In this chapter I focus on a group of children in a classroom and the work of one teacher, Sally Bean, who taught in a class of 6–7-year-old children, in an infant school in the North of England. The school was situated on the outskirts of a town with a history of coal mining and farming. The study was ethnographic, and took place over a two year period (2005–7). I collected a wide range of data: interviews with Sally drawing on her own research notes as she reflected on her practice, my own fieldnotes, and photographs, building up a linguistic ethnography. Using this data, I developed a dense and many layered picture of the context of Sally's work, the way she enacted her beliefs and dispositions in the classroom and how the children responded to her work. I attempt to trace the enactment of her pedagogic habitus (see Grenfell 1996 and this volume) in the context of an initiative to promote creativity in the classroom. I focused on literacy events and practices, with a particular interest (mine) in the children's multimodal text-making, and seeing this process of textmaking as being ideologically situated (Grenfell Chapter 4 this volume; Pahl 2007; Street, this volume).

I begin by situating the study in a context, which was of the Creative Partnership (CP) policy (a UK initiative). The policy initiative is a background to the study but also, is the ‘field of play’ in which Sally enacted her pedagogic habitus. To make sense of this field-setting, I pay attention to those research monographs and documents that were commissioned by CP. I bring my own reflexive understanding to the dataanalysis process and the report-writing. I move between an ethnographic account of the classroom ethnography and the emerging findings from that study. By linking the enactment of CP in the classroom, to the CP policy documents and writing on creativity, to the wider field of creativity as a concept, I demonstrate how this kind of analysis is useful to unpack enactment of policy in the classroom (see also Lefstein 2008). I draw on discussions of creativity that were current at the time of doing the research (Heath and Wolf 2004; Jeffrey and Craft 2006).

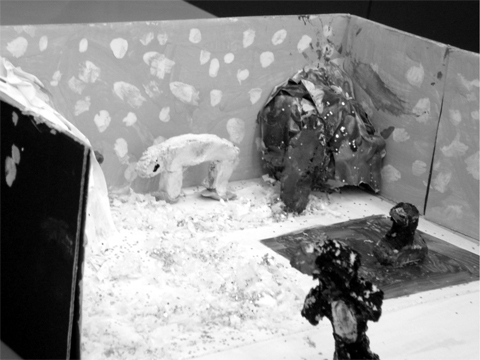

The children were engaged in making panoramic boxes, dioramas, which were natural environments such as the ocean, jungle or desert, peopled by animals. Close analysis of the classroom interaction was possible, as I carried out an in-depth study, conducted sequentially over two years. I drew on data from a wider study, also lasting two years, in which teachers, artists, pupils and parents were interviewed and a number of ethnographic observations undertaken within the school. My involvement, as a researcher, was also subject to analysis and to a form of objectification in relation to my own perceptions of the field of creativity (see Grenfell later in this volume) situating myself within the field. The class teacher also researched her own practice so that her understandings drawn from her research diary, is woven into the analysis. Part of the task of this chapter is to construct an analysis both of the relational construction of the classroom, but also to trace back the thinking I did alongside the class teacher's construction of her site, the classroom. Grenfell (in this volume and elsewhere) has consistently argued that this kind of analysis and thinking can be realised in educational research through drawing on Bourdieu's logic of practice.

I discuss the ‘field’ setting of the classroom as the place where the teacher deployed her pedagogic habitus, which was in turn shaped by the artists who worked in the school and her understanding of the ‘value’ of creativity. I then discuss the relations Sally's work and what I conceive as the world of Creative Partnerships, its policy documents, research papers and pronouncements, particularly those published between 2002 and 2005. Finally I look at a much broader level, which I consider to be the concept of ‘creativity’ as expressed over a period of time, and which has been discussed in a recent monograph by Ken Jones (2009). Bringing these all together is the task for the chapter.

Using a relational framework in a classroom ethnography context can provide a helpful lens to unpeel the way in which habitus and field interact. This can be done by looking at the language the teacher uses in the classroom but also the language the children use. By focusing closely on multimodal events and practices in the classroom in the context of recorded interaction, the arena that Creative Partnerships set up can be unravelled and dissected. Different versions of creativity were also at play which could be seen in the analysis of the classroom data.

While I, Kate, focused on how narratives could be found sedimented within multimodal texts, the teacher, Sally, focused on creativity as being about problem solving in the material world. In my case, New Literacy Studies (Street this volume) helped my analytic frame by offering the lens of events and practices. By tracing our definitions of creativity back to the literature from Creative Partnerships, and drawing on Jones (2009) who offered a number of accounts of creativity as instantiated within different traditions, it is possible to see how Creative Partnerships itself was driven by a number of discursive domains of practice.

New Literacy Studies takes as its starting point the notion of literacy as a set of events and practices (Street 1995 and this volume). Here, in this chapter I focus both on literacy as being about narrative texts within the classroom, as where children told stories that were then represented multimodally within the boxes, and as a set of practices, that is the recurrent experience of the children as they realised their visions of the boxes in a textual form. This can then be linked to box making as a situated textual practice. My account of literacy is shaped by Kress (1997, 2010) and his view of semiosis as inherently multimodal. I understand the children's meaning making to reside just in one mode, that is reading, writing and oral narration, but look across the modes to understand the meaning making of the children. In that, I share with Street (2008) a focus on multimodal events and practices. As Flewitt (2008), I take as my focus the concept of ‘multimodal literacies’ that is literacies that range across modes and are focused on meaning making in all its diversity, and then home in on the unfolding of that meaning making in the classroom.

Creative Partnerships is the UK Government's flagship creativity programme for schools and young people, which was set up in May 2002, managed by Arts Council England and funded by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) with an additional support from the then Department for Education and Skills (DfES). It was developed as a result of the ground-breaking report, from the National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education called ‘All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education’ which urged the importance of a national strategy for creative and cultural education to unlock young people's potential. Following this report, in 2000 the Qualification and Curriculum Authority commissioned a review of creativity in other countries and developed a ‘creativity’ framework. There was a hypothesis that ‘creativity’ could both enhance economic productivity and create a framework for learning that would increase pupil motivation and lead to increased literacy achievement. It was a response to the concerns from many educationalists that the National Literacy Strategy was over-prescriptive and relied on a skillsbased, ‘autonomous’ model of literacy (Street, this volume). Creative Partnerships was initially focused on particular areas of the UK, where there were considered to be higher pockets of deprivation.

The area where this study took place, Rotherham, Doncaster and Barnsley, was characterised by considerable economic disadvantage after the closure of the mining industry in South Yorkshire and the consequent loss of confidence in older industries such as steel and manufacturing. At the time of the study, 2005–7, there was some economic activity in the field of building and light industry, but at the same time, there was a concern that children's speaking and listening skills, particularly in the school where the study took place, were not being fully developed. The study itself was funded by Creative Partnerships in order to find out what was the impact of a group of artists, Heads Together, on teachers’ practices in a small infants’ school on the outskirts of a northern town in the UK.

Creative Partnerships as a scheme had wide and far reaching aims. It aimed to develop:

• the creativity of young people, raising their aspirations and achievements;

• the skills of teachers and their ability to work with creative practitioners;

• schools’ approaches to culture, creativity and partnership working; and the skills, capacity and sustainability of the creative industries.

(Creative Partnerships: Approach and Impact 2007)

At the core of the programme was the notion of artists and teachers working alongside each other to inform each other's practice. The ideologies behind the scheme were progressive and hopeful, with a focus on the unexpected and celebrating children's ability to learn and move forward using new and unusual paths. There was, however, within this, an equal interest in the role of the arts in education and ways of engaging all children in the highest forms of the arts. The Creative Partnerships initiative has been analysed by Jones (2009) as having its roots in three traditions:

• a cultural conservatism for which tradition and authority are important reference points;

• a progressivism concerned with child-centred learning;

• and a tendency whose belief that ‘culture is ordinary’ [which] led to an insistence that working-class and popular culture should be represented in the classroom.

(Jones 2009: 7)

Jones recognised that Creative Partnerships coincided with a new ‘enthusiasm for creativity’ that was accompanied by an equally enthusiastic response from the academic sector (Thompson and Hall 2008) in which the New Labour progressivism simultaneously tried to set up the National Literacy Strategy alongside a more radical, creative approach to learning.

Creative Partnerships made an effort to question its own dogmas. David Parker and Julian Sefton-Green commissioned a series of studies that critically reflected on the more enthusiastic tenets associated with creativity, and their stance has resulted in some publications that tend to scepticism, informed by such thinkers as Willis (1998) and Sutton-Smith (1997). Following the Rhetorics of Play (Sutton-Smith 1997) Sefton-Green commissioned a study on the Rhetorics of Creativity, which argued that creativity itself was really a kind of ‘rhetoric’ that could be identified with a number of different traditions (Banajai et al. 2006). Much of the Creative Partnerships funded or inspired research focused on the spaces such initiatives opened up for innovative teaching and learning. Anna Craft and Bob Jeffrey (2006) were particularly at the forefront of this academic field of ‘creative teaching and learning’. From these discussions, a view of creative learning emerged, and argued that creative learning involves:

• Relevance. Teaching that contains this is operating within a broad range of accepted social values while being attuned to pupils’ identities and cultures.

• Control of Learning Processes. The pupil is self-motivated, not governed by extrinsic factors, or purely task-oriented exercises.

• Ownership of Knowledge. The pupil is self-motivated, not governed by extrinsic factors, or purely task-oriented exercises.

• Innovation. Something new is created. A major change has taken place – a new skill mastered, new insight gained, new understanding realised, as opposed to more gradual, cumulative learning, with which it is complementary.

(Jeffrey and Craft 2006: 47)

This perspective about creative learning is echoed by Burnard et al. (2006) who also have an understanding of creative learning and teaching focusing on ways in which teachers could create the optimum conditions for creativity to happen in the classroom. In particular, they focused on learner agency as critical to creative teaching in the classroom.

Thompson and Hall (2008) identified the bringing in of ‘funds of knowledge’ (Gonzalez et al., 2005) as part of the possibilities of Creative Partnerships type teaching spaces, as opposed to the more restricted national curriculum. The possibilities offered by listening to children's funds of knowledge also opened up more difficult questions of censorship and directly, at times, clashed with priorities that the schools had set in other domains of practice.

The world of creativity has its own ‘rules’ (see Grenfell in this volume and Grenfell and Hardy 2007) and taken for granted textual practices. When consulting the literature on creativity, using the Creative Partnerships publications, many quotes were in bright, primary school type colours, in slightly larger print, as if I might be an excited creative child, rather than an academic used to the demands of article searching and reading dense black and white text. Many publications, even those that purported to be of strong academic relevance such as Heath and Wolf ’s (2004), were printed on bright yellow, thick paper, with lots of white space. ‘First Findings’, the review of creative learning from 2002–2004, had many large images, mostly photographs, of creative practitioners, alongside facts and figures represented in handwritten notes. Children's drawings and blurry impressionist images of children's faces, lit up by light and learning in new and unusual ways, were prevalent in these publications, even the more academic ones. Ken Jones’ review, while highly academic, was printed in turquoise. In terms of a multimodal analysis of these texts, they instantiated these discourses of creativity as a bright, progressive, primary school type quality, in which children's own perceptions and colour ways were at the core of the offer.

Literacy and language were a key part of the intended outcomes of the Creative Partnerships initiative. There was an effort within the sector to argue for the benefits of creativity for increasing interaction and linguistic competence, as its director, here attests,

[Creative Partnerships] is about creative education, by which I mean helping teachers teach more creatively, using creative journeys as education drivers and developing creative skills in young people. Creative education will for me achieve a range of benefits like linguistic development, more confident students, more motivated students who are more committed to education, more emotionally literate students, more curious students, imaginative kids with lots of ideas, students with an improved capacity to take intelligent risks, etc.

(Paul Collard, interview Jan 2006 quoted in Sefton-Green 2007: 3)

A focus on meaning making as well as a progressive interest in the everyday as a site for change enabled many progressive academics and educationalists to become more visible within the sector. Language and literacy were in many projects the site for this research impetus. New Literacy Studies were a helpful lens with which to look at textual practices, and to situate accounts of ‘creativity’ in relation to events and practices (see Pahl 2007).

The study was conducted drawing on ‘linguistic ethnography’ as a methodology; that is, following from Maybin (2007) and Lefstein (2008), I conducted a situated analysis of linguistic interaction in the classroom. I used tape recorders on desks to record children's meaning making and recorded, using cameras, often with the children as photographers, the multimodal texts they created. Their text-making was surrounded by observations of the teacher, Sally, and her own reflective fieldnotes and action research, together with a wider ethnographic study of the effect of the artists upon the whole school. Small-scale micro interaction, was thus placed in a wider context, and analysed in relation to the more macro concerns of the Creative Partnerships initiative. The participants of the research were as follows:

1 The artists. I spent time with the artists at their staff development day, interviewed them during and at the end of the project and watched them in action.

2 Teachers. I interviewed all the teachers at the school and then spent time discussing the research with Sally Bean, the teacher I worked with. I then involved Sally Bean in the research process itself. She also conducted her own action research project on her practice.

3 The children. I gave the children cameras and placed an audio recorder on the tables when they were making the boxes. I visited the classroom on a regular basis for the period of the box-making episodes two years consecutively.

4 The parents. I interviewed some of the parents about their children's involvement in the projects.

5 Community events, Junior school and additional follow up interviews with children and parents.

I was lucky enough to have access to the reflective materials that Sally collected as part of her own action research project in Year 1 (2006).

The data I discuss here were collected in two consecutive years. I visited the classroom in order to explore the processes and practices of the children's multimodal meaning making. As I used cameras in the research, I was able to document the way in which the boxes were made over time. I recorded interaction between children as they made the boxes and then interviewed the children at the end of the project. I also analysed my own role within the project and looked at what I brought with me into the classroom.

I analysed the data by focusing on the children's talk at the point of making the boxes and then tracing this in relation to the talk around the task and the classroom habitus. I used Wolcott's system of three columns to consider the links between description (transcript) interpretation (themes arising from the data) and analytic codes (Wolcott 1994). I placed emerging themes alongside the transcripts that I collected and placed the photographs taken by children of their boxes alongside the transcripts of what they said while they were making the boxes. I interviewed the children after they had made the boxes. I went back and traced certain linguistic themes, which were echoed across the dataset, for example, the phrase ‘we decided that’ and ‘good effect’. This required detailed linguistic analysis of both the children's transcripts and the transcripts taken of Sally's discussion. I also drew on Sally's own fieldnotes and her transcripts taken during the first year of the project. The analysis then involved looking at the policy and research documents produced by Creative Partnerships in order to situate the dataset within the thinking generated by CP at the time of writing the article.

FIGURE 6.1 Example of a box

The children were encouraged to work in small groups to create boxes that represented a particular environment, such as the Arctic, the ocean, the jungle or the desert. They were encouraged to choose their environments, research these using books or the internet, and create animals and plants to go in the environments. Shoe boxes were used to create dioramas that represented the animal habitats. As Sally wrote:

The children were given the brief: to design and make a model of an environment using a shoe box. They had spent some time, during the Spring Term, learning about living things and the way they adapt to their habitat and found out about a large variety of living things and both local and global environments.

(From SB's fieldnotes Spring 06)

Here, I focus on some of the themes that emerged from analysing the Year 1 data. These can be divided into:

• we decided on;

• a good effect;

• the unexpected outcome;

• funds of knowledge.

The first two I could link back to expressions used by Sally and were then echoed in the children's talk, and could be identified as emic concepts, while the second two concepts I found in the data, and could be seen as more etic concepts (see Bloome and Street in this volume).

When I started researching Sally's classroom, the initial focus of her work was on profiling learner agency (Burnard et al. 2006). She had found it helpful to watch the artists, Heads Together, when they worked in the school, and the way they let children decide what to do, as she described here in an interview I conducted with her:

It was a big eye opener for me, that they were so capable at deciding what they wanted to learn and what they wanted to do in that session and in that project.

(Sally Bean interview 20 March 06)

In initial discussions with the children, in the first year of the project, when I talked to the children about the boxes, I heard her voice echoed by the children in their discussions, particularly in the phrase ‘we decided on’:

TIMMY: We decided on the animals and the trees

KATE: And the trees?

TIMMY: and leaves folding down

CARL: and we tried to make it look like with the glue there, painting green.

Lefstein (2008) describes the term ‘discourse genres’ as being relatively stable ways of communicating and interacting, which serve both as resources for fashioning utterances and constraints upon the way these utterances are fashioned. When I analysed the data from Year 1, I realised that the phrase ‘we decided that’ was one Sally set store by as a discourse genre. For example, in the excerpt above, the children were echoing the rhetorical notion of ‘we decided that’, which I also recorded when listening to Sally speak in the classroom, and here in her fieldnotes of her own action research:

SB – that was a problem a pair had last year. When they came to make the rain drops. They cut out lots of little drops from clear plastic and threaded them onto cotton but they weren't happy with it in the end and they decided that they should have thought about it more.

(Sally's fieldnotes Year 1 2006)

Another kind of talk was talk that focused on the materialisation of the children's aims for what the boxes should look like, and the difference, in some cases, between what they would like to achieve, and what they did achieve. When I analysed the data from the children and from Sally, that both Sally and I collected, I could see that Sally's approach to creativity was focused on the realisation of the children's ideas within the material artefact, the shoe box. Sally singled out the group below for their ability to problem-solve in the material world and she highlighted their ability to come up with solutions to material problems. A group of girls were creating an ocean box. They talked about how it was going. This is Emma talking about her difficulties with the seaweed standing up;

EMMA: first we got a box and my partner was Sophie secondly we painted our box and then we added some things to it. My partner tried to make seaweed and we couldn't we tried everything we could think of and then teacher Mrs Bean had a bolt of lightning and she thought of something and we did it but we haven't tried it yet but I think it will work. I hope so.

(later in the discussion)

KATE: So why didn't it go well when it got to the seaweed?

SOPHIE: because we tried some see-through crunchy tissue paper, and that didn't work, we wanted it to stand up and it didn't.

(20 February 2006)

The children tried to make the seaweed stand up, but, finally, they put it at the back of the box, as they describe here:

EMMA: The seaweed's going um pretty well instead of putting it in the middle of the box we decided to put it in the back of the box. So, it's going all well but the problem with our animals is that they won't stand up. The dolphin will stand up on its front but it won't stand up right now but its standing up, but we got a dolphin an angel fish and a star fish and a crab and the crabs um … um one of its pincer's come off and we are going to try and stick it back on but its taking a bit of time, and I don't think anything going to … we have tried masking tape we have tried lots and lots of PVA glue on but its just not working.

SOPHIE: It looks like a good effect, the bubbles – all the fishes swimming here.

(20 February 2006)

Sally described what she observed from this episode in a later discussion:

I'd found them some green cellophane, it was the stuff that they wanted that they described, they just did not have the language for it, and they actually wanted the seaweed to stand up so the cellophane would have been floppy, they were finding ways of how they would have been able to strengthen cellophane, you know backing it onto paper and onto card, but they would have found that it wasn't transparent, and they toyed with all sorts of ideas, they tried a few types of paper and card and they weren't really getting the right effect, and then I just said to them, would you like me to give you an idea and I gave them some overhead projector transparency and I said they could paint on to it and mix some glue with it and it could stick and they tried it an found that it worked pretty well! It was thick enough to stand up and that idea of mixing the paint and the PVA they shared the information with other groups.

(Discussion September 2006)

FIGURE 6.2 The researcher in the classroom, Year 2 taken by children

Problem solving, difficulty and overcoming it were the focus of this group. The material world offered challenges that they wrestled with, before overcoming them with new decisions and material solutions. While Sally's perception of her role was of an enabler and her focus on the children's decisions led her work, the children's perception of her was as a powerful instigator of change (a ‘bolt of lightning’). Sally's view of the class was this:

They have done tremendously well, with the amount of external things they have brought into this project, and they have overcome a lot of problems themselves, and a lot of difficulties, whether it has been testing out materials or trying something and it not working and I have just tried to be there as a facilitator.

(SB March 2006)

A further ‘discourse genre’ as well as the phrase ‘we decided that’ was the phrase, ‘a good effect’. Sally used it in her discussion above when she describes the green cellophane and how the children were not really getting the right effect. Sophie also mentions that the look of the box is a ‘good effect’. I was interested in how this expression ‘good effect’ was linked to the material realisation of the boxes, as a sign of success, much as the expression ‘good effect’ was used in the programme ‘Changing Rooms’ which was then a current favourite on television, by which rooms were made over to the astonishment of their inhabitants. This ‘discourse genre’ which maybe has its roots in everyday creativity, could be perceived within the shards of discourse I analysed.

Many of the children followed the concept of the environmental box, and the objects inside the box were coherent with the environment (ocean, jungle, desert and Arctic). The boxes, however, also provided a space for other things to happen and for the children to enter the box as a play space. As I watched the groups, some decisions were more unusual than others;

ANDREW: about the path …

KATE: tell me about the path

TIMMY: we did it squiggly but then

ANDREW: we did it in a line but on our environment sheet it's all curvy so it's got bendy so we did it um so we did um when we looked in the (room) we thought of doing it curvy but then I thought of doing it that way, so it goes out and in

TIMMY: So you walking from there and you walk over that path – we could have put some shops in couldn't we?

(8 March 2006)

Timmy imagines himself walking over the path of his box and creates a new idea – the ‘shops’. This brought an ‘everyday’ quality to his realisation. The notion of shops in the desert had not really struck me before, and this could be described as an ‘unexpected outcome’ in the creative process (Craft 2000, 2002).

I began to see how the work with the children also referred to ‘funds of knowledge’ (Gonzalez et al. 2005) that enabled different kinds of discourses and realisations connected to everyday practices to take place. One child, Carl, who was originally from the Philippines, described his King Cobra:

CARL: We found a real cobra in the book over there.

KATE: Can you show me?

FRANCESCA: we need more red

KATE: Have you seen one on the tele?

CARL: I have seen one on the zoo. I saw a real one in my cousin's house in the Philippines.

He has got a real King Cobra in his house he has got it locked up in his cage.

He's in the Philippines.

KATE: What colours were it?

CARL: black at the top and steely and brown at the bottom.

KATE: Were you scared?

CARL: he went ssss like that.

(Taped interview 8 February 2006)

While the instruction for finding out about the animals to put in the boxes had been very much about looking on the internet and in books, the children's own ‘funds of knowledge’ (Gonzalez et al. 2005) also were brought into the field of the classroom when thinking about the qualities of the animals they were researching.

At the end of the first year of observations, I was able to identify two contrasting and competing definitions of creativity within Sally's classroom. One was about learner agency, as described by Burnard et al. (2006), in which the children were given the opportunity to decide for themselves what they did. However, the creative aspect of the classroom was also realised in the ‘unexpected outcome’ (Craft 2000, 2002), when home funds of knowledge, or different kinds of decisions, surfaced within the material quality of the boxes. The decision to have a man in the jungle, or place a King Cobra in the box, were imbued with different kinds of meanings, ones that drew on home ‘funds of knowledge’ (Gonzalez et al. 2005). These definitions, decisions, and meanings highlight the different relationships existing between myself the teacher and the pupils within the activity of the creativity project.

In Year 2, I revisited the class in the Spring Term of 2007. This was a new class of Year 2 children (aged 6–7) but with the same teacher (Sally Bean) and the same activity. I conducted the same project, visiting weekly when the children were doing their boxes and recording the process using cameras, tapes and fieldnotes. This year, Sally reported to me that she thought that the children were not as creative as last year, particularly with regard to the material quality of the boxes, in that they tended to copy the children's boxes from last year and not focus on innovative solutions to material problems. Sally focused on the same issues, that of creative problem solving in the material world:

I would like you and your partner to make your own decisions. I will help you and your partner if you get incredibly stuck but if you have not had a go at solving the problem first you need to do that, these are your boxes.

(13 March 2007 SB)

This year I found the following key themes in the analysis:

• the unexpected outcome;

• narrative connected to the boxes;

• material and narrative problem solving.

I continued to watch the children make decisions about the boxes. These were sometimes unexpected, as here:

KATE: Is this the monkey in the trees? Where did you get the ideas from?

BOYS: We just thought of it.

KATE: Whose is this here?

CHRIS: Its a man but – Jon did you do that?

JON: No

CHRIS: I did both of them – Jon did that head though.

(Taped interaction 17 April 2007)

As with the shops in the desert, in Year 1, here, the box is enlivened by having real people in it – something Sally Bean had not envisaged in her conception of the boxes as inhabited by the creatures that lived in those environments.

In the final example, three girls, Savannah, Taylor and Coral, were creating an ocean environment. I watched the process from the initial making of the box, through to the decoration of the box, until the final moment when the box was placed on the side of the classroom for display.

One of the processes I watched was the slow construction of a hill at the back of the box, using masking tape. This hill was the subject of much debate and discussion:

FIGURE 6.3 Image of a box

SAVANNAH: here we are going to paint over the masking tape so it makes it look like.

TAYLOR: We are going to put some fish in the seabed.

SAVANNAH: Yes, that's going to be – these are the seabed under here we are going to get some over there.

TAYLOR: we are going to wrap some of the dolphins under.

SAVANNAH: Yes we are going to try and get the dolphins to come in here so it looks like they are getting ready to jump up over the water!

(Taped interaction 13 March 2007)

As the hill was slowly built up, using paper, and then painted over, in a corner of the shoe box that was the box environment, the girls began to work out the hill's meaning:

SAVANNAH: We build the hill because that's going to be where every fish sleeps!

KATE: You said that about the dolphins peeking through, I like that.

SAVANNAH: Taylor, I am gonna put that shell there because it looks more nice in there I am going to bring this little light and I am going to stick it there because it can be light.

TAYLOR: Yes but the light will have to go there because it doesn't look as bright in there.

KATE: You have a little light.

SAVANNAH: We could put the dolphins we could put the dolphins.

TAYLOR: we could put the light in there because it makes it light.

SAVANNAH: Because the fish will swim into there anyway (higher pitch).

TAYLOR: No they could swim, the dolphins could be peeping through there couldn't they?

TAYLOR: Its gonna have to be ripped a bit like that.

SAVANNAH: No the dolphins sleep there, Taylor, it can't be like that.

TAYLOR: Yes that's where the dolphins sleeps.

(Discussion 13 March 2007)

The hill is a point of contestation until Taylor agrees that the hill can be a place where the dolphins sleep. This domestic role for the hill was explored further on in their discussions a couple of weeks later. As the box took shape, its making opened up a new world, in which the dolphins all acquired the role of mummies and babies and the children described a mini world in which the babies went to school, learnt and played within the environment,

SAVANNAH: That's the mummy dolphin and that's the baby dolphin!

KATE: Oh brilliant!

SAVANNAH: We put them together because the baby has to follow the mummy.

CORAL: We made it out of clay.

TAYLOR: Yeah.

KATE: Are you the ones that had a dolphin school?

FIGURE 6.4 Construction of the hill

GIRLS: yeah! A dolphin school.

CORAL: Because the mummy is going to take the baby to school.

KATE: I love this.

TAYLOR: Yes, that's right, it's really close. Because it only lives down here.

TAYLOR: We did the jellyfish, er one's the sister, one's the brother, one's the baby and one's the mum.

CORAL: that's the baby.

TAYLOR: yeah and that's the sister and that's the brother and that's the other big sister.

(Discussion 17 April 2007)

In this sequence of talk, which went on for some time, and takes up over two pages, as a transcription, the girls describe how the school is made up of a number of children, in an actively imagined space, where children learn using shells for pencils and live an ordered ‘play school’ environment:

SAVANNAH: The daddy's died.

TAYLOR: We made some children because there is no point making the school if there aint gonna be no children to go in.

(17 April 2007)

The children used the box to re-create their space, the space of the classroom and they focused on how the ‘space of school’ could be recreated using the ‘space of the ocean’ at the same time:

SAVANNAH: We did some shells so then they can pretend they are paper and pencils.

TAYLOR: So they can write on it.

CORAL: We put big shells and little shells because the shells are going to move.

TAYLOR: The big shells are for writing on and the little ones are for the pencils.

KATE: For the pencils?

CORAL: There are 24 shells on there (starts counting 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13).

(17 April 2007)

These extracts again highlight the relationship underpinning the structures set up between the child and the artistic object as mediated in a particular structural (relational) context. The narrative talk takes in sleeping dolphins, a dolphin school, a space where the babies stay at home, where the daddy dies and where the shells are used for writing. The school story that is enacted through the box has its origins in everyday life as well as in school experience. The narrative text occupies a hybrid space, across the domains of home and school and while the event (the talk spans both domains) the box also contains a number of references to home practices, such as sleeping and babies, as well as schooled practices such as paper and pencils – literacy materials.

FIGURE 6.5 Finished box

The boxes were used as spaces where both material dilemmas and narrative concerns were raised, and represented, across the collaborative structures that Sally set up. In the case of the school it was the issue of the rock that became a door that determined the outcome, that of the environment as a dolphin school.

Taylor: We did the school because um we just wanted to make, well we decided that we wanted it to be a rock, but then we changed us mind to put it to a school because there's a door.

(17 April 2007)

The decision to make the rock into a door for the dolphins to emerge from then created the imaginary space of the dolphin school. Taylor articulates the reason for the school being located within the material world (we changed us mind because there is a door). In the earlier excerpt of talk, where there was a discussion about the dolphins sleeping, it was clear that the rip in the hill transformed the box both into a home (with a bedroom for sleeping) and a school (where you could line up). The materiality worked together with the narrative to open up new possibilities for meaning making.

However, while the focus of the teacher, Sally Bean, was on creativity as located in the material problem solving, I was interested in the narrative talk of the children, as they turned their boxes into an imaginary school, as well as an imaginary home. While Sally was focused on creativity as being about learner agency (‘we decided that’) and about the importance of craft activities as a space for this learner agency to be deployed, I was interested in the ‘ordinary’ culture of the children, in the world of the dolphin school, where the babies stay at home, and the siblings are described and the baby follows the mummy on the trip to school. Everyday life is brought to life in this sequence of talk which I found, like Steadman's girls’ talk in The Tidy House (1983), to be an enactment of everyday life in a small Yorkshire town, its features of siblings, and walking to and from school and playing school. Culture, as ‘ordinary’ (Williams 1989) and creativity as being about the mix of everyday life with schooled symbolic repertoires could be linked to Willis’ concept of the symbolic creativity that children bring to meaning making in everyday life (Willis 1998).

This data was collected at the end of a Creative Partnerships project and focused on one teacher, not on the artists’ role in the school. However, reflecting on the data, it can be linked back to Heads Together, (the artists) and their belief in children as agents in their own meaning making, which, in turn, can be traced back to the work of Burnard et al. (2006) in seeing creativity as being, above all, about profiling learner agency. Creativity as being a craft activity, an idea implicit in Sally's teaching and instantiated within the work of many creative practitioners who focused on the material as a space for children's agency to be realised (see Heath and Wolf 2004).

I was, by contrast, interested in the surfacing of the children's ‘funds of knowledge’ across the two datasets, and found much to perplex me in the data. Why was there a man in the desert? Why was the King Cobra so special to Carl? Children drew on local knowledge to flesh out information they had gathered from the internet about their environments. Many children drew on trips to the seaside to articulate how they saw their ocean environments. Everyday life seeped into the making of the boxes. I, therefore, as a researcher, was following the work of Willis (1998) and Williams (1989) in looking at everyday knowledge and a mixing of hybrid genres of meaning making surfacing within this activity. Sally was less interested in the narratives that emerged from the box making but on the processes and practices as described by the children as they made the boxes.

Sally's own location of her practice fits well both with the background of many of the children who attended the school, whose grandparents were miners or farmers, and for whom craft would be important, and also with the focus of the artists, who liked to create new kinds of texts from the children's drawings. As she said of herself,

My personal interest in creativity started at an early age and has continued into my professional career as a teacher. Art and Design and Design Technology were always my favourite subjects at school and I continued with this when I took A-level Art and then Art as my specialist subject during my degree.

(From Sally's own personal reflection March 2006)

In Pahl and Rowsell (2010) I wrote of my own personal interest in this field:

I (Kate) learned from Raymond Williams (1958, 1989) that texts are part of culture, that they sit within social contexts that themselves are subject to deep and sometimes unexpressed structures of feeling.

(Pahl and Rowsell 2010)

These accounts of creativity I then linked to the analysis of the policy documents from Creative Partnerships at the time of doing the project.

What can we gain from bringing in a Bourdieusian analysis to this? At one level, the pedagogic habitus, of letting in new experiences and allowing learner agency can be seen in the texts and practices that occurred in the classroom, such as the dolphin school, the men in the desert and the cobra that hissed at the boy. Sally's pedagogic habitus could be seen instantiated within the ability of the children to figure out how to make seaweed stand up using transparent plastic and glue mixed with paint. These small-scale multimodal events and practices, unearthed during classroom ethnography, could remain at that level. However, what happens if this analysis is expanded?

My version of creativity (the girls’ narrative talk, echoing the everyday as culture) as opposed to Sally's (creative problem solving in the material world) could be seen within the choices of data we chose to discuss (me) and in the focus for her teaching and discussion (Sally). Jones argues that, ‘Much current thinking about creative learning has an impulse towards the social and the cultural’ (Jones 2009: 77). He cites authors such as Cochrane, Craft and Jeffrey who talk about ‘surfacing the learner's experience’ and the focus by Cochrane on being close to young people's experience. He also identifies this space as ‘lonely’ – as being not connected enough to the past, and other studies of working-class life and experience. Other studies, such as Steadman (1983) and Reay and Lucey (2000) on working-class children's experience of space and place, are important place to locate the narrative texts that I found in the classroom ethnography. Other studies, such as Sennett's (2008) book on craft, concur with Sally's view of creativity as a space of practice, where autonomy is exercised by problem solving in a material sense.

Sally also expressed the belief that letting children lead projects was a more effective way of teaching and learning to take place:

Giving the children a sense of ownership towards their learning really impacted on my teaching and, as we have continued to develop our topics, projects and curriculum, I try to make projects more children-led than teacher-led.

Sally felt that the first year (Year 1) the children were able to instantiate her beliefs in autonomy and problem solving in craft forms through the meaning making, and she reflected that:

Now I feel that much more of my personal interest in Art and my personality can be reflected through my teaching.

(Personal reflection March 2006)

In Year 2, however, she felt frustrated that the children were not quite as focused as last year;

This class don't seem to think logically! I have just been watching [not clear] who is pretty intelligent and she is painting a small animal with a huge brush and she is reaching across the table!

Sally's ‘logic of practice’, therefore was focused on how the children responded to the material conditions of their meaning making. I was interested in the unfolding stories that arose as the children made the boxes. Sally's pedagogic habitus could be traced back to her interest in art and craft and design technology as well as her experience of the artists, Heads Together. My objectified reflexivity was visible in my use of Williams (1989), and Steadman (1983) and narratives as instantiated within the talk of the children.

As noted in this chapter and elsewhere in the book, Bourdieu's ‘logic of practice’ needs to be understood as relational above all. Having a relational consideration of the data deepened my understanding of how Sally and I were enacting our views of creativity in our research and in the analytic framing we brought to the field of play. It was helpful to have Ken Jones’ account of the background history of creativity (Jones 2009) and in particular, his account of culture as situated with the domain of everyday working-class experience. I could then join up my thinking with work on mining communities (Warwick and Littlejohn 1992) and rural literacies (Brooke 2003) with this dataset. I am not sure which ‘view’ of creativity, had most currency. While I have since written about the girls’ talk (Pahl 2009) I am not sure my writing has changed policy. Creativity as material problem solving, in the focus on glue and sticking, on making things into ‘a good effect’ however, I could see located in another domain of practice, the ‘Changing Rooms’ culture of the television makeover series, (in which ordinary people's homes were also transformed by extensive cutting and sticking) which was, perhaps more powerful in the world outside Creative Partnerships. Writing this chapter has made me reflect on the things I find in the data, and what teachers see in data, and led me to a consideration of the role of the pedagogic habitus as artists and teachers try to find a common language across different domains of practice.

1 With thanks to Sally Bean for helping me understand what she was doing.