The nature of clitics

This chapter offers an in-depth analysis of clitic morphology, clitic placement, surface constraints, and the reanalysis processes affecting clitics. A case in point is the spread of syncretism in the clitic paradigm of Latin American Spanish, which shows an almost complete merger of the second and third person. Third person clitics display a singular concentration of person, number and gender features, split into dative and accusative cases, marking indirect and direct objects, respectively. I propose a fine-grained distinction between first and second person clitics and third person indirect and direct object clitics on the one hand, and the invariant third person clitic lo, including with some restrictions the gender-specifying clitic la, on the other. In chapter four some of these changes will be treated as grammaticalization and linked to topicality and secondary topic marking.

2.1Background

An intriguing aspect of the grammar of Romance clitics is their morphology, especially their status as either independent (free) syntactic forms subcategorized by the verb, or inflectional affixes (agreement morphology), a debate that dates back to Sapir (1921: chapter 5). I base the following discussion on the generally accepted assumption that affixes are bound elements (which cannot occur in isolation), rather than independent words (which are free and syntactically active/visible). The morphology-syntax mismatch inherent in the concept of a clitic means that neither the ‘free’ category nor the ‘independent’ category can be defined in a clear-cut manner, since the criteria used are gradual and not absolute. A further difficulty is that the categories are defined in negative terms, as will be shown in Kayne’s test for clitichood below. Clitics, in short, are notoriously difficult to define and classify: they seem to live and move between the interfaces of phonology, morphology, syntax and discourse. The morphological categorization of Spanish pronominal third person clitics as affix or word is affected by all these uncertainties.

Van Riemsdijk’s introduction to clitic syntax in European Languages (1999) exposes the complex nature of clitic phenomena. Spencer and Luís (2012: 328) offer a broad perspective on what they call ‘linguistic beasts’ as well as analysis of clitic-related phenomena across a wide range of languages in a variety of theoretical frameworks. They raise the question whether ‘clitic’ as a discrete category even exists, but find it useful as an umbrella term for elements that show the phonological properties of affixes and distribution as function words. Everett (1996) goes even further and denies the existence of clitics as a morphosyntactic category altogether.20

In view of these debates about the nature of clitics it is worthwhile to review the conclusions reached within different theoretical frameworks. In generative theories, the treatment of clitics is either via a movement approach or a base generation approach. The first well-elaborated movement analysis was Kayne (1975) for French. In a Government and Binding (GB) framework he advanced the view that clitics satisfy the subcategorization requirements of their verbal host by moving from argument position into their respective clitic position – either proclitic or enclitic – obeying surface structure constraints and filters (Perlmutter 1971), and leaving behind a trace in the source position. The movement analysis works well for French (and for Italian) because clitics and their arguments are in complementary distribution. Co-occurrence of clitics and their arguments in Spanish and Romanian, however, makes a movement analysis problematic.

Base generation analyses (Borer 1983, 1986; Jaeggli 1982; Lyons 1990; Suñer 1988) treat clitics as agreement markers coindexed with a small pronoun in argument position; the clitic is base-generated in its actual surface structure. In clitic doubling the argument position can be filled by the referential noun phrase. This analysis accommodates the double function of clitics as pronominal clitics and agreement markers, functions which have in common attachment to the verb, but which differ in two important respects:

- Obligatory with or without overt and non-overt arguments (agreement markers).

- Show constraints on co-occurrence with overt arguments and can be subject to clitic climbing (pronominal clitics).

As discussed in chapter one, the constraint-based theory of Lexical-Functional Grammar rejects structural transformation including movement and scrambling. Therefore, only non-movement analyses, such as base generation, are compatible with this theory.

Zwicky (1977) coined the terms special clitics and simple clitics to draw a distinction based on syntactic properties. Simple clitics have two forms, a phonologically reduced and a full form, that occur in the same position and perform the same role. English, for example, has reduced forms ‘s’ or ‘d’ that can be used instead of the full form is/has, would/have (Zwicky 1985: 295). Special clitics have no alternative form and their special character is related to syntax and semantics. They occur in special positions, for example in second position in Slavic languages, or in Romance languages where they can attach to a verb, and in Warlpiri where they can attach to the tense marker auxiliary either as special clitics or as affixes. According to these criteria, Spanish pronominal clitics are normally categorized as special clitics. Zwicky (1985: 289) claims that “clitics are more marked than either inflectional affixes or independent syntactic units (i.e. words)” based on the ‘Zwicky and Pullum criterion’ (Zwicky and Pullum 1983), which is a series of tests that allows differentiation between clitics, affixes and words.21

Proposals for regarding clitics as inflectional affixes come from linguists working in a variety of formal frameworks. For example, in a Principles and Parameters framework, Zagona (1988: 129, fn12) analyzes Spanish clitics as “inflectional (person, number and gender) spellout of the Case feature of the head” as shown in (16), where the the clitic agrees with the gender and number feature of the lexical head ‘Juan’.

A similar analysis for French is Miller’s (1992) who qualifies French clitics as part of the morphological inflection of the verb.

The view that Romance direct object clitics are independent syntactic elements adjoined to functional heads is taken by Kayne (1989; 1990) and Uriagereka (1995), with Torres Cacoullos (2002) principally discussing subject clitics.

Other authors focus on typology in a minimalist framework, for instance, Franks and Holloway King (2000) provide a very detailed analysis of Slavic clitics; or, on Romance interfaces such as Monachesi (2005), an extension from work on Italian clitics in Monachesi (1999) in Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar, a unification-based framework closely related to Lexical-Functional Grammar. Using various theoretical frameworks, Miller and Monachesi (2003) offer a very comprehensive discussion of Romance clitics, including object, subject and adverbial clitics. Work on morphology and clitic placement can be found in Halpern (1995) and Halpern and Zwicky (1996). More recently combined with Optimality Theory, Anderson (2005) provides a very comprehensive discussion of simple and special clitics at the prosody-syntax interface. The collection of papers in the edited volume Challenging clitics (Meklenborg Salvesen and Helland 2013) presents research on a wide range of clitic-related phenomena in a variety of theoretical approaches and extends it to lesser studied languages and Romance varieties (Asturian and Cajun French). This is to name only some influential works; the list is by no means exhaustive.

In comparison to other frameworks, relatively little work on clitics is available in Lexical-Functional Grammar and linguists often resort to ‘I know one when I see one’ (Holloway King 2005). However, various accounts taking different points of view have been proposed for several languages. For example, second position clitics (Wackernagel clitics) have been analyzed for Warlpiri by Simpson (1991), for Tagalog by Kroeger (1993), and for English and Serbo-Croatian by O’Connor (2002, 2004) with the last two focusing on the interaction of prosody and discourse structure. Hindi discourse clitics have been described by Sharma (2003), Wescoat (2002, 2005) provides an analysis of morphology-syntax mismatches for English auxiliary contraction with lexical sharing. Bögel, Butt and Sulger (2008) explore the morphology-syntax interface in the Urdu ezafe construction. See Wescoat (2009) for person marking, and lexical integrity in Udi, and Dione (2013) for clitic surface position and lexical integrity in Wolof. More recent work concentrates on clitic syntax and prosody and modelling resulting interfaces (Bögel 2010; Bögel, Butt, Kaplan, Holloway King and Maxwell III 2009, 2010) and on the prosody-semantics interface (Dalrymple and Mycock 2011). See Lowe (2011, 2014, 2015) for diachronic work on prosody and accented clitics in Rgvedic Sanskrit and prosodic constraints in Ancient Greek and Pashto in Optimality Theory.

Syntactic analyses for Romance clitics have been proposed for French by Grimshaw (1982a), and for Spanish spurious se22 (which is the use of se for le in clitic cluster, e.g. le lo → se lo) by Grimshaw (2001); for Italian and French by Schwarze (2001).

2.2Romance clitichood: bound or free forms

Clitic systems across the Romance languages are quite comparable and uniform, with the notable exception of a lack of locative clitics in the Iberian subgroup Spanish and Portuguese (Spencer and Luís 2012: 34).

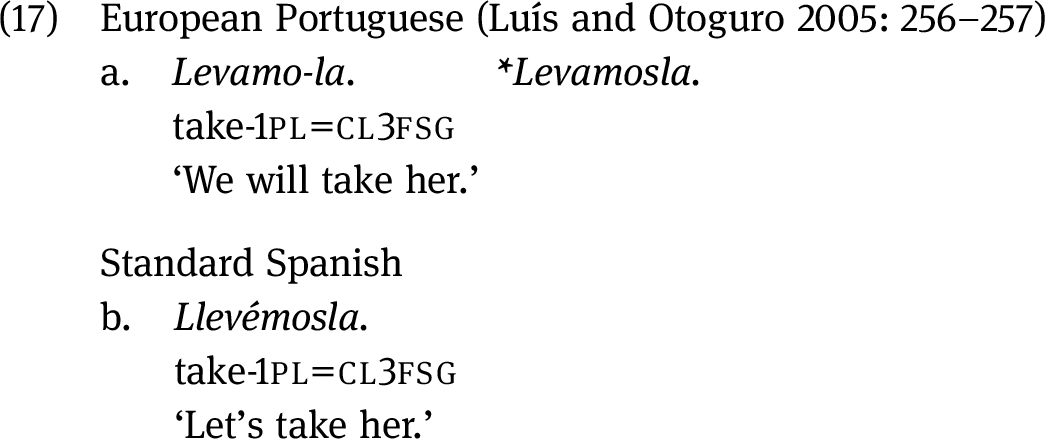

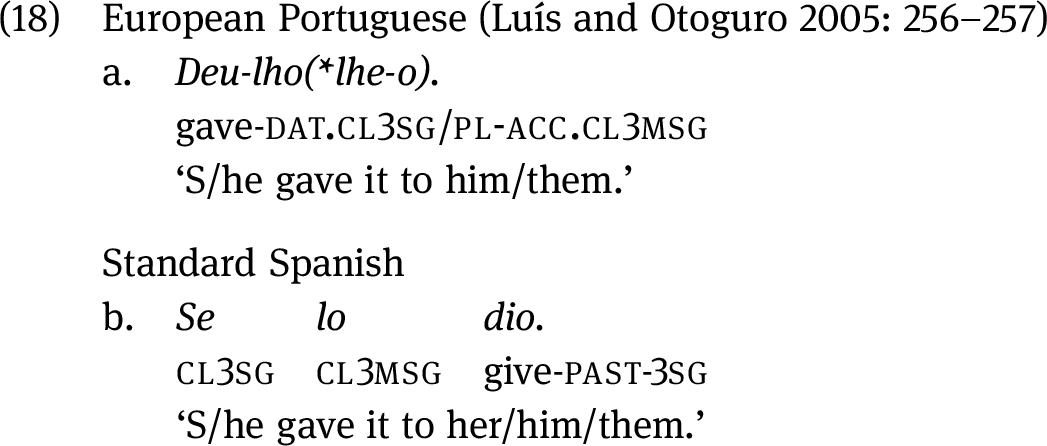

European Portuguese (EP) displays a mixed clitic system, in many ways similar to Spanish, but showing important differences. In Luís and Otoguro (2005) proclitics are treated as ‘phrasal’ affixes that are syntactically independent; enclitics are seen as stem-level affixes producing an inflectional string. The mixed clitic system in Spanish patterns in a very similar way to European Portuguese, with three significant differences. Firstly, Spanish enclitics in (17b) do not trigger stem allomorphy23 as EP enclitics in (17a) or clitic allomorphy (18a).24

However, they share person and case syncretism as demonstrated in (18). For Spanish syncretism see Tables 2, 3 and 4 in section 2.1.1 below.

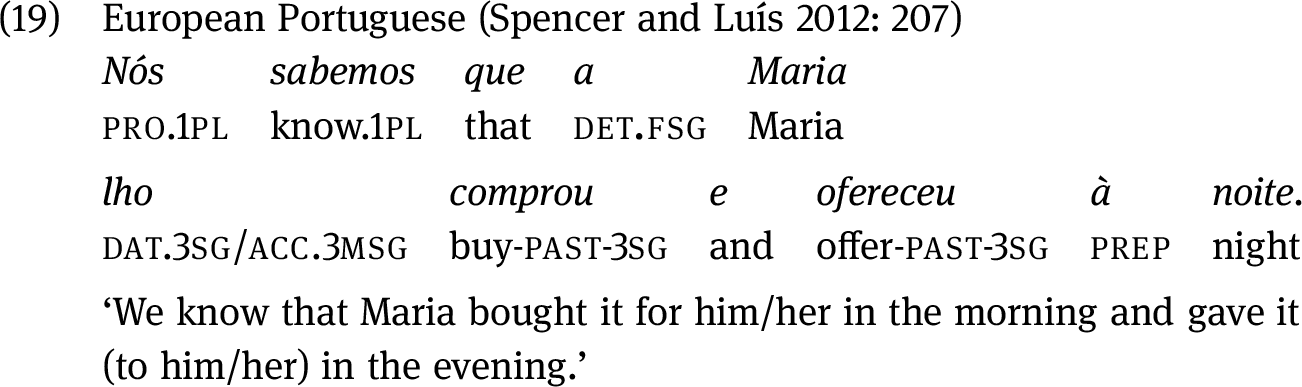

The second remarkable difference is that European Portuguese proclitics can take scope over a coordinated phrase; Portuguese seems to be unique in this among the Romance languages. Note the proclitic lho is a portmanteau cluster.

Thirdly, proclitics in European Portuguese can be separated from their host verb by lexical items.25 Klavans (1985) argues that Romance clitics are an “odd sort of affix” rather than an “odd sort of clitic” because of their placement as a lexical head with a verbal host (Luis and Spencer 2012: 47).

Enclitics are stem-level inflectional affixes morphologically attached to a verbal host (Andrews 1990; Spencer and Luís 2012).

The mismatch between the normally bound status and this looser rule creates problems for a Lexical-Functional Grammar treatment where the representation of phrasal affixes or special clitics on c-structure puts the lexical integrity principle26 at risk (Bresnan 2001c).

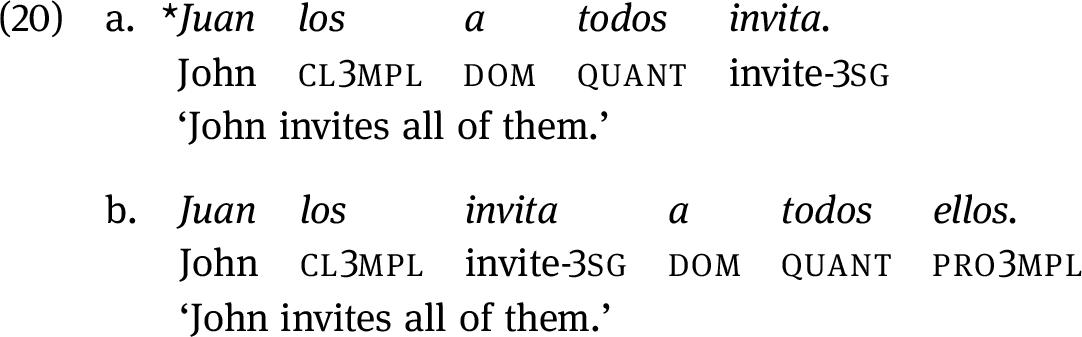

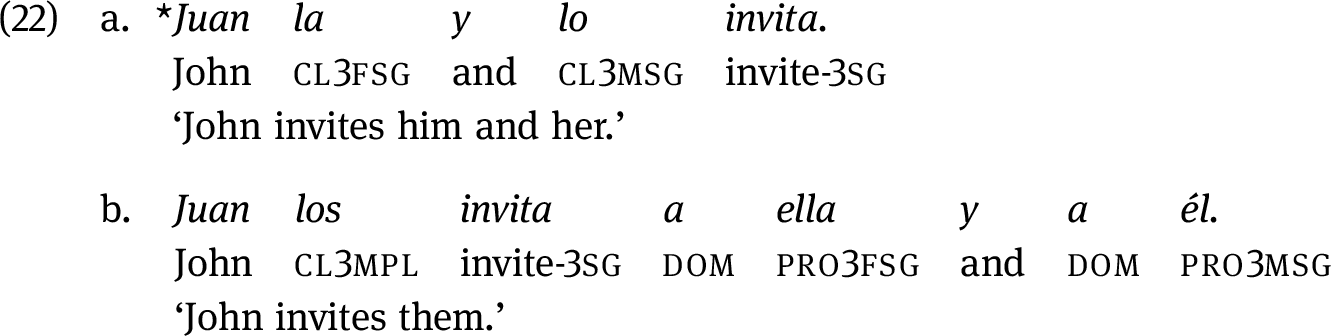

Based on a series of criteria, Kayne (1975: 81) argues that French clitics are “closely bound” to the verb and as such that they cannot be “attached as a sister to the verb”, however they form a constituent with the verb.27 Examples (20) to (24) use some of these criteria to illustrate the Spanish opposition of strong versus clitic pronouns.

A clitic cannot be modified (20a) but a strong pronoun can be (20b).

A clitic cannot be contrastively stressed (topicalized) (21a) but a strong pronoun can as shown in (21b).

A clitic cannot be conjoined (22a) but strong pronouns (22b) can be conjoined.

A clitic cannot appear in isolation, it needs its verbal host and cannot appear postverbally (23a), but a strong pronoun can (23b).

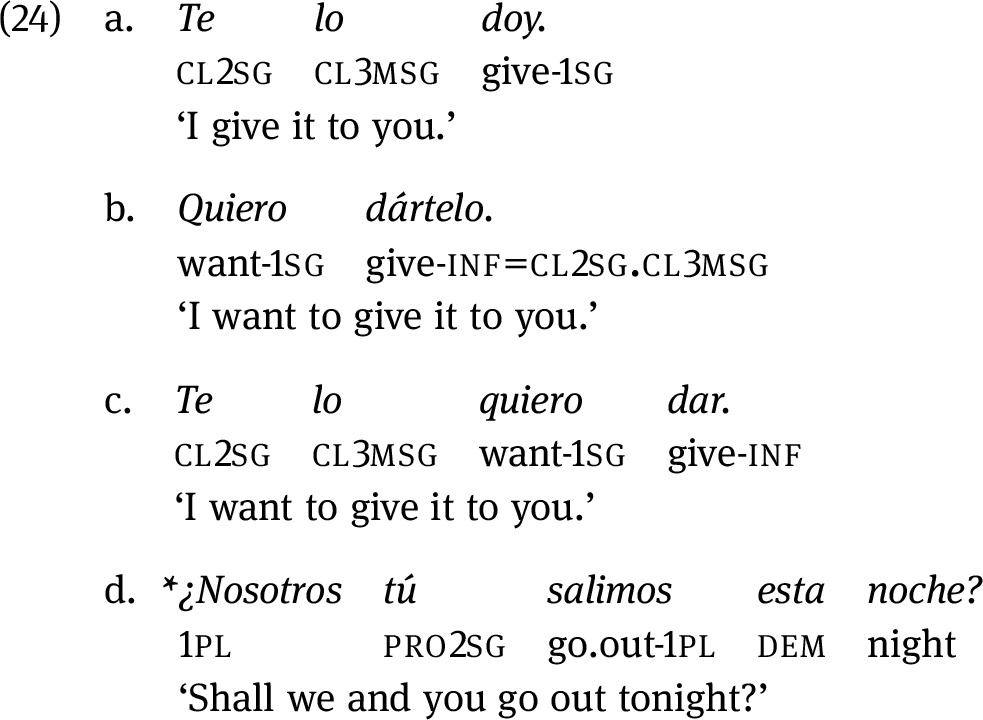

A final point to be made is that clitics can appear together in so-called clitic clusters, as proclitics (24a) and enclitics (24b) attached to the nonfinite verb in an instance of clitic climbing. In complex predicates clitic climbing is an optional variant of proclitic placement as in (24c). Clitics when occurring in clusters depend on specific alignment constraints which will be discussed in section 2.5. Strong pronouns can never co-occur in this way (24d).

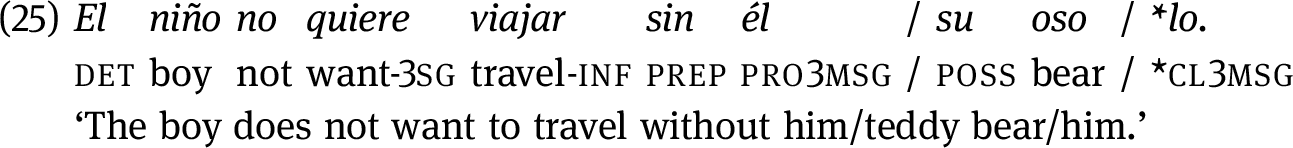

A further distinction between clitics and pronouns arises from locality restrictions, namely the inability of clitics to occur as the object of a preposition. This is a well-attested crosslinguistic restriction for object clitics.28 Consider (25) where a prepositional construction is possible with a strong pronoun and with a determiner phrase but not with a clitic.

To summarize the differences between clitics and strong pronouns, as shown by the examples above, there are four important distinctions. Clitic pronouns can neither be modified ((20) and (21)) nor coordinated (22), and they are subject to strict locality constraints in relation to their verbal host ((23) and (24)); finally, they cannot be the object of a prepositiona (25). For the present we will distinguish between two classes of pronouns for Spanish, strong pronouns and clitics.

Most proposals for the typological classification of Spanish pronouns and clitics adopt Cardinaletti and Starke (1996, 1999), who divide pronouns into a syntactically non-deficient class and a syntactically deficient class. The tripartite division shown in the hierarchy of (26) is originally based on the binary division of syntactic clitichood into strong pronouns and clitic (Kayne 1975).

| (26) | PRO > WEAK > CL |

The division in (26) is based on the phrase structural properties of each pronominal category. In Cardinaletti and Starke (1996: 36) clitics are deficient pronouns (X0s). Strong pronouns (PRO) are non-deficient, full noun phrases (XPs); weak pronouns are deficient noun phrases with exponents such as Italian loro (Egerland 2005) and German es (Cardinaletti and Starke 1996, 1999). The intermediate category formed by weak pronouns shares properties with clitics such as non-modification and non-coordination. Weak pronouns in Romance represent a true transition between lexical and syntactic status, exemplified best by the hybrid morphosyntactic status of European Portuguese clitics. Unlike Spanish clitics, Portuguese clitics are phrasal and stem-level affixes, clitic clusters undergo stem allomorphy and, unique to Romance languages, clitic clusters can take scope over a coordinated phrase (Spencer and Luís 2012). In Spanish, the weak pronouns disappeared early; there is no written evidence to document the change from weak to clitic, as this happened very early in the transition from Classical Latin to Medieval Romance (Egerland 2005). Also, a distinction into weak and clitic is not warranted, due to their uniform syntactic properties: they cannot be modified, conjoined, topicalized, nor appear in isolation.

The PRO in (26) represents the strong, stressed personal pronouns; they are theta-role bearing arguments. Weak pronouns in Spanish do not exist any longer as already mentioned before. Clitics function as agreement markers when they co-occur with an object argument (e.g. in clitic doubling); without an argument, they can also be theta-role bearing arguments, with optionality of the alternate functions specified in lexical entries.29 Both series are morphologically distinct. Clitics, whether proclitics or enclitics, are phonologically dependent on the verb as their syntactic host and cannot occupy the canonical postverbal object position.

Above, I have shown the complexity of morphological classification of the dative and accusative clitics in Spanish. The next section introduces Spanish third person clitics with special reference to their unique properties in Latin American Spanish.

2.3Dative clitic vs. accusative clitic

The view that case-marked elements such as third person clitics are deictic and anaphoric agreement affixes is strongly supported by the following facts. An important similarity shared by pronouns and demonstratives – and which justifies grouping them together as opposed to first and second person – is that they are presumed insufficient to identify a referent based on their descriptive content alone, requiring support from the linguistic or extra-linguistic context. Whereas modern Spanish first and second person clitics originated from personal pronouns, third person clitics originated from the Latin demonstratives (27), preserving the Latin case features gender, case and reflexivity.

| (27) | third person masculine | lo < illum |

| third person feminine | la < illam |

This general, widespread and cross-linguistically attested assumption is particularly evident in third person Spanish clitics and accounts for their special behaviour as will be shown in section 2.4. Many languages use a double referential system: pronouns for first and second person, and deictics such as demonstratives for third person. The third-person demonstrative pronouns usually have two forms, one referring to human and another to non-human referents, the latter being also open to human referents as, for example, in most indigenous Australian languages (Andrews 2007). This is also the case of Spanish third person clitic pronouns.

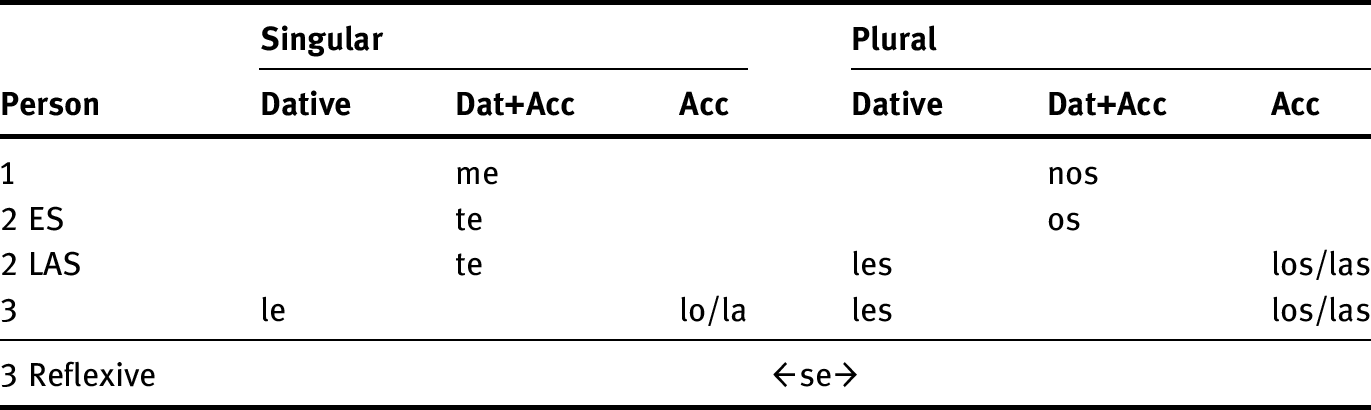

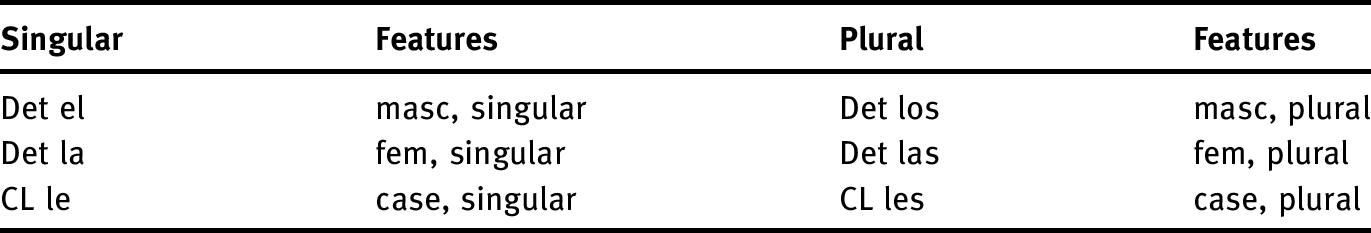

Table 2.1 illustrates the paradigms for the unstressed accusative and dative clitics which can be doubled but never replaced by strong third person pronouns (stressed, non-reflexive).

Table 2.1: Accusative and dative clitic pronouns in Spanish

Case-syncretism for accusative and dative forms is complete for the first and second person singular and plural which show perfect agreement. The third person paradigm distinguishes between the dative with case and number features, and the gender and number specifying accusative.30 The repetition of the second person paradigm, highlighted in grey, is representative for practically all Latin American Spanish (LAS) varieties where the European Spanish (ES) second person plural forms os have been replaced by the third person forms.31 Note the spread of syncretism due to a complete merger of second and third person plural forms in Latin American Spanish.

Table 2.2: Accusative and dative reflexive pronouns in Latin American Spanish

Accusative and dative reflexive forms as they appear in Table 2.2 representing the Latin American Spanish paradigm, show an even more simplified highly syncretic paradigm with se representing half of the forms, assuming the elsewhere position.32

Tables 2.1 and 2.2 are combined in Table 2.3 to give a comprehensive picture of clitic syncretism in Latin American Spanish.

Table 2.3: Syncretism in the Spanish clitic paradigm

As Table 2.3 shows, forms for the first person singular object clitics are fully syncretic. They are underspecified for gender, unmarked for case but marked for person, and as such they can be used with both objects indiscriminately. Syncretism in the second person paradigm remains in European Spanish (ES), with os functioning as the sole form. Syncretism extends to the second person plural paradigm in Latin American Spanish where os is replaced by the third person forms. In the third person paradigm, which displays specific forms for the dative (marked for case and number), and for the accusative (marked for gender and number) some syncretism is operative since there is no gender distinction.

The reflexive se in the last row of Table 2.3 is a fully syncretic marker, ‘without explicit reference (gender and number)’ (Pescarini 2005: 253), covering as a portmanteau morpheme third person singular and plural, second person plural reflexive pronouns, impersonal se, passive se and spurious se. Zagona (2002: 17) notes that impersonal se is the only true subject clitic in Spanish and can be replaced by ‘one’.

The spread of syncretism in Latin American Spanish causes problems because of the loss of consistency of expression (Spencer and Luís 2012:5), since syncretism breaks the one-to-one correspondence between form and function/meaning. However, the form itself remains consistent in all environments. I will discuss this further in section 2.5, in conjunction with the Person-Case constraint in clitic clusters.

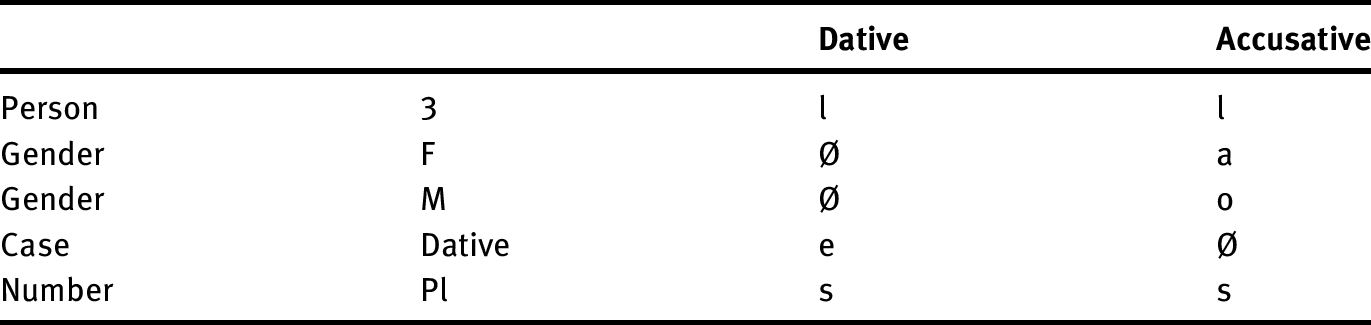

The clitic forms can be decomposed ino features as shown in Table 2.4,33 with morphological features corresponding to their phonological segment.

Table 2.4: Clitic morphology and phonology

The dative /e/ is considered the marked case value, the accusative is unmarked for case but marked for gender. The feminine /a/, masculine /o/ and plural /s/ features are all present as exponents of declension classes, displaying the exact same features as in the morphological inventory of nouns and adjectives. The accusative clitics are the only ones still reflecting the gender distinction.

Greenberg (1966) noted that if nouns of a language display gender, then pronouns will too. In Spanish, all third person strong pronouns show gender distinction. In this respect the accusative clitic is more like a strong pronoun than the dative clitic. This leads to the conclusion that all features of the paradigms are morphologically marked a shown in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Feature representation of third person clitic pronouns

Feminine gender and dative case are the marked values in the paradigm, considered so because of the narrow and specific range of application of the feminine gender. Lo as exponent of neuter and masculine genders is the unmarked value, the default, as will be shown below in section 2.4.

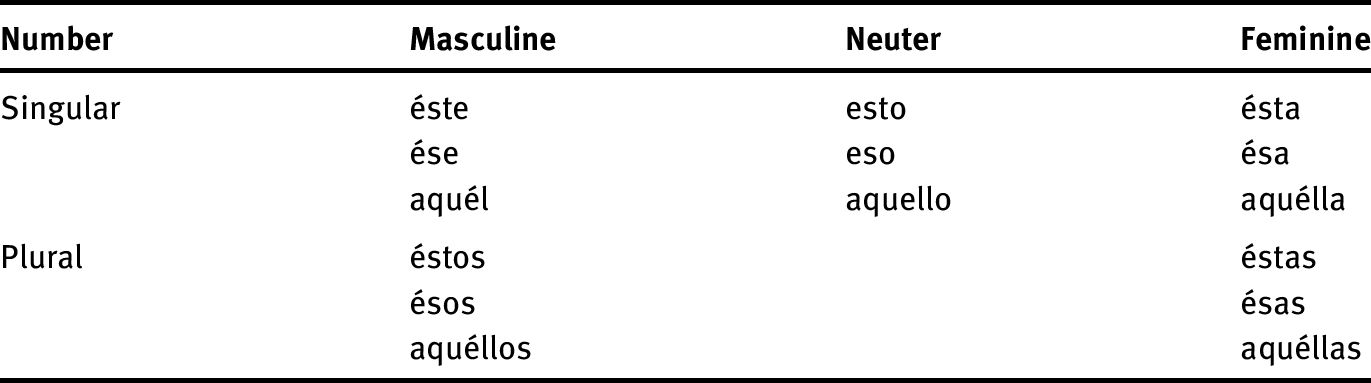

In a slightly different analysis Pescarini (2005: 250) treats the thematic vowel /e/ as the elsewhere exponent “inserted in the gender slot when [gender] is neutralized”. This view does not clash with the present assumptions and resulting analysis. On the contrary, as shown in Table 2.6, it is supported by the same features of the Spanish three-way distance specifying demonstratives.

Table 2.6: Demonstratives and elsewhere position of /e/

Note that, unlike the nominal category, the demonstrative forms are traditionally described as having neuter gender, which is a last remnant of the Latin neuter. However, these singular forms only refer to propositional content and cannot be combined, two properties they share with neuter lo.

Another approach is given in Harris (1994) (as read in Pescarini (2005)) and in Harris (1995), where the initial /l/ exponent is analyzed as a syncretic case marker for accusative and dative and /o, a, e/ as class markers.34 Parallel to double object constructions – where overt realization of the syncretic case marker a is restricted to the referential argument – the same constraint would apply to clitic clusters. However, that would rule out clusters of the type me le, se le, which clearly exist in Spanish.

Evidence from other Romance languages, as well as the genesis of modern person three clitics from the Latin demonstrative ille, provide further clues for /l/ to be rather a person exponent than case exponent. Also, /l/ appears in the third person strong pronouns él and ella. Moreover, note the almost complete structural overlap between the definite articles and direct object pronouns in Table 2.7. Both are gender-bearing and the only divergence is in the masculine, singular lo. Strong pronouns, definite determiners, and accusative clitics share the gender features masculine and feminine; the accusative clitic lo is the only one to combine masculine and neuter.

Table 2.7: Strong pronouns, definite determiners and accusative clitics

The dative clitic in Table 2.8 on the other hand, only shares the number feature /s/ and the exponent /l/ with the determiner paradigm. The occurrence of /e/ in demonstratives (Table 2.6), in personal pronouns (él, ella), and in the masculine, singular definite article (el) further supports the elsewhere position of /e/.

Table 2.8: Definite determiners and dative clitic

In sum, I have shown in this section that the second person clitic paradigm in Latin American Spanish displays two new phenomena in the plural paradigm. Firstly, the loss of the syncretic dative and accusative marker second person plural marker os. Secondly, the latter has given rise to a split into dative and accusative in the second person plural, producing an identical copy of the third person plural paradigm and an increase in syncretism.

The comparison of the third person object clitic paradigm with the strong pronoun and definite determiner paradigms shows that – very different from the dative clitic – the accusative clitic is strikingly similar to the definite articles.35

Importantly, the case of accusative lo combining both masculine and neuter gender is of high relevance to the discussion of invariant lo as the most important unmarked form in the non-standardized data. It is a featureless form “that can act as a surrogate for the entire category” (Bresnan 2001a: 61; Greenberg 1966) producing interesting morphosyntactic variability which is not restricted to a particular geographic region or dependent on extra-linguistic factors alone. Moreover, this invariant form covers more than one use. Lo is a syncretic form for the neuter, expressing third person only, and for the singular masculine, expressing third person, number and gender. In gender concord, the masculine subsumes the feminine. As shown in chapter one, section three, it is part of a complex aspect of Spanish syntax, namely the variability of the Spanish third person pronominal paradigm as a referential system, leísmo, loísmo and laísmo (Fernández Ordóñez 1999). Leísmo personal (personal leísmo) is the use of the dative le for the accusative lo referring to mainly singular male humans in Peninsular Spanish since the sixteenth century. Loísmo is the use of lo for le, and represents an extension of the accusative into the dative.

In traditional grammar, the variability is based on a twofold distinction, either animate (personal) vs. inanimate (things), or on eliminating gender in favour of case distinctions. Leísmo is a highly complex multisystem, showing distinctions based on geographical variability, contact with non-gender marking languages such as Quechua, Basque and some Amazonian languages, different usage in written and oral language, and finally the actual use compared to the educated “standard” use. In fact, co-variation of lo and le has been reported for Basque contact Spanish (Fernández Ordóñez 1994; Suñer 1989), Quechua bilingual Spanish (Mayer and Sánchez 2016) and for L2 English speakers with Hispanic Background in the United States (Luján and Parodi 1996).

2.4Specific lo (la) environments

Ormazabal and Romero (2004, 2007, 2010)36 have presented significant evidence, which justifies the following, now widely accepted categorization:

–First and second person accusative clitics can be grouped together with all dative clitics as agreement markers, to form one single agreement system.

–The third person clitic lo can be considered “a genuine case of determiner cliticization” (Ormazabal and Romero 2007: 341).37

This twofold categorization is warranted by the following differences:

- Third person direct object clitics show a much richer morphology (gender and number), with the accusative clitic lo the only clitic to preserve the neuter case features from Latin.38 This is a property they share with strong pronouns and determiners, as shown in Table 2.7.

- Third person clitics originated from demonstratives, while first and second person clitics do not and only the direct object clitic paradigm still exhibits the ‘pointing effect’ of demonstratives (Bhatt 2004). Indirect object clitics show a much more advanced grammaticalization stage and have become agreement morphemes.

- The single agreement system indiscriminately marks indirect and direct objects. Determiner clitics are direct object markers and have special syntactic functions exclusively available to the direct object clitic paradigm.

This categorical distinction not only allows for the default pronoun status of the accusative clitic lo as described below, but also triggers serious consequences for direct object clitic doubling with agreeing and non-agreeing clitics.

The default pronoun lo (and some instances of la) participates in at least two syntactic environments where the dative clitic le can never be found. These are (i) topic-anaphoric pronoun referring to topical propositional content; and (ii) determiner function in cleft constructions and nominalizations. The examples of these special functions, treated below, are by no means exhaustive39 but address the main and most relevant points that allow linking the ‘neuter’ accusative clitic to the information structural function of secondary topic;40 and to shed some light on differences between dialects. In the glosses, I use N for neuter in all instances of neuter lo.

2.4.1Lo as propositional anaphoric topic marker

In the double object construction in (28), the neuter clitic lo is an argument clitic in the grammatical role as direct object argument and refers to a propositional antecedent, to a specific event, or a clause.41 The clitic must appear left adjoined to the verbal host.

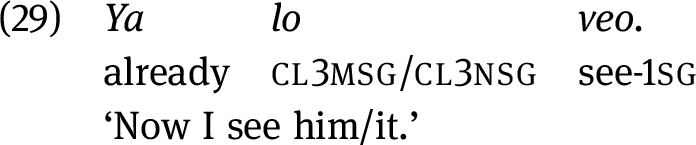

In (29) the argument clitic lo out of context may be open to ambiguous interpretation, as lo here can refer to an animate entity, e.g. a specific person or an inanimate entity, a specific thing.42 This is a perfect example of the double role of lo, linking it to the default clitic.

In both cases the event and the ‘thing’ must be part of common world knowledge of both participants in the communication or be anaphorically recoverable from the immediate discourse context.

The two functions of the direct object clitic lo as topic-anaphoric referring to propositional content and as referring to an animate/inanimate entity, are not available to the dative clitic le in standard Spanish varieties in which le is restricted to referential anaphoricity and indirect object agreement.

2.4.2Determiner cliticization

In certain determiner cliticization constructions the clitic lo lacks agreement and the pragmatic feature referentiality but retains the semantic feature definiteness. Here the clitic is phonologically dependent not on the verb but on another word, it always must appear left adjoined to any syntactic category. An example of this is lo in its function as as determiner in cleft constructions, where anaphoric lo que, lo cual, lo de refers to a sentential complement.

Example (30) shows neuter lo firstly in a lo que cleft construction followed by lo as a determiner in a coordinated noun phrase.

The pointing effect of the direct object clitic is well documented in crosslinguistic studies of pronouns. In these types of constructions lo que shows similarities to indefinite pronouns. Bhat (2004) points out the general need to distinguish between indefinite pronouns and ordinary noun phrases on two grounds: (i) on a semantic level, the location of speaker versus hearer has to be taken into account, and (ii) because indefinite pronouns belong to the pragmatic dimension. As he notes (2004: 3) “demonstratives denote objects that are not actually named, but pointed out”. This applies specifically to direct object clitics as determiners in nominalizations.

Neuter lo can also be used for generic expressions of the kind lo bueno, lo malo, lo feo (the good, the bad, the ugly), and is not replaceable by any other determiner. It can function as determiner with a variety of nominal categories (adjectives, adverbs, participles). For example, the noun phrase determiner lo with a nominalized adjective in (31) takes on the role of subject and demonstrates the lack of agreement and the retained semantic feature definiteness.

Co-occurrence of a clitic with a preposition as in (32),where lo/la are nominalised, is restricted to the direct object clitics lo(s) and also la(s) in determiner function. Unlike cleft constructions and determiners as nominalized clitics they maintain their gender specification and ensure referential identification of the represented entity.

These kinds of constructions demonstrate clearly the genetic background of third person clitics as a demonstrative in pointing to the event as cataphoric reference. Lo as a propositional (sentential) anaphor remains restricted to a verbal host, which makes it quite different from determiner clitics, which can select from several nominal and syntactic categories as their phonological host. Clitic placement left adjoined to their phonological host remains unchanged in all cases.

This brief exposition of the additional functions of direct object clitics has demonstrated that the third person object clitic paradigm is not a uniform class. Unlike indirect object clitics, the direct object clitic forms lo, la can be used as determiners that project certain kinds of phrases, as well as non-projecting words, as I will argue in the next section.

2.4.3An attempt at accommodating determiner clitics

The last two subsections have shown the unusual and multifunctional status of the direct object clitics, among others as the default direct object pronoun.43 To capture this important distinction I use the idea of a projection / dependence matrix (Toivonen 2003) to show the full distribution of Spanish pronouns and clitics in Table 2.9.

Table 2.9: Modified projection/dependence matrix

| non-projecting | projecting | |

| phonologically dependent | IO, DO clitics | DO determiners |

| not phonologically dependent | strong pronouns |

My representation of Spanish pronouns and third person clitics on the matrix shows that strong pronouns are full stress-bearing words, phonologically independent of any host, and able to project full phrases. The clitic paradigm is split into ‘true clitics’, indirect object, and direct object agreement markers, which are phonologically dependent on a verbal host and lack projecting capacity. The direct object clitics lo and la in determiner cliticization constructions, as documented in section 4.2, have some projecting capacity and are phonologically dependent on a range of nominal and syntactic categories.44

The typological classification of pronouns into PRO > WEAK > CLITIC (Cardinaletti and Starke 1996, 1999) does not allow this important distinction to be captured,45 whereas Toivonen’s new typology does. Hence, it allows the fine distinction between first and second person indirect and direct object clitics and third person indirect object clitics on the one hand, and the third person direct object clitics including the ‘unmarked’ exponent, neuter lo on the other to be brought out. This proposal accommodates the linking of grammaticized clitics and their interaction with semantic and pragmatic strategies of object marking in variation Spanish. Further, it is very useful for the distinction of anaphoric and grammatical agreement, which will be treated in chapter three.

In this section I have discussed the complex morphological classification of Spanish clitics and exposed their mixed properties. The genesis of the clitic paradigm in demonstratives, and their classification as deictic elements, has important consequences for clitic cluster constraints. The analysis of third person clitics as deictic elements seems natural and would offer a plausible explanation for the Person-Case Constraint as Spanish, like many other languages, disallows co-occurrence of two deictic elements. This issue will be further discussed in the next section, dealing with clitic cluster constraints.

2.5Clitic placement and alignment constraints

The previous section has established that clitics can occur either alone or in a clitic cluster and, when occurring in a cluster (33), they are subject to specific alignment constraints.

In this section I first present the basic surface structure constraints applied specifically to Spanish, before moving on to the Person-Case Constraint (Bonet 1991, 1995) for further restrictions on clitic clusters. The final subsection discusses various features of these constraints in an Optimality Theoretic approach in terms of more general markedness principles.

2.5.1Surface constraints

Clitic cluster constraints have been widely noticed and described by traditional grammarians. For example Bello (1984: 278) notes “la segunda persona va siempre antes de la primera, y cualquiera de las dos antes de la tercera; pero la forma se (oblicua o refleja) precede a todas” (The second person always precedes the first, and any one of the two has to appear before the third. But the form se (oblique and reflexive) precedes all).46

The most interesting case of first position se is third person clusters of dative le(s) with accusative lo(s), le la(s), where the dative le(s) changes to se as in se lo(s), se la(s).47 This co-occurrence constraint has been widely discussed, originally by Perlmutter (1971) who presented an analysis based on surface constraints in form of a template (35), mainly for Spanish but aiming at some universality.

Building on Perlmutter’s work, extra constraints have been proposed in the form of the me lui constraint focusing on high clitic order variation in a subset of closely related Catalan dialects (Bonet 1991, 1995), followed by Person-Case Constraint focusing mainly on morphology (Harris 1994, 1995; Pescarini 2005). The (Generalised) Person-Case Constraint moved on to discuss the syntax-morphology interface (Adger and Harbour 2007; Albizu 1997; Nevins 2007; Ormazabal and Romero 1998, 2002, 2007) still leaving a number of issues unexplained.

The earliest Transformational Grammar accounts (Dinnsen 1972; Perlmutter 1971) state that clitic ordering in Spanish is governed by two rules:

| (34) | Reflexive | > | Benefactive > Dative > Accusative Thematic case hierarchy48 (Dinnsen 1972: 181) |

| (35) | se II I III | The spurious se rule (Perlmutter 1971: 76) |

Focusing on Spanish and French, Perlmutter introduced surface structure constraints and filters assuming that clitics require to be generated in the same position in deep structure as the ordinary noun phrase. They then move into their respective clitic position obeying the surface structure constraints and filters in (35). The ‘spurious se rule’ in (35) shows the relative order of clitics applicable at least to Spanish and French (the Roman numerals represent second, first, and third person, respectively).

In Spanish, there are two surface positions for clitics; in finite clauses, they occupy the immediate preverbal position, and in non-finite clauses (with infinitives, gerunds and affirmative commands) they adjoin to the verb, verb finally; they are always contiguous.49 The clitic position is not available to noun phrases and nothing but another clitic in a clitic cluster can come between a clitic and the verb. The version in (36) shows the surface order of proclitics and enclitics in Spanish.

There is only one third person position, and the dative must precede the accusative. A common solution for this is to have the dative in the se slot. Grimshaw (1982a) argues that this is an unsupported reflexive that fails to parse dative and parses third person instead. Co-occurrence of two third person clitics places the accusative into the third person slot and transforms the dative into so called spurious se (see the spurious se rule in the next section). However, in this position we find two other instances of se, either a third person reflexive pronoun or a so-called ‘impersonal se’ which can only occur with a human subject.50 The extended version is useful for illustration purposes but the extra position is superfluous, as the application of the spurious se rule in (35) discards ungrammatical combinations.

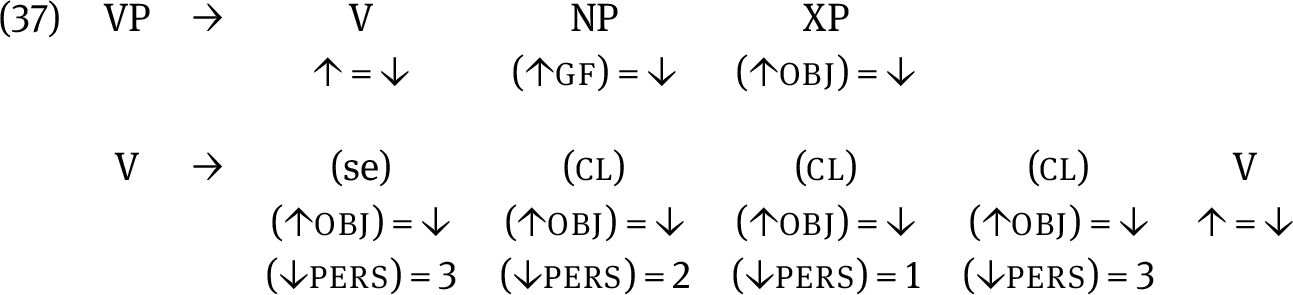

A surface structure constraint such as (35) is a surprising and unwelcome addition to the Transformational Grammar framework, but fits much better into Lexical-Functional Grammar, where it can be integrated into the Phrase Structure rules as first developed by Grimshaw (1982a) for French.

The extended verb phrase rule (VP) in (37) demonstrates preverbal clitic placement rules for Spanish and describes the surface structure of clitic clusters. The basic phrase-structure rules with their functional annotations generate correct c-structures and well-formed functional structures in dialects with agreeing clitics co-occurring with a co-indexed argument. This approach, originally due to Grimshaw (1982a: 90) for French clitics, is modified here for Spanish to incorporate Latin American leísmo clusters. The notation ↑ (up arrow) refers to the immediately dominating node, the ↓ (down arrow) to the node itself. The notation ↑=↓ (up equals down) means that the node’s information maps onto the same functional structure as the information added by the mother node.51

Second and first person show options of binding either one of the two internal arguments, the direct object (OBJ) or the indirect object (IOBJ), or, the external subject (SUBJ). The immediate and last preverbal position is taken by the third person and only binds either one of the two internal arguments. The first position is taken by spurious se, which as a reflexive clitic binds two arguments, the external subject, and either one of the two internal objects on argument structure, both expressing the same grammatical function.

In addition to these verb phrase rules we still need the ordering restrictions that Perlmutter’s template requires, which however can be regarded as constraints on how the options from rule (37) must be chosen.

Italian, Romanian, Greek, and Spanish share the ordering rule that indirect object clitics precede direct object clitics when forming clitic clusters. These rules apply straightforwardly to first and second person, however due to syncretism, grammatical relations are unmarked in their surface structure. On the other hand, third person clitics show overt marking of grammatical relations (indirect and direct object), and consequently a cluster of two third person clitics represents a mismatch between their morphological form and syntactic function.52

Here, an important constraint intervenes, which is based on a crosslinguistically attested dispreference for adjacency of the same morpheme. As it is a markedness constraint, it can be violated and dealt with on a language-specific basis (Grimshaw 1997a). Recall that in Spanish, except for tensed auxiliaries (lo había dicho- (s)he had said it) and other clitics, no other word can separate the clitic from the verb.53 Clitic clusters are inseparable and can combine up to three, with one of them an ethical dative.54 Similar constraints have been observed for Warlpiri by Hale (1973) and Simpson (1991). Conditions in Slavic languages are similar but clusters can exist of more than two elements at a time. This is also the case for Spanish and Romanian.

In the next subsection, I will discuss more recent approaches to alignment and cluster constraints most relevant to Romance and more specifically to Spanish.

2.5.2The Person-Case Constraint

Relevant to Spanish and the present discussion are constraints that disallow the co-occurrence of an accusative and a dative clitic if both are third person clitics. This has already been demonstrated in the extended verb phrase rule in (37). In the literature, the constraint is known as the Person-Case Constraint stating: “In a ditransitive, where both internal arguments are realized as phonologically weak elements, the direct object must be third person” (Adger and Harbour 2007: 2). In Spanish, to comply with the surface structure constraints (35) and (37) and to ensure that person agreement on the verb is unambiguous, the dative clitic le is substituted by spurious se when co-occurring with an accusative third person clitic as demonstrated in (38). This gives rise to the only opaque clitic se from a process of delinking and inserting morphosyntactic features.55

| (38) | Spurious se rule: |

| *le(s)DAT loACC → se lo |

Fernández Soriano (1999) argues that this constraint does not apply to noun phrase objects occurring in canonical position (39) that is in unmarked accusative/direct object – dative/indirect object word order.56

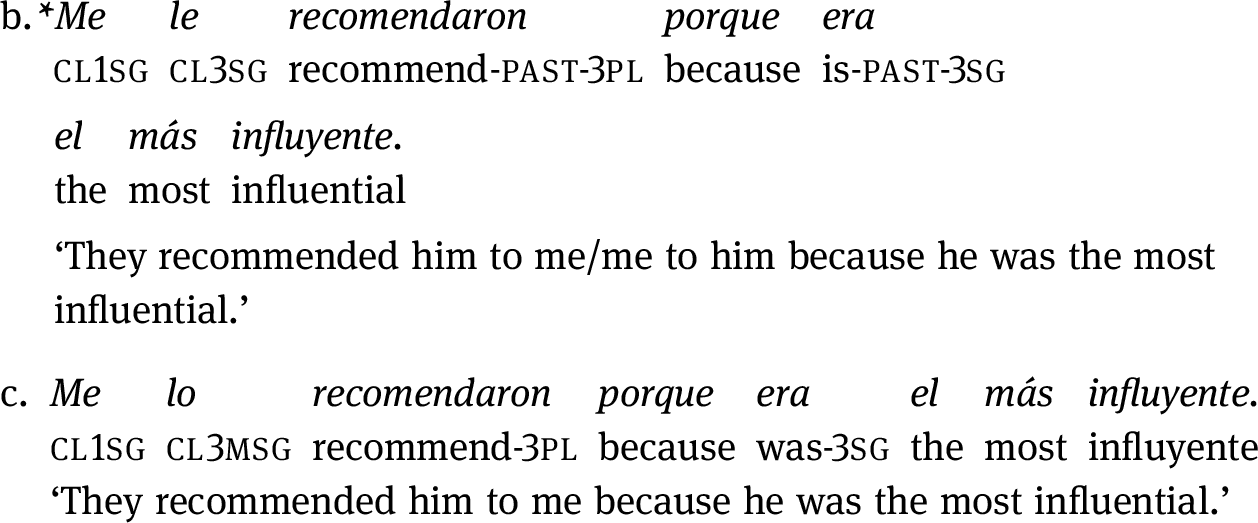

The rule does apply to clitic cluster and receives language and dialectal variety specific treatment. As shown in (40a), Peninsular Spanish requires either a strong pronoun in the indirect object position, or adding the full object (40b) to establish the grammatical role of the argument clitics.57

The Leísta Spanish variant in (41) referring to two animate objects does not violate the rule, as le does not mark the dative and allows to establish grammatical functions.

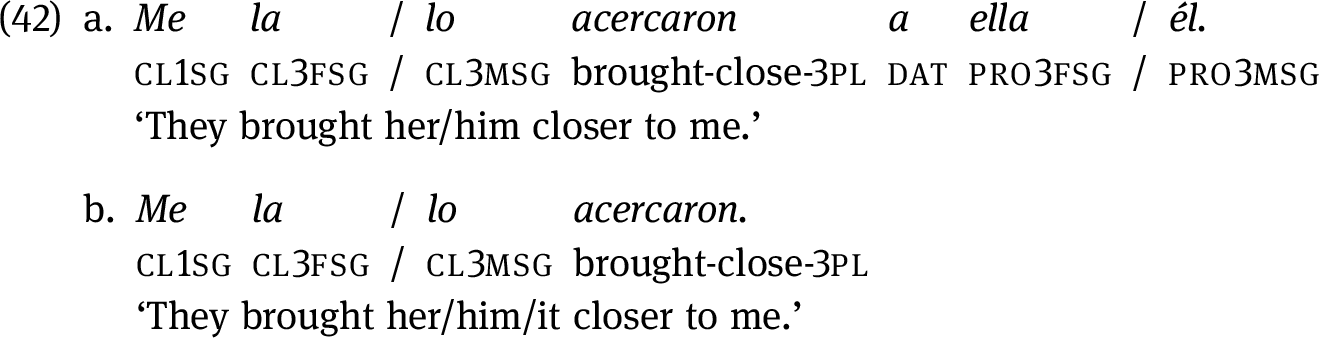

Rather than syntactic casemarking, (40a) is a case of idiosyncratic prepositional marking (Dalrymple 2001: 27), which should instead be glossed as semantic case GoalLOC marking an oblique. Examples (42) on the other hand show core argument marking with gender-specific clitics.

In sum, Peninsular Spanish seems to express a narrower range of grammatical relations by disallowing me le clusters. A possible reason could be the fact that leísmo is mainly restricted to male humans. Note that the gender-expressing anaphors in (42b) do not only refer to animate objects but also to inanimates, as for example, ella could refer to la piedra (the rock) and lo to el coche (the car). This question leads to Ormazabal and Romero’s Object Agreement Constraint.

The Object Agreement Constraint (43) is based on the Person-Case Constraint and an extensive analysis of leísmo, laísmo and loísmo.58 It is more comprehensive than the Person-Case Constraint and subsumes it (Ormazabal and Romero 2007: 336):

| (43) | If the verbal complex encodes object agreement, no other argument can be licensed through verbal agreement. |

In this minimalist account, the Bonet (1995) proposal is extended to include animacy as the important crosslinguistic factor in object marking, backed up by a widely attested restriction of multiple object marking. The constraint is only active when dative and accusative clitics as agreement markers overtly cross-reference the syntactically active objects on the verbal morphology. This aspect is important for the analysis of liberal clitic doubling with non-agreeing clitics; it will be further discussed in chapter five in terms of floating agreement.

In a different approach, Nevins (2007) focuses exclusively on person and the binary features [±Participant] and [±Author] for referring expressions. Nevins argues that the me lui effect and spurious se represent a depersonification of the third person, where in the cluster sequence se lo, spurious se “must have a featural representation of person beyond ‘nothing’” (283), hence the third person bears the features [–Author, –Participant] (Nevins 2007: 311). For morphological markedness, the ‘deletion’ of person ensures that person agreement on the verb is unambiguous. This proposal solves the Person Constraint for standard varieties, but as it leaves out the case/gender discussion it is not applicable to dialectal variation with non-agreeing clitics.

The proposal by Adger and Harbour (2007) is more applicable to the Latin American Spanish variability. They argue for a strong relationship between the Person-Case Constraint and case syncretism. This is indeed the case for Spanish, as shown in the discussion above (section three) of the Spanish clitic paradigm, the Person-Case Constraint applies only to the third person clitics. It has been found that the syncretic first and second person clitics are phonologically weak and do not distinguish overtly between direct and indirect object, whereas third person clitics do. Case syncretism involves the same marker for two core arguments, the dative and the accusative, where the latter is marked in accordance with a culture-sensitive animacy scale subject to diachronic change. For other languages, such as Greek, where the Person-Case Constraint does not fully correlate with case syncretism, the authors assume only partial case syncretism.

The accounts discussed so far do not provide an explicit answer, as they do not consider markedness constraints which reflect crosslinguistic variability based on pragmatic strategies.

2.5.3Markedness constraints

The remaining discussion of alignment takes markedness constraints into account. The theoretical basis is an Optimality Theory treatment, where morphology interacts with phonology based on a mechanism of violable constraint rankings (Grimshaw 1982a, 1997a, 1997b, 2001).59 The main tenet of Optimality Theory is that constraints are universal but the ranking of constraint hierarchies – hierarchy of expressions of features – is language specific and fixed in any given language. Different rankings of the same constraints predict the possible combinations.

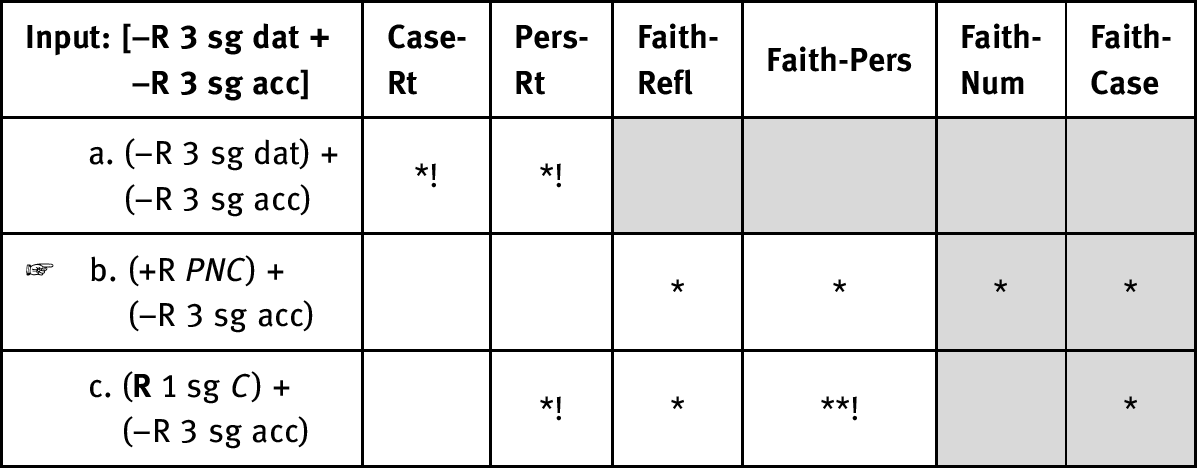

Grimshaw (2001) analyzes spurious se in Spanish by ranking a series of violable morphosyntactic restrictions and alignment constraints, as shown in Table 2.10, reproduced from Grimshaw (2001: 221, Tableau T8.16).

Table 2.10: Spurious se in the cluster se lo(s)/la(s)

For the cluster third person dative le and third person accusative lo(s)/la(s), the dative le, which is a clitic that parses person, number and case, surfaces as spurious se, a clitic devoid of person or case features, followed by an accusative clitic. This clitic parsing person, number and case locates itself at the rightmost edge. Candidate (b) thus satisfies all faithfulness constraints and alignment restrictions. Candidate (a), representing the combination le + lo/la, fulfils all faithfulness constraints but violates both positional restrictions PersRt and CaseRt. In candidate (c), the input for the first clitic shows person one instead of person three, and therefore violates fatally the person faithfulness constraint as well as the alignment PersRt constraint while being faithful to reflexivity and case. The letters in italics (PNC and C) state that the clitic has no specification for that property.

Table 2.10 clarifies that alignment constraints rank over all faithfulness constraints, which seem to follow an approximate order of FaithRt and FaithPers ≫ FaithNum. The ranking of FaithRt with respect to FaithPers, and of the positional constraints PersRt and CaseRt, are not clear at present. However, alignment of these positional constraints is understood and shows the pattern given in (44) (Grimshaw 2001: 222), where firstly a casemarked clitic needs to appear at the right edge, and secondly, the next clitic then marked for person needs to get pushed as far right as possible. The relative ranking between both constraints is difficult if not impossible to determine, since Spanish does not have a clitic showing the case feature but not the person feature. Since clitics specifying for case constitute a subset of a set specifying for person, and both align at the right edge, this does not pose a problem in the present theory.

However, combining two third person clitics equally specifying for person and case leads to violation of both constraints in (44) with both clitics competing for the same position. In a universal markedness hierarchy (Aissen 2003, among others), the dative outranks the accusative and yields thus the combination se lo by ruling out se le. This, however, changes under extensive leísmo as we shall see in chapter five on cluster variation in Latin American Spanish.

In sum, impossible combinations in Spanish will arise from “marked values for case, person, and/or reflexivity” (Grimshaw 2001: 226). However due to syncretic forms of first and second person, which do not show case overtly, ambiguities arise, as in (45a), where a strong pronoun occupies the canonical direct object position.60 The examples61 in (45) are from Grimshaw (2001), who argues that the template in (35) cannot account for these combinations.

The combination in (45b) is prohibited per Grimshaw but (45c) is allowable. However, the cluster in (45b) is perfectly possible in Latin American Leísta Spanish and is as ambiguous as (45a), which leads me to suspect that pragmatic factors might interact with alignment constraints.62 Under extensive leísmo the indirect object clitic replaces the direct object clitic and gender loss makes it difficult to identify the referent, giving rise to ambiguous structures. Therefore, and despite the difficulties mentioned, I argue that Perlmutter’s template in (35) and the extension in (37) do account for the leísmo example in (45b).

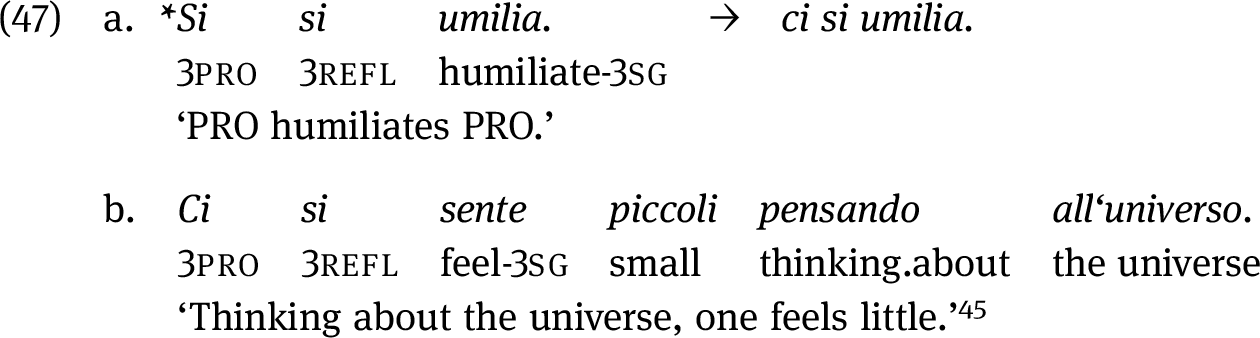

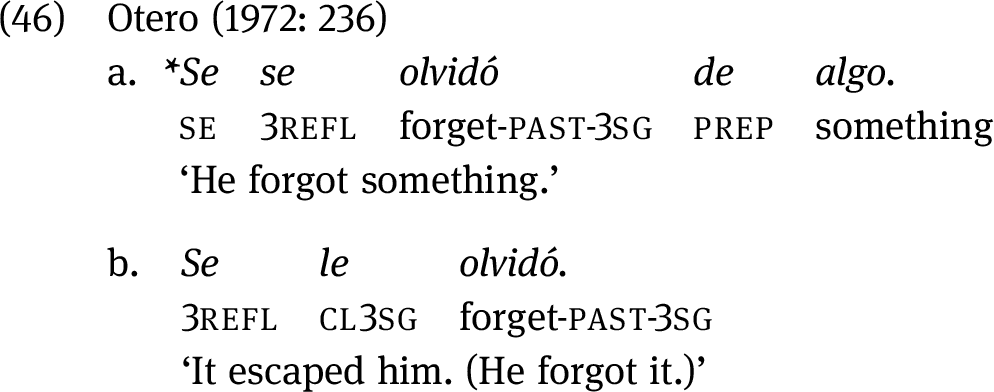

The next problem we encounter concerns spurious se when specifying AccRt instead of the general CaseRt, which implicitly refers to DativeRT as the dominant constraint (Grimshaw 2001: 237, ftn 5). Co-occurrence of spurious se (which is, following Perlmutter, PRO) and reflexive se is not possible, as in the example from Otero (1972) in (46a). Introducing the dative clitic in the anticausative reflexive construction in (46b) yields a non-argumental dative, not subject to the Person-Case Constraint.

Italian on the other hand, as shown by Otero (1972), circumvents this by using a suppletive form ci, which is homophonous with the first person plural clitic and the locative clitic, allows clusters as in (47b), with reflexive si and spurious ci63 which is analyzed as a pronoun.

The previous discussions have clarified the difference between the indirect object clitic le and the direct object clitics lo and la. Whereas the indirect object clitic can lead to ambiguous constructions, particularly under leísmo in Latin American Spanish, the direct object clitics facilitate identification of the object referent they agree with. I have shown in the modified verb phrase rules for Spanish in (37) that object agreement cross-referenced on the verb is restricted to a single object, and that spurious se binds one internal argument function (object) and the external argument function (subject) on argument structure as one argument.

The Spanish clitic system is much less complicated than the Barceloní as discussed by Bonet (1991, 1995), for example, as it only produces one opaque form in clitic clusters and does not exhibit the binary distinction of phonological vs syntactic clitics that some dialects of Catalan show. Hence, in languages exhibiting this distinction, it is possible to analyze clitic clusters taking language-specific markedness constraints into account.

Clitics in Limeño Spanish contact varieties, and specifically the direct object clitic paradigm, are affected by grammaticalization processes resulting in morphological simplification.

2.6Summary

In this chapter I have discussed the morphological classification of Spanish clitics, placement, surface constraints and co-occurrence in clitic clusters. The typological classification of Spanish clitics based on the tripartite division by Cardinaletti and Starke (1996) proved too inflexible to capture the mixed properties of third person direct object clitics. I have therefore used a new typology based on a projection and phonological dependence matrix (Toivonen 2003) to give a more precise categorization. This was achieved by separating first, second and third percon indirect and direct object clitics as agreement markers, on the one hand, from third person direct object clitics in determiner cliticization exhibiting some projecting capacity, on the other. This fine-grained distinction allows for the linking of grammaticized clitics and their interaction with semantic and pragmatic object marking strategies in variation Spanish to a distinction in grammatical and anaphoric agreement, similar to the proposal for Chicheŵa (Bresnan and Mchombo 1987), to be discussed in the next chapter. The distinction also helps to explain invariant lo and locative doubling, and link them to a specific information structure role, as we shall see.

Among the many constraints for clitics and clusters exposed above, the Object Agreement Constraint is the broadest, as it prevents two internal arguments from agreeing concurrently with the verb that is being marked. Languages with no overt verb-object agreement relations, like Turkish and Japanese, don’t have Object Agreement Constraints at all. Others show a clear distinction between first / second versus third person, among them Spanish and other Romance languages. This is the second important result and feeds directly into the discussion about objects and clitics in the next chapter.