1

“Ready to Turn the World Upside Down”

The “Gang of Four,” Feminist Pioneers in Chicago

This chapter highlights the story of four young Jewish feminists—Amy Kesselman, Heather Booth, Naomi Weisstein, and Vivian Rothstein—who were in the vanguard of the women’s liberation movement in Chicago as it took shape in the late 1960s. At the time of their involvement with the first glimmerings of women’s liberation, none of these pioneering radical feminists recognized themselves or acted as “Jewish” women seeking a revolution in sex and gender roles. Like the Jewish women who went south to participate in the civil rights struggle a few years earlier, they “just didn’t think of it then.”1 The powerful ideology of the new women’s movement drew them and colleagues of other faiths and backgrounds into a common endeavor that they hoped would radically change society.

The women chronicled their experience as radical feminists and their remarkable friendship in the article “Our Gang of Four: Female Friendship and Women’s Liberation,” published in The Feminist Memoir Project, a 1998 anthology.2 All four were part of the West Side Group, the nation’s first sustained women’s liberation group, which began in Chicago in 1967.3 Friendships such as those that developed among Heather Booth, Amy Kesselman, Vivian Rothstein, and Naomi Weisstein formed a pivotal part of second-wave feminism; they were “central to the energy and insights that emerged among women’s liberation activists in the 1960s,” the Gang of Four wrote.4 Female friendships empowered women and the movement, becoming the matrix for its revolutionary ideas.

“Our Gang of Four” focuses on the women’s family histories and their involvement in the social movements of the 1960s. The one feature that is not mentioned, except in the case of Rothstein, the daughter of Holocaust refugees, is the women’s Jewishness. Until I contacted Amy Kesselman, the four friends had never spoken about their Jewish backgrounds to each other—neither in the article nor in forty years of friendship. Perhaps this was because they perceived little commonality to their Jewish identities or because the issue had never arisen in their feminist work. Or perhaps the women sensed an antagonism between the particularities of ethnicity and religion and the dream of universality that guided the women’s movement. Because they were secular Jews or atheists, the meaning of Jewishness in their lives had been camouflaged by the cultural association of Jewishness with religion and, for some, with middle-class striving and privilege. In the views of some in the group, American Jews had seemed to turn away from a commitment to a social justice agenda. Also problematic was that Judaism did not offer women a central role. Like others in women’s liberation, the four friends focused their attention on class and race as they intersected with the problems of sexism. It was unclear how the constituent elements of American Jewish life fit into this framework.5

As a consequence, the bond of Jewishness among the women remained invisible, though implicit, in their friendship. Only when I came to the four with questions about Jewish identity and its relation to women’s liberation did they begin to explore Jewishness as a personal and political issue. We conducted two long telephone conversations, one about the women’s backgrounds and beliefs as Jews and feminists and the other about the Holocaust, and also shared correspondence on these topics. The stories that emerged point to the significance of Jewishness in these women’s lives, influences that were melded with value systems that developed from the women’s participation in the social networks of their cohort.

Although at the time of the women’s involvement in the movement, they did not acknowledge Jewish influences on their activism, the Gang of Four came from significant but different Jewish backgrounds: secular Yiddish / Communist Party radicalism; Orthodox-Conservative suburban; outsider refugee. Each had some Jewish education, whether formal (Yiddish shul, synagogue, and Hebrew school) or informal (Jewish community centers or Labor Zionist camp). Heather Booth framed it this way: “Many of the elements of Judaism were consciously part of my upbringing.” While several would have specified an antireligious Jewishness rather than Judaism, they might well have shared her appraisal.

For each of the four, ethnic/religious background came together with other elements of personal and collective identity that molded the early women’s liberation movement. “I couldn’t say where one [part of my identity began and one] ended,” Booth said. “Was I who I was because I was in a loving family, because we shared common values, because I was a woman, because I was white, because I was in Brooklyn? They were all part of a common definition.” Fluid and multiple, the varied aspects of identity intermingled, becoming more or less salient over time, depending on social context and the life course. For these women’s liberationists, Jewishness was one of the primary constituents of this mix.

The story of Marilyn Webb forms a coda to this chapter. In graduate school at the University of Chicago, Webb met the Gang of Four and other Chicago feminists and joined the movement to liberate women from the oppressive beliefs and structures of their lives. Moving to Washington, D.C., she was instrumental in starting D.C. Women’s Liberation, one of the most vital of early movement groups. With Shulamith Firestone, Webb participated in a foundational moment of radical feminism at the Nixon counter-inaugural rally in Washington in 1969. Like other Jewish women’s liberationists, she disregarded her Jewish identity during her movement years, only connecting to her roots decades later.

Amy Kesselman, Heather Booth, Vivian Rothstein, Naomi Weisstein: “Our Vision of Beloved Community”

In 1966, fifty women, including Heather Booth and Marilyn Webb of Chicago, attended a national conference of the radical organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), at the University of Chicago.6 For three days, the women discussed a memo written the previous year by Mary King and Casey Hayden about sexism in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The first to publicly air grievances against male superiority in the civil rights movement, the memo encouraged the women to think about their own experiences with SDS’s sexual politics, but they were not yet ready to break with the male-dominated New Left.7

The following year and through 1968, groups of young women’s liberationists spontaneously formed throughout the country, organizing to protest the sexism they confronted in everyday life, including on the New Left. Shulamith Firestone, a twenty-two-year-old former Orthodox Jew from St. Louis, was one of the Jewish women whose actions helped to stimulate the rise of women’s liberation in Chicago; other early centers of women’s liberation activism included Seattle, Detroit, Toronto, and Gainesville, Florida.8 Memos and workshops that grew out of SDS and the civil rights movement had been precursors to the formation of these groups.9

Firestone, a young artist studying at the Chicago Art Institute who was unknown to other Chicago activists, came into the spotlight during a weekend convention of the National Conference for New Politics (NCNP) held in Chicago on Labor Day 1967. About two thousand activists had gathered at the conference to debate the Vietnam War, black nationalism, and whether to run a third-party ticket headed by Martin Luther King, Jr., the convention’s keynote speaker, and one of the radical youths’ most admired figures, Dr. Benjamin Spock.10

Backroom conniving mixed with pandemonium on the ballroom floor at Palmer House, where the convention was held. A women’s caucus met for days, framing a minority report that called for free abortion and birth control; an overhaul of marriage, divorce, and property laws; and an end to sexual stereotyping in the media. But conference chairman William Pepper refused to accept the women’s report, calling it insignificant. He told them that in any event, he already had one from a women’s group, Women’s Strike for Peace, even though theirs addressed peace issues, not gender. Allowing a young man to address the NCNP about a Native American resolution, Pepper refused to permit women’s caucus representatives to speak. “Infuriated, we rushed the podium,” activist Jo Freeman recalled, “where the men only laughed at our outrage. When Shulie reached Pepper, he literally patted her on the head. ‘Cool down, little girl,’ he said. ‘We have more important things to do here than talk about women’s problems.’ Shulie didn’t cool down and neither did I. . . . The other women responded to our rage. We continued to meet almost weekly, for seven months. . . . We talked. And we wrote.”11

Following the incident, Firestone and Freeman organized the Chicago West Side Group, so named because it met at Freeman’s house on the west side of the city. In addition to Freeman and Firestone, members included Amy Kesselman, Fran Romanski, Laya Firestone (Shulamith’s sister), and Heather Booth and Naomi Weisstein, whose course on women at the Free University at the University of Chicago, first taught in 1966, served as a catalyst for Freeman.12 Vivian Rothstein, Sue Munaker, and Evelyn (Evi) Goldfield came six months later, with Linda Freeman and Sara Evans Boyte joining within the year. These dozen women were the regulars, although another dozen or so variously attended meetings.13 The West Side Group used the phrase “women’s liberation” in an early article and in its newsletter, the Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement, published from 1968 through 1969, helping to spread the goals of the movement around the country.14

“Ready to turn the world upside down,” in Naomi Weisstein’s words, the West Side women “talked incessantly”: “We talked about the contempt and hostility that we felt from the males on the New Left, and we talked about our inability to speak in public. Why had this happened? All of us had once been such feisty little suckers. But mostly we were exhilarated. We were ecstatic.”15 It was as if the NCNP “had broken a dam,” Sara Evans wrote in Personal Politics, one of the first histories of the movement. When the Chicago women heard the message—“sometimes in the form of the words ‘women’s liberation’—their first response, over and over again, was exhilaration and relief.”16

Jo Freeman gave Heather Booth credit for spinning off new women’s liberation groups in Chicago, where several new groups formed. Through the New Left, “she had the connections,” Freeman recalled, “and she had the commitment.”17 Shulamith Firestone, who left Chicago for New York a month after the founding of West Side, helped organize the first women’s liberation meeting in New York two months after the Labor Day conference in Chicago. By the next spring, Firestone had prodded the New York group, which took the name New York Radical Women, into producing its first collection of writings, Notes from the First Year. When Kathie Amatniek (later Sarachild), another New York feminist activist, visited Boston, she persuaded her childhood friend Nancy Hawley to join the growing women’s liberation movement. The following year, Hawley was part of an informal women’s group that would write the revolutionary women’s health book Our Bodies, Ourselves.

The Jeannette Rankin Brigade Protest, a January 1968 peace action in Washington, D.C., organized by the West Side Group and New York Radical Women, helped to promote the movement and, in a flier created by Kathie Sarachild, introduced what was to become its trademark slogan, “Sisterhood Is Powerful.”18 The movement was spreading like “wildfire,” commented Ann Snitow, a member of New York Radical Women. “We called ourselves brigades and we founded a whole bunch of other brigades; we cloned ourselves.”19

By April 1968, approximately thirty-five small radical women’s groups concentrated in big cities were on the map; by the end of the first year, there was “hardly a major city” without one or more.20 The groups formed spontaneously, as women sought each other out for support and to discuss specific abuses.21 While focused on general women’s liberation issues, each group reflected the overall emphases of the area in which it formed.22 “New York City is the culture capital. Chicago, heavy industry. We were the edge, you the heartland,” Rosalyn Baxandall of New York City wrote to Naomi Weisstein, pointing to one of the regional differences that shaped early radical feminist groups.23

To create a wider coalition, Marilyn Webb and several colleagues organized the first nationwide gathering of women’s liberationists at Sandy Springs, Maryland, in August 1968. There, twenty participants spent a tense fall weekend arguing about whether men or capitalism was the greater enemy and castigating themselves for the failure to involve black women in the incipient movement. As an outcome of the meeting, Webb, with Laya Firestone of Chicago and Helen Kritzler of New York, organized a conference to commemorate the 120th anniversary of the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls. Due to their efforts, two hundred women came together at a YWCA retreat in Lake Villa, outside Chicago, during Thanksgiving week, but this larger meeting was also wracked by controversies between “politicos” (arguing from the New Left position that women’s oppression derived from capitalism) and pro-woman “radical feminists” (urging an autonomous women’s movement since men were the ultimate oppressors).24

In Chicago, the West Side women wrestled with their allegiance to the male-dominated Left but believed that their group marked an important step away from the masculinist emphases of SDS. After years of being “judged and humiliated” by New Left men, Amy Kesselman exulted in the fact that she had comrades with whom she could openly develop her ideas. But separating from the New Left was extremely difficult—like “divorcing your husband,” she said. Several members of West Side were in fact married to SDS “heavies”: Heather to Paul Booth, a former SDS vice president; Naomi to historian Jesse Lemisch, a member of the original SDS at the University of Chicago and then Northwestern University; Vivian to activist Richie Rothstein.25

Nonetheless, the Chicago women felt that their position inside SDS was “no less foul, no less repressive, no less unliberated” than outside: “We were still the movement secretaries and the shit-workers.”26 They tried to find a balance between the socialist perspectives they shared with male leftists and their conviction that it was essential to challenge male supremacy. The attempt to find a middle ground is reflected in an April 1968 paper, “Toward a Radical Movement,” by Heather Booth, Evi Goldfield, and Sue Munaker, which argued that “there is no contradiction between women’s issues and political issues, for the movement for women’s liberation is a step toward changing the entire society.”27

Yet Jo Freeman believed that more than any other city, Chicago had a women’s movement “bound by the leftist mentality.” Years later, in an unpublished memoir, Weisstein admitted, “our ties to the male New Left really retarded our progress, tied up our creative energies, restricted our freedom in thinking and doing.”28 This view was shared in New York, where radical feminists believed that the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU) women “were under the thumb of the male SDSers.”29 Sara Evans believes that Chicago feminists resisted the divide between the two orientations. Although West Side was “decidedly politico” at first, historian Alice Echols agrees, organizing around such non-gender-specific issues as opposition to the Vietnam War, the group became women-centric.30

As West Side members sought to develop their own political agenda, Kesselman, Booth, Rothstein, and Weisstein looked to each other for “political support and guidance, consulting each other about almost everything [they] did.”31 Each of the four had come to Chicago for different reasons. After Weisstein completed her doctorate in psychology at Harvard, she took a postdoctoral position at the University of Chicago and then, briefly, a faculty position at Loyola University. Rothstein had participated in the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project in 1965 and then went to Chicago to be an organizer with the SDS project JOIN Community Union, to “build a multi-racial movement of the poor.”32 Kesselman, who had become an activist at City College in New York, moved to Chicago because it seemed to her “like the belly of the beast: the perfect place to build a revolutionary movement.”33 Booth studied at the University of Chicago, where she founded the first campus women’s movement organization and started Jane, an underground abortion service that assisted more than eleven thousand women end their pregnancies prior to the legalization of abortion with Roe v. Wade.34

After the creation of the citywide CWLU in October 1969, Rothstein became the organization’s first (unpaid) staff member, responsible for developing a workable structure, and a contributor to many of the organization’s theoretical writings; she inaugurated the Liberation School for Women, which offered skills-based and subject-matter courses relating to women and families. With Weisstein, she organized the CWLU Speakers’ Bureau. Booth helped organize CWLU’s Action Committee for Decent Childcare (ACDC) and brought women into the CWLU to work with Jane. Trained by doctors who had performed the abortion procedure for Jane, after a time, women of the collective began to do the procedure themselves. Kesselman used her background as an SDS organizer to develop CWLU’s workgroups, one of its distinctive features. Weisstein had the idea for the Speakers’ Bureau and, in 1970, created the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band, feminism’s first rock group, which aimed to liberate rock from “sexist evil” and create a “revolutionary women’s culture.”35 Although the band lasted only three years, Weisstein believed that it presented “an image of feminist solidarity, resistance, and power,” offering “absolute democracy, the players and the audience together in a beloved community, . . . a world without female suffering or degradation.”36 The band produced one album, Mountain Moving Day, with two songs written by Weisstein, the title track and “Papa, Don’t Lay That Shit on Me.” Weisstein, who loved comedy and came “this close to running off” with Chicago’s famed Second City troupe, gave the band its distinctive performance style and comic tone.37

The CWLU became a model for sixteen other socialist-feminist women’s liberation groups throughout the country. At its peak, the organization counted fifty core members, with two hundred participating in workshops and chapters and another one hundred members at large. Hundreds of others took classes at the Liberation School, came to the pregnancy-testing clinics, or called the rape hotline; its mailing list reached nine hundred by the end of the 1970s. Most members were young, white, middle class, and highly educated, a pattern typical of women’s liberation groups at the time. As Margaret Strobel discovered in her interviews with forty-six CWLU leaders, the homogeneity of the group extended even further: all but one of her sample were of European descent and included a noteworthy proportion—43 percent—of Jewish women.38 Consonant with its socialist-feminist framework, the CWLU focused on building solidarity with working women, continually attempting to extend its outreach to poor, working-class, and minority women through its service projects and the Liberation School. The large number of Jewish women in its membership went unnoticed, but Jewish women were among those who most vociferously attempted to diversify the organization.

“We Hit the Glass Ceiling on the Left”: The Route to Chicago

Born in 1939 (Weisstein) and in 1944–46 (the others), the members of the “Gang of Four” grew up in the golden age of the “feminine mystique”: Heather Booth in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn; Amy Kesselman in Jackson Heights, Queens; Naomi Weisstein on the West Side of Manhattan; and Vivian Rothstein in Los Angeles. While the messages that they received from their parents were often positive and purposeful, the values of the surrounding society left them, in Kesselman’s words, “feeling alienated from just about everything.” Kesselman absorbed “political consciousness” from her left-activist parents, but “in the fearful atmosphere of the McCarthy era,” such messages seemed “muted and confused.” She became an activist, organizing a high school discussion group even though she was told that “politics, sex, or religion” were forbidden topics. In her senior year, Kesselman was suspended for several days for protesting the civil defense drills that perpetuated the belief that “standing against the wall could save us if a nuclear bomb dropped on New York City.”39

Naomi Weisstein’s high school experience was little better. After two years in an all-girls school, she transferred to the prestigious Bronx High School of Science, and her world “collapsed”: “All my music, my art, my writing, my acting in plays, my power, standing, and popularity, that I enjoyed in the first fourteen years of my life vanished in a day, as it became clear that the only thing that girls were judged on was their ability to negotiate the world of heterosexuality. . . . I can still feel my resentment, rage, and despondency at this state of affairs, especially because it seemed as if my future were closing down on me.”40 Like Kesselman, Weisstein had grown up “in the church of socialism.” Intuitively, she recognized that politics would be a part of what she did with her life, while even in this prefeminist era, she assumed that the domestic “mystique” would not. “I knew that my life could not be devoted to husband and children,” Weisstein wrote in The Feminist Memoir Project, “that I must have a career, and it wouldn’t be such a bad thing if I didn’t marry at all.” But in that “harsh, repressive, and wildly woman-hating decade” (Weisstein was “ten in 1950, twenty in 1960”), she could not openly proclaim her beliefs. Thus, she said, “I was in the closet most of the time on two accounts—my socialism and my feminism.”41

High school also presented a challenge to Heather Booth, whose family moved from Brooklyn to Long Island when she was a teenager. Booth became head of several high school clubs but could not find a way to engage the values of social responsibility passed on by her parents. Like Weisstein and Kesselman, she began protesting even before college, dropping out of the school sorority and one of the cheerleading teams “when it was clear that they discriminated against blacks and girls who did not fit some standard definition of ‘pretty.’” Like the others, she was ready for other meaningful activity.42

As a child of German Jewish immigrants who fled from the Nazis in the late 1930s, Vivian Rothstein’s coming-of-age years differed from those of her friends. Because her parents were refugees from Nazi Germany, she had a “keen sense” that she was a “person potentially at risk”: “they could come after us at any time.” Rothstein acknowledged that it was this fear that led her to gravitate toward other groups at risk: “not just to help them out, but to protect myself.” This feeling, combined with the absence of her father (who had separated from her mother), made Rothstein feel “like an outsider looking into mainstream America.” She, too, was a “ripe candidate” for 1960s activism.43

The moment came soon enough. Amy Kesselman entered City College in 1962, interested in “read[ing] Marx instead of doing homework.” Soon she was president of the campus committee against the war in Vietnam. Yet with her male colleagues, Kesselman felt “stupid and inadequate,” her activism filled with “petty humiliations and frustrations.”44 After college, she moved to Chicago to work with an organizing project with high school students, but she again found herself stymied by male leaders’ hostility to women peers.

Vivian Rothstein became a scholarship student at the University of California at Berkeley, a member of the first generation in her family to go to college. While a student, she participated in mass civil disobedience actions organized by CORE, then dropped out of school to become a full-time organizer, first in Mississippi and then for JOIN Community Union in Chicago. But neither the civil rights nor New Left movement welcomed her as a “leader or as an intellect.” There seemed to be room for her “only as a body going limp in mass demonstrations.”45

Naomi Weisstein flourished in Wellesley’s all-female atmosphere but had a difficult time studying for her Ph.D. in Harvard’s psychology department, where she faced sexism and the “heterosexual juggernaut.” Moving to New Haven for her dissertation work, she joined CORE but was shocked to find that she was terrified to speak publicly. “I didn’t understand it at all,” she recalled. “I didn’t understand it until Chicago, until Heather and I started talking about women’s position in these movements for social change.”46

In 1960, still in high school, Heather Booth joined the effort to aid CORE’s sit-ins to support African American students’ boycott of Woolworth’s. At the University of Chicago, which she entered in 1963, she joined SNCC and went on the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project the next year. In 1965, after learning that a friend from the Summer Project had become distraught over an unwanted pregnancy, she began the Underground Abortion Collective, Jane.47 Booth chafed at the sexism in the student movement around her. At one large meeting, when a male student told her to “shut up,” she did. But, she said, “that was the beginning of our own organization, the Women’s Radical Project (WRAP), which became one of the most dynamic groups on campus.”48

As Vivian Rothstein recalled, “We had hit the glass ceiling on the left and there was nowhere for us to go. We were hungry for political discussion with others who took us seriously, and slowly we began to find each other.”49 Weisstein and Booth met at a University of Chicago sit-in in 1966; they “shared their consternation about how few women were speaking and talked about their own struggles and frustrations.”50 They then co-taught a course at the University of Chicago organizers’ school. The following year, Kesselman met Booth at a draft counseling office. After their first two-hour conversation, Kesselman felt as if she “had been awakened from a deep sleep”: “together we figured things out.” Later she met Weisstein, who was “astounded” by Kesselman’s comments about the importance of agency in people’s lives. “I wanted to talk to Amy forever,” Weisstein recalled.51 Rothstein met Booth at the 1965 SDS conference in Champaign-Urbana, which held the first separate meeting of women radicals. She met Kesselman through the Chicago Organizers Union. In 1967, Booth, Kesselman, and Rothstein came together to discuss tactics for getting involved in justice campaigns.52

“Throughout 1966 and ’67,” Kesselman wrote, “Heather, Naomi, and I talked about what it meant to be female in our society at every possible opportunity. Each time we talked, we generated new insights. The world seemed to be coming dramatically and miraculously into focus.”53 “The best part of the group was that we all took each other seriously,” Weisstein agreed. “We had become so used to the usual heterosexual chill that it was a giddy and slightly terrifying sensation to talk and have everybody listen. All of a sudden we were no longer inaudible . . . the joy! Unbelievable. The sound system had just been turned on. We couldn’t wait to go to meetings.”54 After Rothstein joined the West Side Group, she became the fourth member of the “gang,” the others drawn to her “sense of moral purpose, her intelligence, and her unshakable commitment to organizing.”55

“Our appreciation of each other was like fertilizer,” Kesselman recalled, “liberating energy long stifled by the sexism of the male leadership of the new left.”56 “We were so different,” Booth remembered. “We were so similar. We were so courageous. We were so insecure. We called forth the best in each other. We called forth what we did not even know was there. We were more than the sum of our parts.”57

As the women’s movement spun off other new projects and ideas, the friendship of these four women flourished. There was none of the ambivalence that Kesselman felt about her female friendships at the male-dominated City College, where women seemed to accept their marginality.58 In Chicago, the friends came together to talk, study, organize, and protest, emboldening each other as they joined a larger group to start a feminist revolution. How did they come to take this path together? Did Jewishness have anything to do with it?

Growing Up Jewish: Yiddish Radicals, Jewish Mothers, the Holocaust, and Israel

Growing up Jewish during the years of the postwar feminine mystique influenced each woman’s maturation into left activism and feminism. Despite the lack of any explicit Jewish identification, the influence of Jewish values and experience was significant.

For Amy Kesselman, growing up as the child of secular left-wing Yiddishists was a formative influence on her developing political views.

My parents were . . . communists until the 50s. They had both rejected the religion of their immigrant parents but in the wake of the Holocaust they embraced their Jewish identity as a political act and were determined to communicate a secular Jewish identity to their children. We never went to synagogue except when visiting my grandparents who spent the high holidays at a Jewish Old Age home. But we did celebrate Chanukah and Passover. The menorah always stood at the window to show people in the neighborhood that we were Jews and we sang the spiritual Go Down Moses at our seder. After the war my parents joined with other secular, progressive Jews to organize a “shul” in our community that would teach their children Jewish history, Jewish folksongs and the rudiments of Yiddish, all of which was infused with progressive politics—a hatred of dictators and Jew haters, a belief in struggle. I think the shul achieved its primary goal: making us identify as Jews and to feel a connection with down trodden people. It was less successful in teaching us Yiddish.59

The heritage of secular Jewishness played a role for Naomi Weisstein as well, though her Yiddish skills remained similarly undeveloped. “My mother was very atheist, and her father, my grandfather, who had come from Russia, used to sit on the steps of shul on Yom Kippur, eating a ham and cheese sandwich. They had a sort of positive commitment to secular Jewishness and a rabid anticlericalism. But they did send me to Yiddish school, not Hebrew school, so that I could learn the folkways of my people. I couldn’t stand it because I am very bad at languages. Finally Mrs. Lerner called my mother and asked, ‘Is Naomi retarded?’ My mother took me out. Why pay for this?”60 Although Weisstein identified as a “red-diaper” baby, she commented that given her mother’s anarchist radicalism and her father’s nonpolitical stance, she might more accurately be labeled a “purple and white polka dot baby.” Samuel Weisstein, a lawyer, was dedicated to his clients in Harlem, for whom he worked for “pennies,” but Naomi considered him “racist” in his belief that “black people were poetry” and “childlike,” needing his protection. Then there was the influence of her maternal grandparents, her Menshevik grandfather and Bolshevik grandmother. Because of these forebears, Weisstein acknowledged, “I am infused with the Jewish radical tradition.”61

Also identifying as “secular Jewish,” Heather Tobis Booth absorbed the Judaic values of social justice in her childhood and adolescence. This tradition became a vital lens with which she interpreted the world.

Many of my mother’s family were Orthodox, some Hasidic, and lived in walking distance of each other in Bensonhurst. My mother married someone who was Conservative. When another relative married outside of Orthodoxy, the father sat shiva for the daughter. But my father was going to be a doctor. Also [my mother] was sort of a loved child with many loving members of her extended family. My father’s family was also very loving and close.

My mother became anti–organized religion. But many, many of the elements of Judaism were consciously part of my upbringing, so I couldn’t say where one [part of my identity began and one] ended. . . . I thought being Jewish meant sharing values—believing in freedom and justice and the struggle for freedom itself. The holidays were very important—what is Passover but the struggle for freedom that ends up being successful? This is true for many of our holidays, celebrated in many of our traditions—standing up for what is just and right. Even the Bible says, “justice, justice shalt thou pursue.” Twice it says “justice,” because it is that important.62

Once asked how she got to be the way she was, Booth responded, “some people get to be radicals by having [to] break from the past, whereas we felt very consistent with it.”63

Vivian Leburg Rothstein believed that her “Jewishness played a role” in her “ability to be a critic of American culture and in becoming a feminist.” “My parents fled Nazi Germany and already felt at risk and outsiders in the U.S. So I naturally shared some of their sense of alienation and separateness. Plus I was aware that their European social values clashed with the Puritanical American standards of the general society.”64 For Rothstein, “fear of persecution, separation from mainstream American society, identification with ‘outsiders,’” coupled with “a need to find others who shared [her] story, . . . to coalesce . . . for mutual protection,” propelled her activism.65 Although her apolitical parents did not question much about American life, they were deeply concerned about moral issues, especially “what happened to Jews” and the possibility of fascism. Rothstein absorbed their values and understood the experience of minorities well.66 But as the child of immigrants, with the added stigma of divorced parents, she felt excluded from mainstream American life. At school, she was treated as “something a little odd,” “foreign” and “deprived,” isolated by school administrators. Rothstein’s sister reacted to the same circumstances by becoming mainstream.67 Rothstein became a lifelong radical.

In addition to parental models, the education provided in synagogues and more informally through community centers, camps, and travel impacted the women’s social values. Rothstein’s family went to synagogue for the High Holidays but were not synagogue members. She grew up in the Jewish Center community, “which offered an alternative Jewish life. That way Jewish children could have an identity that was anti-religious but not ritualistic—camps, after school sports programs, etc.” The Jewish Center gave Rothstein a community-based opportunity for Jewish engagement outside temple membership, connecting her to Jewish culture, rituals, and holidays. This was particularly important for young girls not offered the bat mitzvah experience and so lacking the mentoring provided by that training. The center’s focus on community service was equally important. Rothstein learned to function as part of a group and became comfortable in group life, lessons she carried with her to her lifelong work as activist and organizer. For Rothstein, and later for her children, Jewish community centers offered education about Jewish traditions and values without being intensely religious. They became building blocks of identity.68

Rothstein’s involvement in the Labor Zionist camp Hashomer Hatzair, to which she went for about three years, reinforced these experiences. The organization was “actively recruiting and training young people to fight for the state of Israel and be prepared for kibbutz life.” Rothstein described what the Jewish youth learned: “to overcome our fears and be brave (breaking into school grounds, crossing borders with ‘forged passports’); seeing ourselves as fighters who make personal sacrifices for a larger goal.” Hashomer Hatzair emphasized the need to share resources and “take action rather than being acted upon,” introducing Rothstein to the concept of a “movement” and “being part of something larger than [oneself].” Its communal/socialist/Zionist values promoted equality between girls and boys. “I think the place I got my feminism from in terms of the Jewish community was Hashomer Hatzair. . . . Hashomer Hatzair was very radical and had a Sabra mentality; it did not believe in sex roles. We were not allowed to wear lipstick. Equality between the sexes was valued. They taught us to use rifles (never loaded), and to staff guard towers. We were supposed to go to Israel. Our leader wound up marrying an Arab guy. For this left-wing Zionism at the time, Arab culture was considered very cool.”69

Heather Booth was deeply influenced by confirmation studies, a trip to Israel, and her progressive rabbi.

We finally ended up in a synagogue with a very progressive rabbi after some bad experiences. By this point we moved to the North Shore [of Long Island]. The rabbi played a very important role for me and I wanted to be a rabbi. Of course I was told women couldn’t be rabbis (at that time), couldn’t be bat mitzvahed. But I was confirmed, and my confirmation study was the Book of Amos—“let justice flow like a river and righteousness like a mighty stream”—comes from Amos. And we really studied and understood what a prophetic tradition is in order to live by its precepts. And in ’63 to accompany a friend of mine who was going to Israel I lived on a kibbutz in the northern Negev. And supported an Arab who was running for mayor in a nearby city. So the tradition [was] sort of reaffirmed. It was part of who I was and what I believed in. I considered living in Israel, but returned to be part of the civil rights movement in the States.70

Visiting Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust Museum, had a “transforming effect” on Booth. The memorial to Jews who died in World War II was so horrifying to her that she went through profound emotional change. “I promised myself that in the face of injustice I would struggle for justice.”71 “I felt you never go down unless you’re fighting. Never let someone else go down unless you fight for them.”72 “Judaism came to mean that I valued the struggle for freedom and felt tied to a people who had an obligation to continue that struggle.”73

But the peer culture inhabited and shaped by Jewish men clashed with many of the positive values bequeathed by Jewish family and community. Amy Kesselman explained:

As I became involved in politics at male dominated city college, I started resenting Jewish men, who, I told my friends, “had their penises in their heads.” Men asked the five-paragraph questions in the classrooms and dominated the political movements that I was involved in. When women’s liberation erupted in my life, I looked back critically on the dynamics in my family and the way they enshrined my father as the political and intellectual superior whose approval I always sought but never felt that I fully gained. . . . So my Jewishness bequeathed a mixed legacy—a commitment to social justice and anger at the sexism embedded in Jewish culture.74

Role models offered by Jewish mothers were a further source of confusion. Like the influence of family and community life generally, the impact of Jewish mothers was profound, yet it pulled in opposite directions. Some women’s liberationists, such as Vivian Rothstein, whose refugee mother raised her as a single parent, greatly admired and respected their mothers’ examples of strength and autonomy. In these women’s eyes, Jewish mothers seemed more empowered than other postwar females were. Rothstein’s mother offered a different model from the outset, one definitely not defined by the postwar “feminine mystique.” “I grew up with just my mother,” Rothstein explained. “She was the head of our family. She had left my father when I was born. I had great total respect for my mother. I was completely connected to her. I was totally in love with her.” In Rothstein’s opinion, most refugee mothers, such as her own, bore much of their families’ financial burden. “Their husbands had been middle-class businessmen in Europe, like my father, but in postwar America, they were déclassé and couldn’t find similar work. In this community, men were supposed to be the strong ones, but women ran the finances. It wasn’t the feminine mystique model at all.” But although her mother was self-sufficient “to an extent,” Rothstein identified with her “isolation and limited role options.”75

These women’s effectiveness, as well as their nurturing and caring attitudes—“really loving kindness,” as Booth phrased it—shaped daughters’ values and initiated them into the Jewish tradition of social and community concern. Booth elaborated:

I viewed my mother as sort of the mother—the mothering-ing person, which she was—and my father as the intellectual who made activity in the world. My mother’s father believed women shouldn’t go to college. And though she had won a scholarship to go to Hunter—she had been valedictorian in her high school—he told Hunter not to accept her, that he wouldn’t accept the scholarship. So she didn’t go to college until we were in high school. And then got her master’s, became a special ed teacher. . . .

It turns out that she also was an activist as a young person. Before World War II, part of her valedictory speech was a propeace speech. She also at one point worked selling gloves in a store and tried organizing people in the store into a union. I didn’t get that kind of appreciation of her until there was a women’s movement.

Seeing women be active in the world in roles other than taking care of kids and being the homemaker was really exhilarating. For me, my peers, as mentors or at least friends, had at least as strong an influence in terms of feminist activism. But in terms of the values which we learn to live by, my mother (and my father) were very strong influences.76

But mothers’ influence was rarely acknowledged. Booth recalled the 1965 SDS conference in Champaign-Urbana, where at a session on the “women’s issue,” participants shared personal backgrounds, including their motivations for activism. Most talked about family situations in which at least one parent gave them support. For the majority, it was fathers. No one talked about mothers.77

Others of the four Chicago friends felt mainly anger, and sometimes betrayal, at what they viewed as mothers’ subordination to fathers and to men generally. “I really did not want to be like my mother,” Kesselman admitted. “I did not think of her as an empowered person at all. And in my family she was really systematically diminished by my father who had all the brains and the political expertise; I wanted to be like him and discovered that nobody was going to let me do that. . . . There were strong women in the culture that we lived in but they were mainly seen as secondary in the life that mattered. The life of the mind.”78

Naomi Weisstein, as the daughter of Mary Weisstein, her politically radical mother who gave up her career as a concert pianist to raise her family, made a vow: “I would never get married and . . . I would never have kids. I was sure it ruined her life.” Weisstein’s mother had gone to Julliard and studied with Aaron Copland; she was a brilliant pianist who combined her art with politics, performing at socialist and anarchist programs—the highlight of her life was accompanying Paul Robeson at one such event. But all her life, Weisstein’s mother struggled against her husband’s “male supremacy.” Weisstein thought she was never going to be like her mother, “because she gave up.” “She struggled all her life, but she stopped being. That was terrible as far as I was concerned.” Weisstein believed “that she really hated the daughters,” Weisstein and her sister, because they “had destroyed her career.”79

But at the same time, Weisstein recognized her mother’s contributions to their lives. She relished her mother’s stories, especially about her own grandfather, “a Jewish Humphrey Bogart,” the Menshivik from Russia who became an anarchist and union organizer and sat smoking and eating a ham sandwich on the shul steps in New York to show his contempt for religion. Weisstein tells of how this grandfather, a cabinetmaker, encountered anti-Semitism at his workplaces. “At one shop he once took a hand saw and held it in front of him. ‘I hear some of you don’t like Jews,’ he said. ‘Speak up . . .’ He never had trouble there again.” Her mother inherited that spirit, playing piano “like a militant angel come down from heaven to set things right in this world of injustice.” When she died, the strains of Chopin’s fiery “Revolutionary Etude” flooded Weisstein’s head. Despite her mother’s truncated career as a pianist, she did remake herself as a psychotherapist, dispensing a “decidedly unorthodox Freudianism.” Weisstein remembers her standing instruction to her female patients: “Make him give you oral sex.” “The legacy of resistance went from Grandpa, to Mary, to me.”80

The women’s movement provided the context for understanding mothers whose aspirations had been thwarted by the forces of postwar domesticity, even in leftist households. Kesselman had not understood the reason for her mother’s departure from the Communist Party—“because people weren’t nice to each other”—as a substantive political position until feminism enabled her to see that she was criticizing the party’s authoritarianism. She did not understand her mother until feminism made her think “differently about the dynamics” of her family.81

Booth admired her mother’s strong Jewish values and courage but not the limits of her domestic role. When her mother recommended that her daughter, then in high school, read Friedan’s Feminine Mystique, which had strongly influenced her, Booth refused: “I didn’t think of myself as a housewife,” as her mother did. With the rise of the women’s movement, however, Booth “came to understand the incredible strength and . . . real human beauty” that her mother had.82

Weisstein had a similar experience: “When feminism came along, I moved beyond my crude adolescent take instead to really appreciating [my mother] and thinking, my God, what a hard life, trying to continue her music when my father snored loudly whenever he heard it. What had seemed weakness on the part of mothers now became attributable to the inexorable workings of the patriarchy.” At a memorial service for her mother, Weisstein declared her to have been a “true original” whose legacy, a model of “combativeness,” she treasured. Despite the turmoil and conflict, her mother was her “inspiration,” her “call to courage.”83

Kesselman suggested that the characteristics validated by women’s liberation, which included strength, intelligence, toughness, wit, and a kind of brazenness and boldness, might have been especially applicable to the proverbial “sharp-tongued, pushy,” urban—read: Jewish—woman.84 This might well have included mothers.

The legacy of the Holocaust exerted a significant, if silent, influence as well in shaping the attitudes of these radical feminists. “One of the things that influenced my politics in the 1960s was the lesson I drew from the Holocaust, which was the value of collective resistance,” Weisstein declared in the group’s discussion of this issue with me. “I’d always been a resister. But the idea . . . that you needed collective resistance to change the world and change the way things work, that occurred to me more after I started thinking about the Holocaust.”85

Rothstein concurred. “I was affected in the way in which I understood the progressive forces, particularly in Germany, could not coalesce against the Nazis.” Rothstein found that college friends on the left were in fact hostile to German Jews for not fighting back. It shocked her that such people “had no understanding really of what people went through and what they lost and really no sympathy.” For years, she stopped talking to activist colleagues about her parents’ experience. “It wasn’t very safe.”86

Awareness of the Holocaust was part of Booth’s background as well. She saw the numbers written on the arm of her uncle Pinkus, and she thought not only about the terrors of the Holocaust but also about resistance. She felt “it was part of a long continuum of what . . . Jewish history was, a struggle for justice in the face of injustice.”87

Kesselman did not tie the experience of the Holocaust to resistance and struggle, but nonetheless, her sense of herself as a Jew of eastern European heritage included awareness of seventeen family members who died in the concentration camps. After the war, her parents had a heightened sense of Jewish identity and sent Kesselman to a secular yiddishkeit shul.

In addition to the traditions, experiences, and attitudes of Jewish family and community, then, beliefs about the Holocaust played a role in shaping these women’s notions about protest and collective action. A consciousness of oppression, the strong pull of social justice ideals derived from Jewish values, and a sense of themselves as outsiders, often alienated from the general culture, provided the Gang of Four with the ability to view women’s condition critically and helped to galvanize their commitment to work for radical change. The women’s movement provided insights that were crucial.88 In so doing, it helped them move beyond the lessons of postwar female subordination to create new identities as empowered women.

“We Never Talked about It”: Jews in the Feminist and New Left Movements

As Weisstein framed it in our group conversation, “even though our families were dissenting Jews, Jewish values permeated our lives.” Yet this influence went unacknowledged. As Weisstein put it, “we never talked about it.”89

Several reasons explain this silence. For example, Weisstein suggested that there was a tacit agreement to ignore the substantial presence of Jews in the New Left and women’s liberation. Any undue attention might well have compromised the notion of universality. “Our holding back about our Jewish backgrounds related in part to a general approach to Jewishness that was widespread in the New Left,” Weisstein said. “I had grown up in the hothouse of New York City Red Diaper Baby politics—for me this included participation in the Young Communist League and the Bronx High School of Science Forum—and when the New Left and then feminism began to emerge, we wanted to build a broader movement than those we had grown up in, and wanted to convey that our new movements were not just a repeat of the Old Left, which we identified, I think correctly, as disproportionately Jewish.”90

Like Weisstein, Kesselman rejected “the creation of separate communities, the fierce defense of ‘our kind’ of people, blind loyalty to a group.” She recalled, “I have a vivid memory of sitting in my parents’ kitchen in my senior year in high school while my mother listened to the radio. Someone was reading the list of all the winners of merit scholarships in New York City. My mother was counting the number of Jews and cheering for each Jewish name. I found it deeply disturbing and in contradiction to what I thought we all believed in—the desire for all people to excel.”91 This “antipathy to tribalism,” Kesselman suggested, represented a strong element in the politics shared by the Gang of Four and others who worked toward building a “larger and more diverse movement.”92 “Our identification with the outside world, in opposition to our parents’ narrow (and self-protective, fearful) views,” added Rothstein, “was rebellious and progressive, . . . a response against the broader society’s divisions by ethnicity and religion. Why would we identify ourselves as Jews when we wanted to promote a vision of internationalism and interfaith and interracial solidarity?”93

Despite the friends’ rejection of the particularism they identified with ethnic identity and their silence about their own bonds as Jews, they suspected that Jewish women were highly represented among women’s liberationists. “If you compare NOW and women’s liberation,” Rothstein observed, “you will see a much greater percentage of Jewish women in women’s liberation. This is probably because they came out of the Left and from large urban centers. They also drew on a legacy of immigrant culture, where as outsiders, it was easy to be critical. Criticism was encouraged in Jewish culture. My mother used to say that there was no Jewish pope—no authority to dictate—and therefore everyone has her own relationship to God. Judaism encourages independent thinking. To be critical is not blasphemous but the basis of the religion.”94

Booth agreed that Jewish women may have been even more disproportionately represented in the radical feminist movement than they were in liberal feminism. For Booth, strong moral, often religiously based values may have explained the presence of Jewish women in both branches of feminism, as it did for many Catholic feminists.

Nevertheless, as Weisstein pointed out, “the obvious Jewishness, both on the left and in women’s liberation, was suppressed. We didn’t talk about it. . . . It was so embarrassing to have so many Jews around, since Jews weren’t the workers who built the garrisons.” But, she added, “of course they were. . . . It was sort of a whiff of anti-Semitism. There was even a silent agreement that we didn’t bring it up because it was counter to the universalist vision of that time. At least I was a little defensive about having so many Jews around.”95 As Weisstein noted, this defensiveness about Jewish origins was a product of the ideology of universalism that was characteristic of many New Left groups at the time, not just women’s liberation.

Negative stereotypes about Jewish women permeated the Left and counterculture, making it even harder for radical women to identify as Jews. Weisstein recalled an incident when, while a doctoral student in Harvard’s graduate psychology program, gurus Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert handed out magic mushrooms. Many students became delusional; Weisstein had a paranoid nightmare and hallucinated for a month. “We knew you would,” Leary commented. “You’re an uptight Jewish female who can’t let herself go.” Weisstein called them “sleazeballs.”96

Others noted the Jewish presence in the feminist movement in negative ways. Booth recalled, “Amy and I were teaching in a high school with another friend, Robin Kaufman. Tobis and Booth were not Jewish-sounding names, but Kesselman and Kaufman were. The principal, who we think had been in the Greek Partisan army for the Nazis, always got us confused and treated us the same way. We all looked different but we were all Jewish. Finally we were all fired in different ways.” While at the time they did not discuss the reasons for the dismissals, they suspected anti-Jewish prejudice. The principal was against almost everything they did.97

Stereotypes about Jews were manifold in the communities where the women worked and volunteered. None of the community people whom Rothstein worked with as organizer in the poor neighborhoods of uptown Chicago believed she was Jewish because she was not rich. The only Jews that residents knew were wealthy landlords.98

In addition to discrimination, negative stereotypes, and internal silencing, the difficult political climate for American Jews in the late 1960s played a part in minimizing radical activists’ self-conscious identification as Jews. The first women’s liberation groups formed a few months after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. For most American Jews, Israel’s military victory signified a source of deep pride, even among young Jews strongly identified with the antiwar and civil rights movements. But some progressive Jews condemned Israeli military actions.99

Kesselman did not speak out, but when she took a job at the Chicago Jewish Community Center’s day-care center in the midst of the war, she felt she had to “lie about what [she] thought.” She speculates now that had she identified more explicitly as a Jew, she might have used her Jewish identity more politically, taking on issues that troubled her within the Jewish world.100

Rothstein also cited the politics of the established Jewish community as a reason for avoiding Jewish identification. When she returned from her trip to North Vietnam in the summer of 1967, she had to earn back the money she borrowed by doing speaking engagements. Although she spoke in churches of every denomination, not one synagogue invited her. Acknowledging Jewishness would have made little difference, Rothstein believes, for she was unsure whether at that moment, there was a place for radicalism within the Jewish world. As the child of immigrants, Rothstein had a further reason to avoid Jewish identification. People on the left “hated German Jews,” she explained; they thought that German Jews should have fought back and resisted the Nazis. “So I just didn’t really talk about it. It wasn’t very safe.”101

“All of these reasons for not speaking about [the fact] that we were Jewish when we were so Jewish!” Booth exclaimed at the “Women’s Liberation” conference. But while the Jewish influence on their activism was not explicit, it definitely impacted these women’s lives. Rothstein summed up her own experience this way: “It’s become clear to me that [my Jewish background] is what largely propelled me into activism.” Although Kesselman is still ambivalent about her own Jewish identity, she acknowledged that Jewishness might well have played a role in the women’s friendship and in the movement. “The four of us shared . . . a belief in a broad and inclusive movement,” she recalled at the conference. “What we appreciated in each other were things like a spirit of inquiry, a desire for intense conversation, and all the things the people have been identifying as characteristic of Jewish culture.”102

West Side member Evi Goldfield concurs, suggesting that the large Jewish participation in the group might be explained by the “largely unconscious affinity for certain personalities to group together and understand one another.”103 Although this factor may have played a role in drawing the women together, their Jewish backgrounds remained under the radar for decades. For feminist friends who discussed almost every personal and political topic, this inarticulateness about a significant feature of their backgrounds remains striking.

The Gang of Four, CWLU Sisterhood, and Its Decline

The friends became an influential political cohort, “the spine behind the inception and first four years of CWLU,” in Weisstein’s words.104 The CWLU was a political organization but had service projects such as clinics and co-ops to help women meet their needs, offering training through workshops and schools. The idea for the group came from a trip to North Vietnam that Rothstein had taken in late 1967 as part of a peace delegation in which representatives of the Vietnamese Women’s Union explained how they were organized from the village to the provincial and national levels. Rothstein described the Vietnamese Women’s Union to the West Side Group, and it became the direct model for Chicago’s socialist-feminist CWLU.105

As an “explicitly radical, anti-capitalist, feminist . . . organization committed to building an autonomous, multi-issue women’s liberation movement,” the CWLU was unusual among women’s liberation groups because of its formalized structure, consisting of workgroups, a steering committee, and semiautonomous chapters.106 While other organizations preferred a loose (or nonexistent) structure, a phenomenon that Jo Freeman labeled the “tyranny of structurelessness,” the CWLU established provisions for regular elections, meetings, and communications, providing accountability through rotating steering-group membership, shared chairmanships, planning committees, citywide forums, and elected leadership.107 Under Rothstein’s direction, it developed leadership training for members, priding itself on its commitment to maximum involvement in decision making both among the chapters, which were devoted to consciousness-raising, and at the project level. In Rothstein’s view, the CWLU’s inclusionary structure demonstrated a vision of feminist pluralism that influenced organizational practice. The decentralized nature of the CWLU reflected a unique feminist structure.108

In a study of the seventeen socialist-feminist unions formed between 1969 and 1975, sociologist Karen Hansen found the CWLU more aligned with women’s projects (e.g., abortion counseling, a rape crisis hotline, a women’s graphic collective, the women’s rock band) than with the socialist politics that characterized most socialist feminist unions.109 For many years, the organization escaped the factionalism that beset most of these unions. In 1972, Rothstein conjectured that the lack of sectarianism resulted from the fact that although the CWLU was structurally innovative, it was not on the theoretical cutting edge: it was “never in the vanguard in terms of ideas, situations, or life-styles.” As opposed to New York, no theoretical breakthroughs came from Chicago: “We didn’t figure out very early about sexism, about violence toward women, about nuclear families, and so forth. But when these breakthroughs finally arrived in Chicago, they didn’t appear in the form of ultimatums.”110 She added another reason the CWLU was not in the theoretical vanguard: “We existed in a very much more oppressive city with a very oppressive political and cultural milieu. We were also in an organizing culture which was strong and which trained many of us to outreach to others, to provide service and engagement and to build organization. It wasn’t a city of writers and intellectuals but of activists and organizers.”111

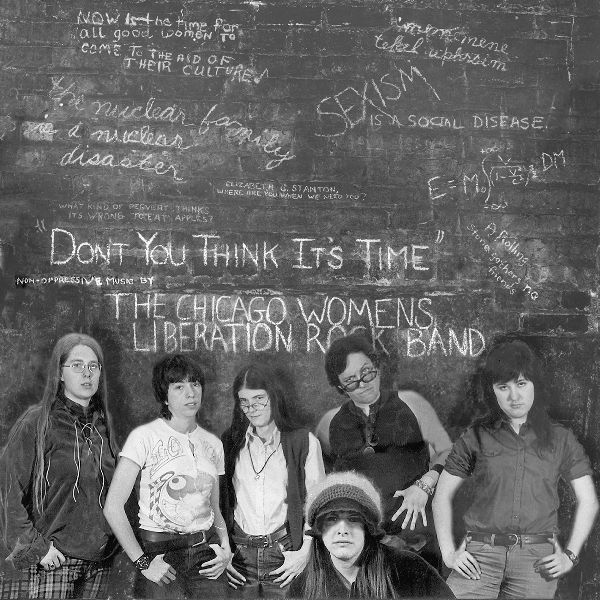

Figure 1.1. Naomi Weisstein (second from left), with the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band, 1971. Courtesy Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band and Virginia Blaisdell.

Nonetheless, the CWLU faced sectarian takeovers (from the Socialist Workers’ Party, the Revolutionary Union, the Communist Workers’ Party, the October League, and others). It disbanded in 1977 shortly after expelling a leftist sectarian group, surviving longer than any other socialist-feminist union, with the exception of the Baltimore Union.112 According to Weisstein, “sectarian mayhem”—the “dogmatism, purification, and relentless obsession” with narrowing the CWLU to politically appropriate members—was a primary reason for the organization’s death.113

Figure 1.2. Heather Booth and her son at women’s liberation march, Chicago, May 1971. Photo by Jo Freeman.

“Trashing”—the movement’s denunciation or silencing of leaders as elitist—affected the CWLU as it did other women’s liberation organizations. Jo Freeman, whom Susan Brownmiller described as “the odd woman out” among West Siders, found herself excluded from meetings of the West Side Group early on.114 Freeman left Chicago in 1968 and wrote “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” “Trashing,” and “The Bitch Manifesto” about the problems of leadership in the movement.115 Weisstein acknowledged that the “tyranny of structurelessness” was a brilliant insight, regretting the outcome of Freeman’s experience in the West Side Group.

Weisstein herself suffered from the “trashing” that silenced so-called undemocratic feminists who moved into the limelight. She had come under attack from the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band because she had become its “mother, . . . its de facto leader.” She was trashed when band members refused to stand up to a growing dogmatism about elitism. But the band died three months after Weisstein left the city. She explained her view of the reason: “we were not honest about the skills we needed to develop and because trashing had replaced compromise and generosity as the dominant political modus operandi of the radical women’s movement.”116 At the time, however, committed to a “deeply utopian egalitarianism,” Weisstein went along with the practice. “People didn’t want to recognize that there were enormous differences in individual talents, abilities, gifts. I spent years trying to appease other women in the movement, trying to be less powerful, so they wouldn’t hate me.”117

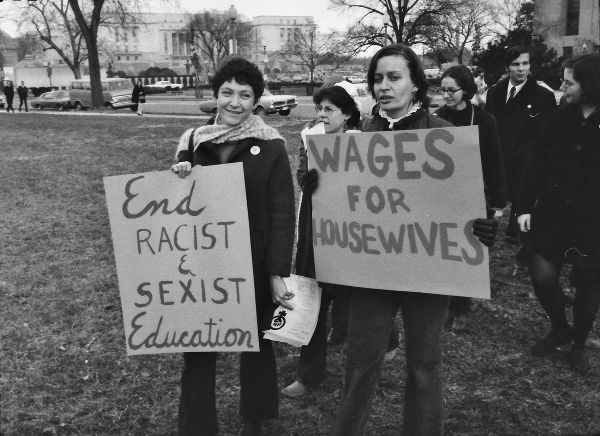

Figure 1.4. Vivian Rothstein (on the left) at a demonstration outside the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Washington D.C., November 1969. Photo by Jo Freeman.

Figure 1.3. Amy Kesselman at a demonstration in Chicago against street harassment, March 1970. Courtesy Amy Kesselman.

As coordinator of the CWLU, Rothstein was the target of criticism from different groups of feminists because of ideological issues. There was no specific targeting of Jewish women within the CWLU, but some women’s liberationists ruminated that Jewish women may have been unequally affected by trashing in several cities because of their strong roles in the movement and their outspoken styles of participation and leadership.

Conflicts between the “politicos” and pro-women’s arm of the women’s liberation movement also took its toll on the friends. As the sectarian rifts within the women’s movement and on the left grew more strident in the early 1970s, the group bemoaned the loss of community. According to Booth, the women’s movement had moved away “from the sisterhood of the earliest years to increasing battles over the meaning of ‘true feminism.’ There was a harsher edge to the political conversations.” More time was spent in meetings on discussions about the “correct position” and less on outreach and mobilization. The CWLU moved away from its early focus on “direct action, non-sectarianism, and a sense of loving sisterhood.”118

Despite the disappointments of movement politics, including tensions among themselves, the Gang of Four was indelibly transformed by the Chicago women’s movement. Movements needed to be “wild [and] anarchic,” Weisstein commented; she would “do it all again.” “We changed a lot of women’s lives, just as feminism transformed [our lives] forever. Those who lived through those early years were transformed in the visionary ways you see in the early parts of . . . movements,” such as the early Russian Revolution. In Weisstein’s view (though not necessarily the others), she became the “passionate brilliant orator,” Booth “the world’s best activist,” Rothstein “the world’s best organizer,” and Kesselman “the world’s most brilliant theoretician.” “What transformed us was a deeply resisting, deeply visionary organization and movement transformed by our righteous indignation, transformed by our compassion and hopes for the future, transformed finally by a group of women who, at a particular time in history and under particular social circumstances all acted much better than we ever thought we could.”119

Rothstein spoke for the group when, in 1973, she wrote to Kesselman, “It is so hard—when we once felt we were making history and the lives of hundreds of people were dependent on our actions—to resolve ourselves to less significant and far less ambitious work. . . . Now that I don’t feel I’m making history, I don’t know exactly what to do with my life.”120

After the CWLU

In Chicago, the Gang of Four worked together for only a few years; all left the CWLU before its 1977 collapse. After Kesselman came out as a lesbian, she felt isolated, with her three closest friends all married. She left Chicago in 1970 to live in a women’s commune in San Francisco. After her departure, a “profound sense of loss” permeated the group. Kesselman felt she “had lost [her] political home” and never again felt as “personally and politically close with any group of friends.”121

The women took different paths after Chicago, struggling to find their own ways. In their late twenties and early thirties, the women were uncertain about their identities and felt “easily judged, hurt, or abandoned by each other.” 122 But twenty-five years later, as the Gang of Four wrote their essay together, they felt the connection they had experienced earlier and the exhilaration of their joint commitment to radical feminism. Each had gone on to make outstanding contributions to feminism and to social change efforts. Part of a group of women’s liberationists who pioneered feminist research and teaching, Kesselman and Weisstein made their mark in women’s studies, one of the most important offshoots of early radical feminism. Rothstein and Booth continued their activism as organizers.

After Chicago, Amy Kesselman helped to develop women’s studies programs on the West Coast and received a master’s degree in history from Portland State University. She taught women’s studies at various colleges in the Portland, Oregon, area, then enrolled in a doctoral program in history at Cornell University, where she wrote her dissertation on women who worked in the Portland-area shipyards during World War II. Kesselman taught in the Women’s Studies Program at the State University of New York from 1981 until her retirement in 2012. She is the author of Fleeting Opportunities: Women Shipyard Workers in Portland and Vancouver during World War II and Reconversion and a co-editor of several editions of Women: Images and Realities: A Multicultural Anthology, widely used in introductory women’s studies courses. She is working on a book about women’s activism in New Haven, Connecticut.

Naomi Weisstein left Chicago in 1973 for a position in the Psychology Department at the State University of Buffalo. By that time, an article that she published in 1968, “Kinder, Kirche, Kuche as Scientific Law: Psychology Constructs the Female,” which criticized the field of psychology for failing to understand women’s experiences, was widely circulating in the women’s movement. In 1970, with Phyllis Chesler and others, she founded American Women in Psychology, which became an important division of the American Psychological Association. This group and her article, reprinted over forty-two times in six languages and the subject of a Festschrift on Weisstein in 1993, helped to establish the field of women in psychology. Weisstein published over sixty articles for leading scientific journals, including six in the highest-level journal Science. Her research highlighted the active role of the brain in making sense of visual input, interpreting what comes in. Throughout her career, she battled the sexism that she experienced in universities and the scientific establishment and expertly outed it to a larger public. Despite chronic fatigue syndrome, diabetes, and other illnesses that kept her bedridden for over thirty years, Weisstein remained involved in scholarship, criticizing what she saw as an increasingly conservative bent in the field even among feminist psychologists, until her death in 2015.123

After leaving Chicago for Denver in 1974, Vivian Rothstein worked with the American Friends Service Committee on its Middle East Peace Education Program and later with Planned Parenthood through the North Carolina Coalition for Choice. In 1982, she moved with her family to Los Angeles, where she was community liaison officer for the Santa Monica city government. From 1987 to 1997, she directed the Ocean Park Community Center, a nonprofit agency providing shelters and services to homeless adults and youths and battered women and their children. Rothstein became involved with and then led the Santa Monica Living Wage campaign, aimed at the city’s low-wage hospitality industry. Working with the hotel workers’ union, UNITE HERE, and the L.A. Alliance for a New Economy, she spent the next eighteen years organizing community allies to bring livable wages and health benefits to primarily female low-wage service workers in the region’s tourism industry. In organizing, “you were at the back, helping people find their voice,” said Rothstein. “It is a “holy profession.”124 Rothstein continued the interfaith work she had begun in the civil rights movement throughout her career, serving on the board of Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice for many years. She was also engaged with the Progressive Jewish Alliance in Los Angeles (now called Bend the Arc).

Heather Booth describes her more than fifty years of activism with words that resonate with Rothstein’s: “If you organize, you can change the world.”125 Booth remained in Chicago the longest. In 1973, she founded and became the president of the influential Midwest Academy, a grassroots, activist-organizer training school in Chicago, its mission to create an army of activists working for change on the local, state, and national levels. The Midwest Academy is a focus for Booth’s efforts to “expand the space of democracy and civil participation” in society, but she has worked on many other fronts, managing political campaigns, including Carol Moseley Brown’s 1992 Senate campaign, and serving as training director of the Democratic National Committee and director of the NAACP National Voter Fund. She was the lead consultant for the founding of the Campaign for Comprehensive Immigration Reform and was the director of the Health Care Campaign for the AFL-CIO. Booth also served as the founding director of Americans for Financial Reform, fighting to regulate the financial industry, and now consults with the Voter Participation Center, one of the largest voter-registration and get-out-the-vote organizations. Within the social change community, her influence is mythic. According to one colleague, at any progressive political event in Washington, D.C., where Booth has lived for several decades, it is easy to find someone of any age who would say, “I’m here because of Heather Booth. She taught me how to do this, she recruited me, she inspired me.”126

Working with so many different political and cultural groups, Booth was surprised when a friend remarked to her that without naming it as such, so much of her world had been the Jewish social action world. Booth recalls that by the early 1970s, she had moved away from the Jewish community, not connecting it to her social justice organizing, but she reengaged a decade later, when as the deputy field director for the Mayor Washington Campaign in Chicago, she “saw anti-Semitism rear its head” in the city and reacted. She also began to connect with a Jewish feminist group that was then developing. By the early 1990s, Booth was becoming more directly involved with Jewish social justice work along with other political and activist involvements. With Leonard Fein and a few other Jewish social activists, she started Amos: The National Jewish Partnership for Social Justice, designed to move social justice to a more central role within the Jewish community. Amos was the prophet who had so deeply inspired her during her teenage years. In 2000, Booth became acting director of the organization. Though Amos closed in 2002, Booth has taken heart in the continuing flowering of social justice action work within the Jewish community; she and Rothstein are the two members of the group of friends to have worked directly with Jewish groups. In Booth’s own life, the commitment she made in 1963 at Yad Vashem is still ongoing: “in the face of injustice, I would work for justice / tikkun olam.”127

Marilyn Webb: Jewish Identity and the Widening Networks of Women’s Liberation

Marilyn Salzman Webb, who had been involved in the civil rights and New Left movements, represents the wider group of Chicago radical feminists for whom religion and ethnicity were unimportant, unspoken dimensions of activism. Starting in Chicago, Webb went on to organize the Washington, D.C., women’s liberation collective and founded the feminist journal off our backs.

Webb rightly deserves a place in the honor roll of radical feminist foremothers. Born in New York City to a lower-middle-class Jewish family, Webb graduated in 1964 from Brandeis University, where she had been a scholarship student, and went on to study educational psychology at the University of Chicago, receiving a master’s degree in 1967. She started one of the first Chicago preschools for the children of poor women, which she directed for three years. At the same time, she directed a second preschool at Saul Alinsky’s community organizing project, working with mothers on welfare. “I learned to be a woman from them,” Webb said.128 In Chicago, she joined SDS, the organization’s new headquarters, and met SDS national leader Lee Webb, head of SDS’s Vietnam Summer Project, whom she married. Webb’s close ties to the New Left’s male leadership mirrored those of Rothstein, Weisstein, and Booth, with whom she started an early women’s liberation group that met briefly after the 1965 SDS Champaign-Urbana conference.

Webb organized several events that galvanized New Left women activists and that helped spawn a new women’s movement. In January 1969, she attended the catastrophic counter-inaugural rally organized by the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam (Mobe) to protest Nixon’s second-term swearing-in. Webb had been invited by Mobe to address the rally, but because she was identified with an SDS-friendly women’s liberation perspective, Shulamith Firestone demanded that she speak on behalf of women advocating a clear break with the Left. Highlighting women’s oppression within the capitalist system, Webb began her speech. Historian Ruth Rosen describes the moment: “Suddenly pandemonium broke out in front of the stage. Webb plunged on, denouncing a system that treated women as objects and property. To her horror, she watched as ‘fist fights broke out. Men yelled things like “Fuck her! Take her off the stage! Rape her in the back alley!”’ . . . Shouts followed, like ‘Take it off!’” “It was absolutely astonishing,” Webb recalled, “and this was the Left.”129

Firestone grabbed the mike. “‘Let’s start talking about where we live, baby,” she shouted. “Because we women often have to wonder if you mean what you say about revolution or whether you just want more power for yourselves.”130 Men in the audience booed and yelled out obscenities; the atmosphere was frightening. Although Webb recalled some men in the audience trying to silence the hecklers, she was shocked that longtime antiwar activist Dave Dellinger was not one of them and in fact told her to “shut Shulie up.” “If radical men can be so easily provoked into acting like rednecks,” proclaimed Ellen Willis from New York, another Jewish-born women’s liberationist, “what can we expect from others?”131 “A football crowd would have been . . . less blatantly hostile to women,” Firestone wryly observed.132