Chapter 16: A Dictator Takes the Helm

The brazen bombing of the Winter Palace captured the full and undivided attention of the imperial government. The Tsar called in all of his cabinet ministers and close family members for conferences. On February 8, three days after the explosion, Tsar Alexander II held a large council of state. While the ministers remained largely silent, his 34-year old son and heir Alexander Alexandrovitch took the floor. After expressing strong opposition to any notion of a constitution, he proposed a very simple idea. Appoint a single supreme commander, as in a time of war! He would be an absolute dictator and that way, could be in a position to do battle with the enemies of the state. The vision of the “success” of the White Terror of the 1860s was invoked.414

These proposals were not Alexander Alexandrovitch’s own ideas. Over time, the younger Alexander had became a tool of the St. Petersburg reactionary faction entrenched in the Anichkov Palace, where the heir had his headquarters. One of the arch-conservatives, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, had been his head instructor. Pobedonostsev continued to be the heir’s mentor after he reached adulthood. Alexander Alexandrovitch grew into a large bear of a man, but he was not a mental giant, to put it charitably. He had not been groomed for the throne. That honor had gone to his older brother Nicholas, who then died unexpectedly in 1865. Alexander Alexandrovitch was a tippler, a habit whose extent he tried to conceal from his wife Maria Feodorovna, the former Princess Dagmar of Denmark. His big pleasures in life were fishing, hunting, and drinking. His idea of fun was to have his aide carry a concealed flask of cognac while on expeditions with Dagmar. When she took a moment’s leave, he would have the flask brought out in a flash for a quick swig, then concealed again by the aide before her return. Unlike his father, Alexander Alexandrovitch was not at all tempted by Western liberal thought. He was a staunch advocate of what we would today call “family values.” He was very moral and religious. He was outraged and bitterly offended by his father’s long running and scarcely concealed affair with Katia Dolgorukov.415

The reactionary party that mentored Alexander Alexandrovitch issued a sort of manifesto of counter-reform. In opposition to the idea of a constitution, the conservatives presented the model of a “living popular autocrat.” The tsar must remain an autocrat, and never devolve into a mere “chief executive.” They denounced the idea of a “bureaucracy contaminated by nihilism.”

When Alexander the son proposed appointing a single military commander to serve as absolute dictator, his father responded that he was not in agreement with the idea. He would think about it. But that night, Alexander the father hardly slept. The next day, at a reconvened council of state, Tsar Alexander II once again heard out the proposition of his son and his advisors for setting up a dictatorship. Alexander, to everyone’s surprise, now reversed course and announced that he was accepting the concept. But when they heard who he had in mind to fill the job, they were even more stupefied. Alexander announced that he was appointing Mikhail Loris- Melikov.416

This unexpected selection was actually a shrewd decision on the part of the Emperor. The naming of the 56-year old Loris-Melikov shocked the right wingers because he was by no means a conservative, and because he was a total St. Petersburg outsider. He was not even a Russian, he was an Armenian. Although he had noble antecedents, Loris-Melikov’s father had been a successful merchant. Loris-Melikov had had a fine military career, working his way into a position as a general, fighting against the Turks in the Balkans, and fighting against nasty rebels in what remains today a hotbed of terrorism, the mountainous area of Chechnya and Georgia. He had distinguished himself during the Russo-Turkish war, not only by besieging Turkish outposts until they surrendered, but also because while doing so, he persuaded the local populations to accept the billeting of Russian soldiers. He had actually managed to return part of his budget to the state treasury, a virtually unheard-of accomplishment. He had also proved to be an excellent civil administrator. He had helped fight off an outbreak of the plague in Astrakhan province, on the Caspian Sea. He had been perceived as a success fighting terrorists while serving as governor-general of Kharkov, his current position when Alexander called upon him to become the dictator. Loris-Melikov had proved capable of taking a hard line on terror while, at the same time, managing public opinion and avoiding mindless excesses of repression.417

A sense of anticipation mixed with apprehension hung over the date of February 19, 1880. Ceremonies were scheduled to commemorate both the 25th anniversary of Alexander’s coronation, and the 19th anniversary of his decree freeing the serfs. It was feared that the terrorists would strike again. However, the event went off without a hitch as the Emperor was cheered by large crowds.

But when Loris-Melikov returned to his home the next day shortly after 2 pm, as he dismounted from his carriage a young man came out of nowhere and ambushed him, firing a revolver. The shot penetrated Loris-Melikov’s overcoat and his uniform, but missed his body. With a reaction born of years of combat, Loris-Melikov hit the ground before the attacker could fire a second shot. Then, just as quickly, he sprang back up to his feet and pounced on the assailant, knocking him to the ground. By the time his stunned Cossack guards could reach the fight, Loris-Melikov had already disarmed the assassin.

Loris-Melikov’s personal courage and audacity fighting off the attack made him a hero with the public.418 None but the most sensitive seemed to be upset when a military tribunal convened at Loris-Melikov’s behest condemned the terrorist, one Hippolyte Mlodetski, to be publicly hanged the following day. Even Narodnaya Volya distanced itself from Mlodetski. Two days after the attack, when Mlodetski was already dead, the Executive Committee issued a communiqué which rather egotistically stated:

With reference to the attempt of February 20, the Executive Committee find it necessary to state that its inception and execution were due solely to private initiative. It is a fact that Mlodetski offered his services to the committee for some terrorist act. But he was unwilling to await a decision and he proceeded to carry through his attempt without knowledge and without the assistance of the Executive Committee.419

Loris-Melikov as dictator rapidly showed himself to be every bit the capable administrator and reformer he had promised to be, given his earlier career filled with successes. He took the initiative to force the reactionary Dmitri Tolstoy into involuntary retirement as minister of education. He abolished the Third Section, reassigning its security functions to the ministry of the interior. Loris-Melikov flirted with Russian students, granting them long suppressed demands such as the right to organize their own independent study groups and to create mutual aid societies to help poorer students. He eased censorship restrictions on the press.420 He avoided overreacting to a published humor piece that placed him on the same dance floor with such figures as Vera Zasulitch, Lev Hartmann (Perovskaya’s fictitious husband from Moscow, whom Russia was then trying unsuccessfully to extradite from France), and Nikolai Chernyshevsky. The conservatives were appalled.421 By August 1880, Loris-Melikov was able to announce that his measures had been a success, and that there was no more need for him to hold plenary emergency powers as head of a Supreme Administrative Commission. In short, his dictatorship was at an end. He would become minister of the interior and chief of police.422

Under Loris-Melikov the Russian government made meaningful strides in confronting the terrorist threat. Following his capture in November of 1879, the authorities in Odessa had used bullying, torture and strong arm tactics to try to get Grigory Goldenberg to talk. None of it worked. They were facing a determined radical.

Then the interrogation of Goldenberg was taken over by a young Odessa assistant prosecutor named Alexander Dobrzhinsky. Dobrzhinsky intuitively understood something many others in the Russian law enforcement structure (similar to those in the United States and elsewhere today) had failed to grasp. Rather than trying to torture, intimidate, or overpower the prisoner, Dobrzhinsky applied a fundamental insight into the persona of the terrorist. The best and, perhaps the only, way to obtain meaningful communications from a terrorist is to suspend the normal framework of reality. One must enter into the delusional alternative universe of the terrorist. Dobrzhinsky did just that. Not only did he treat the person being interviewed with sympathy, he actually accepted without reservation, at least for purposes of the interview, the viewpoint of the interviewee. An account by Olga Lyubatovich of her 1882 interview by Dobrzhinsky reveals how skillful and perceptive he was as an investigator speaking with terrorists. He accepted their world view for the purpose of finding out much more about its details. One of his favorite techniques was to propose that the terrorist write a letter to the Tsar, expounding on and trying to convince the Emperor of his or her point of view.

As part of his insight, Dobrzhinsky also understood that the terrorist has an enlarged ego. The terrorist thirsts after legacy and glory. He thus becomes easily deluded into uncritical belief in his own plans of action. Dobrzhinsky exploited these characteristics in Goldenberg.

A “Southern” radical turned informant named Feodor “Fedka” Kuritsyn was placed with Goldenberg as a cell mate. He had already been incarcerated for three years. Fedka had been a talented, cheerful youth, an amateur musician and singer, and had studied at the Kharkov Veterinary Institute. But by now he was a cowed and broken man. His eyes were sunken, his voice trembled. He told Goldenberg he was going out of his mind. He begged Goldenberg to relieve him of his loneliness.

Slowly, Goldenberg began to talk to Fedka. Fedka was getting ready to be put on trial. Fedka’s only joy was whispering, so that nothing could be overheard, to Goldenberg. Fedka praised him for not giving in to the swine. When he learned that Goldenberg had executed Kropotkin, the “butcher of the Kharkov students,” Fedka’s admiration knew no bounds. He kept repeating how happy he was to be in the same cell as such a heroic person after three years of isolation. “You are doing such splendid things!” He spoke of how much it mattered to him and helped him, and added to his strength. So, Goldenberg kept on bragging about his exploits and those of the terrorists. He told him all about the Moscow tunnel, and about the planting of the mine in Alexandrovsk. Fedka and three of his fellow Odessa rebels were tried. Kuritsyn’s co-defendants were sent to the scaffold and, on December 7, they were all hanged. Kuritsyn’s sentence was commuted to penal servitude. In view of his three years in prison, Kuritsyn was given exile.

Goldenberg’s tortures were abandoned. He seemed to have been forgotten by the jailers. He spent his time “preparing” Fedka for his exile. Kuritsyn would be going to Kharkov and from there to Siberia. Goldenberg bragged to Fedka that he knew of safe havens where Fedka could go in Kharkov. He generously shared his knowledge about the contacts and safe houses there. Among his statements to Fedka: “And the very warmest greetings to Sonia Perovskaya, if she has returned from Moscow to Kharkov.” At the beginning of January, Fedka left prison. His goodbye to Goldenberg was a sad parting, with Fedka nearly breaking down in tears.423

Two days later, on January 15, Goldenberg was summoned for his new official interrogation. Everything was different now. Dobrzhinsky behaved extremely politely, almost benevolently, toward Goldenberg. He asked very few questions, and he did most of the talking himself. From what he said it appeared that the investigators knew absolutely everything. Goldenberg’s comrades, captured recently in various places, were confessing and giving frank evidence. Many were honestly repenting, many were writing long and very substantial explanations, giving names, dates and addresses. They were young and still hoped by means of honest confession to start afresh. A huge, nationwide process of disintegration of the revolutionary party was taking place. Goldenberg asked who these young people were. Names did not matter, Dobrzhinsky replied.

Dobrzhinsky went on talking, about the Lipetsk congress, reeling off names and aliases. He described the meetings in St. Petersburg taverns that went on before Solovyev’s attempt. He talked about the Moscow tunnel, and the plans to mine Malaya Sadovaya street in St. Petersburg. This upset Goldenberg badly. It was a top secret plan, which the “Janitor” had only mentioned in passing. Could the jailer have overheard him whispering about this to Fedka? This caused something to snap in Goldenberg, as if he had lost his base of support. Eventually, in the face of more confrontation with details, Goldenberg came to a cold and depressing realization. He himself was the source of the information. He had given it away through Fedka.

Dobrzhinsky played to Goldenberg’s ego. He praised the extremists of the Sixties as being the true “best people we have” and “the flower of the nation.” They were perishing for no good reason. “Russia must be saved!” he declared. He portrayed the fate of the nation as a tremendous drama, in which Goldenberg could take the lead role. “We must stop this orgy of executions, deaths, spite and mutual distrust. You think everything at the top is calm and unanimous? I know some very highly placed persons who rage when they hear of new arrests and court martials. What an unfortunate country this is!” He pointed out that the Bulgarians, the Romanians and the Finns all had constitutional or representative government in some form, because the Russians had granted it to them. And yet, the Russians did not.

“There is no one who could do more than you, Mr. Goldenberg, to help Russia.” In the nights which followed, Goldenberg experienced delusions of grandeur. He appeared from heaven like the Messiah, like Jesus. In these visions he was appealing to the government and to the revolutionaries alike. He became convinced that it was his fate, his destiny, to save thousands of lives and stop the bloodshed. And in the wake of this vision, he began his confessions. Dobrzhinsky kept on with massaging Goldenberg’s ego. Goldenberg was asked to describe the revolutionaries he knew. And he knew a great deal. After giving a written deposition Dobrzhinsky personally brought him to St. Petersburg and had him meet with Loris-Melikov. Loris-Melikov talked the same line as Dobrzhinsky, calling Goldenberg a Moses, leading his people out of the desert to the promised land, to peace and repose. Goldenberg was thrilled. And Goldenberg kept talking. Eventually he would write “descriptions” of 143 people involved with the radical movement, including the leaders of Narodnaya Volya.

Tsar Alexander II read with great interest Loris-Melikov’s report on the interviews with Goldenberg. Goldenberg’s identification of Kviatkovsky was regarded as a particularly important turning point. He made a note, “I consider this a most important discovery.”424

On the night of May 21, 1880, the long suffering Empress Marie finally died. The Tsar allowed just 40 days of mourning to pass before he announced to his ministers his intention to marry Katia Dolgorukov. Alexander obstinately rebuffed every criticism of this intention. The marriage ceremony was performed, behind closed doors with only a few selected witnesses, on July 6, 1880. This formalized and legitimized an affair that had already been going on for 15 years, and that had already produced three children. The next day, when word of the secret marriage was announced, there was profound indignation in Alexander’s court. Nevertheless, Alexander signed a proclamation making Katia and her children royal highnesses. From that point forward, Katia frequently sat in on meetings between Alexander and Loris-Melikov. Loris-Melikov also engaged, on occasion, in private conferences with Katia. The Tsar was pleased that he did so.425 When Alexander Alexandrovitch returned to the capital and learned of his father’s remarriage, he was shocked.

Alexander, the father, was revitalized by insisting on bringing his relationship with Katia and the three children out into the open and by insisting, in the face of substantial behind-the-scenes intrigues against her, that Katia be accorded the dignity and respect due his spouse. With Katia and Loris-Melikov supporting him, Alexander at long last freed himself from the yoke of domination by conservative advisors. Katia and her three children immensely enjoyed their new status, being freed from the shadows. Katia now insisted on going everywhere with her new husband. She personally accompanied him on his annual trip to Livadia, in the Crimea, in August 1880. Alexander Alexandrovitch also traveled to Livadia along with his wife Dagmar and their children. There he was deeply disconcerted to find Katia and her children basking in the suites that had formerly belonged to Alexander Alexandrovitch’s mother. In a snit, he and his wife threatened to leave the Crimea for a vacation in Denmark (Dagmar’s native country). Alexander, the father, told Alexander, the son, he would cease to be the heir, if he acted that way. Alexander Alexandrovitch stayed on in the Crimea, but continued to be unhappy. Finally he got permission to return to St. Petersburg.

Loris-Melikov also accompanied Tsar Alexander II to the Crimea. He was tasked with working on Alexander’s newest reform project – a preliminary step in the direction of a potential constitution for Russia.426 Ever the diligent administrator, Loris-Melikov presented Alexander with a series of options. The centerpiece of the proposal, which Alexander ultimately endorsed, was the addition of certain delegates – members of a locally elected body, the zemstvo -to the Council of State, the group responsible for advising the Tsar on law and policy. It was not a parliament, but it was a step in the direction of a more republican form of government than anything imperial Russia had ever seen.427

Two commonly shared traits of terrorists are their loose overall grip on reality, and their political beliefs which are typically imbued with fantasy and a total lack of any practicality. These traits were amply demonstrated by Perovskaya in the aftermath of the Winter Palace bombing. Tsar Alexander II’s public and pronounced shift to the left, with the guidance of Loris-Melikov, sapped Narodnaya Volya of much of the support for its terrorist tactics among the liberals of Russian society. Cash donations from “legals” dried up, straining the group’s finances.428 The notion that the assassination of Alexander would by itself trigger some spontaneous mass uprising that would vindicate the position of the terrorists was pure wishful thinking. Eliminating Alexander, in view of the reactionary element of the St. Petersburg power structure for whom the heir Alexander Alexandrovitch was in essence a puppet, was now an extremely foolish course of action from a political point of view. Alexander was already heading in policy directions Narodnaya Volya had publicly requested, liberalizing press restrictions and granting an increased role in lawmaking to elected local representatives in the face of opposition from conservatives. But Sonia steadfastly refused to allow her compatriots to relent in their efforts to assassinate Alexander.429

In late March of 1880, Sonia and the others on the Executive Committee learned, through Kletochnikov, of Goldenberg’s revelations. Soon afterwards, Sonia traveled under her false passport to Odessa. There, Vera Figner was in charge of Narodnaya Volya operations. Figner was busy plotting the assassination of S. F. Panyutin, chief of staff of Count Totleben, the governor-general. Perovskaya countermanded this project. Pointedly, she reminded Figner that the Executive Committee had resolved to devote all of its attention and resources to killing Alexander. Lesser officials were to be attacked only if it did not in any way prejudice the attack on the Tsar. Sonia redirected the Odessa effort to be a plan to assassinate the Tsar. The method would be to dig a tunnel under the street, in which a mine would explode while he was passing overhead in the process of transferring from the train station to the steamboat wharf. Perovskaya expected the Tsar to pass through Odessa to make this transfer in May. This tunneling scheme obviously had much in common with the earlier Moscow efforts coordinated by Sonia. Once again she posed as a wife, this time, the spouse of a shopkeeper. Figner raised the sum of 1,000 rubles to open a grocery shop on Italianskaya Street, where the Tsar was expected to pass. Narodnaya Volya members were assigned to work daily shifts digging a tunnel from the shop to the street.

Perovskaya wanted Grigory Isaev as part of her team. He had proven his superior merit as a tunneler during the Moscow attempt. Isaev arrived shortly after Perovskaya, together with Anna Yakimova. The tunneling, although very arduous, was successful in reaching the middle of Italianskaya Street, where the Tsar’s route would pass, but the terrorists encountered other problems. Isaev blew off three of his fingers in an experiment with the explosives. Then it was learned that the Tsar had changed his plans and was no longer intending to visit Odessa. The Odessa mine project was declared a failure and abandoned, with the hole refilled.430

Although Perovskaya was posing as Isaev’s fictitious shopkeeping spouse, in fact, Isaev and Anna Yakimova, code named “Baska,” became lovers. When Isaev suffered the explosion accident, Yakimova risked her life to take him to the hospital and to stay by his side during his emergency treatment. Being an outlaw living underground without a passport, for “Baska” every moment visiting in the hospital was precarious.

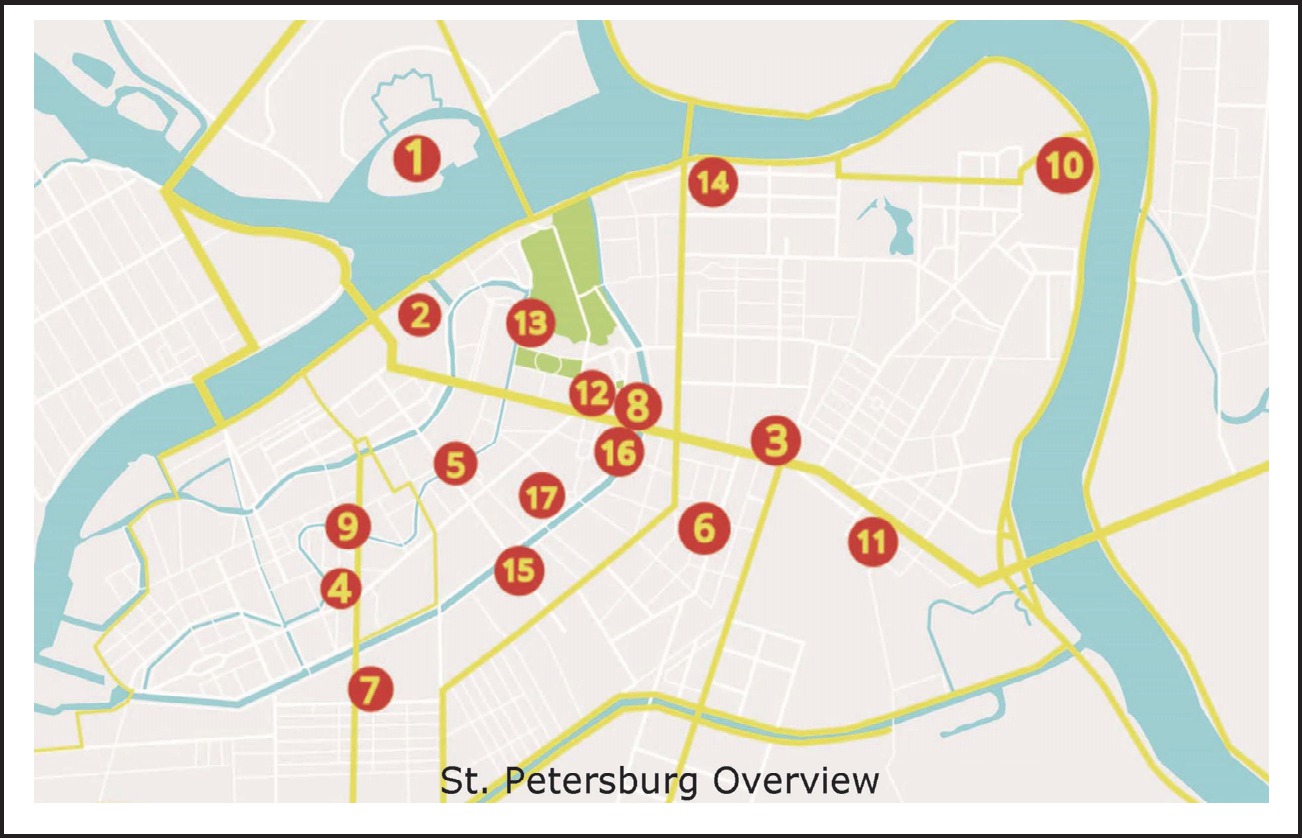

St. Petersburg Overview Map

Key to Locations:

(1) St. Peter and Paul Fortress

(2) Palace Square (in front of Winter Palace)

(3) Narodnaya Volya safehouse – Kibalchich residence

(4) Narodnaya Volya safehouse – Khalturin stayed here after WP explosion

(5) Kamenni Bridge

(6) Narodnaya Volya apartment – Kolodkevitch residence

(7) Rot Ismailovsky Polk – residence of Perovskaya and Zhelyabov

(8) Trigoni apartment – site of Zhelyabov arrest

(9) Voznesensky Ave. “headquarters” of the Narodnaya Volya

(10) Smolny Monastery grounds – where bombers practiced Feb. 28, 1881

(11) 5 Telezhnaya St. – residence of Helfman

(12) Cheese shop location in the Malaya Sadovaya

(13) Ekaterinsky Canal embankment, site of the assassination

(14) Preliminary House of Detention – Perovskaya’s last night spent here

(15) Semyonovsky Square – site of the execution

(16) Nevsky Prospect in front of Anichkov Palace – site of Perovskaya arrest

(17) Apraxin Dvor