Chapter 11. Risk management: Planning for the unknown

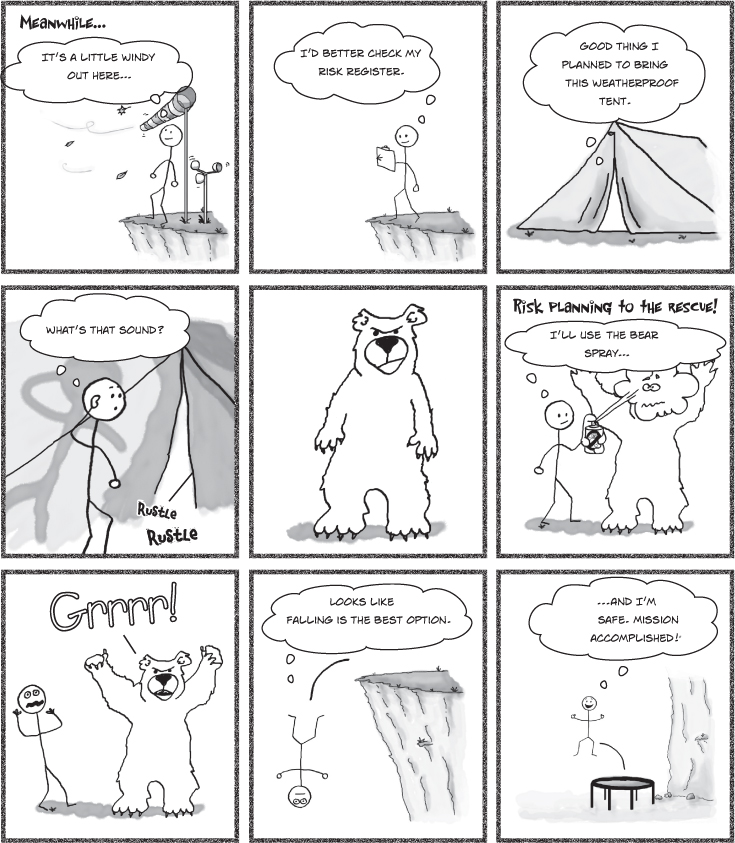

Even the most carefully planned project can run into trouble. No matter how well you plan, your project can always run into unexpected problems. Team members get sick or quit, resources that you were depending on turn out to be unavailable—even the weather can throw you for a loop. So does that mean that you’re helpless against unknown problems? No! You can use risk planning to identify potential problems that could cause trouble for your project, analyze how likely they’ll be to occur, take action to prevent the risks you can avoid, and minimize the ones that you can’t.

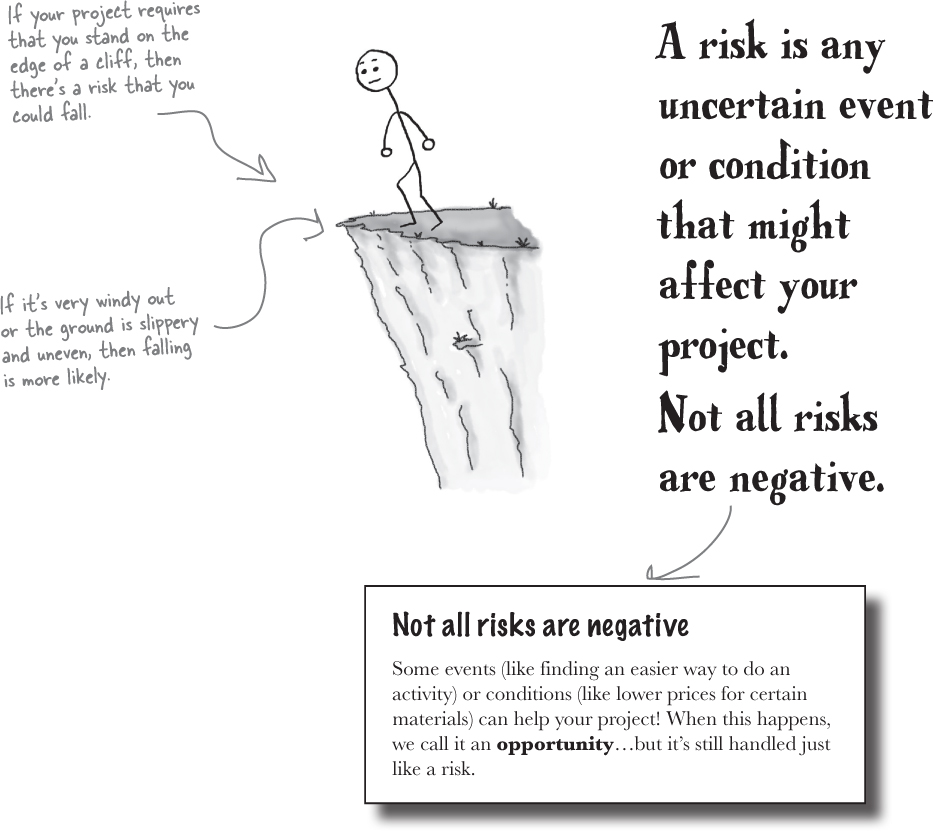

What’s a risk?

There are no guarantees on any project! Even the simplest activity can run into unexpected problems. Any time there’s anything that might occur on your project and change the outcome of a project activity, we call that a risk. A risk can be an event (like a fire), or it can be a condition (like an important part being unavailable). Either way, it’s something that may or may not happen…but if it does, you will be forced to change the way you and your team work on the project.

How you deal with risk

When you’re planning your project, risks are still uncertain: they haven’t happened yet. But eventually, some of the risks that you plan for do happen. And that’s when you have to deal with them. There are five basic ways to handle a risk:

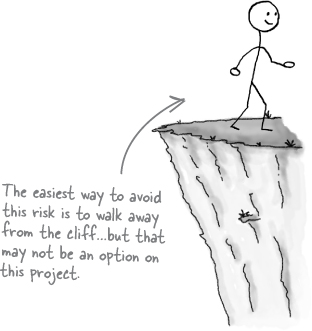

Avoid

The best thing that you can do with a risk is avoid it—if you can prevent it from happening, it definitely won’t hurt your project.

Mitigate

If you can’t avoid the risk, you can mitigate it. This means taking some sort of action that will cause it to do as little damage to your project as possible.

Transfer

One effective way to deal with a risk is to pay someone else to accept it for you. The most common way to do this is to buy insurance.

Accept

When you can’t avoid, mitigate, or transfer a risk, then you have to accept it. But even when you accept a risk, at least you’ve looked at the alternatives and you know what will happen if it occurs.

Escalate

If the risk is not in your project’s scope, you might need to tell somebody else about it to find an appropriate response.

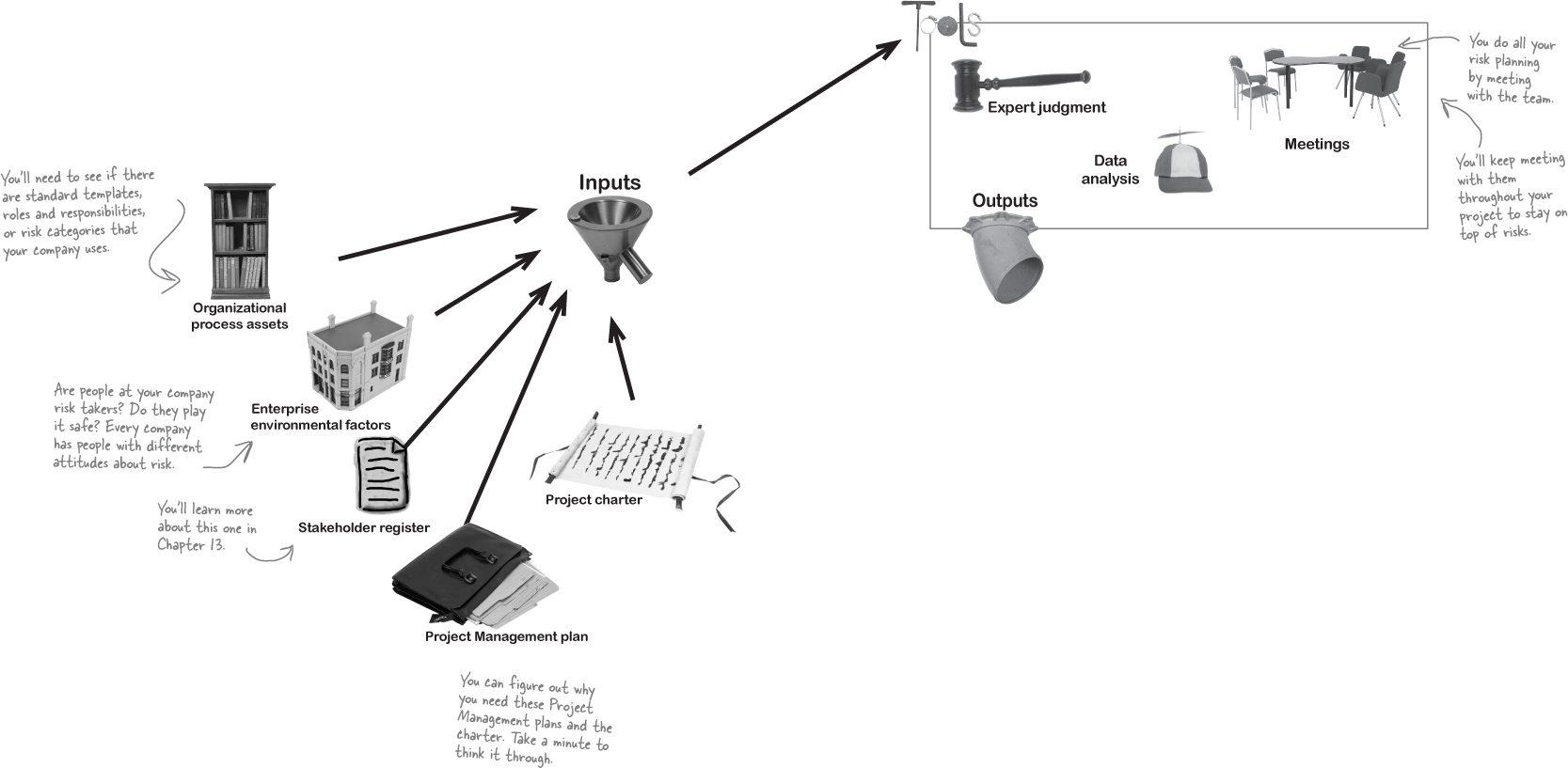

Plan Risk Management

By now, you should have a pretty good feel for how each of the planning processes works. The past few knowledge areas started out with their own planning process, and Risk Management is no different. You start with the Plan Risk Management process, which should look very familiar to you.

Note

By the time a risk actually occurs on your project, it’s too late to do anything about it. That’s why you need to plan for risks from the beginning and keep coming back to do more planning throughout the project.

The Risk Management plan is the only output

It tells you how you’re going to handle risk on your project—which you probably guessed, since that’s what management plans do. It says how you’ll assess risk on the project, who’s responsible for doing it, and how often you’ll do risk planning (since you’ll have to meet about risk planning with your team throughout the project).

The plan has parts that are really useful for managing risk:

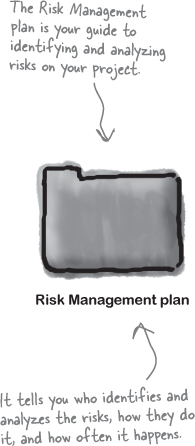

It has a bunch of risk categories that you’ll use to classify your risks. Some risks are technical, like a component that might turn out to be difficult to use. Others are external, like changes in the market or even problems with the weather. Risk categories help you to build a risk breakdown structure (RBS).

It has a bunch of risk categories that you’ll use to classify your risks. Some risks are technical, like a component that might turn out to be difficult to use. Others are external, like changes in the market or even problems with the weather. Risk categories help you to build a risk breakdown structure (RBS). You’ll need to describe the methods and approach you’ll use for identifying and classifying risks on your project. This section of the document is called the methodology.

You’ll need to describe the methods and approach you’ll use for identifying and classifying risks on your project. This section of the document is called the methodology. It’s important to come up with a plan to help you figure out how big a risk’s impact is and how likely a risk is to happen. The impact tells you how much damage the risk will cause to your project. A lot of projects classify impact on a scale from minimal to severe, or from very low to very high. This section of the document is called the definitions of probability and impact.

It’s important to come up with a plan to help you figure out how big a risk’s impact is and how likely a risk is to happen. The impact tells you how much damage the risk will cause to your project. A lot of projects classify impact on a scale from minimal to severe, or from very low to very high. This section of the document is called the definitions of probability and impact.

Use a risk breakdown structure to categorize risks

You should build guidelines for risk categories into your Risk Management plan, and the easiest way to do that is to use a risk breakdown structure (RBS). Notice how it looks a lot like a WBS? It’s a similar idea—you come up with major risk categories, and then decompose them into more detailed ones.

Anatomy of a risk

Once you’re done with Plan Risk Management, there are four more Risk Management processes that will help you and your team come up with the list of risks for your project, analyze how they could affect it, and plan how you and your team will respond if any of the risks materialize when you’re executing it.

All four of these Risk Management processes are in the Planning process group—you need to plan for your project’s risks before you start executing the project.

Note

There are two more Risk Management processes. You already saw Plan Risk Management. There’s also a Monitoring and Controlling process called Monitor Risks that you use when a risk actually materializes.

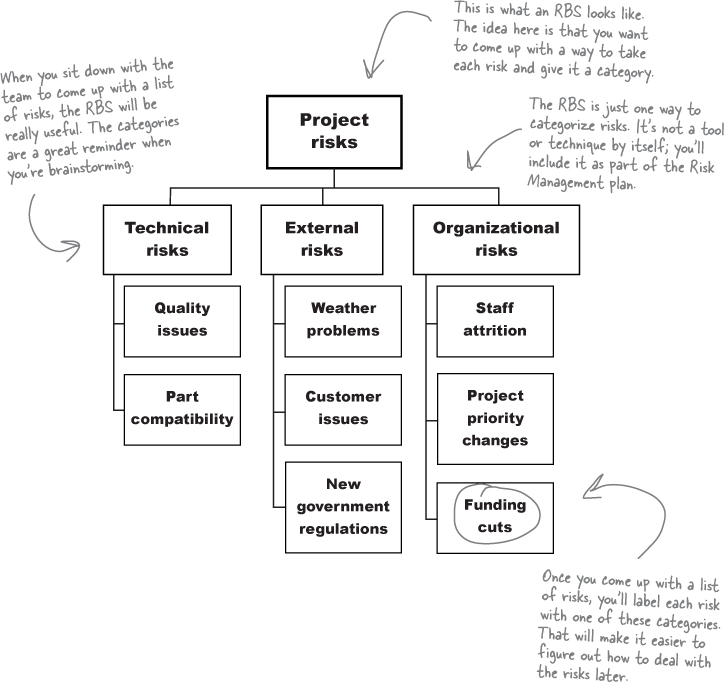

What could happen to your project?

You can’t plan for risks until you’ve figured out which ones you’re likely to run into. That’s why the next Risk Management process is Identify Risks. The idea is that you want to figure out every possible risk that might affect your project. Don’t worry about how unlikely the risk is, or how bad the impact would be—you’ll figure that stuff out later.

The goal of all of the risk planning processes is to produce the risk register. That’s your main weapon against risk.

Data-gathering techniques for Identify Risks

You probably already guessed that the goal of Identify Risks is to identify risks—seems pretty obvious, right? And the most important way to identify those risks is to gather data from the team. That’s why the first—and most important—technique in Identify Risks is called data-gathering techniques. These are time-tested and effective ways to get data from your team, stakeholders, and anyone else who might have data on risks.

Useful data gathering techniques

There are a lot of different ways that you can find risks on your project. But there are only a few that you’re most likely to use—and those are the ones that you will run across on the exam.

Brainstorming is the first thing you should do with your team. Get them all together in a room, and start pumping out ideas. Brainstorming sessions always have a facilitator to lead the team and help turn their ideas into a list of risks.

Note

The facilitator is really important—without her, it’s just a disorderly meeting with no clear goal.

Interviews are a really important part of identifying risk. Try to find everyone who might have an opinion and ask them about what could cause trouble on the project. The sponsor or client will think about the project in a very different way than the project team.

Note

The team usually comes up with risks that have to do with building the product, while the sponsor or someone who would use the product will think about how it could end up being difficult to use.

Checklist analysis means using checklists that you developed specifically to help you find risks. Your checklist might remind you to check certain assumptions, talk to certain people, or review documents you might have overlooked.

Note

The RBS you created in Plan Risk Management is a good place to start for this. You can use all the risks you categorized in it as a jumping-off point.

More Identify Risks techniques

Even though gathering data is the biggest part of Identify Risks, it’s not the only part of it. There are other tools and techniques that you’ll use to make sure that the risk register you put together lists as many risks as possible. The more you know about risk going into the project, the better you’ll handle surprises when they happen. And that’s what these tools and techniques are for—looking far and wide to get every risk possible.

Data analysis tools and techniques

Document analysis is when you look at plans, requirements, documents from your organizational process assets, and any other relevant documents that you can find to squeeze every possible risk out of them.

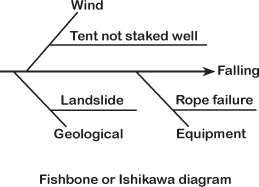

Root-cause identification is analyzing each risk and figuring out what’s actually behind it. Even though falling off of the cliff and having your tent blow away are two separate risks, when you take a closer look you might find that they’re both caused by the same thing: high winds, which is the root cause for both of them. So you know that if you get high winds, you need to be on the lookout for both risks!

SWOT analysis lets you analyze strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. You’ll start by brainstorming strengths and weaknesses, and then examine the strengths to find opportunities, and the weaknesses to identify threats to the project.

Assumptions and constraint analysis is what you’re doing when you look over your project’s assumptions. Remember how important assumptions were when you were estimating the project? Well, now it’s time to look back at the assumptions you made and make sure that they really are things you can assume about the project. Wrong assumptions are definitely a risk.

Interpersonal and team skills help the team to get broad participation in risk identification. Specifically, the facilitation skill is important to this process.

Prompt lists are lists of risk categories that you and the team use to jog your memory when you’re identifying risks. You might use the risk categories from the lowest level of the risk breakdown structure to get the team started thinking about risks that could occur on your project as an example.

Expert judgment lets you rely on past experience to identify risks.

Meetings are where your team gets together to identify risks as a group.

Where to look for risks

A good way to understand risks for the exam is to know where they come from. If you start thinking about how you find risks on your project, it will help you figure out how to handle them.

Here are a few things to keep in mind when you’re looking for risks:

RESOURCES ARE A GOOD PLACE TO START.

Have you ever been promised a person, equipment, conference room, or some other resource, only to be told at the last minute that the resource you were depending on wasn’t available? What about having a critical team member get sick or leave the company at the worst possible time? Check your list of resources. If a resource might not be available to you when you need it, then that’s a risk.THE CRITICAL PATH IS FULL OF RISKS.

Remember the critical path method from Chapter 6? Well, an activity on the critical path is a lot riskier than an activity with plenty of float, because any delay in that activity will delay the project.Note

If an activity that’s not on the critical path has a really small float, that means a small problem could easily cause it to become critical—which could lead to big delays in your project.

”WHEN YOU ASSUME...”

Have you ever heard that old saying about what happens when you assume? At the beginning of the project, your team had to make a bunch of assumptions in order to do your estimates. But some of those assumptions may not actually be true, even though you needed to make them for the sake of the estimate. It’s a good thing you wrote them down—now it’s time to go back and look at that list. If you find some of them that are likely to be false, then you’ve found a risk.LOOK OUTSIDE YOUR PROJECT.

Is there a new rule, regulation, or law being passed that might affect your project? A new union contract being negotiated? Could the price of a critical component suddenly jump? There are plenty of things outside of your project that are risks—and if you identify them now, you can plan for them and not be caught off guard.Note

Finding risks means talking to your team and being creative. Risks can be anywhere.

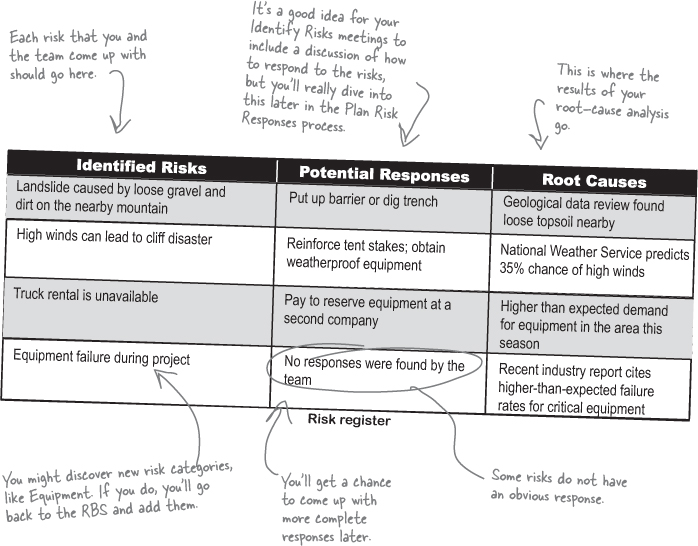

Now put it in the risk register

The point of the Identify Risks process is to…well, identify risks. But what does that really give you? You need to know enough about each risk to analyze it and make good decisions about how to handle it. So when you’re doing interviews, leading brainstorming sessions, analyzing assumptions, gathering expert opinions, and using the other Identify Risks tools and techniques, you’re gathering exactly the things you need to add to the risk register.

The other major output of the Identify Risks process is the risk report. As you work through all of the Risk Management process, you’ll be compiling a report of the sources of risk to your project and summary-level information.

Note

While you identify risks, you might find changes to your assumption log, issue log, or lessons learned register.

Rank your risks

It’s not enough to know that risks are out there. You can identify risks all day long, and there’s really no limit to the number of risks you can think of. But some of them are likely to occur, while others are very improbable. It’s the ones that have much better odds of happening that you really want to plan for.

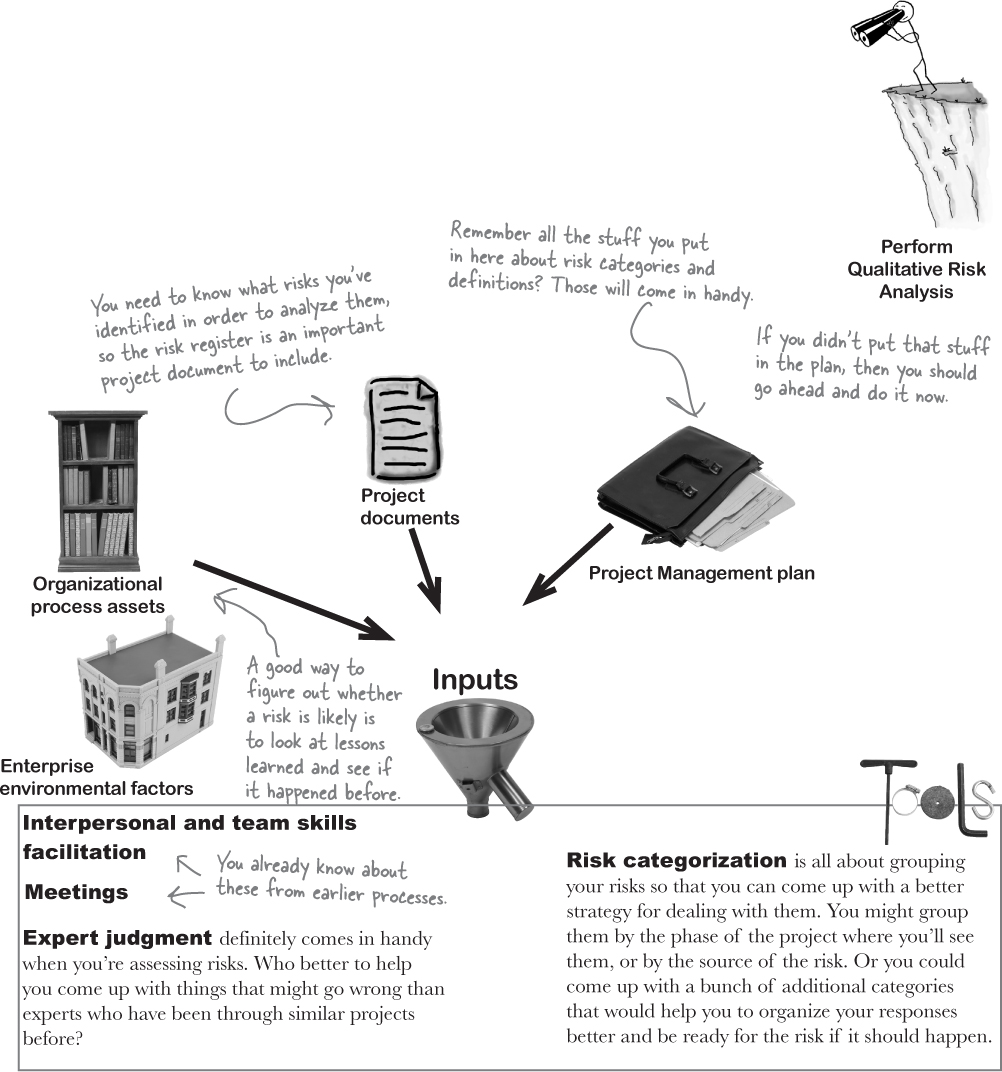

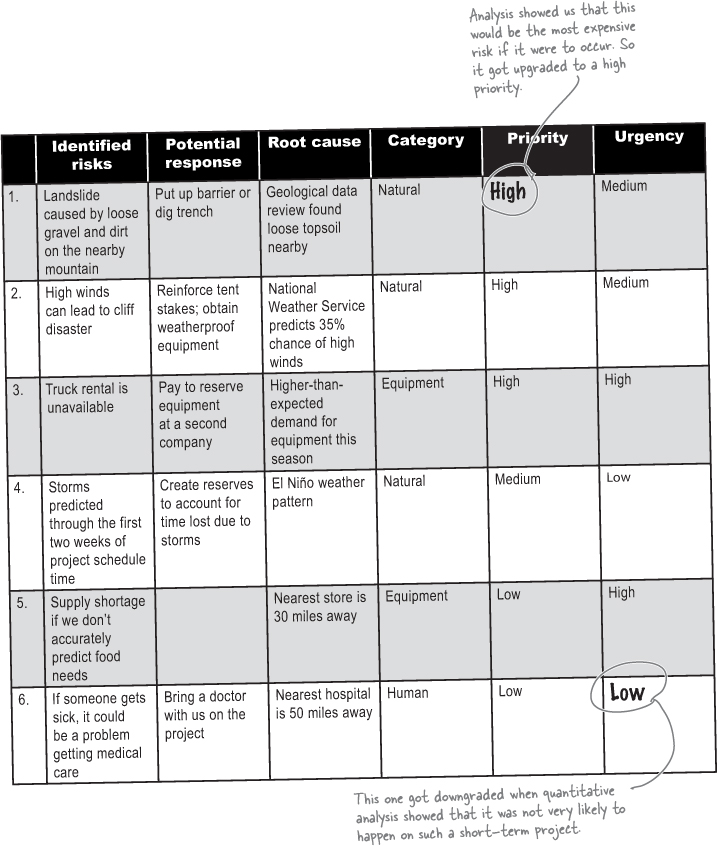

Besides, some risks will cause a whole lot of damage to your project if they happen, while others will barely make a scratch…and you care much more about the risks that will have a big impact. That’s why you need the next Risk Management process, Perform Qualitative Risk Analysis—so you can look at each risk and figure out how likely it is and how big its impact will be.

Examine each risk in the register

Not all risks are created equal. Some of them are really likely to happen, while others are almost impossible. One risk will cause a catastrophe on your project if it happens; another will just waste a few minutes of someone’s time.

Data gathering

Interviews are a great way to get a sense for how important or likely people think a risk is.

Data analysis

Risk data quality assessment means making sure that the data you’re using in your risk assessment is accurate. Sometimes it makes sense to bring in outside experts to check out the validity of your risk assessment data. Sometimes you can even confirm the quality of the data on your own, by checking some sample of it against other data sources.

Assessment of other risk parameters is about urgency and criticality of risks. One way to assess these parameters is to check out how soon you’re going to need to take care of a particular risk. If a risk is going to happen soon, you’d better have a plan for how to deal with it soon, too.

Data representation

A Probability and impact matrix is a table where all of your risks are plotted out according to the values you assign. It’s a good way of looking at the data so you can more easily make judgments about which risks require a response. The ones with the higher numbers are more likely to happen and will have a bigger impact on your project if they do. So you’d better figure out how to handle those.

Hierarchical charts show how risks relate to each other. Most charts are organized by risk category so that teams can plan risk responses by category as well.

Risk probability and impact assessment is one of the best ways to be sure that you’re handling your risks properly by examining how likely they are to happen, and how bad (or good) it will be if they do. This process helps you assign a probability to the likelihood of a risk occurring, and then figure out the actual cost (or impact) if it does happen. You can use these values to figure out which of your risks need a pretty solid mitigation plan, and which can be monitored as the project goes on.

| Probability | P&I | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| .9 | .09 | .27 | .45 | .63 | .81 |

| .7 | .07 | .21 | .35 | .49 | .63 |

| .5 | .05 | .15 | .25 | .35 | .45 |

| .3 | .03 | .09 | .15 | .21 | .27 |

| .1 | .01 | .03 | .05 | .07 | .09 |

| Impact | .1 | .3 | .5 | .7 | .9 |

there are no Dumb Questions

Q: Who does Perform Qualitative Risk Analysis?

A: The whole team needs to work on it together. The more of your team members who are helping to think of possible risks, the better off your plan will be. Everybody can work together to think of different risks to their particular part of the work, and that should give an accurate picture of what could happen on the project.

Q: What if people disagree on how to rank risks?

A: There are a lot of ways to think about risks. If a risk has a large impact on your part of the project or your goals, you can bet that it will seem more important to you than the stuff that affects other people in the group. The best way to keep the right perspective is to keep everybody on the team evaluating risks based on how they affect the overall project goals. If everyone focuses on the effect each risk will have on your project’s constraints, risks will get ranked in the order that is best for everybody.

Q: Where do the categories come from?

A: You can create categories however you want. Usually, people categorize risks in ways that help them come up with response strategies. Some people use project phase. That way, they can come up with a risk mitigation plan for each phase of a project, and they can cut down on the information they need to manage throughout. Some people like to use the source of the risk as a category. If you do that, you can find mitigation plans that can help you deal with each source separately. That might come in handy if you are dealing with a bunch of different contractors or suppliers and you want to manage the risks associated with each separately.

Q: How do I know if I’ve got all the risks?

A: Unfortunately, you never know the answer to that one. That’s why it’s important to keep monitoring your risk register throughout the project. It’s important that you are constantly updating it and that you never let it sit and collect dust. You should be looking for risks throughout all phases of your project, not just when you’re starting out.

Q: What’s the point in even tracking low-priority risks? Why have a watch list at all?

A: Actually, watch lists are just a list of all of the risks that you want to monitor as the project goes on. You might be watching them to see if conditions change and make them more likely to happen. By keeping a watch list, you make sure that all of the risks that seem low priority when you are doing your analysis get caught before they cause serious damage if they become more likely later in the project.

The conditions that cause a risk are called triggers. So, say you have a plan set up to deal with storms, and you know that you might track a trigger for lightning damage, such as a thunderstorm. If there’s no thunderstorm, it’s really unlikely that you will see lightning damage, but once the storm has started, the chance for the risk to occur skyrockets.

Q: I still don’t get the difference between priority and urgency.

A: Priority tells you how important a risk is, while urgency tells you when you need to deal with it. Some risks could be high priority but low urgency, which means that they’re really important, but not time-critical. For example, you might know that a certain supplier that provides critical equipment will go out of business in six months, and you absolutely need to find a new supplier. But you have six months to do it. Finding a new supplier is a high priority, because your project will fail if it’s not taken care of. But it’s not urgent—even if it takes you four months to find a new supplier, nothing bad will happen.

The conditions that cause a risk are called triggers. You use a watch list to stay on top of them.

Qualitative vs. quantitative analysis

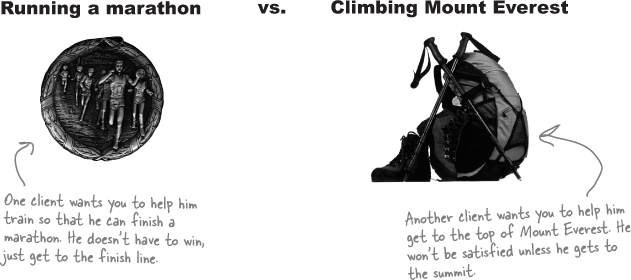

Let’s say you’re a fitness trainer, and your specialty is helping millionaires get ready for major endurance trials. You get paid the same for each job, but the catch is that you get paid only if they succeed. Which of these clients would you take on?

It’s much more likely that you can get even an out-of-shape millionaire to finish a marathon than it is that you can get one to climb Mount Everest successfully.

In fact, since the 1950s, 10,000 people have attempted to climb Mount Everest, and only 1,200 have succeeded, while 200 have died. Your qualitative analysis probably told you that the climbing project would be the riskier of the two. But having the numbers to back up that judgment is what quantitative analysis is all about.

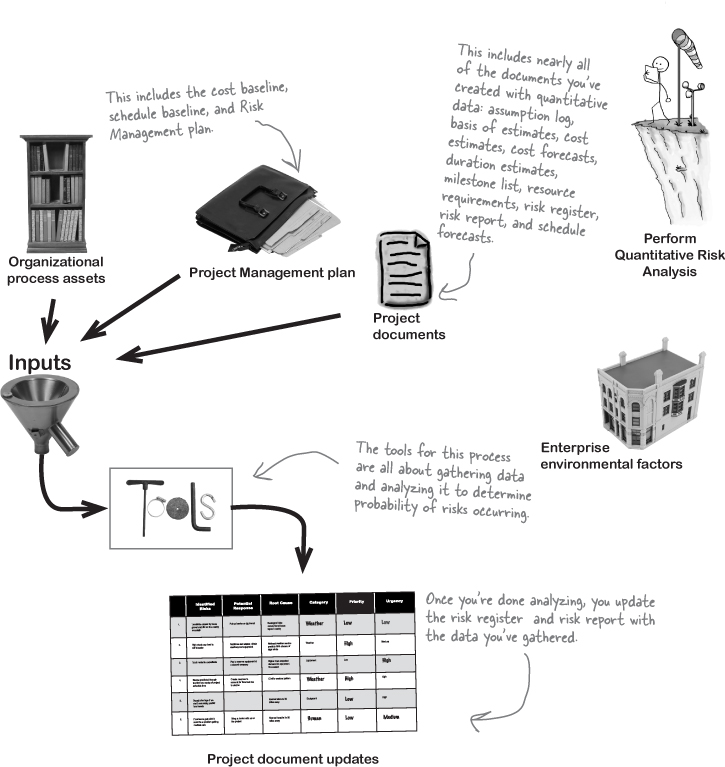

Perform Quantitative Risk Analysis

Once you’ve identified risks and ranked them according to the team’s assessment, you need to take your analysis a little further and make sure that the numbers back you up. Sometimes you’ll find that your initial assessment needs to be updated when you look into it further.

First gather the data…

Quantitative tools are broken down into three categories: the ones that help you get more data about risks, the ones that help you to analyze the data you have, and expert judgment to help you put it all together. The tools for gathering data focus on gathering numbers about the risks you have already identified and ranked. These tools are called data gathering and representation techniques.

Interviewing

Sometimes the best way to get hard data about your risks is to interview people who understand them. In a risk interview, you might focus on getting three-point cost estimates so that you can come up with a budget range that will help you mitigate risks later. Another good reason to interview is to establish ranges of probability and impact, and document the reasons for the estimates on both sides of the range.

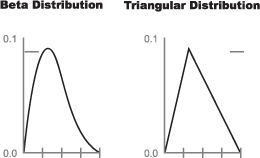

Representations of uncertainty

Sometimes taking a look at your time and cost estimate ranges in terms of their distribution will help you generate more data about them. You probably remember these distribution curves from your probability and statistics classes in school. Don’t worry: you won’t be asked to remember the formal definition of probability distributions or even to be able to create them. You just need to know that they are another way of gathering data for quantitative analysis.

Expert judgment

It’s always a good idea to contact the experts if you have access to them. People who have a good handle on statistics or risk analysis in general can be helpful when you are doing quantitative analysis. Also, it’s great to hear from anybody who has a lot of experience with the kind of project you are creating.

Interpersonal and team skills: facilitation

You’ll need to be skilled at facilitation to help the team come to its quantitative representations of risk. Working with the team while they model out uncertainty and use it to drive decisions is an important part of this process.

…then analyze it

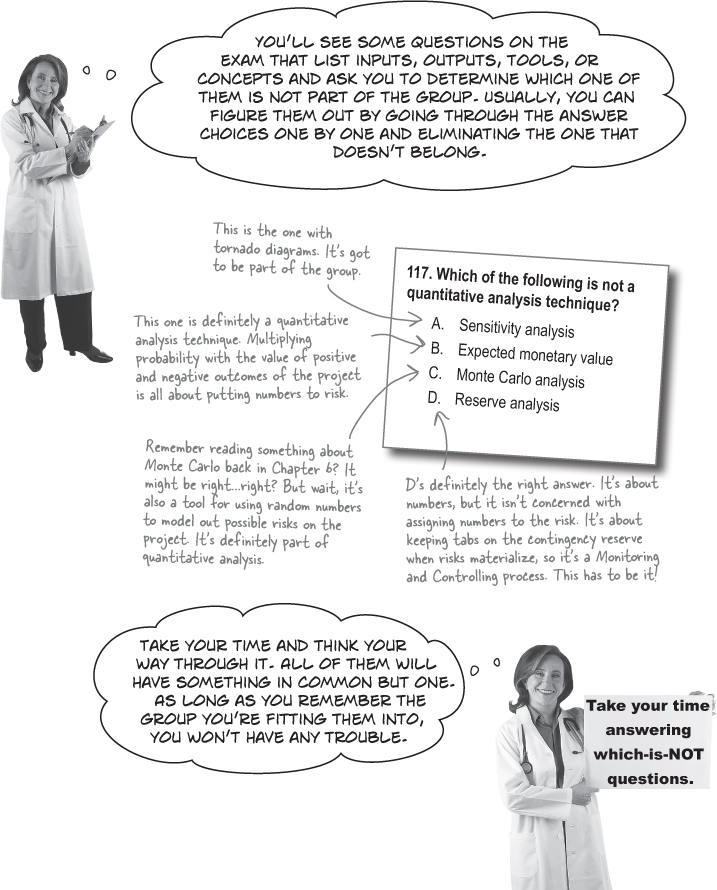

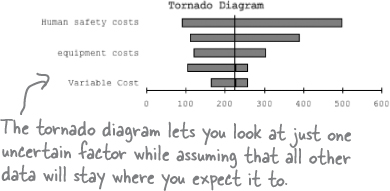

Now that you have all the data you can get about your risk register, it’s time to analyze that data. Most of the tools for analyzing risk data are about figuring out how much the risk will end up costing you. There are four tools that fall under the category of data analysis: sensitivity analysis, decision tree analysis, simulations, and influence diagrams.

Sensitivity analysis is all about looking at the effect one variable might have if you could completely isolate it. You might look at the cost of a windstorm on human safety, equipment loss, and tent stability without taking into account other issues that might accompany the windstorm (like rain damage or possible debris from nearby campsites). People generally use tornado diagrams to look at a project’s sensitivity to just one risk factor.

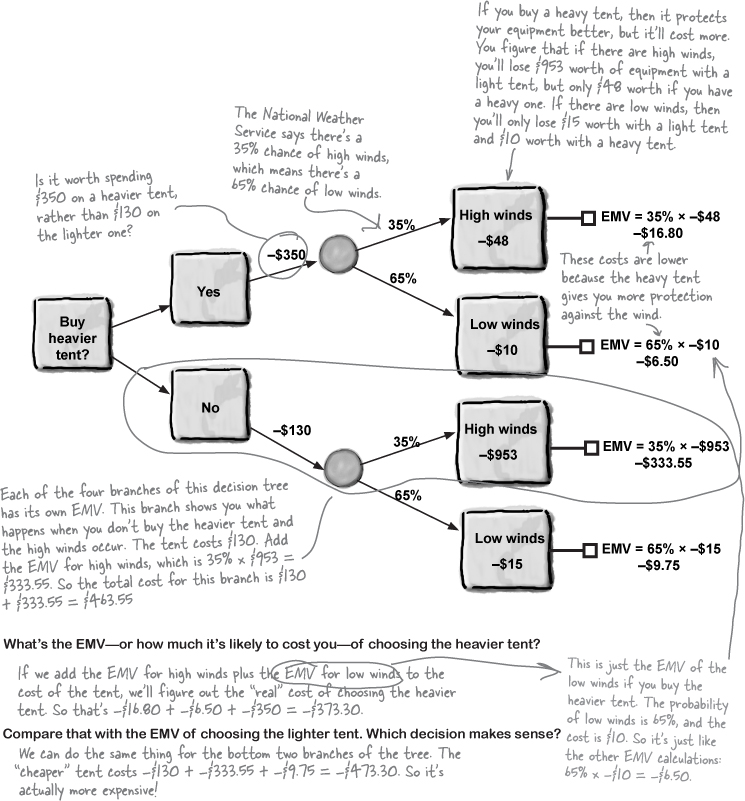

Decision tree analysis lets you examine costs of all of the paths you might take through the project (depending on which risks occur) and assign a monetary value to each decision. So, if it costs $100 to survey the cliff and $20 to stake your tent, choosing to stake your tent after you’ve looked at the cliff has an expected monetary value of $120.

Note

We’ll talk about this in a couple of pages…

Simulation. refers to running your project risks through modeling programs. Monte Carlo analysis is one tool that can randomize the outcomes of your risks and the probabilities of them occurring to help you get a better sense of how to handle the risks you have identified.

Influence Diagrams

It’s valuable to understand the relationships between entities, outcomes, and influences in your project. Influence diagrams show these relationships graphically.

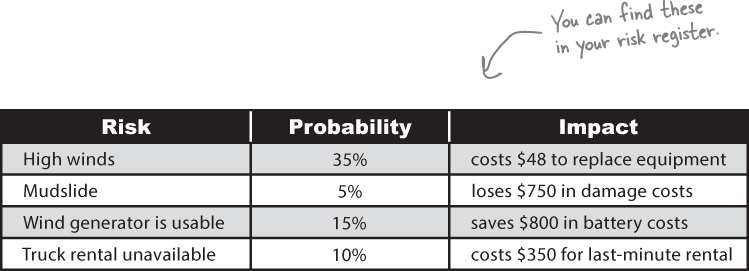

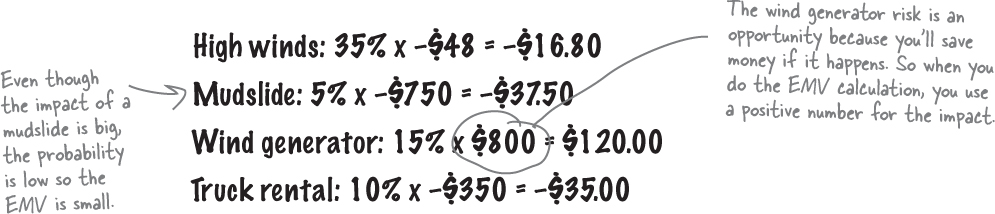

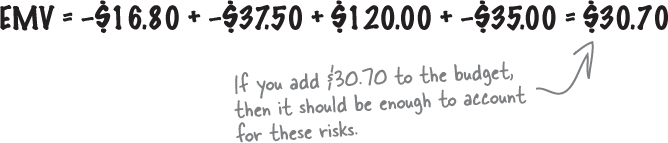

Calculate the expected monetary value of your risks

OK, so you know the probability and impact of each risk. How does that really help you plan? Well, it turns out that if you have good numbers for those things, you can actually figure out how much those risks are going to cost your project. You can do that by calculating the expected monetary value (or EMV) of each risk:

Start with the probability and impact of each risk.

Take the first risk and multiply the probability by the impact. For opportunities, use a positive cost. For threats, use a negative one. Then do the same for the rest of the risks.

Now that you’ve calculated the EMV for each of the risks, you can add them up to find the total EMV for all of them.

Decision tree analysis uses EMV to help you make choices

There’s another way to do EMV—as we mentioned earlier, you can do it visually using a decision tree. This decision tree shows the hidden costs of whether or not you buy a heavier tent. The tent is more expensive—it costs $350, while the lighter tent costs $130. But the heavier tent has better protection against the wind, so if there are high winds, your equipment isn’t damaged.

there are no Dumb Questions

Q: I still don’t get this Monte Carlo stuff. What’s the deal?

A: All you really need to know about Monte Carlo analysis for the test is that it’s a way that you can model out random data using software. In real life, though, it’s a really cool way of trying to see what could happen on your project if risks do occur. Sometimes modeling out the data you already have about your project helps you to better see the real impact of a risk if it did happen.

Q: I can figure out how much the risk costs using EMV, or I can do it with decision tree analysis. Why do I need two ways to do this?

A: That’s a good question. If you take a really careful look at how you do decision tree analysis, you might notice something…it’s actually doing exactly the same thing as EMV. It turns out that those two techniques are really similar, except that EMV does it using numbers and decision tree analysis spells out the same calculation using a picture.

Q: I understand that EMV and decision trees are related, but I still don’t exactly see how.

A: It turns out that there are a lot of EMV techniques, and decision tree analysis is just one of them. But it’s the one you need to know for the test, because it’s the one that helps you make decisions by figuring out the EMV for each option. You can bet that you’ll see a question or two that asks you to calculate the EMV for a project based on decision tree like the one on the facing page. As long as you remember that risks are negative numbers and that opportunities are positive ones, you should do fine.

Q: So are both quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis really just concerned with figuring out the impact of risks?

A: That’s right. Qualitative analysis focuses on the impact as the team judges it in planning. Quantitative analysis focuses on getting the hard numbers to back up those judgments.

Update the risk register based on your quantitative analysis results

When you’ve finished gathering data about the risks, you change your priorities, urgency ratings, and categories (if necessary), and you update your risk register. Sometimes modeling out your potential responses to risk helps you to find a more effective way to deal with them. That’s why the only output of the Perform Quantitative Risk Analysis is project documents updates.

Your risk register should include both threats and opportunities. Opportunities have positive impact values, while threats have negative ones. Don’t forget the plus or minus sign when you’re calculating EMV.

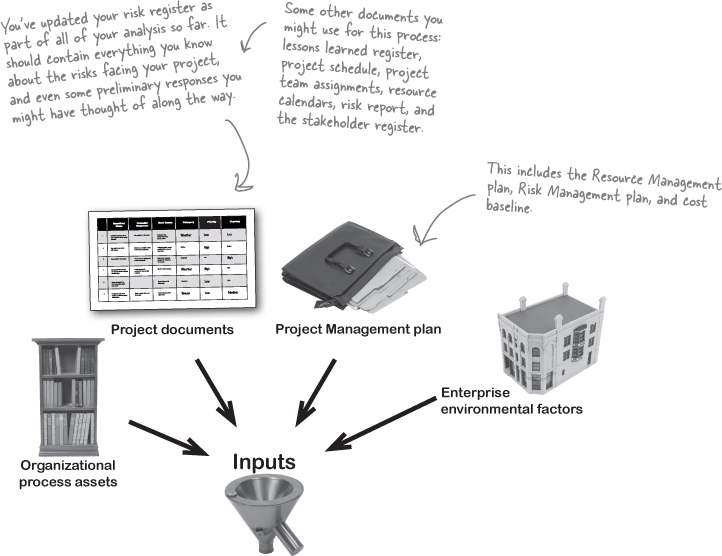

How do you respond to a risk?

After all that analysis, it’s time to figure out what you’re going to do if a risk occurs. Maybe you’ll be able to keep a reserve of money to handle the cost of the most likely risks. Maybe there’s some planning you can do from the beginning to be sure that you avoid it. You might even find a way to transfer some of the risk with an insurance policy.

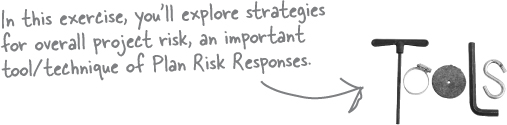

However you decide to deal with each individual risk, you’ll update your risk responses in the risk register to show your decisions when you’re done. When you’re done with Plan Risk Responses, you should be able to tell your change control board what your response plans are and who will be in charge of them so they can use them to evaluate changes.

Plan Risk Responses is figuring out what you’ll do if risks happen.

You might need to reach out to somebody who has dealt with a risk you’ve identified before to understand the best way to respond to it.

Contingent response strategies

Sometimes you need to make contingency plans in case an event occurs in your project. Say you miss an important milestone or a vendor you’re depending on goes out of business. You might put together a plan that would be triggered by that event to keep your project on track.

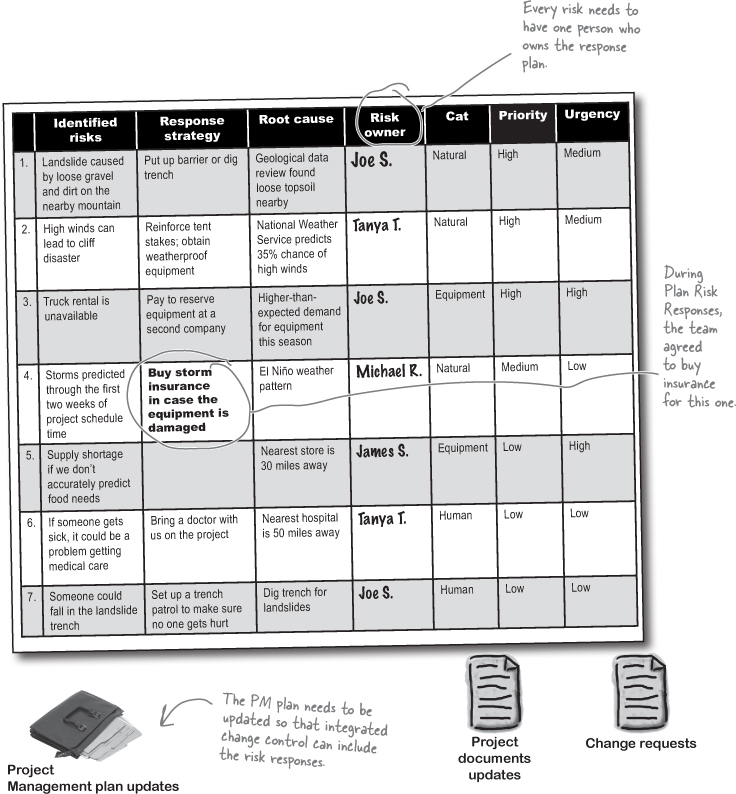

Data gathering: interviews

Interviewing stakeholders to get their opinions on the best way to respond to specific risks is a great way to put together a risk response plan.

Decision making

Interpersonal and team skills: facilitation

Data analysis: alternatives analysis and cost-benefit analysis

You know these data analysis techniques already. They can help you figure out the best way to respond to the risks you’ve identified.

It isn’t always so bad

Remember the strategies for handling negative risks—avoid, mitigate, transfer, accept, and escalate—from earlier? Well, there are strategies for handling positive risks, too. The difference is that strategies for opportunities are all about how you can try to get the most out of them. The strategies for handling negative and positive risks are the tools and techniques for the Plan Risk Responses process.

Note

The strategies for threats are also tools and techniques for this process. They’re the ones you already learned: avoid, mitigate, transfer, accept. and escalate.

Exploit

This is when you do everything you can to make sure that you take advantage of an opportunity. You could assign your best resources to it. Or you could allocate more than enough funds to be sure that you get the most out of it.

Share

Sometimes it’s harder to take advantage of an opportunity on your own. Then you might call in another company to share in it with you.

Enhance

This is when you try to make the opportunity more probable by influencing its triggers. If getting a picture of a rare bird is important, then you might bring more food that it’s attracted to.

Accept

Just like accepting a negative risk, sometimes an opportunity just falls in your lap. The best thing to do in that case is to just accept it!

Escalate

If you found an opportunity that might help your overall company strategy beyond what your project set out to do, you might escalate that opportunity to people who could take advantage of it.

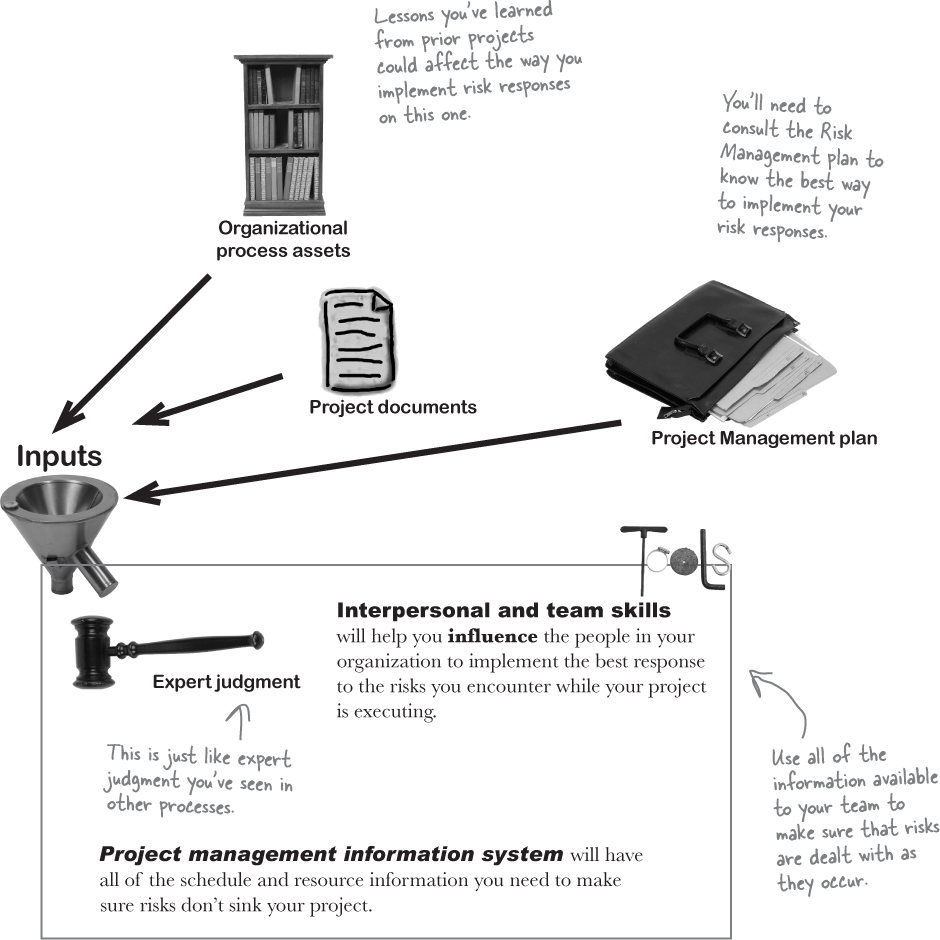

Add risk responses to the register

It’s time to add—you guessed it—more updates to project documents, including the risk register. All of your risk responses will be tracked through change control. Changes that you need to make to the plan will get evaluated based on your risk responses, too. It’s even possible that some of your risk responses will need to be added into your contract.

Implement Risk Responses

Now that you’ve planned responses to risk, you’re ready to put that plan into action. The next process, Implement Risk Responses, is all about what you do when you run into an occurrence of the risks you’ve identified. This is where you actually respond to the risk by doing what’s in your plan.

As you respond to risk, you update your project documents

Think about all of the documents that might need to change as you put your risk responses into action. You might identify new issues that need to be added to the issue log. Or, you could learn something new from a risk that you encounter and need to make an update to the lessons learned register. You could need to change the way your team is assigned in order to respond to a risk that happens. There’s always the possibility that you could need to change the risk register and the risk report themselves as you learn more about the risks you’ve planned for.

Risk response can find even more risks

Secondary risks come from a response you have to another risk. If you dig a trench to stop landslides from taking out your camp, it’s possible for someone to fall into the trench and get hurt.

Residual risks remain after your risk responses have been implemented. So even though you reinforce your tent stakes and get weatherproof gear, there’s still a chance that winds could destroy your camp if they are strong enough.

Risk Management Exposed

Risk Management Exposed

This week’s interview:

Stick figure who hangs out on cliffs

Head First: We’ve seen you hanging out on cliffs for a while now. Apparently, you’ve also been paying people to stand on the cliff for you, or getting a friend to hold a trampoline at the foot of the cliff; we’ve even seen you jump off of it. So now that I’ve finally got a chance to interview you, I want to ask the question on everyone’s mind: “Are you insane? Why do you spend so much time up there?”

Stick Figure: First off, let me dispel a few myths that are flying around out there about me. I’m not crazy, and I’m not trying to get myself killed! Before Risk Management entered my life I, like you, would never have dreamed of doing this kind of thing.

Head First: OK, but I’m a little skeptical about your so-called “Risk Management.” Are you trying to say that because of Risk Management you don’t have to worry about the obvious dangers of being up there?

Stick Figure: No. Of course not! That’s not the point at all. Risk Management means you sit down and make a list of all of the things that could go wrong. (And even all the things that could go right.) Then you really try to think of the best way to deal with anything unexpected.

Head First: So you’re doing this Risk Management stuff to make it less dangerous for you?

Stick Figure: Yes, exactly! By the time I’m standing up there on that cliff, I’ve really thought my way through pretty much everything that might happen up there. I’ve thought through it both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Head First: Quantitatively?

Stick Figure: Yes. You don’t think I’d go up there without knowing the wind speed, do you? Chance of landslides? Storms? The weight of everything I’m carrying? How likely I am to fall in weather conditions? I think about all of that and I measure it. Then I sit down and come up with risk response strategies.

Head First: OK, so you have strategies. Then what?

Stick Figure: Then I constantly monitor my risks while I’m on the cliff. If anything changes, I check to see if it might trigger any of the risks I’ve come up with. Sometimes I even discover new risks while I’m up there. When I do, I just add them to the list and work on coming up with responses for them.

Head First: I see. So you’re constantly updating your list of risks.

Stick Figure: Yes! We call it a risk register. Whenever I have new information, I put it there. It means that I can actually hang out on these cliffs with a lot of confidence. Because, while you can’t guarantee that nothing will go wrong, you can be prepared for whatever comes your way.

Head First: That’s a lot of work. Does it really make a difference?

Stick Figure: Absolutely! I’d never be able to sleep at night knowing that I could fall off the cliff at any time. But I’ve planned for the risks, and I’ve taken steps to stay safe…and I sleep like a baby.

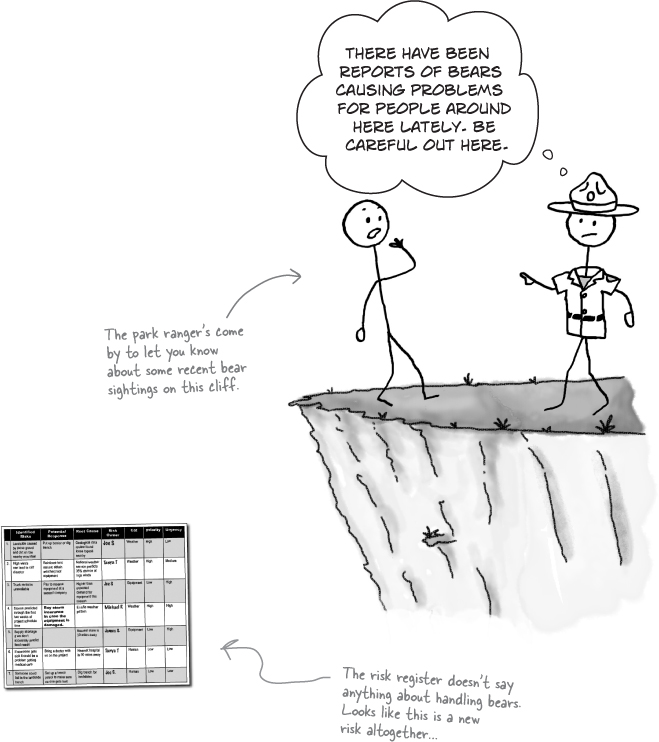

You can’t plan for every risk at the start of the project

Even the best planning can’t predict everything—there’s always a chance that a new risk could crop up that you hadn’t thought about. That’s why you need to constantly monitor how your project is doing compared to your risk register. If a new risk happens, you have a good chance of catching it before it causes serious trouble. When it comes to risk, the earlier you can react, the better for everybody. And that’s what the Monitor Risks process is all about.

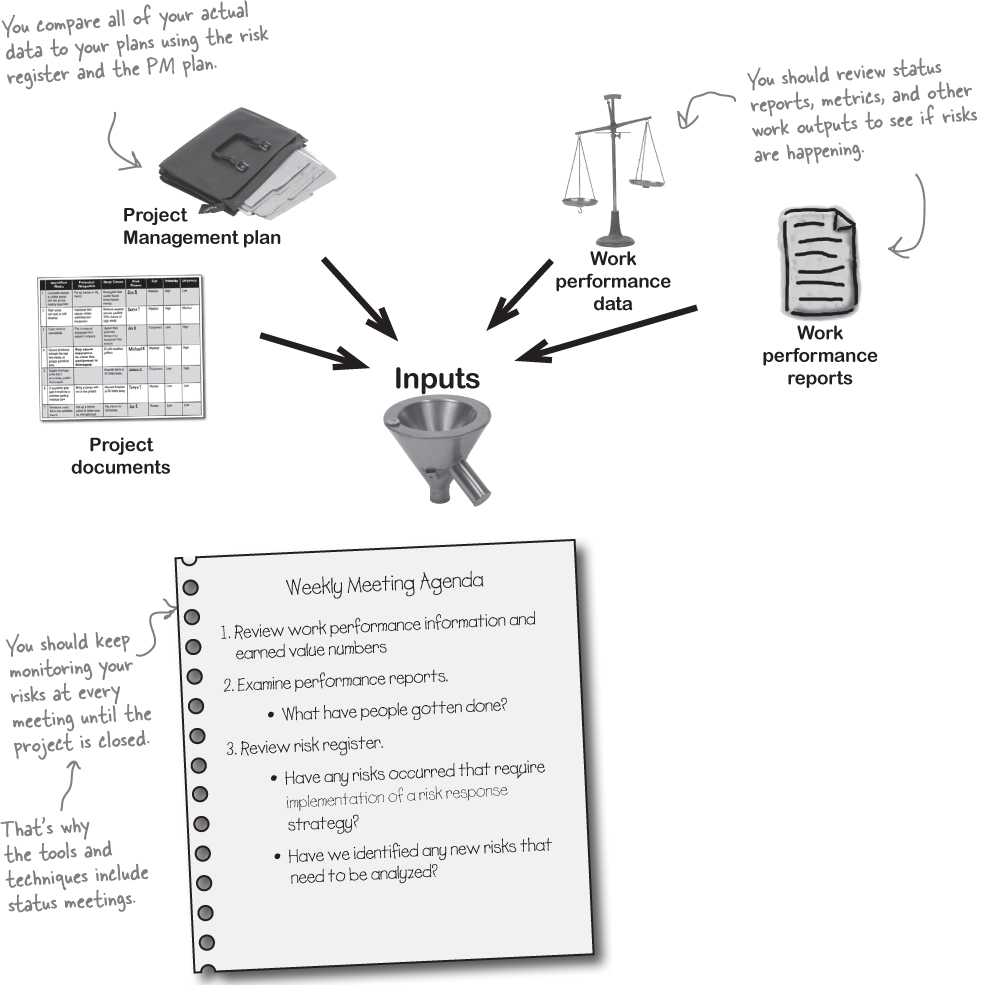

Monitor Risks is another change control process

Risk responses are treated just like changes. You monitor the project in every status meeting to see how the risks in the risk register are affecting it. If you need to implement a risk response, you take it to your change control board, because it amounts to a change that will affect your project constraints.

Risk monitoring should be done at every status meeting.

How to monitor your risks

Monitoring risks means keeping your finger on the pulse of the project. If you are constantly reviewing all of the data your project is producing, you will be able to react quickly if a new risk is uncovered, or if it looks like one of your response strategies needs to spring into action. Without careful monitoring, even your best plans won’t get implemented in time to save your project if a risk happens. Here are the data analysis techniques you’ll need to use when you monitor your risks.

Technical performance analysis

Comparing the actual project performance to the plan is a great way to tell if a risk might be happening. If you find that you’re significantly over budget or behind schedule, a risk could have cropped up that you didn’t take into account. Looking for trends in your defects or schedule variance, for example, might show patterns that indicate that risks have occurred before you would have found that out on your own.

Reserve analysis

Just like you keep running tabs on your budget, you should always know how much money you have set aside for risk response. As you spend it, be sure to subtract it so you know if you have enough to cover all of your remaining risks. If you start to see that your reserves are running low and there are still a lot of risks being identified, you might be in trouble. Keeping tabs on your reserves means that you will always know if you need to set aside more funds or make different choices about how to handle risks as they come up.

Note

Sometimes this kind of reserve is called a “contingency”—because its use is contingent on a certain risk happening.

Analyze the data you gather in project status meetings to determine how your project is managing risk.

More control risk tools and techniques

There are just a few more tools in the Monitor Risks process. They’re all focused on finding new risks if they crop up, dealing with changes to the risks you’ve already planned for, and responding quickly to risks you know how to handle.

Audits are when you have an outside party come in and take a look at your risk response strategies to judge how effective they are. Sometimes risk audits will point out better ways of handling a specific risk so that you can change your response strategy going forward.

Note

Auditors will also look at how effective your overall processes for risk planning are.

Meetings are the most important way to keep the team up to date on risk planning—so important that they should happen throughout the entire project. The more you talk about risks with the team, the better. Every single status meeting should have risk review on the agenda. Status meetings are a really important way of noticing when things might go wrong, and of making sure that you implement your response strategy in time. It’s also possible that you could come across a new opportunity by talking to the team.

Never stop looking for new risks and adapting your strategies for dealing with them.

there are no Dumb Questions

Q: Why do I need to ask about risks at every status meeting?

A: Because a risk could crop up at any time, and you need to be prepared. The better you prepare for risks, the more secure your project is against the unknown. That’s also why the triggers and watch lists are really important. When you meet with your team, you should figure out if a trigger for a risk response has happened. And you should check your watch list to make sure none of your low-priority risks have materialized.

For the test, you need to know that status meetings aren’t just a place for you to sit and ask each member of your team to tell you his or her status. Instead, you use them to figure out decisions that need to be made to keep the project on track or to head off any problems that might be coming up. In your status meetings, you need to discuss all of the issues that involve the whole team and come up with solutions to any new problems you encounter. So, it makes sense that you would use your status meetings to talk about your risk register and make sure that it is always up to date with the latest information.

Q: I still don’t get technical performance analysis. How does it help me find risks?

A: It’s easy to miss risks in your project—sometimes all the meetings in the world won’t help your team see some of them. That’s why a tool like trend analysis can be really useful. Remember the control chart from Chapter 8? This is really similar, and it’s just as valuable. It’s just a way to see if things are happening that you did not plan for.

Q: Hey, didn’t you talk about risks back in the Project Schedule Management chapter too?

A: Wow—it’s great that you remembered that! The main thing to remember about risks from Chapter 6 is that having a very long critical path or, even worse, multiple critical paths, means you have a riskier project. The riskiest is when all of the activities are on the critical path. That means that a delay to even one activity can derail your whole project.

Q: Shouldn’t I ask the sponsor about risks to the project?

A: Actually, the best people to ask about risks are the project team itself. The sponsor knows why the project is needed and how much money is available for it, but from there, it’s really up to the team to manage risks. Since you are the ones doing the work, it makes sense that you would have a better idea of what has gone wrong on similar projects and what might go wrong on this one. Identify Risks, Perform Qualitative and Quantitative Risk Analysis, and Plan Risk Responses are some of the most valuable contributions the team makes to the project. They can be the difference between making the sponsor happy and having to do a lot of apologizing.

Q: Why do we do risk audits?

A: Risk audits are when you have someone from outside your project come in and review your risk register—your risks and your risk responses—to make sure you got it right. The reason we do it is because risks are so important that getting a new set of eyes on them is worth the time.

Q: Hold on, didn’t we already talk about reserves way back in the Cost Management chapter? Why is it coming up here?

A: That’s right, back in Chapter 7 we talked about a management reserve, which is money set aside to handle any unknown costs that come up on the project. That’s a different kind of reserve than the one for controlling risks. The kind of reserve used for risks is called a contingency reserve, because its use is contingent on a risk actually materializing.

Project managers sometimes talk about both kinds of reserves together, because they both have to show up on the same budget. When they do, you’ll sometimes hear talk of “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns.” The management reserve is for unknown unknowns—things that you haven’t planned for but could impact your project. The contingency reserve is for known unknowns, or risks that you know about and explicitly planned for and put in your risk register.

The better you prepare for risks, the more secure your project is against the unknown.

Note

* Note from the authors: We’re not exactly sure why he feels his mission was accomplished after spraying a bear in the face and then jumping off of a cliff. But it seems to work!

Exam Questions

The project manager for a construction project discovers that the local city council may change the building code to allow adjoining properties to combine their sewage systems. She knows that a competitor is about to break ground in the adjacent lot and contacts him to discuss the possibility of having both projects save costs by building a sewage system for the two projects.

This is an example of which strategy?

Mitigate

Share

Accept

Exploit

Which of the following is NOT a risk response technique?

Exploit

Transfer

Mitigate

Collaborate

You are using an RBS to manage your risk categories. What process are you performing?

Plan Risk Management

Identify Risks

Perform Qualitative Risk Analysis

Perform Quantitative Risk Analysis

Which of the following is used to monitor low-priority risks?

Triggers

Watch lists

Probability and Impact matrix

Monte Carlo analysis

You’re managing a construction project. There’s a 30% chance that weather will cause a three-day delay, costing $12,000. There’s also a 20% chance that the price of your building materials will drop, which will save $5,000. What’s the total EMV for both of these?

–$3,600

$1,000

–$2,600

$4,600

Joe is the project manager of a large software project. When it’s time to identify risks on his project, he contacts a team of experts and sends them a list of questions to help them all come up with a list of risks and send it in. What technique is Joe using?

SWOT

Ishikawa diagramming

Interviews

Brainstorming

Susan is the project manager on a construction project. When she hears that her project has run into a snag due to weeks of bad weather on the job site, she says “No problem, we have insurance that covers cost overruns due to weather.” What risk response strategy did she use?

Exploit

Transfer

Mitigate

Avoid

You’re performing Identify Risks on a software project. Two of your team members have spent half of the meeting arguing about whether or not a particular risk is likely to happen on the project. You decide to table the discussion, but you’re concerned that your team’s motivation is at risk. The next item on the agenda is a discussion of a potential opportunity on the project in which you may be able to purchase a component for much less than it would cost to build.

Which of the following is NOT a valid way to respond to an opportunity?

Exploit

Transfer

Share

Enhance

Risks that are caused by the response to another risk are called:

Residual risks

Secondary risks

Cumulative risks

Mitigated risks

What’s the main output of the Risk Management processes?

The Risk Management plan

The risk breakdown structure

Work performance information

The risk register and project documents updates

Tom is a project manager for an accounting project. His company wants to streamline its payroll system. The project is intended to reduce errors in the accounts payable system and has a 70% chance of saving the company $200,000 over the next year. It has a 30% chance of costing the company $100,000.

What’s the project’s EMV?

$170,000

$110,000

$200,000

$100,000

What’s the difference between management reserves and contingency reserves?

Management reserves are used to handle known unknowns, while contingency reserves are used to handle unknown unknowns.

Management reserves are used to handle unknown unknowns, while contingency reserves are used to handle known unknowns.

Management reserves are used to handle high-priority risks, while contingency reserves are used to handle low-priority risks.

Management reserves are used to handle low-priority risks, while contingency reserves are used to handle high-priority risks.

How often should a project manager discuss risks with the team?

At every milestone

Every day

Twice

At every status meeting

Which of the following should NOT be in the risk register?

Watch lists of low-priority risks

Relative ranking of project risks

Root causes of each risk

Probability and Impact matrix

Which of the following is NOT true about Risk Management?

The project manager is the only person responsible for identifying risks

All known risks should be added to the risk register

Risks should be discussed at every team meeting

Risks should be analyzed for impact and priority

You’re managing a project to remodel a kitchen. You find out from your supplier that there’s a 50% chance that the model of oven that you planned to use may be discontinued, and you’ll have to go with one that costs $650 more. What’s the EMV of that risk?

$650

–$650

$325

–$325

Which risk analysis tool is used to model your risks by running simulations that calculate random outcomes and probabilities?

Monte Carlo analysis

Sensitivity analysis

EMV analysis

Delphi technique

A construction project manager has a meeting with the team foreman, who tells him that there’s a good chance that a general strike will delay the project. They brainstorm to try to find a way to handle it, but in the end decide that if there’s a strike, there is no useful way to minimize the impact to the project. This is an example of which risk response strategy?

Mitigate

Avoid

Transfer

Accept

You’re managing a project to fulfill a military contract. Your project team is assembled, and work has begun. Your government project officer informs you that a supplier that you depend on has lost the contract to supply a critical part. You consult your risk register and discover that you did not plan for this. What’s the BEST way to handle this situation?

Consult the Probability and Impact matrix

Perform Quantitative and Qualitative Risk Analysis

Recommend preventive actions

Look for a new supplier for the part

Which of the following BEST describes risk audits?

The project manager reviews each risk on the risk register with the team

A senior manager audits your work and decides whether you’re doing a good job

An external auditor reviews the risk response strategies for each risk

An external auditor reviews the project work to make sure the team isn’t introducing a new risk

Exam Answers

-

Sharing is when a project manager figures out a way to use an opportunity to help not just her project but another project or person as well.

Note

It’s OK to share an opportunity with a competitor—that’s a win-win situation.

Answer: D

Collaborating is a conflict resolution technique.

Answer: A

You use an RBS to figure out and organize your risk categories even before you start to identify them. Then you decompose the categories into individual risks as part of Identify Risks.

Answer: B

Your risk register should include watch lists of low-priority risks, and you should review those risks at every status meeting to make sure that none of them have occurred.

Answer: C

The expected monetary value (or EMV) of the weather risk is the probability (30%) times the cost ($12,000), but don’t forget that since it’s a risk, that number should be negative. So its EMV is 30% × –$12,000 = –$3,600. The building materials opportunity has an EMV of 20% × $5,000 = $1,000. Add them up and you get –$3,600 + $1,000 = –$2,600.

Note

When you’re calculating EMV, negative risks give you negative numbers.

Answer: C

Using the Interview technique, experts supply their opinions of risks for your project so that they each get a chance to think about the project.

-

Susan bought an insurance policy to cover cost overruns due to weather. She transferred the risk from her company to the insurance company.

Answer: B

You wouldn’t want to transfer an opportunity to someone else! You always want to find a way to use that opportunity for the good of the project. That’s why the response strategies for opportunities are all about figuring out ways to use the opportunity to improve your project (or another, in the case of sharing).

Note

Wow, did you see that huge red herring?

Answer: B

A secondary risk is a risk that could happen because of your response to another risk.

Answer: D

The processes of Risk Management are organized around creating the risk register, and updating it as part of project documents updates.

Answer: B

Note

The key to this one is to remember that the money the project makes is positive, and the money it will cost is negative.

$200,000 × 0.70 = $140,000 savings, and $100,000 × 0.30 = –$30,000 expenses. Add them together and you get $110,000.

Note

That’s why it’s useful to figure out the EMV for a risk—so you know how big your contingency reserve should be.

Answer: B

Contingency reserves are calculated during Perform Quantitative Risk Analysis based on the risks you’ve identified. You can think of a risk as a “known unknown”—an uncertain event that you know about, but which may not happen—and you can add contingency reserves to your budget in order to handle them. Management reserves are part of Cost Management—you use them to build a reserve into your budget for any unknown events that happen.

Answer: D

Risk monitoring and response is so important that you should go through your risk register at every status meeting!

Answer: D

The Probability and Impact matrix is a tool that you use to analyze risks. You might find it in your Project Management plan, but it’s not included in the risk register.

Answer: A

It’s really important that you get the entire team involved in the Identify Risks process. The more people who look for risks, the more likely it is that you’ll find the ones that will actually occur on your project.

Answer: D

Even though this looks a little wordy, it’s just another EMV question. The probability of the risk is 50%, and the cost is –$650, so multiply the two and you get –$325.

Answer: A

This is just the definition of Monte Carlo analysis. That’s where you use a computer simulation to see what different random probability and impact values do to your project.

Answer: D

There are some risks that you just can’t do anything about. When that happens, you have to accept them. But at least you can warn your stakeholders about the risk, so nobody is caught off guard.

-

You’ve got an unplanned event that’s happened on your project. Is that a risk? No. It’s a project problem, and you need to solve that problem. Your Probability and Impact matrix won’t help, because the probability of this happening is 100%—it’s already happened. No amount of risk planning will prevent or mitigate the risk. And there’s no sense in trying to take preventive actions, because there’s no way you can prevent it. So the best you can do is start looking for a new part supplier.

Answer: C

It’s a good idea to bring in someone from outside of your project to review your risks. The auditor can make sure that each risk response is appropriate and really addresses the root causes of each risk.