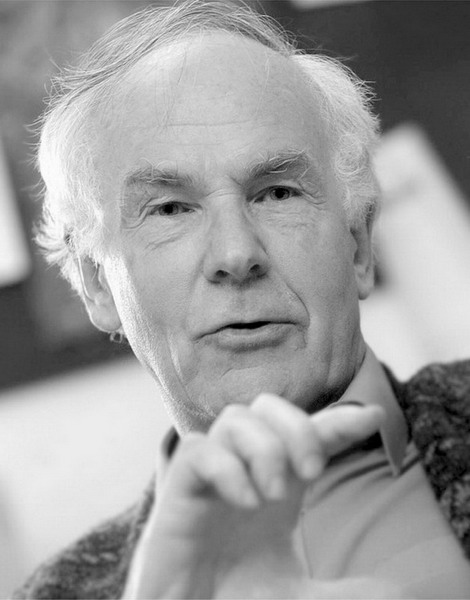

Yves Montand whose body was exhumed to determine a paternity lawsuit after his death

There have been several high-profile miscarriages of justice in recent years, where an eagerness to secure a conviction has led to some questionable verdicts that have, on appeal, eventually been overturned and the defendants allowed to walk free. Forensic science is only as effective as the people who use it and, if they are blinded by ambition, professional pride or are simply incompetent, they can manipulate data and results as effectively and to the same destructive end as any criminal. Forensic techniques can be manipulated to create a false impression, as in cases of fraud and forgery but, in the right hands, science will ultimately reveal the truth.

Forensic science is not solely used for solving crimes. It is also now routinely employed in civil actions when there is a question of negligence which, if proven, can result in awards totalling millions of pounds in compensation. Such cases would include claims for accidental injury against employers or local authorities as well as against private companies who may be responsible for the illegal dumping of toxic waste into public drinking water or onto sites designated for development.

A culture of litigation has always existed in the US, but since the 1990s there has been an unprecedented growth in civil actions across Europe and as a result numerous private laboratories have been established offering expertise to parties who feel that they failed to secure justice through the criminal justice system and are now forced to pursue cases for compensation through the civil courts. In the US, the O. J. Simpson case is one notable example (see here). But the motive is not always financial nor even the pursuit of justice.

Yves Montand whose body was exhumed to determine a paternity lawsuit after his death

Several high-profile paternity suits have recently been determined using the same DNA analysis techniques that were originally developed to secure criminal convictions. In several cases the subject of the action was deceased when the test was carried out. The French actor Yves Montand, for example, was disinterred in 1998, seven years after his death, to allow DNA to be extracted so that a potentially costly lawsuit could be avoided and the matter of paternity resolved. DNA analysis was also recently employed to prove or disprove rumours that America's founding father and third president Thomas Jefferson had fathered an illegitimate child with his young black slave and companion Sally Hemings. DNA proved the truth of the allegation and a small but significant footnote will need to be added to all future biographies of the great man. A similar mystery surrounds George Washington, the first US President, who is thought to have fathered a child with a black slave living on his brother's estate. But while the girl's descendants are willing to donate DNA to settle the matter, the FBI have failed to recover sufficient genetic material from locks of Washington's hair to carry out the test.

Both fictional and factual TV crime series give the false impression that forensic science is infallible and for that reason miscarriages of justice are now a thing of the past. But that is simply not true. Science is only as good as the scientists who use it, and sadly there are many recorded cases of pathologists, medical examiners and laboratory technicians who have repeatedly failed to interpret and present the evidence in the correct way, through negligence, arrogance or, in rare cases, even wilful falsification of their findings to enhance their own reputation.

In 2005 several women who had been wrongly imprisoned for murdering their own children in the so-called 'shaken baby syndrome' cases had their convictions quashed by the British Court of Appeal because the testimony of forensic paediatrician Professor Sir Roy Meadows was considered unreliable.

Professor Meadows whose expert evidence was discredited

In 1991 the Birmingham Six, who had been falsely imprisoned for the IRA pub bombings of mainland Britain in 1974, were finally freed after spending almost 20 years in prison when it was accepted that the method of testing for explosive residue at the time of their trial was flawed. It transpired that the technique used for detecting nitroglycerine, known as the Griess test, would also register positive for other common substances such as nitro-cellulose which is a chemical used in the manufacture of playing cards and cigarette packets. Several of the suspects had been smoking and playing cards just prior to their arrest.

Confessions were allegedly beaten out of them, but at an earlier appeal hearing the judges are said to have deliberately ignored both accusations of police wrongdoing and the results of a later, far more reliable chemical test because they could not admit to the possibility that the British judicial system was not perfect.

These are only a handful of high-profile cases that made the headlines. To list all the modern miscarriages of justice that hinged solely on flawed forensic evidence would take a book all of its own.

Justice at last: the release of the Birmingham Six in 1991

A QUESTION OF INTERPRETATION

Such cases raise the question as to how far forensic scientists should go in interpreting their findings as fact and at what point interpretation of the facts becomes speculation. The facts should speak for themselves, but often the expert witness is asked to present a theory as the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

An extreme example is that of the Texas forensic psychiatrists who are asked to predict a defendant's future behaviour based on their past actions and the crime of which they are accused so that the jury can decide whether to recommend the death penalty or life imprisonment. While it may be possible to predict a person's future criminal behaviour, that prediction is conditional on the quality of the expert witness.

In Dallas, Texas forensic psychiatrist Dr James Grigson acquired the nickname 'Dr Death' because his assessment was frequently the deciding factor in whether a convicted person should live or die. But in 1977 Grigson testified that defendant Randall Dale Adams, who had been found guilty of murder, possessed a 'sociopathic personality disorder' and that he would, without doubt, kill again.

In fact, Adams was subsequently found to have been innocent of the crime of which he had been accused and had never killed anyone. Dr Grigson had evidently used his experience to speculate on the state of mind and future behaviour of the person who had committed the murder and not the person sitting opposite him in the courtroom on trial for his life. Mr Adams was released just three days before his scheduled execution.

Unfortunately, in the state of Texas many men and women whose convictions are likely to be judged unsafe over the next few years will not walk free for the simple reason that they have been executed on the questionable findings of pathologist Ralph Erdmann and forensic serologist Fred Zain, who together are thought to account for several thousand wrongful convictions.

The cases of Erdmann and Zain are unrelated, but it is surely no coincidence that both occurred in the Lone Star State where there is abnormal pressure on forensic scientists to serve the interests of one party or the other in a prosecution because the ever-present spectre of the death penalty raises the stakes to a degree where there is absolutely no margin for error.

Zain only came to the attention of diligent public defender George Castelle because his record was simply too good to be true.

Between 1977 and 1993 Zain was called to testify at hundreds of rape and murder trials because he produced the results prosecutors needed to secure a conviction, often identifying blood and semen stains previous examinations had failed to find. The greater his reputation grew, the more cases he was given and these included many in neighbouring states. It was only in 1992 after a wrongly convicted man, Glen Woodall, successfully sued the state of West Virginia for wrongful imprisonment that Zain's ineptitude came to light.

Woodall had served five years for a rape he did not commit because Zain had testified that the semen recovered from the victim proved that the assailant's blood type was the same as Woodall's. While it may have been the same type, that does not necessarily mean that it was Woodall's blood.

The extent to which Zain's shoddy science impacted upon innocent people's lives was highlighted in a subsequent investigation, that of the black athlete William Harris.

The Harris case is a particularly disturbing example of how a misplaced faith in the infallibility of forensic science can sidetrack the justice system and cloud the judgment of those involved in the investigation. In 1985 Harris, a talented high-school student with a promising future in athletics, was accused of rape despite the fact that the victim had categorically ruled him out as her attacker from a photo line-up.

Harris had only been included in the line-up because he fitted the general description as being 'young, black and athletic'. This significant detail was not presented at trial and in fact the witness subsequently identified Harris as her attacker in court, having apparently been persuaded by the flawed forensic evidence that she must have been mistaken in initially ruling him out. Harris spent seven years in prison until DNA evidence finally proved his innocence.

At the conclusion of its investigation into Zain's career the West Virginia Supreme Court declared that Zain's 'systematic' errors involved 'overstating the strength of results … reporting inconclusive results as conclusive,' and 'repeatedly altering laboratory records'.

But incredibly this catalogue of ineptitude was not an isolated incident. During the 1980s, while Zain was building an undeserved reputation for getting results, a colleague in the same state was abusing the trust placed in him with equally disastrous results. Forensic pathologist Dr Ralph Erdmann was fabricating autopsy reports, mislaying body parts and falsifying evidence which resulted in many murder victims being certified as having died from natural causes and their killers escaping capture. He was not only lazy and incompetent, he was also revealed to be over-eager in the extreme to please his employers and to produce the results they wanted.

Dr Erdmann's systematic abuse of his privileged position was only discovered when a bereaved family questioned his autopsy report which stated that he had removed and weighed the spleen of their loved one, a procedure that would have been impossible in this particular case as the deceased had had their spleen surgically removed many years before. As the prosecutor observed at the end of the investigation into Dr Erdmann's iniquitous career, 'If the prosecution theory was that death was caused by a Martian death ray, then that was what Dr Erdmann reported.'

But it wasn't the deceit or wilful negligence which had brought about his downfall. That had only led to the revoking of his medical licence and a demand for the repayment of his autopsy fees. Dr Erdmann was only put behind bars in the late 1990s when police found an M-16 assault rifle and a small armoury of other weapons at his home which violated the provisions of his probation.

A scientist places test tubes in the centrifuge for analysis

When German investigative journalist Gerd Heidemann was offered a cache of Adolf Hitler's unpublished personal diaries, written in the Führer's own hand, he couldn't believe his luck. The Nazi leader's personal papers were believed to have been destroyed in April 1945 when the plane carrying them out of besieged Berlin was shot down over Dresden. No one had expected them to resurface.

So eager was Heidemann to secure the scoop of the century that he committed the cardinal sin of journalism – he failed to question the legitimacy of his source. Had he done so he would have discovered that the man he was so keen to do business with was a convicted forger.

Konrad Kajau had begun his criminal career forging luncheon vouchers, but quickly progressed to paintings before finally graduating to manufacturing Nazi memorabilia, for which there was a lucrative worldwide market.

Posing as a wealthy collector, Kajau conned Heidemann into believing that he was acting as an agent for an East German army officer who could not be named for fear of being sent to Siberia by his Russian superiors for smuggling a national relic to the West. Heidemann and his boss at Gruner and Jahr, one of Germany's leading magazine publishers, would have to take it on trust that the diaries were genuine and make a bid, or risk the offer being withdrawn.

So, on 18 February 1981, Heidemann attended a secret meeting with publishing director Manfred Fischer at which Fischer and his fellow executives approved the purchase of 27 diaries and several other manuscripts comprising the unpublished third volume of Hitler's autobiography, Mein Kampf, for the equivalent of $2million.

It was only after the delivery of the manuscripts that the triumphant journalist and his bosses thought it prudent to have them properly authenticated, but even at this crucial stage they made another fateful mistake. They handed over the diaries to two forensic experts who were, to say the least, not the ideal choice. Ordway Hilton was an American documents expert who was unfamiliar with Germanic script and Swiss forensic scientist Max Frei-Sulzer was a microbiologist. Crucially, neither was aware that some of the samples of Hitler's handwriting that they had been given to compare were themselves forgeries, created by the very same hand, that of Kajau.

DOUBTS SET IN

Once Gruner and Jahr convinced themselves they had established the authenticity of their latest asset, they began probing abroad for publishing partners, initiating a bidding war between Rupert Murdoch's global media empire and American giant Newsweek. Naturally both parties wanted to be certain they were buying the genuine article and so brought in their own experts. Murdoch sent noted historian Hugh Trevor-Roper to Switzerland to examine the documents, knowing the English academic's name would carry weight with scholars and the foreign press, but Trevor-Roper later claimed he felt overwhelmed by the sheer volume of material and also pressured by both parties to overlook glaring historical discrepancies which originated in a book published in 1962. He overcame his doubts and declared himself satisfied the documents were genuine.

But even while Trevor-Roper wrestled with his reservations German forensic experts were subjecting samples to stringent chemical analysis. Their findings were conclusive and damning. A simple ultraviolet test revealed that both the paper and bindings had been bleached with a chemical called blankophor which was not in use until the 1950s, while the official Nazi seals contained traces of viscose and polyester, both of which did not exist during the Second World War. Even the ink was modern and, when subjected to a chloride evaporation test, revealed that the diary entries had been written just a year before.

The fraud was exposed in open court where both Heidemann and Kajau received prison sentences of just under five years, Kajau being found guilty of forgery and Heidemann of misappropriating his employers' money.

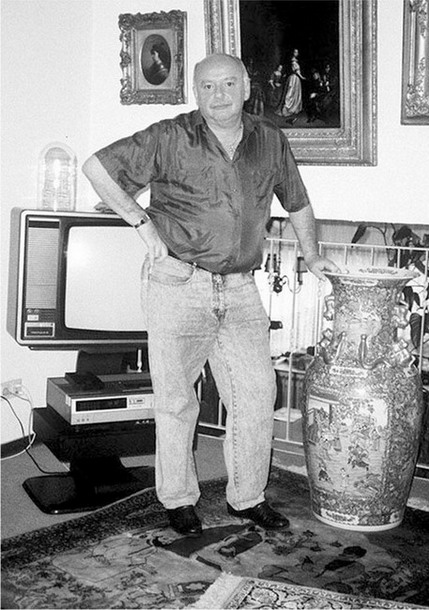

Sentenced for forgery: Konrad Kajau

It sounds like a scene from Psycho, but the case of the mummified corpse kept in a cupboard in a Welsh boarding house is one of the most bizarre true-crime cases on record. And the most extraordinary aspect is that the alleged murderer was not a psychopathic serial killer but the victim's middle-aged landlady, who lived with the grisly secret for 20 years before dissension among the experts prevented her conviction for murder.

The mummified remains were accidentally uncovered in April 1960, when the landlady's son broke into the locked cupboard on a landing to clear out what he believed were a former tenant's belongings. When his mother, Mrs Sarah Harvey, returned from a short stay in hospital she found the cupboard bare and police officers waiting to interview her. At first Mrs Harvey struck the police as a harmless old lady as she told them her lodger, Mrs Frances Knight, had moved out in April 1945 about the same time that a couple had asked her to store some of their personal belongings, then left taking the cupboard key with them.

The ailing, enfeebled figure elicited the sympathy of detectives who dutifully followed up the false leads she had given them, but when neither Mrs Knight nor the fictitious couple could be traced, the police ordered an autopsy to determine the identity of the corpse. However, it wasn't as simple as they hoped. Although the body was in a remarkable state of preservation thanks to a constant stream of warm, dry air which had retarded decomposition, the pathologist was unable to confirm it was the body of Mrs Knight. Dental records were of no use as the victim had false teeth and these had disappeared along with a wedding ring which might have proved identity. All that could be said with certainty was that the body was that of a white female aged between 40 and 60, who had been 163cm (5ft 4in) tall, right-handed and walked with a limp. Moreover, she shared the same blood group as members of Mrs Knight's family.

AN ODD STORY

It was clearly the mummy of Mrs Knight, but without a positive identification it could not be stated as a fact in a court of law. Fortunately, Mrs Harvey broke down under questioning and admitted that she had concealed the body in a state of panic. But what reason could she have had for fearing anyone would have queried her version of events if Mrs Knight had died of natural causes as she claimed?

Harvey alleged that Mrs Knight had collapsed in her room on the day she died. Unable to lift her onto the bed, Harvey left her lodger on the floor. Yet when had she returned to find her lodger had died, she had miraculously found the strength to drag the body into the hall and stuff it into the cupboard along with a mattress to soak up the seeping body fluids.

However, she couldn't explain the stocking that had been tied around the neck of the corpse with a knot so tight that it had left a groove around the throat and an impression on the thyroid cartilage.

It appeared that Mrs Knight had been strangled, yet at the trial various forensic specialists disagreed as to the manner of death, with one even suggesting that she might have hanged herself and another that there was no evidence that the stocking had been tight enough to act as a ligature. The impressions on the neck, he argued, might have been caused by swelling in the neck postmortem. Yet even if Mrs Knight had taken her own life, there would have been no reason for Mrs Harvey to conceal her body and in so doing bring suspicion upon herself.

With dissension among the experts, the judge was forced to direct the jury to find Mrs Harvey not guilty of murder. In the end she was convicted of fraud and sentenced to 15 months for having deceived Mrs Knight's solicitors into believing that the old lady was still alive so that she could draw her £2 maintenance payments every week for almost 20 years.

65-year-old grandmother Sarah Harvey was not all she seemed

Dr Josef Mengele's insatiable appetite for cruelty exceeded that of the most cold-blooded mad doctors of pulp fiction. The murderous Nazi was known as the Angel of Death because of his sadistic experiments on the helpless inmates of Auschwitz concentration camp, where he was personally responsible for the murder of 400,000 people, many of them children.

Mengele's name and the enormity of his crimes was unknown to the Allies when they liberated the concentration camps in 1945, allowing the 'Angel' to slip unnoticed through the chaos of post-war Europe and seek asylum in South America. It was only after the dramatic arrest and abduction of one of his colleagues, Adolf Eichmann, the architect of the 'Final Solution' from Argentina in 1961 to stand trial for war crimes that the search for Mengele was intensified. But it would be another 24 years before one of the most notorious mass murderers of modern times was finally captured.

In 1985, impelled by a fresh American initiative to bring Mengele to justice, two German expatriates domiciled in Brazil offered to take investigators to what they claimed was the burial site of the world's most wanted war criminal.

Naturally, both the American and German authorities demanded that their forensic experts be allowed to examine the remains and determine the identity of the man who had been buried under the name of Wolfgang Gerhard. But there was an additional group with claims to a special interest in the outcome – associates of the celebrated Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal, who had himself been brutalized in Auschwitz. Together the three parties assembled a distinguished team of experts who travelled to the remote Brazilian town of Embu on 6 June 1985.

There they exhumed the coffin and examined its contents which were evidently those of a white, right-handed elderly male between sixty and seventy years of age. These basic facts could be determined by the narrowness of the pelvis, the shape of the skull, the comparatively longer bones on the right side and the degree of wear of the teeth and specific bones. A more accurate estimate of the age of the skeleton was indicated by the multitude of microscopic canals in the femurs which carry the blood vessels. The amount and condition of these indicated a man in his late sixties which would correspond to Mengele's age. The length of key bones gave a reliable height for the corpse of 173.5cm (5ft 71/2in), half a centimetre short of the height recorded in Mengele's SS file.

But his dental record proved to be of little use as it was hand-drawn and light on detail, although it indicated a pronounced gap at the front of the upper palate which resulted in a characteristic gap-tooth grin. An X-ray of the skull confirmed that Herr Gerhard had possessed the very same distinctive feature.

In the final stage of the examination the skull provided the conclusive evidence that even the conspiracy theorists could not question. Using a technique known as video superimposition, German forensic anthropologist Richard Helmer overlaid a photograph of the skull onto archive photographs of Dr Mengele to reveal 30 key features that were a positive match.

Nevertheless there were those who feared the Angel of Death had eluded them yet again.

Then in 1992 the advent of genetic fingerprinting made it possible to compare DNA from the remains in Embu with a sample taken from one of Mengele's living relatives. There could be no doubt. The bones in Brazil were those of Dr Mengele.

There can be no doubt that had Scotland Yard possessed the tools and techniques of forensic science at the end of the 19th century they would have been able to identify and apprehend the first serial killer of modern times – Jack the Ripper. As it was, the routine fingerprinting of criminals was still several years in the future, basic blood grouping remained to be discovered and the value of trace evidence had still to be fully appreciated by the Metropolitan Police and proven in an English court of law.

Forensic detection was in its infancy in 1888, when the Ripper stalked the gloomy streets of Whitechapel disembowelling prostitutes before disappearing into the thick London fog. But he left several clues behind. At the site of the first murder, in Buck's Row, where he slit the throat of Mary Ann Nichols, the official records state that no significant clues were found, yet it is inconceivable he did not leave footprints in the grime and mud which could have been photographed, or at least sketched, so they could be compared with shoes belonging to the prime suspects.

THE BODY COUNT RISES

A month later, on 8 September, the body of Annie Chapman was discovered in a back yard at Hanbury Street, Spitalfields, with an envelope by her head and her meagre personal belongings arranged neatly at her feet as if part of a crude funeral ritual. All of these items might have preserved the killer's fingerprints. A leather apron, of which much was made at the time, proved to belong to a resident of the tenement. But little was made of the fact that her cheap brass rings had been wrenched from her fingers, suggesting that the killer mistook them for gold – an error an educated man would not have made. If the police had only thought to search their suspects' lodgings, they might have quickly wrapped up the case.

The nature of the mutilations and depth of the wounds led pathologist Dr George Bagster Phillips to conclude that the killer had some degree of medical knowledge. The Ripper had taken between 15 minutes and an hour to perform his hideous surgery, which led the coroner to speculate he might have experience of the post-mortem room, another observation which could have helped the police to narrow their shortlist of suspects.

As the hunt for the Ripper intensified, the body of Elizabeth Stride was found in Dutfield Yard off Berner Street on the morning of 30 September and later that same day a second victim, Catharine Eddowes, was discovered in Mitre Square. In nearby Goulston Street the Ripper had discarded a piece of bloodied cloth torn from Eddowes' apron on which he had cleaned his knife. Chalked on the wall above it were the words, 'The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing'. Fearing this might incite an anti-Jewish riot, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren had it removed.

Had he delayed until a photograph could be taken, posterity would have been availed of perhaps the most significant and revealing clue of all, assuming of course that the writing was in the Ripper's own hand.

AN EYE-WITNESS DESCRIPTION

At the scene of the last and most hideous murder in Miller's Court, where he dissected the body of Mary Kelly in a frenzied travesty of an autopsy, there must have been a wealth of trace evidence, hair, fibre and fingerprints, as the murder took place inside the victim's lodgings.

It is believed the killer may even have left behind a red handkerchief a witness had seen him give to Mary only an hour before, which a family member or friend might have recognized had the fact been publicized.

The detailed description which the eye witness gave of the man he saw soliciting Mary minutes before her death should have been sufficient to identify the Ripper, but even allowing for the fact that Scotland Yard had only recently formed its formidable Criminal Investigation Department (CID) they seemed curiously incapable of coordinating the eye-witness testimony and physical evidence so that they could at least eliminate some of their prime suspects. All of these crucial clues were overlooked or undervalued due to the laborious, unscientific method of crime detection which still prevailed in the UK at the time, and the stubborn belief that the way to catch a criminal was to apprehend him in the act.

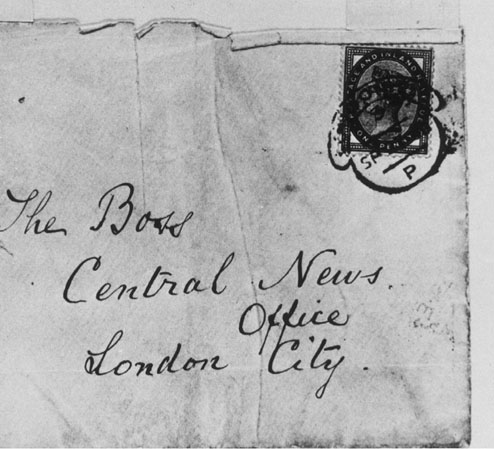

Fragment of one of the most crucial overlooked clues in the history of crime

POLICE LED ASTRAY

The police were further hampered by fictitious letters purporting to be from the Ripper which a modern forensic handwriting expert could have dismissed as bogus after a few hours' study. Instead they distracted detectives and drained much-needed resources. A third letter containing a note and part of a human kidney may well have been from the Ripper, but without a fully equipped forensic laboratory of the kind Edmond Locard was to establish in France in 1910, Scotland Yard was groping in the dark.

The other practical problem with which the police had to contend was the fact that sex killers were, and still are, notoriously difficult to catch because they are impulsive, erratic individuals who rarely conform to a predictable pattern of behaviour. It wasn't until the development of forensic profiling that a psychological sketch of the Ripper could be created based on his choice of victims, the nature of the mutilations and the location of the crime scenes.

In 1988, on the centenary of the Whitechapel murders, FBI agents Roy Hazelwood and John Douglas studied the documented evidence and concluded that the Ripper was probably a young white male whose volatile temperament and predisposition towards violent antisocial behaviour would have brought him to the attention of the police prior to the murders. He might therefore already have a conviction for affray or assault which would have been on file.

The fact that all the murders took place between midnight and 6am suggests that he lived alone, probably within 1.5–3km (1–2 miles) of the crime scenes as he knew the area well enough to escape undetected. Predatory killers usually begin stalking their prey in the vicinity of their own homes or place of business, moving further out as their confidence grows. In contrast to the slumming aristocrat depicted in popular fiction, he would have been of unkempt appearance and was likely to have been employed in mundane labour with little or no contact with the public, such as a slaughterman or dock worker.

And so the conclusion has to be that it was not the lack of physical evidence or eye-witness descriptions but the inability of the authorities to understand the significance of what they had and to act upon it that allowed Jack the Ripper to become the most enduring mystery in criminal history – the archetypal 'one that got away'.

Dr Sam Sheppard and his wife Marilyn were the image of the all-American couple. Dr Sam, as he was known locally, was an even-tempered young man of considerable personal charm with a profitable practice as an osteopath in Bay Village and a large executive-style home in a leafy suburb of Cleveland which the couple shared with their six-year-old son Chip. But their seemingly idyllic world was shattered when, on the night of 3 July 1954, Mrs Sheppard was found brutally beaten to death in the first-floor bedroom and her husband was accused of her murder.

Dr Sheppard claimed to have been asleep on the living room couch when he heard Marilyn cry out. Bolting up the stairs he had entered the bedroom where he was confronted by a shadowy figure who struck him over the head. When he finally recovered his senses, he stated that he heard the intruder escaping out the back door and gave chase. There in the darkness he saw the silhouette of a bushy-haired man who wheeled around and struck a second disabling blow from which he did not recover until the police arrived.

From the moment the Coroner, Dr Samuel Gerber, was put on the case he began questioning Dr Sheppard's version of events. To Gerber's eyes the scene appeared to have been staged, with drawers pulled out of a bureau and neatly stacked on the floor, Dr Sheppard's surgical bag emptied and placed in the hallway where it would catch the investigator's eyes and a bag of valuables stashed in a bush at the bottom of the garden. Inside the bag police found the doctor's blood-splattered self-winding watch which had stopped at 4.15am. Fingerprints had also been hastily erased, supporting the possibility that a third person had been present, but it seemed highly unlikely that an intruder could have failed to notice Dr Sheppard sleeping in the lounge and left him unmolested while he attacked his wife.

The finger of suspicion began to point to Dr Sheppard, and as the investigation dug deeper it emerged that both Sam and Marilyn Sheppard had had affairs. The whiff of scandal brought the local media baying for the doctor's blood. While the inexperienced local investigators dragged their feet and tried to cover up the fact that they had contaminated the crime scene in their carelessness, the local press demanded that their prime suspect be arrested. Before the week was out the press were setting the agenda and the subsequent trial seemed to be a mere formality.

For reasons best known to himself, Dr Gerber let it be known that the murder weapon was a surgical instrument. And it was this more than any other single piece of evidence which sealed Sheppard's fate. It later transpired that the murder weapon had not been found and that the coroner had made his assumption based on a suspicious 'shape' impressed in the pillow next to the body.

One thing that might explain Dr Gerber's stubborn refusal to face the facts was that he considered Dr Sheppard to be a thorn in his side. There was said to be personal animosity and distrust between the two medical men. Dr Sheppard was known to disapprove of the coroner's approach to forensic investigation and so bruised pride may have been a factor in Gerber's overlooking, and perhaps even suppressing, significant clues. It is known, for example, that evidence of forced entry at the doors to the basement was never presented in court. Furthermore, there were blood spots on the basement steps which had presumably dripped from the weapon as there were no indications the assailant had been injured.

Dr Gerber presented these blood spots as evidence of Dr Sheppard's guilt. At that time there was no available method of determining whose blood had been found, only whether it was animal or human. But Dr Sam's performance on the witness stand gave his defence counsel cause for concern. He recollected the horrific events with an almost academic detachment. When questioned about the events leading to the discovery of his wife's battered body, he remarked, 'I initiated an attempt to gather enough senses to navigate the stairs.'

Hardly the kind of tone one would expect of a bereaved husband.

Dr Sam Sheppard (left) is questioned by his nemesis Dr Samuel Gerber

Dr Sam's poor performance, together with Dr Gerber's testimony, helped to secure a conviction and a life sentence. However, the forensic evidence suggested that Sheppard might have been telling the truth. Although Marilyn had been repeatedly beaten until her face was unrecognizable the assailant had not used sufficient force to kill her. She had, in fact, drowned in her own blood. Dr Sheppard was a strong well-built man who could easily have killed someone with a single blow using a blunt weapon. Moreover, it is extremely unlikely that he would have bludgeoned his wife to death while their son slept in the next room, no matter how enraged he might have been. More revealing was the blood splatter on the wall and bedroom door to the left of the body which indicated spray from a weapon wielded by a left-handed assailant. Dr Sheppard was right-handed.

With such significant discrepancies a second trial was inevitable. At the retrial in 1964 the defence made much of Dr Gerber's failure to find the murder weapon, casting doubt on his assertion that it had been a surgical instrument. Greater attention was paid to the significance of the blood splatter and the 'flying blood' spray found on the inside of Dr Sheppard's watch strap, intimating that he had not been wearing it during the frenzied attack, but that it might have been in the possession of an intruder, as Sheppard had insisted.

It was suggested that the blood trail in the basement had been left by a casual labourer named Richard Eberling who had worked for the Sheppards and who was later incarcerated for killing several women. He was known to wear a wig to cover his thinning hair which might account for the bushy-haired figure Dr Sheppard claimed to have seen. Eberling even confessed, but his confession was dismissed due to his mental instability.

With more than sufficient reasonable doubt Dr Sheppard was acquitted the second time round, but ten years in prison had taken their toll. He left court a broken man, unfit to practise medicine, and died four years later.

However, his son continued to campaign to clear his father's name and in 1997 he filed a $2 million lawsuit against the state of Ohio supported by DNA evidence proving that the stains on the basement stairs were not his father's blood.

It appears that Eberling, a diagnosed schizophrenic, had become obsessed with Marilyn and must have killed her when she refused his advances. Dr Gerber, however, would not entertain the idea that he might have helped to convict the wrong man and there are those who even now still harbour doubts as to Dr Sam's innocence.