4

Our Bodies and Our Jewish Selves

The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective

On May 11, 1969, Nancy Miriam Hawley stood in front of a small group of women at Emmanuel College, leading a workshop titled “Women and Their Bodies” at Boston’s first Female Liberation Conference, which she had organized with Roxanne Dunbar of Cell 16. Like Hawley, who had recently given birth to her second child, a number of women at the workshop who had been involved in the New Left and the new women’s movement were having babies. “Birth control and children were prominent issues for us,” Hawley recalled.1

The session caught fire when Hawley recounted a remark made by the obstetrician who had delivered her daughter a few weeks earlier: “He said that he was going to sew me up real tight so there would be more sexual pleasure for my husband.”2 Outraged participants told of their own experiences with demeaning and sexist doctors. The group quickly came to realize that they should continue to meet to share information, including a list of doctors whom the women felt they could trust.

As the summer passed, the list kept growing smaller, with negative information about so-called trusted doctors continually surfacing. The women began to develop their own reports on topics about women’s health. Calling themselves the “Doctors’ Group,” they began meeting in each other’s homes to prepare a course on the subject.3 “At the time, there wasn’t a single text written by women about women’s health and sexuality,” said Hawley. “We weren’t encouraged to ask questions, but to depend on the so-called experts. Not having a say in our own healthcare frustrated and angered us. We didn’t have the information we needed, so we decided to find it on our own.”4 In the fall, they put together a twelve-session course on women’s health issues, held at a lounge at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). On the basis of what they had learned in the course and because requests came in from women’s groups, they reworked their ideas into a 193-page stapled newsprint booklet, called Women and Their Bodies: A Course, which was published by the New England Free Press.5

The women published a revised copy of the booklet in 1971 through the auspices of the nonprofit New England Free Press. Rejecting the alienating third-person pronoun “their,” they called the new booklet Our Bodies, Ourselves, putting themselves at the center of the project.6 Like the new title, the introduction emphasized the collective nature of the endeavor to build a new movement based on women’s gaining control of their own bodies. This newsprint edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves made feminist and publishing history, with 250,000 copies of the booklet sold largely by word of mouth and through a substantial network of alternative bookstores.7

In 1972, the group of a dozen women formally incorporated and became the founders of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective (BWHBC).8 The collective published its first commercial edition with Simon and Schuster the following year. The volume provided a strong basis for empowering readers through new knowledge and strategies for self-help; subsequent editions provided additional materials and reflected changing foci. The seven sections in the revised 1984 edition—“Taking Care of Ourselves,” “Relationships and Sexuality,” “Controlling Our Fertility,” “Childbearing,” “Women Growing Older,” “Some Common and Uncommon Health and Medical Problems,” “Women and the Medical System”—were less medically oriented than in the 1973 book: “more focused on what we as women can do for ourselves and for one another.”9 All royalties earned went to sustain the organization’s modest payroll for work on the book and for grants for feminist projects.

In 1976, by which time Our Bodies, Ourselves had sold an astonishing two and half million copies, it was named as one of the ten all-time best books for young people. It remained on the New York Times best-seller list for almost three years. In Europe, the book became one of the first books to become a best-seller in translation from English. By 2010, over four and a half million copies had been sold, printed in more than twenty-five languages.10 Now in its ninth edition, the book is widely recognized as the bible of the women’s health movement. “We didn’t set out to transform the global conversation about women’s health,” said Nancy Miriam Hawley, “but that’s what we had a part in doing.”11

Like other women’s liberationists in Chicago, New York, and Boston, most of the founders who produced Our Bodies, Ourselves had participated in civil rights, student, peace, and welfare rights groups before they came to the women’s movement. As they began to inform themselves about the patriarchal culture that constrained women from making informed medical choices, the common cultural history wrought by their advanced education and their immersion in the civil rights and New Left movements deepened their consciousness of the impact of gender inequality on their lives. Being on the “cutting edge politically,” as founder Wendy Sanford put it, led them to place issues of women’s health within a larger, systemic critique of capitalism and sexism.12 The collective aimed to promote social programs that would “reduce people’s need for expensive medical interventions and work for deeper social changes which will help eliminate poverty and racism.”13

The collective believed that giving women access to information about their own bodies would allow them to make choices about health care and diminish the medical establishment’s stronghold over women’s lives. A key instrument of this revolution would be readers organizing CR groups, as the BWHBC did itself, around issues in the book. By the time of the publication of the 1984 edition, the founders group had been meeting together once a week for twelve years.14 Its feminist values included eschewing the traditional male-dominated organizational model, often derived from establishment practices such as Robert’s Rules of Order, and inventing its own governance, work, and financial management standards.15 In its structure and methods as well as its mission, the BWHBC was a radical endeavor.

Although the BWHBC operated out of Boston, with strong ties to the Boston women’s movement and the Boston Left, it quickly exerted national influence. The relative lack of tension between “politicos” and radical feminists in Boston nurtured the collaborative spirit of the group. Several members were involved in Bread and Roses; others participated in different feminist consciousness-raising groups or in varied New Left projects. The development of collective authorship as the group’s means of evoking feminist change benefited from the unusual connection between personal consciousness-raising and political organizing in that city.16

The BWHBC became a fulcrum for the burgeoning women’s health movement, providing a model of consciousness-raising and consumer advocacy that questioned traditional, male-dominated medical practices. Working with women’s health groups throughout the country, it fought for the legalization of abortion and helped the 1975 launch of the National Women’s Health Network as the “action arm” of the women’s health movement, hoping to influence policy in Washington, D.C.

While most radical feminist groups from the late 1960s and early 1970s have long since disappeared, the BWHBC not only has survived but has grown in outreach and coverage. The book has been adapted throughout the world, with teams of women in at least twenty-five countries selecting and editing the material according to local needs. In 2011, Our Bodies, Ourselves celebrated its fortieth anniversary with a new edition of the book and a symposium that included representatives of its partner organizations from Armenia, Bulgaria, India, Israel (representing Jewish and Palestinian communities), Japan, Moldova, Nepal, the Netherlands, Puerto Rico, Senegal, Serbia, Tanzania, and Turkey.17

One of the factors that distinguished the BWHBC from other women’s liberation collectives was that except for three of the original founders, all members were wives and mothers. Several knew each other from children’s or mothers’ groups or connections forged by their husbands’ work or schooling. Wilma (later Vilunya) Diskin knew Hawley from a mothers’ group. Her husband was an MIT colleague of Hawley’s husband, as were the husbands of Pamela Berger, Ruth Bell, and Jane Pincus. Pincus joined the summer group because she knew Hawley from their children’s playgroup and Diskin from a tots swimming class. Wendy Sanford and Esther Rome’s husbands were in architectural school together. Paula Doress-Worters gave birth to her second child shortly after the Emmanuel conference. Joan Ditzion, wife of a medical resident at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, had her first child several years later, as did Rome. In addition to these nine women, the founders group included Judy Norsigian, twenty-three, the youngest member, and childbirth educator Norma Swenson, forty, who came on board in the fall of 1971. Norsigian, not yet a mother, and Swenson, who had older children, gave more time to the collective’s work, including travel, interviews, and collaborating with other organizations. They became the public face of the BWHBC.

Scholars who have written about the BWHBC note that its original membership was highly educated, predominantly middle class, and white, factors that promoted cohesion but also sameness. Although the founding group’s racial composition is seen as significant, its Jewishness remained invisible.18 Yet of the twelve original founders, eight were Jewish (the total number includes one founder who moved to Canada and left the collective after the first year).19

The Jewish stories of the founders of the BWHBC must be viewed as constituents of a larger portrait of Jewish and feminist identities that shaped the social change movements of the late twentieth century. In historian David Hollinger’s view, understanding the Jewish-related characteristics of “dispersionist” groups such as the BWHBC is also key to a much broader conception of American Jewish history, one that goes beyond a focus on Jewish-identified “communalist” groups whose connection to Jewish life is explicit.20

This chapter tells the Jewish stories of six Jewish founders of the BWHBC and three non-Jewish founders, whom the group’s Jewishness also influenced.21 Despite racial and class privileges, as Jews, these members inherited specific values and outlooks of a minority culture, which had repercussions for the BWHBC’s organizational life. The legacy of Judaism, which included pride and critical thought as well as marginality, contributed to the content and approach of Our Bodies, Ourselves, encouraging innovation, antiauthoritarianism, and self-help. These factors combined with the perspectives and heritages of non-Jewish founders, which played an important role as well in shaping the BWHBC.

The narratives of the Jewish founders follow the pattern of Jewish women in liberation groups already discussed in Chicago, New York, and Boston, which developed consciousness-raising and action agendas pertaining to women as a universal group, with issues relating to ethnicity and religion rarely surfacing. Despite these groups’ considerable proportions of Jewish women, Jewishness was not a topic of discussion. Yet it was meaningful in the women’s personal lives, serving as a backdrop for social activism, intellectual concerns, ethical values, and community building.

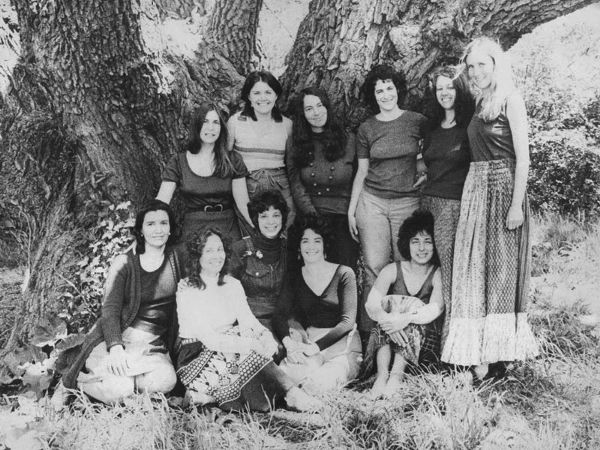

Figure 4.1. The founders of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. Back row: Jane Pincus, Vilunya Diskin, Joan Ditzion, Esther Rome, Paula Doress-Worters, Wendy Sanford. Front row: Norma Swenson, Pamela Berger, Ruth Bell Alexander, Miriam Hawley, Judy Norsigian. Photo by Phyllis Ewen.

In women’s liberation groups in these cities, members’ varied Jewish backgrounds included red-diaper and secular influences, religious and traditional components, connections to the Holocaust and anti-Semitism, and experiences of marginality. All of these factors shaped the coming of age of the Jewish founding members of the BWHBC as well. But the collective was the only one of the organizations discussed thus far that included an observant Jew, another who had gone to an Orthodox day school, and a third woman who had been a child survivor of the Holocaust. The presence of Judaism as a religious faith, largely because of the observant member, established a tone of respect for religion at a moment in time when feminists of different faiths often viewed religion solely as patriarchal and oppressive. Other BWHBC founders were influenced by the social justice concerns of a more secular Judaism. Both cultural and religious Judaism formed the background to the group’s Jewish influences.

Because of the longevity of the BWHBC, it became central to its members’ lives in an unusual way. Several members described the collective as an extended family that shared leisure time, holidays (especially Passover seders), and life-cycle events as well as professional and political work.22 The close integration of members’ daily lives and social concerns created a spirited community environment as well as a safe space for topics related to personal identity and growth. Though not a part of the collective’s project, Jewishness was important to individual members, and issues regarding anti-Semitism were frankly discussed when they emerged. But it took several years for the fact of the group’s large number of Jewish members to surface. Various members recall the “eureka” moment at a meeting in the early 1970s when together they realized that more than three-quarters of the group were Jewish.

The connection to parenting is another factor related to the collective’s Jewish identity. Issues of female health, sexuality, childbirth, and reproduction were at the forefront of the collective’s concerns, but because of the women’s own experiences as mothers, support of parenting became a goal as well. In contrast, most members of the initial women’s liberation collectives were younger and single. Bread and Roses, for example, included day care and other parental supports in its laundry list of issues, but these concerns were not central.

The BWHBC formed a parenting study group, which created a second book, Ourselves and Our Children, published by Random House in 1978. The book disseminated the notion that good parenting was vital to feminism, women, children’s well-being, and society at large. Even after the parenting group dissolved, the issue remained among the spectrum of BHBCW concerns. Some members connected this focus to the influence of the family values by which they had been raised.

Members point with pride to the fact that the BWHBC became a multigenerational community, with three and even four generations of families involved in Passover seders and other celebrations. Children, parents, and sometimes grandparents and grandchildren, as well as friends of family members, became part of the amplified Our Body, Ourselves group. This intergenerational community spoke to the women’s ongoing commitment to each other and to their families’ well-being, extending beyond casual get-togethers to lifelong support. The seders also expanded to include significant others, children, close friends, and colleagues, until it became a large communal gathering for an important segment of the women’s health movement in Greater Boston.23

The family aspect of the collective helps us to understand the ways in which the whiteness of the organization’s first decades was also a product of its Jewishness. In the preface to the 1973 Our Bodies, Ourselves, the founders identified themselves as “middle class . . . [with] at least some college education, . . . some [with] professional degrees,” and although they did not specify race, they were definitively white as well.24 The fact of Jewish identity, unmarked by outsiders and, at least for several years, unacknowledged even by the founders themselves, created additional familiarity that enhanced group solidarity.

Yet the close ties between founders created unintended problems. In scholar Kathy Davis’s view, the collective’s “mythical narrative,” composed of “origin story, heroic tale, and family saga,” unwittingly prevented newcomers from joining the group on equal terms.25 Davis contends that because of the founders’ failure to confront the differences that separated them from newer staff, they ignored the “institutionalized, heterosexist, and racialized” power structures that operated even within feminist organizations. Conflicts between women of color and white women founders played out as racial issues. Davis notes that similar problems plagued other feminist groups originated by largely white, middle-class women, who, in spite of attempts to diversify, inhabited layers of privilege difficult for latecomers to penetrate.26

BWHBC founders attempted to mitigate power differentials in varied ways. Starting with the earliest editions of the book, they gave drafts of chapters in progress to readers from different backgrounds, seeking feedback regarding exclusions or insensitivities. They had multiple relationships with women of color who were working colleagues across the U.S. and abroad. Collective members also participated in a variety of antiracist workshops.

But while the founders hired women of color to perform many of the paid staff tasks since founders had jobs, careers, or family interests in between book productions, they did not invite new staff members into the group’s inner circle of personal intimacy and confidentiality or make them co-authors of Our Bodies, Ourselves or members of the BWHBC. According to founder Norma Swenson, the gap between the founders’ shared experiences and newcomers’ sensibilities was not easily bridged. “We genuinely wanted to diversify our working teams in the office, [but] they inevitably felt excluded, because in fact they were, by virtue of their social class backgrounds as well as their races. The totality of the social distance between most of them and most of us was very wide, even if we did have progressive politics . . . and even if the everyday atmosphere was always cordial and collegial.”27

Founders acknowledged that the problem was one of structural racism. “Like many groups initially formed by white women,” Jane Pincus admitted, the group had to struggle against the “internalized presumption that middle-class white women are representative of all women and thus have the right to define women’s health issues and set priorities.”28

The collective continually expanded the book’s content coverage to include more representative voices and added women of color to the board and advisory groups as well as staff. By the 1990s, the organization was no longer a collective with its original ethos of voluntarism but a group of founders with paid staff. Nevertheless tensions between the founders and some newer staff led the staff to unionize, and in 1997, several black and Latina staff members brought a discrimination complaint against the collective, which was dismissed by the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination in 2003.29 The conflict led the BWHBC to become a more formal organization with a more empowered staff and a community board of directors, with less direct involvement of most original founders.30 To mark the difference between the original structure and the new one and to reconcile the group’s name with that of its famous product, the community board changed the group’s working title from the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective to Our Bodies Ourselves (OBOS).

Outside the U.S., the collective held its central authority loosely, deferring to the experience of local translators and adapters.31 OBOS’s efforts promoted grassroots health activism throughout the United States, Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Europe. By developing innovative ways for global “translators” to adapt the book to local needs and experiences and expanding input from diverse readers and staff for the domestic volumes, the collective transformed the racial homogeneity of the original founders’ group into a more broadly based co-authorship.32 By the book’s eighth edition in 2005, the organization enlisted Latina medical anthropologist Zobeida Bonilla to serve as “tone and voice editor,” assuring that more heterogeneous voices were represented in the volume.

Other significant differences also emerged among the founders group and between founders and readers, especially during the BWHBC’s early years. At one point in the mid-1970s, questions involving the parenting subgroup threatened group harmony. The selection of the chapter title on lesbianism caused division. The resolution of these issues required intense discussions about the development of materials, the role of readers, and the inclusion of diverse perspectives.33 How to nurture more collaborative modes of knowledge gathering and dissemination remained a challenge, but the founders’ commitment to each other and their mission-driven work, as well as to working out differences, solidified relationships.

The narratives presented in this chapter complicate the issue of diversity within the OBOS by pointing to the impact of experiences with race, ethnicity, sexuality, and parenting that stem from Jewish backgrounds. There was no uniformity in the founders’ Jewish experience. Esther Rome was a practicing, observant Jew throughout her life. Paula Doress-Worters and Vilunya Diskin were influenced by religious factors in childhood, although they identified more secularly in adulthood. Nancy Miriam Hawley, a red-diaper baby who turned to the study of kabbalah in the 1970s, came to meld secular and spiritual values over the course of her life. Joan Ditzion and Jane Pincus remained secular, although elements of their Jewish backgrounds informed their work as well. Rather than being based on ethnoreligious sameness, the bonds created by Jewish background developed from respecting Jewish and other differences among collective members. There was no common repertoire of Jewishness to draw on, as there were shared female experiences.

Nonetheless, for all the Jewish women I interviewed, Jewish background was important as a motivator for personal activism. Being Jewish fostered attitudes that heightened social responsibility. It helped shape political values, bringing the women to the social movements of the 1960s and the women’s health and parenting movements that emerged at the end of the decade. Despite the diversity of Jewish pathways, Jewish heritage cemented community among the founders group, including the non-Jewish founders, providing a basis for heterogeneity and innovation. The outsider perspective of Jewish life and its characteristic mode of questioning also predisposed collective members to think differently and creatively.

Taken together, the Jewish-themed stories of the OBOS create a kaleidoscopic portrait of Jewishness and feminist health activism in the late twentieth century. While Jewishness was not a precipitating factor in the mix of circumstances that led the founders to create the initial collective, it did matter a great deal.

Esther Rome, Paula Doress-Worters, Vilunya Diskin: Spiritual Progressives

Esther Rome, Paula Doress-Worters, and Vilunya Diskin shared a deep commitment to empowering women as actors in their own lives through the power of knowledge. Rome was an observant Jew all her life. Doress-Worters attended an Orthodox Hebrew day school in a working-class community in Massachusetts, and Diskin, a child survivor of the Holocaust, was exposed to Orthodox religion in early childhood. Doress-Worters and Diskin identified social activism with secular imperatives stemming from the civil rights and women’s movements.

***

Esther Rome was a key figure in the work of OBOS before her death from breast cancer in 1995. Rome co-authored all editions of Our Bodies, Ourselves and served on the board and staff of the collective. Focusing on such topics as menstruation, food, nutrition, sexually transmitted diseases, breast implants, and body and self-image, she had a comfort with her own body that assured that she took a leading role in the group’s innovative explorations of sexuality and reproduction.34

In turn, the collective changed Rome’s life. When she went to the Emmanuel College conference and then participated in giving the “Women’s Health” informal course at MIT, she was a young married woman, with a B.A. from Brandeis, where she majored in art, and a master’s in teaching from Harvard. She taught art for one year in an intermediate school in the suburbs but found it to be a trying experience. She had no idea that her life would take a completely different turn after the fall of 1969.

The youngest of four, Esther Seidman Rome was born in 1945 and grew up in Plainfield, Connecticut, a small town where hers was the only Jewish family.35 Aided by the Jewish Agricultural Society, which relocated eastern European Jewish immigrants to rural areas in the Northeast, Esther’s paternal grandfather, who had emigrated from the Ukraine, settled his family in Plainfield, where he became a shopkeeper. His son, Leo, met his wife, Rose, at the dedication of the one-room shul that their fathers had started in a nearby village. Esther’s maternal grandparents had emigrated from eastern Europe and also became farmers. Esther’s brother, Aaron, remembers their grandmother Bessie Seidman telling the children a story about the Cossacks who slashed every feather bed in town because they believed that Jews hid their money there. Esther was close to this grandmother and brought her children to hear these same stories after her grandmother retired from her business and moved to Florida and later western Massachusetts.

Esther’s father was a devout Jew who taught himself many of the Hebrew prayers. He davened (prayed) three times a day and, with his wife, kept a strictly kosher home. Shabbat dinners every Friday night included Torah readings, with all the children taking turns reading and discussing the portions. The family was ideologically Orthodox, if not Orthodox in practice, because Leo Seidman kept his variety store open on Saturday. The children were tutored by Orthodox teachers and later studied at a Hebrew school in the nearest city. The Seidman family was gender neutral with regard to Jewish observance as it was in other respects; Esther’s mother taught her sons as well as daughters domestic skills such as embroidery and baking.

Because Esther was Jewishly isolated growing up, she chose Brandeis University for her undergraduate work so that she could be with other Jewish students. During college, she met Nathan Rome, and they married in 1967, a year after graduation. Rome came from a learned European Zionist family. In the 1930s, his grandfather Salman Schocken started a publishing company in Berlin that moved first to Palestine and then to New York after the Nazis shut it down. Schocken Books made its place in literary history by publishing the works of such Jewish authors as Martin Buber, Franz Kafka, Franz Rosensweig, and S. Y. Agnon. Esther’s relationship with her mother-in-law, Chavah Rome, the wife of artist Theodore Herzl Rome, lent a new dimension to her Jewish identity. She learned to bake Chavah’s special challah.

When Esther Rome saw a notice for the women’s liberation conference at Emmanuel College in June 1969, she was new to political movements, a young wife with a degree in art but no clear direction in her life. She quickly found meaning in the explorations conducted by the free-flowing group that formed to study women’s bodies and the foibles of the medical system. Wendy Sanford recalled, “We met every week for over a decade and every month after that in a circle of personal sharing and political work which transformed each of us. For Esther, there was a sense of coming out of a childhood of relative isolation into a circle of women that gradually moved into the heart of our lives. After a month or so, Esther said, looking around at us, ‘This group is the best thing that ever happened to me.’”36 Self-educated in the female body and its anatomy, and with artistic skills, Rome played the major role in preparing the book’s anatomy chapter and supervising graphic artists. More than that, “it was her vision,” said Paula Doress-Worters, that Our Bodies, Ourselves should offer a view of women’s bodies from their own perspective, “viewing the outside first, and then moving inward.”37

Rome was a “supremely practical feminist,” added Sanford. “She started from the experience of her own body and sexuality, and developed original, commonsense strategies to improve health.” Her answer to the problem of women being raised to be ignorant and ashamed of their bodies was “to have a look.” She “matter-of-factly demonstrated a cervical examination to us, and her demonstration was photographed for an early edition of the book.” Rome was as creative as she was pragmatic. When the others first met her, Sanford recalled, she was completing a pair of camping pants “with a zipper that ran all the way from front to back, so that a woman could pee freely in the woods.”38 Her husband, Nathan, called the pants “liberators.”39

Rome’s imagination made her especially important to the collective, as did her willingness to take on difficult issues and confront powerful medical and corporate interests. For the collective’s traveling exhibit, she embroidered anatomically correct vulva and pubic hair on a Raggedy Ann doll and gave the doll a mirror and flashlight. She developed critiques of agribusiness and the beauty and cosmetics industry and sought to combat anorexia and bulimia. To provide an alternative to useless inserts in tampon packages, she developed a red-ink menstruation brochure. Arguing for stricter guidelines on tampon labeling to prevent toxic shock syndrome, she served as consumer representative on the American Society for Testing and Materials’ Tampons Task Force. In the 1990s, she joined a working group at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to foster better research and information on toxic shock syndrome. At the time of her death, Rome had just completed a co-authored book, Sacrificing Ourselves for Love: Why Women Compromise Health and Self-Esteem, and How to Stop, about the health risks in women’s lives, including sexually transmitted diseases, domestic violence, rape, body image, and breast implants.40 Rome’s gift to the collective, said Sanford, was a “politics free of ideology . . . thoroughly embodied in the practical.”41

But while Rome’s work as a health advocate was progressive in every way, in her life outside this realm, she was a supremely traditional woman. OBOS was an “extended family,” her older son, Judah, remarks, enjoying many events together and looking out for each other, yet for the most part, Rome separated her work life from her family life. “When she was home, she was just my mother, committed to being Jewish and to having a Jewish house,” he recalled. “We kept kosher at home. We always had Shabbat. Every Friday night, we lit candles, and we had dinner together as a family. We didn’t go out, even in high school. If there was a party or something, it didn’t matter.”42 His mother was always excited for the Jewish holidays, loving the traditional meals and cooking that went along with them, and she was passionate about the rituals, fasting on Yom Kippur, changing all the dishes for Passover, boiling all the glass bowls. Scrubbing the countertop on Passover was not good enough, her husband, Nathan, remembers; she demanded that he make a separate piece of plastic laminate to cover it.43 When Rome was very ill, with only a few months to live, she was simultaneously concerned with completing her book, preparing her house for Passover, and planting her garden for the next year. When a friend asked if she could help clean Rome’s house, Rome told her to use a toothpick to make sure there was no chametz (leavened foods) lurking in the cooktops. “This was a quality of commitment that marked every aspect of her life,” said Doress-Worters. “She would have made a wonderful old woman. . . . She knew the lore that for many of us was lost with our mothers and grandmothers. She knew everything about plants. She knew traditional women’s crafts, and laws and rituals of the Jewish people.”44

For Judah and his brother, Micah, being Jewish was “just part of everyday life,” how Rome structured and ran the family. But they were equally comfortable with their mother’s public profile as a women’s health advocate dealing with cutting-edge topics regarding sexuality and reproductive rights. “I knew the word ‘vagina’” by the first grade, said Judah. “Doesn’t everyone?” While it might seem contradictory to “take on the very traditional role of making chicken soup and cleaning the house for Passover and, at the next minute, be testifying for the FDA on tampon absorbency,” Judah remarked, “they were just both parts of her identity.”45 There was no conflict. “Esther asked me once did I think her old-fashioned,” remembered Doress-Worters. “I did not.”46

Because of Rome’s strong family values and her Judaism, Judah does not believe his mother should be called a “radical.” She was not a militant, Sanford agreed; the Romes were “solidly married, deeply religious, really safe.”47 But neither was she a strict traditionalist. Esther Rome’s open engagement with sexuality was not typical of observant Jewish feminists, for whom modesty remained a Jewish commandment. Her brand of Judaism was less Orthodox or Conservative than individualistic and self-defined. Observing the Sabbath, she would not attend OBOS events on Friday nights or Saturdays. She did not attend seders hosted by other collective members if they were not kosher for Passover. In order to participate in an OBOS retreat that had to be held during Passover, Rome brought all the food.

Rome’s ardent dedication to her work and colleagues, her family, and her Judaism was to her a practical means of engaging fully in the world. Her determination may have stemmed from the fact that as a minority in the non-Jewish community in which she was raised, she had to defend her principles and lifestyle, acknowledging her difference from others in positive ways. Religion and reason, work and family, became continuums rather than irreconcilable dualities. This hybridity drew on the comfort she derived from core religious beliefs and the feminist commitment she brought to her work with the collective. OBOS founders cite Rome’s Judaism as a primary reason for the group’s acknowledgment of ethnic and religious identities.

***

At the NYU “Women’s Liberation and Jewish Identity” conference, Paula Doress-Worters remarked that her background was also unusual, because most members of OBOS came from secular and/or socialist backgrounds, and she came from a religiously observant one. Doress-Worters moved away from traditional observance, “feeling more inspired by the spirit rather than the letter of the Jewish law.”48 Doress-Worters rejected the confining elements of the Orthodox Judaism in which she was raised but became active in Reconstructionist Judaism later in her life. She acknowledges that early religious teachings had an impact on her lifelong commitment to social justice.

Doress-Worters attended the first workshop of “Women and Control of Our Bodies” at Emmanuel College in 1969 and was involved in research leading to the first OBOS courses and Our Bodies, Ourselves editions through 1998. Her major contributions included writings on postpartum women in relationships with men, and women growing older. She co-authored Ourselves Growing Older (1986) and The New Ourselves Growing Older: Women Aging with Knowledge and Power (1994) with Diana Laskin Siegal and was a co-author of the 1978 Ourselves and Our Children. In the 1980s, she co-authored with Wendy Sanford a series of articles opposing the radical Right’s attempt to censor Our Bodies, Ourselves.

Paula Brown Doress-Worters grew up in working-class Roxbury, Massachusetts, where “at least 85 percent of the neighborhood” seemed Jewish. Her parents, immigrants from Poland, came to the U.S. separately in the 1920s and met in the West End of Boston, an area of first settlement for many immigrant Jews. Shortly after Paula’s birth in 1938 and a few months after Kristallnacht, her mother’s sister and her husband fled Austria; they lived with Paula’s family in their Boston apartment for twenty years and became role models for Paula and her brother. Paula learned Yiddish as well as English as a toddler. Her uncle, who told stories about being among the first groups of Jewish men to be rounded up in Vienna, was an inspiration to Paula, a hero who used just the right mixture of “nerve, chutzpah, and quick thinking” to enable his freedom.49 Several cousins who had been in refugee camps after the war stayed with the family for shorter periods. Doress-Worters observed, “growing up with personified models of refugees from the Holocaust and the language of the people, my ancestral people, was a very powerful effect on my Jewish identity.” The loss of family members in the Holocaust motivated her to be socially active and taught her also that “silence was acquiescence.”50

The family’s religious observance was quite traditional. Doress-Worters’s devout father prayed with tefillin every morning and, despite his lack of formal training, often led weekday evening services at shul; her mother was well educated in Hebrew and knew and taught the daily prayers to her children. Doress-Worters’s father worked in a grocery store, then in a war defense plant; her mother had her own children’s clothing store. Along with many other Jews who left Roxbury, the family moved to a better neighborhood in Dorchester, but the children’s store closed because its customer base moved. Doress-Worters’s mother returned to the factory work of her earlier years. Her father was affected by the decline of mom-and-pop stores but eventually found work in another grocery store.

From the second through seventh grades, Doress-Worters’s parents sent her and her brother to Maimonides, an Orthodox day school in Roxbury started by the charismatic Rabbi Joseph Soloveichik. Doress-Worters received a firm grounding in Jewish learning there but often felt like a “fifth wheel,” taunted by classmates, whom she called the “religion police,” for such offenses as her mother’s keeping her store open on the Sabbath. She convinced her parents to let her return to public school for junior high. Jewish identity remained important to her, and Doress-Worters fondly recalls her parents’ Passover seders and Rosh Hashanah gatherings with Jewish teens around the community wall at Dorchester’s Franklin Field.

Doress-Worters was conscious of the changing face of her neighborhood, which became more African American and lower income. On her way to high school, she would see “the black kids getting on the public bus” that she took. “The conductors didn’t treat them as nicely as the white students. They would yell at them or be critical of them.” It made Doress-Worters think of the Holocaust and “the way Jews were at first, just isolated and humiliated”: “By the time I got to college,” she recalled, “I was really convinced that race was the big central problem in our society.”51 This belief created empathy for outsider groups and helped propel her activism.

Without funds to attend a four-year college, Doress-Worters completed a two-year business program at Bentley School of Accounting. After two years of office work with some night classes, she transferred to Suffolk University, a commuter school with a diverse student body primarily of white ethnics from Boston neighborhoods and western Massachusetts. After college, she worked for a peace group, then was a community organizer in Dorchester. While other college graduates were going south to participate in civil rights actions, Doress-Worters thought that “as someone who grew up in Roxbury and Dorchester and saw the neighborhood change,” she could make a contribution locally. She became the sole staff member at the Washington Street Action Center, immersing herself in the community’s culture and hoping to contribute to the welfare rights movement. The program was initiated by ERAP (the Economic Research and Action Project), an offshoot of SDS.

Doress-Worters married Irv Doress, a sociologist, and after the birth of their first child, moved to Arlington, where they both worked on fair-housing campaigns and other civil rights projects. Doress-Worters also joined a woman’s consciousness-raising group. When a young woman remarked to her that she had gone to Boston “to be in the women’s movement,” Doress-Worters realized that Boston was developing a national reputation as a center of the growing movement.52

Doress-Worters pointed out one difference between Boston’s two women’s liberation groups at the time. Cell 16, also known as Female Liberation, was the first women’s group in the city. Drawing on young women in their early to midtwenties, it focused on consciousness-raising, self-defense, and advocacy of separatism from men. Bread and Roses attracted a slightly older group, young women in their mid- to late twenties and a few, like Doress-Worters, in their early thirties. Most were socialist feminists, closely aligned with the New Left.

But there was another difference. One former Female Liberation member told Doress-Worters that while her group attracted non-Jews, the Jews went to Bread and Roses.53 Doress-Worters agreed and added, “the majority of women in the [OBOS] group were Jewish, but we weren’t talking about being Jewish because we were much more focused on gender equality and learning about our bodies.” Yet she was aware of the Jewish members of her various women’s groups: the consciousness-raising group, which was more diverse; Bread and Roses; and the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. In Bread and Roses, she was “drawn to Jewish women from New York who just were so out there about being Jewish. Not that they were talking about being Jewish but they weren’t self-conscious about being perceived as too aggressive or too loud.” To Doress-Worters, these Jewish women demonstrated a confidence and pride different from the attitudes of Jewish women such as herself who had grown up in Irish- and WASP-dominated Boston. Given their political backgrounds, they seemed “entitled to have a platform to somehow effect social change. And they just seemed very capable and strong and just very good role models.”54 Rather than the negative connotations of Jewish women’s assertiveness internalized by others, for Doress-Worters, Jewish women’s stereotypical traits reflected more positive characteristics. And as opposed to many Jewish women in women’s liberation groups who declared that they had been unaware of members’ religious/ethnic backgrounds, Doress-Worters was well aware of Jewish women’s voices and presence. Boston is a very ethnically conscience city, she noted, and at college, she was often asked, “What are you?”—meaning what ethnic group: “as if that were the core of our being.”55

After three decades, Doress-Worters retired from women’s health work and came to the Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis University to explore the legacy of suffragist Ernestine Rose, a nineteenth-century pioneer women’s rights advocate neglected by historians, perhaps because of her identities “as an immigrant, an atheist, and a Jew.”56 Doress-Worters has published a two-volume collection of Rose’s speeches and letters and established an Ernestine Rose Cemetery Society to restore Rose’s burial site. In 2012, she traveled to Poland with her daughter to present a paper on Rose at the twentieth anniversary of the Women’s Studies Program at Lodz and to visit the city of Rose’s birth in nearby Piotrków and her parents’ birthplaces in the Ukraine.

Like Ernestine Rose, Doress-Worters sees herself as a committed feminist social activist but also as a “radical Jew.” “In the civil rights and feminist movements, we identified as universalists,” Doress-Worters noted.”57 Yet although OBOS never explicitly recognized the influence of Jewish social justice values, she believes that it enabled members to act in the tradition that she calls radical Jewishness. “While we may have universal aspirations in terms of wanting to come up with interventions [and] social actions that will benefit society as a whole, we come to these goals with our own individual particularities,” Doress-Worters said.58 As for many other women’s liberationists, Jewish particularity, reflected in the ethical values and political actions of Jewish culture, was the other side of universality.

***

As a child survivor of the Holocaust, Vilunya Diskin has a unique profile within the collective. Exposed to Jewish observance early in her life, she strayed from it in later childhood and her adult years, rekindling her spiritual connections decades later. At OBOS, Diskin (known as Wilma until she changed her name) focused on international women’s issues. She has traveled extensively to promote women’s health abroad, particularly in Mexico and India.59 Diskin also created and managed Vilunya FolkArt, a shop and gallery of indigenous art, and is involved with various textile projects.

Diskin was born in the small town of Przemyślany, Poland, in 1942. Her family had been prosperous; her grandfather owned a textile mill, her mother was a lawyer, and her father was a chemist. With the exception of Vilunya, her entire family perished at the hands of the Nazis. In addition to an older brother, she had a twin sister who died either at birth or as an infant; she does not know the details. Diskin was saved because her parents made arrangements with their Catholic maid to hide her in her village. After the Soviets liberated the town of Lvov two years later, the woman brought Diskin to Rabbi Israel Leiter, and his wife, Esther. The Leiters joined the partisans, attempting to save Jewish children. They took Diskin into their home, where she lived as the Leiters’ daughter for a few years; they had lost one of their daughters during the war.

The Leiters were warned that the authorities were about to arrest them and fled Lvov. Diskin remembers their escape to Czechoslovakia and then to Hamburg, Germany, where they spent two years waiting for a boat to America. In 1948, they finally arrived in New York. Her memories of that time focus on the family’s Shabbat dinners, which included other refugees, with prayers, candles, food, a beautiful table, and the singing of zmirot (Jewish hymns) after dinner. “I felt the joy and longing in their singing,” she recalled. “I was a witness to a profound example of survivors integrating their excruciating losses, as these wounded people, who had lived the imaginable, found the capacity to create a haven of warmth, love, and safety for their children. I felt cherished and enveloped in that love. It formed the emotional core of Judaism for me.”60

Following the policy of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society to place refugee orphans with American families, a Jewish family in Los Angeles adopted Diskin. She described them as conventional, middle-class liberals who felt terrible about the Holocaust and “wanted to help the kids.” She enjoyed a normal, happy childhood with them, but in retrospect, she realized that she experienced a “cultural chasm” in moving from a European, Orthodox household to an American, Conservative one. In the Leiters’ home, “God was the life force”: “All our actions, thoughts, and desires were focused on obeying biblical rules and regulations because this was the ethical code for living a worthwhile life.” At her adoptive family’s home, “God was a once-a-week and holiday presence.” Friday nights were different: “there was no joyous singing, no lingering over prayers, no emotional attachment to God.” Religion was now “a series of rituals to perform” rather than a “joyous emotional” experience.61

Although Diskin went to services with her family and for some years attended Jewish summer camp, if she identified as Jewish, it was only “lightly so.” Being Jewish did not “figure much in [her] consciousness.” Authentic Judaism meant the Leiters’ religious enthusiasm, not the secular liberalism of Los Angeles Jews. Nonetheless, Diskin was able to develop a sense of moral purpose that fit her assimilated upbringing. Fundamental Jewish values led her first to the civil rights and antiwar movements and then to women’s liberation and the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. As Diskin explained, “I began to transfer my visceral feelings of connection to God to a cultural identification with Judaism, which later morphed into activism and politics. I began to feel that being Jewish didn’t necessarily mean a belief in God, but it did mean living according to the prescribed code of Jewish ethics. Being Jewish meant making a commitment to recognize discrimination, and prejudice, to fight against it, and to be vigilant in fighting against another Holocaust. In the American context, this meant organization and advocating for equal rights and opportunities for all.”62

As a student at the University of California at Berkeley and then UCLA, from which Diskin graduated in 1963, she became active in the civil rights movement: “as did every other Jewish person in my crowd.” She “identified with Blacks and felt that [the two groups] shared a common history because Jews had been slaves in Egypt. Blacks were treated as less than human in the American South: Jews had been treated with suspicion and prejudice throughout Europe culminating in the Holocaust. Standing in solidarity with the civil rights movement felt familiar, the right place to be.” Participation in civil rights was integral to Jewish values and to Jewish peoplehood. “It never surprised me when Jewish people were at the forefront of social justice.”63

Diskin shared her passion for social justice with Martin Diskin, the son of Russian-immigrant Jews, whom she described as a “progressive, intellectual, culturally identified but non-practicing Jew.” Both studied the anthropology of Latin American societies, moving to Mexico shortly after their marriage to do field research. All their friends were non-Jewish Mexicans. Working with indigenous peoples, their Judaism never surfaced. “We never even celebrated the Jewish holidays.” Back in the U.S., where Martin had taken a position on the anthropology faculty at MIT and Vilunya gave birth to her first child, she tried to re-create the “warm Jewish presence” she had imprinted from childhood but still felt great loss.64

In Cambridge, Diskin’s friend Jane Pincus, whom she knew from a childbirth class, told her, “We’re going to a women’s liberation meeting.” Diskin asked, “Liberation? From what?” The two women joined a consciousness-raising group that became one of Bread and Roses’ first collectives and were core members of the group that formed OBOS. The collective shaped the course of Diskin’s work life and contributed to her personal growth over many decades.

“We got to be such good friends,” Diskin remarked. “We got to be family. We worked together. And our families became friends.” They went to each other’s parties, weddings, bar and bat mitzvahs, seders. Because of this familiarity and because Jewishness had played such a meaningful role in several of the women’s lives, “being Jewish was very comfortable in the group.” Collective members discussed their own Jewish identities when relevant, but they did not dwell on them. When difficult subjects such as the Holocaust and anti-Semitism arose, these issues were discussed openly. Diskin remembers a non-Jewish member describing how she felt when her family made anti-Semitic remarks and, on another occasion, the woman responding to Diskin’s diatribe against “terrible atrocities committed in the name of Jesus” by reminding Diskin that “Jesus was a good guy.” “I’m ranting about all the people in his name who don’t act like Jesus at all,” she responded. “Our Bodies, Ourselves was a safe environment where you could really discuss anything,” Diskin commented. “We had lots of heavy-duty discussions. But at the end of the day, we would get through whatever it was that we got into because of the enormous trust and love and affection [that] was there—and respect.”65

Diskin’s Jewish identity grew deeper over time. For many years, she felt that her Jewish journey had taken her down two parallel paths: the intense, emotional connection to Judaism, which she identified with the Leiters, and the secular identification developed in her American household. While she mourned the loss of the religious longing and joy she experienced with the Leiters, she rejected their God-centered theology that seemed irrational to her after the horrors of the Holocaust. Eventually Diskin understood that there were “many examples of good behavior in terrible circumstances” and that she could hold two opposing truths. The two paths now seemed interwoven, “like a khallah,” she said, rather than contradictory.66

Today she has come “full circle.” She participates in a Reconstructionist Jewish synagogue, studying Hebrew and the Bible. “When I hear the Hebrew prayers,” she said, “I feel a bond to the generations of Jews who came before me,” even though as a child of the Holocaust, she never knew her family of origin. For this reason, her bond to the Jewish collectivity may have become even stronger. And she is fully engaged in teaching her grandchildren “Jewish values: the importance of education, critical thinking, compassion for those different and poorer than ourselves and to act in the world to leave it a better place.”67 Prayer and ritual along with activism and social consciousness have emerged as joint touchstones of her Jewish identity.

The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective and Diskin’s Judaism have served as the two parallel paths of her life. The critical thinking and social action that Our Bodies, Ourselves generated, leading to concrete improvements in millions of women’s lives throughout the world, stand as enduring testimony to the power of goodness and the force of ethical action amid the complex and often terrifying conditions of human existence. Diskin’s participation in, first, the Jewish-inflected community of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective and, later, its multicultural, global one has been one expression of her Jewishness. At the same time, the collective affected that Jewishness through its core values and achievements. Carrying those values with her, Diskin has at last found a home in the synagogue she chose because of its commitment to gender equality, feminism, and social action. With many mixed families, it is a diverse and pluralistic Jewish community. Being a part of two special communities—the synagogue and the OBOS collective, both dedicated to the pursuit of social and ethical imperatives—Diskin considers herself fortunate. “L’dor v’dor,” she said—from generation to generation. “Let us maintain and add to the traditions we all share.”68

Nancy Miriam Hawley, Joan Ditzion, Jane Pincus: Political Radicalism and Jewish Family Values

As daughters of political radicals, Nancy Miriam Hawley and Joan Ditzion shared a red-diaper background. Their parents’ beliefs helped shape their political convictions and, together with their exposure to youth and student movements during college, brought them to the New Left and antiwar movements. Jane Pincus’s family background did not orient her to activism, but she became involved in antiwar politics and feminism.

***

Nancy Hawley co-wrote several Our Bodies, Ourselves chapters, serving on the collective’s board for many years. She has been a clinical social worker, group therapist, and organizational consultant. Like several of the collective’s founder-authors, Hawley re-created her Jewish identity over her life course. She began with a connection to Jewish traditions that led to political radicalism. Later she commenced a course of study that took her to kabbalah, Jewish renewal, mysticism, and Buddhism. As she was turning fifty in the early 1990s, she changed her name from Nancy to Miriam, a mark of the bond she felt with one of the Jewish tradition’s most iconic heroines.

Hawley came to political radicalism through the New Left and to the women’s movement through her experiences as a mother and radical. She gave birth to her first child in 1966 and, shortly after, became part of a consciousness-raising group in Cambridge, Massachusetts, most of whose members had young children. She was already a member of SDS when in the fall of 1968, she got a call from Marilyn Webb urging her to go to Lake Villa, outside Chicago, where SDS women planned a November gathering to discuss women’s issues. Unlike other attendees who were disturbed by the rancorous proceedings, Hawley came away euphoric. Having heard Shulamith Firestone pronounce pregnancy “barbaric” and call for the replacement of biological means of reproduction with artificial ones, she intuitively understood that the movement needed her pro-motherhood voice.69 She began meeting with several SDS women to consider “what it was like to be a woman within the Left.”70 From these beginnings came the Emmanuel College conference, at which Hawley offered the auspicious workshop on “women and their bodies.”

Hawley grew up in a minimalist Jewish family, the daughter of parents who had what she calls a German Jewish and Russian-Polish Jewish “mixed marriage.” Her mother was raised in the small town of Sweetwater, Tennessee, where they were the only Jewish family; her grandfather, because he looked the part, played Santa Claus at the town’s Presbyterian church. Hawley’s father was a first-generation Jew from a poor family on New York’s Lower East Side. Two stories about her paternal grandfather, a barber, became family lore. One was that he got permission from the rabbi to work on Saturday to support his six children. The second was that he trimmed Trotsky’s beard when Trotsky was in New York.

When Hawley’s mother went to New York at age thirteen, she was eager to learn Hebrew. Her devout Christian friends in the South had prayed for her salvation by Jesus Christ, and now she saw the opportunity to learn a tradition of her own. But she dropped out after being placed in a Hebrew class with six-year-olds. That was the end of her Jewish learning. She would have nothing to do with Jewish life, becoming an atheist. Hawley’s father had also moved away from Judaism, though Hawley believes that while outwardly he gave up the trappings of the tradition in which he had been raised, privately he remained a spiritual person. When he died, she said, “I decided to say Kaddish for him . . . every night, knowing that he would appreciate it, and that was a spiritual connection between us that was unspoken.”71

Later in childhood, Hawley and her family moved from the Upper West Side to suburban Westchester County, where they were among the only Jewish families. In her new community, she felt she had to keep her Jewishness hidden, though apparently her family’s ethnicity was known. On one Rosh Hashanah, when Hawley went to school, a classmate berated her for being there on a High Holiday. “I felt mortified, . . . really furious at my parents that they didn’t keep me home,” she recalled.72

Hawley was a red-diaper baby whose parents, especially her mother, were involved in the Communist Party in the 1940s and early 1950s and active in the defense of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. “Social justice was the family’s religion,” she noted. “I grew up singing songs of Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, the Weavers, and Odetta.”73 But as the child of political radicals, Hawley felt “equally hidden,” unable to speak about her family’s politics. Although she was visible by being smart and athletic, she felt “shut off” from her real identity. Hawley’s sense of alienation and her anger at her parents mirrors the experiences of many Jewish teenagers from left-wing families during the McCarthy period. Jewishness and radicalism were a difficult combination, particularly for those in communities that welcomed neither left-wing politics nor Jewish culture.

Hawley was the first person in her family to go to college. Looking for a “political home,” she aptly chose the University of Michigan and was there for the birth of SDS on its campus in fall 1960, when she entered the school. “It was very, very fulfilling,” she recalled. “I found that I could be out as a radical political person. Judaism was not an issue. That went underground completely at that point.”74 She felt a tinge of anxiety, though, when midway through college, she married Andy Hawley, a non-Jewish SDS activist who at one point had roomed with Tom Hayden, an SDS founder, but her parents and paternal grandparents readily accepted her husband and the marriage. All her mother wanted was for her to complete her degree.

In the “hot center” of radical activity at college, Hawley graduated with a degree and social and political connections. After the Lake Villa conference, she played a key role in developing and spreading ideas about an autonomous women’s movement, participating in her Cambridge consciousness-raising group and Bread and Roses, and co-organizing the Emmanuel College conference and the women’s health course that followed. Hawley also coordinated the first Women and Their Bodies newsprint publication.

“The women of the Collective are my family,” Hawley said.75 Wendy Sanford remembers the collective meeting in Hawley’s living room, as Hawley sang Hanukkah songs to members’ children. In the early 1970s, now divorced, Hawley met Jeffrey McIntyre, the son of a Methodist minister and a serious student of Buddhism; she and McIntyre married in 1978. His influence helped her to acknowledge the spiritual and religious interests that had lain dormant for years. In the early years of the women’s movement, religion was still regarded by many leftists as “the opiate of the masses,” Hawley remarked.76 But through her husband’s religion-centeredness, the influence of Esther Rome’s practices, and the bonds that the collective’s Jewish women and children shared, Hawley began a journey to rediscover her Jewish heritage. She was guided by an impressive group: Yuval, an Israeli teacher of kabbalah; Zalman Schacter-Shalomi, the charismatic leader of the new Jewish Renewal movement; and Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Zen Buddhist teacher and noted peace activist. From these teachers, Hawley created her own eclectic mix of Jewish-Buddhist practice, eventually joining B’nai Or, the Jewish Renewal movement synagogue in Boston. With Rabbi Schacter, she created a “Budda-Mitzah” (rather than bar mitzvah) for her son.

In 1991, shortly before Hawley’s forty-ninth birthday, she decided to change her given name to Miriam, admiring the leadership qualities of the biblical heroine. She created a naming ceremony for herself, with her guests sharing a mikveh (ritual bath) with her in a New Hampshire lake. She asked her parents to speak on why they had not given her a more Jewish name. “It wasn’t in the tradition then,” her mother replied.77

Hawley’s journey into Judaism continues. While sometimes she feels “like a misfit in terms of not being a religious Jew,” she is buoyed by her children’s interest in their heritage, despite the fact that their assimilated upbringing repeated her own. She helped her granddaughter create a bat mitzvah ceremony and is proud of the fact that one young grandson started to learn Yiddish. Like Diskin, Hawley noted that “the traditions go on” and that it is “totally thrilling.” With four generations now attending OBOS’s seders, Hawley remarked on the empowering aspect of reclaiming the tradition of Judaism: “the same way we had reclaimed our bodies.”78

***

Joan Ditzion, co-author of all nine editions of Our Bodies, Ourselves as well as Ourselves and Our Children and Our Bodies, Ourselves: Menopause, comes from a secular, socialist background. In addition to writing for OBOS, she helped edit the publications and was the collective’s principal art designer. Ditzion’s work with the collective inspired her to go to social work school, and she became a geriatric social worker, focusing on aging, older adults and family caregiving.

Ditzion emphasized the ways in which Jewish family values meshed with the collective’s perspective on parenting. Raising children is all-important work, she said, and parenting—if chosen—“should not be the turf of the right wing.” OBOS claimed a “feminist perspective to family values” and a parallel goal for women to control of their bodies and reproductive rights, which connected to Ditzion’s upbringing.79

Born in 1943, Ditzion grew up in a close, extended family with a strong, cultural Jewish identity. The family did not go to synagogue, but they celebrated Jewish holidays. Because of her father’s stories about his boyhood, anti-Semitism became a “palpable theme” in Ditzion’s childhood. Ditzion’s father, a first-generation American, grew up in the Bronx in an immigrant, Yiddish-speaking home and had to navigate his way through a neighborhood where gangs of young toughs made the life of a young Jewish boy (the “Yid,” as he was called) difficult. Ditzion grew up in a Protestant area of the Bronx, and as one of the few Jewish children in school to stay home on Jewish holidays, she also had to deal with difference early on. When she saw young girls wearing pretty organdy dresses for their communions at the neighborhood church, she absorbed that standard of beauty as her ideal. “It wasn’t like, ‘I’m proud to be Jewish,’” she commented, even though today she declares her pride in her Jewish identity and heritage.80

Although Ditzion’s immediate community “didn’t feel Jewish at all,” her family was the “core center” where she always felt a strong sense of her Jewishness. At her paternal grandparents’ house in the Bronx, she would watch her grandmother make Shabbat. In addition to her father’s Orthodox old-school parents, she was influenced by her maternal grandparents, born in America and much more assimilated than her father’s family. Her maternal grandmother had supported the suffrage movement and shared the work of a ready-to-wear store that she and her husband owned. This grandmother and her aunts provided Ditzion with “vital, strong” female Jewish role models. Ditzion said, “Feminism was a logical thing; it wasn’t a rebellious thing ever. It was just an outgrowth of my roots.” Nonetheless, although her brother was bar mitzvahed as a matter of course (he became a Jewish communal executive), a bat mitzvah for her was not discussed. The men in the family were “great, good men,” not really sexist, but the women “kept things going.” Ditzion was aware of women’s contributions, despite the “1950s mentality,” but it was not until the women’s movement that she adopted a “women-centered” worldview.81

The progressive, social justice values of Ditzion’s parents were crucial ingredients in the social consciousness she formed at an early age. Her father, a high school math teacher and department chair, and her mother, a guidance counselor who worked primarily with African American students, were members of the teachers’ union, linked to the Communist Party. Growing up, Ditzion was unaware of this affiliation, learning of it only in the early 1970s. When friends of theirs lost their teaching jobs because of McCarthyism, she attributed their distress to the fact that they were all members of the union. Ditzion remembers the shock of the Army-McCarthy hearings, which she watched on television with her parents when she was in the fifth grade. McCarthyism on the negative side and the struggle for civil rights on the positive were formative ingredients in what she called her “social justice upbringing.”82

Recollections of the harassment that the Ditzions’ teacher friends experienced during the McCarthy years led them to go west to support their daughter, who had to appear before Max Rafferty, the superintendent of education in Berkeley, California, and sign what they suspected was a loyalty oath in order to receive her teaching certificate. Joan had gone to the University of California at Berkeley for her master’s degree in art education after graduating from City College in 1963. She ran smack into the middle of the Free Speech Movement and was arrested at one protest, spending one day in jail—hence the parental visit, which Joan found moving, if unnecessary.

Ditzion did get her certification and returned east after a year of teaching at Berkeley High School. In 1967, she married Bruce Ditzion, then an intern at Brigham’s Hospital in Boston and later a medical resident at the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, where Joan taught art in an experimental junior high school humanities program. In January 1969, she attended the anti-Nixon inauguration protest in the nation’s capital. She has a keen memory of hearing women from Boston’s Bread and Roses speak out against male chauvinism: “We are not going to be making coffee and taking notes. We want full participation in this political process, and we want to end gender inequities.”83

The Boston women made a great impression on Ditzion, and when the couple returned to that city in the summer of 1969, she started a consciousness-raising group with a friend from Berkeley. At about that time, she saw an ad in the Old Mole, the New Left underground newspaper published in Cambridge, for a course on “know your bodies.” Ditzion enrolled and became hooked by the importance of the material and the revolutionary self-help consciousness-raising tool that the women were inventing. “It was such a breakthrough to begin to own and affirm a women’s point of view of our bodies, reproduction, and female sexuality,” she recalled. “I was excited to hear a range of firsthand accounts of childbirth experiences and learn about the pioneering work of the natural children and breastfeeding movement. My mother’s childbirth account was ‘I was in the hospital, anesthetized, and then the doctor brought you to me!’”84

With feminism in the air, the work of Our Bodies, Ourselves “just spoke to” Ditzion, she said. “It touched me at the core like no other social change movement. It was one of the most transforming moments in my life.”85 Although several OBOS founders had young children when she joined the group, she was the first to become pregnant while collaborating on the Simon and Schuster edition of the book. Ditzion stayed home with her two children, working part-time but spending much time with OBOS.

Figure 4.2. The OBOS founders gathered around Joan Ditzion, pregnant, mid-1970s. Photo by Elizabeth Cole.

At the time, not all radical activists sympathized with the desire to have and raise children. Jane Pincus recalls a banner that hung from a neighbor’s flat, “Down with the Nuclear Family,” which she felt represented a significant feeling within women’s liberation. OBOS stood for more equal gender and parenting roles as well as for empowering women’s knowledge and practice of health. It validated parenthood and gave great support to Pincus and other mothers. Reproductive rights were central to the perspective of OBOS, but within that context, “choosing parenting is a terrific option, maternity is a terrific option,” Ditzion said. To hold this view “within the context of the women’s movement” was unusual and important.86

Ditzion appreciates the compatibility of her choices with the collective’s work plan and its ideology, which she attributes in good part to her own strong family values—Jewish family values, she said. She asserted that family values must not be ceded to right-wing moralists and pointed to OBOS’s continuing support for birth control, abortion rights, and open sexual expression, as well as maternity, paternity, and parental choices. To Ditzion, the large Jewish representation in the collective contributed to this stance and created a “core bond, a Jewish bond.”87 In her view, OBOS expressed traditional Jewish family values, but in a modern, radical, way.

Jane Pincus came from a secular background like Hawley’s and Ditzion’s and was a participant in several of the social movements of the 1960s. Active in antiracist work in CORE (the Congress for Racial Equality) and the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), she protested the war in Vietnam. Pincus became involved in women’s liberation through Bread and Roses and attended the Emmanuel College workshop on women and their bodies. She was a mainstay of OBOS, writing the chapter on pregnancy for the first publication and co-editing several editions of the book with Wendy Sanford.

Born in 1937, Pincus grew up in a small town in upstate New York and then in White Plains, in a household that did not practice “anything at all.”88 Her mother wanted the children to enjoy the trappings of Christmas, so they had a tree every year. They did not observe the High Holidays, and Pincus’s only connection to a synagogue was the dancing lessons she took at a nearby Reform temple. Pincus was not aware of the Holocaust growing up or of its effect on any member of her family. Spending much of her childhood in the country, without any Jewish friends at school and no Jewish family traditions, she had no feeling for Judaism or Jewish culture. The exception was Passover, when her extended family gathered at her grandparents’ house. Her grandfather was Orthodox, though her grandmother was a spiritualist with no connection to Judaism.

Later in life, Pincus learned from her mother that her father would have loved to have been a cantor; he was a deeply religious man, according to her mother, and loved to sing. But, deeply affected by the Depression and fearful of not being able to support his family, he became a businessman. Pincus was never aware of these Jewish yearnings. She was also surprised to learn as an adult of the family’s push toward assimilation. Her father, born Pesach Katz, went to school as Percy Katz but changed his name to Paul when he was teased as “Pussy Cat.” After being “persecuted” in various ways in the 1930s for being Jewish, both he and his brother went through another name change. On Pincus’s birth certificate, her father is listed as Paul Wolfe Kates.89

Without any Jewish education or role models, Jewishness was not an important theme in Pincus’s life, but there were times when it resonated. Going to Pembroke College, the women’s affiliate of Brown University, in the 1950s was one of those experiences, since the institution segregated its dormitories by religion, housing Jews with Jews, Catholics with Catholics. Many religious discussions ensued, which Pincus approached as a pantheist. “I believed in nature,” she said. “Just a belief in the allness and wonder of things. I had no religious language or background training whatever.” Other students criticized her for not “carrying the Jewish burden.”90

At college, Jane met Ed Pincus. Coincidentally, her father had known Ed’s father, whom he called “Pinkie,” in the textile business. Ed’s family observed the High Holidays, and Ed had been bar mitzvahed; but neither Ed nor his family considered themselves religious. Ed and Jane married in 1960 and moved to Massachusetts, where Ed was a graduate student in philosophy at Harvard (he became a noted documentary filmmaker) and Jane briefly taught art in junior high school, then French at Wellesley High School. One night she watched Alain Resnais’s “immensely strong and upsetting” film Night and Fog, about the Holocaust. “I went to school the following day with my whole worldview transformed, into disbelief, deep sorrow and outrage, and that was my true initiation into learning about the Jewish past.”91

Although the Pincuses did not keep a Jewish household, observe the holidays, or provide their two children with a Jewish education, some Jewish sensibilities emerged. “I’m very Jewish in my awareness of who is Jewish and who isn’t,” Pincus said. “However unreligously we live, being Jewish is (pretty much always) somewhere in the background, popping out or more subtly coming forth at sometimes surprising times.”92

Both the Pincuses were involved in political work in the mid- and late 1960s, protesting the Vietnam War through marches, sit-ins, and draft counseling. Everybody Jane knew was resisting, many of them Jewish, but nobody thought of themselves as Jews, just activists demanding an end to the war. In 1965, pregnant with her daughter, she met Vilunya Diskin, and they became close friends. Learning about Diskin’s background as a child survivor, Pincus began reading books about the Holocaust and creating paintings in relation to what had happened. The two friends joined one of the first consciousness-raising groups in Cambridge that grew loosely out of SDS affiliations; the group met weekly for several years and became one of the Bread and Roses collectives.

With Diskin, Pincus attended the Emmanuel College conference, her newborn son at her breast. She met with the group throughout the fall, helping to plan and give the first course in November 1969 and working with others to put together the first women-centered publication on women’s bodies. This was her work group, as distinct from the personal consciousness-raising group, which soon disbanded. As OBOS founders came to know each other, their bonds deepened, and members began to share not only their work but the stories and events of their lives. Pincus thinks that the ratio of Jews to non-Jews among the founders, about three to one, created an unusual environment where Jewishness stood out and led to a consideration of Jewish aspects of social justice that may have led non-Jewish members to be “ultrasensitive” to Jewish issues, but in a positive, shared, and open way. Jewishness was simply accepted, yet it existed alongside other traditions, such as Judy Norsigian’s strong Armenian perspective and Wendy Sanford’s Quaker one. For Pincus, Esther Rome’s presence in the group as an observant, progressive Jewish feminist who seamlessly combined tradition and innovation mattered deeply.

OBOS began to have seders in the mid-1970s, when the women realized how many members were Jewish and that the non-Jewish members were interested in the Passover freedom holiday as well. One year, Ed Pincus filmed the collective’s seder, with Jane chopping nuts and apples to make charoset. Jane is talking about how much she misses Jewish traditions in her own life. Being part of OBOS enriched her with these connections to Jewishness and because of the collective’s support of parenting and family life, which Pincus, like Ditzion, associated with Jewish values.