CHAPTER SIX

The Evidence

Education

For a long time, historians of education have recognized that basic education was much more broadly diffused in the antebellum Northern states than the Southern states.1 Although the scholars have not yet agreed upon the precise factor that explains this difference, one leading historian of education narrowed down the field of candidates to one factor, slavery.2

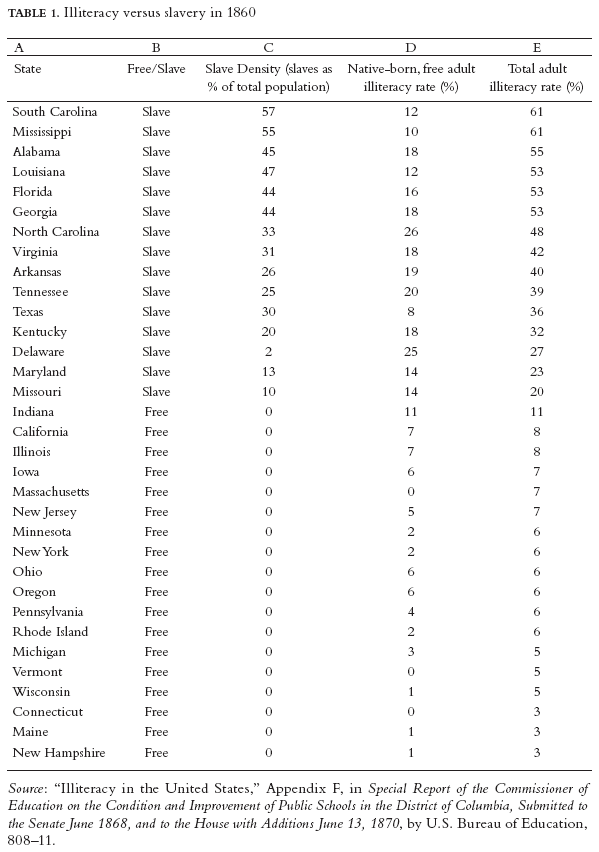

As table 1 demonstrates, illiteracy and slavery were strongly correlated in 1860. The illiteracy rate of native-born, free adults (column D) rose wherever slavery was present (C). This supports the claim of Republican Charles Van Wyck, that “your own people feel more keenly than we, that ‘The badge of the slave is the scorn of the free.’”3 Only one slave state, Texas (8 percent), had a lower illiteracy rate of native-born free adults than one free state, Indiana (11 percent), but many poor Southern whites had migrated to Indiana, which probably accounts for Indiana’s high illiteracy rate among Northern states.4 The table is sorted by total adult illiteracy (E), which combines the fractions of the total population who were adult slaves, and who are presumed illiterate, and native and foreign-born illiterate adults. This column illustrates Van Wyck’s other claim, that the slave states upheld “a system whose corner-stone is the ignorance of the people.”5

At one time, two leading Northern and Southern statesmen agreed upon the importance of basic education to republicanism. John Adams wrote that “education is more indispensable, and must be more general, under a free government than any other.” Since time immemorial, he wrote, despotisms of all kinds had made war against liberty, but if the principles of natural right were laid before the people, the light of understanding would spread and “the more disciples they will have.” Thomas Jefferson’s “Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge” noted that in the past, “those entrusted with power have, in time, and by slow operations, perverted it into tyranny; and it is believed that the most effectual means of preventing this would be, to illuminate, as far as practicable, the minds of the people at large.” A general education would also find and develop talent that nations had always neglected in favor of the well-born and the rich. Adams recognized that the laboring classes “are not always the meanest; there arise, in the course of human life, many among them of the most splendid geniuses, the most active and benevolent dispositions, and most undaunted bravery.” Likewise, Jefferson acknowledged those “talents which nature has sown as liberally among the poor as the rich . . . perish without use, if not sought for and cultivated.”6

Although they agreed on the principles of education policy, their sections differed in putting these principles into practice. In the early national period, education in the South was not so widespread as in the North. Traditionally, southern schools served a few families who would jointly pay the teacher’s fee. Sometimes, prestigious families would organize, endow, and supervise the schools, which then became permanent private academies.7 Northerners presumed that elementary education was a necessity, and the northern literacy rate, especially in New England, exceeded the South’s rate.8 The northern people also sensed that their communities were incomplete without a school. When northern populations grew at a distance from an existing school district, the distant people demanded a school district for themselves. A resident in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, recalled, “Whenever a neighborhood felt the need of a schoolhouse, one was erected at some point convenient to those who contributed towards its erection. The patrons selected trustees, whose duty it was to take charge of the school property and to select a teacher for the school.”9 Education was a community affair rather than a concern of a few families, as it was in the South.

But southern statesmen initially showed that they intended to implement republican principles of education and catch up to northern standards. Their states lacked the stronger cultural foundations of the northern people. To remedy this deficiency, Southern statesmen attempted to build general education from the top down. The delegates who framed North Carolina’s state constitution in 1776 included an educational provision requiring its legislature to establish schools and to make them available “at low prices.” The Georgia Constitution of 1777 similarly ordered that “schools shall be erected in each county, and supported at the general expense of the State.”10 Jefferson’s plan for Virginia provided for three levels of education, all funded by a county tax.11

Southern statesmen repeatedly echoed Adams and Jefferson, calling for popular education to strengthen republicanism and protect it from subversion. In 1803 Governor James Turner of North Carolina reminded the legislature that popular enlightenment is “the most certain way of handing down to our latest posterity, our free republican government,” because “education is the mortal enemy to arbitrary governments, and the surest basis of liberty and equal rights.” He asked for “the establishment of schools in every part of the State.” In 1811 Governor Benjamin Smith, also of North Carolina, warned, “In despotic governments, where the supreme power is in possession of a tyrant or divided among an hereditary aristocracy . . . the ignorance of the people is a security to their rulers.” Smith recommended that “a certain degree of education should be placed within the reach of every child of the State.”12 In 1811 Governor Henry Middleton of South Carolina recommended “the propriety of establishing free schools, in all those parts of the state where such institutions are wanted,” because “one of the first objects of a government, founded on popular rights, should be to diffuse the benefits of education as widely as possible.”13

All of these calls failed to achieve their intended aim. In 1779 Jefferson’s school plan came before the Virginia Legislature and was defeated. When the legislature finally enacted his plan in 1796, a change in wording permitted the wealthy to kill the plans in operation.14 The bill did not require but rather gave permission to the counties to fund and set up the schools themselves.15 Jefferson lamented that the county justices, who decided whether to implement the plan, were “generally of the more wealthy class” and “were unwilling to incur that burthen.”16 When their principles were put to the test, Virginia’s leaders chose to protect their wealth rather than to build up the republican character of their citizens.

In South Carolina, the people petitioned for free schools, and the legislature passed a school bill in 1811.17 But the new law deepened class division. School districts were created, and the district commissioners were required to prefer the poor for admission to the free schools, which thereafter became schools for the poor. To obtain state aid, families had to humiliate themselves and take a “pauper’s oath.”18 In addition, the law permitted the commissioners to give the public funds to private academies for the wealthy. The state had already created and funded South Carolina College in 1801. Rather than building a system of common school education, the law created separate and unequal systems of education for rich and poor, funded by the common treasury. These systems remained in place until after the Civil War.

Soon, Virginia emulated South Carolina. In 1818 the legislature passed over Jefferson’s plan again and instead created a pauper school fund and established and funded the University of Virginia.19 Jefferson disapproved of Virginia’s policy, lamenting the neglect of “primary schools” in 1820, and warning that Virginia was “fast sinking” and “becoming the Barbary of the Union.” The people had raised enough money, and “it should be employed . . . for their greatest good,” their general education. He asked, “Would it not have a good effect for the friends of this University to take the lead in proposing and effecting a practical scheme of elementary schools?” In Virginia as well, the pattern of education consisted in two separate and unequal systems until after the Civil War. In 1826 Governor John Tyler of Virginia held up the free school system of New York, asking the legislature to imitate that model, “embracing all, and alike available to all.”20 But Tyler was not reelected, and his bill did not pass. Instead, the legislature enacted a law providing for a “district free-school system” that authorized but did not require county commissioners to divide their counties into districts for the establishment of free schools, open to all free white children. Voluntary contributions had to fund the construction of schools. The commissioners could direct tax revenues to the support of these schools at their discretion. In practice the commissioners focused on the pauper schools instead.21

The legislature of North Carolina did nothing to establish free schools for decades, despite the requirement in their constitution, while the population of North Carolina sank into deeper illiteracy and ignorance. The Georgia Legislature also flouted its constitutional requirement and instead followed the example of South Carolina and Virginia. In 1821 the legislature set aside half of its school fund for paupers and the other half for private academies. Students could receive funding only by taking the pauper’s oath. In 1833 an anonymous author in the Southern Banner complained that Georgia’s educational system was “anti-republican in its tendency,” because “here as in an Aristocracy the poor are taxed for the benefit of the rich.” Public funds built Georgia’s “Colleges and Universities . . . but who reaps the benefit? The rich.”22

While the southern state governments strayed from their original mission and were funding pauper schools for the poor and academies and colleges for the rich, northern communities were making progress toward universal basic education. The proportion of children enrolled in elementary school was rising more quickly in the Northeast than elsewhere, particularly among female children. By 1830 most white Americans in the North had access to elementary education. Enrollment rates in the South were lower.23

The North sustained this progress whether the state governments supplied encouragements or mandates. In 1789 the Massachusetts Legislature passed a law, similar to its colonial law, requiring that towns maintain a school. But most towns already maintained a school and did offer a partially free elementary education. Responding to the complaint of the governor of New York, George Clinton, that a 1795 education law favored “the children of the opulent,” the legislature passed another law lavishing aid on local common school committees for five years. The law was not renewed, yet enrollments of pupils under twenty years old in New York increased from an estimated 37 percent to 60 percent from 1800 to 1825. Connecticut did provide generous financial support to local “school societies,” approximating a district system, and some American and foreign commentators regarded the common school system so funded the best in the country.24

Like the pauper schools in the South, urban charity schools in the North began as free schools for the poor. These schools transformed into common school systems, the forerunner of modern public school systems, serving all for free. At first, private benevolence and fear of city-dwelling youth growing into adult criminals motivated the establishment and funding of charity schools. In time, advocates for poor school funds advanced republican arguments.25 Boston’s city missionary Joseph Tuckerman believed that “if every child in our country, and in the world, between the ages of four and fourteen were in a school . . . and should receive as much instruction as could be given to them, it would be found that in the diversity God has made of human capacities . . . there is an ample provision for the whole number which is wanted for every service.”26 This was pure republican theory, reminiscent of Adams and Jefferson. The urban charity schools eventually attracted and admitted children from higher socioeconomic positions. The charity school systems of New York and Philadelphia first changed into common school systems. After 1820 urban common school systems grew and received public funds and oversight. They accomplished in the cities what the northern district schools had already been doing since before the Revolution.

After the 1830s the gap between northern and southern basic education steadily widened until the Civil War. In the North leading educational reformers Horace Mann in Massachusetts, Calvin Stowe in Ohio, Henry Barnard in Connecticut, and John Pierce in Michigan all urged reform, relying primarily on arguments to educate children for republican citizenship. All of them preached the power of education to elevate character and develop individual potential as far as the pupil’s talent could go, no matter how humble or unfortunate the child’s origins. All of them recognized that the opportunity to advance was the first fruit of republican society, and education was the surest prop of republicanism. All of them learned the gospel of education from personal experience in New England, where all were born and raised. Barnard came from a middling Connecticut family; the rest knew privation and were left fatherless as children, Mann at age thirteen, Stowe at six, Pierce at two.27 But all owed their success and social respectability to education. The common schools saved their lives, imbued in them a love of learning, and gave them a fair start in life. They worked hard, rose, and then became evangelists for common school education and by extension for American republicanism, to both of which they owed so much. Had not their New England forebears valued education and established schools, they would not have been in the position from which they could diffuse it further still, within their own New England and beyond.

The arguments of the reformers drew from the theory of the founders. In an 1837 report to the Ohio Legislature, Stowe’s central point was that “republicanism can be maintained only by universal intelligence and virtue among the people. . . . And do not patriotism and the necessity of self-preservation, call upon us to do more and better for the education of our whole people, than any despotic sovereign can do for his?” In his third report to the Michigan Legislature in 1838, Pierce wrote that “generally diffused education, combining the great powers of intelligence and a pure virtue, is the only safeguard of our public and our private rights; and upon the progress of this alone, depends the future permanence and character of all our republican institutions.” In 1871, as the first commissioner of the newly created U.S. Department of Education, Barnard wrote, “The problem to be solved under a republican government . . . is not the education of the few, or even the many, but of all.” Mann dilated on the dependence of republicanism on education more than any other of his compeers. In his Tenth Annual Report in 1846 as secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, Mann wrote, “Since the achievement of American independence, the universal and ever-repeated argument in favor of free schools has been, that the general intelligence which they are capable of diffusing . . . is indispensable to the continuance of a republican government.”28

The reformers aimed at programmatic public management over education, so that education would be more efficient, uniform, and consistent with national purposes. They favored the institution of state superintendents of public instruction, organization directed by the state government, and increased public expenditures. They pushed for a lengthened annual schooling period, higher wages for teachers, libraries, uniform textbooks, teacher training schools, education periodicals, and other reforms. All of these reforms aimed at diffusing the benefits of education by increasing the scale of schools, expanding student enrollments, and improving the quality of instruction under education officials’ supervision. Buoyed by the appeal of their arguments to their public, they did generally succeed at centralizing the oversight and funding of education at the state level in the free states. Although school enrollments in the free states were already rising when they began their reform work, enrollments further increased through 1860. However, the reform movement that they initiated barely affected the South.29

In the South new principles appeared in new arguments leveled against common school education. In 1830 Professor Thomas Cooper at South Carolina College published an attack on northern common school education plans in the Southern Review. “These schemes” were “neither just, nor expedient, nor practical.” Relying heavily on the remarks of John Randolph of Roanoke in the Virginia convention of 1829–30, he attacked majority rule. Taxation to fund common school education was “wanton plunder” and would inculcate “hatred among the persons of no property” toward those with property. Because “nature has made no two men equal in strength of body or strength of mind,” he concluded that the rich were rich because they were naturally superior. Adams and Jefferson also believed that some are more naturally talented than others, but Cooper assumed that natural superiority or inferiority is unalterably transmitted to children, not randomly diffused by nature. Cooper justified withholding education from the poor. Their education would make them a public nuisance. Finally, Cooper uncovered the nerve of his argument: “We deny that all men are created equal. We deny that any two men that ever lived were created equal in any one assignable circumstance. We deny that any human creature has any unalienable rights. We deny that there are any natural rights. . . . We assert that all rights, of whatever description, and without any exception, are the creatures of society, and of society alone.”30

Therefore, even if a poor child was born with superior talent, whoever controlled society had the right to assign him to an inferior place for life. This was not unjust, he maintained, because might determined right and justice. “Resist, if you have the force to justify resistance; if not, quit the country or submit.”31 Cooper sketched an oligarchic argument against republican education, and in a short time, the same argument spread among southern leaders in opposition to general education.

Principled respect for property rights and its corollary, principled commitment to limited government, do not explain southern reluctance to fund common schools, although they did sometimes claim this ground.32 Cooper’s argument does not rule out taxation and state activism per se but rules it out only on behalf of the inferior poor. In fact, southern state governments did tax all to fund the private academies and colleges for the benefit of rich children.

The one section of the country that supported education with the least government coercion and general taxation was New England, where local communities banded together, raised funds, hired teachers, and built schools. When general education succeeded at all in the antebellum South, the people took matters into their own hands, just as the people of New England had done, but the slaveholders used state power to thwart their efforts.

Slavery was sparse in Washington County, in the southwestern corner of Virginia. As the 1829 state law permitted, the people decided to pool their own efforts, tax themselves, and organize common schools, without state aid. By 1835 thirty-eight school districts operated. Educational development there and in the northern townships in the founding period were parallel, sharing the characteristic of fewer slaves, a stronger republican character, and a commitment to common schools.33 This success led to greater agitation in the 1840s and 1850s for a statewide system in Virginia. These efforts were defeated by “the interests of the academies and colleges of the State,” that is, the wealthy. They turned the aristocratic label back onto their opponents, ridiculing “the privileged class, the aristocracy of poverty,” who sought common schooling for all.34

In 1839 the North Carolina Legislature finally fulfilled its constitutional duty and enacted its first public school law. The law established county boards of education, which were required in order to divide the county into school districts, and the schools would be open to all. The law also required county courts to levy a tax to support the schools. The plan would apply only to each county that voted for it, and a majority of counties did. North Carolina, alone among the antebellum slave states, built for itself a common school system ex nihilo and became the first slave state to create the office of state superintendent of public instruction. These late but earnest steps were an exception to the rule, but it was too little, too late. Despite these efforts, North Carolina had the highest adult illiteracy rate in the nation but a public school attendance rate rivaling the free states by 1860.35

Education policy changed in North Carolina because the majority gained some power when the state constitution was altered in 1835. The low-slaveholding western section of the state demanded common schools, while the rich in the high-slaveholding eastern section usually opposed them, a pattern repeated all over the slave South. The North Carolina constitutional convention of 1835 retained the eastern legislators’ disproportionate representation, but weakened their strength. In addition, the amended constitution changed the electors of governor from the members of the legislature to the people. These changes and the growth of western North Carolina’s white population sufficiently tipped the scales on the common school question to the side favored by the western part of the state.36 The North Carolina convention of 1835 directly led to the enactment of the 1839 education law, showing that the establishment of common schools in the South required the marginal increase in popular influence in state government.

The same factor determined the fate of common schools in antebellum Louisiana. Since Louisiana had been a territory, private academies flourished, supported by government’s largesse. The parishes that distributed state aid had to reserve limited school enrollments for those designated poor.37 Louisiana, too, had created the distinction between the poor and the rich in their educational laws. But common folk had emigrated to the northern part of the state in large numbers in the 1830s and 1840s, creating a new bulge of political power in that low-slaveholding section, counterbalancing the power of the rich who resided in the high-slaveholding section.38 At the state convention of 1844, preceding the new state constitution of 1845, the secretary of the education committee reported the same complaints heard all over the slave states.39 Publicly funded teachers were incompetent and negligent. Enrollments were down. Only the wealthy were enjoying a good education. School funds earmarked for the poor stigmatized the recipients and repelled many citizens. Large state expenditures for colleges and academies benefited only the rich, because without the availability of basic education, the majority were not qualified to attend them.

The 1845 constitution included an educational provision for the first time, providing for a state superintendent of public instruction, a public school fund, and free schools supported by taxation. The reforms aimed at replacing the stigmatizing poor school system with a competent public school system for all. The constitution also eliminated property qualifications for voting, which enfranchised the new mass of common folk in the northern section. Louisiana commenced building a free school system on the model of northern states.40

The slaveholders soon struck back. In 1852 a new state constitution apportioned representation in the legislature by enumerating total persons, slaves included. By this provision, they gained firm control of the state.41 That same year, the legislature abolished the office of parish superintendent, cut the state superintendent’s salary, and relieved the superintendent from visiting the parishes, with the result that the numbers of operating schools and enrollments precipitously dropped.42 The changes “seriously crippled” the embryonic free school system.43 The movement away from the establishment of common schools corresponded with the increase in power of the high-slaveholding section of Louisiana, secured by the constitution of 1852.

South Carolina’s school policy remained intact from 1811 until the Civil War. As in other slave states, the partisans who fought over educational policy were organized and arrayed along intersectional lines within the state, dividing the slaveholders from the poorer citizens. The low-slaveholding upcountry, the northwestern section around Greensville and Spartanburg, agitated for an improved popular educational system. But because the high-slaveholding low country enjoyed disproportionate representation, the legislature resisted calls for common schools, sometimes with open hostility. As a result, the white majority never had access to respectable education. The teachers at poor schools, at one point, were generally adjudged as being “unqualified for their stations.”44 The county school commissioners often neglected their oversight of the schools. Illiteracy was widespread.

The example of antebellum South Carolina proves that the state’s abstention from establishing a publicly funded common school system cannot be attributed to state leaders’ fidelity to limited government and principled opposition to taxes. In fact, their conduct reveals that their claimed fidelity to local liberty, limited government, and property rights in national councils was inconsistent with their practice in their state. Their inconsistency suggests that their positions advanced in national councils were unprincipled and were invoked for political expediency. The state government deliberately pursued an educational policy adverse to the people and favorable to the wealthy. Funds for the pauper schools were divided according to the same formula by which the low-country slaveholders dominated the legislature, that is, the funds were malapportioned. Hence, in a given year in the 1840s, the poorer low-slaveholding Spartanburg district received fifteen hundred dollars of the school funds, while the wealthier, high-slaveholding St. Phillip’s and St. Michael’s parishes received fifty-one hundred dollars in funds, despite the higher number of voters in Spartanburg than in the other parishes.45 The state government actively appropriated more public funds for those who needed less and appropriated less state funds for those who needed more.

Also, the state government actively prevented the poorer sections of the state from helping themselves. In 1855 state senator Thomas Patterson Brockman appealed to his colleagues to pass a law allowing the people in the free school districts to tax themselves as each district might or might not wish and to use the funds to establish common schools.46 A “great many” of his constituents from low-slaveholding Greenville abstained from taking state funds, he said, because they refused to be regarded as paupers. But he had ascertained from his constituents that, although their means were modest, the people would accept a capitation tax for the purpose of establishing a common school system. They would attend the schools if they knew that their own funds, and not funds appropriated for paupers, provided the support. This would remove the pauper stigma from the free schools. These funds, combined with the funds appropriated by the legislature to the district school commissioners, would provide enough resources to support the broader diffusion of elementary education.

In the lower branch of the legislature, two representatives from Greenville and Spartanburg supported legislation with a similar funding provision along with a provision for the establishment of a state superintendent of public instruction. One representative supported the capitation tax, “in confident expectation that the day will arrive when my children, your children, and the children of us all, will be educated out of the common treasury.” These bills failed. One of the arguments in the opposition was that the tax power belonged to the state legislature, and, therefore, the local people did not have the right to tax themselves even if they chose to do so.47 The poorer, low-slaveholding people in the upcountry desired to pool their small resources and establish a common school system themselves, as the western Virginians and early northern townships did. But a majority of the state legislature, rather than leaving them alone and letting them do what they wished, actively blocked local self-government. The South Carolina doctrine of local self-government, loudly proclaimed by the state against the national government in national councils, did not apply to a parallel case, a section within South Carolina asserting local self-government against the state government in state councils.

Barnard and Mann actively assisted the development of common school systems in the antebellum South and corresponded with their founders and leaders, who were often naturalized foreign educators or transplanted northerners.48 Predictably, their efforts attracted attention from southern opponents who tellingly argued that state funds were for free schools for the poor, not common schools for all. Some objected to the common school ideal on principle, because it was hostile to their idea of good government.49 In 1852 one southern writer rejected mixing the rich and poor in common schools. He endorsed the opposite idea that students and instruction should be segregated, not by the students’ ability, but rather “in accordance with the circumstances under which he is to commence his career in life.” This is the idea of Thomas Cooper in action. The writer agreed with “objections to sending their children to schools which are open to all indiscriminately.” Furthermore, republican theory was wrong. Education was not “the palladium of our liberties,” nor “the guide which is to lead us to eternal truth. We believe in neither of these dogmas.” The many must work with their muscles; “the privileged few must govern.” Education was for the latter but, if received by the many, “exposes them to the danger of attacks from the demagogue.” Education for the poor was stirring up agrarianism and was “only a new element of evil. There is no necessary connection between learning and freedom.”50

The republican logic of common schools clashed with oligarchic government and would lead some principled defenders of oligarchy to rise viscerally to the defense of their political regime, once they discerned what northern educators like Barnard and Mann were doing in their section of the nation. In New Orleans, New England teachers were called “mischievous spies and agents,” which, in a sense, they were.51 Sectionalism in education arose from a sharp difference in political principles, and this explains why southerners expurgated Yankee teachers, textbooks, and educational ideas.52 Northern “philanthropy” threatened the southern way of life. Evidence suggests that southerners with republican views on education knew that they ran the risk of punishment at the hands of the oligarchy. In one pathetic letter to Mann in 1839, a Mississippian ardently pleaded with him to send him educational materials, adding in a postscript, “Please Sir, not to make this communication public.”53 His correspondence indicates that he was not living in a republican political society in which the people ruled and the rights of conscience were protected. Indeed, he feared reprisals from those who were determined to keep the people in ignorance.

Mann had explained that while republics depend on enlightened citizenry and free schools, “a sincere monarchist, or a defender of arbitrary power, or a believer in the divine right of kings, would oppose free schools for the identical reasons we offer in their behalf.” It was reasonable that in political regimes in which the people were not sovereign, the educational policy of the rulers would be that free schools “should be immediately exterminated.”54 This was the real reason common schools failed in the South.

After he was elected to the House of Representatives, Mann brought these reflections and experience to the floor in 1848. He attacked “the oligarchy who rule the south.” Among the effects of slavery, he called attention to educational culture. The oligarchy kept the slave in ignorance because education would teach “his natural rights.” Therefore, slave education “is prohibited by statute, under terrible penalties.” Likewise, the oligarchy suppressed education of the white majority. The rulers needed ruled whites to remain ignorant and, therefore, weak. The cultivation of ignorance among slaves and the white majority preserved the slaveholders’ mastery over political society. Mann identified the source of the stereotypes of ignorant white southern “rednecks” and former slaves.55 The oligarchy deliberately neglected their natural talent, by design, for political necessity.

Mann reached into his education statistics to reveal the extent of illiteracy in Kentucky, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, sarcastically referring to Virginia’s “republican Government supported by the two pillars of slavery and ignorance!” He claimed to have extensively corresponded with “the intelligent friends of education in the slave States” for the prior ten years, but they could not make headway, because it was “impossible for free, thorough, universal education, to coexist with slavery. . . . Slavery would abolish education if it should invade a free State; education would abolish slavery if it could invade a slave State.”56

More precisely, the slaveholders, and not slavery, sought to “abolish education.” But these slaveholders, “the oligarchy who rule the South,” had not abolished education for their ruling class. “In one thing the South has excelled,” Mann conceded: “training statesmen.” The oligarchs hoarded education for themselves, funded by the common treasury, and withheld its blessings from others. Free states and slave states presented a contrast of opposites, republican versus oligarchical: “The free schools of the North lead to the common diffusion of knowledge and the equalization of society. The private schools of the South divide men into patricians and plebeians; so that, in the latter, a nuisance grows out of education itself.” Southern hostility to popular education followed the logic of oligarchy.

In 1859 Senator James Mason of Virginia verified the general point in Mann’s speech. If Congress were to authorize the proceeds from public land sales to fund education, “Would it not be in the power of a majority in Congress to fasten upon the southern States that peculiar system of free schools in the New England States which I believe would tend . . . to destroy that peculiar character which . . . belongs to the great mass of the southern people?”57

Common schools would destroy the “peculiar character,” that is, ignorance, of the “great mass,” which was essential to oligarchy. The wayward grandson of the great Virginia republican George Mason understood that a republican education and the political character of the South, which his ruling class dominated, were incompatible. After the war, fellow Virginian and early historian of education Charles Dabney diagnosed the same cause: “An aristocratic organization of society” had blocked the establishment “of public schools, properly speaking, until the civil war had destroyed her old institutions and so prepared the way.”58

Many other southern educators corroborated Dabney’s conclusion, not long after the end of Reconstruction. At a meeting of the National Education Association’s Department of Superintendence in 1879, Georgia state school commissioner Gustavus Orr presented a paper that began by acknowledging the antebellum South and the postbellum South were “two civilizations” and “distinct.” The educational history of his own Georgia, he said, mirrored the rest of the antebellum South. Antebellum Georgia generously aided the education of the rich, especially after 1835. Georgia’s four institutions of higher education, the University of Georgia, Oglethorpe University, Mercer University, and Emory College, produced fifty-five hundred alumni, “who have filled with honor high places in all the departments—legislative, executive, and judicial—of the national and of their respective State governments,” as well as distinguished men in law, medicine, theology, science, literature, and education. The private county academies educated men and women “with respectable academic attainments.”59 These academies sometimes received aid from the state but operated on private tuition.

But on the subject of elementary education, the “inferior schools,” Orr admitted that the teachers of elementary institutions “were often incompetent.” No level of his state’s governments offered teaching institutes, associations, libraries, periodicals, examinations or licenses, or supervision. The teachers answered only to the patrons, who “were often utterly incompetent to judge the teacher’s qualifications.” The state government “did not propose to make even these inferior schools free.” Funds were provided for “the education of the poor.” Orr admitted that in the antebellum South, “our inferior schools were indeed very inferior” and “far behind” the northern states.60

Orr proposed the political axiom that “education by the State rests upon the sole basis of self-protection.” What kind of state is protected by an educational policy that provides for private academies and institutions of higher education but withholds or absolutely forbids elementary education from the majority? His answer was clear that the southern state governments had placed a premium on the education of the few and on perpetuating the ignorance of the many. But “minds of thinking men” in the new postbellum southern civilization were changing.61 They were beginning to accept the necessity of education’s “greater universality.” The change portended a change in southern civilization, from oligarchic to republican.

In his address to the Southern Education Association in 1899, Alabama state superintendent John Abercrombie used the terms old South and new South to distinguish the antebellum and postbellum South. The old South was “of aristocracy and bondage.” Though claiming only one-third of the nation’s population in 1861, “the South excelled the North in the number of colleges and college professors; equaled her in the number of students enrolled in academies and colleges and universities, and approximated her in the amount of money expended for higher education.” State aid “in whole or in part” supported these colleges and universities. In turn, they produced graduates “who have not been excelled” in “science, art, literature, education, and statesmanship.” But the South neglected schools for industrial training, because the “old South did not awaken to a realization of the truth that industrial trades are as respectable as business and professional callings.” That is, the old South believed in a different truth, that the industrial trades were not respectable. Similarly, in “the matter of common school education the old South did not keep pace with the North.” But in the postbellum South, Abercrombie favored a new approach to education—at least new to the South—that he connected to the maintenance of free government: “We fully realize that, in a government like ours, the preservation of free institutions depends upon the general intelligence of its citizens.” Whereas government in the old South preferred to educate the few, and prevented general education, “universal education at governmental expense is now a well-established Southern doctrine.”62

At the Ninth Conference for Education in the South, convened in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1906, Governor Joseph W. Folk of Missouri urged the conference audience to pay “more attention to the education of the many instead of devoting nearly all our energies to the education of the few.” Noting the generous allotments of public funds to universities, he said, “It is more important that all of the people have some education than that some of the people have all of the education.” Whereas in “foreign lands ruled by Kings and Emperors” only a single child needs an education “with special reference to the duties of sovereignty,” in the United States, “every child will be a sovereign,” and so attention must be paid “to instilling into the minds and hearts of the youth of the land the sacred duties of sovereignty in a free country where every man is a King.” Another speaker at that conference, Alabama state superintendent Isaac W. Hill, announced, “It was not until 1898 that public schools began to attract much attention in Alabama.”63

Writing for the Association of Collegiate Alumnae in 1900, a daughter of the South, Celestia Parrish, recalled that before the war, “Massachusetts and Connecticut were making education possible to every boy at least,” and in the southern states, the “poorer classes in the meantime were not educated at all.” To Parrish, their policy that disregarded the southern majority derived from the same principles that justified oligarchy. Noting that the poor usually could not read nor write, she asked in the voice of the slave master, “Why should they? Had not God ordained that some men should serve others?” Education in the South thrived only among “the upper classes,” who sometimes employed “tutors of the traditional type for the education of their boys, and were sending their sons back to Oxford and Cambridge for the higher training.” In the South, education “was distinctly aristocratic” and “developed a splendid superior class.” In her present time, Parrish noted the ongoing but incomplete establishment of southern public schools. She stood for universal elementary and high school education as necessary for citizenship. Yet in her day, as in the past, “A few wealthy people are still unwilling that their money should be taken to educate their neighbor’s children.” This conduct, she said, was “impossible to understand” without “recalling some of the conditions of the past.” She attributed the origin of those conditions to the aristocracy.64

The South did not begin that way. When the United States became a nation, leading Americans in the North and the South advanced arguments and framed laws calculated to secure a general education for free Americans. Over time, the free states did diffuse education more widely among the people. In the slave states, government policy departed from the educational aims of the founders and supported oligarchy.

Property

The founders’ republican theory of property began with natural equality. John Adams wrote that “through life,” he had “asserted the moral equality of all mankind,” attributable to “God and nature.” All have a right to liberty “derived from our Maker.” Also, “Property is surely a right of mankind as really as liberty.” He added, “If ‘Thou shalt not covet,’ and ‘Thou shalt not steal,’ were not commandments of Heaven, they must be made inviolable precepts in every society, before it can be civilized or made free.” Civil equality derives from natural equality, so that “each individual of the society has a right to be protected by it in the enjoyment of his life, liberty, and property.”65

With Aristotle, Adams recognized that human beings are a compound of equality and inequality. He observed that “nature . . . has ordained that . . . no two creatures [shall be] perfectly equal. . . . [Nor can two creatures ever] be made so by any power less than that which created them.” Individuals are born with unequal abilities. “There are great inequalities” among mankind, including natural talent, and the “sources of inequality, which are common to every people . . . can never be altered . . . because they are founded in the constitution of nature.”66 Each member of the human family is endowed with an equal share of liberty but an unequal share of ability, by which mankind acquires unequal property. Just laws are equal laws that recognize this paradoxical constitution of human nature and equally protect what is equal and unequal in mankind.

James Madison concurred with Adams. Every human being has a right, “in exclusion of every other individual,” to the “liberty of his person” as well as to “the free use of his faculties and free choice of the objects on which to employ them.” A government is “just government, which impartially secures to every man, whatever is his own.” Madison also recognized that human nature is a compound of equality and inequality. None is naturally endowed with more or less liberty, but all are more and less naturally endowed with ability, and “a distinction of property results from that very protection which a free Government gives to unequal faculties of acquiring.” Things can go wrong when “an excess of power prevails,” such that those with more property control the government and rob the poorer citizens of their liberty and property, or when poorer citizens become strong, control the government, and rob the richer citizens of their liberty and property.67 This is unjust government. Just government favors neither the rich nor the poor, but equally protects equal liberty and unequal ability.

Nevertheless, widespread poverty endangers just government. Following Harrington, Adams believed that the rule “power always follows property” is an “infallible . . . maxim in politics.” Under the conditions of extreme inequality in property, just laws are practically impossible to uphold. Approvingly quoting Aristotle, Adams showed that neither liberty nor property, and sometimes not even life, is safe. Both the rich and the poor “with difficulty obey reason,” due to the “excesses” unique to each. The rich “are not willing to submit to command or law,” and they do not know “how to rule over freemen, or to command others, but despotically.” Deprivation “makes the poor too mean,” and they “are in the habit of being commanded, too often as slaves.” In cities like this, “one party despise, and the other hate,” and “the government must either be in the hands of the meanest rabble, or else a pure oligarchy.” Wealth determines rank; hostility, distrust, and tension among the ranked parts of society are constant; a state of war within political society prevails. Genuine friendship is difficult; what is left of friendship is akin to war comradeship within the ranked part of society in which one is a member. The parts of political society become insular; hostility and violence to outsiders are acceptable; unquestioned loyalty to one’s rank is expected. Sometimes broils and open warfare break out between the few and the many, the former unjustly seeking complete domination, the latter unjustly seeking theft. These, Adams wrote, were among “the wisest sentiments of Aristotle.”68

Adams saw many instructive illustrations of this problem in histories of Europe, especially the chronic contest between patricians and plebeians in the Roman Republic. He observed, “The patricians usurped the lands, and the plebeians demanded agrarian laws.” The conflict destroyed their sense of justice, and they massacred each other. When the civil wars ended, everyone in Rome lost their liberty. Therefore, it is “essential” to consider how to address inequalities “in the institution of a government.” The people will tolerate an inequality of property and will uphold natural justice if most can avoid poverty. Adams mentioned in his diary that in his career, he kept company with many “very rich men,” yet “there is not one of all these who derives more pleasure from his property than I do from mine; my little farm, and stock, and cash afford me as much satisfaction.” Inequality is tolerable if most have modest wealth. The condition to be sought “is to make the acquisition of land easy to every member of society,” that is, make upward economic mobility possible. If this is achieved, and “the multitude is possessed of the balance of real estate, the multitude will have the balance of power, and in that case the multitude will take care of the liberty, virtue, and interest of the multitude, in all acts of government.”69

Adams believed that from the earliest settlement of New England, the people “felt, if not understood,” these organizing principles of their society with respect to property. Although they held their lands in the name of the king, they were unwilling “to render homage . . . [to] subordinate lords,” and they “transmitted to their posterity a very general contempt and detestation” of paying rents in acknowledgment of feudal superiors. Massachusetts entirely lacked “artificial inequalities of condition, such as hereditary dignities, titles, magistracies, or legal distinctions,” so that “moral and political equality” overcame the legacy of the Old World.70

The economic history of colonial New England lines up well to his account. The New England settlers recognized that the equal right to accumulate property was God-given and that the protection of God’s unequal bestowal of talent for acquiring property was a more just basis for accumulating property than artificial titles and privileges. Work earned title to property.71 Subsequently, New England successfully resisted attempts to impose feudal land titles in the seventeenth century and moved toward fee-simple land titles before the mother country did.72 Between 1620 and 1630, New England began land privatization, with the result that property ownership equalized, despite attempts by government to preserve unequal holdings. As government further established property rights, agricultural commerce flourished, so that landowning families conducted most production and consumption. The availability of land and the growth of commerce drove up wages, to the point that in Massachusetts, “it was difficult to distinguish gentlefolk from servants.” By the end of the 1640s, New England had begun to develop a diversified economy. By the mid-1700s, per capita income in New England was lower or equal to that to that of the southern states, depending upon the metric used, but far more evenly distributed.73

The New England communities transformed the feudal institutions of property. The smaller proprietors or tenants refused to accord honors to the larger landowner that feudalism otherwise entailed, and the large landowner could no longer command his neighbors in consequence of greater wealth.74 Power slipped from the hands of the rich. Political equality became firm, despite economic inequality; economic rank no longer determined political or social rank; republicanism overcame feudalism. Before national independence, the economic condition of New England already supported republicanism.

Virginia entered the Union in a much more unequal economic condition, and after national independence the attempt was made to equalize property ownership. Thomas Jefferson led Virginia’s “first republican legislature which met in 76” to adapt the state’s laws to a “republican form of government.” Jefferson, like Adams, believed in the prudence of measures “lessening the inequality of property,” which would ensure “the equality among our citizens so essential to the maintenance of republican government.” The laws of entail and primogeniture, Jefferson said, had raised up “an aristocracy of wealth, of more harm and danger, than benefit, to society,” and had obstructed the rise of an “aristocracy of virtue and talent, which nature has wisely provided for the direction of the interests of society, & scattered with equal hand through all it’s conditions.” The abolition of these laws “was deemed essential to a well ordered republic.” He succeeded at this reform, but the effect of the legislation was minimal.75 Although the laws did break up the landed estates, only the dispossessed progeny of the rich felt its benefit.76 The reform helped level inequality in landownership at the top of the economic scale, but did not affect the many Virginians at the bottom of the scale. Jefferson’s draft constitution for Virginia in 1776 included a further remedy, a provision to grant public lands to the landless in lots of fifty acres, but the provision never became law or part of the Constitution.77 Instead, property inequality continued to plague Virginia, and the prime suspect for causing this was slavery.

The evidence indicates that the elasticity of property inequality in the South always related to density in slaves. Where slaveholding was low or nonexistent, landownership was diffused more equally, as in New England. Where slavery was most dense, property inequality widened.78 According to the census of 1860, the modal size, or most common size, of a farm was in the range of 20 to 99 acres in 94 percent of all counties in the free states, but the modal farm size exceeded 1,000 acres in 26 percent of all counties in the slave states. The eight states with the highest number of counties with modal farm size of 100 acres or above were slave states. Ten of the eleven states that had no counties with a modal farm size of 100 acres or more were free states. New York, with a total population of 3.9 million free persons, had 246 farms that were 500 acres or larger, while Florida, with a population of 140,424, of whom 44 percent were slaves, had 288 farms 500 acres or larger.79

In Virginia in the 1780s, one scholar estimated that “from one half to three fourths of the adult males, exclusive of town dwellers, were landless. . . . Most of these landless men were very poor. Seven out of ten owned no slaves, and half had not even a cow.” They were either laborers or tenants who paid rent in order to farm the property of large landowners. The highest percentage of landless men, 75 percent, was found in the Northern Neck region, where slavery was the most dense. There, large estates predominated, but only two-fifths of all households owned any land. While a great many were poor in Virginia, a very few were land wealthy. One out of 25 men owned 500 acres and 20 slaves. Where slave density decreased, property inequality diminished. In the southwestern part of the state where slaves were few, there were more middle-size farms and few large estates, and only 10 percent of the men had no property. The proportion of the landless and very wealthy to total population was lower there than in any other region of the state.80 But in the ten counties in Virginia and six counties in Maryland that composed the Tidewater region, “just one in four landowners . . . had fewer than 100 acres.”81

Wealth distribution in South Carolina had been fairly equal until 1710.82 As a wave of new planters settled in the low country, slavery increased. The total population of the low country by 1770 was 88,244, of which approximately 22 percent was white and 78 percent black. In the backcountry, the ratios were the reverse. Of an estimated population of 36,000, 83 percent were white and 17 percent black. The increase in slave density in the low country correlated to growing wealth concentration. Between 1720 and the 1770s, the distribution of all slaves who worked on South Carolina plantations with more than 30 slaves increased from 29 to 64 percent. In one low-country parish in 1763, 39 percent of landowners possessed fewer than 500 acres of land, while 38 percent possessed more than 1,000 acres of land. By 1793 landowners possessing fewer than 500 acres dropped to 23 percent, and landowners possessing more than 1,000 acres of land increased to 49 percent. By the early 1800s, the average size of a low-country plantation was 871 acres. One scholar claims that by the end of the colonial period, the low-country slaveholders were “by far the richest single group in British North America.”83 During the same period, as fewer slaveholders engrossed a larger share of wealth, poverty among whites living in the low country increased.84 In the backcountry, or upcountry, slave ownership remained markedly lower, and landownership remained more diffused than in the low country, throughout the antebellum period.85

A study of the Chesapeake region also shows the engrossment of land by fewer owners over time. In that region, middling yeomen farmers were most plentiful in the seventeenth century. In the 1660s, 70 percent of the free population in the Chesapeake region owned land, but with the increase of slavery, the percentage of the free population owning land decreased. By the American Revolution, 50 percent of the free population owned land. In Prince George’s County, Maryland, landlessness grew from 33 percent in 1660 to 50 percent in 1750, 69 percent in 1800, and 75 percent in 1820. At the same time, large landowners were also engrossing a larger share of the slaves. From 1800 to 1820, the percentage of nonslaveholding landowners and landless slave owners dropped. The pattern then in formation was that middling farmers were becoming fewer, with some becoming large slave-owning landowners and others becoming smaller nonslaveholding landowners, tenants, or landless.86

One comparison also demonstrates that these patterns of property ownership strongly correlated to slavery. Property distribution in Georgia during the colonial period more closely resembled the free states of 1860. Land was granted to settlers who worked the land themselves. As late as 1752, fewer than 12 percent of all land grants in Georgia exceeded 50 acres.87 In contrast, the average landholding of a slaveholder in Chester County, Pennsylvania was 222 acres by 1765. At that time, slavery was legal in Pennsylvania, reaching a peak of 6,316 in the countryside by 1780, but was illegal in Georgia.88 These trends began to reverse just before national independence. Georgia began to import slaves legally in the 1750s. From 1750 to 1766, the estimated slave population in Georgia jumped from 500 to 7,800.89 Under opposite influences, Pennsylvania gradually abolished slavery after national independence.

In 1750 the prospects for the broader diffusion of wealth were better in Georgia than in Pennsylvania. But from the late colonial period, land-distribution patterns dramatically changed as slavery grew in Georgia and disappeared in Pennsylvania. By 1860 the total population of Georgia in 1860 was slightly more than 1 million, of whom 44 percent were slaves. The population of Pennsylvania almost reached 3 million free persons. Yet Georgia farms in excess of 500 acres numbered 3,594; in Pennsylvania there were only 76. The modal size of a farm exceeded 100 acres in 51 of 132 Georgia counties, but in only 6 of 65 Pennsylvania counties.90

Wealth in land and slaves concentrated in the hands of the few everywhere slavery spread and increased, until the Civil War. From 1850 to 1860, the percentage of slaveless Southern farms increased from 40 percent to 50 percent, while the fraction of Southern families owning slaves decreased from 36 percent in 1830 to 31 percent in 1850 and then to 25 percent in 1860. Of the 25 percent of slaveholding families, 55 percent fell in the lowest category of slave ownership, of 1 to 5 slaves. Twelve percent of slaveholding families owned the great bulk of slaves.91 At the same time that slave ownership was concentrating, the overall slave population increased from just below 2 million slaves in 1830 to just below 4 million by 1860, and the price of slaves was rising. By the end of the cotton boom of the 1850s, the price of slaves had reached its highest level, linked to the expected profitability of their use. By 1860 a substantial but shrinking minority of slaveholders possessed an increasingly large share of increasing aggregate wealth. The average slaveholder was five times wealthier than the average Northerner and ten times wealthier than the average Southern nonslaveholder. Slaveholders possessed 90 to 95 percent of all agricultural wealth in 1850 and 1860, and their share of wealth was rapidly outpacing the growth of Southern nonslaveholders’ wealth.92

The slaveholders substantiated these observations. Speaking about his state in 1855, Senator Clement Clay of Alabama reported:

Our small planters . . . are going further west and south in search of other virgin lands. . . . Our wealthier planters . . . are buying out their poorer neighbors, extending their plantations, and adding to their slave force. The wealthy few . . . are thus pushing off the many. . . . Of the twenty millions of dollars annually realized from the cotton crop of Alabama, nearly all . . . is re-invested in land and negroes. Thus the white population has decreased and the slave increased, almost pari passu in several counties of our State. In 1825, Madison County cast about 3,000 votes; now she cannot give more than 2,300. In traversing that county, one will discover numerous farm-houses, once the abode of industrious and intelligent freemen, now occupied by slaves, or tenantless, deserted, and dilapidated.93

Gavin Wright explained how slavery caused the results that Clay described. The profits from slaveholding biased reinvestment toward more slaves and land and away from alternative investments. The growth of plantations was limited only by their purchasing power, which was funded by slave labor, and the availability of more land and more slaves. Those with no slaves or fewer slaves could not form capital for reinvestment in slave agriculture as quickly as those who had more slaves and more land. In the free states, the purchasing power of wages enabled free laborers to buy land more easily than to hire labor. Consequently, many owned farms, but the growth of the farms was constrained by the availability of family workers. Northern reinvestments were biased away from agricultural activities and toward labor-saving technology.94 The logic of this explanation suggests that the absence of slavery and universality of family farming in the North increased the scarcity and wages of labor and that in the South slavery depressed the wages of nonslaveholders, which inhibited them from outbidding the slaveholders for slaves and good land.

Some scholars have found that antebellum wages were high in the South, suggesting that slavery did not cause widespread poverty and instead produced general upward mobility.95 Another way to test the purchasing power of wages and upward mobility in the antebellum South relative to the North is to find proof of capital formation rather than to depend on finding reliable wage data. It is evident that Northern free labor could work, save, and accumulate sufficient capital to purchase farms, as free-labor advocates claimed. One scholar studying midwestern capital formation in the nineteenth century concluded, “To one acquainted only with a sophisticated industrial and commercial system, the proportion of farm capital formation created by farm labor, and so in a sense self-financed, is truly astonishing.” If Southern free-labor wages were competitive with Northern wages, we would expect to find evidence that the 75 percent of families who did not own slaves could also work and accumulate sufficient capital from wages to invest in either slaves, land, or nonagricultural economic activities in order to raise their standard of living. But that is not the case. Southern nonslaveholders did not develop nonagricultural economic sectors comparable to the North, nor did more nonslaveholders become slaveholders. The evidence shows that fewer became slaveholders at the same time that aggregate wealth from slaveholding in the South increased. This suggests either that the nonslaveholding families frivolously spent their allegedly higher wages or that they were neither wage wealthy nor asset wealthy and tended to be poor. Wright himself admitted that the prices of slaves were rising beyond the means of more Southerners to purchase them.96

If the slave economy produced high wages, those higher wages would have attracted nonslaveholders to the black belt and induced them to stay, but case studies of different regions at different periods yield evidence that the impoverishment of nonslaveholders was highest where slave density was highest. A study of middle Tennessee found that in 1860, “Virtually all rich families (95 percent) were slaveholders, and virtually all the poor (98 percent) were nonslaveholders.”97 Rather than migrating to the black belt, nonslaveholders fled. In the 1850s the migratory patterns of nonslaveholders were from areas that were more dense to less dense in slaves.98 Another study concludes that rising costs in the black belt induced small farmers to vacate and resettle elsewhere.99

Apart from leaving the slave South, the only apparent alternative left to the nonslaveholder was to head upcountry. The Georgia upcountry was an isolated world of self-sufficient households and farmers who were not prosperous but not groveling poor, either. Unlike Northern farming communities, they cut themselves off from general society and traded with each other, often using barter rather than money.100 But even in the upcountry, where the economic prospects of the nonslaveholder might have been better, broad impoverishment has been found in the late-antebellum period. It is estimated that between 12 and 20 percent of all farm operators in the South Carolina upcountry were landless tenants.101 A general estimate of landless whites for the whole slave South is between 30 and 50 percent of the white Southern population.102

New Northern industrialists were becoming wealthy, in addition to the Southern slaveholders. Noting this, one economic historian collapsed the difference between the two sections, commenting, “In the North the top one percent of the wealth holders were mainly urban merchants and manufacturers whose businesses were based on wage labor, while in the South the top one percent were mainly rural planters whose businesses were based on slave labor.”103 On this basis, it was claimed that the North and South were both “plutocracies.”

Setting aside the fact that this statement passes over wealth mobility, sector diversification, and other metrics of general economic benefit to the citizenry, sovereign rule of the few and concentrated wealth at the top of the scale are not the same. Sometimes they overlap and sometimes they do not. In a model republican society, political and social equality prevails despite property inequality. But in a plutocracy or oligarchy, wealth is the distinctive ruling principle. In an oligarchy wealth determines rank; those unequal in property are absolutely unequal.104 Therefore, even if the same quantitative pattern of wealth distribution prevails in republican and oligarchic society, those patterns produce very different results, because the political standing of wealth is qualitatively different.

Evidence of this qualitative difference between North and South appears early in the early national period. Statesmen from the free states noticed that slavery both widened property inequality and created a ranked political society. After the South Carolina Legislature reopened the slave trade, the U.S. House of Representatives considered taxing slave importations into that state in 1804. In his argument on the House floor, Representative John Lucas of Pennsylvania first spoke of economic harm, stating that by importing more slaves, “you virtually reduce the value of the labor of the whites.” Second, the social and political standing of the free white would decline. He explained, “The rich part of the community will not employ a white man who feels the spirit of a freeman, and who will not submit to be subservient to the caprices of his employer, so long as they can employ a slave whom they can control as they please.”105

Because “the poor white man . . . is entirely dependent on his labor for the support of himself and family,” he will face a choice: be subservient or starve himself and his family. Lucas wanted the tax, because once slaves were imported in South Carolina, they would “soon find their way into the others where slavery is allowed,” and the poor white man’s “relative importance in society will be as nothing.”106

In the Missouri debates of 1819–20, free-state congressmen advanced the same arguments. Speaker of the House John Taylor of New York argued that if Missouri were admitted as a slave state, the only whites who would emigrate would be those who were willing to “take rank with negro slaves,” which was their fate in slave society. He objected to the low esteem in which the slaveholders held all laborers. This banishment of common laborers to a subordinate political station, regardless of their character, education, or talent, was the inevitable consequence of slavery and had no place “in a country like this, where the people are sovereign, and every citizen is entitled to equal rights.”107

In the Senate, Jonathan Roberts of Pennsylvania described the political relationship between labor and employer in the free Northern societies in contrast to the same relationship in the South. In the North, the principles of the Declaration of Independence, which he quoted just previously, governed that relationship.

The white laborer is always a free man, generally an honest man; often an intelligent and informed man. He knows his rights, and understands his duties. Free laborers, who are housekeepers, are seldom without their newspapers and means of information. These channels of intelligence are everywhere established with us. . . . The relation between laborer and employer, where the latter is a freeman, is that of equals. Each looks to the other for the fulfillment of the covenant between them. They often stand in the relation of friends. Their intercourse is almost always respectful and courteous. I have been forcibly struck with how equal a share of happiness, to say the least, was enjoyed by the man of opulence and the cottager in the Northern States.108

An employer and an employee are political and social equals, despite unequal wealth. They are equally free agents contracting with each other. Intelligence, education, and integrity in the discharge of contractual duties command mutual respect, regardless of unequal wealth or the character of their business relationship. Roberts saw a sharp difference between the condescension of his slaveholding colleagues in Congress toward laborers and the equality between employers and employees in his section.

He was a credible witness to this relationship in the North because he had risen from poverty. When he was sixteen, he had been an apprentice for three years, and it was a harsh experience. Such a story of upward mobility by a nonslaveholder in the South was unknown by this time. Taylor asked, “When have we seen a Representative on this floor, from that section of our Union, who was not a slaveholder? Who but slaveholders are elected to their State Legislatures? Who but they are appointed to fill their executive and judicial offices?”109

All of these statesmen saw that slavery and republicanism were mutually hostile in one important respect. They argued that slavery blocked the upward mobility of free labor and, worse, that within the domain of slavery, economic standing determined social and political rank, destroying republican equality. These were the same arguments advanced thirty years later by Republicans. Some scholars detached these later arguments from their longer tradition, grouped and misinterpreted them, claiming that “Free labor” was a distinct ideology conjured by the Republican Party in the 1850s to counter Southern statesmen’s praise of slavery and critiques of nascent modern industrial capitalism in the North.110 On the contrary, American critics of slavery always recognized that the presence of slavery precluded the possibility of genuine republican citizenship, informed by the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

Economic inequalities determined ranks in Southern political society because republican equality was unstable in the South, and this fact was also recognized in the early national period. In 1785 Jefferson considered the difference between northern and southern character. His list of specific contrasts hit upon one that illustrated the general difference between a ranked and an equal society and showed that the foundations of oligarchic and republican political societies were already entrenched in the North and South, respectively. He wrote that southerners were “zealous for their own liberties, but trampling on those of others,” whereas northerners were “jealous of their own liberties, and just to those of others.”111 In this contrast, Jefferson revealed his preference for northern character, if we use the Declaration as his critical standard. Northerners respected the dominion that nature’s God had allotted in equal measure to each person and were protective of the dominion allotted to each one of themselves. Jefferson’s approval of “jealousy” is implicit in the Declaration, in which he wrote that it is the right and duty of a people to rebel against encroachments upon their personal dominion of liberty. Jealousy protects what belongs to you by natural right, and justice respects what belongs to others by natural right. A political society of such individuals is a coequal republican people, despite their inequalities in other respects, including inequality in wealth.

Jefferson’s disapproval of “zeal” is also implicit in the Declaration. Zeal is passionately seeking things that you do not possess, that is, things that are in excess of what is already assigned to you by natural right. To acquire those things, Jefferson wrote, southerners trampled on others. In southern society, liberty was not fixed, but floating, and the southern man expected himself and his neighbors to act upon this knowledge.

In this short strip of text, Jefferson laid one hand on the beating heart of republican society and the other on the beating heart of oligarchy. The principles found in the Declaration could be abstracted from northern conduct but not from southern conduct. The implication in this evidence is that Jefferson knew that southern society needed reform in order to become republican.

Reformation was unsuccessful. In 1830 a North Carolina abolitionist echoed Jefferson, observing that southern society had become careless toward and covetous of the rights of others. He attributed the origin of that carelessness and covetousness to the effect of slaveholding on those with more “wealth and affluence.” The result was that “the same contempt which they cherish for the negro they . . . cherish towards the white peasantry.” Anyone “who will oppress and abuse his own slaves, will also . . . oppress his indigent neighbour, or any one else over whom he may have gained an advantage.” This effect of slavery was not restricted to the slaveholders. Everyone who had some advantage over another used it to oppress whom they could. He added that this tendency was “common among the wealthy, and by far too common with the middle classes of our citizens,” striking “at the root of our republican institutions, and if suffered to become sufficiently strong, would overturn even our liberty itself.”112 He recognized the development of a haughty ruling class, and much more. He saw that oppression of the stronger over the weaker was becoming general throughout slave society.

Eventually, the law formally established ranks of the stronger over the weaker, determined by wealth. A study of local legal records in North Carolina and South Carolina has found evidence that economic standing determined political standing in law.113 Between the 1820s and 1840s, slave-state law recombined elements drawn from the liberal conception of rights and possessions and created a new doctrine. The new legal order entitled those with a larger share of possessions to a larger share of rights. This change meant that the law transformed the right to liberty into an alienable possession. In contrast, the founding idea of American republicanism is that one’s rights are fixed by nature and fixed in equal measure for each person.

By then, the political development of the South was heading in a direction opposite to republicanism. Around this same time when Southern law was undergoing change, Southern statesmen, led by John C. Calhoun, began to praise slavery, which destabilized republican equality, and to denounce the standard of justice in the Declaration by which Jefferson had criticized Southern political character. Calhoun corrected their Southern forebears, who had said that slavery was “a moral and political evil.” Those old beliefs were “folly and delusion.” Instead, he attacked the basis of their antislavery and republican convictions, saying that the principle “all men are born free and equal” was “the most false and dangerous of all political errors.”114 That principle was dangerous only to oligarchy and slavery, but not to republicanism.

The new legal standing of wealth and the decline of natural equality correlated. By making relative wealth the basis of rights, the slave South made rights alienable and reintroduced domination as a lawful principle of civilized government. The law promised to reward the covetousness of the rich for the liberty of the many. Superior success and power conferred the right of one to dominate the other. The weak were contemptible objects of paternal care, not equals in liberty.