Dr. Jung:

There were questions left over from the previous meeting, and as I have forgotten to bring them with me this time I will ask that they be put verbally now. Mrs. Keller, you had something, I believe.

Mrs. Keller: I would like to know something more about the ancestral image and the way it affects the life of the individual.

Dr. Jung: I am afraid I have not enough experience to elucidate such a question. My ideas on the subject are after all rather tentative, but I can give you an example of how the thing seems to me to work. Suppose a man to have had a normal development for some forty years or so, then he comes into a situation which awakens an ancestral complex. The complex will be awakened because the situation is one in which the individual is best adapted through this ancestral attitude. Let us say that this imaginary normal man we are talking about gets into a responsible position where he wields much power. He himself was never made to be a leader, but among his inherited units there is the figure of such a leader, or the possibility of it. That unit now takes possession of him, and from that time on he has a different character. God knows what has become of him, it is really as though he had lost himself and the ancestral unit had taken over and devoured him. His friends can’t make out what has happened to him, but there he is, a different person from what he was before. There may not even be a conflict developed within him, though that frequently comes; it may be that the image has just so much vitality that the ego recedes before it and yields to its domination.

Mrs. Keller: But if the image is demanded in order for him to fill that place, how can he come to peace with himself and at the same time conquer the image in case of conflict?

Dr. Jung: Well, in general the only thing to do is to attempt by analytical treatment to reconcile these images with the ego. If the person is weak, then the image takes possession. One sees this happening over and over again with girls when they marry. They may have been perfectly normal girls up to that time, and then up comes some role they feel called upon to play—the girl is no longer herself. The usual result is a neurosis. I recall the case of a mother with four children who complained that never had she had any important experiences in life. “What about your four children?” I asked her. “Oh,” she said, “they just happened to me.” One could almost say that her grandmother and not herself had had those children, and as a matter of fact, she did repudiate them.

Are there not more questions? Dr. Mann?

Dr. Mann: I handed in a question which I think will probably be answered in the further course of the lectures. I wanted to know if you would trace the progress of an irrational type from the superior to the inferior function as you traced it for us in the rational type through your own experience.

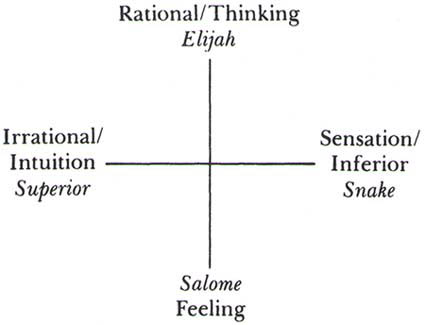

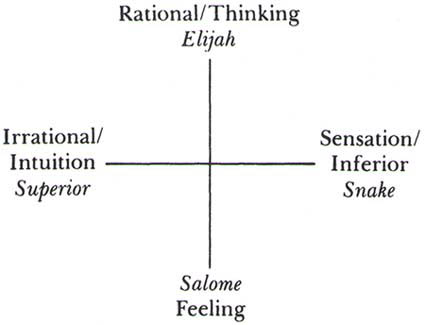

Dr. Jung: Take then an intuitive type whose auxiliary function is thinking, and suppose him to have reached the top of intuition and to have failed there. As you know, the intuitive is always rushing after new possibilities. Finally he gets himself, let us suppose, into a hole and can’t get out. There is nothing he so dreads as just this—he abominates permanent attachments and prisons, but here he is in a hole at last, and he sees no way that his intuition can get him out. There is a river passing, and railroad trains go by, but he is left just where he is—stuck. Now then perhaps he begins to think what could be done. When he takes up his intellectual function, he is likely to come into conflict with his feeling, for through his thinking he will seek devious ways out of his difficulty, a lie here, or some cheating there, which will not be acceptable to his feeling. He must then choose between his feeling and his intellect, and in making this choice he comes to a realization of the gap that exists between the two. He will get out of this conflict by discovering a new kingdom, namely that of sensation, and then for the first time reality takes on a new meaning for him. To an intuitive type who has not brought up his sensation, the world of the sensation type looks very like a lunar landscape—that is, empty and dead. He thinks the sensation type spends his life with corpses, but once he has taken up this inferior function in himself, he begins to enjoy the object as it really is and for its own sake instead of seeing it through an atmosphere of his projections.

People with an overdevelopment of intuition which leads them to scorn objective reality, and so finally to a conflict such as I have described above, have usually characteristic dreams. I once had as a patient a girl of the most extraordinary intuitive powers, and she had pushed the thing to such a point that her own body even was unreal to her. Once I asked her half jokingly if she had never noticed that she had a body, and she answered quite seriously that she had not—she bathed herself under a sheet! When she came to me she had ceased even to hear her steps when she walked—she was just floating through the world. Her first dream was that she was sitting on top of a balloon, not even in a balloon, if you please, but on top of one that was high up in the air, and she was leaning over peeping down at me. I had a gun and was shooting at the balloon which I finally brought down. Before she came to me she had been living in a house where she had been impressed with the charming girls. It was a brothel and she had been quite unaware of the fact. This shock brought her to analysis.

I cannot bring such a case down to a sense of reality through sensation directly, for to the intuitive, facts are mere air; so then, since thinking is her auxiliary function, I begin to reason with her in a very simple way till she becomes willing to strip from the fact the atmosphere she has projected upon it. Suppose I say to her, “Here is a green monkey.” Immediately she will say, “No, it is red.” Then I say, “A thousand people say this monkey is green, and if you make it red, it is only of your own imagination.” The next step is to get her to the point where her feeling and thinking conflict. An intuitive does with her feelings very much the same thing she does with her thoughts; that is, if she gets a negative intuition about a person, then the person seems all evil, and what he really is matters not at all. But little by little such a patient begins to ask what the object is like after all, and to have the desire to experience the object directly. Then she is able to give sensation its proper value, and she stops looking at the object from around a corner; in a word, she is ready to sacrifice her overpowering desire to master by intuition.

To a sensation type what I have said about the workings of the mind of an intuitive will doubtless seem utter nonsense, so different are the ways in which the two types see reality. I had once a patient who after about six months of analysis with me awoke with a sort of shock to the fact that I did not have large blue eyes. Another, having a still longer acquaintanceship with my study, which is painted green, asked me why I had changed it from the oak paneling that had been there all the time she had been coming to me. Only with the greatest difficulty could I persuade her that she it was who paneled the room in oak.

The same falsification of reality is the characteristic of all superior functions when they are pushed to the limit of development. The purer they become, the more do they try to force reality into a scheme. The world has all four functions in it—perhaps more, and it is not possible to keep in touch with it if one disregards one or more of the functions.

Miss Corrie’s question: “Will you please explain the relation of ambivalence to the pairs of opposites?”

Dr. Jung: If you take the pairs of opposites you are almost supposing two parties at war with one another—this is a dualistic conception. Ambivalence is a monistic conception; there the opposites do not appear as split apart, but as contrasting aspects of one and the same thing. Take for instance a man who has good and bad sides—such a man is ambivalent. We say about him that he is weak, that he is torn between God and the Devil—all the good is in God, all the bad in the Devil; and he is an atom swaying between the two, and you can never tell what he is going to do; his character has never established itself, but remains ambivalent. On the other hand, we can have a son who stands in between conflicting parents—nothing said of his character, he is the victim of these opposites; and so he can remain indefinitely. One had to invent the term “image” to meet this situation. Such a person can make no progress until he realizes that he has only stated half the case when he thinks himself victimized between the pairs of opposites, father and mother. He must know that he carries the images of the two within himself, and that within his own mind such a conflict is going on—in other words, that he is ambivalent. Until he comes to this realization, he can use the actual parents or their images as weapons with which to protect himself against meeting life. If he admits that the conflicting parties are parts of himself, he assumes responsibility for the problem they represent. In the same way I can see no sense in our blaming the war for things that have happened to us. Each of us carried within himself the elements that brought on the war.

The connection between ambivalence and the pairs of opposites is, then, a subjective standpoint.

Mr. Robertson: If the libido is conceived of as split always, where is the thing that gives the push in one direction or another?

Dr. Jung: The question of a push does not enter in, because libido, energy, is by hypothesis in movement. The expression “ambitendency” is a way of denominating the contradictory nature of energy. There is no potential without opposites, and therefore one has ambitendency. The substance of energy so to speak is a dissipation of energy, that is, one never observes energy save as having movement and in a direction. A mechanical process is theoretically reversible, but in nature energy always moves in one direction, that is, from a higher to a lower level. So in the libido it has also direction, and it can be said of any function that it has a purposive nature. Of course, the well-known prejudice against this viewpoint that has existed in biology has to do with the confusion of teleology with purpose. Teleology says there is an aim toward which everything is tending, but such an aim could not exist without presupposing a mind that is leading us to a definite goal, an untenable viewpoint for us. However, processes can show purposive character without having to do with a preconceived goal, and all biological processes are purposive. The essence of the nervous system is purposive since it acts like a central telegraph office for coordinating all parts of the body. All the suitable nervous reflexes are gathered in the brain. Coming back to the original point about the ambitendency, energy is not split in itself, it is the pairs of opposites and also undivided—in other words, it presents a paradox.

Mr. Robertson: It is not clear to me how you distinguish between teleological and purposeful.

Dr. Jung: There can be a purposive character to an action without the anticipation of a goal. This idea is fully developed in Bergson, as you know. I can very well go in a direction without having in mind the final goal. I can go toward a pole without having the idea of going to it. I use it for orientation but not for a goal. One speaks of the blindness of instinct, but nonetheless instinct is purposive. It works properly only under certain conditions, and as soon as it gets out of tune with these conditions it threatens the destruction of the species. The old war instinct of primitive man applied to modern nations, with their inventions of gassing, etc., becomes suicidal.

Mr. Robertson’s written question: “You have presented the two views that are held by the psychological types—the introvert looks at the top and the bottom of the waterfall, while the extravert looks at the water in between.

“But are not you yourself looking ‘at the top and bottom’ in formulating the idea above? Thus you have illustrated your own tendency (introvertive) to see enantiodromia. Or would you claim some objective validity to this particular concept?”

Dr. Jung: Certainly seeing the top and the bottom is an introverted attitude, but that is just the place the introvert fills. He has distance between himself and the object and so is sensitive to types—he can separate and discriminate. He does not want too many facts and ideas about. The extravert is always calling for facts and more facts. He usually has one great idea, a fat idea you might say, that will stand for a unity back of all these facts, but the introvert wants to split that very fat idea.

When it comes to a matter of objective validity, one can say that since so many people see this enantiodromia there must be truth in it, and since so many people see a continuous development, there must be truth in that too, but strictly speaking objective validity cannot be claimed, only subjective. Of course this is not very satisfactory, and the introvert is always having the tendency to say privately that his viewpoint is the only correct one, subjectively taken.

Dr. de Angulo: I don’t see the logical connection between introversion and the ability to see the phenomenon of enantiodromia. There must be millions of extraverts who see that too.

Dr. Jung: There is no logical connection, but I have observed it to be a temperamental difference between the two attitudes. Introverts want to see little things grow big and big things grow little. Extraverts like great things—they do not want to see good things going into worse, but always into better. An extravert hates to think of himself as containing a hellish opposite. Moreover, the introvert leans toward accepting enantiodromia easily, because such a concept robs the object of much power, while the extravert, having no desire to minimize the importance of the object, is willing to credit it with power.

Mr. Aldrich: It seems to me, Dr. Jung, that some of what you have said is in contradiction to what you say in Types about the extraverted nominalist holding facts discretely, and the introverted realist seeking always unity through abstraction.1

Dr. Jung: No, there is no contradiction there. The nominalist, though he has his emphasis on discrete facts, creates a sort of compensated unity by imagining an eternal Being who covers them all. The realist is wanting not so much to get to a unit idea as to get away from the facts to an abstraction of them in ideas. Goethe’s idea of the “Urpflanze”2 is an example of an idea that is too general, and illustrates what I mean by the tendency of extraverts to formulate “great ideas.” Agassiz,3 on the other hand, developed the notion that animal beings came from separate types, and this fits the introvert much better than Goethe’s conception. In a Platonist’s idea of life, there is always a limited number of primordial images, but still there are many, not just one—so the introvert has the tendency to be polytheistic.

Mr. Aldrich: But did not Plato ascribe the origin of the world to the mind of God?

Dr. Jung: Yes, he did, but all the interest in Plato is not on this conception, but on the conception of the eidola, or primordial abstract ideas.4

I told you last time5 about the dream concerning the killing of the hero and then the fantasy about Elijah and Salome.

Now the killing of the hero is not an indifferent fact, but one that involves typical consequences. Dissolving an image means that you become that image. Doing away with the concept of God means that you become that God. This is so because if you dissolve an image it is always consciously, and then the libido invested in the image goes into the unconscious. The stronger the image the more you are caught by it in the unconscious, so if you give up the hero in the conscious you are forced into the hero role by the unconscious.

I remember a case in point in this connection. This was a man who was able to give me a very excellent analysis of his situation. His mother had repeatedly told him, as he was growing up, that he would some day be a savior of mankind, and though he did not quite believe it, still it got him in a certain way, and he began to study and finally went to the university. There he broke down and went home. But a savior does not have to study chemistry, and moreover a savior is always misunderstood, and so nursed along in these ideas by his mother and by his own fantasy, he allowed himself to slump completely on his conscious side. He was content to take a position in an insurance company which amounted to little more than licking stamps. All the time he was playing the secret role of the despised of men. Finally he came to me. When I analyzed him I found this fantasy of the savior. He had understood it only intellectually, and so the emotional grip it had had on him remained unchanged—in spite of all he thought about it, he was still drawing satisfaction out of being an unrecognized savior.

It seemed as though the analysis would arouse him sufficiently, but even that did not sink in. He thought it was very interesting to live in such an odd fantasy. Then he began to do better in his work, and later applied for and won a directorship in a large factory. Here he collapsed utterly. He could not see that he had not realized the emotional value of the fantasy, and that it was the operation of these unrealized emotional values that had made him apply for a position he was in no way fitted to fill. His fantasy was really nothing but a power fantasy, and his desire to be a savior was based on a power motive. One can thus come to a realization of such a fantasy system, and yet have its activity persist in the unconscious.

The killing of the hero, then, means that one is made into a hero and something hero-like must happen.

Besides Elijah and Salome, there was a third factor in the fantasy I began to describe, and that is the huge black snake between them.6 The snake indicates the counterpart of the hero. Mythology is full of this relationship between the hero and the snake.7 A northern myth says the hero has eyes of a snake, and many myths show the hero being worshipped as a snake, having been transformed into it after death. This is perhaps from the primitive idea that the first animal that creeps out of the grave is the soul of the man who was buried.

The presence of the snake then says it will be again a hero myth. As to the meaning of the two figures, Salome is an anima figure, blind because, though connecting the conscious and the unconscious, she does not see the operation of the unconscious. Elijah is the personification of the cognitional element, Salome of the erotic. Elijah is the figure of the old prophet filled with wisdom.8 One could speak of these two figures as personifications of Logos and Eros very specifically shaped. This is practical for intellectual play, but as Logos and Eros are purely speculative terms, not scientific in any sense, but irrational, it is very much better to leave the figures as they are, namely as events, experiences.

As to the snake, what is its further significance?9

1Cf. CW 6, pars. 40ff.

2Cf. Goethe, Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären (1790).

3Louis Agassiz, Swiss-American natural scientist, who held a theory of “multiple creation.” Jung cited him nowhere else, though his library contains a copy of Agassiz’s Schòpfungsplan (1875).

4Cf., e.g., Timaeus 37d.

5Actually in Lecture 8, at n. 6.

62012: In Liber Novus, Jung wrote: “Apart from Elijah and Salome I found the serpent as a third principle. It is a stranger to both principles although it is associated with both. The serpent taught me the unconditional difference in essence between the two principles in me. If I look across from forethinking to pleasure, I first see the deterrent poisonous serpent. If I feel from pleasure across to forethinking, likewise I feel first the cold cruel serpent. The serpent is the earthly essence of man of which he is not conscious. Its character changes according to peoples and lands, since it is the mystery that flows to him from the nourishing earth-mother” (p. 247).

7Cf. MDR, p. 182/174, and CW 5, index, s.vv. hero; snake(s)—mostly as originally in Wandlungen und Symbole.

82012: In layer two of Liber Novus, Jung interpreted the figures of Elijah and Salome respectively in terms of forethinking and pleasure: “The powers of my depths are predetermination and pleasure. Predetermination or forethinking is Prometheus, who, without determined thoughts, brings the chaotic to form and definition, who digs the channels and holds the object before pleasure. Forethinking also comes before thought. But pleasure is the force that desires and destroys forms without form and definition. It loves the form in itself that it takes hold of, and destroys the forms that it does not take. The forethinker is a seer, but pleasure is blind. It does not foresee, but desires what it touches. Forethinking is not powerful in itself and therefore does not move. But pleasure is power, and therefore it moves” (p. 247). In later commentaries written probably sometime in the 1920s, Jung commented on this episode and noted: “This configuration is an image that forever recurs in the human spirit. The old man represents a spiritual principle that could be designated as Logos, and the maiden represents an unspiritual principle of feeling that could be called Eros” (p. 362).

9Cf. pp. 96 and 102.