow (1943). Maslow developed a hierarchy of needs and postulated that people pass through a series of stages to meet their needs. According to Maslow, the first need is physiological, the second need is safety, the third need is belonging, the fourth need is esteem, and the final need is self-actualization. If we take this concept and apply it to dress, we can see that dress can satisfy the need for safety, such as keeping you warm or dry or protected from insects. But as people strive to belong to groups and to feel good about themselves, the role of dress can shift from clothing to fashion. Maslow’s hierarchy is a good way to organize dress and analyze different motives. It can be a useful tool for professionals in fashion, advertising, promotion, and image-consulting.

BOXED CASE 1.3. FASHION IS A MEME

A meme is an idea or style that is replicated and spread among people. Slogans can be a meme, like “Have a Coke and a Smile” or McDonald’s “I’m lovin’ it,” or Nike’s “Just do it!” Quotes can be meme, like “Life is like a box of chocolates” from Forest Gump (1994) or “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn!” from Gone with the Wind (1939) or “This ain’t my first time at the rodeo” from Mommie Dearest (1981). Memes can also be more complex, like conspiracy theories, fairy tales, or behavior (such as tapping the breast twice followed by flashing a peace sign.) They become part of the popular culture and are passed from person to person very quickly in different formats. These quotes or ideas have been replicated on t-shirts, mugs, bumper stickers, refrigerator magnets, lapel pins, texts, email addresses, decorative plates, television shows, songs, jokes and more.

You read about Gladwell’s concept of the tipping point—that fashion can be like a contagion or virus that spreads rapidly. His idea is similar to that of a meme. It is passed from person to person, in different forms, rapidly. It is replicated and spreads out like a virus. Fashion can spread from person to person, neighborhood to neighborhood, from city to city, from region to region, and can theoretically and metaphorically be contagious.

Fashion is a process whereby an item—such as a form of clothing or dress—becomes popularized during a specific period of time. Fashion is accepted first by a few people and grows in acceptance with time until it has reached a saturation point, and then it declines in popularity. Fashion should not be confused with clothing. Not all fashion is clothing, and not all clothing is fashion; some clothing does not conform to the “rules” of fashion and some items that are not even dress-related are fashionable.

Fashion theory attempts to explain why some items become popular while other items do not. Fashion theory is studied by academics and industry professionals to explain personality, social movements, cultural ideals, business practices. It is hoped that, with accurate theories of fashion, business can make informed decisions about what to create, produce, sell, and market. Theories, ideas, and concepts are created to explain fashion. Some theories, ideas, and concepts are validated while others have been modified. New theories or modifications to existing theories are often the result of a paradigm shift. Like clothing trends, fashion theories can also become fashionable themselves in their popularity and use.

•Classic

•Clothing

•Code

•Concept

•Conceptual framework

•Connectors

•Dress

•Fad

•Fashion

•Hypothesis

•Law

•Law of the few

•Mavens

•Meme

•Modern

•Paradigm

•Planned obsolescence

•Postmodern

•Post-postmodern

•Questioning

•Salespeople

•Semiotics

•Signified

•Signifier

•Stickiness factor

•Taxonomy

•Theory

•Theoretical framework

•Tipping point

•Trend

1.When do you think a trend becomes noticed? When do you notice a trend?

2.Is your mode of dress modern, postmodern, or post-postmodern?

3.According to Gladwell there are three groups of people important to fashion: connectors, mavens, and sales people. Which are you?

4.Name different types of questioning you have noticed in people’s modes of dress. Which of these were aesthetic and which were symbolic?

1.Create a taxonomy to categorize the clothing items found in your wardrobe. Examples of categories can be: fiber (natural, manufactured, mixed), country where made, design (solid, stripe, or patterned), color, style (casual, professional, special occasion), etc. After you have completed your inventory, do you see any gaps or areas where you have more of one category than others?

2.Collect images of fashion items and categorize them as modern, postmodern, or post-postmodern. Identify their characteristics. How would you redesign one of the modern items to make it postmodern, or post-postmodern?

3.Collect advertisements of dress and group into two groups: clothing and fashion. Within each group, arrange the advertisements according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. How do the groupings compare? Does clothing have more images in one level than fashion? Why do you think advertisers choose to market products differently and how do you think consumers react to these different marketing strategies?

4.Bring in an item of dress from your closet and discuss with the class its semiotic elements. What are the signifiers and signifieds? Are there any elements that might be misinterpreted or read differently by other people?

____________________ Notes ____________________

1. Indeed, fashion historian Valerie Steele (1998) has noted the myth of Parisian fashion as superior to other fashions by designating as barbaric non-Parisians who did not dress as well as Parisians.

2. Labor Day is an American holiday celebrated in the beginning of each September. It is frequently considered to be the beginning of the Fall season. With regard to fashion, white shoes are considered summer shoes and worn between Memorial Day in May (the start of the summer season) and Labor Day. Likewise, alcoholic drinks followed a similar cycle; clear alcohol (e.g., vodka) in summer, dark alcohol (e.g., rum) in winter.

3. Fast fashion is a retail concept where inexpensive trendy clothing is produced and sold quickly. The fact that the clothing is poorly made is negated by the fact that it is inexpensive and can be replaced easily.

4. Fraternities and sororities are social organizations at many colleges in the United States. Potential members, or pledges, apply to become members and undergo a period of initiation before they are accepted.

__________________ Further reading __________________

Bovone, L. (2006). Urban style cultures and urban cultural production in Milan: Postmodern identity and the transformation of fashion. Poetics, 34 (6), 370–382.

Goldsmith, R. E., Flynn, L. R., & Moore, M. A. (1996). The self-concept of fashion leaders. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 14 (4), 242–248.

Gordon, B. (2009). American denim: Blue jeans and their multiple layers of meaning. In P. McNeil and V. Karaminas (eds) The Men’s Fashion Reader (331–340). Oxford: Berg.

Hagen, K. (2008). Irony and ambivalence: Postmodernist issues in the fashion world. In P. Giuntini & K. Hagen (eds) Garb: A Fashion and Culture Reader (pp. 101–110). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Holloman, L. O. (1991). Black sororities and fraternities: A case study in clothing symbolism. In Patricia A. Cunningham & Susan Voso Lab (eds) Dress and Popular Culture (pp. 46–60). Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

Reilly, A., & Rudd, N. A. (2009). Social anxiety as predictor of personal aesthetic among women. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 27 (3), 227–239.