Society is based on the grouping of people together by some common trait, such as skin color, amount of money possessed, genealogy, or type of work performed. The role of society is for people with similar qualities or interests to support each other. In the European Middle Ages, feudalism was a type of society where people were categorized as land owners, merchants, and peasants. Similarly, in India the caste system divided people into four classes and in South Africa, under apartheid law, the population was separated based on racial laws. University society is divided into faculty, staff, administration, undergraduate and graduate strata and within each are further divisions (e.g., tenured, tenure-track, freshmen, sophomore, junior, senior, masters, doctoral). Each of these social strata developed their own rules of behavior and expectations. It is probably easy for you to recognize freshmen from doctoral students or people in different majors based on their habits and style of dressing. The unspoken but learned rules for people within the society are called habitus.

Habitus is a term coined by philosopher Pierre Bourdieu (1990) to explain learned behaviors that are taken for granted, but nonetheless indicate “appropriateness.” You may have never thought about why you eat with a fork, spoon, and knife. If someone were to eat with their hands or fingers you would probably think them uncivilized, but in the Middle East it is proper to eat with one’s hands. If you were to visit and began to eat with your left hand you would be considered barbaric because it is only acceptable to eat with your right hand (the left hand is considered unhygienic). Another example is removing shoes when entering a home. In many westernized homes guests retain their shoes when entering a house, because to remove one’s shoes without permission is considered rude. Yet, the opposite is true in many Eastern homes, where it is expected that guests remove shoes before entering the house, because shoes are considered dirty. Bourdieu argued that common acts like these become part of the structure of society and are deeply ingrained in the subconscious. A result of habitus is the development of aesthetic taste (Bourdieu, 1984).

Taste is a matter of aesthetic liking and appreciating. If you were invited to a reception at the White House or Buckingham Palace or the court of Japan, you would likely dress in a ball gown or tuxedo or formal kimono because you have learned that for formal occasions these dress forms are desired and necessary. While at the reception if you saw a guest dressed in jeans and a t-shirt, you might think, “that is bad taste.” Bourdieu (1984) believed that judgments of taste are in themselves judgments about social position. A judgment about good taste versus bad taste is in fact a judgment about social class—that is, the values and ways of one class are preferred over the values and ways of another class. He argued that children are taught appropriate taste for their class and to reject taste of other classes. The children then carry their leanings about taste into adulthood. Thus, when judging the informally-attired guest at the reception, you not only think the jeans and t-shirt are inappropriate but also indicative of an inferior social standing. Likewise, Figure 3.1 demonstrates a violation of good taste by wearing socks with sandals. For many people in America, wearing socks with sandals is considered tacky or classless. The man in the image perhaps never learned this rule or is from a society where wearing socks with sandals is socially appropriate.

Historian James Laver (1973) hypothesized that taste in fashion is related to its “in-ness.” He offered a guideline to demonstrate how fashions are perceived relative to the Zeitgeist (see Chapter 4, p. 80, for further explanation). When a style is 10 years too soon or “before its time” it is considered indecent; at five years too soon it is shameless; at one year too soon it is daring; the fashion “today” is “in fashion” or “smart.” That fashion one year later is dowdy; 10 years later is hideous; 20 years later is ridiculous; 30 years later is amusing; 50 years later is quaint; 70 years later is charming; 100 years later is romantic; and 150 years later is beautiful. These designations may also explain why some styles are revived from history (see “Historic resurrection” theory, Chapter 5, p. 107), because as time passes they are viewed with a different eye and could serve to be relevant again.

Also central to this chapter is the consumer demand model. This economic model posits that when prices are high there is little demand for the object being offered; however, as prices begin to decrease the demand increases. We can see this model in action when a new fashion collection is offered. Typically, new styles are higher in price than existing styles that have been available in the market for a while. As time passes, the price will fall (retailers want to sell them to make room for new stock) and more people will buy the style. This pattern continues until the price reaches its lowest-offered point and the style is sold out.

However, as economist Harvey Leibenstein (1950) articulated, there are some variations of this theory. He identified a Veblen effect, snob effect, and bandwagon effect, which contradict the classic consumer demand model. A Veblen effect is when more people purchase a product as the price increases. The snob effect is when preference for a product increases when the supply becomes limited. And the bandwagon effect is when preference for a product increases as more people adopt the product. These effects are influenced by personality traits of the consumer. Status consumption influences the Veblen effect, independence influences the snob effect, interdependence influences the bandwagon effect (Kastanakis & Balabanis, 2012).

In this chapter you will read about the influence of habitus and taste in fashion change. The theories that are discussed are reliant on judgments about “good” and “bad” and “appropriate” and “inappropriate.” The Trickle Down theory examines how lower classes copied the styles of upper classes, while the Trickle Up theory examines how upper classes copied the styles of the lower classes. In both cases, as strata of society copy others, they engage in the process of fashion change. Dress scholar Evelyn Brannon (2005) called trickle up, trickle down, and trickle across directional theories. She explains, “The directional theories of fashion change make prediction easier by pointing to the likely starting points for a fashion trend, the expected direction that trend will take, and how long the trend will last” (p. 82). Additionally, this chapter will also examine social and economic motivations for acquiring styles by presenting the concept of scarcity/rarity, consumption theories and political motivations for adornment.

The Trickle Down theory is a classic example of understanding how styles change. Conceived by sociologist George Simmel (1904), it is based on class structure and class difference. Sometimes you might hear it called “Imitation/Differentiation” or as anthropologist Grant McCracken (1988) called it, “chase and flight.” All three of these names give us a good idea of what this theory espouses. The Trickle Down theory suggests that fashions begin in the upper-most class. The class directly beneath the upper-most class observes what the upper-most class is wearing and copies them. This is then repeated by subsequently lower classes, until people in most classes are wearing the same fashion. At this point the upper class does not want to wear what the lower classes are wearing and thus changes style, prompting the entire sequence to begin anew. This is a reflection of what McCracken called social distance, or using clothing to display one’s social rank—and thereby social distance—from others. The imitation of the lower class by the upper class closes the social distance and the differentiation by the upper class re-establishes the social distance.

The Trickle Down theory is a classic understanding of fashion and was very relevant in societies that had strict class differences, such as Europe. In countries such as England, France, Germany, and Spain, people were divided into classes based on their heritage and pedigree during the Middle Ages. In general there were three classes: aristocracy, merchant, and working. Sometimes these could be split into further divisions, but in general kings and queens were at the apex, followed by nobles with titles such as prince, princess, duke, duchess, lord, lady, marquis, marchioness, baron, baroness, etc. The merchant class comprised business people who earned money and could be quite wealthy but did not have a title or noble pedigree. Nobles inherited wealth; merchants created wealth. The lowest level was the working class who worked as laborers or were peasants.

The king and queen of a land would wear a new style and it would be seen at court by the titled nobles. The titled nobles would copy what they saw, maybe because they liked the aesthetics or maybe because they wanted to curry favor from the king or queen and believed dressing like him or her would engender positive feelings, or maybe because they wanted to signal to others that they were in the same class as the king and queen. The merchants would then see what the titled nobles were wearing and copy what they saw, and would wear the style, which was then copied by their subordinates. By this time everyone in society was dressing like the king and queen, so they would have to alter their style in order to be different.

The Trickle Down theory explains the emergence of the three-piece suit. Its roots are traced to King Charles II of England in 1666. During this time in history the upper classes—especially the men—were very flamboyant in terms of their dress. Luxurious silks, laces, jewels, and fabrics made with gold and silver threads were not uncommon. It was a way to display one’s wealth (see Conspicuous consumption, this chapter). Charles II was the first king after the Interregnum1 and understood his situation was politically precarious; after all, his father King Charles I had been executed via beheading in a civil war between royal and Parliament rights and powers. To curb ostentatious display, he ordered his court to change their style of dress and offered a new outfit made of slacks, jacket, and vest “which he will never alter” (Pepys, 1972, p. 315). The phrase “never alter” references a standard suit immune from fashion trends. The fabric he chose was darkly-colored wool, and the cut of the suit was tailored. There was no ornamentation such as embroidery or gemstones; rather, the outfit was plain. He offered this as an option to reduce the appearance of excessive spending and encouraged his court to follow suit. He even wore it himself but eventually he and his court returned to their former ostentatious display of dress (Kuchta, 2007).

The idea of a somber, plain suit was picked up again by British Royalty during the Regency Period (1811–1820) when lush, expensive, flashy styles of dressing were eschewed for simplistic formality. Socialite and dandy Beau Brummel wore the simpler style, which was eventually adopted by others. Through the course of the next century, the suit was adopted as the basic and classic example of men’s attire. Edward, the Duke of Windsor (1894–1972), also helped to popularize variations of the suit when he wore suits made of gray flannel or in the Glen plaid check (later renamed Prince of Wales check). Suits were adopted by men in professional executive positions and men seeking employment. Today suits are found at all price points, in many different fabrications, for many different customers, be they upper class or working class, have vast amounts of money or are on a budget. (Musgrave, 2009).

Sometimes, a king would enact a sumptuary law. Sumptuary laws were restrictions on the use of certain fabrics, materials, or adornments, according to class. Sumptuary laws were enacted at the time that merchant classes began to obtain wealth and could afford luxuries that heretofore could only be afforded by the nobility. They were designed to prevent (the “wrong”) people from displaying wealth through clothing and are found in historical instances around the world. An ordinance from 1657 in the town of Nurnburg (today, Nuremberg, Germany) reads, “It is an unfortunately established fact that both men and women fold have, in utterly irresponsible manner, driven extravagance in dress and new style to such shameful and wanton extremes that the different classes are barely to be known apart” (Boehn, 1932–1935, III, 173). Sumptuary laws were found in Rome as early as 300 BC, in Colonial New England, Italy, Scotland, Spain, and England (Hunt, 1996). An interesting decree from 1669 Japan limits sumptuous costumes for puppets, except in the case of puppet generals (Shiveley, 1955).

Sumptuary laws were designed to control who could wear what status products. For example, Henry VIII enacted a sumptuary law in 1511 which restricted men’s apparel by rank (women were exempt from this law); silver cloth, gold cloth, sable fur, and wool were restricted to the rank of lord and above; velvet was limited to men of knight rank and higher and was further restricted to color—blue or crimson only to those who held the rank of knight of the garter or higher; the decree also limited the amount of fabric a servant man could use in his dress (2½ yards) (Hooper, 1915). Historian Milla Davenport (1976) noted that sumptuary laws were often ineffective, repealed, or unenforceable. Thus, sumptuary laws did not necessarily deter people from engaging in trickle down fashion.

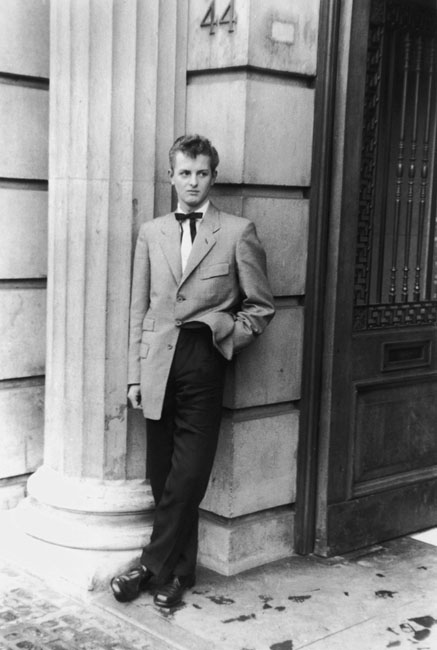

However, the Trickle Down theory did not only explain fashions in Medieval Europe. In the recent, modern era the story of the Teddy Boys is also the story of class differentiation and imitation. Beginning in 1950s London, the Teddy Boys were a group of working-class adolescents (see Figure 3.2). They worked jobs after school and had extra money in the pocket and chose to spend it on their appearance. They were inspired by, but did not adopt the exact dress of, the Edwardians.2 Edwardian style, named for the reign of King Edward VII (r. 1901–1910), had a revival among the upper class after World War II. The Teddy Boys of the 1950s wore a mix of British Edwardian style and American West style. From the original Edwardians they adopted drape jackets and slim “drainpipe” pants and from the American West they adopted vests and slim bowties. Their clothes, however, were generally made from luxury fabrications such as wool, brocade, and velvet which was incongruent with the occupations of working-class men. It was perceived as pretentious and socially rebellious. Additionally, the somewhat unsavory habits of the Teddy Boys got them labeled as gangs in the media. Consequently, the Edwardian style was no longer desired by the upper and middle classes in England who turned to other forms of dress.

Notions of class have often differed between Europe and the United States. In Europe class is based on pedigree and being born into a class, and often, one could not change one’s class. In the United States, class is based on money, not birth, and a person could change one’s class with financial success and learning social skills relevant to the aspired class. However, it appears that traditional notions of class have changed in both the United States and Britain. Since Margaret Thatcher’s election to the role of Prime Minister in 1979, the British class system started to change: “Money, which has not really featured in the British demarcation of social class, became very important. … As Thatcher was working to open things up and making the British class system more like America’s, the US class system started becoming more rigid” (Goldfarb, 2013, n.p.). Meanwhile, in the United States, the class system shifted from one of money to one of heritage. With regard to the Trickle Down theory of fashion this implies a shift who originates a trend today—those with money or those with pedigree?

The Trickle Down theory is about visually achieving status through clothing and appearance and the actual item that conveys status need not be expensive, just worn by the upper class. However, that item needs to be exclusive to the originating class at least for the time being (Brannon, 2005). Originally, the Trickle Down theory explained fashion change in Europe and America in the modern period until the middle of the 20th century, when social structure was based on class. McCracken (1988) observed that the social system is actually more layers than originally conceived by Simmel, and Kaiser (1990) noted today’s society has a hierarchy of layers conceived of demographics other than class/wealth: gender, race, age, and attractiveness. To this one could add fame, notoriety, sexual orientation, ethnicity, skin color/tone, and power. Additionally, fashion scholar Jennifer Craik (1994) argued, “Everyday fashion … does not simply ‘trickle down’ from the dictates of the self-proclaimed elite. At best, a particular mode may tap into everyday sensibilities and be popularised” (p. ix). Thus, the process today is more complex than simple “cut and paste” from higher to lower classes.

As the postmodern era began, the Trickle Down theory no longer adequately explained fashion change. Fashion styles were now originating from the common man as worn on the street. An alternative to the Trickle Down theory is the Trickle Up theory which explained this new phenomenon: fashions start in the lowest classes and are adopted by higher and higher classes until they reach the top class. This theory was proffered by scholar George Field (1970) and he called it “the status float phenomenon.” Anthropologist Ted Polhemus (1994) called it “bubble up.”

Fashion scholar Dorothy Behling (1985/1986) suggested that the direction of fashion—trickle up or trickle down—is determined by the median age of the population. She argued that role models will evolve from a population’s median age. When the median age is older, role models will likely be from upper classes and fashions will trickle down. However, when the median age is younger, role models will come from the lower classes, likely have little money, and therefore fashion will trickle up.

The A-shirt or singlet or tank top undershirt (sometimes disrespectfully referred to in the colloquial as “wifebeater”) is a white, sleeveless shirt usually made from ribbed, knit, cotton fabric. Its origins as an undershirt helped men remain dry when it was worn with dress shirts. However, working class men wore it without an outer shirt. Old School Hip Hop also adopted the shirt and helped to disseminate the style to a different market and designers like Calvin Klein offered luxe versions made from smooth cotton weaves in black. However, some people question the taste of wearing them. A recent examination of thread in an Internet chartroom asked the question: “Are ‘wife beaters’ low class?” The overwhelming majority of response was in the affirmative. One person wrote, “They remind me of some guy from a 40s movie who lives in a fleabag apartment, smokes a short cigar, and yes, smacks his wife” (GalileoSmith, 2010). Others complained about the appearance of underarm hair as a sign of their low class status. However, a minority of people who posted on the thread said they were permissible under specific conditions—if the underarm hair was shaven, the man wearing it was muscular, or if worn by toned, athletic women. Nonetheless, despite their working class origins, they have at times been fashionable regardless of the question of taste.

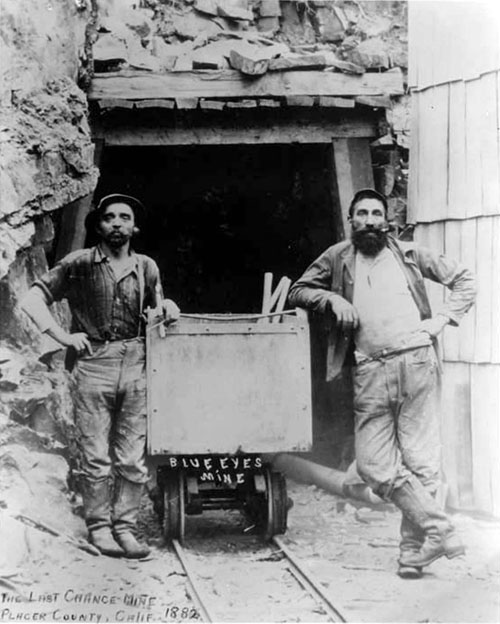

Like the origins of the fashionable A-shirt, jeans have a working-class pedigree as well. Levi Strauss was an immigrant who arrived in California in 1853 and opened a wholesale dry goods business in San Francisco. One of his clients was another immigrant, Jacob Davis, who found a way to improve workers’ pants durability by using copper rivets at the stress points. However, he did not have the financial capital to patent the idea so he explained this concept to Strauss and the two became partners. On May 20, 1873 they were granted a patent for “improvement in fastening pocket-openings” (Pacific Rural Press, June 28, 1873, p. 406). Strauss and Davis began to manufacture riveted work pants using denim imported from New Hampshire (Downey, 2009). The pants were originally known as “overalls” or “waist overalls” because they were designed as protective clothing to be worn over one’s regular clothing while working (see Figure 3.3). It was not until the early 20th century that their function transitioned to being worn as street clothing itself.

Jeans reached another market during World War II when factory workers wore them. The durability and strength of the pants were complimentary to the hard labor in machine shops and factories. But it was not until the 1950s that jeans started to gain popularity and were worn as a fashion statement. In the 1950s “teenagers” had become a new market when high school students who worked after school began to earn spending money. Teenagers were also rebellious against the status quo and turned to jeans as an alternative to the “proper attire” they were expected to wear. It also did not hurt that anti-hero actor James Dean wore jeans in the highly popular film Rebel Without A Cause (1955) as did other actors in similarly themed films, such as Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953) and Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda in the film Easy Rider (1969). Wearing them was considered inappropriate for the middle and upper classes because the originated from the working class. They were not refined like the woolen slacks that were common among middle class and upper class people. Plus, they had a bad reputation, given their association with subcultures that also adopted jeans, like Greasers and Hippies. They came to symbolize the anti-establishment.

In the mid-1970s heiress and designer Gloria Vanderbilt offered a line of fashionable and high quality women’s jeans. This brought the aforementioned “bad taste” jeans to a new market, but this time the garment was marketed as glamorous. Through the 1980s and 1990s the business of jeans increased dramatically and slowly made inroads into accepted fashion. Likely the advent of “Casual Fridays” (see Chapter 4) also helped society’s adoption of jeans and changed perceptions about them. By the end of the 20th century other designers were offering jeans in their collections and luxury houses such as Prada, Armani, and Dior were doing the same. Today, jeans are ubiquitous and are common staples of one’s wardrobe from people working in low-paying jobs in factories and on farms to high-paying executives of Fortune 500 companies.

Coco Chanel also looked to the working class for inspiration with her designs. More on Chanel’s design aesthetic is discussed in Chapter 4 but at least one of her iconic designs were appropriated from the dress of the working class. The little black dress was a modification of the shop girl, maid, or nun’s uniform, depending on your perspective and source of information. However, her creations were made with panache and she elevated them to fashion. Wilson (2003) notes that Chanel’s “[little] black dress and slight suit were the apotheosis of the shop girl’s uniform, or the stenographer’s garb” (p. 41). Chanel’s use of the working class for inspiration exemplifies the Trickle Up theory. Until Chanel, shop girls and secretaries were not considered fashionable. Fashion theorist Catherine Driscoll (2010) noted that Chanel’s “poor look” was akin to anti-fashion and disrupted the usual phenomenon of fashion originating from the upper classes. This time fashion rose from below.

The concept of scarcity or rarity is noteworthy in the fashion industry because for many people it is the elusive or unusual or different that they seek in their dress. Products in limited supply give their owners prestige and status because not everyone can own the product. That there is a dearth of products to be distributed to everyone means that those who can attain those products are “special,” because they have the resources or access to the items. Note how this relates to uniqueness as discussed in Chapter 2.

Some items are in limited supply due to nature. Many gemstones and precious metals are considered rare because they are difficult to find/mine or because only a small amount of them exist in the world. Platinum, gold, and silver have long been viewed as prestigious metals because of their relatively rare state. Gems such as emeralds, rubies, and sapphires are commonly known and can be found in most jewelry stores, but gemstones such as red diamonds, painite, green garnet, blue garnet, red beryl, and poudretteite are so rare that only a handful of each are known to exist.

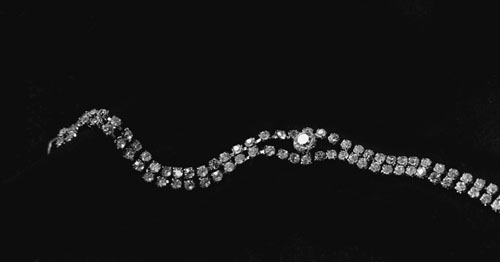

Other items are naturally abundant but their scarcity is manufactured by humans. Diamonds are such a case (see Figure 3.4). In nature, white diamonds are plentiful, but due to the monopolistic maneuverings of diamond conglomerate DeBeers, the company was able to control the supply of diamonds. They set prices, limited market availability and produced clever marketing campaigns to make consumers believe that ownership of a diamond was special because they were “rare” (Kanfer, 1993). The myth still persists today.

And still other items are manufactured purposefully in limited supply. Hermès Birkin bags have historically been in short supply. Not only did interested consumers need to spend upwards of US$10,000 for a basic model but they also were on a waiting list for years until their order was delivered. The combination of price and time meant that very few people could own the bag. Today the waiting list has been eliminated but the bag still retains its aurora of exclusivity. Other companies have followed this format and produce limited editions of popular products. Armani hired singer Rihanna to design lingerie for Emporio Armani in 2011, and TOMS and Nike manufacture limited edition shoes regularly. Likewise, Prada only produces a few of its runway pieces and disperses them to its retail outlets around the globe. At a 2011 trunk show for Prada in Honolulu, three men arrived wearing the same sparkly green shirt. When asked about their shirts, a customer replied that Prada only made 50 and “three of them are here in room now.” Whereas in many cases wearing the same item as another person would be social death, in this case the exclusivity and rarity of the sparkly green shirts signaled to “those in the know” the special status of the wearers.

Yet, businesses have violated the rule of exclusivity in order to increase profits and reach a larger market-share. The results had been near catastrophe for one, and the end of a lucrative business for another. For example, Gucci products were highly valued in the 1960s. The workmanship, design, and quality of leathers and hardware made Gucci handbags and shoes highly desirable. Owning a Gucci item indicated that the possessor was not only stylish but also affluent, for Gucci products were very expensive. Consumers would even deal with rude salespeople or inconvenient shopping hours to own a Gucci product (Forden, 2001). In the 1970s, due to a tangle of Gucci-family politics and business ventures, the company began selling inexpensive canvas bags printed with the iconic Gucci logo (Forden, 2001). These were eagerly bought by people who until then could only dream of owning something from Gucci. The unintended result was that the Gucci brand was devalued. Once anyone could own a Gucci item it made ownership less special. The customers who had always purchased expensive Gucci products stopped buying—why buy when anyone can? The Gucci executives eventually saw the error of their thinking, ceased production on the cheap canvas bags, and took measures to reclaim their status as luxury icon. Gucci violated the rule of exclusivity and rarity in diversifying its product mix to include cheap goods.

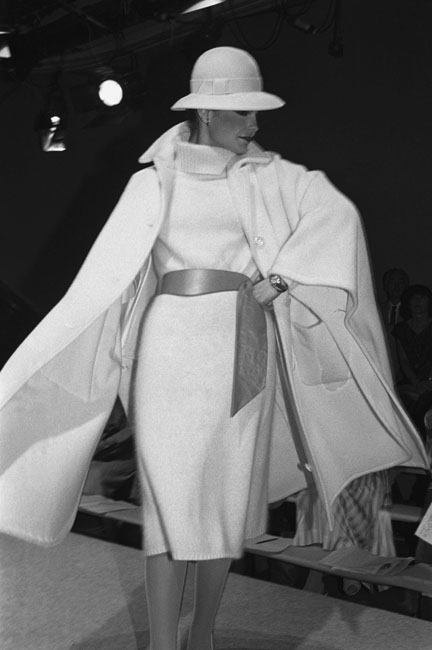

Another example of flawed business decision that did not take into account exclusivity or prestige of the brand was Halston (see Figure 3.5). Throughout the 1970s Halston was the auteur of chic American design. He designed matching separates in single colors and elegant gowns. A First Lady and numerous movie stars and socialites wore Halston designs. Jacqueline Kennedy wore his pill-box hats. Bianca Jagger, Liza Minelli, Barbara Walters, and Liz Taylor were just a few of his celebrity clients. He—and his creations—were regulars at the star-studded club of its time, Studio 54 in New York City, and it seemed everyone wanted to be draped in Halston. His line was carried by luxury retailer Bergdorf-Goodman. Then, in 1982 Halston sold his name to mid-range retailer J. C. Penney. Bergdorf-Goodman stopped carrying the Halston label because Halston designs could now be found at the mid-price-range American department store. Halston also licensed his name to fragrances, luggage, and carpets. The Halston brand had become overexposed and associated with the middle class. No one wanted to wear Halston anymore. The Halston name—once synonymous with glamour and wealth—was now synonymous with shopping malls and clearance sales. The aura of this exclusive fashion had disappeared. Roy Halston tried to revive his brand but passed away in 1990. Like the Gucci example, overexposure and mass diversifying of the brand resulted in a weaker consumer demand.

The theory of conspicuous consumption finds its origins in sociologist Thorstein Veblen’s A Theory of the Leisure Class (1899). He articulated that at the top of society were the leisure class, people whose inherited (or made) wealth afforded the luxury of a life of leisure. He articulated that this class of people visually conveys their status through purchases (or consumption) that were obvious (or conspicuous). With matters of dress, people adorned themselves with expensive apparel, accessories, and fragrances.

In order for this theory to “work” the products people purchase must be recognized as having some type of value, be it the cost, rarity, or the status associated with owning the product. We see this often in the purchasing of rare goods such as precious gems and metals or in the purchase of luxury branded products from Chanel, Prada, Dior, Christian Louboutin, Tom Ford, Armani, Hermès, Escada, Etro, Louis Vuitton, etc. (see Figure 3.6). Such purchases are often not necessary or functional (a white shirt is a white shirt) but by virtue of being branded by a luxury company increase their prestige (a white shirt from Gap sends a different message than a white shirt from Dolce & Gabbana). The meaning or symbolism of the product takes precedence over its actual function, though function is still relevant (Solomon & Rabolt, 2004).

A fetish is an object believed to have supernatural or mystical power. Examples of fetishes are often found in religion, such as Christianity’s holy water, the Voodoo’s doll, or Native American’s totems. Ethnologist John Ferguson McLennan (1896/1870) argued that this results in a relationship between people and material goods rather than people and their god. Psychologist Sigmund Freud (1995) extended the concept to sexual behavior and described a fetish as a substitution. Economist and philosopher Karl Marx used this concept to conceive a theory he called commodity fetishism. Very simply put, in a society where commodities are given perceived value, social relationships are based on the perceived value or cost of their commodities.

McCracken (1988) wrote that current consumer culture as we know it today owes much to the transformation in consumption to Elizabethan England (1558–1603), where the aristocracy engaged in conspicuous spending and consumption. He writes, “Elizabethan nobleman entertained one another, their subordinates, and, occasionally, their monarch at ruinous expense. A favorite device was the ante-supper. Guests sat down to this vast banquet only to have it removed, dispensed with, and replaced by a still more extravagant meal. Clothing was equally magnificent in character and expense” (p. 11). McCracken identified two reasons for this unprecedented and historic consumption of luxurious goods. First, it was a way for Elizabeth I to consolidate power by forcing her nobility to come to her to ask for resources. Second, the atmosphere at the Elizabethan court encouraged the nobility to compete with each other for the queen’s attention and her favor. By the 18th century, merchants were engaging in marketing, more goods were available for consumption, and the pace of fashion change had increased. By the 19th century, the development of the department store as a source for one-stop shopping also brought with it a type of entertainment through its visual merchandising and architectural design; it was also a fashionable place to see and be seen.

McCracken’s account of Elizabethan England’s consumption was not the first instance of conspicuous consumption. Evidence exists of conspicuous consumption in the ancient world. In an often repeated story, legend has it that Cleopatra and Mark Antony made a wager to see who could create the most expensive meal. Mark Antony’s menu no doubt dazzled Cleopatra, but her dish trumped his. At this time in Egyptian history, pearls were highly prized and very expensive. Cleopatra took a large pearl, dissolved it in a glass of wine, and drank it. Cleopatra won the wager. Evidence also exists of conspicuous consumption in ancient Rome where purple fabric was given status because of its relatively expensive and difficult procurement process. Divers had to explore dangerous waters to find the special mollusc whose ink was used as the dye base for the color purple. Finding enough molluscs was a costly process as many divers had to be employed. Wearing purple subsequently became synonymous with the upper class.

Conspicuous consumption has therefore existed for two millennia if not longer, but in recent decades, production time to produce goods has decreased dramatically. “From 1971, when Nike sold its first shoe, to 1989, the average lifespan of its shoe designs decreased from seven years to ten months. Constant innovation in shoe design compels customers to keep up with fashion and buy shoes more frequently” (Skoggard, 1998, p. 59). This means that new styles of a product are offered (and consumed) much more quickly today than in past decades, thus making recent styles “old” or “outdated” and in order for people to continually display their status they need to purchase products more frequently than before.

Yet, one need not be wealthy to engage in conspicuous consumption. The appearance of wealth can be created through the use of credit cards or spending exorbitantly in one area while neglecting others. In addition, many wealthy people are not necessarily engaging in conspicuous consumption today. Business theorists Thomas J. Stanley and William Danko (1996) examined consumption and income and divided people into two groups: under accumulators of wealth and prodigious accumulators of wealth. They found that prodigious accumulators (or wealthy people) are more likely to conserve money and live a frugal lifestyle. Conversely, under accumulators spend more money on status goods to create a façade of wealth.

There are two slight variations to the classic Conspicuous Consumption theory, status consumption and invidious consumption. Below, the differences are noted.

Conspicuous Consumption: purchasing products that obviously display status or wealth. For example, buying and using a Chanel purse to show (perceived) economic ability or resources to your friends, as described above.

Status Consumption: purchasing products that assist with group acceptance. Contrary to conspicuous consumption, these products may not necessarily be obvious but rather are used by people to fit into different social situations (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004, 34). For example, buying and using a Chanel purse to be accepted as “one of us” by a circle of friends.

Invidious Consumption: making purchases for the sake of invoking envy in others (Veblen, 1899). For example, buying a Chanel purse to make your friends jealous.

Conspicuous consumption is often perceived as vulgar, gaudy, and lacking taste. However, in the 1990s a new fashion for wearing simplified cuts and plain designs was noted (see Chapter 2, p. 38, “Aesthetic perception and learning”, an example of refined aesthetics in the 1990s). Fashion scholar Rebecca Arnold (2000)’s assessment of the new style was that it was “Inconspicuous consumption: wearing clothes whose very simplicity betrays their expense and cultural value, when quiet, restrained luxury is still revered as the ultimate symbol of both wealth and intelligence” (p. 169). Only a person “in the know” will know.

Because fashion is semiotic and can carry meaning, the dress of people can carry political overtones, especially when they are seeking to disrupt or change the status quo. In the United States red and blue colors carry political dimensions; red is aligned with the Republican party and blue with the Democratic party. Congressional senators and representatives often wear the color of their party during campaigns. As part of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), leader Mao Zedong outlawed silk and ornamentation, which he viewed as elitist and capitalistic, and instituted a unisex jacket and pants combination that became known as the Mao Suit. During the reign of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom (1837–1901), she decreed that Scottish men sew the side of their kilts to avoid any immodesty; many men, however, saw this as an attack on Scottish nationality and refused to do so as a political protest. During the Indian move for independence from the United Kingdom in the early 20th century, Mahatma Gandhi advocated for his supporters to adopt locally-made kahdi fabric rather than British fabrics.

There are political considerations about what nation’s clothing is worn. When John F. Kennedy was campaigning for the United States presidency in the 1960s, his wife, status icon Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, was criticized for wearing French designers. Since then, First Ladies and potential First Ladies have worn American designers and branded clothes, like Nancy Regan’s red Aldofo suits, or Michelle Obama’s choice of Jason Wu for inaugural gowns and J. Crew for daywear. Similarly, British Prime Minister Tony Blair abandoned Italian suits for British suits during his political career (Gaulme & Gaulme, 2012).

There are political considerations about where apparel is manufactured. Apparel made offshore tends to be cheaper but at a cost to manufacturing in jobs in the home country. For example, China has become one of the leaders of mass-produced manufacturing, with an industry built around cheap labor. However, some people view the outsourcing of labor from one country to another as problematic. The practices of some countries tend to raise concerns about sweatshops and unfair labor issues. Issues include forced labor, little pay, hazardous conditions, no overtime, long hours, and no breaks. This ethical issue has led to boycotts of clothing produced in foreign countries and “buy local” campaigns, but efforts may be undermined by shady regulations and practices. Saipan is an island in the Pacific Ocean where these types of conditions are found, but because it is a territory of the United States, clothing is labeled “Made in the USA,” misleading consumers trying to make ethically-sound purchases.

The two following examples illustrate how pants have had political connotations during two different historic occasions. During the French Revolution, the Sans Culottes distinctive dress style was associated with violence in the name of government reform. In the United States, the bloomer outfit became associated with women’s rights. Both fashions existed for a short, specific period of time and both demonstrate how clothing can be linked to political movements.

In the 1780s in France, fashion took on political overtones that threatened the health and safety (literally) of the ruling aristocracy. The fashionable mode at the time for those who could afford it was Rococo, a style known for its excess in everything from fabrics to jewelry. Those who were opposed to the royalist government looked to ancient Rome for inspiration. The classical Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) was viewed as the ideal form of government by the people for the people. The robe à la française, a sack gown featuring Watteau pleats at the back neck, and the robe à l’anglaise, an ensemble of fitted bodice and wide skirt, were the mode of the French royal court and its followers. But, opponents of the court wore loose neo-classical chemises of supple fabrics, inspired by Classical Rome.

A group of working class men, however, opted for a different mode of dress, one that was sartorially different from the ruling elite to express their political position. The style became known as the Sans Culottes and was adopted 1792–1794. The Sans Culottes were a political organization who advocated democratic rule and supported the left-wing government entities that ruled France during the Revolution via building barricades and providing support for violent attacks and massacres. Sans Culottes translates as “without culottes” and was originally a disparaging term that indicated the person was lower class. At the time the wealthy merchant class and aristocracy wore culottes (or breeches) usually made of expensive fabrics like silk. Sans Culottes, rather, wore pants. The Phrygian cap, also known as the liberty cap, was a red hat that was worn by slaves in Classical Rome and was adopted as symbolic headgear. In addition they sometimes wore the short-skirted coat known as the carmagnole and clogs. However, not all apparel items need to be worn together to be considered a Sans Culottes.

During the Terror, clothing of the middle class and aristocracy “served as evidence of guilt. Silk, lace, jewels, or any form of metal embroidery was a sign of the ancien régime, as were hair powder, wigs, or any elaborate form of coiffure. Even good grooming and cleanliness became suspect” (North, 2008, 190). Some people started to wear the Sans Culottes style as a means to avoid injury. The Terror ended with the Thermidorian Reaction when leaders of the Terror were executed. As a result the Sans Culottes no longer had government support and eventually disbanded.

The events that occurred in the 19th century Antebellum South (United States) related to changing the way women dressed and what they wore became collectively known as the Dress Reform Movement. In actuality it was a lot of small movements by different groups of people with different motivations for changing dress. Health and gender equality were frequently cited as reasons for reform. The weight of undergarments and the constricting nature of corsets were often cited as health issues. In the 1850s women were wearing as many as 12 layers of clothing (Fischer, 2001) which was putting a great strain on women’s waists and torsos. Corsets and tight-lacing reduced women’s waists to numbers in the teens (e.g., 13–19 inches) which resulted in internal organs being displaced and compacted. Pantaloons were also apparel garments cited for change. “Pantaloons dress reformers … wanted to reform female dress for comfortable fit, physical well-being, religious beliefs, women’s rights, or work opportunities—not to blur the distinction between the sexes” (2001, p. 83).

Fischer (2001) noted that it was first in 1827, in the utopian community of New Harmony, that “the connection between pantaloons and gender equality [had] been forged and would become the most important themes in dress to symbolize equality” (p. 38). Pantaloons did not become popular but resurfaced in 1848 in another utopian community, Oneida. However, they were seldom worn in private, mostly worn in public. Three years later in 1851 three women would wear them in public in Seneca Falls, New York: Elizabeth Smith Miller, Elizabeth Cody Stanton, and Amelia Jenks Bloomer.

What became known as “bloomers” and erroneously attributed to Amelia Jenks Bloomer’s creative imagination, was actually created by Elizabeth Smith Miller. Elizabeth Smith Miller designed a set of matching pants and short skirt (short for the time, mid-calf). Her friend Elizabeth Cody Stanton copied the design, as did Amelia Jenks Bloomer. Their new style of clothing was adopted by other dress reformers. Miller, Stanton, and Bloomer argued that the new style was healthier but did not link it to gender equality, because they realized that health was a stronger platform for change (Fischer, 2001). Nonetheless, bloomers were viewed as a fight for gender equality, while proponents saw them as a fight for men’s power. Women who wore bloomers, like Susan B. Antony, were ridiculed and harassed. The press did not help either and produced harsh commentaries and critiques about the women who wore them. Many who wore the garment were seen as trying to subvert men’s power. Around 1854 dress reformers started to discard the style, though Amelia Jenks Bloomer continued to wear them until 1858 (Fischer, 2001). Although the bloomer did not reach a national level, it nonetheless constitutes a fashion among a very specific group of people that had political motivations and overtones.

BOXED CASE 3.1: CINDERELLA’S GLASS SLIPPER

Have you ever wondered why Cinderella’s shoe was made of glass? Regardless of whether a glass slipper could actually be made, why was her footwear for the royal ball not made of decadent silk or sumptuous velvet? Why glass? Cultural historian Kathryn A. Hoffmann offers a convincing explanation for this meme. The following summation is based on a presentation Hoffmann gave at the “Cenerentola come Testo Culturale/Cinderalla as a Text of Culture” conference in Rome in November 2012.

Stories of a poor, destitute girl who meets her Prince Charming and lives happily ever after are found where the footwear varies from sandal to golden shoe to red velour mule, but it is Perrault’s version of “Cendrillon” with the glass slipper that most people recognize. Charles Perrault was a 17th century French author who penned some of the well-known versions of fairy tales still read today. It was Perrault who gave the heroine a slipper of glass.

In 17th century France, glass was a desired commodity and examples of ornate, decorative, and decadent glass products, from tables to mirrors to sculptures abounded in palaces and homes. The desire for imported glass from Venice even resulted in an outpouring of money from France, espionage related to the procurement of glass, and a few poisonings in which international plots were suspected. Sabine Melchior-Bonnet recounts some of that history in The Mirror: A History. Hoffmann argued that “Perrault’s glass slipper appeared in a line of fairy tales with glass elements and at the time of what can only be described as a French mania for glass.”

But the selection of glass as the material for Cinderella’s slipper was not arbitrary or based solely on the fashion of the moment. Rather, glass was featured in Italian and French fairy tales and was laden with sexuality and death: glass caskets, a glass tunnel, and fairy palaces of glass and crystal. Hoffmann noted, “Glass fits the patterns of both death (the forgotten girl among the cinders) and magical sexuality.”

Thus, we can interpret the glass slipper in a few ways. At the time of Perrault’s writing, glass was highly fashionable; therefore the glass slipper is the mode. Also at the time of Perrault’s writing, glass was expensive and linked to wealth and royalty; therefore the glass slipper is a sign of status. Also, prior fairy tales linked glass to sexuality; therefore the glass slipper represents femininity. Whatever your interpretation, this notion of a glass slipper has prevailed and been offered in different shoe iterations, including those made of Plexiglas, vinyl, or covered in rhinestones.

BOXED CASE 3.2: ETHICS FOCUS: THE DIAMOND MONOPOLY

Popular thought is that diamonds are rare. Their seemingly limited supply is one reason why they fetch high fees per carat. However, in actuality, diamonds are not scarce—they are made of carbon, one of the most plentiful elements on earth—and the myth of their rarity was created by diamond conglomerate DeBeers.

In the 1870s business man Cecil Rhodes began buying tracts of lands in present-day Kimberly, South Africa, on which diamonds had been discovered. Under Rhodes and later Ernst Oppenheimer, DeBeers (named after the owners of one of the land tracts) became the largest diamond company in the world and established a network that controlled price and flow of diamonds onto the markets. Their practices included quashing competition, buying competitive diamond mines to shut them down, stockpiling diamonds, and refusing to sell diamonds to people outside their network (Kanfer, 1993). Then, through a clever “diamonds are forever” advertising campaign, consumers began to view diamonds as heirlooms and rare, thus keeping them forever and not reselling them (Kanfer, 1993). The monopoly ended in the early 21st century when conflict diamonds (diamonds mined to support wars) became a moral issue and consumers started buying other gemstones. Nonetheless, DeBeers remains one of the largest and most profitable diamond suppliers in the world.

DeBeers’ practices, by restricting what diamond suppliers and designers and cutters can purchase diamonds, created an artificial scarcity. Because they marketed diamonds as valuable, keepsakes, and symbols of love and marriage, they created a desire among people for them. As a result, diamonds were used as conspicuous consumption. Their status as “rare” and expensive makes them a luxury item where size and quality were indicators of wealth and class. Consequently, consumers were (and still are) willing to pay enormous amounts for shiny bits of hardened carbon.

At the social level, fashion is influenced by habitus and taste that includes and excludes people based on their manner of dress. One of the first theories to explain fashion change, the Trickle Down theory was based on social structure; a number of theories since then have looked at fashion through the lens of society. When there was a paradigm shift in the mid-20th century, the direction of fashion influence reversed with styles originating in the street and working their way up through higher echelons of society. While other theories have also explained how trends move through social strata, the need to display one’s class (or assume the aesthetics of another’s class) is common among them all.

•Bandwagon effect

•Chase and flight

•Commodity fetishism

•Conspicuous consumption

•Fetish

•Habitus

•Imitation/differentiation

•Inconspicuous consumption

•Invidious consumption

•Snob effect

•Status consumption

•Taste

•Trickle down

•Trickle up

•Sumptuary Laws

•Veblen effect

1.If people like to possess exclusive or rare items why do not more brands offer limited edition products? What qualities make “limited edition” valuable?

2.Identify a product you bought where your motivation was to display (perceived) wealth, incite envy, or to fit in with a group of people.

3.List 5–10 items of the lower/working class that have become fashionable. List 5–10 that have not. Why do you think some became fashionable while others did not?

4.Simmel conceived the social system having upper class and lower class. Kaiser added gender, race, age and attractiveness as other strata of social organization. It was also suggested that fame, notoriety, sexual orientation, ethnicity, skin color/tone, and power are possible alternatives to social strata. Are there any forms of social organization that you would add?

1.Examine ads in fashion magazines and categorize them according to one of the three consumption theories discussed.

2.Show people an A-shirt and conduct a brief interview. Ask them to comment on it. Who wears it? Where do they wear it? Why do they wear it? Is it considered low class? Is it fashion? Organize their responses by theme. Do the themes tell you anything about taste? If the people you interviewed differ by age, is there a difference between older people and younger people?

3.Find a location where you can observe people, like a coffee shop or a bench in a park. As people walk by, analyze their mode of dress. How many scarce or rare items do you see? How many of these items are truly rare and how many are rare by human influence? Interpret your findings to relate to social organization.

____________________ Notes ____________________

1. The period in British History when England was ruled by Oliver Cromwell, after Charles I (Charles II’s father) was executed; 1649–1660.

2. Ted is a nickname for Edward.

__________________ Further reading __________________

Davis, F. (1989). Of blue jeans and maids’ uniforms: The drama of status ambivalences in clothing and fashion. Qualitative Sociology, 12 (4), 337–355.

Kanfer, S. (1993). The Last Empire: DeBeers, Diamonds, and the World. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Korotchenko, A., & Clarke, L. H. (2010). Russian immigrant women and the negotiation of social class and feminine identity through fashion. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 1 (2), pp. 181–202.

Morgado, M. (2003). From kitsch to chic: The transformation of Hawaiian shirt aesthetics. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 21 (2), 75–88.

Paulicelli, E. (2004). Fashion Under Fascism: Beyond the Black Shirt. Oxford: Berg.

Skoggard, I. (1989). Transnational commodity flows and the global phenomenon of the brand. In A. Brydon & S. Niessen (eds) Consuming Fashion: Adorning the Transnational Body (pp. 57–70.) Oxford: Berg.

Trigg, A. B. (2001). Veblen, Bourdieu and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Economic Issues, 35 (1), 99–115.