CHAPTER THREE

THE LOSS OF ESSENCE

F ESSENCE IS WHO WE ARE, our true nature, then why is the majority of humanity not in touch with it at all? Why is it something we seek? To answer this question it is useful to observe young children and babies, from the perspective of essence. The many studies of children and babies made by psychologists in the past few decades have developed much useful knowledge. Of course, these studies have not been from the perspective of essence but from social, psychological, or physiological perspectives. They are usually conducted by researchers whose world views do not include essence. But now we need information about essence and young children. We can obtain this information by observing not only with our two eyes but with the subtle capacities of perception, the subtle organs of perception that can be aware of essence directly, without any inference. This is the only way essence can be observed and studied. Then we need to compare these observations with those of adults.

F ESSENCE IS WHO WE ARE, our true nature, then why is the majority of humanity not in touch with it at all? Why is it something we seek? To answer this question it is useful to observe young children and babies, from the perspective of essence. The many studies of children and babies made by psychologists in the past few decades have developed much useful knowledge. Of course, these studies have not been from the perspective of essence but from social, psychological, or physiological perspectives. They are usually conducted by researchers whose world views do not include essence. But now we need information about essence and young children. We can obtain this information by observing not only with our two eyes but with the subtle capacities of perception, the subtle organs of perception that can be aware of essence directly, without any inference. This is the only way essence can be observed and studied. Then we need to compare these observations with those of adults.

What we find when we observe in this way is that babies and very young children not only have essence, they are in touch with their essence; they are identified with their essence; they are the essence. The inner experience of a baby is mostly of the essence in its various qualities. This does not mean that the baby is conceptually aware of the existence of essence. The baby knows essence very well, and very intimately, but without mental involvement and without cognition. We know this from the experience of adults who discover their essence and remember knowing it, in some fashion, from their childhood. In other words, the baby knows essence but does not know that he knows. He is not awake to its presence and its nature.

The fact that human beings are born with essence has been known from ancient times. The baby is not only born with essence, but essence is the baby that is born. In describing essence, Gurdjieff says: “It must be understood that man consists of two parts: essence and personality. Essence in man is what is his own. Personality in man is what is ‘not his own.’ A small child has no personality as yet. He is what he really is. He is essence. His desires, tastes, likes, dislikes, express his being such as it is.”1

So we can conclude that people are born with essence but end up without it later on. Obviously, it is somehow lost, or the connection with it is lost. This does not mean that a baby experiences essence exactly the way an adult does. A baby does experience essence, but for the adult it will be more developed, more expanded, more distinct, more powerful, and it will function in ways that are only a potential in a baby. The baby's essence does not have the immensity, the depth, and the richness of the adult's experience of essence. It is generally lighter, in a sense, more diluted. The adult can experience his essence in such a light and fluffy mode, but it has more dimension and significance. Its capacities are more grown and developed. An adult also has the possibility of awakening to the presence of essence and its nature.

It would be interesting to observe the development of essence from babyhood to adulthood without interruption or loss. This would mean observing a person who does not lose his essence or the connection to it. But this possibility is so rare and unlikely that for all practical purposes it is nonexistent. We can, however, observe what happens to the human being's essence under normal circumstances, from babyhood to adulthood. What we see is a gradual loss of essence.

The fact of loss of essence also has been known from ancient times, at least by some. The human being is born with essence, but essence is lost after a while, and by adulthood the person is just vaguely aware of some lack or incompleteness. That is why the process of discovery and inner development is often seen as a process of return or remembering. Many teaching stories depict the loss and retrieval of essence. One such story, “Hymn of the Soul,” tells the sequence in beautiful and graphic detail:

When I was an infant child in a palace of my Father and resting in the wealth and luxury of my nurturers, out of the East, our native country, my parents provisioned me and sent me, and of the wealth of those their treasures they put together a load, both great and light, that I might carry it alone. . . .

And they armed me with adamant, which breaketh iron, and they took off from me the garment set with gems, spangled with gold, which they had made for me because they loved me, and the robe was yellow in hue, made for my stature.

And they made a covenant with me and inscribed it on mine understanding, that I should not forget it, and said: If thou go down into Egypt and bring back thence the one pearl which is there in the midst of the sea girt about by the devouring serpent, thou shalt again put on the garment set with gems and the robe whereupon it resteth and become with thy brother that is next unto us an heir in our kingdom.

And I came out of the East by a road difficult and fearful with two guides and I was untried in travelling by it. . . .

But when I entered into Egypt, the guides left me which had journeyed with me.

And I set forth by the quickest way to the serpent and by his hole I abode, watching for him to slumber and sleep that I might take my pearl from him. . . .

And I put on the raiment of the Egyptians, lest I should seem strange, as one that had come from without to recover the pearl; and lest they should awake the serpent against me.

But I know not by what occasion they learned that I was not of their country, and with guile they mingled for me a deceit and I tasted of their food, and I knew no more that I was a king's son and I became a servant unto their king.

And I forgot also the pearl, for which my fathers had sent me, and by means of the heaviness of their food I fell into a deep sleep.

But when this befell me, my fathers also were aware of it and grieved for me, and a proclamation was published in our kingdom, that all should meet at our doors.

And then the kings of Parthia and they that bare office and the great ones of the East made a resolve concerning me, that I should not be left in Egypt, and the princes wrote unto me signifying thus:

From thy Father the King of kings, and thy mother that ruleth the East, and thy brother that is second unto us; unto our son that is in Egypt, peace. Rise up and awake out of sleep and hearken unto the words of the letter and remember that thou art a son of kings; lo, thou has come under the yoke of bondage. Remember the pearl for which thou wast sent into Egypt. Remember thy garment spangled with gold and the glorious mantle which thou shouldest wear and wherewith thou shouldest deck thyself. Thy name is in the book of life, and with thy brother thou shalt be in our kingdom. . . .

The letter flew and lighted down by me and became all speech, and I at the voice of it and the feeling of it started up out of sleep and I took it up and kissed and read it.

And it was written concerning that which was recorded in my heart, and I remembered forthwith that I was a son of kings, and my freedom yearned after its kind.

I remembered also the pearl, for which I was sent down into Egypt, and I began with charms against the terrible serpent and I overcame him by naming the name of my Father upon him. . . .

And I caught away the pearl and turned back to bear it unto my fathers, and I stripped off the filthy garment and left it in their land, and directed my way forthwith to the light of my fatherland in the East.

And on the way I found my letter that had awakened me and it, like as it had taken a voice and raised me when I slept, so also guided me with the light that came from it.

For at times the royal garment of silk shone before my eyes and with its voice and its guidance it also encouraged me to speed and with love leading me and drawing me onward. . . .

And when I stretched forth and received it and adorned myself with the beauty of the colours thereof and in my royal robe excelling in beauty I arrayed myself wholly.

And when I had put it on, I was lifted up unto the place of peace and homage and I bowed my head and worshipped the brightness of the Father which had sent it unto me, for I had performed his commandments and he likewise that which he had promised.

And at the doors of his palace which was from the beginning I mingled among his nobles, and he rejoiced over me and received me with him into his palace, and all his servants do praise him with sweet voices. . . .2

However, this story and many like it look at the whole matter from a metaphysical or cosmological perspective, which explains what happens in general terms and gives a sense of the point of the whole thing. This particular story, for instance, answers the question of the “why” of the loss and retrieval of essence. Here we want to look at the loss from the phenomenological and psychological perspective, so that we can use the information to help us in the process of return or retrieval. If we understand how essence is lost, if we see it specifically and in detail, we will be able to see how to go back, how to retrace our steps, so to speak.

Essence is gradually lost or covered up (veiled from our perception) as the personality develops. We tend to identify more and more with the personality that develops in response to our environment. By the end we forget that we even had essence. We end with the experience that there is only our personality, and that we are that personality, as if it always had been thus.

This gives us the hint that in order to allow our essence to emerge again, we need to learn to disidentify from the personality and the sense of ego identity. This, in fact, is the main method that most systems of inner development employ. This disidentification, which can culminate in the experience technically termed ego death, is the main requirement necessary for the discovery of essence.

Now let's look at this process more closely and in more detail. It is true that essence is lost gradually as personality develops and grows. Our awareness of essence dims slowly over the span of a few years until there is no awareness of essence at all. This is looking at essence as one undifferentiated mass or whole, which is lost or becomes far away from our consciousness. This is true, generally speaking, but the picture looks different if we use better lenses and if we focus our inner microscopes more finely.

We see that a baby's essence has many qualities or aspects of essence, which we discussed in Chapter Two. A certain aspect dominates when the baby is resting, another when he is active, another when he is playful, and so on. There is an interplay, a dance, between the various aspects, depending on the situation, the activity, the time, and so on.

Not only does the baby experience a dance of many qualities and aspects, we observe that as the baby grows, different aspects of essence dominate in different periods of his development. The aspects of essence mostly manifested depend on the age of the baby or the particular developmental phase he is going through. The particular aspects of each phase or stage of development are organically interconnected with the processes of development specific to such stages. For instance, from two months to about a year the aspect of essence dominant has to do with a kind of melting sweet love and merging with the environment, especially with the mother. This coincides with the developmental phase that is termed the symbiotic stage by the ego psychologists, a stage when the baby is still unaware of differentiation between himself and his mother. Around seven months old, another more active, more outwardly expansive aspect, which has to do with essential strength, starts to dominate. After a while, the qualities of joy and will become dominant, as the toddler becomes more aware of his environment and starts exploring it with joy and a sense of power. Then the aspect of essential value assumes dominance for some time. In fact, we can see the stages of essential development in relation to the stages of the development of the ego.

The ego psychologists are aware of the development of strength, value, joy, and so on, but they are usually unaware that these are aspects of essence. They see them as emotional or affective experiences of the personality as it develops and attains a permanent structure. We will leave the subject of the specific and precise relationships between essential aspects and ego developmental stages to a future publication and will use here only the general idea of the relative dominance of particular aspects of essence during different stages of the development of the child.

Because essence has various aspects, and different aspects dominate at different times and have different functions, essence is lost aspect by aspect. It is true that essence as a whole is gradually lost as the personality develops, but we see within this overall process many specific processes, when various aspects of essence go through varying vicissitudes until they are finally lost. Each aspect has its own process and goes through its own vicissitudes, until it is finally buried. The total of all of these smaller processes make up the whole bigger process of the loss of essence. We observe that the aspect of love, for instance, goes through the vicissitudes of waxing and waning until it is finally dimmed and lost. And we see that this process is different from the processes that essential value, or will, or compassion, or emptiness go through. We see that certain aspects are lost before others. Some aspects are lost abruptly and some are lost gradually.

The point we want to make here, which no other system or tradition has emphasized, is that although essence as a whole goes through a process of dimming and eventual loss, specific essential aspects have different processes of development and varying vicissitudes. The environment affects essence as a whole, but it affects the different aspects differently. The aspect of the child's environment that finally shuts down the will might be different from the aspect that shuts down joy, for instance. This understanding of the loss of essence is of paramount importance when it comes to the question of techniques for retrieval of essence, as we will show in the next chapter.

Of course, ultimately, all aspects of essence must be veiled for some of them to be unconscious. If some aspects remain in the consciousness, they will tend to bring out other aspects spontaneously, except perhaps in instances of severe dissociation and splitting, which are the causes of severe mental pathologies. This is because essence has the characteristic of going deeper and opening whatever reality there is. If one aspect is present, without severe dissociation, it will naturally bring the rest of the aspects to consciousness.

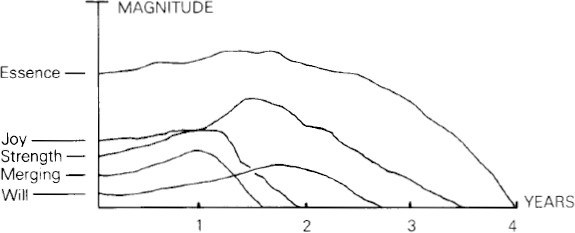

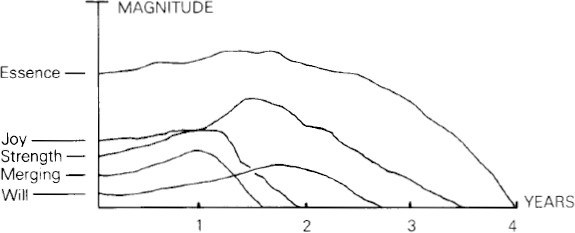

Figure 1. a) The loss of essence over time is compared to the loss of b) strength, c) will, and d) joy.

We can understand the relation of the overall process of loss to the various smaller processes of specific losses by using a graph. Let's look at just a few aspects, for illustrative purposes—say, those of merging, strength, will, and joy. The graphs in Figure 1 will illustrate their specific processes. The vertical line denotes magnitude or intensity; the horizontal line denotes time, in years. If we put all the curves together to get the general overall curve, which is the summation of the four of them, we will get the process of the essence as a whole, as shown in Figure 2.

This perspective is not simply academic. It has far-reaching implications for the formulation of methods of retrieval and return to essence. First, we can see right away that what one person needs to do to return to essence is not necessarily the same as for another individual. It is true that everyone loses essence, but the processes of that dimming and loss are different for each person. Different aspects are more deeply buried in one person than in another. Thus, other aspects are closer to the surface in one individual than those same aspects in another. Obviously, the methods for the return to essence should be flexible enough to accommodate these individual differences. The amount of work that an individual needs to do to free a certain aspect might be different from that needed by another individual. The methods needed and the attitudes emphasized to free a certain aspect will be different from those needed for the other aspects of essence. The heart of the matter here is the possibility of specificity, precision, and flexibility in our methods and techniques.

Figure 2. Here we see that the larger overall curve representing the vicissitudes of essence combines the various curves representing the different aspects. We need to remember that there are many other essential qualities not represented here, and that these curves vary from one individual to another; however, the variations will keep the general character of each curve.

We can look at the process of dimming and loss more closely, with better magnifying lenses. We have noted that essence is lost as the personality and its ego identity develop. We can understand this more specifically by looking at the vicissitudes of a specific essential aspect, as an example. Let's take the essential aspect of merging love. This aspect is present from the beginning of life but dominates especially between two and ten months of age. This period of life generally coincides with the period of ego development, called the symbiotic phase by Margaret Mahler:

From the second month on, dim awareness of the need-satisfying object marks the beginning of the phase in which the infant behaves and functions as though he and his mother were an omnipotent system—a dual unity within one common boundary. . . .

The term symbiosis in this context is a metaphor. Unlike the biological concept of symbiosis, it does not describe what actually happens in a mutually beneficial relationship between two separate individuals of different species. It describes that state of undifferentiation, of fusion with mother, in which the “I” is not yet differentiated from the “not-I” and in which inside and outside are only gradually coming to be seen as different.3

In this state of ego development, the child is not aware of the mother or himself as separate individuals in their own right. The ego has not separated out. Mother and self are still a unity—a dual unity. In infant observation, we find that when the infant experiences the dual unity without any frustration or conflict, his essential state is that of merging love. It is a pleasurable, sweet, melting kind of love. The baby is peaceful, happy, and contented.

However, as we have pointed out before, the baby is not aware of essence conceptually or from the perspective of an observer. He is the essence, so in this phase he experiences the dual unity of the symbiotic phase as the merging essence. What he is dimly aware of is the presence of mother and himself as “one,” and this “one” is felt as merging love. As Mahler says, there is still no differentiation between inside and outside, between self and mother. It is a dual unity, and this is his perception. However, he is actually experiencing the merging aspect of essence. The child does not know that he is the merging love. There is still no sense of a separate self in this phase. So there is the impression, right at the beginning of the ego's formation, that the dual unity is merging essence. This initial and primitive impression of the baby is faulty because the merging essence is he himself. But we see that this wrong impression lies at the root of the personality. This equation of the dual unity with the merging essence remains in the unconscious, at the root of the personality, for the rest of the individual's life.

This is a subtle point but of fundamental importance in understanding the relation of the personality to essence. Whenever there is any loss of the symbiotic union, the dual unity with mother, the child experiences the loss of the merging essence. To repeat, this is because for him the merging love aspect of essence is he and his mother together. That is what he is aware of when there is merging love. He is not introspective, so he is not aware of the presence of this aspect of essence from an observer's point of view. He is enjoying the merging love but sees it as the undifferentiated union with mother. In his mind there develops, at the primitive level of his ego, the association of loving proximity with the mother to the merging love of essence.

Whenever this proximity, this symbiotic unity, is not there, the merging love of essence disappears. This satisfying symbiotic unity can be lost for many reasons: rejection by the mother, distance from her, frustration by her, too much clinging from her side, physical or emotional abandonment, actual loss, to mention a few.

This always happens because there is no perfect symbiotic relationship between mother and infant because of many factors, mostly unavoidable. However, the loss can occur in many different ways, some more painful than others, some sooner than others, some more abruptly than others, and so on. It would take us far away from our objective to go into the details here. We only need to know here that merging essence is at some point lost.

The baby experiences simultaneously the loss of the essential aspect of merging love and loss of the positive gratifying symbiotic relationship with the mother. He feels he lost the merging love, but he believes he lost the dual unity. He starts feeling incomplete because he lost an essential part of him, his merging love. He knows this only dimly, only subconsciously, so to speak. But what he observes is the loss of the gratifying symbiotic relationship with the mother, so naturally he assumes that his feeling of incompleteness is the result of the loss of this relationship. He in fact believes subconsciously, and in time unconsciously, that the part of him that is lost is the mother. This can happen easily because in the symbiotic phase there is no differentiation yet between self and mother. As he starts to differentiate, and the mother becomes more of a separate person, he can only think that what he lost is his mother.

There is another subtle point in the symbiotic phase. The baby feels something has left him, and he sees the “good mother” as what has left him. In the symbiotic phase, he cannot have the conception that he lost something, because “he” as a separate person does not exist yet, not in his mind. So later on, when the individual contemplates the loss of merging essence, he can only think of it as loss of the “good mother.” This is because he is now a separate individual and cannot function or operate as a dual unity, at least not consciously. In his deepest unconscious, the loss of merging essence is equated with the loss of the dual unity. (He cannot be conscious of this or he will lose his sense of being a separate individual.)

When merging love is lost, there is left in its place a vacuum, an emptiness, a hole in the being. Merging love of essence is a fullness—something is there. It is a delicate, soft fullness, a substantial presence. So its loss leaves an experience of an absence, a lack, that is acutely and painfully felt by the child. When an adult feels this emptiness or hole, it is usually experienced as an incompleteness, a lack, a deep deficiency.

This deficient emptiness is too painful for the child to endure. It is felt both emotionally and physically as painful. It is also experienced as a threat to the newly forming structure of the ego. This structure is still too weak and fragile to tolerate such loss, which happens right at the beginning stages of ego formation. The ego still needs the experience of gratifying symbiotic union for its wavering and fragile cohesion. To let itself feel fully the experience of loss of the merging essence, which is to the child's mind the complete loss of the “good mother,” will be too shattering. The child still experiences the need for the “good mother” for his very survival, both physical and psychological, so really feeling the loss will bring in a great anxiety: the fear of total annihilation and dissolution.

Thus, the child learns not to feel the loss and the consequent emptiness. He learns to fill the emptiness, to cover it up, to bury it. He not only relegates it to the unconscious, he actually fills it with all kinds of emotions, beliefs, dreams, and fantasies.

There are two main ways a child can fill this hole, the absence of the merging essence. He either denies its existence completely and fantasizes the presence of the absent quality (here seen as the presence of the gratifying symbiotic union with mother), or he adopts attitudes, traits, mannerisms, dreams, and fantasies that are designed to regain the lost part. These are really attempts to regain the gratifying symbiotic unity with the mother. In the first case, he manufactures a false quality; in the second, he tries to get the merging by developing certain parts of his personality. Usually a child combines both strategies in differing proportions.

These attempts are designed to fill the hole, the lack resulting from the loss of the merging essence. The filler is nothing but parts of the personality. It is what the ego psychologists call self-representations. Edith Jacobson, one of the leading theoreticians in ego psychology, defines self-representation this way:

From the ever-increasing memory traces of pleasurable and unpleasurable instinctual, emotional, ideational, and functional experiences, and of perception with which they become associated, images of the love objects as well as those of the bodily and psychic self emerge. Vague and variable at first, they gradually expand and develop into consistent and more or less realistic endopsychic representations of the object world and of the self.4

We are not saying that all self-representations that make up the ego identity are attempts to fill this hole; some of the self-representations do not perform this function. But we are saying that what fills the hole becomes part of the self-representations. In fact, we assert that they form the most vital self-representations. Ego psychologists and object relations theorists do not say anything about holes or filling holes. They are not aware of the essence or of its loss. They do understand that the ego and its identity (self) are formed by the organization of self-representations.

“Shafer (1976), in his concern for a more precise use of the terms self and identity, writes: ‘Self and identity serve as the superordinate terms for the self-representations that the child sorts out (separates, individuates) from its initially undifferentiated subjective experience of the mother-infant matrix.’”5

Here we are accepting completely this understanding of the development of the personality. We do not contradict any part of the object relations theory of the development of the personality. We are only adding the understanding that the main islands of self-representations, besides forming the sense of identity, function to fill the holes of essential losses. We have discussed so far the loss of merging love only. The loss of other aspects of essence leaves other holes and deficiencies.

Almost every human being fills the hole of merging love with certain sectors of the personality. Everybody loses the merging love aspect of essence through loss or frustration of the symbiotic union with the mothering person. Everybody is left with a hole. Everybody fills the hole by developing parts of the personality, either by false merging or attempts at getting their merged state. Variations will all be on the same theme.

We can see that the merging love issue is one of the main unconscious determinants motivating adults toward intimate love relationships and is also the reason behind many of the difficulties in relationships. It is well known in depth psychology that people see their mothers in their love partners. This happens, of course, because individuals deeply feel and believe that their incompleteness will be eliminated and their longing will be satisfied by regaining the gratifying merged relationship with the mother, now displaced to a person of the opposite sex. This is probably the origin of the idea that a partner of the opposite sex is our “second half,” or our complement.

What the person really wants and misses is part of his essence, the merging love, and is not the love partner or the relation with him or her. The individual believes that what is missing is the other half, or the intimate relationship, because that is what the child was able to see at the time of the original loss. The adult, like the child, does not know consciously that what is missing is part of oneself. So the search for fulfillment is directed outward, although the only thing that will actually work is the retrieval of the lost aspect of essence, the merging love. Therefore, intimate couple relationships will not be completely satisfying if the person is not able to experience this aspect of essence. The partner or the relationship cannot be but a poor substitute for the merging essence. And the partner will usually be blamed for the frustration, although the frustration doesn't have much to do with the partner. We are not condemning intimate love relationships or the desire for them; we are attempting to provide an understanding of one of their dynamics, a dynamic that usually causes great confusion and conflict about such relationships if not understood and resolved.

We have shown how a segment of the personality is developed as an aspect if essence is lost. It is possible to follow the vicissitudes of each essential aspect and see exactly the specific childhood situations that universally cause its loss. We will see that as each aspect of essence is lost, a certain hole or deficient emptiness is created. This is then filled by the development of a certain sector of the personality, a part of the personality determined by the particular aspect of essence lost, and by the specific childhood situation or situations that led to its loss.

In time, there will be no essence in the person's conscious experience. Instead of essence or being, there will be many holes: all kinds of deep deficiencies and lacks. However, the person will not usually be consciously aware of his perforated state. Instead, he is usually aware of the filling that covers up the awareness of these deficiencies, what he takes to be his personality. That is why this personality is considered a false personality by people aware of essence. The individual, however, honestly believes that what he is aware of is himself, not knowing that it is only a filling, layers of veils over the original experiences of loss. What is usually left of the experience of essence and its loss is a vague feeling of incompleteness, a gnawing sense of lack, that increases and deepens with age. However, this is true only for what is called the normal person, the adjusted personality, the standard of psychological balance in the culture.

But for many others, whose attempts at developing a personality were not as successful, where difficulties in childhood were too painful to make this personality work, the sense of deficiency and incompleteness is much more acute, much more painful, and much more incapacitating.

This state of taking the personality as the true identity and master of our life is what the Sufis call the state of sleep. The Sufi master Sanai of Afghanistan puts it this way: “Humanity is asleep, concerned only with what is useless, living in a wrong world.”6

The essence is gone, and the personality claims its position. The shell claims to be the essence. The lie claims to be the truth. No wonder man is said to be living upside down. This situation is illustrated in graphic detail by a Sufi story that tells how the servants of a large house take it over when the master leaves for a long period. In time they forget that they are the servants; they forget their true positions and function. Eventually, they even believe they own the house.7

It is not possible for the average person who is identified with his personality to understand or appreciate the significance and the far-reaching consequences of this subversion. The average person actually, albeit mistakenly, believes that his personality is he himself. He has no context for comparing the experience of his personality with what he lost. He can only compare the experiences of his personality. The beauty and the wonder of essence is completely lost to him.

Repressing the various holes and the painful emotions around the losses necessitate that essence in its various aspects be repressed and cut off completely and efficiently. For if essence emerges into consciousness, it will ultimately bring to consciousness the deficiencies and the painful memories around it.

The human organism has in it many capacities for perception. The physical senses are the capacities available to ordinary humanity. However, there are many other organs or capacities for perception that are subtle and in a sense invisible. There are capacities for inner seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, and so on that have to do with the perception of the inner realm, that of the essence. There are capacities for intuition, direct cognition, synthesis, discrimination, and so on. All of these capacities are fueled by the substance of essence. Essence is what animates them. It is their life and light. This is what is hinted at in the Quranic light verse: “Allah is the light of heaven and earth. His light is like a lamp within a colored niche. The lamp is within a crystal, which is like a pearly heavenly body. It is lit from a blessed olive tree, not of the East or the West, whose oil itself nearly shines, without it being touched by any fire. Light upon light” (author's translation).

The organs of perception are, in fact, parts of essence; they are its organs and capacities. So when essence is cut off, the fuel of these capacities is gone, their light is dimmed, and most often goes out. The person loses not only his essence, but also his various subtle capacities and organs of perception and inner action.

These organs or capacities are connected to various energetic centers in the body that animate both the body and the mind. There are many and various centers as we discussed in Chapter Two, operating at different depths of the organism. There is the level of the chakras, which are centers connected to the various plexi of the nervous system. There is the deeper level of the lataif, which has some connection to the glandular system. There is the level that Gurdjieff used, the three centers in the belly, heart, and head. And there are other deeper levels of centers, which are invisible except to essence. To repress the essence completely and efficiently, these energetic and subtle centers have to be shut off, or at most allowed to operate at a minimum of activity and most of the time in distorted and unbalanced ways.

This leads to an overall desensitization and deadening of the body and its senses and to the narrowing and rigidifying of the mind and its activities. The person who knows only personality is not aware of how insensitive and callous he is. This is because he is not aware of how sensitive and refined he could be. He is not aware of how subtle, delicate, and clear his perceptions and actions could be. From the perspective of essence he is a brute, without sensitivity.

The loss of essence, the repression of the subtle organs and capacities, the shutting off and distortion of the subtle and energetic centers, and the overall resulting insensitivity, all lead to a general but devastating loss of perspective. The individual no more knows the point of life, of being, of existence. He no longer knows why he is living, what he is supposed to do, where he is going, let alone who he is. He is in fact completely lost.

He can only look at his personality, at the environment that created it, and live according to the standards of his particular society, trying all the time to uphold and strengthen his ego identity. He believes he is not lost because he is always attempting to live up to certain standards of success or performance, trying to actualize the dreams of his personality—yet all the time he is missing the point of it all.

It is no more the life of being; it is only the life of the personality, and in its very nature it is false and full of suffering. There is tension, contraction, restriction. There is no freedom to be and to enjoy. The true orientation toward the life of essence, the orientation that will bring about the life of the harmonious human being, is absent or distorted.

This loss of perspective and orientation leads to the loss of reality. The individual sees only illusions, follows only illusions, for he takes these illusions to be the reality. We are not talking here only about the neurotic or the pathological individual. Such a person, it is true, does not see the reality of the average and adjusted citizen of society. But this means he does not see the reality of the personality; his personality is incomplete, distorted, or too rigid.

Here we are mostly talking about the normal, adjusted person, one with a more or less complete and well functioning personality. This individual sees the reality of the personality only, and we have seen the truth of this reality, the truth about the personality: that it is not the being but is an impostor, pretending to be the truth.

The most important and tragic aspect of this loss of reality is the loss of what it is to be a complete human being, an individual who has not lost his human element, his essence. In a very real sense, an individual who is not connected to his essence is not a human being because the human element is one's essence. He is still a potential, a human in the seed stage. That is why some of the sages of the past have said that only the wise are human, “the wise” being those who are capable of knowing and being essence. El-Ghazali, the eleventh-century Sufi, puts it this way: “Wisdom is so important that it might be said that mankind is composed solely of the Wise.”8

The condition of most humanity is even more tragic than this. It is not only that the person has lost his humanity; the individual has lost his existence, in the most real sense of the word. An individual who is not being, who is not being essence, is not really existing. He is not in touch with existence because existence, as we have seen, is the deepest aspect and characteristic of essence.

The experience of such an individual, whether normal or pathological, is the experience of the personality. As we have seen, the deepest nature of the personality is a deficiency, a hole, an absence, a nonexistence. So we can add to El-Ghazali's statement: Not only is it true that humanity consists solely of the wise, but also, in the most fundamental sense, only the wise exist.

F ESSENCE IS WHO WE ARE, our true nature, then why is the majority of humanity not in touch with it at all? Why is it something we seek? To answer this question it is useful to observe young children and babies, from the perspective of essence. The many studies of children and babies made by psychologists in the past few decades have developed much useful knowledge. Of course, these studies have not been from the perspective of essence but from social, psychological, or physiological perspectives. They are usually conducted by researchers whose world views do not include essence. But now we need information about essence and young children. We can obtain this information by observing not only with our two eyes but with the subtle capacities of perception, the subtle organs of perception that can be aware of essence directly, without any inference. This is the only way essence can be observed and studied. Then we need to compare these observations with those of adults.

F ESSENCE IS WHO WE ARE, our true nature, then why is the majority of humanity not in touch with it at all? Why is it something we seek? To answer this question it is useful to observe young children and babies, from the perspective of essence. The many studies of children and babies made by psychologists in the past few decades have developed much useful knowledge. Of course, these studies have not been from the perspective of essence but from social, psychological, or physiological perspectives. They are usually conducted by researchers whose world views do not include essence. But now we need information about essence and young children. We can obtain this information by observing not only with our two eyes but with the subtle capacities of perception, the subtle organs of perception that can be aware of essence directly, without any inference. This is the only way essence can be observed and studied. Then we need to compare these observations with those of adults.