Uniqueness is an important concept in initiating and propelling fashion trends. Some people do not want to dress like others. Some people want to be different—to show they do not follow social conventions, are individualistic, or are artistic—and to do this they purposefully avoid wearing the current fashions or trends. What is considered unique can be something that is similar to the current trend but slightly different. If wide collars are in vogue they might wear a very wide collar, thus advancing a fashion trend (see “Historic Continuity theory”, this chapter p. 45). Or what is considered unique can be something completely different, like wearing silver jewelry when gold jewelry is the trend.

The body is also a site for people to exhibit uniqueness and in doing so have instigated new fashion trends. In the middle of the 20th century, in Europe and the United States, having a tattoo made a person unique, but by the end of the century singular tattoos were common. People who desired a different look found new ways to aesthetically alter their skin. Singular tattoos were followed by numerous tattoos and sleeves (see irezumi in Chapter 4) and glow-in-the-dark tattoos. Likewise, pierced ear lobes had become commonplace, so people who desired uniqueness turned to piercing ear cartilage, eyebrows, navels, nipples, wrists and necks. By the 21st century, a new trend had emerged—medical-grade metal pieces were implanted under the skin to give a new dimension to the body and ear plugs were stretching the earlobe to new proportions. These changes demonstrated how something once considered unique, once popularized, needs to be replaced with a new concept or form.

Fashion is often a curious dance between two opposing forces—the desire to fit in and the desire to be different. As a concept uniqueness helps us to understand why some fashions die and some new ones begin. Some people—like fashion innovators and fashion leaders—do not want to wear what everyone else is wearing. When a market becomes saturated with a style they strive to find something different, and by doing so sometimes launch a new trend. The desire to not follow the fashion trends—or anti-fashion—is also a strong influence on many people’s choice of dress. They may feel fashion is frivolous or consumerist and purposefully wear clothing that is not in fashion, but ironically what is not in fashion at this particular moment can be alluring to others, who then adopt it and disseminate it to others, thereby continuing the fashion life-cycle.

Fashion innovators and fashion leaders are individuals who create new styles or communicate a new style early in its life-cycle (see Figure 2.1). By virtue of being seen in the new style or telling others about it, they help to instigate a new trend. Similarly, an individual can kill a trend by declaring it dead. For example, celebrities such as actress Katharine Hepburn, actress Catherine Deneuve, actress Catherine Zeta Jones, the Duchess of Cambridge Katherine Windsor, model Kate Moss, and singer Katy Perry have influenced fashion greatly. Yet, one does not need to be an international celebrity to influence fashion; average consumers do it every day in what they choose and do not choose to purchase.

The fashion curve presented in Chapter 1 aligns with the type of person who adopts a trend. In the beginning, fashion leaders are the first group of people to adopt the trend (Rogers, 1962). Fashion innovators are people who take a chance with wearing something new or unique, be it a new product or a new way of wearing an existing product. Often this can be a celebrity or a well-known person or someone who is considered an authority on fashion. This person is seen wearing the style which in turn disseminates it to other people, such as fashion communicators. Fashion communicators are viewed as authorities on fashion and help to popularize the growing trend by wearing it and talking about it. For example, the style might be mentioned in a magazine or seen on a television show or at a red carpet event. Note the similarities between these terms and Gladwell’s terms of mavens and salespeople (as discussed in Chapter 1). Next, the population majority and population minority adopt the item, followed by fashion laggards until finally the trend expires. This system of communicating fashion trends from one group to another is known as the adoption and diffusion model (Rogers, 1962).

This chapter examines how the individual interacts with fashion. The Public, Private, and Secret Self model is presented first in order to understand people’s different levels of expression. The model posits that people dress to reveal different facets of their life—from the public self that anyone can see to the secret self that is hidden from others. This theory is followed by the concept of body image—the way a person perceives their body and what they do about their body affects how they dress it or the methods he or she may take to change it. Body image is a significant issue in fashion right now as the fashion industry is criticized for creating unrealistic body standards that affect people negatively. Aesthetic Perception and Learning theory explains that people need to learn to understand or appreciate a new design or style of dressing in order to accept it. Two theories are presented that touch upon the role of boredom in fashion change. When people become bored with a style they look for a new way to dress, as explained by the theories of shifting erogenous zones and historic continuity. Lastly, Symbolic Interaction theory explains how the individual interacts with society in order to create meaning.

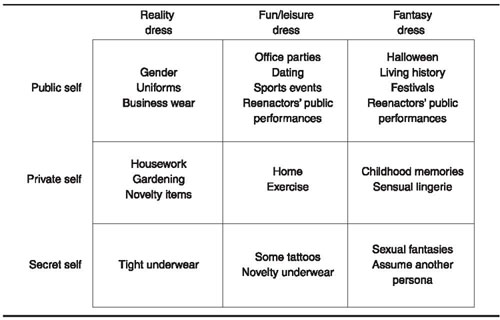

The Public, Private, and Secret Self model is a taxonomy for categorizing different types of dress at different levels of expression. The model was originally proposed by dress scholar Joanne Eicher (1981) who based her work on research developed by sociologist Gregory Stone (1965). Stone argued that two categories of dress exist: reality and fantasy. Reality dressing, or anticipatory socialization as he termed it, is dressing for a realistic job you hope to hold one day—such as wearing a business suit in the hopes of working for a bank. Fantastic socialization, however, is dressing for a job that is not realistic, but imaginary, like dressing as a Stormtrooper from Star Wars. Eicher (1981) furthered this idea and divided dress into public, private, and secret levels. It was later expanded by Eicher and Miller (1994).

The taxonomy divides dress into three types (reality, fun/leisure, and fantasy). Reality dress is realistic attire that may be related to one’s gender, work, or hobbies. Fun/leisure dress is worn outside of work situations and may be dress for dating, exercise, or sporting evenings. Fantasy dress is escapist and may include costumes and sexual fantasies. These three categories are crossed with three aspects of the self (public, private, and secret). The public self is the part of us that anyone can see, and usually includes clothing we wear to work, run errands, or in professional situations. The private self is revealed to friends and family but is likely not seen by the general public. The secret self is hidden from others or may be revealed only to intimates. According to the taxonomy, the level of self interacts with the type of dress to create nine distinct cells: public × reality, public × fun/leisure, public × fantasy, etc. This grid helps to analyze situations related to dress (see Table 2.1).

Institutions, such as workplaces, governments, and religions often administer rules for dressing the public self. Businesses determine dress codes, such as jacket and tie for banking professions or uniforms for police officers. Branded retailers, like Abercrombie and Fitch or Top Shop, may require their employees to dress in the clothing they sell. Some governments have general rules of public dressing, such as outlawing nudity in public places, but other governments may be more specific. In Saudi Arabia, all female citizens must cover their bodies. This rule is both governmental and religious. In the Islamic faith, women wear an abaya, or outer coat, when in public. Islamic faith dictates that women dress modestly in public and cover themselves so that men unrelated to them may not gaze upon them. The abaya is usually worn with a veil. The niqa¯?b is a veil common in Arabian countries; it is a black square of cloth that covers the head and face, with a slit for the eyes. The burqa or chadri is a form of abaya common in central Asian countries; it covers the body and contains a grill or net for the eyes. This conforms to the idea of dressing at the public level. However, in private, the wearer may remove the public dress to reveal the private level of dress. This level of dress is only seen by female friends or female and male relatives, and may be fashionable, but is always modest.

Table 2.1 The Public, Private, and Secret Self model divides dress into nine categories.

Source: Eicher J. B., & Miller, K. A. (1994), Dress and the public, private and secret self: Revisiting a model. ITAA Proceedings , Proceedings of the International Textile and Apparel Association, Inc., p. 145.

Dressing for the secret self can be hidden and not seen by anyone else; generally, undergarments fall into this category. A man who likes wearing women’s underwear because he likes the silky feel but does not let anyone know of his preference is dressing at the secret self level. But the secret self can also be revealed to others, typically in the form of fantasy or escapist dress. A person may wear a superhero costume publically, but keep secret the desire to be the superhero (Miller-Spillman, 2013).

Anthropologist and Star Wars fan Eirik Saethre has fond memories of playing with Star Wars action figures when he was a child. He enjoyed the films and liked the imaginative play associated with the toys. As an adult he found a group of other adults, the 501st Legion, who recreate and dress as Stormtroopers. Although the 501st Legion demonstrates in public, Saethre, and likely others, harbor the secret desire to be the action figure. He proceeded to build a suit and soon learned there were specific guidelines to follow. By following the guidelines, Saethre not only was constructing a costume, he was also constructing a new identity. He wrote, “In constructing a kit, prospective members [of the 501st Legion] were also constructing a boundary between themselves and the ‘average person’ or ‘casual fan’” (2013, p. 498). He argued that in the process of acquiring a specific language and specific aesthetic code, he developed a new identity for himself. This new identity coincided with the secret self x fantasy cell of the Public, Private, and Secret Self model: assuming another persona.

Body image is defined as “a person’s perceptions, thoughts, and feelings about his or her body” (Grogan, 2008, 3). How a person perceives his or her body affects how he or she feels about it and consequently how he or she dresses it. Mostly, people dress to hide perceived flaws and use aesthetics (see this chapter) to draw attention away from the perceived flaw and to something else. A person may camouflage acne scars with make-up, wear slimming undergarments to achieve a smoother silhouette, or wear a boldly-colored scarf to draw attention to his or her face. Body image is linked to self-esteem, such that the better/worse a person feels about his or her body the better/worse his or her self-esteem (Grogan, 2008; Pope, Phillips & Olivardia, 2000). Feeling poor about one’s body can result in body dissatisfaction. When people are dissatisfied with their bodies they take measures to change them.

The processes people take in order to create an appearance are called appearance management behaviors. Appearance management behaviors are classified into two categories: routine and non-routine (Rudd & Lennon, 2000). Routine appearance management behaviors are frequent procedures that carry little to no health risk, such as ironing clothing, wearing make-up, and exercise. Non-routine appearance management behaviors are engaged in less frequently and carry some degree of risk or pain, such as tattooing, liposuction, anorexia, bulimia, or chronic dieting. Reilly and Rudd (2009) found non-routine appearance management behaviors to be related to social anxiety among women, such that as women experience more social anxiety they are more likely to use a risky or painful procedure. Reilly and Rudd believe that non-routine appearance management behaviors are perceived to provide a quick fix to the perceived problem.

Sometimes, a person’s perceptions of their body may not reflect reality which can lead to appearance-related disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or chronic dieting. Anorexia nervosa is the refusal to eat food while bulimia nervosa is bingeing on food and then vomiting it; both result in unhealthy weight loss. It is estimated that 1% of the female population in general suffer with an eating disorder (Anorexia Bulimia Care, n.d.), while other research estimates that 20 million women in the United States suffer with an eating disorder at some point in their life (Wade, Keski-Rahkonen, & Hudson, 2011). While there are numerous reasons that a person may suffer from an eating disorder (e.g., abuse, trauma, teasing, bullying) many people also blame the fashion industry because it perpetrates an unrealistic thin standard for women. Model Coco Rocha recalls being told by modeling agents, “The look this year is anorexic. We don’t want you to be anorexic, just look it” (Misener, 2011). She was 15 at the time. Researchers found that between 2001 and 2002 the average dimension of British women’s waist had increased by 7 inches since 1951; in 1951 the average waist size was 27 inches, but in 2013 it was 34 inches, while bust size remained relatively the same (Winter & McDermott, 2013). However, models have become thinner since the 1960s. In the 1950s idealized female forms were voluptuous and hourglass, but in the 1960s slim models like Twiggy began to appear and models became thinner and thinner (Grogan, 2008). Grogan writes, in the mid–1990s, “designers and magazine editors often chose to use extremely thin models such as Kate Moss to advertise their clothes and beauty products. The late 1990s saw the rise of ’heroin chic’; that is fashion houses made very thin models up to look like stereotypical heroin users” (p. 23). Former Australian Vogue editor Kirstie Clements (2013) recounts models skipping meals, using an intravenous (IV) drip, and eating tissues to stave off hunger pains. Striving to be thin (and hired) has resulted in models dying from lack of nutrition. In 1996 American model Margaux Hemingway died, in 2006 Brazilian model Ana Carolina Reston died, in 2006 Uruguayan model Lusiel Ramos died, in 2007 her sister Eliana Ramos died, in 2010 French model Isabel Caro died. Their deaths have been attributed to eating disorders.

Part of the drive for thinness can be attributed to the fashion industry using younger and younger models. Established, “mature” models in their early 20s are competing with models in their teens, whose bodies have yet to fully develop. In an effort to compete the older models try extreme measures to stay thin. At the age of 13 Elle Fanning became a model for Marc Jacobs and at the age of 14 Hailee Steinfeld became a model for Miu Miu. In 2011 French Vogue used model Thylane Blondeau in one of its issues. She wore sexy clothing. Her hair was done up and her face applied with make-up. Her poses were provocative. She was 10 years old.

Public outcry has resulted in some changes in the modeling industry. Madrid Fashion Week instituted a minimum body mass index (BMI, a ratio of height to weight that indicates healthiness), as have Milan Fashion Week and Israel Fashion Week. In 2012 the international Vogue magazines vowed to ban models under the age of 16 and any model with signs of an eating disorder.

Men also are prone to body image issues and can suffer from body dissatisfaction. Prior to the 1990s, men were generally portrayed in the media as having average bodies, with a few exceptions. Underwear was advertised sans body, in packages and not on models. One of the first underwear ads to feature a muscular model was Calvin Klein’s racy underwear campaign featuring a very muscular and toned Mark Wahlberg. More fashion campaigns using muscular, almost-nude men followed. In addition, performance-enhancements, such as anabolic steroids, have contributed to unprecedented muscle growth and size. But men needed not to just be muscular, they also needed to be lean. Thus, men became dissatisfied with their bodies two ways—the desire to lose weight and the desire to gain weight (Pope, Phillips, & Olivardia, 2000).

It is estimated that 10–15% of people who suffer from eating disorders are men (National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, n.d.). The percentage may actually be higher because men are socialized to not worry about their appearance and if they do to not talk about it. In addition to anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and chronic dieting, men with body dissatisfaction also can suffer from muscle dysmorphia, sometimes called “reverse anorexia.” Men with muscle dysmorphia see their bodies as under-developed, where in actuality their bodies are very muscular. They often engage in regimens of obsessive weight-training in order to increase muscle size.

Just as with women, there are many reasons why men experience appearance-related disorders, including the fashion industry and affiliated media. In the early 2000s Hedi Slimane began designing “skinny” silhouettes for Dior Homme, which became highly fashionable and replicated by many other designers in the industry. The skinny look shifted the fashionable male body aesthetic from big and buff to slim. Today, as men strive to fit into skinny clothes and are impacted by fashion advertisements of skinny models, they no doubt internalize the look and seek ways to alter their body shape.

Aesthetic perception and learning is based on the assumption that people need to learn to appreciate and understand beauty. Aesthetics is the rules of beauty. Every culture, society, or individual has their own beliefs as to what makes something beautiful or ugly or somewhere in between. Designers work with the elements of aesthetics to create their looks: color, line, form, space, and texture. These elements can be used in different ways, known as principles: repetition, sequence, alternation, gradation, transition, contrast, proportion and balance. Thus, colors can be alternated in a striped shirt, textures can contrast in a skirt, or lines can transition from horizontal or vertical in a blazer. The theory posits people have to learn to understand the interplay of elements and principles in order to appreciate beauty. A person may not like vertical stripes personally, but understanding that according to westernized rules of aesthetics, a vertical line elongates the body and a long, lean body is valued over a wide body can change the person’s perception of vertical stripes. A person may not like the color green but understanding that a green coat on a person with red hair brightens the hair color may be appreciated.

Researchers and scholars have devised different models to explain how aesthetics are perceived. Dress scholar Marilyn Delong (1998) approaches aesthetics as formal, expressive, and symbolic qualities. Formal qualities are the elements and principles of design, expressive qualities are the emotions associated with wearing the apparel product, and symbolic qualities are meanings associated with the apparel product. The combination of these three influences the wearer’s appreciation of the garment.

Using a pearl necklace as an example, we can analyze the formal, expressive, and symbolic qualities to better appreciate its aesthetics. The formal qualities of the pearl necklace are repeated round shape, lustrous white color, and smooth texture. The expressive qualities might be making the wearer feel sophisticated. The symbolic qualities might be reference to the month in which the wearer was born (the birthstone for the month of June is pearl). Thus, the pearl necklace is perceived as a combination of three qualities.

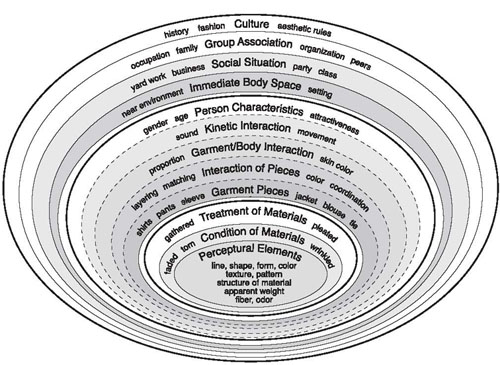

Another scholar of the social-psychology of dress, Mary Lynn Damhorst (1989, 2005), developed a model that envisions aesthetic perception as a series of embedded elements or networks (see Figure 2.2). At the center of the model are the perceptual elements such as line, shape, form, color, etc. This is encompassed by the condition of the material. The condition of the material is encompassed by the treatment of the materials, and so on. Using this model we understand that the aesthetic elements are situated within concentric series of cultural, social, and personal spheres.

When a new collection is offered by a designer the consumer (or viewer) has to understand how the aesthetics relate to each other. A viewer learns to appreciate a design that is different (but not too different) from previous designs. Repeated exposure to the design helps the appreciation and acceptance process (see mere exposure hypothesis in Chapter 5).

In the 1950s, during which Dior’s New Look was sweeping across Europe and North America, British designers were advocating for simpler styles and wanted to establish “good” standards of taste (see Chapter 3 for more on the concept of taste). The Council for Industrial Design was one group established to educate consumers and fashion industry professionals about appropriate designs. “The programme of regulation was managed by institutions … and involved in campaigning to change the attitudes of both manufactures and the consumer, and the production of propaganda ‘aimed at familiarizing the public with that new concept “design”’” (Partington, 1992, p. 153, quoting Sparke, 1986, p. 65). The aim of the program, as Partington notes, was to educate working-class women on tasteful aesthetics and promote useful, utilitarian designs over the elaborate, decorative New Look fashion. Sensible styles were displayed in public exhibitions and publications explained how to combine aesthetics appropriately. Some developments of the utilitarian style became popular, like the shirtwaister and multipurpose suit. “As the consumer of fashion goods, the working-class women were being educated in the skills of ‘good taste’ (restraint, practicality, etc.)” (Partington, 1992, p. 155).

Likewise, in the 1990s fashion designers began offering collections that were simpler from the previous decade. The 1980s were awash with frenzied patterns of bold strokes and vivid colors. Designers like Nolan Miller and Christian Lacroix used an abundance of sequins and rhinestones and yards of shiny fabrics to dress their clients. The look was obvious, in-your-face luxe; it screamed glamour; it was far from subtle. But in the 1990s designers like Donna Karan, Calvin Klein, and Giorgio Armani were offering collections that were much simpler, with the flash and decoration removed. These designers had always offered simper clothing, but perceptions of aesthetics and its symbolic qualities shifted and people began wearing plain clothes. Some people supposed this trend to be boring. Rather, they needed to examine the aesthetics and relative meaning to appreciate the look. “Designers wanted to move away from the ostentation and the perceived bad taste of the gilt logo which was seen as too blatant a symbol of wealth and excess” (Arnold, 2000, p. 169). The simplified cuts from Donna Karan, Calvin Klein, Giorgio Armani and others, made from fabrics of neutral colors like black, navy, and white, were a new aesthetic that needed to be learned to be appreciated. Through magazine and newspaper editorials, advertisements, and retail promotions, people soon realized/learned that simplicity equaled luxury and luxury equaled an emphasis on fabric, cut, and silhouette, not on decoration and adornment.

Historian James Laver (1969) first proposed a Theory of Shifting Erogenous Zones to explain why fashions go in and out of style. He was influenced by psychologist J. C. Flugel (1930) who argued that the naked body is anti-erotic. The naked body is anti-erotic because it leaves nothing to the imagination. The imagination is more powerful than reality. For example, in horror films, storylines where the monster is not depicted or only slightly depicted on screen tend to be more frightening because your imagination can conjure the type of monster that scares you. Simultaneously, the anticipation of seeing the monster builds. Frequently, when the monster is finally seen there is a bit of a disappointment because it does not match your expectations. Likewise, a clothed body allows for imagination and anticipation. Based on this premise, Laver argued that styles of women’s fashion change in order to reveal different body parts. As the body part is exposed, it becomes eroticized. Showing what was previously hidden becomes exciting until it becomes a common sight. When a particular body part becomes overexposed it is no longer sexually enticing, so a new area of the body is exposed.

In the early 1900s women’s breasts were thrust up with corsets and brassieres and their legs were covered, but in the 1920s women’s legs were eroticized when they threw off their floor-length dresses for loose dresses that rose to the knee, yet the breast was covered and flattened. In the 1930s hemlines dropped but the back of women was frequently exposed. Thus, what became eroticized shifted over time. (See Figures 2.3, 2.4, and 2.5.)

Figure 2.3 The Ohio State University Historic Costume and Textiles Collection, courtesy of Dr. Anne Bissonnette.

Figure 2.4 University of Hawai‘i Historic Costume Museum.

Figure 2.5 The Theory of Shifting Erogenous Zones posits that fashions change in order to expose different body parts. In the 1930s the back was fashionable to expose (2.3), while this asymmetrical dress from the 1970s shows how an exposed shoulder was fashionable (2.4); by the 2010s the leg became the new focal point (2.5). Nata Sha/Shutterstock.com.

Yet, fashion historian Valerie Steele (1985) noted that the theory can also apply to covered areas of the body that are enhanced or exaggerated through clothing, not just what is revealed. Poulaines, also called Crakows (they were popular in Crakow, Poland), were very long, pointed men’s shoes fashionable in 15th century Europe. One could either read the shoe as an erotic fascination with feet or symbolic substitution for the size of the wearer’s phallus. In the 16th century, the phallus itself was also emphasized by using a codpiece, a piece of fabric that covered the groin where men’s hose were joined together. Likewise, women’s body parts were emphasized similarly. The bustle of the 19th century brought attention to the derrière, while shoulder pads highlighted shoulders in the 1940s and 1980s, and the waist was (de)emphasized via corsets in the 1950s. Like the examples of the exposed body, apparel fashions have changed to force attention on areas that are considered erotic or fetishistic.

Laver’s argument was based on the social structure of gender and the economic dependence of women on men. His argument was that women must keep men interested in order to financially support them and they accomplish this by exposing different parts of their body. Some people argue that the theory is dead because women have more economic independence than before, that with today’s styles the entire body has been over exposed, and that there are reasons other than sexuality to adopt and discard styles of dress. While these arguments may be true, one cannot argue that the desire to attract a mate is gone. The theory is still valid in its basic premise that fashions change to alleviate boredom and overexposure, whether or not the motivation is to attract a spouse. In the 1980s midcrop shirts that revealed toned abdomens were popular. In the early 2010s asymmetrical tops for women revealed sexy shoulders. In fact, in the early 2010s Old Navy advertised the “high-water” pants with a campaign that asked people to “show off their sexy ankles.” Perhaps we have come full-circle from the antebellum days when the ankle was erotic in the pre-Civil War Southern United States?

With change in the economic status of women—and men now needing to offer women more than a monetary enticement—men’s fashion has seen changes in exposing erogenous zones. Shirts changed from t-shirts to tank tops to expose arms, and necklines shifted from crew to v-neck to deep-v to display male cleavage (or “he-vage”). Shorts, as they rose and fell from hot-pants to mid-thigh to knee-length to Capri-length served to draw focus to the groin, thigh, knee, and calf, respectively. Likewise, sock length also called attention to particular body parts; the sockless or no-see-sock look reveals ankles, while different lengths focus attention on the calf or knee.

With today’s fashions focusing on heightened body exposure, the body can still be eroticized through tattoos and piercings. Both are erotic features of adornment because they draw attention to the flesh and by consequence to a portion of the body. The location of tattoos on the body have shifted over time and in recent decades it has been fashionable for men to have tattoos around one’s bicep, lower back, and upper arm (i.e., irezumi) (Reilly, in press). Popularity in piercing sites, too, changed from ear lobes to ear cartilage, to ear tragus, to nipples, navels and back of neck. It can be argued that the locations of the tattoos or piercings change because of overexposure and the need for something unique.

One can see a relationship between this theory and Historic Continuity theory (this chapter) in that both theories argue that people become bored with the status quo and seek change. The theory of historic continuity argues that this change needs to be small, resulting in an evolution of fashion, while the theory of shifting erogenous zones argues a new body part needs to be exposed.

Fashion is a careful balance between wearing what is similar to others but also what is different. People desire change (in order to be unique or to alleviate boredom) but they are more comfortable with small changes than large changes. A large change is too abrupt and too different. If you were in a hot sauna and then suddenly jumped into an icy pond, you would be in shock. It is similar with fashion; going from one extreme to another is too jolting, but a gradual change is tolerable. Styles will change in small ways in order to satisfy the need for difference but not alienate the psyche that needs familiarity.

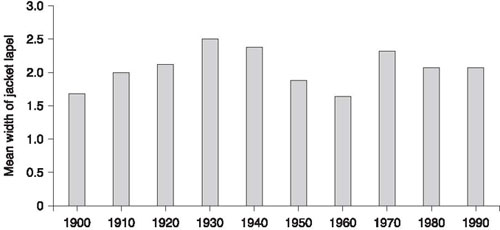

Historic Continuity theory explains that a detail about fashion will change over seasons until it has reached its maximum (or minimum) and then reverse order until it reaches its minimum (or maximum). It will continue on this pendulum and create fashion cycles. A skirt’s hemline will continue to rise until it cannot be raised anymore (it has reached its endpoint), then reverse order and continue to lower until it cannot fall anymore (reached another endpoint), and reverse again. Anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber (1919) was one of the first researchers to examine the phenomenon of fashion change using Historic Continuity theory and concluded that styles change slowly from one extreme to another. He likened this to a pendulum on a clock swinging back and forth. He found that a skirt length will recur approximately at 35 year intervals and that skirt width returned after an interval of 100 years.

Other researchers have continued this line of research and examined skirt length (Curran, 1999), décolleté, waist and skirt length/width (Lowe & Lowe, 1982, 1985; Richardson & Kroeber, 1940), men’s hair styles (Pedersen, 2001; Robinson, 1976), and details of men’s pants, shirts, and jackets (Reilly, 2007). (See Figure 2.6.) In general, they have found fashion change tends to follow a path; men’s shirt collars widen and slim down; hemlines rise and fall; waists rise and fall. Researchers John W. G. Lowe and Elizabeth D. Lowe (1985) found that although dimensions (e.g., silhouettes) are cyclical, style is not. In addition, they argued, dimensions may not return to the maximum before reversing. Andrew Reilly (2007) similarly argued that with regard to menswear, fashion dimensions are evolutionary though not cyclical, meaning that they evolve from the prior fashion but do not recur at regular intervals.

This phenomenon can be observed in other fashion details as well. Observe the fit of pants. In the late 1970s “French jeans” were extraordinarily tight but through the 1980s the fit of jeans had become more relaxed until the 1990s when they were loose and baggy. Then the trend reversed and they became skin-tight again by the 2010s. Adults were even shopping in children and young adult departments in order to get the tightest pair of jeans they could find. The arrival of jeggings (leggings that were printed with a denim look) helped facilitate the desire for a tight silhouette. Then in 2011 Dior and Lanvin offered an extremely radical silhouette. One Dior pair of men’s pants had a leg opening of 24 inches. Granted, the shift was too radical to be adopted en masse, but those desirous of change began to wear pants that had a looser fit than before. By 2013 Ferragamo also offered wide legged pants for men. Corollary to this is the waist location of pants. In the 1980s, a high waist was fashionable but it dropped by the 1990s. Low pants were in and showing off one’s underwear or derrière was a common feature. By 2012, the waistline of pants had fallen so low that it could not fall any lower and still maintain coverage so the waistline began to rise, with Prada offering early versions of this trend.

There is an exception to the rule that change must be gradual. Twice in history there has been a radical change that did not follow the projected trend. After the French Revolution (1787–1799), women’s fashions changed from ornate, large, cumbersome styles to flowing, softer styles. After World War II (1939–1945), women’s fashion changed from restricted, masculine and tubular silhouettes to wide, voluminous, and feminine styles. Both of these abrupt changes in fashion were due to significant changes in social and political structure. France had changed from a monarchy to a democracy after 12 years of brutal battles, and after World War II the western world was emerging from five years of restrictions on fabric and an upset in gender relationships. Thus, the exception is that during times of great change or social upheaval there may be a sudden upheaval in the direction of a fashion trend.

Symbolic Interaction theory acts as a bridge between the individual and society. It explains how the individual makes sense of meanings and symbols via social interaction. Philosopher George Herbert Mead (1967) is credited with the development of this theory though students of Mead such as Herbert Blumer (1969) have greatly contributed to the theory and established three principles of symbolic interaction: 1. People give meaning to things and behave towards the thing based on the meaning they give. 2. Meanings are based on social interaction. 3. Meanings are interpreted by the person. This theory means that people use symbols to interact with each other and those symbols are created by, and interpreted by, the person. The theory posits that people are not interacting with the object per se, but with what they believe the object means. Thus, when you meet a stranger in a police uniform, you are reacting to what the police uniform means to you, not necessarily the uniform itself. To some people the uniform could mean safety; to others it could mean oppression.

If we tie this idea to fashion we can surmise that people ascribe meanings to articles of dress. Recall in the discussion of semiotics (Chapter 1, p. 19) that communication is derived from a signifier and a signified, which is governed by a code. With this in mind, consider this example. You are vacationing in Honolulu and become lost. You need directions for how to get back to your hotel and you come across two people: a woman in a police uniform and a woman in a floral Hawaiian shirt, khaki shorts, and sandals worn with black socks. You interpret the woman in the uniform as a member of the police force, based on prior experience. Similarly, based on experience you interpret the other woman as a tourist. Your past experience informs you that police are knowledgeable, but that tourists are not because they do not live in the area. You ask the police officer where to find your hotel and she gives you accurate directions. This social interaction reinforces your belief that people in police uniforms are knowledgeable, and aligns with Davis’ (1982) assertion that meanings need to be maintained or revised. If you had asked to the woman you perceive to be a tourist and she gave you accurate directions, your assumptions about the meaning of Hawaiian shirts worn with sandals and socks would be challenged and you would likely revise your interpretation; tourists might be knowledgeable.

Interpreting the meaning of dress also depends on the context. In the above example, the context was a vacation spot. This likely influenced the perception of police officers and tourists. However, if the context was different—a different historical time, a different culture—like Nazi Germany, your interpretation of police officers might be different—fear rather than trust.

Likewise, context also helps to decipher ambiguous messages. The word “read” is ambiguous by itself; is it a future tense verb or past tense verb? You need the context of other words to decipher its meaning: “Last night I read a book” or “Tonight I will read a book.” Likewise, situational context helps you decipher the meaning of particular dress. In European and American societies, wedding dresses are traditionally white; the color white is associated with purity. If you saw a bride in a red wedding dress, you might be confused because red is associated with wantonness (among other interpretations). You might think, what is the meaning of a red wedding dress; why is it not white? The context of the situation will help resolve the ambiguity. You notice that the ceremony is spoken in Mandarin Chinese and the bride appears to be of Chinese ethnicity, and then you remember red is the traditional color for wedding dresses in many Asian countries because the color red is associated with happiness. The context provided you the cues you needed to interpret the clothing.

Dress scholars Susan Kaiser, Richard Nagasawa, and Sandra Hutton (1997) surmise that ambivalence and ambiguity are important components that contribute to changing trends. Ambivalence is the feeling of being conflicted or drawn in multiple directions. You might feel ambivalence on a Friday night when you want to go to see a movie but also want to study for an exam. An ambiguity, as discussed, is the state of having multiple interpretations or meanings; the intended meaning is not clear or is confusing. The combination of both ambivalence and ambiguity allows for multiple interpretations and a “dialogue” with society to determine which interpretation will prevail. If an interpretation prevails, the authors argue, then the style will become a fashion; if an interpretation does not prevail and a style remains ambiguous in its meaning, then the style will be discarded.

Through the 20th century, the black leather jacket held both ambivalent and ambiguous meanings in American and European societies due to shifting changes in male identity. Meanings generated by wearing the black leather jacket were due to:

[A] degree of creative tension in the interaction of the relationships of form, viewer, and context. The black leather jacket owes much of its status as a symbol to this image manipulation in connection with certain creative tensions associated with male identity: gay or straight, rugged protector or individualist survivor, hero or antihero, powerful or vulnerable, and tribal or mainstream fashion. (DeLong & Park, 2008: 171)

Kaiser, Nagasawa, and Hutton (1997) argue that all people experience ambivalence and that products produced in capitalist marketplaces (such as America and Europe) express ambivalence. The black leather jacket thus expressed the ambivalence of male identity. As the black leather jacket was worn by different male archetypical groups it created ambiguous meanings that needed to be negotiated within society. Successful negotiations of meaning rely on general consensus.

Dress scholars Marilyn DeLong and Juyeon Park (2008) noted that the black leather jacket was a symbol of military chic style in Germany during World War I, changed to total military power in World War II Germany, but perceived as brave when adopted by American military officers during World War II. The context of who was wearing, who was interpreting, and the historic timeframe contributed to interpreting the black leather jacket as different symbols. DeLong and Park further surmised that during the 1960s the black leather jacket became a symbol of teenage rebellion due to films where antiheroes adorned it, but in the 1970s became a symbol of a “cool” yet functioning member of society when the character of Fonzie wore it in the American television series Happy Days (1974–1984). Lastly, DeLong and Park argue that the black leather jacket shifted from “tribal” or subcultural fashion to mainstream fashion by the end of the 20th century when people from all levels of society adopted it.

Thus, the black leather jacket represents an example of symbolic interaction. Ambivalence of male identity created ambiguous meanings that needed to be clarified. Meanings were assigned to the jacket; meanings were based on social interaction; and interpreted given the situational context.

BOXED CASE 2.1: ONE INDIVIDUAL STARTS A TREND

Jayanada Nandini Devi was the wife of a civil servant in Bombay (today called Mumbai) and a prominent citizen in her own right. She is identified as the source of the “Nivi” style of sari draping originating in 1866 (Tu, 2009). Traditional saris are lengths of cloth that are unstitched and uncut, as dictated by Hindi custom. During Devi’s life, saris were draped around the body in different styles according to region, often with uncovered breasts. Given her status as a prominent person, Devi wanted something modest (to align with new ideas coming from colonialism) and something that was non-regional. She adopted a choli (a stitched bodice) and a skirt, with the sari draped over her left arm and shoulder (see Figure 2.7). The style was adopted by other women and was disseminated on a broader, national scale in the 1930s though the Hindi film industry (Dwyer & Patel, 2002). The style was free of regional identity and modest (e.g., the breasts were covered) and took on the meaning of a unified nation as well as a modern woman during the Indian national movement for independence (Tu, 2009). Today the Nivi style is prominent, has been worn by other leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, and is perceived by outsiders to be the traditional form of Indian dress.

Figure 2.7 The Nivi style of draping the sari around the body was created 1866 by Jayanda Nandini Devi. paffy/Shutterstock.com.

BOXED CASE 2.2: FASHION LEADERS: CELEBRITIES AND FASHION

Celebrities wield enormous power due to their elevated status, and are often viewed as authorities on different subjects. Celebrities have the ability to start a trend simply by wearing a garment, acting as a paid spokesperson, or, more recently, launching their own fashion brand. Jaclyn Smith (actress in Charlie’s Angels, 1976–1981) was one of the earliest celebrities to launch a fashion line with her collection of clothing for K-Mart in 1985. Other celebrities such as Russell Simmons, Jessica Simpson, and Beyonce have also found success in the fashion industry. Now, many are branching out into fragrances.

Celebrity fragrances had a brief life in the 1980s, most notably with Uninhibited from Cher, but today’s plethora of celebrity fragrances can be traced back to Jennifer Lopez’s Glow by J. Lo in 2002. In its first year it sold $200 million globally (Gordon, 2012) and since then the singer has launched over a dozen more fragrances. Her success is likely what influenced other celebrities to enter the fragrance market, such as Hilary Duff, Justin Beiber, Taylor Swift, Antonio Banderas, Lady Gaga, Jennifer Aniston, Halle Berry, Paris Hilton, Bruce Willis, Gwen Stefani, David Beckham, Tim McGraw, Britney Spears, Katy Perry, Jessica Simpson, Selena Gomez, Nicki Minaj, and Rhianna (see Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 Reb’l Fleur by singer Rihanna is just one of the many celebrity fragrances on the market. s_buckley/Shutterstock.com.

According to fragrance marketer Miranda Gordon (2012) celebrities are entering the fragrance market because it is lucrative. Compared to apparel lines, where you need different sizes, different fits, and different markets, fragrances have the one-size-fits-all ability to cross different markets. However, she says only a few are involved in the actual development of the fragrance.

The individual’s influence on fashion stems from choices one makes, one’s desire to be unique, and one’s role as a fashion leader. The desire to be different—to stand out from the crowd—motivates some people to wear aesthetic combinations that are unusual or peculiar. If the person is someone whom other people seek out for advice on fashion and clothing, that person’s choices can influence others’ style of dress. However, as people change their modes of dress, they prefer small changes rather than abrupt, big changes. This accounts for a linear or evolutional explanation for fashion change. Dressing at the individual level is about satisfying a personal need or desire. The desire may be to excite others, demonstrate a different understanding of aesthetics, or live out a secret fantasy. At the most personal, a person can change their body to achieve a unique appearance. But it is important to remember that dress is imbued with meaning that is negotiated with society.

•Adoption and diffusion model

•Aesthetic perception and learning

•Ambiguous

•Ambivalence

•Appearance management behaviors

•Body image

•Expressive qualities

•Fashion communicators

•Fashion innovators

•Formal qualities

•Historic continuity

•Public, Private, and Secret Self model

•Shifting erogenous zones

•Symbolic interaction

•Symbolic qualities

•Uniqueness

1.Using the Public, Private, and Secret Self model, identify examples of each cell that pertain to your dressing behaviors.

2.Identify a new fashion leader. This can be someone in class, school, community, or a celebrity. Discuss why this person is a fashion leader, what style the person endorses, and how you think s/he will influence fashion in the next three seasons. Now, identify a fashion leader whose influence has waned. What was this person noted for and why do you think his/her influence has fallen?

3.What celebrities have tried to influence fashion but did not succeed? Why do you think they failed where others have triumphed?

4.Do you think the theory of shifting erogenous zones is still relevant?

5.What ways have you alleviated boredom when you dressed?

1.Wear something unique and outlandish for a day. Visit different venues, such as school, a retail outlet, and a grocery store. How do people react to you? How do you feel wearing something that garners attention?

2.Bring in a celebrity fragrance to class. Discuss the scent and the flaçon (bottle) and packaging. How does it relate to that celebrity’s image?

3.You will need magazines or images from a specific past decade for this activity. Collect data on the length of shorts to chart a trend. You can collect data in one of two ways: (1) if the model is standing and you can see from the waist to foot, measure the distance from waist to foot, measure the distance from waist to hem of the shorts, and calculate a ratio; or (2) divide the leg into different areas, for example upper thigh, mid-thigh, just above the knee, and mid-calf. You and a friend will look at each image and determine to which category the image belongs. Keep a record of your data by year. Illustrate your results using a simple bar graph for each year. Based on your findings, predict how that trend will continue or recede. An alternative to this could be measuring the height of socks, using the following categories: below ankle, above ankle, mid-calf, and above calf/under knee.

4.Use Damhorst’s model depicted in Figure 2.2 to analyze a garment from your wardrobe.

__________________ Further reading __________________

Gibson, P. C. (2012). Fashion and the Celebrity Culture. Oxford: Berg.

Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (2009). Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers.

Knight, D., & Kim, E. Y. (2007). Japanese consumers’ need for uniqueness: Effects on brand perceptions and purchase intention. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 11 (2), 270–280.

Laver, J. (1969). Modesty in Dress: An Inquiry into the Fundamentals of Fashion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Mazzeo, T. J. (2010). The Secret of Chanel No. 5: The Intimate History of the World’s Most Famous Perfume. New York City: HarperCollins.

Studak, C. M., & Workman, J. E. (2004). Fashion groups, gender, and boredom proneness. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 28 (1), 66–74.

Tu, R. (2009). Dressing the nation: Indian cinema costume and the making of a national fashion, 1947–1957. In E. Paulicelli, and H. Clark, The Fabric of Cultures: Fashion, Identity, and Globalization (pp. 28–40). New York City: Routledge.