Every gun scores a unique mark on each bullet it fires which means that they can be traced back to the original weapon

Criminals and terrorists used to believe that guns, bombs, arson attacks and even assaults using a vehicle afforded them a sense of anonymity. In recent years, however, forensic science has proven that nearly every weapon can be traced. Every gun leaves a distinctive marking on its bullets, explosive devices betray the handiwork of the bomb-maker, arsonists can be identified by their choice of accelerant and even mass-produced vehicles can be traced from a single fleck of paint. The weapons of choice may be becoming more sophisticated, but technology can tie criminals to the crime as effectively as if they had left their fingerprints at the scene.

Although it is a broad generalization, there is some truth in the belief that killers who choose a gun as their weapon do so because they unconsciously wish to demonstrate the total absence of emotional involvement that distance and the lack of physical contact affords them. But although guns are mass-manufactured, a firearm is not an impersonal or an anonymous weapon. Each weapon scores a unique series of signature markings on every bullet it fires as well as leaving gunpowder residue and other tell-tale trace evidence on the hands, face and clothes of the gunman.

However, while loading a weapon is likely to leave gun oil and microscopic traces of the soft metals used in ammunition on the gunman's hands, their presence proves only that the suspect handled a weapon. To prove that they fired it too, investigators look for soot deposits known as primer gunshot residue (P-GSR) on the trigger finger and will routinely swab both hands, the face and the suspect's clothes to establish a physical connection to the gun used in the shooting. P-GSR can be erased simply by washing the hands thoroughly with soap and water, but even the most thorough cleansing is likely to leave minute traces of its chemical components, barium, antimony and lead, which can be readily picked up using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer.

Semi-automatic pistols are the most common firearm used in gun crime today. Their self-loading mechanism means that up to 30 shots can be fired in rapid succession from a single magazine, avoiding the need for reloading. But such a sophisticated mechanism means that there are more components to put a signature on the bullet and its shell. Both the breech and the ejector mechanism mark the spent cartridge cases, while the firing pin and the rifling (a series of spiral grooves inside the barrel to increase the speed and accuracy of the bullet) score the bullet itself. Rifling grooves can be clockwise or anticlockwise and their spacing and width is arguably the single most important feature in matching the bullet to the weapon from which it was fired. But equally important are the striations made on the shell casings by imperfections in the barrel. Under a comparison microscope two bullets can be compared side by side – one optically overlapping the other – to see if there is a positive match. Then the bullet or shell can be digitally scanned into the computer and a search run to see if the same weapon was used in other unsolved crimes. Even barrels rifled in the same factory differ microscopically as the tools alter with wear.

Ballistics experts need to be familiar with many types of firearms and be comfortable with using them on a daily basis as they will need to fire rifles, revolvers, semi-automatic pistols and even machine guns into water tanks, gel boxes and targets in order to recover sample bullets for comparison. But they may also be required to assemble weapons from parts that have been recovered from a crime scene by stripping down guns stored in the firearms cache at the lab. When a malfunctioning firearm is recovered or when only one part of a suspect's gun has been found it may be necessary to try to reconstruct the weapon from spare parts so that it can be test-fired and a comparison made with bullets and spent shell casings found at a crime scene.

BALLISTIC BREAKTHROUGHS

Prior to the invention in the mid-19th century of the revolver and the rifle, both of which leave distinctive markings on their bullets, the only way to secure a conviction solely on ballistic evidence was to prove that the calibre of the bullet recovered from the victim matched the calibre of the weapon owned by the suspect. This, however, was not sufficient proof of guilt if more than one suspect owned a weapon of the same calibre. Occasionally the police were lucky enough to be able to match the paper wad used to secure the bullet in a muzzle-loading pistol with scraps of the same paper found in the killer's possession. The murder of Edward Culshaw in Lancashire, England in 1794 was solved in this manner when police recovered a fragment of a street ballad from the fatal wound and were able to match it to a torn song sheet found in a suspect's pocket, making it the earliest recorded case solved by forensic ballistics.

Every gun scores a unique mark on each bullet it fires which means that they can be traced back to the original weapon

A more sophisticated method was employed in 1835 by Bow Street Runner Henry Goddard, who unmasked a clumsy attempt by a butler to deceive his employer into believing that he had foiled an attempted burglary, presumably in the hope of receiving a reward. Instead the butler was summarily dismissed when Goddard proved that the bullet supposedly fired into the headboard of the butler's bed by the intruders had, in fact, been fired from the butler's own gun.

Goddard's suspicions had been aroused when he noticed that the jemmy marks on the butler's door and on the door frame were not aligned as they would have been if someone had tried to prise open a locked door with a crowbar. He continued his investigation and noticed the same discrepancy on the cupboard in which the 'stolen' silverware was kept. When Goddard compared the bullet lodged in the headboard with those in the butler's gun he saw that they were suspiciously similar. He then examined the mould used by the butler to cast his bullets and observed that both the 'burglar's bullet' and the butler's home-made bullet had a small dimple corresponding to a hole in the mould.

TWENTIETH-CENTURY BALLISTICS

It was not until 1912 that ballistics was officially recognized as being as powerful a weapon against crime as fingerprinting. At the Congress of Legal Medicine in Paris that year, legal expert Professor Victor Balthazard entertained his colleagues with details of a recent case on which he had been consulted by the French police.

A suspect named Houssard was being held on suspicion of shooting a man named Guillotin because his gun matched the calibre of the bullets found in the victim, but prosecutors were reluctant to proceed because the bullets had fragmented inside the body. Professor Balthazard pieced together the bullets and then compared the markings of those recovered from the corpse with one fired in the laboratory using photographic enlargements. He identified 85 distinctive characteristics including grooves or striations created by the rifling inside the barrel as well as markings made on the cartridge case by the firing pin and other parts of the gun. Houssard was convicted and Balthazard earned himself a place in forensic history as the father of ballistic science.

An Australian forensic team investigate the scene of the bomb at Bali in 2002

The most demanding aspect of a bomb scene investigation is not tracing the bombers but identifying and collecting fragments of the bomb, which will have been scattered over a large area and buried among tons of debris. Once the components have been collected and the device reassembled, it is a comparatively simple job to identify the type of explosive used and trace the individual responsible as almost every device carries the signature of the bomb-maker.

After every incident involving explosives the investigative team must follow a rigid protocol to ensure they collect every possible surviving trace of the device and avoid contamination under the most difficult conditions.

The first stage is to establish the centre of the blast and cordon off an area that can be divided into grid squares like a chess board. This enables investigators and later the legal team to pinpoint where specific items were found after the blast. An initial walk-through to collect the larger bomb fragments will be followed by a more thorough fingertip search, concentrating on those areas where shattered fragments of the device had been found on the first pass.

Then the debris is swept into the centre of each square using sterilized brushes and each pile is sifted in the search for wires, batteries, timing devices, nails, ball bearings and twisted fragments of the casing. But even the most thorough searches can sometimes overlook vital clues, especially if there is a large amount of material scattered over a very wide area, as was the case in the Lockerbie bombing of 1988 (see here).

Once the area is cleared and any structural damage to the building has been temporarily secured, forensic experts can move in to search for residual traces in the hope of identifying the type of explosive used in the attack. Often the choice of explosive will point to a possible perpetrator or at least suggest a fruitful avenue of investigation. Semtex was at one time the preferred explosive of the IRA, fertilizer has been a popular ingredient with home-grown terror groups such as the Oklahoma City bombers of 1995, while pipe bombs are the most common form of home-made bomb created by lone murderers (see 'Mail Order Murder' here).

During their search forensic explosive experts will use vapour-analyzers, which act like robot sniffer dogs, and apply chemical reagents to suspicious stains which produce a positive reaction when in contact with specified explosives in much the same way that luminol does when it comes into contact with blood.

Securing the area to prevent contamination after an explosion

In the lab the recovered debris is examined in greater detail to determine if it is part of the bomb or otherwise relevant to the investigation. If it is a significant find then it is subjected to microscopic analysis and the customary toxicology tests. Any recovered residue which appears to be latent explosive or is suspected of having been in contact with either explosive or the bombers will be dissolved in a solution of acetone and water so that it can be subjected to further tests.

Handle with care: plastic explosive Semtex is difficult to detect as it has no smell

The destructive power of fire has been used by criminals desperate to eliminate the evidence of their crimes, be they murder or insurance fraud, as well as by arsonists who often report experiencing a vicarious thrill from watching flames consume a building they have set alight.

Arsonists are notoriously difficult to trace, as the nature of fire means that most physical evidence will have been consumed by the flames. However, a celebrated Japanese detective, Asaka Fukada, was able to predict a large number of arson attacks in the 1980s simply by studying the weather reports. His theory was that there is a certain type of fire-starter who sets buildings ablaze in order to relieve breathing difficulties caused by low atmospheric pressure. The image of the rising flames evidently alleviated the sense of suffocation. Others would act out of pure maliciousness or spite, such as disgruntled employees, spurned lovers and even a vengeful schoolboy who had failed an exam. These Inspector Fukada would 'out' not by accusing them of the crime but by appealing to their ego. Catching them in an off-guard moment, he would ask them casually how long the image of the fire had remained in their minds to which they would impulsively answer with evident pride, their eyes glazing over as they recollected the scene.

Modern CSIs take a more scientific approach but often achieve equal success by examining specific features that even the most intense conflagration cannot erase.

Accidental fires invariably have one point of origin, such as a poorly wired electrical point or a spot where an inflammable substance was inadvertently set alight. In contrast, arsonists typically set a number of fires to ensure that the blaze will spread. Investigators will begin at the lowest level of the building where fire damage is evident in the knowledge that fire spreads upwards so there is less likelihood of finding an ignition point on the higher levels. Clues can be found in the smoke patterns and charring which discolour surviving walls, floors and ceilings.

To the trained eye a burnt building can be read in a similar way to a dead body – its wounds betray the manner of its destruction. Spalling (the sequence and degree of damage to structural surfaces) can lead investigators to the source of the blaze, as can the specific type of damage to the furniture and fittings.

CHECKING ALL THE EVIDENCE

Having found the primary source of the blaze there is then a choice of equipment available for identifying the accelerant, which could be anything from a home-made petrol bomb to a sophisticated explosive device set off by a timer or signal from a mobile phone. Fortunately, investigators are now armed with devices such as hydrocarbon vapour detectors which sample the surrounding air and detect the presence of a chemical accelerant which will remain even after the most intense fire.

But an experienced investigator will rarely have to rely on high-tech equipment. Inflammable liquids such as paint thinner and solvents leave pungent odours that linger in the air long after the flames have been extinguished, as well as burn patterns and stains on flooring where they pooled when ignited.

In addition to combing the immediate area for footprints, tyre tracks and signs of forced entry, the investigation team will also closely examine alarms and sprinkler systems to see if they have been disabled. Whether it is a private residence, a public building or a place of business, detectives will question the owners as a matter of routine to determine if there might be someone they suspect of having a grievance against them. Anyone suspected of having a motive for arson would be interviewed and their clothing and footwear examined for any traces of accelerant or other trace evidence to link them to the scene.

Suspect vehicles are blown up in controlled explosions, particularly when a terrorist attack is threatened

Computer-generated reconstructions are becoming a familiar feature of murder trials in the United States, but there is increasing concern that juries are accepting them as factual representations of what happened, rather than as just one possible scenario. The dangers of accepting computer-generated reconstructions as evidence was highlighted in 1991 at the trial of Californian pornographer James Mitchell.

Forty-year-old James was on trial for the murder of his younger brother Artie. There was no denying the fact that James had killed Artie, for the five shots that had left the hard-drinking, drug-taking strip-club owner lifeless in the bedroom of his San Francisco home had been caught on tape by a 911 operator.

The question was, had James planned the shooting, or was it committed in the heat of the moment? The distinction was critical as premeditated murder carried a mandatory life sentence in the state, whereas manslaughter would put him away for just five or six years. The pair were known to have had heated arguments that frequently resulted in an exchange of blows, but they had always managed to bury their differences before either had suffered a serious injury. But on the 27 February 1991 it was different and their partnership was terminated, permanently.

At 10.15pm that night police arrived at the scene to find James pacing up and down outside the house in an excitable state, brandishing a .22 rifle and sporting a .38 Smith and Wesson revolver in a shoulder holster. Once he had been disarmed they went inside, where they discovered Artie's body. He had been shot in the stomach, the right arm and in the right eye. Eight spent .22 shell casings were found nearby.

CRUCIAL DETAILS

At the trial the prosecution argued that the long space between shots, which could be clearly heard on the 911 tape, clearly demonstrated intent. Had it been a spontaneous shooting the shots would have been fired in quick succession.

Based on spectrograms of the shots, forensic acoustics expert Dr Harry Hollien was able to identify where each shot on the tape occurred. From this the prosecution were able to create a computer-generated video animation of the murder in which a figure representing Artie was shown being pursued by another – his attacker.

In court the film was accompanied by a commentary from Arizona criminalist Lucian Haag, who explained that the sequence of events had been determined by tracing the trajectory of the bullets to the impact points and reproducing any deflections in the crime lab. Haag had even gone to the trouble of buying a door like the one in the victim's house and shooting at it so that he could measure the angle of deflection under controlled conditions.

Such thoroughness impressed the jury, but the defence successfully argued that, with so many bullets, there were thousands of possible variations and that the video animation was only one scenario, albeit the most likely. The judge ruled that the video was to be treated as speculative, not definitive. It was not the job of the crime scene investigators to imagine the scene, but to present the facts and interpret the science.

Without a material witness to give evidence as to James Mitchell's state of mind at the time of the shooting and testimony as to the sequence of events that led up to the fatal shooting, the jury could not be expected to find him guilty of first-degree murder. Consequently James was acquitted on the murder charge but found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to six years in jail.

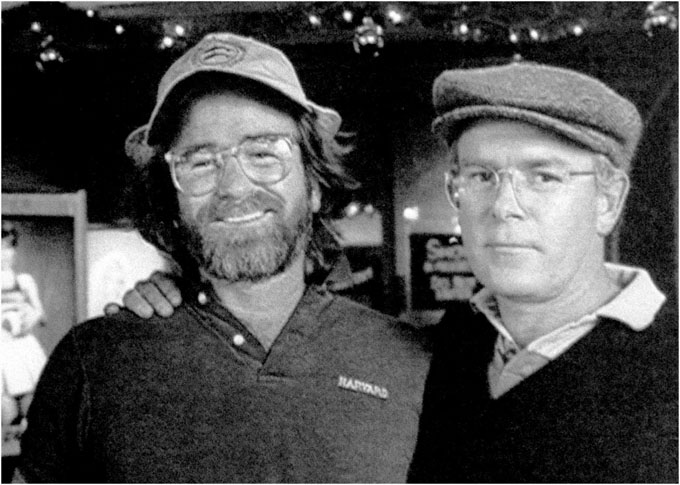

Brotherly love: James and Artie Mitchell together in happier times

Just hours after WPC Yvonne Fletcher was gunned down outside the Libyan Embassy in St James's Square, London on 17 April 1984, wild rumours were circulating in the media that threatened to ignite an already volatile situation in the Middle East. Some were of the opinion that she had been deliberately targeted by Israeli agents stationed on the roof of the embassy in an effort to spark a war between Britain and Libya which might have served Israel's interests. Others blamed militants among the anti-Gaddafi faction who had been protesting in front of the embassy when the shooting took place. It was therefore a matter of great urgency to discover the true identity of the gunmen if a potential conflict in the Middle East was to be avoided and the killers brought to justice.

Britain's leading forensic pathologist, Dr Iain West, performed a postmortem on WPC Fletcher within hours of the shooting, during which he was surprised to discover that one single 9mm sub-machine-gun bullet had passed through her body, creating four distinct wounds in her back, abdomen and left arm. Suspecting that these entry and exit wounds were to be crucial in determining the trajectory of the fatal bullet and the location of the gunman, Dr West had them photographed. He then travelled to the scene while the siege was still in progress and stood where WPC Fletcher had stood, seemingly oblivious to the danger still posed by the gunmen inside the building. There were several witnesses among the protestors, police and bystanders who were willing to testify that they saw two gunmen firing from the first-floor window of the embassy, but the situation was so politically sensitive that the police needed irrefutable forensic evidence to corroborate their statements.

From the post-mortem photographs, Dr West was certain of the angle at which the bullet entered the victim's body and he knew from TV footage of the incident exactly where WPC Fletcher had been standing. She had had her back to the building and her arms were folded across her chest, which accounted for the multiple wounds as the bullet entered her back, exited her abdomen and perforated her elbow.

Police attend to WPC Yvonne Fletcher moments after she was shot

Back at the laboratory, Dr West used an inclinometer to calculate a maximum angle and concluded that the bullet could not have come from the roof or from street level but must have come from the first or second floor of the Libyan Embassy.

THE EVIDENCE IS CLEAR

Despite this compelling evidence, the perpetrator was never brought before a British court to answer to the murder of WPC Fletcher. Desperate to resolve the stalemate in central London, Britain broke off diplomatic relations with Libya and expelled all of its diplomats, which meant that all 30 inhabitants of the embassy walked free from the besieged building, despite the fact that only 22 had full diplomatic status.

In the wake of the siege the police found discharge residues and other incriminating evidence of gunfire having come from a first-floor window, as well as a cache of arms and ammunition including a weapon that had been used to assassinate a Libyan journalist in Regent's Park four years earlier.

At the inquest Dr West testified that WPC Fletcher had been so severely wounded that no one could have saved her. The bullet had entered her back at a 60-degree angle, passed through her liver, crashed into her spine, sliced through the pancreas, re-entered the liver and ruptured the main vein in her abdomen. There were nine other victims at the scene treated for gunshot wounds, all of whom recovered.

Today a plaque marks the spot where WPC Fletcher died and residents ensure that there are always fresh flowers beside it.

Armed police move in to surround the besieged Libyan Embassy

Detectives usually have difficulty persuading the guilty to confess to their crimes, but in the case of the murder of 17-year-old Rosemary Anderson they had two conflicting confessions from two different suspects to choose from! How could they be sure they had charged the guilty man? It took 40 years and the use of a new forensic science to uncover the truth behind a serious miscarriage of justice and reveal the true identity of a hit-and-run killer.

On the evening of 9 February 1963, John Button invited his girlfriend, Rosemary Anderson, to his parents' house in Perth, South Australia, to celebrate his 19th birthday. During the evening they quarrelled and Rosemary stormed out, determined to walk home alone. John followed her in his car, a French Simca, talking to her as she walked along the dark, otherwise deserted roadside. But she was in a foul temper and refused his offer of a lift home, so he stopped and watched dejectedly as she disappeared round the next corner. Anxious not to leave her in this mood he decided to catch up with her, but when he did so he made a shocking discovery. Rosemary was lying face down at the side of the road, bruised and bleeding, the victim of a hit-and-run driver. In desperation John carried her limp body into his car and rushed to the hospital, but there was little the doctors could do. Rosemary died shortly after being admitted and John was charged with manslaughter.

The case hinged on the fact that there was damage to the front of the Simca and droplets of blood on the front bumper. John protested his innocence, but to no avail and after several hours of intense interrogation, during which he later claimed he had been beaten by the police, he confessed. Within hours he recanted, saying that he had only admitted guilt in an effort to end the interrogation and stave off another beating. In his defence John claimed that the damage to the car had been incurred weeks earlier and that the blood on the bumper resulted when he brushed past it when carrying Rosemary to the car. But the confession and the forensic evidence was sufficient to convict him. John was condemned to serve ten years' hard labour in Australia's notorious Fremantle Prison.

Seven months later, John thought his luck had turned when a prisoner informed him that a new inmate was boasting that he had intentionally killed a young girl for the fun of it in John's neighbourhood on the night in question. The driver was Eric Edgar Cooke, a psychopath who had been sentenced to death for a series of brutal murders. The police took Cooke to identify where he had run Rosemary down, but he pointed out the wrong place and so John's appeal was turned down. Cooke again confessed to Rosemary's murder on the morning of his execution, but it was not sufficient to free John Button, who was eventually released after five years in 1968 for good behaviour.

FREEDOM IS NOT ENOUGH

Free, but unable to live with the stigma of being labelled a convicted killer, John determined to clear his name. He found an unlikely ally in Estelle Blackburn, a female journalist who had been dating his brother. She was able to access files that had been closed to John and to interview people who would not talk to him about the case.

Estelle discovered that Cooke had confessed to six hit-and-run murders, but that this information had not been introduced at John's appeal. Convinced that John was innocent, Estelle enlisted the help of W. R. 'Rusty' Haight, an expert in the new forensic science of Pedestrian Crash Reconstruction, which Rusty liked to describe as 'common sense mixed with basic physics'.

Using a properly weighted and articulated bio-medical dummy suspended from a fishing line, which broke on impact, and a lightweight French Simca identical to John's car, Haight proved that the damage to the car was inconsistent with the injuries sustained by the victim. Rosemary had been hit at 48km/h (30mph), which leaves distinctive markings on the vehicle as the body folds around the front of the car with the head impacting on the bonnet to leave a noticeable dent. John's car did not have this damage when the police impounded it. Furthermore, Haight managed to obtain a 1963 Holden which was the car Cooke had driven when he claimed to have killed the six women. When the dummy was hit by the Holden it landed on its back in the position John claimed to have found Rosemary in, whereas when the Simca hit it the dummy landed on its face.

But one last question needed to be answered before the new evidence could be admitted in an appeal. Cooke's car had a plastic visor to shield the driver from glare and the police had always maintained that if Cooke had killed Rosemary the visor would have been damaged. But Haight was able to demonstrate that the flexibility of the plastic visor meant that it snapped back into shape after the impact.

Armed with this compelling evidence and Estelle Blackburn's best-selling book on the case, Button's lawyers were able to argue successfully that the original prosecution case was fatally flawed. It was only in 2000 that John Button was finally exonerated of the manslaughter of Rosemary Anderson having, in his words, been 'imprisoned by the injustice of the whole affair' for the previous 37 years.

Eric Edgar Cooke was sentenced to death for a series of brutal murders

Even those who have no patience with convoluted conspiracy theories must surely question the official government version of the John F. Kennedy assassination as presented by the Warren Commission, which concluded that a lone marksman was responsible for shooting the president and was then himself conveniently killed before he could be questioned in open court. Quite apart from the numerous inconsistencies, accusations of evidence-tampering and mysterious deaths of key witnesses, the forensic evidence alone challenges the idea that a single sniper killed President Kennedy in Dallas on that fateful November afternoon in 1963.

If the assassination was indeed orchestrated by disaffected elements within the administration and the armed forces, as has been alleged, those responsible covered their tracks extremely well, but they could not have foreseen that the fatal moment would be captured on film by amateur home movie buff Abraham Zapruder.

Despite several attempts to suppress the controversial footage, those images could not be airbrushed out of history like the numerous witnesses who swore to hearing shots and seeing puffs of gunsmoke coming from a location other than the Dallas Book Depository where the lone gunman, Lee Harvey Oswald, is generally supposed to have fired three uncannily accurate shots in quick succession from a faulty bolt-action rifle, a feat even trained snipers failed to copy in subsequent tests.

The Zapruder footage establishes a timeframe of 5.6 seconds from the first shot, when Kennedy is clearly seen to flinch, as he instinctively reacts to the bullet whizzing past his ear, to the last in the frame which quite clearly shows the front right side of the president's head being smashed by a bullet.

The bullet obviously could not have come from the direction of the Book Depository which the motorcade had just passed. And this is when the myth of the 'magic bullet' was born. One of the most famous scenes in Oliver Stone's film JFK is the monologue on the subject of the magic bullet.

A model reconstruction to try to determine the path of the gunfire that killed JFK

UNBELIEVABLE FACTS

If there were only three shots, as the Commission contends, then the first was the one which made Kennedy instinctively react and Senator Connally turn round in the front passenger seat to see what had startled the president. This first bullet appears to have ricocheted and a fragment of it, or piece of shrapnel, then struck bystander James Teague, who was standing by the underpass in front of the motorcade. If the third bullet caused the fatal head wound, then that leaves only one bullet responsible for the seven separate wounds in Kennedy and Connally. According to the Commission this 'magic bullet' entered the president's back at an angle of 17 degrees and was deflected upward and out through the president's neck, then suspended for 1.6 seconds after which it turned right and then left and entered the Senator's right armpit. It then headed downwards at an angle of 27 degrees, shattering Connally's fifth rib, and exited from the right side of his chest. We are then asked to believe that the bullet made a right turn and shattered Connolly's radius bone in his right wrist, after which it made a U-turn and buried itself in the Senator's left thigh.

Incredulity is stretched beyond breaking point by the assertion that this miraculous projectile then dropped out of the wound unnoticed and was later discovered in pristine condition on a stretcher at Parkland Hospital, where it proved a perfect match for Oswald's weapon. The Army wound ballistics experts at Edward Arsenal later fired identical rounds for comparison and all were severely distorted after striking just one bone in a cadaver.

Any forensic pathologist would know that the only possible explanation for the number of wounds and their angle of entry is that there were four shots, not three, and that would require at least two marksmen, maybe even a third. A triangulation of fire is standard set-up for a moving target in US 'black operation' assassinations. It establishes a killing zone that reduces the risk of the target escaping alive and is indicative of a CIA or military involvement. A ballistics expert who studied the location could see that a single assassin would have had a perfectly clear shot from the rear of the Book Depository as the motorcade passed slowly towards him along Huston and possibly even time for a second shot, whereas the view Oswald is said to have had of the president's car as it turned into Elm Street at the rear of the Depository was obscured by an enormous tree which retains all its foliage in autumn. Clearly someone in the conspiracy did not do their homework and reckoned without the tenacity of those who refused to take the official version at face value.

ANOMALIES AT THE AUTOPSY

At Parkland Hospital, Dallas, where the preliminary autopsy was carried out, no fewer than 26 medical personnel were witness to the fact that the back of the president's head had been blown away in a manner which could only have been caused by a shot entering the right side of the head. One of the attending physicians, Dr Peters, later testified that the wound was 7cm (23⁄4in) in diameter and that 'a considerable portion of the brain was missing'. Another observed that as much as a fifth or even a quarter of the back of the head had been blasted out and that a large fragment of skull remained attached to a flap of skin, also indicative of an exit wound.

Incredibly, the pathologist in attendance at the preliminary examination was asked to concentrate exclusively on the head wound and not to dissect the neck, which would have revealed the presence of a second bullet wound. Significantly, all of the civilian doctors who were present regarded the hole in the throat as an entry wound, but it was disregarded by the chief pathologist, Commander Humes, who, under instructions from the military observers, abruptly wound up the examination, to the consternation of the resident physicians. Humes is said to have later burned his autopsy notes.

The body was then transferred to a military base where it was examined by service physicians who would not have been free to publish their findings and who were under orders to prepare a report for the eyes of designated officers only. More revealing and disturbing is the fact that later the same day, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered the immediate cleaning and repair of the presidential limousine, thus destroying crucial fragments of physical evidence including the bullet holes from which the angles of trajectory could have been calculated.

And many years later, when conspiracy-obsessed New Orleans DA Jim Garrison obtained a court order in order that he could examine the president's remains in the National Archive to determine the direction of the bullets, he was told by officials that the president's brain had been lost!

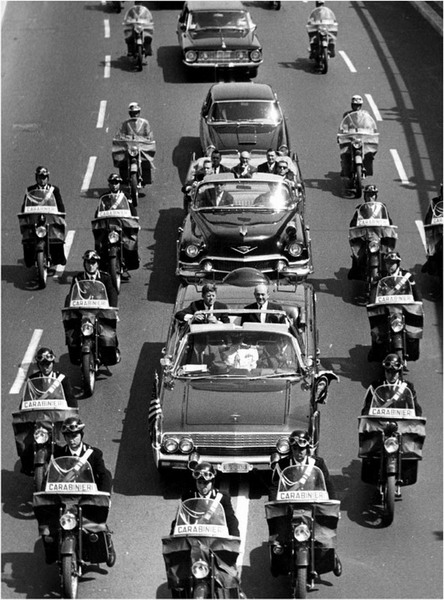

The presidential motorcade moments before the fatal shooting

When a home-made pipe bomb killed 17-year-old Chris Marquis in his home in Fair Haven, Vermont, detectives had little hope of catching the killer and that was because the lethal ingredients were common household items that could be purchased anywhere in the United States.

Neighbours often joked that Chris and his mother lived in the safest house in town – a bungalow right next door to the local police station. But one morning in March 1998 violent death came to Fair Haven in an innocuous-looking package. Christopher's mother suspected nothing as she carried the parcel to her son, although she didn't recognize the name of the sender or the return address. Chris ran a small CB radio sales and repair business from his bedroom and this looked as if it might be something that he had ordered from a supplier. But Chris didn't recognize the sender either. He opened it anyway and the next moment there was a tremendous explosion which tore a hole in Chris's leg and left his mother with serious injuries. Chris later bled to death in hospital, leaving his mother distraught and wondering who could have wanted her son dead and why.

Detectives soon had an answer to both questions. On Chris's computer, investigators found emails from angry customers claiming that Chris had cheated them by advertising an expensive radio over the internet and then sending a cheaper model in its place once he had cashed their cheques and pocketed the difference.

Suddenly they had several hundred suspects. But could any of them really have been so angry that they would take revenge by killing a 17-year-old that they had almost certainly never met?

While detectives trawled through the list of Chris's customers, forensic experts combed the bungalow looking for physical evidence that could give a clue as to the identity of the perpetrator. They found Styrofoam packaging material and pieces of pipe, wire, grains of smokeless gunpowder and tiny hex nuts – all ingredients of a homemade pipe bomb, but nothing that pointed to a specific individual. The return name and address on the package proved to be fictitious and none of Chris's outraged customers lived in Mansfield, Ohio, where the package had been posted.

The mother of bomb victim Chris Marquis with a photo of her son

A LUCKY BREAK

But then they had a break. The story had made the national news and someone had phoned in with information. This anonymous source had recently been in a bar where he had overheard a long-distance truck driver complaining that he had been ripped off by a mail-order CB radio repair service in Vermont and was planning to go down there and teach the guy a lesson. The truck driver's name was Christopher Dean.

The detectives went to Dean's house in Indiana, where they found hex nuts of the type and size used in the bomb, lengths of wire and even a plastic funnel with grains of what proved to be smokeless gunpowder residue. But again, these did not amount to conclusive proof.

To find out if the hex nuts in Dean's house were the same as those found at the crime scene, forensic scientists took scrapings of both samples and placed them in a neutral solution before putting them in a plasma atomic emission spectroscope which vapourized the samples at an extremely high temperature. Different compounds such as zinc and copper vapourize at different speeds, revealing the chemical make-up of any metallic object, and computer analysis of the test results revealed that both sets of hex nuts had exactly the same chemical make-up. The residue of gunpowder found in the funnel was then analyzed by a scanning electron microscope which uses X-rays to identify the components of a given substance and it showed that the powder at both sites had a 17 per cent nitroglycerine content as well as a stabilizing agent, nitro cellulose.

Crude pipe bombs, as seen here, can have a devastating effect on life and limb

However, even this was considered not enough to convict, so detectives returned again to scour the bungalow at Fair Haven. This time they found a 9-volt battery used to detonate the bomb. On the underside was printed a sequence of letters and numbers which subsequently proved to be an identification code relating to a specific batch made on a particular day at a particular factory. Police later found an open packet of 9-volt batteries at Dean's house with the same batch numbers. One battery was missing.

And the final nail in Dean's coffin was the discovery of a file containing the fictitious return name and address in his computer. He had evidently deleted the file but wasn't aware that by printing the label he had created another file which could easily be recovered from the hard drive. Dean had assumed that no one would ever connect him with the bombing because he had never been to Fair Haven and had never met the victim. He was wrong and now has a lifetime in prison to regret it.

Truck driver and pipe bomber Christopher Dean at the time of his arrest

Even the smallest fragment of evidence might prove to be the crucial clue that ultimately solves a case. The crash of Pan Am Flight 103 on 21 December 1988 is a prime example of how a major case can be solved by an apparently insignificant item.

A year after Pan Am Flight 103 had been blasted out of the sky over the remote Scottish town of Lockerbie investigators were no nearer to solving the case than they had been on day one. The tragedy had initiated one of the most exhaustive investigations of recent times with 200,000 fragments recovered from the debris of the town and the surrounding countryside. The only certainty was that an explosion had ripped through the plane's cargo bay and that it appeared to have been caused by a bomb as pieces of a triggering device had been found. But they were at a loss to say who might have been responsible.

It was by chance that a man out walking his dog happened to notice a small piece of grey fabric torn from a T-shirt near the crash site and brought it to the local police in the hope that it had a connection with the crash. The label was intact which led detectives to the owner of a small clothing shop in Malta. Incredibly the owner was able to give them a detailed description of the customer because the man had behaved oddly, buying several items without considering the style or size.

Chemical analysis revealed that the T-shirt had been used to wrap the bomb, but, more significantly, a shard from the circuit board bearing the number '1' was imbedded between the fibres which helped detectives to identify the timing device as a Swiss MST-13. When combined with other evidence, the fabric scrap and the fragment of circuit board led to the arrest of two Libyan agents working at Malta airport who had primed the bomb and sent it on to London using stolen luggage labels where it was loaded aboard the fateful flight.

Investigators examine the remains of Pan Am Flight 103

When 31 people died in a fire at King's Cross underground station in London on 18 November 1987, the authorities feared that it might have been the result of a terrorist bomb. The IRA were then active on the British mainland and the police needed to know as a matter of urgency if King's Cross was the first casualty in a new campaign of terror.

Although witnesses had reported seeing smoke billowing from beneath an escalator, suggestive of a small electrical fire, one of the victims had injuries that appeared to be consistent with those caused by an explosion. Fortunately, the pathologist in charge had considerable experience of both fire and terrorist attacks and was able to identify the wound to the young woman's leg as having been caused by molten debris. He ruled out a bomb but there was still the demanding task of identifying the cause of the blaze and reconstructing the sequence of events from clues to be found in the bodies. The nature of the injuries would tell the victim's stories now that they were no longer able to speak for themselves.

LESSONS TO BE LEARNED

It was critical to know if the deaths could have been avoided, not just for the sake of the bereaved families, but also for the future safety of the London Underground network. If there was a question of possible negligence the bereaved might be entitled to compensation or have grounds to sue those responsible. Health and safety officials would also have to learn from the disaster to ensure it could never occur again.

Forensically speaking, fires are not straightforward. Victims die in different ways, depending on where they are in relation to the flames and other factors. At King's Cross the pathologist's report revealed that some had died mercifully quickly in the vicinity of the fireball, which had generated heat around 1200° centigrade. However, it wasn't the heat that had killed them but the inhalation of cyanide created by the burning paint and ceiling tiles. Others were overcome by smoke, but many had simply been incinerated in the flashover and were found in the characteristic pugilist pose indicative of asphyxiation.

It emerged that the cause of the fire was a discarded cigarette or match which had dropped between the escalator treads and set alight oily rags or paper that had been allowed to accumulate under the escalator. The cause of the ensuing fireball remains a mystery, but the fire was certainly spread uncommonly rapidly by the huge draughts of air caused by the movement of the trains through the tunnels and by the anti-graffiti paint which acted as an accelerant.

But that wasn't the end of the matter. The pathologist's findings proved crucial in the case of fireman Colin Townsley, who had died trying to save passengers and been posthumously awarded the Queen's Gallantry Medal for Brave Conduct. Two years after his death his widow initiated a case for damages on the grounds that he had suffered 'pre-impact terror' which involves unnecessary suffering and asked for the forensic report to support her claim. The autopsy revealed that the fireman had not sustained severe burns but had died from the inhalation of fumes. He must have been conscious for several minutes and therefore aware of the fact that there was no hope of escape and that death was inevitable.

The cyanide vapour created by the burning paint and ceiling tiles had been such a deadly contributing factor that, in the aftermath of the disaster, flame-retardant paint became standard and a sprinkler system was installed. In addition all the old wooden escalators on the London Underground were ripped out and replaced by those made of metal. And as a further precaution smoking was banned throughout the underground system. Lessons had been learned, but at a terrible cost.

Underground damage: the top of the escalators at King's Cross after the fire

Policemen emerge from the charred remains of the tube station at King's Cross