During his tour of the Nordic countries, Edward Clarke (1823: 223) came across ‘testimonies of capital crime and punishment [in a Swedish forest] … These consisted of three trunks of fir trees, stripped of the branches and leaves. Upon the tops of which as gibbets were fastened three wheels, for exposing the mangled carcass of a malefactor in three separate parts … this man, it seems, had committed murder.’ He had come across the Nordic equivalent of England’s ‘Bloody Code’. At the end of the eighteenth century, there were 68 capital offences in Sweden and around 300 in England. Executions took place in public across these societies. Tyburn Gallows had been the most well known location for public hangings in England, until this came to an end in 1783 because of the prolonged disturbances associated with these events. Thereafter, executions were usually held outside the local prison – Newgate prison in London, for example – before crowds of up to 50,000. In the Nordic countries, the location of the execution varied: it might be at the scene of the crime, or at a prominent place in the offender’s home community (where, in Sweden, attendance was compulsory for local citizens), or at a crossroads, for obvious symbolic reasons. And, in both clusters, if death itself were not sufficient expiation of the crime, a series of aggravatedpenalties were still available, variously involving the mutilation and exposure of the corpse. Dickens’ (1860/1996) Great Expectations opens with an English country landscape that had gibbeted corpses swinging in the wind in the background. In the Nordic countries, execution usually involved decapitation by axe, followed by dismemberment and the public display of body parts; this is what Clarke had seen.

All the drama and theatre of punishment, and the messages it was meant to convey, were associated with these spectacular public executions. The prison at this juncture played only a minor administrative and significatory role. Used mainly as a holding place until the accused’s fate was determined, its conditions were squalid, disorganized and chaotic, as John Howard discovered in his tours of British and Nordic prisons. In the former, he saw ‘half-starved prisoners, some come out almost famished, scarce able to move, and for weeks incapable of any labour’ (Howard, 1777/1929: 30). As he later reported, things were much the same in the Nordic countries. In Stockholm, for example, ‘one prison had six rooms, four of which, having their windows nailed up, were very dark, dirty and offensive. Here were Swedish prisoners almost stifled, in consequence of receiving no air except through a small aperture in the door of each room. The gaoler here, as in other prisons, sells liquors … His room, like those I have seen too often in my own country, was full of idle people who were drinking’ (Howard, 1792: 83).

Around 1870, however, the death penalty had been almost wholly restricted to offences of murder1 across these societies, and public executions had been abolished.2 Furthermore, all the aggravated death penalties had been removed: in England, the beheading of the corpse, in 1820; gibbeting, in 1832; hanging in chains, in 1834; in Norway, all aggravations came to an end in 1815; from 1832 the body parts and head were to be removed from their poles three days after execution (rather than left indefinitely) and buried; from 1833, the head was still to be placed on a pole after execution, but the body was to be buried immediately after the event; and all displays on the pole were abolished in 1842 (Sørnes, 2009: 55–6). Meanwhile, as punishment to the human body declined in use and became more restricted in scope, so the prison became more central to the development of modern penal systems. The early nineteenth century penitentiary experiments in the United States, involving the Philadelphia separate system (cellular confinement for the duration of sentence with visits only from the prison authorities) and the Auburn silent system (work in association during the day in silence, separate confinement at night), were highly influential in both clusters.3 Ultimately, however, the separate system (with its echoes of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon4) became the prototype for the design and operation of Pentonville Model Prison, opened in London in 1842, and Oslo Botsfengslet [penitentiary], opened in 1851 (see Figure 4.1). In England, another 55 prisons were built in this style between 1842 and 1850 (see, for example, Figure 4.2). Sweden had built 45 ‘separate system’ prisons by the 1880s and, with 2,500 cells, it could house virtually all its prisoners in this way. Although there was more piecemeal development elsewhere in these clusters, separate cell confinement remained the aspiration of both Anglophone and Nordic prison administrators during the second half of the nineteenth century.

| Figure 4.1 | Botsfengslet, Oslo, Norway, seen from across the cabbage field maintained by the prison. Photograph: Wilse/Oslo Museum |

Unremarkable similarities, then, in the respective transitions from pre modern to modern penal arrangements in these societies, and the introduction of a new ‘economy of punishment’, whereby one would now pay for one’s crime through deprivation of time and enforced isolation, rather than intense physical pain (Foucault, 1977). However, there were also important differences in the respective Anglophone and Nordic adaptations of the modern penal arrangements that were then put in place. First, in relation to the death penalty: although it steadily declined in use from the mid-nineteenth century in the Anglophone countries, it remained available as a sanction for murder until the mid-twentieth.5 In the Nordic countries, however, it had virtually come to a de facto end in the 1870s. In Finland, the last execution was in 1826, although formal abolition was not until 1949; in Norway, the last was in 1876 with abolition in 1902; in Sweden, there were only five between 1877 and 1910, with abolition in 1921. Second, in relation to the prison. This became a place of deliberate suffering, hardship and privation in the Anglophone countries during the second half of the nineteenth century. In England, the Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Inquire into the Working of the Penal Servitude Acts ( 1879: 1, our italics) stated that ‘penal servitude is a terrible punishment. It is intended to be so; and so it is’. In New South Wales, the Report of the Comptroller-General of Prisons (1892: 2, our italics) explained that ‘those who complain that prisoners are not reformed in gaols should remember that gaol is not a reformatory, nor is it an asylum. It is a place to which offenders against the law are to serve certain periods under stern and strict discipline as a punishment for crimes and as a warning to others. It cannot reasonably be expected that a prisoner who reaches the hands of the gaol authorities as a dishonest man, with criminal tendencies, can be turned into an upright and respectable citizen by prison treatment.’ And, in New Zealand, the Report of the Inspector of Prisons (1899: 3, our italics) noted that ‘the main object of imprisonment is to punish … [and] it behoves others to undertake the work of reformation’.

| Figure 4.2 | Armley prison, Leeds, exterior, south elevation. An example of the new style prison architecture in the mid-nineteenth century. Photograph: Courtesy of English Heritage |

In the Nordic countries, however, imprisonment was intended to have more productive possibilities, leading to reformation. This had been signalled in the Norwegian Report of the Penal Institutions Committee (1841: 707): ‘there can be no talk of throwing away the fruits of the Enlightenment, civilization and industrialization; hence, the classes who have so far not been able to utilize these must be included in them.’ In these respects, the purpose of imprisonment was designed to bring about the moral improvement of the inmate by ‘making him used to order, discipline and industriousness’, so that he would then become an ‘impeccable, productive and useful citizen’ (ibid. : 462). In Finland, the 1864 Report of the Penal Law Commission stated that ‘the penal law should not be used solely to support general legal security and the maintenance of the authority of the law and to provide for the possibility of meting out punishment in a just proportion to the seriousness of the offence; instead, in a truly Christian spirit it should also attempt to further the reform of the fallen offender and his achieving a new start through the use of measures which can be connected with the force of punishment without the punishment losing its severity and repressiveness’ (quoted by Lahti, 1977: 122, our italics). Even if, as here, severity was to be built into the penal system, this was not to be its only focus: it was to be exercised in combination with other influences intended to make the inmates better people. Indeed, in Sweden in the second half of the nineteenth century, the penitentiaries were referred to as ‘betterment prisons’ (Nilsson, 2003: 9). The Director of the Royal Prisons Board, Sigfrid Wieselgren (1895: 3), thus affirmed that ‘the [separate cell] prisons … replaced the old means of punishment that was obliged to the retribution and deterrence theories; one is looking [instead] to accomplish the perceptible discipline through separate confinement, by which the punishment always should be united with the elimination of bad influences, without which the rehabilitation of the fallen, as far as one can judge, will be made impossible and his human rights violated’.

In such ways, the inclusionary and exclusionary value systems of these societies had already begun to influence their respective courses of penal development: in the Nordic countries, we see moderation and restraint – these societies no longer needed the dramatic excesses of pre modern corporeal sanctions to maintain order and cohesion, and lawbreakers were thought to be redeemable; the prison was not to act as an impenetrable barrier between them and the rest of society. In the Anglophone countries, however, punishment, for most, had come to be remorseless and unforgiving in their modern prisons, rather than confined to a few moments of agony during execution. In these respects, the prison now assumed most of the death penalty’s significatory role, sending out warning messages of its capability to break offenders down and crush them. It was at this point only that reformers could get to work on whatever remained. How, though, did these different adaptations of modern penal arrangements come into place?

One reason for the more rapid termination of the death penalty in the Nordic countries is to be found in their constitutional arrangements. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the monarch was more directly involved in governing the Nordic countries than in England (and its colonies6). In the latter, particularly in the aftermath of the Great Reform Act 1832, parliamentary democracy was well established, and the monarch had already become a largely symbolic non-political head of state. Sweden, in contrast, was still governed by its Diet, and Finland was ultimately ruled by the Russian Tsar. Accordingly, the commutation of Finnish death sentences to transportation to Siberia in 1826 is attributable to the anti capital punishment sentiments of Nikolai I, who became Tsar of Russia and its dominions in 1825. In both Sweden and Norway (where the monarch still held executive powers and responsibilities), the power to commute death sentences was vested in the King in person, rather than a crown minister. In his book On Punishment and Punishment Institutions [Om Straff och Straffanstalter], which was particularly influential because of the high standing of the Swedish monarchy at that time,7 Crown Prince Oscar of Sweden (1840: 11–2) emphasized what, for him, was the repellent nature of this task: ‘before the decision is made, the mind is painfully engaged in a search for what is the most just, and afterwards the memory of the sorrowful topic lies heavily on it … In order to fully comprehend the importance of this remark, it would be necessary to imagine oneself in the place of the Monarch; and to consider, when an average of 61 cases of death penalty sentences yearly are brought forward in Sweden [around three quarters of which were pardoned] how great a portion of his time is taken up, for the nature of these cases cannot be compared with ordinary administrative questions.’ In England and the colonies, however, although decisions regarding commutations and pardons were made by the King in Council, in practice it was the King’s ministers, as members of the Council, who took these decisions (see Gatrell, 1994: 543–4).

But there is more to understanding the different place of the death penalty in the modern penal arrangements of these societies than the whims and consciences of monarchs, on the one hand, and the constitutions of governments, on the other. There is also the way in which their respective cultural values were instrumental in providing different ways of seeing, understanding and thinking about this sanction. This is reflected, first, in the differing modes of knowledge that were brought to bear on this matter, and, second, in the differing behaviour of the crowds at public executions in the two clusters of societies during the first half of the nineteenth century, and the subsequent reactions of the authorities to them.

In the Nordic countries, the most important part of the legislative work of government in the nineteenth century was (and still is) carried out by specialized committees (nominally, at least, independent of government) which considered Bills before they were submitted to parliament. The purpose of these committees has been to interpret legislation in advance in the form of travaux préparatoires (Schmidt and Strömholm, 1964). Furthermore, ‘when a committee is appointed … it is often constructed so that the results of its work cannot be affected by petty things like parliamentary process or public opinion’ (Elwin, 1977: 290): in other words, the experts sitting on the committees drove policy – parliamentary processes and debate became secondary to it. In contrast, law reform bodies in the Anglophone countries – Parliamentary Select Committees or Royal Commissions – had their memberships selected by the government of the day, meaning that these bodies were likely to be dominated by its own members and sympathizers. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the various appointed Nordic Criminal and Penal Law Commissioners were jurists, law professors and civil servants, as well as practicing lawyers andjudges. However, it was the law professors and civil servants who seem to have had the most influence on the contents of the various reports – as was to be expected in these societies in which a high value was placed on education, and where employment in the state bureaucracies carried high status.8

By the same token, judges in these societies have never enjoyed the elite status they have had in the Anglophone. Instead, from the Middle Ages, Nordic judges have sat with lay assessors (who have had the power to override them) in making findings of guilt and deciding sentence. In effect, the Nordic judges were neither above the rest of the community nor detached from it, nor did they wear any of the wigs and gowns that, for the English judges, were meant to signify such superiority and detachment: ‘a Swedish law court studiously avoids all the bewigged pomp and circumstance of a British court’ (Austin, 1970: 45). Rather than being selected for a life ‘on the Bench’ on the basis of charismatic and dazzling courtwork, as in England, the Nordic judges have trained for this profession as a career (‘high flown eloquence and appeals to sentiment [by counsel] are almost completely unknown in Sweden’: Schmidt and Strömholm, 1964: 11). Beforehand, they are likely to have been career civil servants, with experience in drafting Bills, or other forms of judicial administration. They thus have different experiences of life than the Anglophone judges, with their privileged backgrounds – most certainly in the nineteenth century – revolving around private education or attendance at leading public schools and universities, followed by induction in courtroom gossip and anecdote.9 Such elitism in England had been further strengthened by the judges’ constitutional standing as a counterweight to any overreaching parliaments. However, in the Nordic countries, any such displays of pomp and grandeur were wholly out of place. In addition, the judges were not exempt from the insistence on uniformity and consensus: ‘among the general public … there is much suspicion against an independent judiciary … All in all contemporary political life reflects a general view that the judiciary may not carry out a policy of its own but must identify itself with the policy of the ruling majority’ (Schmidt and Strömholm, 1964: 36, our italics). At the same time, the Lutheran heritage provided an innate caution against making outspoken, condemnatory judgments of others. Thus, while the Nordic judiciary are likely to consider themselves as members of a select corps within the public service, they have never looked upon themselves as having greater influence or ‘say’ in public affairs than other officials. Their task has been to state what the law is, without the pontificating and moralizing that came to be one of the characteristics of the Anglophone judges10 whose status, upbringing and constitutional position encouraged them to do exactly this. At the same time, the scope for Nordic judges to act in such ways was, anyway, greatly restricted: the intent of the law had already been set out for them in the accompanying legislative prescriptions. In contrast, in the common law Anglophone societies, it was the judges who interpreted intent and fitted this to existing case law (which, in itself, was framed through their own elitist understandings of the social order).

Accordingly, the respective law commissions and advisory bodies set up to bring about the modernization of penal law in the early nineteenth century brought very different modes of knowledge to this task. In the Nordic countries, Enlightenment thought was very influential, particularly Beccaria’s (1764) On Crimes and Punishments (it had been translated into Swedish in 1770). He was opposed not only to the aggravated death penalties of the pre modern world, but the death penalty itself: ‘the punishment of death is pernicious to society, from the example of barbarity it affords. If the passions, or the necessity of war, have taught men to shed the blood of their fellow creatures, the laws which we intended to moderate the ferocity of mankind should not increase it by examples of barbarity.’ In addition, he envisaged a democratization of the criminal justice process. Rather than the criminal law being used to uphold the privileges of the powerful, legal power and authority should be invested, instead, in the civic body as a whole: ‘laws which surely are, or ought to be, compacts of free men, have been, for the most part, a mere tool of the passions of some, or have arisen from an accidental and temporary need. Never have they been dictated by a dispassionate student of human nature who might, by bringing the actions of a multitude of men into focus consider them from this single point of view: the greatest happiness for the greatest number’ (ibid. : 12). At the same time, the quantity of punishment to be imposed should be proportionate to the crime committed (to prevent unnecessary excesses) and determined in advance in penal codes written by these ‘dispassionate students of human nature’, rather than left to the discretion and whims of judges: ‘when a fixed code of laws, which must be observed to the letter, leaves no further care to the judge than to examine the acts of citizens and to decide whether or not they conform to the law as written: when the standard of the just or the unjust, which is to be the norm of conduct for all; then only are citizens not subject to the petty tyrannies of the many which are the more cruel as the distance between the oppressed and the oppressor is less, and which are far more fatal than that of a single man, for the despotism of many can only be corrected by the despotism of one; the cruelty of a single despot is proportional, not to his might, but to the obstacles he encounters’ (ibid. : 24).

Such ideas – reductions in the intensity of punishment, with a view to bringing about greater social cohesion, and codification as a means to preventing tyranny – variously informed the Nordic penal reform commissions of this period. The Swedish Law Commission (1815) took the view that the death penalty was ‘barbaric and could only make people hardened and alienated towards the law … It could neither improve nor deter and goes against the civilisation of the times.’ It was the opinion of the Commission that the sanction would disappear altogether as society itself continued to evolve, driven on by the emphasis now given to rationality and science, rather than the superstitions and emotions of the pre-modern era, even if the Commission was not convinced that this level of cultivation had yet been achieved in Sweden (which led to its decision to recommend the retention of the death penalty for murder cases and those that endangered ‘the safety of the state’). In addition, the Commissioners situated penal reform in the context of broader international developments, as if, in so doing, this gave further legitimacy to their proposals: these would ensure that Sweden would be part of the progressive, post Enlightenment world of reason and civility that was sweeping through the rest of Europe. Thus, the Swedish Law Commission’s (1826) Propositionrefers to German and French jurisprudence, as well as abolitionist reforms in other jurisdictions – Hanover, Saxony, Wurtemberg and Weimar in Germany, Swiss cantons, and Louisiana in the USA. As a subsequent Proposition (Swedish Law Commission, 1832) concluded, the continued presence of the death penalty went against ‘the civilization of the times’. Furthermore, any arguments based on the supposed deterrent effect of the death penalty had little purchase in these homogeneous, egalitarian and poor societies. There were no great accumulations of wealth and property that needed to be protected from the prédations of the lower classes by this sanction; and its use appeared unseemly and unnecessary because of the sense of solidarity that the high level of uniformity in the population had created: those who were executed were likely to be seen as being just the same as any other citizen, rather than wild outsiders.

In addition, in societies where moderation and restraint were paramount, revenge and the emotions underpinning it should have no place in the administration of punishment. Crown Prince Oscar ( 1840: 6) thus wrote of the quandary of retaining the death penalty: ‘society has undeniably the right, as well as the duty, to punish every action which can interrupt the public order of justice … But should this right go further than the loss of freedom? Every punishment that reaches outside of this boundary enters the territory of revenge.’ The Norwegian Report of the Penal Institutions Commission (1841) thus argued that the death penalty should be abolished: those who supported it ‘didnot understand human nature – utterly harsh punishment hardens instead of deterring.’ Instead, it was the duty of the Norwegian state to move the human race towards its ‘great goal’ of allowing ‘justice and truth to rule in a reasonable world’, without the need for its authority to be upheld by such a dramatic sanction; this was how the world should be (even if at that time, it was still thought necessary to retain the death penalty in ‘extreme cases’, specifically premeditated murder, aggravated robbery with loss of life, and treason). In Finland, the decision on whether the de facto abolition of the death penalty that had been in place since the 1820s should become de iure periodically resurfaced, as successive law reform commissions resumed their work on drafting the penal code. That of 1862 had proposed to retain the death penalty for treason and murder, safe in the knowledge that any such sentence would be automatically commuted to transportation, following Nikolai I’s dictat. Here, too, prominent jurists played a leading role in popularizing the abolitionist cause, particularly Karl Gustav Ehrström, Professor of Law at the University of Helsinki. For him, the death penalty represented ‘the disgrace of our time’. In a series of newspaper articles in 1859, he explained that reducing crime was not attainable by fear, but through the strength that came from religious and moral education: ‘punishment has to be a just atonement that should generate the reform of the offender’ (quoted by Blomstedt, 1964: 439–40).

However, Enlightenment influences were much less prominent in corresponding attempts to modify penal law in England. When introducing legislation to restrict the availability of the death penalty in 1808, Sir Samuel Romilly, then the country’s leading jurist and an enthusiast, himself, of Beccaria, complained that ‘in the criminal law of the country, I had always considered it a very great defect that capital punishments were so frequent … No principle could be more clear than that it is the certainty, much more than the severity of punishments which renders them efficacious. This had been acknowledged ever since the publication of the works of the Marquis Beccaria; and I have heard … that upon the first appearance of that Work it produced a very great effect in this country. The impression, however, had hitherto proved unavailing; for it has not, in a single instance, produced any alteration of the criminal law; although in some other states of Europe such iterations have been made’ (Hansard [UK], HC Deb, 18 May 1808, col. 395, our italics). Indeed, any limitations on the Bloody Code were unwelcome amongst powerful sections of British society. Lord Ellenborough, for example, a judge himself, was of the view that ‘terror alone could prevent the commission … of crime … although the law as it stood was but seldom carried into execution, yet the terror was precisely the same … the apprehension of no milder punishment would produce anything like safety to the public interest’ (Hansard [UK], HL Deb, 30 May 1810, col. 197, our italics). In societies with such lengthy social distances and wide social divisions as England, there was still a place for terror in its penal practices: these made it too insecure a society to do away with this sanction, while the lack of interdependencies that was the result of these divisions gave no encouragement to the development of abolitionist sentiments. Indeed, it was claimed that Romilly’s intentions to reduce the ferocity of punishment were based on mere ‘speculation’ and ‘theories’ – which was enough to damn them in a society that preferred hard facts to ideas, and was highly suspicious of its intellectuals. Sir James Mackintosh MP, for example, thus preferred ‘the testimony of bankers and merchants to the mere declarations of the learned gentlemen’ (Hansard [UK], HC Deb, 23 May 1821, col. 967).

Thus, while the infliction of the death penalty was indeed restricted during the first half of the nineteenth century in England, there was little reference to this being part of a more general move towards a ‘better society’ that was characteristic of similar developments in the Nordic countries. Instead, reducing its availability was justified on the basis that this would make the criminal justice system more efficient and more of a deterrent than it currently was. The multiplicity of death sentences only created sympathy for offenders: juries refused to convict and, even if they did, judges might then use their discretionary powers to avoid execution. As a consequence, justice, Romilly (1820: 126) explained, had become a ‘lottery.’ Fewer and less severe penalties – but greater regularity in their imposition – would bolster the element of fear in the criminal justice system while eliminating the ‘dangerous sympathies’ for the offender caused by the capricious brutality of the Bloody Code. In this way, punishment would be used more sparingly but with greater certainty: it would inevitably expel and destroy under these circumstances, thereby more effectively bolstering and protecting the existing social structure and its divisions and hierarchies (McGowen, 1983). In contrast, in the more egalitarian Nordic countries, the death penalty was not needed for these purposes: this sanction, it was anticipated, would eventually have no place in the ‘reasonable world’ that these societies were moving towards, one where ‘justice and truth’ would prevail.

These Enlightenment principles were then built into the penal codes that the respective Nordic law commissions drew up during the nineteenth and early twentieth century: codification was essential to ensure that the quantity of punishment was determined by experts at this stage, rather than judges presiding in a particular case: the Nordic judges had no right (nor did they claim any such right anyway, given the different juridical cultures of these societies) to stand between government intentions and policy development. However, attempts to limit judicial discretion in England for these same purposes were met with fierce resistance (resulting in consolidation, but not codification, of the criminal law in the 1860s): the different standing of judges gave them the right to occupy exactly that position. Replying to a further attempt by Romilly to reduce the number of capital statutes in 1813, the Solicitor-General stated that ‘if discretion must be vested somewhere, where it could be so safely reposed than as with the judges of the land? Always reserving too, an appeal to the fountains of mercy – an appeal which, whenever good cause could be shown in support of it, had never been made in vain’(Hansard [UK], HC Deb, 17 Feb 1813, col. 562). Indeed, it was as if the intended modernization of penal law was merely some sort of undesirable continental practice that led to greater tyranny rather than less, endangered individual freedom rather than protected it: William Windham MP stated that ‘he could not help looking with an eye of jealousy on all such visionary schemes, which had humanity and justice for their ostensible causes. What had we witnessed within the last 20 years? Had not the French revolution begun with the abolition of capital punishments in every case? But not till they had sacrificed their sovereign, whom they had thus made the grand finale to this species of punishment’ (Hansard [UK], 1 May 1810, col. 768). In this society, punishment, in the form of the death penalty and the signs and symbols it gave out, was seen as a guarantee of freedom (it would frighten the lower classes, in particular, away from crime), whereas in the Nordic it was thought to endanger freedom.

By the same token, the standing of the English judges and the deference to their opinion also ensured that they, rather than any criminal law intelligentsia, were particularly influential on the law reform bodies. This can be seen in the conclusions of the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment (RCCP), which sat from 1864 to 1866. Its membership consisted of one lord, eight MPs (five of whom were lawyers), two judges and one civil servant. It had been convened to consider ‘the provision and operation’ of capital crimes and whether ‘any alteration is desirable … in the manner in which such sentences are carried into execution’. To these ends, it heard evidence from 36 witnesses and, in addition, ‘the opinions of all Her Majesty’s judges as well as of other prominent criminal lawyers have been researched’ (RCCP, 1866: 1, our italics). The Commission was not prepared to consider the case for abolition but, instead, took the view that, in addition to treason cases, the death penalty should remain for those murders committed with ‘malice aforethought’. What seems to have influenced it, and have given it the authority for its conclusions, was the evidence of the judges and ‘prominent lawyers’ in the extensive discussions on the deterrent effects of this sanction. Although 30 witnesses were heard on this particular matter, with only the narrowest of majorities (16-14) in the affirmative in the evidence, the judges and barristers unanimously maintained it did act in this way. Only one jurist gave evidence – the little known Dr Leone Levi, Professor of Commercial Law at the recently established, but still low status, King’s College, University of London (it then offered only evening classes to ‘working people’). Levi was an abolitionist, and quoted Beccaria in support of his arguments. However, his evidence was then followed by that of James Fitzjames Stephen, barrister-at-law and judge, educated at Eton, Britain’s most exclusive public school, and Trinity College, Cambridge, and subsequently renowned for his views that ‘criminals should be hated’ (Stephen, 1883: 82). In his opinion, based entirely on the death penalty cases in which he himself had prosecuted or adjudicated, ‘the sentence of capital punishment deters people from crime more than any other … people are aware that murder is punishable by an ignominious expulsion from the world. They therefore get to consider murder as a very dreadful thing. They associate it with an ignominious death long before they have ever had any notion of committing the crime’ (Minutes of Evidence, RCCP, 1866: 254). He peremptorily dismissed international evidence that contradicted his assumptions. When questioned about Tuscany, for example, where the death penalty had been abolished for 80 years, his reply was that, ‘I do not know anything about the state of society, or the national character or the circumstances of Tuscany and I therefore cannot give an opinion on that point … what I have written upon the subject I have based principally upon my own experience’ (ibid.: 255).

The evidence of three of England’s leading judges, all members of the Court of Exchequer,11 was similar in tone. Lord Cranworth (also educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge) maintained that ‘murder is a crime so much beyond all other ordinary crimes, that I think society is justified in restricting, as far as possible, its commission by the most deterring punishment, and I have no doubt whatever that the fear of death is infinitely more deterring than the fear of any other punishment’ (ibid.: 1). For the privately educated Baron Bramwell, ‘you punish because the law threatens punishment; if punishment were not inflicted, the law which threatened it would be idle.’ As for the international abolitionist trends, his view was that ‘we cannot rely upon the effects of a change from capital punishment to some other punishments in foreign countries because we do not know enough of the particulars to place any dependence on the reported results’ (ibid.: 29–31). As with Stephen, evidence from societies that showed how it was possible to live without the death penalty was not thought worth considering. Baron Martin, educated at Winchester (a close rival to Eton) and Trinity College, Dublin, acknowledged that he appeared ‘very seldom in a criminal court’ but was nonetheless confident that ‘for the purpose of forming a real judgement upon the efficacy of capital punishments you must have recourse to persons who are well acquainted with the lower classes … my idea is that punishment must be a terror to them, and that in the event of the committing of murder they will be punishable by death’ (ibid.: 56, our italics). The main body of the Nordic penal law intelligentsia had taken the view that the death penalty was associated with pre modern excesses that should have no place in the modern world, a world to which they wished to belong, and a world that was now offended by the presence of the death penalty, as they saw beyond their own Nordic boundaries. Here, though, such lofty ideals were irrelevant to the senior judges and lawyers who provided pivotal opinion on its future in the Anglophone societies. For these elite members of British society, it remained a necessary sanction if the awe and power of the state, that was embodied in it, was to be maintained: punishment still needed to be a ‘terror’ to those on whom it would be inflicted – ‘the lower classes’ – far removed from the high status coterie who decided this on their behalf. Furthermore, failure to use this sanction when it was available would only bring the law and, by inference, the judges, into disrepute.

By the mid-nineteenth century, crowd behaviour and the general conduct of public executions also demonstrated great differences in the way in which the death penalty was seen and understood in the two clusters of societies. The 1840s witness accounts of William Thackeray, in England, and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, in Norway, provide clear illustrations of these differences. Thackeray (1840: 154–6) described the execution of François Courvoisier outside Newgate prison: ‘the character of the crowd [at 6.00 am] was as yet, however, quite festive. Jokes bandying about here and there, andjolly laughs breaking out. All sorts of voices issued from the crowd, and uttered choice expression of slang … the front line, as far as I could see, was chiefly occupied by blackguards and boys – professional persons, no doubt, who saluted the policemen on their appearance with a volley of jokes and ribaldry … the audience included several peers, members of the House of Commons, a number of ladies armed with opera glasses, some foreign princes and Counts … from under the black prison door a pale quiet head peered out. It was shockingly bright and distinct; it rose up directly, and a man in black appeared on the scaffold, and was silently followed by about four more dark figures. The first was a tall, grave man: we all knew who the second man was. “That’s he, that’s he”, you heard the people say … His mouth was constricted into a sort of pitiful smile. He went and placed himself at once under the beam … the tall grave man in black twisted him round swiftly in the [right] direction, and drawing from his pocket a night cap, pulled it tight over the patient’s head and face. I am not ashamed to say that I could look no more, but shut my eyes as the last dreadful act was going on which sent this wretched guilty soul into the presence of God … 40,000 persons of all ranks and degrees – mechanics, gentlemen, pickpockets, members of both Houses of Parliament, street walkers, newspaper writers, gather together at Newgate at a very early hour; the most of them give up their natural quiet night’s rest, in order to partake of this hideous debauchery, which is more exciting than sleep, or wine, or the last new ballet, or any other amusement they can have. Pickpocket and peer, each is tickled by the sight alike.’

Bjørnson (1898: 113, our italics) remembered how, as a child, he had watched the execution of Peer Hagbo in Norway in 1842. This had taken place at a crossroads seven miles from Hagbo’s village. As the procession, made up of the condemned man, the clergy and a military escort, moved towards it, ‘by the wayside stood people curious to see [Hagbo], and they joined the procession as it passed along. Among them were some of his comrades, to whom he sorrowfully nodded. Once or twice he lifted his cap … it was evident that his comrades had a regard for him; and I saw, too, some young women who were crying, and made no attempt to conceal it. He walked along with his hands clasped at his breast, probably praying … A great silent crowd stood round, and over their heads one saw the mounted figure of the sheriff in his cocked hat. The Dean’s speech [in Danish] was neither heard nor understood, but it was short. His emotion forced him to break off suddenly. One thing alone we all understood: that he loved the pale young man whom he had prepared for death, and he wished that all of us might go to God as happy and confident as he who was to die today. When he stepped down they embraced each other for the last time … [Bjørnson’s father, the local pastor, then spoke], following up the thunderous admonition of the execution itself, he warned the young against the vices which prevailed in the parish – against drunkenness, fighting, unchastity and other misconduct … as for me, I left the place sick at heart, as overwhelmed with horror, as if it were my turn to be executed next. Afterwards I compared notes with many others, who owned to exactly the same feeling.’

Both authors were profoundly affected by what they had witnessed – but they had witnessed very differently conducted events. For Thackeray, the crowd’s total lack of empathy for Courvoisier seemed even more disturbing than the execution itself. Crowd behaviour had not always been like this on these occasions, though. In the eighteenth century, it could be sympathetic to the condemned, to the point of trying to rescue them, or bawdy and insensitive ; similarly, the condemned might make a bold speech against injustice, might be joyfully anticipating an imminent heavenly welcome, or might be desperate with fear (see Radzinowitz, 1948; Gatrell, 1994). Now, however, with the weakened social bonds and interdependencies brought about by industrialization and urbanization, the loss of another person’s life, in this particularly demeaning and humiliating way, led only to carnival and ribaldry (probably exacerbated by the increasing rarity of these occasions12) – nothing more than this. Meanwhile, Courvoisier’s exchanges with the crowd had been reduced to ‘the pitiful smile’ he gave before the hood was placed on his head. In the pre modern era, the fate of the condemned had often been vicariously shared by the crowd, as if they experienced the pain of one of their fellow citizens being torn away from them. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, the unity between the onlookers was brought about by avid curiosity and unrestrained celebration that the imminent despatch of the person on the scaffold – now known only on the basis of his difference to the surrounding crowd – provoked.

At the Norwegian execution, though, it was as if those in attendance had no wish to lose a citizen who still seemed very similar to themselves in all other respects. The loss was met with sorrow, rather than celebration. In addition, the pastor played a much more central role in the event than the chaplain in England, where their public ministrations had become minimal. Indeed, whereas Thackeray is preoccupied with the crowd scene, Bjørnson gives predominance to the work of the pastors. On such occasions, the pastor’s presence marked the culmination of lengthy preparations with the condemned (that sometimes could take months). It was the pastor’s duty to instruct the prisoner that it was possible for the latter to influence his own salvation, and that it was never too late to ask for God’s forgiveness, no matter what the crime had been: for Lutherans, forgiveness did not come from deeds, but from faith. Sofie Johannesdatter, who was, in 1876, the last woman to be executed in Norway, is reported to have said before her beheading, ‘“Now I am going home to Jesus.” She then read a hymn to the 3,000 people who had gathered to watch the execution’ (Aftenposten, 18 February 1876: 1). At the same time, such occasions obviously provided the pastors with the opportunity to affirm their own civic authority in these communities – for which there was, then, no equivalent in the more fractious Anglophone societies.13

Not every Nordic execution followed the pattern described by Bjørnsen;14 nonetheless, the solemnity of the occasion and the sorrow of the crowd were the predominant themes of nineteenth-century witness accounts in Norway and Sweden. Clarke (1823: 261, our italics), describing an execution in Stockholm, noted that ‘at nine in the morning the throng in the road was so great that carriages could not approach. Many spectators were in tears.’ Not only this: it also seemed that the executions were likely to threaten social cohesion and solidarity, rather than bring fragile unity, as in England. After another execution in Stockholm, ‘An Old Bushman’ (1865: 84) observed that ‘if the public papers speak the feelings of the people, in all probability this will be about the last capital punishment in Sweden.’ Indeed, the influential Swedish law professor, Knut Olivecrona (1866/1891: 237, our italics), in On the Death Penalty [Om dödsstraffet], maintained that ‘the execution of the death penalty has a demoralizing effect on the people’. After it took several blows of the axe to deliver the coup de grâce to Olaves Andersson, near Oslo, Aftenposten (17 July 1868: 1) complained that ‘outstanding people from all kinds of professions now want to abolish the death penalty. Why do the authorities need to force a man to perform the barbaric act of chopping the head off another man with an axe?’

While there were a handful of private executions still to come in Norway and Sweden from 1870 to 1910,15 this sanction was allowed to fall into disuse in this region with little further controversy. In Norway, it ceased to be mandatory for murder in 1867, although, by then, commutation to life imprisonment had become the norm, rather than the exception, in these cases. Rather than routine commutation bringing the law into disrepute – the fears of some of the English judges – it was claimed in the Norwegian parliament that ‘it is almost 20 years since the last execution was held in this country, and the consistent use of the right to pardon seemed not to have offended the common sense of justice or reduced the rule of law’ (Stortinget, 1896: 27). Indeed, it was more likely that these sentiments were strengthened by commutation rather than weakened by it: again, judges were expected to support public policy, not demonstrate their detachment from it. Thereafter, the abolition recommendations of the 1896 Penal Code Commission, with Professor of Law Bernard Getz as its chairperson, were incorporated in the 1902 Penal Code. In Finland, the recommendation of the 1880 Law Commission that the death penalty should be optional in murder cases was finally incorporated in the 1889 Penal Code. Although six death sentences were passed between 1895 and 1917, these were all commuted. There were no more, in peacetime conditions, before eventual de iure abolition. In Sweden, Olivecrona (1866/1891: 199) proclaimed that, ‘while the process of civilization has ensured that many of the previous barbaric practices and punishments, such as slavery and torture, have disappeared … it now only remains to obliterate the death penalty – this last remnant of barbarity’. As a member of the nobility estate, he had been able to put forward these views in the 1863 Penal Code debates in the riksdag, resulting in it becoming an optional penalty in murder cases in 1864. After being made a judge of the Supreme Court in 1868, he was then able to ensure that virtually all applications for pardons and commutations were granted. In the foreword to the second edition of On the Death Penalty, he (ibid.: i) maintained that ‘with the level of civilization now reached amongst the Swedish people, the death penalty is no longer absolutely necessary to fully secure the legal security in the country, and as all punishment that oversteps the limit of necessity, it is unfair and should no longer be used’. That is, the stability and cohesion of this society did not need the threat of this sanction to reinforce it. Eventual abolition in Sweden, in 1921, was mentioned by only one newspaper, which simply stated the decision had been ‘long overdue’.16 This was what the awe and theatre once associated with the death penalty had been reduced to: an irrelevance to the social arrangements of these societies, which were conducted according to the principles of moderation and restraint.

However, while the Nordic authorities had wanted to protect the crowd from the sights of public executions, in England it was the behaviour of the crowd itself, rather than the executions, that had become repellent to observers such as Thackeray. At the execution of Franz Muller, The Times (15 November 1864: 5, our italics) complained that ‘he was hung in front of Newgate. He died before such a concourse as we hope may never be again assembled either for the spectacle which they had in view or for the gratification of such lawless ruffianism as yesterday found its cope around the gallows … Muller died with dignity, the only one showing this.’ But, both the Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords (1856) and the RCCP (1866) recommended the abolition of public executions, while maintaining support for the death penalty per se. Sensibilities relating to the death penalty extended to the manner of its application but not its very existence. Here, the death penalty seemed to maintain and secure the social fabric rather than endanger it. When conducted with due solemnity, its presence, even if now set ‘behind the scenes’, would continue to provide an important symbolic message in these more divided and less solidaristic, less forgiving, societies. On this more restricted basis, capital punishment maintained the support of prominent public figures such as Dickens, Thomas Carlyle and John Stuart Mill.17 The shift from public to private executions, rather than abolition, also occurred in New Zealand and New South Wales, notwithstanding some settlers who argued that public executions gave important messages to Maori and Aborigines about the might and strength of Imperial power (although there were also worries amongst them that this mode of execution put disconcerting ideas into the heads of these indigenous races).18

Ultimately, while the abolition of the death penalty was taken for granted in the Nordic countries at this juncture, it was its retention – as a punishment to be carried out in private – that was taken for granted in the Anglophone. In England, The Times (14 March 1878: 9, our italics) reported that ‘the storm which once seemed to be gathering has subsided and has been followed by a great calm. Abolition no longer has a place among the real questions of the day.’

During the first half of the twentieth century, there were further restrictions on the use of the death penalty in the Anglophone countries (it had already fallen into abeyance in New South Wales before final abolition19). Any ostentatious remnants of its presence, such as tolling chapel bells and the hoisting of a black flag at the prison where the execution was taking place, were removed, and press attendance was prohibited from 1934 in England, so that its only public manifestation would be in the form of a small death notice posted outside the executing prison. Nonetheless, important sectors of these societies clung on to this sanction, still fearing that social order would collapse without its support.20 These included senior judges and leading members of the Church of England, most members of the respective Conservative parties, most of the British House of Lords, and, post-1945, a sizeable majority of public opinion.21 In these societies, replete with barriers and divisions, with strong senses of individuality but weak interdependencies, where extensive social distances led to fears and fantasies rather than restraint and moderation, the presence of the death penalty, even if now more symbolic than real,22 was still needed. It protected the rest of society against the monstrous outsiders that seemed so much more plentiful here than in the more homogeneous Nordic countries. ‘Why should depraved creatures … be kept alive, imprisoned at vast expense to the public purse, spreading corruption with their baleful influence … with the opportunity of hatching further diabolical plots against their fellow men?’ (Hansard [UK], HL Deb, 19 July 1965, col. 456). In New South Wales and New Zealand, especially, those who argued against this were regularly accused of ‘sentimentality’: those who had failed to prosper in these lands of opportunity should be held responsible for their own fate. Indeed, in these colonies it was thought that there was something effete and unmanly about arguing for abolition and about the fanciful metaphysics on which the abolitionist cause was based: ‘whether we deal with this from an emotional or sentimentalist point of view, or what is called a humanitarian point of view, we have eventually got to deal with the world as it is, and the world is not made up too much of sentimentality or emotion but of the stern facts of reality’ (Hansard [NSW], 3 Sept 1925: 578); ‘all this pseudo-humanitarianism is undermining our social stability’, (Hansard [NSW], 23 March 1955: 3257); ‘in my opinion, the evidence of those men of practical experience deserves far greater weight than the evidence of what I should like to call … misguided sentimentalists’ (Hansard [NZ], 16 Nov 1950: 4285).23 By the same token, during the first half of the twentieth century, research that contradicted the death penalty’s assumed deterrent powers could be simply ignored. As usual in these societies, the work of experts and intellectuals was held in low regard: one British MP thus claimed that ‘statistics do not conclude the matter. Not all human reactions can be measured by statistics, and statistics of crime have little to say about the deep-seated beliefs that govern the conduct of those who refrain from crime … It is important that murder should be regarded with peculiar horror – that horror is in itself a powerful psychological barrier against killing. Since statistics give us no help, let us try common sense. Death, I should have thought, is more feared than any other punishment’ (Hansard [UK], HC Deb, 16 Feb 1956, col. 2560). In contrast, the support of public opinion for this sanction was thought to be a further justification for retention. The thinking of ‘ordinary people’ – always a potent argument in these countries – should lead policy development, rather than have this entrusted to the state and its officials. As the Conservative peer Lord Salisbury24 explained in 1956, ‘abolitionist members [of parliament] are not only ignoring their electors, but defying them. The public must be trusted all the time, and we must be guided by their views when they are ascertainable, whether we personally consider them right or wrong. Anything else makes nonsense of our democracy’ (quoted by Christoph, 1962: 149–50).

Nonetheless, it was in the post-war period that social cohesion finally seemed strong enough to hold together without the prop of the death penalty. Only now did it become possible, in these Anglophone societies as well as the Nordic, to argue that ‘we do not punish for the sake of punishment. Retribution has long since ceased to have any relevance’ (Hansard [NSW], 24 March 1955: 3226). In an editorial in support of abolition, The Times (18 December 1964: 11) made the point that ‘execution has degenerated into a totem, and totems have no place in adult societies’: the drama and emotion that this penalty had previously invoked, to help hold this society together, had become superfluous. Indeed, at this junction, there was also more willingness to allow rationality and knowledge to supersede common sense and anecdote in the determination of policy. In a debate on capital punishment in the New South Wales Assembly, it was thus claimed that ‘psychology and psychiatry have a greater place in deciding what punishment shall be inflicted on offenders. The modern school favours corrective punishment – over the oldrevenge or deterrence’ (Hansard [NSW], 28 May 1949: 574). In England, a new RCCP was established in 1949, with its 12 members now including the famed Professor Leon Radzinowitz, a psychologist, ‘a writer’, a trade unionist, a professor of law, and two lawyers – but no judges. Its subsequent conclusion (RCCP 1953, para 65) that ‘there is no clear evidence that the abolition of capital punishment has led to an increase in homicide’ removed its deterrent credibility, and was influential in Australia and New Zealand, as well as England.25 At the same time, a new belief in the power of the state, after its wartime accomplishments, would allow public opinion to be overridden: as one British abolitionist MP put the matter, ‘I doubt very much whether at the moment public opinion is in favour of the change, but … there are occasions when this House is right even if the public may not at that moment be of that opinion’ (Hansard [UK], HC Deb, 10 February 1955, col. 2083).

While it remained, for some, a legitimate symbol of the state’s power to punish, the death penalty had now also become a symbol of tyranny and barbarity that had no place in the Western democracies: ‘repressive punishments belong to the systems of totalitarian states and not democracies. It was no accident that the chief exponents of violence and severity in the treatment of criminals in other times were Nazi and Fascist states’ (Hansard [UK], HC Deb, 14 April 1948, col. 1014–5). Even so, although abolished in New South Wales in 1955 and New Zealand in 1961, it endured a lingering death in more divided England: it was merely ‘suspended’ in 1965 (the House of Commons voted 200 to 98 in favour, the House of Lords 204 to 104), before final abolition in 1969.

These clusters of societies had had a shared involvement in the birth of the modern prison. Why, then, did their respective prison systems begin to diverge so sharply in the second half of the nineteenth century?

What the purpose of prison should be had been highly contested in England from the 1840s to the 1860s. The champions of the separate system as put into practice in this country (18 months of isolation from 1842, rather than the entire sentence as at Philadelphia; and then reduced again, to nine months in 1850, following concerns about its deleterious mental and physical effects26), particularly the prison chaplains, believed that it could bring about the prisoners’ penitence and reformation (Anderson, 2005: 147).27 Indeed, in the mid-nineteenth century, the chaplains were pivotal figures in the administration of English prisons, reporting only to the governor and even, in some instances, sharing prison management with them (see, for example, Nihill, 1839). However, the design and administration of the new model prisons that were conducive to the separate system also provoked great criticism: while less eligibility had been injected into the administration of the Poor Law, it had not yet found its way into the penal system – quite the contrary, in fact. The journalist Hepworth Dixon (1850: 153) found that, at Pentonville, ‘the diet is better, richer than in other prisons’. And Mayhew and Binney (1862: 120), also visiting Pentonville, reported on the ‘wondrous and perfectly Dutch-like cleanliness pervading the place … [It was] extremely bright and cheerful … with its long, light corridors, it strikes the mind, on entering it, as a bit of the Crystal Palace, stripped of all its contents.’ Furthermore, Home Office civil servants were, at the time, of the opinion that it would be unconscionable for the prison diet to be used as ‘an instrument of punishment’ – hence Dixon’s comments, and those of Mayhew and Binney (1862: 130) that ‘the most genuine cocoa we ever supped was at a Model prison’. However, these conditions of confinement seemed utterly luxurious when compared to those of most of the populace, as Dickens (1849–1850/1992: 714) satirized in David Copperfield: making a tour of what was meant to be Pentonville, Copperfield observed that ‘it being, then, just dinner time, we went first into the great kitchen, where prisoners’ dinner was in the course of being set out separately, with the regularity and precision of clockwork … I wondered whether it occurred to anybody that there was a striking contrast between these plentiful repasts of choice quality and the dinners, not to say of paupers, but of soldiers, sailors, labourers, the great bulk of the honest, working community; of whom not one man in 500 ever dined half so well.’ Similarly, the essayist Thomas Carlyle (1850:44) wrote of one ‘palace prison’ he visited: ‘gateway as to a fortified place; then a spacious court, like the square of a city; broad staircases, passage to interior courts; fronts of stately architecture all round … surely one of the most perfect buildings within the compass of London’. Such was the disquiet at the revelations of conditions within these ‘palaces’ that the architect Henry Roberts (1850: 4) warned that ‘the nation surely cannot long allow such a contrast to exist between the comparative domiciliary comforts enjoyed by those who have forfeited their freedom as the penalty of crime, and the wretched home from which at present too many of our labouring population are tempted to escape to the gin palaces or the beer shops’.

In these new prisons, those whose criminality had made them the least deserving members of these societies experienced little of the miseries of institutionalization now forced on those whom not even the most hard-nosed economic liberal could hold responsible for their own travails: workhouse orphans such as Oliver Twist (Dickens, 1838/1992), for example. The Prisons Acts of 1865 and 1877 were intended to rectify these distortions and injustices, and the way chosen to do this was by lowering the living conditions in the prisons, rather than raising those in the workhouses. Driven by the ferocity of the criticisms of the ‘palace prisons’, the Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on Prison Discipline (1863) had recommended that imprisonment should be used for deterrent, rather than reformative, purposes. Accordingly, the first part of the progressive stage system (initial separation followed by increasing levels of association with other prisoners) would be transformed from being a period of reflection and penitence to one that was intended to break the spirit of the prisoner: ‘the especially penal character of the first month of sentence – a period of strict and so far as is possible, unbroken isolation – is maintained for all prisoners’ (Report of the Commissioners of Prisons, 1884: 11). But this, rather than being the centrepiece of the prison experience, as originally envisaged, was merely the preliminary to a much more systemic routine designed to break and overwhelm.28

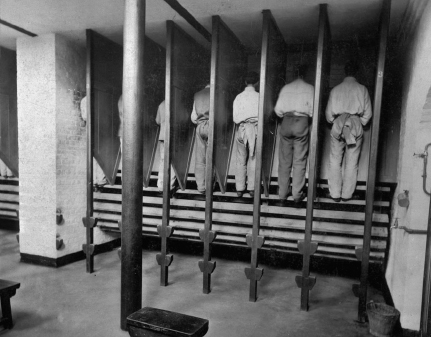

This was to be achieved by unifying and modelling the prison regime on ‘hard bed’, ‘hard fare’ and ‘hard labour’ principles, as provided for in the legislation of 1865 and 1877. It was Du Cane who then put these principles into effect (and those who served under him subsequently brought his ideas to the colonies of Australia and New Zealand29). Now, less eligibility was able to make a grand entrance to the prison systems of these societies. ‘Hard work’: prison labour was to be afflictive rather than productive, with much of it performed on treadwheels and cranks (see Figure 4.3).30 These ‘hard labour machines’ were installed in each English prison after the 1865 legislation, with the effect that ‘[prisoners are] placed on the treadwheel during the first month for six hours each day … the speed of the wheel being 32 feet per minute and five minutes rest is allowed for each 15 minutes of work … In places where for any reason a treadwheel is not available, cranks are made use of’ (Report of the Commissioners of Prisons, 1888: 10). ‘Hard beds’: the prisoners would sleep on wooden planks. ‘Hard fare’: the prison diet was to be severely restricted. The Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on Prison Discipline (1863: 498, our italics) explained that ‘cocoa and meat were unnecessary luxuries and that the functions these provisions performed could be provided by other less extravagant means: cocoa as a stimulant could be replaced by fresh air; meat as a nutrient should be replaced by other farinaceous substances and vegetable foods, so that the main elements of prison diet would consist of bread, rice, oatmeal, potatoes, milk and liquor.’ Thereafter, the Report of the Commissioners of Prisons (1878: 10) noted that the prison diet ‘has the great merit of simplicity and economy, and we have every reason to believe that it furnishes sufficient and not more than sufficient amount of food to all persons subjected to it’. Food servings then came to consist mainly of ‘stirabout’ (low quality porridge), the quantity of which was measured to the last 1/16 of a gramme,31 such was the exactitude in the degree of deprivation that was to be inflicted. In New South Wales, the diet was designed to be ‘as low as is consistent with health with due provision for exercise’ (Report of the Comptroller-General of Prisons, 1885: 2). In New Zealand, Captain Arthur Hume, the first Inspector of Prisons, introduced a new diet ‘to make imprisonment more rigorous’ (Report of the Inspector of Prisons, 1895: 3).

| Figure 4.3 | Treadwheel at HMP Kingston, Portsmouth, Hampshire. Photo: English Heritage |

Furthermore, rules regarding hygiene, dress and diet were also designed to humiliate the prisoners, to make them aware of the shamefulness and degradation to which they had been reduced, and the gulf that now existed between them and the rest of society. Their heads were thus regularly shaved and they had to wear highly stigmatic, often multi-coloured uniforms. Balfour (1901: 36) remembered how, on being received into prison, ‘there appeared a person dressed in the most extravagant garb I had ever seen outside a pantomime. It was my first view of a convict … the clothes were of a peculiar kind of brown (which I have never seen outside of a prison), profusely embellished with broad arrows. His hair was cropped so short that he was almost as closely shawn as a Chinaman. A short jacket, ill-fitting knickerbockers, black stockings striped with red leather shoes completed his appearance.’ Notwithstanding periodic reservations from some officials about these practices, the Report of the Committee of Inquiry on Prison Rules and Prison Dress (1889: 44, our italics) was of the opinion that any relaxation of the rules on uniform ‘would produce in the mind of the prisoner and of the public the impression that certain classes of offenders are exceptionally favoured’.

As these exclusionary, deterrent policies began to thread their way through the prison systems of the Anglophone societies, so the values and standards of the world outside the prison began to shrivel away within it. The prisons would increasingly be run according to their own, specifically penal values. Furthermore, those who might have had the power to challenge these intentions now found that their authority had been largely removed. First, under the provisions of the 1865 legislation, the chaplains were made subservient to uniformed chief officers, to whom they had to report, thereby signalling an end to their status in prison administration and the redemptive possibilities of the prison that they envisaged (a downgrading that matched what was happening outside the prison, as the values of industrialists and entrepreneurs became more significant than those of clerics: Perkin, 1969). They now wrote little of note in their annual reports, which were appended to the main report of the governor. In some cases, they wrote no report at all, and were given only a passing reference in the governor’s document – as at Birmingham prison, for example: ‘the services in the chapel have been thoroughly performed by the chaplain, who reports favourably on the behaviour of the prisoners’ (Report of the Commissioners of Prisons, 1879: 18). Sir Edmund Du Cane (1885: 158), Assistant Director of Prisons from 1865 and then, from 1877 to 1895, Director of the English Prison Commission, the centralized bureaucracy that had been established to ensure uniformity in prison administration, was contemptuous of them. He spoke, for example, of the ‘burlesque absurdity’ of making inmates learn sections of the Bible by heart, as had occurred at Reading prison under the Reverend John Field’s chaplaincy. Indeed, with their post-1865 change in status, they became peripheral figures around the prison, decorative but largely powerless. The embezzler Jacob Balfour (1901: 68, our italics) was greeted with the following advice from the chaplain as he began his prison sentence: ‘it’s lucky for you … that you have come just at this time. The governor who has recently left was a very severe man indeed. Things are bad enough at present, and even now I would warn you to be very careful of the warders. You are wholly in their power.’ So too, most likely, was the chaplain himself. When he and Balfour witnessed the beating of a prisoner by officers, he dolefully remarked: ‘it’s no good … there’s nothing we can do’ (Balfour, 1901: 224). In the Australian and New Zealand reports, the chaplains hardly receive any mention at all. For example, in New South Wales, the Report of the Comptroller-General of Prisons (1901: 4, our italics) states that ‘moral and religious instruction is carefully conducted by the various chaplains … it is to be regretted that unavoidable circumstances render it impracticable to increase their visits to various prisons’.

Second, the doctors now had to perform their work in accordance with the values of the prison system, rather than their Hippocratic Oaths. Their previous discretionary power to award extra rations or to supplement the prison diet had been removed by the 1865 legislation. They now had to justify, in writing, any additions to the ‘hard fare’. The Report of the Commissioners of Prisons (1878: 10) noted with approval that ‘a check may be put upon the very undesirable practice which prevailed in some prisons of supplanting the authorized diet by extra issues, which has been carried to such an extent in certain instances as virtually to set aside the authorised diet’. In addition, educational provision – of a minimal nature for most outside the prison, anyway – was even more so within it. In some English prisons – Bristol, for example – no education at all was provided (Report of the Commissioner of Prisons, 1879: 18). At Strangeways, Manchester, ‘there is one schoolmaster for 741 prisoners, and he is not a schoolmaster really, he is a warden schoolmaster’ (Report of the Departmental Committee on Prisons, 1895: 261). It was similar in the colonies. In New South Wales, it was noted that ‘at present the female prisoners receive no educational attention. Male prisoners in six gaols have fair opportunities for schooling. [But] not much is practicable in this direction, nor is much done. The teachers combine scholastic duties with those of storekeeper, clerk or some other office, and possibly attach more importance to the latter work They are not trained men and consequently labour under serious disadvantages’ (Report of the Comptroller-General of Prisons, 1896: 75, our italics). In New Zealand, Hume was of the view that ‘endeavouring to educate prisoners is a mistake … The assembling of prisoners together for the purposes of school tends to great irregularity … it stands to reason that a man who has performed his day’s allotted task of hard labour cannot possibly benefit by attending school in the evening’ (Report of the Inspector of Prisons, 1881: 20). Du Cane (1885: 79) himself was anyway of the opinion that ‘many prisoners form a class of fools whom even experience fails to teach’. The result was that, where it was provided at all, education became a privilege that had to be earned, rather than an essential component of improvement and reintegration. As the Report of the Prisoners’ Education Committee (1896: 6) noted, ‘[in England] secular education has hitherto been subservient to labour and no evidence has been adduced in favour of any alteration to this principle amongst the chaplains and schoolmasters’.

England led the way in the construction of these meticulously tailored regimes of suffering, but Australia and New Zealand pursued the same intentions, if sometimes with other means. In the former of the two colonies, a reintegrative approach to most lawbreakers had marked the earlier years of transportation (Braithwaite, 2001).32 However, as free settlement increased from the 1830s, the convict origins of the country were thought to be a shameful stain that put off investment and endangered further immigration. As Harris (1847: 223) put the matter, ‘general society cannot be said to exist in [New South Wales], particularly in the shape of public balls, reunions and concerts when you may expect to find the person on your right a murderer; him on the left a burglar’. Thereafter, a concerted effort was made to write Australia’s convict origins out of its own history (Hughes, 1987; Tsokhas, 2001; Smith, 2008). Hence, the development of a much more exclusionary penal policy based around imprisonment, rather than assigned works, as had initially been the case. Furthermore, whatever the power of ‘mateship’ to provide social cohesion outside of the prisons, there was little semblance of this within them. Prisoners embodied the convict past that all respectable Australians now wanted to forget. This not only further distanced them from the rest of society but seemed to give justification to the prison authorities to assemble their own instruments of discipline in order to ensure complete subjugation: irons, variations of wooden and leather gags, ‘spreadeaglings’ and whips.33 Meanwhile, in New Zealand, Captain Hume maintained that ‘prisoners should have their meals in their cells, and be kept quite separate, except when on the works, at exercise or at Divine service. The existing system of prisoners having their meals and spending spare time in association is most detrimental to prison discipline’ (Report of the Inspector of Prisons, 1881: 1). He then continued: ‘I would also recommend that the birch rod [that is, whip] be introduced in prisons, as it has been found in English prisons that birching, whilst being a safer punishment than flogging, at the same time, by placing the recipients on the footing of boys, has a humiliating effect and is therefore a deterrent and a valuable addition to the cat34 as a means of punishment’ (idem). In this country, the very existence of prisoners threatened its claim to be a ‘Better Britain’: their presence reduced this otherwise pristine and pure society to the level of Australia, and thereby justified and provoked the additional brutalities that were inflicted on them – as if strokes of the birch would have the effect of some sort of social cleansing and purging of the impurities they represented.

Such strategies were reflections of, rather than aberrations from, the social arrangements of these societies, in which prisoners were seen as being at the bottom of their lengthy hierarchies of moral worthiness. Du Cane (1875: 302–3) was of the opinion that they had characteristics that were ‘entirely those of the inferior races of mankind – wandering habits, utter laziness, absence of thought or provision, want of moral sense. The cunning and dirt that may be found in their physical characteristics approach those of the lower animals so that they seem to be going back to the type of what Professor Darwin calls our “arboreal ancestors”.’ Even prison re formers were repelled by them. William Tallack (1889: 216), the founding Secretary of the Howard Association, thought that prisoners were ‘not very drunken as a class, but incorrigibly lazy. Work is the one thing they most abhor; they are often too indolent to wash themselves; they prefer to be filthy; their skin in many instances almost ceases to perform its functions. Nearly all the discharge from some of their bodies is by the bowels; and when completely washed such people become sick.’ By the end of the nineteenth century, prisoners in these Anglophone societies had thus come to be thought of as a different species of humanity altogether, as if they had been excommunicated from membership of them: a way of thinking that, in turn, reinforced the need for their exclusion and justified the humiliation and deprivation that being sent to prison in these unforgiving societies had come to involve.

In the Nordic countries, the terms of separate confinement could be significantly longer than in the Anglophone: a maximum of four years in Norway, from 1848 (although reduced to two in 1900); the 1864 Swedish Penal Code prescribed a maximum of 12 months, extended to three years in 1892; in Finland, the 1889 Penal Code prescribed a minimum of four months’ separation. It was rigorously enforced: inmates could be punished for climbing on their cell window to look outside. Windowsills were inspected to see if the layers of dust had been disturbed by any such activity. While prisoners in England, under separate conditions, were allowed to dispense, in 1878, with wearing masks (to prevent recognition) on leaving their cells, this practice continued in some Swedish prisons until the 1940s.35 In these respects, separation was more central to the organization of the Nordic prisons. However, it was not intended to act as some sort of interim phase designed to break the spirit of the convict and which, once completed, would be followed by the grotesque displays of human dressage that Du Cane and his acolytes had prescribed for them in England.36 It might well do this, of course; but nevertheless in these societies, separation was understood, justified and thought of as a ‘charitable deed … the prison officials saw much to be gained from this since, as a consequence, the destructive influence of the association prisons was, as far as possible, removed’ (Almquist, 1924: 47). As such, these prisons remained true to their original purpose of ensuring that inmates were kept away from the corrupting influences of their peers and providing them with the opportunity to find redemption through self-reflection and knowledge of God(Nilsson, 1999: 312). As Crown Prince Oscar had explained (1840: 56), ‘the Philadelphian solitude has a more immediate impact on the mind, or on the intent of good or evil, and the liberated prisoner takes with him the fruit of a wholesome self-examination, and of the internal warning voice, to whose punishing severity he has been left’. In contrast to Du Cane, his Swedish counterpart Wieselgren (1895: 386) took the view that ‘solitude, interrupted only by the officials’ visits, has proved effective to induce the prisoner to introspection, open the mind to repentance, and create a need for industriousness’.