A victim of a shooting is stretchered away by paramedics

Nowadays there's no doubting the popularity of TV crime shows although they can give the false impression that forensic science is completely infallible. This in turn has brought increasing pressure on investigators who are having to become experts in one particular area of forensic detection to meet the higher expectations of juries who have to weigh the evidence. Investigations are no longer solved by a lone detective working on a hunch, but by a highly specialised team working closely together. But even the most damning evidence can be compromised by shoddy police procedures as high-profile cases such as the Nicole Brown Simpson homicide have revealed.

When a crime is committed, the first officers to respond are responsible for securing the scene and preserving it as they found it. This means ensuring that nothing is touched or moved so that any physical evidence is not compromised or contaminated. If there are victims displaying signs of life the police will call a team of paramedics to give on-site assistance, if they are not already there in response to the initial emergency call. The injured can then be removed to hospital, but the dead are left as they were found since vital clues can be obtained from studying the position and condition of the victim. Rigor mortis, for example, which occurs when the heart stops, depriving the muscles of oxygen, can give a clue as to the time of death, but can be broken if the body is handled, while lividity (the discoloration of the skin after death) could change if the body is moved.

In due course a designated crime scene officer will take control of the site, but until then, during the first vital minutes of an investigation, the officers will make preliminary observations and interview any witnesses who are at the scene. An attempt will be made to keep surviving victims calm and isolated so that they can be interviewed while the details and impressions are still fresh in their minds. They will also be discouraged from cleaning themselves up in case they have trace evidence on their clothes, their skin or in their hair.

A victim of a shooting is stretchered away by paramedics

A young victim looks on helplessly as her friend receives treatment

If the police find the perpetrators they will read them their rights and take them into custody, but it is not their job to investigate, only to identify who was at the location and to record the facts as they found them. Securing the scene also involves ensuring that the area has been thoroughly searched in case a suspect is hiding on, or near, the premises, posing a threat to the paramedics and the investigating unit.

THE NEXT STEP

Once the senior investigating officer is on site, he or she will begin by interviewing the officers who were first on the scene to get their initial impression of the location and the behaviour of those who were directly involved. He or she may find it necessary to request the assistance of more than one team if there are multiple sites; for example, in a murder enquiry the suspect's residence will require searching as well as the site where the body of the victim has been discovered. Each team is led by a crime scene controller who answers to a supervisor. The supervisor then reports to the investigating officer.

Usually the crime scene is a house, an apartment, commercial building or vehicle, all of which can be sealed off and examined in the minutest detail. And if a murder or violent attack has occurred in one area of a building, the whole property will be considered relevant to the case and will be scoured for clues. There may, for example, be evidence in the bathroom where the perpetrator has attempted to clean blood off their hands or tell-tale marks of forced entry at a window or door.

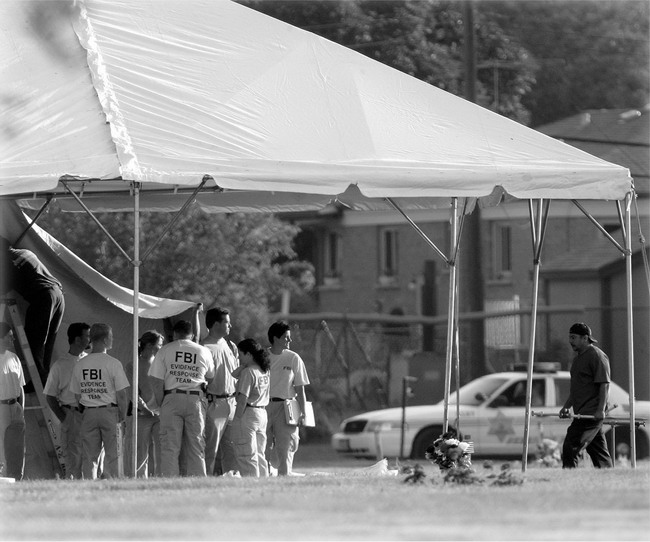

But if it is an exterior location police may have to extend the perimeter to include vehicle tyre tracks, footprints and areas where there is a chance of finding personal items, discarded cigarette butts, a weapon or trace evidence which might have been snagged on undergrowth. If it is a burial site for murder victims there could be other makeshift graves in the area, all of which will have to be excavated, photographed and combed for physical evidence. Exterior scenes may also have to be isolated by a tent to protect evidence from the effects of the weather and to exclude the prying eyes of curiosity-seekers and the media.

The FBI erect a tent to exhume a body in an attempt to gain more evidence

In the case of a terrorist atrocity involving an explosion the scene can extend for several miles and every inch of that area has to be sealed off and searched for the minutest fragments of the device in the hope that it can be pieced together again to give vital clues. In the rare cases where a wounded victim or perpetrator has staggered several miles, leaving blood traces around the neighbourhood, all of these drops will have to be photographed and catalogued.

The most challenging crimes to solve are those where the location of a discarded body is not the primary crime scene. Investigators then have to identify the victim (which could be made almost impossible if the body is incomplete or severely decomposed) and trace their last movements to the place where the death took place. One criminal profiler compared this scenario to finding the final page of a novel and then having to fill in the preceding chapters.

SEARCHING FOR CLUES

If a serious crime is committed in a busy street, investigators may have a limited time in which to gather their evidence. In such cases they may be forced to employ large search teams who will move in a line from one end of the street to the other to ensure they have covered every inch of ground. The same method will apply if there is a field or forest to be combed for evidence. Depending on their priorities, the seriousness of the crime and resources, the investigating officer may order a grid search which will require the search team to go over the same ground that they searched from right to left, but this time from top to bottom.

Any significant items that they come across will be indicated by a numbered marker and photographed so that a sketch or computer diagram can later be made of the area with all the significant clues flagged where they were found. Once an item has been bagged, labelled and logged it is impossible for someone to remove it or tamper with it. Fifty years ago evidence obtained by the police and FBI was rarely questioned, but considered among the facts in the case. Now, in our more cynical age where corruption among law enforcement officers is a possibility and the credibility of expert witnesses and forensic science is routinely questioned, it has become necessary to prove that the evidence is genuine and has not been compromised.

If it is a rural location it is routine procedure to take a sample of soil in case it can be matched to trace evidence on the suspect's shoes or clothing which could place them at the scene. Finally, the CSIs' own overalls are examined in case they have inadvertently picked up any residual material.

If the crime took place at the victim's own home or place of business then the investigation team can employ fewer officers and take as long as they need to make a thorough search. In the case of the pipe bomb murder of Chris Marquis, for example (see 'Mail Order Murder' here), investigators were able to return to the scene several times until they eventually found the vital clue they needed. By contrast, in the Ty Lathon drive-by shooting (see 'Driven To Murder' here), there were few clues at the scene. The killer had taken the most significant clue with him on the wheels of his car. The mineral deposits at the scene were found to be unique to the area and were subsequently matched to those found in mud caked to the wheel rims of his jeep. In another highly unusual case, a resourceful police officer had the foresight to ask the mother of an abductee to vacuum her living room and then he archived the dust so that many years later forensic scientists could identify its contents and match it to microscopic paint particles in the killer's car.

It is unfortunate that so much time and effort has to be spent on what often turn out to be fruitless searches for evidence, but nothing can be allowed to be overlooked. It can take just one piece of incriminating evidence to crack killers' airtight alibis and convince a jury that they are guilty, no matter how confident and convincing they may appear during their day in court.

Members of the San Diego County Search Team perform a grid search near where a body was found

Contrary to the picture of crime scene investigators presented in procedural police series, forensic investigators are not concerned with solving the crime. The job of a CSI is to gather and analyze physical evidence so that the detectives assigned to the case can put the various pieces of the puzzle together and determine who did what to whom, where, when and why. A CSI is dedicated to revealing the truth with the impartiality of a technician and it may be that the truth is that there is no crime to investigate. What was thought to be a suspicious death sometimes turns out to have been a suicide or tragic accident.

An apparent case of arson may have been caused by faulty wiring or carelessness, such as a discarded match or cigarette, while an explosion might have been triggered by a gas leak or a series of unforeseen and otherwise unconnected coincidences.

Sherlock Holmes, the master of deductive reasoning

Likewise, an apparent heart attack may be revealed to have been a poisoning, a drowning may be proven to have been deliberate and a tragic accident may be shown to have been an elaborate and callous attempt to defraud an insurance company. The only sure way of uncovering the truth in such circumstances is to maintain a clinical detachment from the evidence and let it tell its own story rather than trying to fit the evidence to a theory. This method of solving crime is known as deductive reasoning, the kind used by the most celebrated of fictional amateur sleuths Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple and many, many more.

But unlike Holmes and his fictional colleagues who were armed with little more than a magnifying glass and a chemistry set, today's crime scene investigators have a number of aids to determine the value of clues both in the laboratory and in the field.

A raging fire: deliberate or just carelessness?

CSI FIELD KIT

A typical CSI field kit would include the following:

• Protective suit to avoid contamination.

• Latex gloves. These serve two purposes: they ensure that the evidence does not become contaminated during transfer from the primary location to the lab and they also protect the crime scene personnel from the risk of biological contamination.

• Phenolphthalein. This chemical is used in the field as a presumptive test for blood to save time and lab resources. A cotton swab is moistened with one or two drops from a bottle of saline solution and then rolled against the stain to absorb the suspect substance. Phenolphthalein is added and, if it proves positive for blood, the cotton swab will change colour. The swab comes in a sealable plastic tube which ensures that when the cap is closed the sample cannot be contaminated.

• ALS (Alternate Light Source). This small pen-like torch is used to highlight faint fingerprints, biological fluid stains such as blood and semen and trace evidence including hairs and fibres. Its blue beam reflects back at a different wavelength than the light from a normal torch, requiring the attachment of a filter or goggles. In this sense it functions as a portable ultra-violet flashlight.

• Boots.

• Flashlight.

• Indelible ink marker pens.

• Measuring tape.

• Laser pens.

• Digital or 35mm film camera.

• Film.

• Tweezers.

• Evidence storage envelopes.

• Numbered plastic evidence markers.

• Flat rule markers for photographing significant items to scale, such as spent shell casings.

• Sketch pad.

• Blood drawing implements.

• DNA swabs.

• Evidence seals, tags, bags, and containers of varying sizes.

In addition CSIs will carry kits for lifting fingerprints and making casts of footprints and tyre tracks, plus a standard tool kit for removing items such as door handles, bullets from the walls of buildings and so forth. They may also consider it prudent to bring a metal detector, a special vacuum with filters for collecting trace evidence and anti-putrification masks to avoid the noxious fumes and risk of infection when attending badly decomposing bodies.

Although these kits are supplied by the laboratory, some technicians augment it with household and hardware items they find particularly useful. There are also special kits for collecting bodily fluids, bugs, dried blood, gun shot residue and various hazardous materials.

A basic fingerprinting kit will contain:

• Ink pad.

• Aluminium fingerprint powder.

• Dusting brushes.

• Clear lifting tape and acetate sheets.

• Aerosol reagent to highlight faint prints and bloodstains.

• Magnifying lens.

• Scissors.

• Tweezers.

• Scalpel. These are supplied with sterile disposal blades so that biological stains can be removed without the risk of contamination. A semen stain on a bed sheet, for example, would be cut out and brought back as a swatch of fabric, while a flake of paint might be scraped from a car bumper that had been involved in a collision, or a smear of dried blood might be scratched off and placed in an envelope or plastic bindle to be brought back to the lab for further analysis.

• Gel lifters, for lifting hand- or footprints from hard, flat surfaces. Their adhesive backing is rolled or pressed over the print which can then be taken back to the lab and scanned into a computer for comparison with others on a national database.

• Electro Static Dust Print Lifters are used to lift foot, hand, palm and fingerprints left in dust or powder. An electrostatic charge attracts the powder to a clear sheet of thin film without disrupting the pattern.

A tyre and footprint casting kit will include:

• Casting powder and compound.

• Frames.

• Rubber lifters.

• Fixative.

• Wax spray to enable castings to be taken from snow.

• Mixing bowl and stirring implements

A laser trajectory kit, which enables investigators to trace the source and direction of bullets, will include:

• A laser pointer.

• An angle finder.

• Penetration rods.

• A centring cone

• A tripod.

A sexual assault kit, also known as a rape kit, will comprise:

• Evidence envelopes for pubic hair and fingernail scrapings.

• Swabs.

• Smear slides.

• Blood collection tubes.

• Pubic hair combs.

• Evidence seals with biohazard labels.

• Sexual assault incident and authorization forms.

Chicago police use a ground penetrating radar device to check for the existence of buried bodies

ADDITIONAL EQUIPMENT

• Ground Penetrating Radar may look like an antiquated lawn mower but it is actually a very sophisticated and expensive piece of portable lab equipment which is rolled over an area of ground during the search for buried bodies. The signal penetrates the soil but bounces back when it strikes a solid object under the surface which will show up like an X-ray on the GPR's monitor.

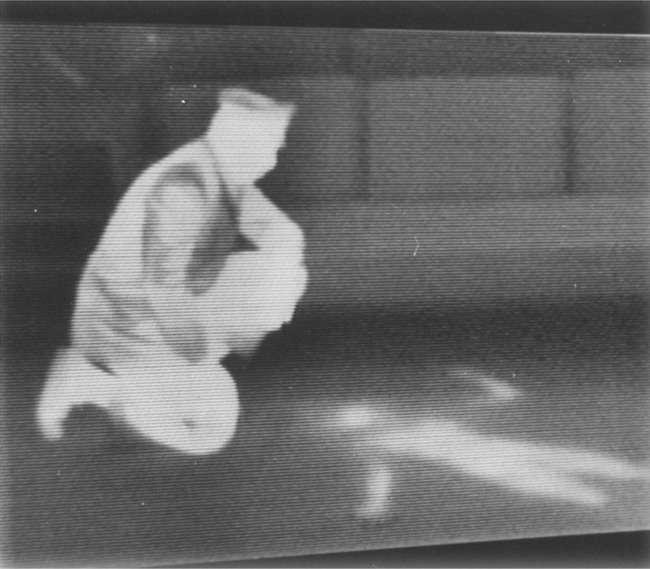

Thermogram showing infrared radiation from the body of a murder victim

• The Bullard Thermal Imager detects residual heat on surfaces such as soft furnishings so that the impression of a person who recently sat in a chair, for example, can be photographed for later enhancement back at the lab. Using a thermal imager means that it is possible to determine the distinguishing physical features or characteristics of a person who has recently been at a crime scene, such as the passenger in a car in which the driver might have been shot and robbed. On the thermogram the areas of greatest heat appear light, while areas of disruption are dark.

• The Drager Tube detects and identifies several hundred gases such as toxic fumes at a suspected illegal drug factory.

• A Live Scan is a portable digital fingerprinting scanner which makes prints instantly available for comparison using a national database and does away with the need for the traditional ink and paper method. It is ideal for forensic work as it can be moved easily from place to place.

Footprints in fresh snow: trace evidence has to be gathered quickly before the snow melts

Deborah A. Hewitt is a forensic science supervisor at the Montana Department of Justice and a former consultant for the FBI. The most common question she is asked these days is not, 'Who did it?', but 'How can I become a CSI?' Her experience is that each laboratory will have different minimum qualifications for their forensic-scientist posts. Normally a four-year degree in a natural science (chemistry, biology, biochemistry, geology or forensic science) is the minimum requirement, with emphasis on chemistry and biology, and possibly a Master's degree or a PhD to add weight.

It is Deborah's experience that forensic science is becoming more diverse and highly specialized. In the 1990s a criminalist, as they were then called, would go on site to gather any evidence they considered relevant and analyze it themselves back at the lab, but today the courts demand a greater degree of technical knowledge so it is common for CSIs to specialize in tool marks, teeth, tyres, footwear, fibres, fingerprints, gunshot residue, gasoline or guns.

The first stage in analyzing a crime scene is to establish a workspace outside the perimeter to minimize the risk of contamination of the scene and to save time travelling from the location to the lab and back again. Points of entry and exit need to be protected so that investigators can avoid walking through these areas and evidence gathering needs to be prioritized so that transitory trace evidence such as footprints in snow can be taken before they melt.

A DEDICATED INVESTIGATOR

Deborah's speciality is footprints and fingerprints. The science of fingerprint analysis is more complicated than you might imagine. Prints are created by a composite of organic components secreted by the person's own skin, mixed with anything else that they might have touched such as food grease, synthetic oils, paints, blood and so forth. Impressions have to be taken quickly; while prints made on smooth, hard surfaces can remain indefinitely if protected and undisturbed, those left on porous surfaces such as paper and wood can disappear quite rapidly because of the absorptive properties of the surface, although some have been retrieved from paper after 50 years.

When asked what sort of clues a CSI can derive from bloodstains, she will tell you that bloodstain-splatter analysis can provide a significant amount of information about a particular event depending on the patterns available and the condition of the scene and the evidence. Some facts that can be determined are the movement of the victim and suspect, the location of the blood source when a particular pattern was produced, the approximate number of blows sustained by a victim, the type of weapons used, the sequences of events, whether it is a primary or secondary scene, whether a victim has been moved after death and sometimes the time at which the crime took place.

Ask any CSI and they will tell you that the most difficult cases are not those that are traumatic, but those that are unsolved. Deborah admits that there is never enough money or manpower to handle all the criminal cases as fast as the investigators would like, but says that the most positive aspects of the job are being able to catch out a criminal in a lie and help to find justice for the victim. One might imagine that being a witness to the aftermath of so much violence could adversely affect the investigators, but they are given the opportunity to share their experiences during debriefing sessions and are routinely invited to private consultations with a counsellor.

There is more to forensic photography than simply pointing a camera at a dead body and clicking the shutter. The photographer's job is to record the scene as it appeared immediately after the crime was committed, with all the evidence in situ and undisturbed. It may be significant, for example, that a left-handed victim is found with their watch on their right hand as this would indicate that the body had been dressed after death, or that a male victim is found facing away from his murdered wife with his eyes and mouth sealed with masking tape as in the MacIvor murder case (see here). In that instance the photographs revealed that the wife and not the husband was the intended victim and that police should look for a sexual predator rather than a drug dealer as they had originally suspected.

Indonesian police take forensic photographs at the site of a blast in Jakarta, 2005

Although crime scenes are routinely videotaped if there has been a fatality, sharply focused still photographs are needed to document the scene, the surroundings and the position of relevant items for both the investigative team and those involved in any subsequent trial where photographs will be entered as evidence.

As such they are vitally important in confirming or refuting a witness's testimony, illustrate a point the defence or prosecution may want to make to the jury, or establish that a scene may have been staged by the perpetrator, as in a recent case where a discarded school book had been planted by the supposed abductee to put investigators off his trail.

THE PHOTOGRAPHER'S DUTIES

The photographer will begin by taking wide-angle shots of the exterior with close-ups of any signs of forced entry. Next comes a series of establishing shots of the interior showing the general layout before close-ups are taken of relevant areas and individual items in each room such as discarded clothing, weapons and the position of bodies.

All individual items are photographed with a measuring rule to show scale. An assistant will keep a detailed record, including the camera settings, of every single shot that is taken, in case there is a dispute or discrepancy of any kind. It is only when the photographer has finished his or her work that the bodies can be removed and the investigative team allowed in to look for evidence.

A forensic photographer has to be able to produce pictures of a consistently high quality as well as being able to adapt to difficult situations where there may be great pressure to work quickly, such as in a busy thoroughfare, or in a place where evidence is obscured by shadow. There is not going to be a second chance to photograph the scene once the rest of the team has been allowed to collect evidence.

Although digital cameras have obvious advantages over traditional 35mm film cameras, including the ability to enhance the image to draw out more detail, they are rarely used since images can too easily be manipulated.

The standard equipment is a 35mm single lens reflex camera, augmented by a tripod to guarantee rock-steady images when taking close-ups and a variety of filters and lenses for different situations. Filters and flash photography can create a 3D image to reveal the textured surface of tyre tracks and shoeprints or highlight bloodstains, fibres and gunshot residue.

Dr Jon J. Nordby, author of Dead Reckoning: The Art of Forensic Detection, is one of America's foremost forensic science consultants. A former medical investigator and philosophy student, Dr Nordby set up his own private company, Final Analysis, in the 1990s to offer forensic expertise and state-of-the-art laboratory facilities to overburdened and underfunded police departments on a freelance basis.

The key to criminalistics, he claims, is the ability to think clearly when faced with the daunting confusion of the average crime scene. That means relying on experience, intuition and abductive reasoning rather than text-book theories to identify what may be a clue and what can safely be disregarded. Abductive reasoning involves testing a likely scenario against the facts and only dropping it when one or more don't fit. It is the antithesis of the traditional method favoured by most detectives, which encourages the investigator to assume facts from clues left at the scene and then to build the puzzle piece by piece, groping in the dark until the final piece is in place.

A stopped watch gives vital clues to the dramatic sequence of events that have led to a person's death

Abductive reasoning requires the CSI to visualize what the puzzle might be from the outset and then to see how many clues fit that picture. This means the CSI needs to be able to recognize the significance of specific items rather than making assumptions based on a perpetrator's previous behaviour or that of his personality type. Nordby believes that his approach helps recognize when a crime scene has been staged and keeps guessing to a minimum. It puts the clues in context and in doing so re-creates the true chain of events.

This new approach could soon be adopted by more CSIs because all too frequently investigators are being misled by false clues deliberately left at the scene by criminals who are now acutely aware of the importance of forensics and the significance of certain types of trace evidence.

It is a popular myth that serious crimes are solved exclusively by detectives with the technical assistance of crime scene investigators and a pathologist who rarely emerges from the morgue. Although this team is the driving force behind many major investigations, there is a crucial member who is rarely credited with contributing to a case: the coroner (also known as the medical examiner). In Britain the coroner acts in a judicial capacity during the inquest to determine the cause of any suspicious or unexplained death and whether there is a criminal case to answer, but in America he or she has a more active role and frequently oversees the entire investigation.

Laura E. Santos, a deputy coroner with the Sacramento County Coroner's office, routinely attends the scenes of suspicious deaths. She interviews witnesses, researches the deceased's medical history, collates evidence and ultimately is the person who decides whether there is a case for detectives to investigate.

In California, coroners receive similar training to that of law-enforcement officers so that they are familiar with interview techniques and basic medical terminology and can interpret blood splatter patterns and other potentially significant clues as to the cause of death. They also need to have a basic understanding of anatomy and be up to date with common diseases and medications. However, despite impressions to the contrary, the vast majority of deaths investigated by the average coroner's office are from natural causes, with only 12 to 15 per cent attributable to suicide, accidents, drug overdoses and murder.

In 30 years Laura has learnt that each case is different and that the biggest danger is not a vengeful killer but complacency. Every death has to be treated with the same degree of inquisitiveness and a determination to uncover the facts. Even a natural death has to be examined if it was unexpected or if the individual had been suffering from a fatal illness and had not seen a doctor in recent weeks. In such cases the illness may be the result of poisoning, or even if was natural it may have been exacerbated by the wilful denial of medication, with or without the patient's consent. In cases of accidents there may be criminal charges to answer if the fatality was caused by another individual's negligence.

A case in point was the death of a 16-month-old child who had been declared dead on arrival in the emergency room of a local hospital from what appeared to have been natural causes. Despite the fact that the attending physician was satisfied there was nothing suspicious about the case, Laura insisted on treating it as an 'undetermined' death and ordered a routine autopsy. This revealed evidence of trauma and a homicide investigation was launched.

THE CORONER'S PROCEDURE

When Laura arrives at a location she has to determine whether the fatality is suspicious or not. Only then can it be declared a crime scene. The first thing she does is make a mental picture of the scene, securing an initial impression of the site and its surroundings, the position of the body and the behaviour of any witnesses, friends, family or neighbours which may prove relevant to her subsequent investigation.

While the CSIs collect and document any trace evidence, Laura will examine the body and make a preliminary assessment. An obvious sign of carbon-monoxide poisoning, for example, is unnaturally bright pink skin. Cardiac arrest produces a distinctive blue colouring of the upper chest and face known as cyanosis.

Laura will then examine the area around the body for prescription medicine and particularly empty bottles that may indicate suicide, assisted suicide or something more sinister. If there are what appear to be self-inflicted wounds, such as slashed wrists or gunshot wounds, is the situation consistent with what is known about the deceased? For example, if a gun is found in the victim's right hand and they are known to have been left-handed, there is the distinct possibility that it has been placed there by someone else.

An inventory of their personal possessions, including wallet, purse and credit cards, could point to robbery as a possible motive, although it is always possible that a scene may have been staged and the body posed to divert attention away from the real motive. An experienced coroner will be able to tell from just a cursory glance whether the scene is staged or not.

The next step is for the coroner to interview witnesses with particular attention paid to the person who claims to have discovered the body, as there is a possibility they might have been responsible for the death and be offering to assist the investigation so as to keep abreast of developments. Certain pathological types revel in being the centre of attention and being the key witness fulfils that role. If the witnesses are genuine they may provide important clues such as being able to confirm whether the doors and windows were locked. If not, the victim may have let the killer in, which suggests that they knew or trusted them – in which case they might be a family member, a neighbour or someone posing as an official such as an electricity meter reader.

Laura's most challenging case involved a female serial killer who was convicted of murdering seven of her lodgers and burying them in the back yard of her Sacramento home. The drug-dependent landlady was convicted on DNA evidence after detectives were asked to trace the whereabouts of an elderly vagrant who had apparently vanished without trace. Fingerprints were of little use in identifying the buried victims as the bodies had badly decomposed in the decade since their death and, being elderly, many did not have their own teeth, which would normally have been an infallible clue in putting a name to the remains.

So Laura researched the social security records of everyone who had received benefits while living at that residence during the past decade. Thirteen couldn't be accounted for, so she requested their X-rays from local hospitals and doctor's surgeries. A radiologist then made new X-rays of the bodies in positions which would match the borrowed X-rays from the patient's files so that any relevant fractures, deformities and distinctive features could be compared.

The whole process took nearly three months but meant that Laura was able to eliminate those who had died naturally or moved away. But not all cases can be solved and that is something that a coroner must learn to live with.

On another occasion Laura was called in to investigate the death of a teenager who had been found hanging in the back garden of his parents' house. His father had only been gone for a short while when the police were called in so it looked like a tragic accident, but by the time the parents began to voice doubts and suspicions it was too late for the coroner's office to pursue the matter as the forensic evidence had been compromised by handling and age.

Breaking the news of a loved one's death is another duty for the coroner and it is never an easy one, especially when it involves violence or the death of a child. She admits that it is often difficult to remain detatched from the more traumatic cases but she exercises and watches her diet to keep herself grounded. The average coroner's workload is not to be envied. Laura, for example, works four ten-hour days a week and is on call during all natural disasters and major accidents. But she admits that the work is never dull or routine and that she still gets a thrill out of riding in police motor launches and helicopters.

According to Laura the advent of DNA 'fingerprinting' has made identification of victims and suspects far easier and more reliable, but contrary to the impression given by TV crime series it is far from routine. Good old-fashioned fingerprints are still the most common method of identification, although it is only a matter of time before this too becomes computerized with all law enforcement offices having access to a national database such as the one featured on CSI.

The O. J. Simpson murder trial in 1995 was lost, as the prosecution would see it, through a combination of incompetence and carelessness on behalf of the Los Angeles police, who gave a textbook example of how not to process a crime scene.

The case against the former American football star and one-time TV actor was compelling. His ex-wife Nicole and her friend Ronald Goldman had been brutally murdered at her Brentwood home on the night of 12 June 1994, and there appeared to be indisputable physical evidence linking O. J. to the crime scene.

A bloodied glove found in the grounds appeared to match another recovered from O. J.'s house in Rockingham just five minutes' drive away, together with a sock which also had traces of Nicole's blood. Near the bodies detectives bagged a discarded hat which was later found to have hair and fibres which matched O. J.'s. And most compelling of all, there was a trail of bloody footprints leading away from the scene and bloodstains on the gate. The killer had evidently been wounded in the frenzied knife attack. When detectives called at O. J.'s home they noticed blood on a vehicle parked outside and a trail of blood from the car to the front door. Analysis proved that the blood on the glove found at O. J.'s home and the blood on the car were from three people, the two victims and O. J.

But O. J. couldn't be questioned. He had taken a flight to Chicago earlier that night and, when interviewed over the phone, appeared curiously uninterested in his ex-wife's death. On his return to LA the next day he was questioned by detectives, who commented on the fact that he had a bandage on his hand which he claimed was the result of having cut it accidentally on a glass in his hotel room.

He was allowed to remain at liberty for the next couple of days while the police concluded their examination of the crime scene, but on 15 June they lost patience with the star, who had gone into seclusion, and issued a warrant for his arrest. It was then that he attempted to evade capture during the now-famous slow-motion freeway chase which was televised live around the world.

It looked like the case against O. J. couldn't be lost. But it was.

O. J. Simpson looks at DNA 'autorads' showing the genetic markers of Simpson and the murder victims

O. J. hired a dream team of top-drawer defence attorneys who raised serious doubts as to the validity of the evidence, which they intimated might have been planted by over-eager or even racist detectives to frame their man. They even managed to secure a recording on which Detective Mark Fuhrman was heard to refer to Simpson as a 'nigger' no fewer than 41 times, which tainted the validity of his testimony and all the physical evidence he had accumulated. But the defence didn't have to work too hard. The police had undermined their own case.

On the night of the murder they had failed to secure the scene, allowing numerous personnel to trample through the bloody footprints and carry crucial trace evidence from room to room and out of the house on the soles of their shoes. Video footage of the police walk-through of the scene shows investigators working the scene without protective overalls or gloves and one policeman is actually seen to drop a swab then wipe it clean with his hands. During the trial Detective Philip Vannatrer proudly testified to the fact that old-school experienced officers of his generation did not wear protective clothing and evidently saw nothing wrong in handling evidence without gloves like a cop in a 1950s TV show.

The prosecution case was compromised still further by Vannatrer and his colleagues' insistence on going straight from the crime scene to O. J.'s home without changing their clothes or processing the evidence from the first location, which could have allowed transference of trace evidence from the crime scene to the second location.

And then there was the evidence which was captured on film by the police photographer, but which had not been logged in and could not be found in the archive. This included a bloody note seen in one particular shot near Nicole's head. It may have been irrelevant to the case, or it may have been crucial. We shall never know because it was presumably 'tidied away' with whatever else seemed like rubbish at the time and was lost. Incredibly, no photographs were taken inside the house, only of the immediate area where the bodies were found. So there is no record of any signs of a struggle or of any other relevant features or items that were later put back in their place.

More critically, the bodies of the victims were left as they lay for ten hours without being examined by a medical examiner, who would have been able to determine the time of death and recover vital trace evidence from the bodies. But after Nicole's body had been photographed someone had turned her over onto her back, eliminating the blood splatter that can be seen on her skin above her halter top in the official police photographs. It was the coroner's opinion that this splatter came from her assailant who had been injured in the attack, but no swabs were taken before she was turned. After she had been moved it was too late to do so. The coroner is also responsible for making a search of anything at the crime scene which might have a bearing on the cause and time of death. So a dish of melting ice cream in Nicole's house which the police ignored might have provided a vital clue as to the time of death, but no one considered it worth photographing.

Blood covers the path outside the home of Nicole Brown Simpson

As if this catalogue of blunders were not enough to seriously compromise the prosecution case, the police also failed to bag the hands of the deceased, they neglected to use a rape kit, and they did not examine or photograph the back gate, which was the likely exit point for the killer. It was only weeks later that blood was found there, prompting accusations that it had been planted, when in all likelihood it had simply been yet another crucial clue that had been overlooked. These incredible errors and omissions were compounded after Nicole's body was removed to the morgue.

Instead of being examined in detail, it was washed, thereby eliminating the last vestiges of trace evidence that might have given a clue to the identity of her killer. It was only two full days later that an autopsy was performed.

After a protracted nine-month trial O. J. was predictably found not guilty. The jury could have done nothing else, since the police errors cast more than 'reasonable doubt' on the proceedings. But in a subsequent civil case brought by the families of Nicole Simpson and Ronald Goldman the circumstantial evidence was deemed to be overwhelming. O. J. was found guilty and ordered to pay $33 million compensation to the bereaved families.

Demonstrating the fatal stab wound in court