The western fashion system is a complex assortment of industries that work together and in tandem to produce, promote, and sell new products. Within the fashion system are forecasters, designers, manufacturers, marketers, merchandisers, sales representatives, managers, promoters, and retailers, each of whom has a role in fostering fashion change. What they decide to produce (or not produce), promote (or not promote) ultimately affects what may become fashion. It is necessary to understand that while businesses have a role in developing new styles, consumers have an equally important role in accepting new styles. Ultimately, consumers have to adopt the new style en masse for it to become a fashion.

The fashion industry is segmented into levels based on price point and relative quality. At the top of the list is haute couture. Haute couture is high-end, one-of-a-kind garments that are produced for a limited clientele. In haute couture the client will visit the designer who will take measurements or even construct a dress form to the exact measurements of the client’s body. The design will be handmade from the finest fabrics and once completed the pattern and muslins will be destroyed. True haute couture houses are members of La Chambre Syndicale de la Couture, a governing body for the industry. The cost of one garment can be in the thousands of Euros or United States dollars. One estimate is that there are approximately 2,000 haute couture clients in the world (Craik, 2009), but despite the small number of haute couture customers, it is a vital component of the industry because of the press it receives. Haute couture fashion shows are industry events that have become popular forms of entertainment. Celebrities with no or little connection to the fashion industry vie for seats to the shows. The shows are reported in popular consumer newspapers and magazines, as well as in industry periodicals such as Women’s Wear Daily. The shows are found online, posted in Facebook, tweeted on Twitter, and passed around on Instagram. A lot of buzz is generated from a small number of garments.

Designer categories follow haute couture and include well-known brands, such as Gucci, Prada, Marc Jacobs, and Dior. They use quality fabrics and are generally at the forefront of fashion. Many designer categories lead the industry in innovative designs or innovative use of new materials. Pieces can sell for US$1,000 or more. The designer category is followed by Bridge (price points generally under US$1,000), Better (price points under US$500), Moderate (price points under $100), and budget (price points under $50). These categories are generally made in factories, and as the price point descends, so too do the quality of fabrics and craftsmanship.

One of the most important components of producing and selling new products is making sure the intended audience is aware of the product, and more importantly, making sure the intended audience likes and wants your product. In marketing, there is a concept that posits that the more a person is exposed to something, the more familiar it becomes, and consequently the more it is liked. This is called the mere exposure hypothesis. In fashion, we can adopt this hypothesis to argue that the more a fashion style is seen by the public the more it will be liked (and subsequently purchased and worn). The fashion system uses this concept to promote new styles by showing them repeatedly in commercials, in magazine advertisements, product placements (such as at red carpet events), and visual display. The hope is that even if someone did not like the style upon initial viewing, by seeing it on television, in magazines, on celebrities, and in store displays, the viewer will eventually come to appreciate and purchase it. This is an overarching construct that you should remember as you read this chapter because the business of fashion is the business of repetition.

In this chapter you will read about theories and concepts that explain who controls the production of new styles; how new styles reach different markets; the role technology plays in fashion; how designers, merchandisers, and product developers get inspiration from the past; and how merchandisers create unique brand identities to differentiate their merchandise mix from competitors’ products.

As a designer, you may develop the most wonderful, most beautiful dress that anyone has ever seen. It is the perfect color, the right fabric, and looks great on all body types; but if a merchandiser does not manufacture it, or a buyer does not buy it, or a retailer does not promote and sell it, it will not become a fashion because not enough people will be exposed to it, know about it, and want to wear it. It will not reach what Gladwell (2002) called the tipping point (see Chapter 1, p. 18).

Market Infrastructure theory argues that only clothing sold in retail environments can become fashion. While a trend may start in an innocuous area, it takes the entire fashion complex to make the trend into a fashion. The reason is because the merchandisers and retailers make the style available to everyone. When the Mod look began in London, if retailers around the globe did not carry the style it would have never been available for other demographics to buy. They may have seen it on television or in magazines, but without the availability of retail stores the trend would have never become as large as it did.

The gatekeepers of fashion are the ones responsible for scouting and bringing new fashions to the masses. A gatekeeper is someone who holds power. At a dam, the gatekeeper is responsible for regulating the flow of water into a valley; when the water builds up behind the dam, the gatekeeper is responsible for releasing water into the river. Designers, merchandisers, buyers, and retailers are all gatekeepers of fashion. Their job is to control the flow and ebb of fashions. Designers are responsible for predicting trends and their job is to translate the trends into wearable garments. Sometimes they work independently and sell their designs to retail buyers and sometimes they may work for a company under the direction of a merchandiser. Merchandisers are responsible for researching a market, scouting sources for fabrics, trims, buttons, and manufacturers, and setting sales goals. Buyers are responsible for selecting garments that designers create to sell in a retail environment. Buyers have to know their customers’ demographics and psychographics in order to predict what their customers will want. Retailers are responsible for providing a space for the designs and promoting them through advertising and visual display. Each segment—designer, merchandiser, buyer, and retailer—has a role in selecting which styles are offered en masse to the public. They hold power as gatekeepers by analyzing trends and determining which trends they want to flow into the market. They also have the power to determine what should not be sold anymore. Based on the concept of planned obsolescence (as discussed in Chapter 1), that fashions are created to exist for only a short period of time, once a gatekeeper observes that the style has reached its maximum popularity, the gatekeepers discard it and bring in the next trend.

Gatekeepers must be keen to understand other aspects of fashion—the psychology, sociology, and culture of people—in order to design, select, and promote the trends. Simply featuring a garment in a store does not mean the style will become fashion. It must appeal to the customer on an aesthetic, psychological, sociological, and/or cultural level. You may be a fur designer and design the most luxurious lynx coat, it may have been bought and promoted through a retail store, but if the social climate of the area where the store is located is anti-fur, in all likelihood your design will not sell and will not become a fashion.

Trickle Across theory, also known as “mass market” or “simultaneous adoption,” posits that fashion trends reach all markets at the same time. Thus the dispersal of a trend is not according to class, as predicted by the trickle up and trickle down theories. Rather, the fashion system coordinates the release of the trend through various channels. This is made possible by mass communication, mass production, and the growing middle class (Brannon, 2005). Although Behling (1985/1986) argued that designs do not reach all market simultaneously but take at least a year, it is important to remember that she was writing in a time when the marketing and technology was not as sophisticated as today. For example, since then, fast fashion (see Chapter 1 for an explanation) has expanded the quickness that a trend can reach multiple markets.

How is it possible that a trend can start in multiple places at once? There are three parts to this answer. First, fashion forecasting. Some designers or merchandisers have in-house fashion forecasters and some utilize independent services outside their company. Fashion forecasters predict upcoming and future trends by conducting research; they observe known fashion innovators and leaders, look at trends in street fashion, follow past trends to predict a return (see “Historic Continuity theory”, Chapter 2, p. 45) and get a general idea for attitudes and responses to colors, fabrications, trims, and silhouettes. They then produce books and clients use these books when designing their upcoming lines or buying their stock. All levels of designers—from couture to budget—utilize some aspect of forecasting.

Second, many brands have different lines that reach different markets or price points. Ralph Lauren owns Polo, Chaps, Ralph Lauren Purple Label, Ralph Lauren Black Label, Ralph Lauren Sport, RLX, RRL, and Lauren. The Gap Company owns Banana Republic, Gap, Old Navy, Piperlime and Athleta. And the Burberry brands include Burberry Prorsum, Burberry London, Burberry Brit, Burberry Sport, Burberry Black, and Burberry Blue. Their goal is to reach as many different people via different markets as possible. When they forecast a new trend, they incorporate it into their different brands and lines by adjusting it for the particular customer. If bows are the trend, they might change the size, fabrication, or number used to reach the price point and consumer desire.

Third, knock-offs (or copies) can be produced quickly. Knock-offs began after World War II when discount manufacturers copied couture designs. While then there may have been a lag of weeks or months from copy to production, today a fashion can be knocked-off in days. Once a prominent fashion designer reveals a new line, scouts and competitors can digitally record the image, send it to their factories, and reproduce it at a different price point in a few days. This helps the trend reach more markets. More on knock-offs is discussed in the Ethics focus in this chapter.

According to Innovation theory technology has long provided the fashion industry with new trends and provides the foundation for many fashions. Technology is the creation of new products and new ways of creating new products. Technology provides the fashion industry with (1) quicker production, (2) affordability, (3) new products, and (4) increased availability. In this section we will examine some technological innovations and how they spawned or created fashions.

Faster production. The cotton gin was created in 1793 by inventor Eli Whitney. Prior to its invention, cotton was hand-picked. Hand-picked cotton had to be cleaned by hand to remove dirt, debris, and seeds. The cotton gin helped to reduce the amount of time it took to clean cotton. Cotton was placed in a box that had combs and when a handle was wound, the gears rotated, cleaning the cotton. Two centuries later, the jacquard loom was created in 1908 by Joseph M. Jacquard. This invention streamlined the production of fabrics made with motifs incorporated into the actual weaving structure of the fabric. This resulted in a change in the aesthetics style of fabrics available.

Affordability. Technology can also make products affordable. Genuine jewels and gem stones are expensive due to their natural or manufactured limited availability. When a desired product is in short supply, the price is typically high. Such is the case with diamonds, sapphires, rubies, emeralds, and pearls. This situation provided engineers with an opportunity to create imitation products.

Whereas genuine diamonds are expensive, scientists sought ways to provide similar options. Cubic zirconia was released on the market in 1976 as one alternative to diamonds. Cubic zirconia occurs naturally, though it is very rare, but can also be created by humans. Compared to diamonds, its similar appearance with flawless character and affordability made it a desirable substitute and major trend by the early 1980s. It can be made in any color, but pink cubic zirconia was especially popular in the 1980s as well. Scientists have since used new technology to improve the quality of cubic zirconia to make it harder and shinier. Today, other diamond substitutes like synthetic moissanite offer alternatives to diamonds while flawless lab-created emeralds, sapphires, and rubies are also available as substitutes to their natural counterparts. This technology provides people with the opportunity to have gemstones at an affordable price.

Increased availability. Mikimoto Kokichi revolutionized the pearl industry with his innovative methods to create perfectly spherical pearls. Perfectly spherical pearls are rare to find in nature as most natural pearls are uniquely or oddly shaped. In nature, a pearl grows when a foreign object—such as a grain of sand—finds its way into an oyster. This irritates the oyster which produces shiny nacre to cover it. The longer the irritant remains, the more nacre is added, and the larger the pearl. In 1916 Mikimoto and his partner Tokishi Nishiawa patented a method whereby an irritant is purposefully planted into the oyster to create a pearl. This means that pearls could be created at will and availability increased. By the 1920s cultured pearls had become fashionable in Japan, and when the Japanese market was flooded with pearls Mikimoto launched a marketing campaign at world fairs and exhibitions in the United States and Europe, expanding his global reach. Today, strands of pearls are classic items in a woman’s wardrobe (see Figure 5.1).

New products. Artificial fibers revolutionized the fashion industry. They were manufactured to mimic some of the properties of natural fibers (cotton, wool, silk, and flax) but improve on some of their weaker traits. For example, silk is soft and luxurious but wrinkles easily.

The first manufactured fiber was rayon and it was marketed as a substitute for expensive silk, due to similar soft handling and high sheen. It was made from naturally-occurring cellulose that was engineered into fibers. Early developments of rayon date to the mid–1850s but it was not until the early 1900s that rayon was made commercially, and the 1940s that it became common. Nylon was the first truly synthetic fiber, made entirely of chemicals. Engineered by Dupont in 1935, by 1940 nylon stockings had become a viable substitute for silk stockings when silk was in short supply during World War II.

Figure 5.1 The availability of cultured pearls, made possible by Mikimoto, helped to make them a classic wardrobe staple. Jewelry courtesy of Marcia Morgado; image by Attila Pohlmann.

Other artificial fibers have since been produced and marketed, with some becoming fashion statements. Spandex found favor with consumers due to its elasticity as foundation garments and today is used in high-compression fabrics. Polyester gained favor in the 1960s and 1970s for its wrinkle-resistance and comfort. And faux fur, made from a variety of artificial fibers, is used as an alternative to real fur.

The invention of spray-on-fabrics such as Fabrican provides the latest technological advancement in textiles. Using an aerosol can, fibers and polymers are sprayed directly onto a person and quickly dry. The fibers bond together (but not to the body), can be removed from the person as a complete article of dress, and can be washed. Currently available, it has yet to influence fashion greatly due to its high price, but given its versatility, ease of use, and uniqueness we will likely see spray-on-fabrics as fashion in the future.

While these examples demonstrate how technology has influenced fashion, historian Vesna Matković (2010) has argued that at times fashion has influenced technology. She cites the development of knitting machines to keep up with the fashions of the times. Beginning in Elizabethan England, William Lee produced a knitting machine in 1589 to meet the demand for fine-knit stockings. Stockings made by hand took time and manufacturing could not keep up with demand, but the innovation of a new machine using steel knitting needles facilitated faster production. Matković further recognized that new machines or alterations to existing machines were made to increase availability of open-work gloves (1793), lace knitwear (1769), ribbed knits (1758), single jacquard patterns (1769), vertical stripes (1776), and jacquard patterns in multiple colors (1921). Matković argued that fashion influenced knitting technology until the development of computer assisted design (CAD) technology:

It is difficult to say whether…fashion changes influenced the development of CAD/CAM technology or whether the development of a new generation of machines based on computer designing and computer production enabled them. This is a time when flat knitting machines could cover their greatest possibilities, i.e., they could knit everything that fashion required. (p. 137)

Bruce Oldfield, British fashion designer, has said fashion is “a gentle progression of revisited ideas.” Fashion designers often look to the past and use historic resurrection for inspiration when creating new garments. In Chapter 4 when reading about the Zeitgeist you learned about Dior and how he turned to the Belle Epoch to get inspiration for his collection that became known as the New Look. Though designers look to the past, they must reinterpret past aesthetics for the current era (see Figures 5.2 and 5.3). The fashions of the 1980s were a reinterpretation of the 1940s. In the 1980s women in the United States were entering the workforce in droves and sought garments that embodied power and respectability while still maintaining femininity. The last time that women in the United States had entered the workforce in such numbers was in the 1940s during World War II. In the 1940s, due to fabric restrictions, women’s garments were tailored. Suits with shoulder pads and tubular silhouettes with little frill and excess were common. These styles were reinterpreted for the 1980s: shoulder pads conveyed masculine authority, but peplums, vibrant colors, and supple fabrics such as rayon and silk conveyed femininity. In the late 2000s and early 2010s aspects of the 1980s returned. Torn, tight, acid-washed jeans were iconic during the 1980s and gave homage to the punk influence on fashion. They were paired with neon shirts. Wide belts also returned and chunky jewelry reminiscent of the large necklaces and earrings of the 1980s became popular again. In 2009 Ralph Lauren resurrected the 1930s for men. His collection sported suspendered slacks with “mended” tears and patches, reminiscent of real mends and patches that were necessary in the 1930s when much of the world was in a great depression. The difference, though, was in the 1930s the aesthetic was about clothing, while in 2009 it was about fashion. Today, with postmodernist pluralism influencing much of fashion, many prior trends have returned and are worn in unison: 1900s bell-shaped sleeves, 1930s backless dresses, 1940s high-waisted and wide-panted slacks, 1950s slim slacks and skinny ties, 1980s unstructured jackets with rolled sleeves and skinny ties (which in the 1980s was a homage to the 1950s), 1960s ethnic jewelry, 1970s skinny belts, 1970s peasant blouses, bellbottoms, and wedges, 1980s oversized silhouettes, ripped jeans and high waistlines, and so on.

Why does fashion history return? Some people like the memories and nostalgic feel. It may recall happy memories of their adolescence or foster the romanticized feeling of an era they are too young to remember but wish they knew. Also there are only so many ways a shirt or dress or slacks can be made or styled, so returning to the past is a good way to make something appear new, especially if it is for a new customer or market segment. Additionally, George Sproles (1985) argued that no truly new styles are created because “the human body has been decorated in every conceivable manner” (p. 62). Therefore, designers borrow from the past and reinterpret it for the current era. In addition, past fashions can be viewed as ironic (and reflect the postmodern climate) when something out-of-date is made fashionable again, such as the Nerd Chic look of the 2010s borrowing outdated fashions of the 1980s.

One reason why fashions from prior eras are revived and become popularized again is the role of nostalgia. Nostalgia is looking at past events or eras with a longing to return to them. Often, nostalgia invokes thinking of something in romantic or sentimental terms when times were easier. However, this glosses over the fact that often those sentimental “good old days” were rife with anxiety and their own issues. For example, the 1940s are viewed as a nostalgic time in American history when the nation banded together to fight the Japanese, German, and Italian armies. People think of the romance of Canteen dances, Rosie the Riveter, or the iconic kiss between a sailor and a woman in Times Square to celebrate the end of World War II. However, in reality, the 1940s were difficult. People were dying in war, money was tight, and food was scarce. These tend to be glossed over in nostalgia memories. Nonetheless, nostalgia tends to be a strong force in designing and acceptance of past fashions.

On a cattle ranch cows are branded using a disk of metal heated in a fire that is then burned into the cow’s hide and leaves a permanent impression burned into the skin. This is done so that the cattle rancher can identify his or her stock, and also so that others can identify it as well. A fashion brand is similar, where an image is metaphorically burned into the consumer’s mind. After World War II, there was an increase in ready-to-wear garments and manufacturers and designers needed a way to make their merchandise stand out from the crowd of other manufacturers and designers offering similar products. A black dress is a black dress is a black dress. They may be made by different people, use different fabrics and have a different style but in general they look the same, and in order for manufacturers to differentiate themselves they needed to create a brand. Like on a cattle ranch, the brand displays who you are as well as who you are not.2

Branding is not a theory but rather a concept that is important to the fashion industry. Fashion scholar Joseph Hancock (2009) wrote, “Branding is not just about individual products, but creates an identity for the company, for consumers, as well as for those who work within the organization. Branding creates a vision for the company” (p. 5). Branding allows companies to differentiate themselves from competitors of similar products. Clare McCardell was an American designer in the 1950s and 1960s who advocated for simple pieces that women could mix and match. She borrowed from or found inspiration from sportswear and made them into fashionable pieces. When Clare McCardell designed for the firm Townley, she created an A-line dress. Customers did not see the difference of this simple style and chose the cheaper competitor (Arnold, 2000). Brand recognition and brand value would have made the difference. Had Clare McCardell or Townley branded their merchandise, customers who value the brand would likely have purchased the more-expensive Clare McCardell design. Any basic or otherwise undistinguishable garment, that looks like everyone else’s, needs to be branded, as well as unique products that emphasize the brand’s aesthetic tastes.

Sometimes a company creates a backstory for a new brand to give it an identity. When the Abercrombie and Fitch company launched the upscale retail store Ruehl No. 925 in 2004, it manufactured a history for the company—that the Ruehl family immigrated to the United States from Germany during the middle of the 19th century and opened a leather goods shop at No. 925 Greenwich Street, Manhattan, New York City. The story continues that the company was expanded with two successive generations to sell clothing until sold to Abercrombie and Fitch in 2002 who continue the Ruehl family tradition. Even the logo—a bulldog named Trubble—was said to be a likeness of the original owner’s dog. This story is complete fiction, but it creates a brand image for the company, establishes a heritage (albeit false), and appeals to a segment of consumers who appreciate a rags-to-riches story. However, the retail concept did not do well and by 2010 all stores were closed. Nonetheless, Abercrombie and Fitch has used this method of creating a background story for its other retail concepts, including Gilly Hicks and Hollister Co.3

The concept of branding is important because it creates a connection between the product and the customer and differentiates one product from another. Customers become loyal to brands, which generates repeat-patronage. The image is created through advertising, promotional materials, visual display and customer’s experience with the brand that align to create a specific image. A shopping experience at Abercrombie and Fitch is different from a shopping experience at Prada. The Abercrombie and Fitch store is dimly lit, loud music is played, and promotional materials include larger-than-life black and white images of (mostly) nude models. The image they are selling is hyper sexuality. In addition, Abercrombie and Fitch employees are trained to be aloof and use slang (e.g., “later” for good bye) that is synonymous with the Southern California image the brand cultivates. Meanwhile, Prada is bright with plush carpeting and no music playing. Sales people wear black suits and black knit gloves. The gloves prevent soiling of garments or fingerprints on the glittering jewelry, but they also hint at the “museum quality” of the products. In addition, they encase customers’ receipts in an envelope made of stock-quality paper, which has been printed with their logo. Both Abercrombie and Fitch and Prada brands “speak” to different consumer markets and provide a specialized experience to the customers to make emotional connections with them.

According to fashion and clothing scholar Lou Taylor (2000) in the early 1990s established couture houses like Givenchy, Chloe and Dior began to re-brand and re-imagine themselves as youthful to court a newer, more lucrative market than their small number of couture customers. Marketing created the illusion of luxury. Image was paramount above all else. John Galliano made Dior into an opulent fantasy of exotic collections though extravagant fashion shows and clothing. Tom Ford made Gucci the image of jet-setting lifestyle by introducing new products (velvet slippers were one of the new products) and brushing the dust off classic handbag designs. Karl Lagerfeld made Chanel decadent and sensual by playing on established aesthetics of Chanel but exaggerating them.

One clever marketing technique of the brand is to extend the reputation of the name beyond the original products. A brand allows nearly everyone to partake in the world of luxurious goods thorough purchasing objects that are affordable. Nowhere is this truer than the luxury fragrance market. A Dior, Prada, Gucci, or Chanel ensemble may be out of range for most people, but their fragrances are comparatively a bargain. Grant McCracken (1988) calls this displaced meaning. By creating displaced meaning more people can partake in the brand lifestyle and in return businesses increase profits and market share.

One of the key elements of the brand is the logo. “The logo is essential to … success … Every franchised designer product bears this badge of status … which enables these goods to be sold far beyond their actual value” (Taylor, 2000, 137). The aesthetics of the logo provide instant recognition of not only the name but also what the name (or brand) signifies. Chanel’s interlocking Cs, Gucci’s interlocking Gs, and Louis Vuitton’s angled LV may appear simple, but they provide a powerful, instant brand recognition and stand for more than letters stamped on a product.

When Gap changed their logo in 2010 it was met with resistance and outcry from its consumers. The old logo of a blue box with the Gap spelled in capital letters was replaced with lowercase, Helvetica font; the blue box was reduced in size and its color graded. Public outcry was enormous. The new logo was likened to logos of pharmaceutical companies and IT companies and described as boring, bland, and incongruent with the Gap brand image. Less than one week after unveiling the new logo, it was eschewed for the former one. This example illustrates the loyalty, passion, and dedication to brand and brand logo (see Figure 5.4).

BOXED CASE 5.1: ETHICS FOCUS: KNOCK-OFFS

As a designer you spend your time and money researching a trend. You spend untold hours developing the pattern, readjusting, and perfecting it. You scour the markets for the perfect fabric and you agonize over selecting the right buttons. You manufacture it and market it and are proud when it is hailed in the press as triumph. Then one week later you see a copy of it in a retail store selling for a fraction of the cost you are selling the item for, and using a different brand label. Your design has been stolen; what do you do?

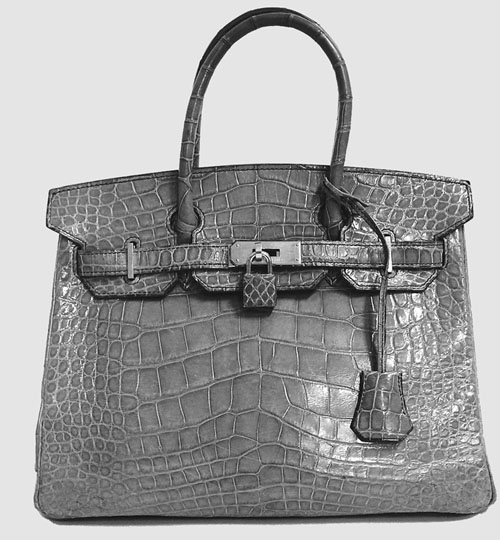

Knock-offs are copies of designs and should not be confused with counterfeits. Counterfeits, while also copies, are made to fool the customer into believing they are the genuine product. Counterfeits are illegal in most countries. However, knock-offs are made to resemble another design but are sold under a different label (see Figures 5.5 and 5.6). Knock-offs may or may not be illegal, depending on the country.

In Europe, you would have recourse if your original design was deemed unique. In Europe, fashion designs are protected for 25 years from being copied and copiers can be prosecuted. However, in the United States, fashion designs are not legally protected from being copied (note: prints and logos can be protected). A major component of the United States fashion system is the knock-off industry and some argue that (a) knock-offs help promote a trend, and (b) the economy would crash without knock-offs. However, designers argue that their hard work has been usurped and competitors are making money from their hard work. Lobbying groups such as the Council of Fashion Designers of America are arguing for legal protection and currently there is potential legislation in the United States that could protect unique designs for three years.

One designer, Rose (not her real name, she wished to remain anonymous for this publication), said she no longer produces mass quantities especially for this reason. Rose said that in the early 1990s she had a line of ladies’ casual clothing and one dress had a very distinctive design, both in pattern and in construction. She sold to retail stores and one day she went into one of the retail stores to find that her dress was no longer on the mannequins, but a copy of it was. Rose looked at the tag and saw that it was now made in Asia and under the store’s private label. She said she looked into taking the retailer to court but the costs would have outweighed the result. Today, Rose makes small quantities with limited distributions. She sells directly to the consumer and bypasses the retailer. Unfortunately, situations like this are not isolated.

Figure 5.5 Dominique Maitre/WWD © Condé Nast 2009.

Figure 5.6 The unique design of the Hermès Birkin bag (5.5) has spawned many knock-offs (5.6). Josephine Schiele/Lucky © Condé Nast.

BOXED CASE 5.2: NEW TECHNOLOGY OF BODY FASHIONS

A cyborg is a being with technological parts graphed or merged into its original body. They are widely featured in science-fiction literature, television shows, film, and animation, and for many years have been the idea of fancy. Yet, as body modifications are becoming more fashionable and technology is advancing, some people are becoming cyborgs. Products are being implanted onto and into the human body to improve its function, while at the same time also changing its aesthetics. Below are four novel ways that technology is changing people into cyborgs.

•Pierced eyeglasses: Earrings and body piercings are common, but James Sooy’s new design for eyewear is truly revolutionary. The lenses are attached to metal hinges that are then pierced to the bridge of the nose. No need for the eyeglass arms anymore.

•QR tattoos: The rectangular QR code is tattooed onto skin and when read by a smartphone’s QR code reader, it links to a website. The contents of the website can be changed as frequently as desired, so that the tattoo is continually “evolving” or “updated.”

•Magnetic fingers: Magnets are implanted into fingertips so they can easily pick up magnetized parts.

•Skin cellphones: Jim Mielke has created a touch screen that can be implanted under skin. The device uses a special type of dye so that when a person receives a call a digital image of the person calling appears on the skin. When the call ends, the image disappears from the skin. How does it run? Not on batteries; it runs on blood (thus making it environmentally friendly).

The fashion system plays a vital role in the life of fashion and trends. Decisions that designers, merchandisers, marketers, forecasters, and retailers make affect what becomes a trend and what does not become a trend. Some fashions exist because they were the only available styles in a marketplace and some styles become fashions because companies have made them available at different price points simultaneously to different markets. But the importance of technological innovation, branding, and history cannot be overlooked because they play a role in what can be produced and how it will be received or perceived by the public.

•Better

•Branding

•Bridge

•Budget

•Cyborg

•Designer

•Innovation theory

•La Chambre Syndicale de la Couture

•Displaced meaning

•Gatekeeper

•Haute couture

•Historic resurrection

•Market infrastructure theory

•Mere exposure hypothesis

•Moderate

•Nostalgia

•Trickle across theory

1.Why do fashion designers look to the past for inspiration? Why cannot they come up with something new?

2.What nostalgic trends do you observe in fashion now?

3.What technological innovation has impacted your aesthetic style?

4.Would you have a cellphone implanted in your arm?

5.What gatekeepers of fashion hold the most power?

1.Research a company with many different brands (e.g., Burberry). Find images or examples of the different lines and analyze what design features, marketing, and price points make them different from each other.

2.You will need access to an historic costume collection for this activity. Find examples of garments that used technology new at the time (e.g., a new fiber, a new way of construction, a new item like a zipper). Note how the invention made dressing easier, if at all. Discuss if this invention revolutionized fashion or was just briefly influential. Is it still being used today or has it changed with additional technological advances?

____________________ Notes ____________________

1. As noted in Chapter 1 there are many different fashion systems in the world. However, this chapter will focus on the western fashion system given the intended audience of this text.

2. The first widely recognized brand was Coca-Cola. Established in the 1880s, the marketing scheme encouraged people to ask for a Coca-Cola by name, rather than simply asking for a cola which at the time was common.

3. Gilly Hick’s fictional background is that she was young British woman who studied in Paris and moved to Sydney, Australia to open an underwear retail store in 1932. Hollister Co.’s fictional background is that John Hollister, Sr., moved from New York to purchase a rubber plantation in the Dutch East Indies before opening a store in 1922 in California.

__________________ Further reading __________________

Cline, E. L. (2012). Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion. New York City: Portfolio/Penguin.

Gomez-Aubert, C. (2011). New rules for old gems: Can El Salvador sustain and develop home grown design? Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, 9 (3), 288–307.

Leopold, E. (1992). The manufacture of the fashion system. In J. Ash and E. Wilson (eds) Chic Thrills: A Fashion Reader. London: Pandora.

McCracken, G. (1988). Culture and Consumption. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Miller, M. S. (2008/2009). Piracy in our backyard: A comparative analysis of the implications of fashion copyrighting in the United States for the International Copyright Community. Journal of International Media and Entertainment Law, 2, pp. 133–158.

Richardson, P. (2013). Tips for working in luxury sales. In K. Miller-Spillman, A. Reilly, and P. Hunt-Hurst, The Meanings of Dress 3rd edition (pp. 69–71). New York City: Fairchild Books.