CHAPTER 13

A Response to Olsen and Bernstein

Nicholas Eberstadt

MY THANKS to Jared and Henry for kicking off this discussion, and debate with such thoughtful observations and criticisms. I very much appreciate the kind words they offer for some of this research.

We three seem to be largely in agreement about the dimensions and contours of the “men without work” problem but disagree (at times acutely) about diagnoses of the problem and prescriptions for remedying it. So let’s focus on some of these contested areas.

Jared suggests the men-without-work problem is already well known. Maybe to a couple of dozen labor economists at think tanks and universities and to a similar number of business reporters and economics bloggers. Yet to more or less everyone else in the country, this is indeed, as I asserted in my subtitle, a largely “invisible” crisis—and “everyone else” includes most policymakers in Washington. If well-informed people really understood the magnitude of the male “flight from work” phenomenon, why would the “unemployment rate” still be the banner headline for virtually every story on each new monthly employment report? As I show in chapter 3, for every prime-age man who is out of a job and looking for one there are three others who are neither working nor looking for work.

Jared (and also Henry) strenuously object that my account places far too little weight on the role of “demand-side” factors (not least among these, the dramatic postwar decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs, partly or largely as a consequence of foreign trade competition) in creating America’s men-without-work problem. Please note, I do not contest at all the proposition that a lack of demand for male labor, and especially less-skilled male labor, is one of the factors responsible for today’s dire situation. I expressly agree with that proposition, and repeatedly, in chapter 7. My point rather is that demand factors are only one part of the dynamic: “supply” and “institutional” factors are the others. The real question here, then, is the relative importance of these respective factors.

I argue that institutional factors (i.e., the detachment from the labor force of many in America’s huge new army of male ex-prisoners and felons) is a significant and generally underappreciated component of today’s men-without-work problem (chapter 9), and I do not read Jared or Henry as contesting this. So the residual dispute must turn on the weight, within the overall postwar collapse of male work, of (1) a lack of jobs per se on the one hand and (2) a lack of motivation to engage in the competition for jobs on the other.

Men Without Work outlines five reasons that demand factors could well be less powerful in explaining the collapse of male work in modern America than many labor economists today assume (see chapter 7). Since I do not explicitly deal with the issue of manufacturing job decline—as Jared and Henry both fault me for and in retrospect I’d say quite correctly—let me add a sixth here: namely, there is some evidence of a relatively weak relationship between the decline in manufacturing jobs and the prime-age male flight from work for advanced Western countries as a whole over the postwar era.

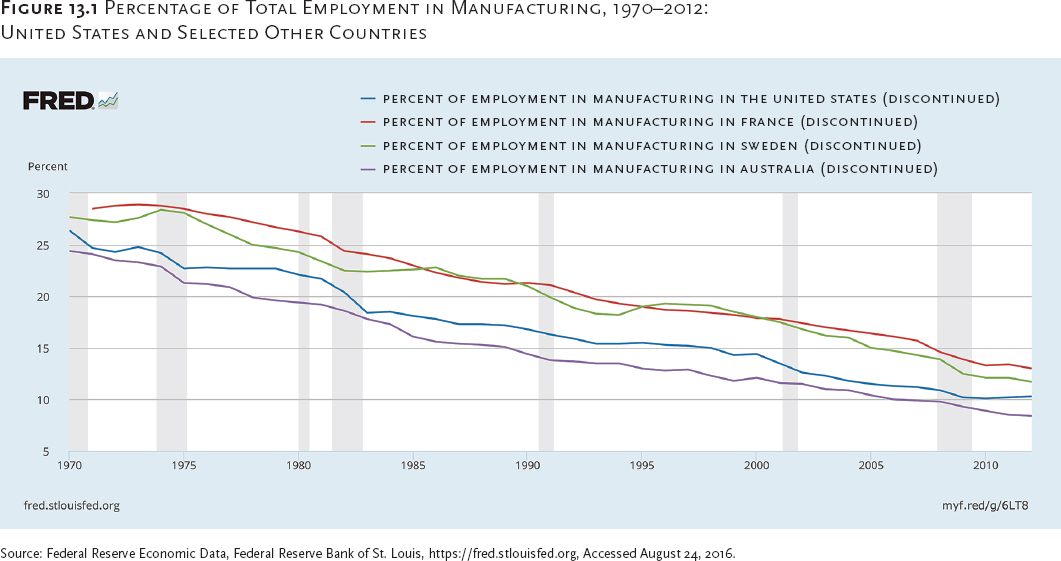

Figure 13.1 makes the case. Between 1970 and 2012, manufacturing jobs as a share of total employment in the United States dropped by about sixteen percentage points, to just over 10 percent. But that outcome was hardly unique: in France, for example, the drop was over fifteen points; in Sweden, sixteen points; in Australia sixteen points. France and Sweden follow closely the United States’ “de-industrial” trend line, and Australia now has a markedly lower share of employment in manufacturing than America—yet trends in labor force participation for prime-age men in the United States were uniquely disappointing when compared to other rich Western societies. Why this unwelcome “American exceptionalism”? Whatever the reason, it’s not because other advanced economies weren’t undergoing big structural transformations, too.

To highlight some disagreements over the role of welfare and disability programs: nowhere do I claim these caused the male flight from work. My argument instead is that they financed it—and in much larger measure than many researchers seem to appreciate. As I show in chapter 8, over half of prime-age men not in the labor force are themselves getting money from at least one government disability program nowadays, as are two-thirds of prime-age males not in the labor force (NILF) households. Making the case that most of the growth in Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) enrollment is explained by other demographic variables does not vitiate that finding—much less the fact that the share of prime-age men on SSDI has more than tripled over the past half century. Note incidentally that geographic mobility in America has fallen sharply over that same period, meaning, inter alia, that dependent men without work are less likely to move to higher-work states. Any dots to connect here?

As to policy recommendations: I was deliberately sparing of these for a number of reasons, not least because I did not want to propose an agenda I would have favored in advance, and for other reasons, under the guise of addressing the troubles identified in this study.

For job generation, my preferences favor revitalization of small business, while Jared’s may be for a public hand: I will grant him that his is the easier to effect by governmental decree. In regard to my call for disability reform: Is there really anyone left in Washington who doesn’t know the U.S. disability system is badly broken? My proposed “work first” principle for public aid for working-age men is channeling not Charles Dickens but rather contemporary Sweden, with its highly effective social policy changes over the past generation. I should have thought Jared would be sympathetic to those.

If we could succeed in reforming welfare for un-working single mothers twenty years ago, why not for un-working men today? Perhaps because the U.S. economy is weaker? A reasonable objection. But a key study on that earlier success concluded that macroeconomic conditions played only a relatively small role in getting women back in the labor force, with changes in incentives accomplishing most of that feat instead.1

TWO FINAL COMMENTS IN RESPONSE TO HENRY

First, his observation about the role of the draft in augmenting skills and training for young men in the early postwar era, while politically incorrect, may be very much on target. Remember, though, that the “selective service” was indeed selective—and as late as the Kennedy administration, one-third of the young men tested failed either physical or cognitive requirements for service. (That finding was ammunition, so to speak, for the Johnson administration’s “war on poverty.”) Thus, the most disadvantaged were also the least likely to avail themselves of such employment-enhancing experience as military conscription could provide.

And I am in violent agreement with Henry’s lament that available data can “tell us that a man is disconnected” from the labor force, but “tells us nothing about the mindset of the men who are disconnected.” Henry puts his finger on not only a failure of government information systems but a failure of empathy and understanding in our nation—perhaps a failure of mobility and solidarity as well. Would intellectuals and decision-makers in the early postwar era have been so obviously out of touch with “how the other half lives” as they are today? I have my doubts. Illuminating this human dimension of “America’s invisible crisis” should be imperative—not only for the instrumental reason of addressing a social ill, but for the moral one: we are a humane society, and this is exactly the sort of thing a humane society should want to know.