In the spring of 1939 four young army officers set off from the Paris Military Academy along the Champs de Mars to begin an arduous motorcycle journey to Dakar, French West Africa’s federal capital.1 Stories of their progress, a precursor to the latter-day Paris-Dakar rally, were celebrated as part of a fortnight-long ‘imperial market fair’ in April. The sights and smells of colonial products helped take Parisian minds off the Nazi menace. Department stores vied with five kilometres of roadside stalls in the city centre that offered exotic commodities for all tastes and pockets. Eager shoppers could buy everything from exquisite African carvings and Malagasy vanilla pods to musky Vietnamese perfumes and leopard-skin coats.2 ‘Buy empire’, a message more familiar to consumers across the English Channel, resounded louder than ever in 1939 as politicians and public in France drew comfort from the reassuring vastness of their colonial assets on the eve of war.3 How far were these hopes realized over the next six years?

For an ‘imperial nation-state’ the challenge of total war was to mould its empire into a strategic asset—a global ‘power system’ as opposed to a disparate agglomeration of territories, peoples, and interests.4 Raw materials and foodstuffs, colonial revenues, strategic bases and, above all else, additional manpower were the hard currency of imperial power in war. Just as important from a social perspective were the greater confidence and common purpose that a united empire might confer. But there was an altogether different construction of empire in a global conflict, one that was overwhelmingly negative. Far-flung colonies, remote naval bases, and other useful prizes were vulnerable and hard to defend. Policy-makers on both sides of the Channel thus came to regard some colonies as hostages to fortune. Imperial resources and attachments might be precious, but the financial and strategic implications of keeping global empires intact against at least two, perhaps three, enemies among the great powers were nightmarish. At the heart of that nightmare were excruciating choices. In the British case, deathly Flanders fields beckoned once more for home and empire forces because only commitment to a continental fight alongside France could protect Britain from Nazi invasion. On the other hand, only by conserving limited military capacity could exposed colonial territories be protected at the same time. The simplest solution—spending more on rearmament in order to meet both European and imperial obligations—was precluded for the sound reason that unrestrained defence expenditure would undermine the one incontestable advantage that Britain retained next to Nazi Germany: sane finances.5

While British strategic planners wrestled with this dilemma, France’s Minister of Colonies Georges Mandel reassured his nation’s anxious radio listeners in the winter of 1939 that their empire’s reserves of people, money, and supplies would save them. The son of a Jewish tailor from Alsace, a territory only re-assimilated into France after 1918, Mandel was a virulent critic of fascism. His faith and his republican patriotism would later cost him his life.6 But in the autumn of 1939 his imperial rhetoric purred reassurance. Unfortunately, it left French service chiefs unconvinced. They worried that the colonies, which Mandel identified as saviours of France, might, in fact, drain vital reserves needed for the looming Wehrmacht onslaught.7 For both imperial powers the actual position after war broke out in Europe lay somewhere between these two positions. Some colonies became warehouses, their food and other raw material exports indispensable. But numerous dependent territories faced new foreign occupations. More serious in the long term, the coercive means employed to mesh local populations into serving imperial war efforts fed antagonism to foreign rule.8 The contradictory messages of wartime imperial propaganda were also unsettling for home audiences. Was Britain a global power or a ‘plucky little island’? Was the fight for freedom a European or a global one? Conscious that their Home Service and forces programming could reach an estimated thirty-three million adults in Britain alone, in September BBC controllers identified the essential challenge of broadcasting propaganda about the colonies: demonstrating ‘that our democratic professions are not a hypocritical pretence’.9

The ways in which Britain and France mobilized their empires to fight World War—and the representation of these efforts at home and overseas—would shape post-war decisions about resisting or accommodating local pressures to decolonize. This chapter reviews these events. It illustrates that in those locations where anti-colonial sentiment was most keenly felt—India, Burma, and Palestine among British territories, Algeria and Vietnam among French ones—the end of the Second World War would be immediately followed by the outbreak of anti-colonial uprisings that heralded decolonization’s first wave.

Britain and France entered the war as allies in the struggle against Nazi Germany; but what about imperially? Franco-British staff talks had been held in London, Beirut, Singapore, and Aden over the summer of 1939 to work out joint regional strategies for the protection of neighbouring imperial territories. These meetings were high on grand schemes: a ‘Balkan front’ alongside Turkey, naval cooperation in the South China Sea, a common defence plan for the Indian Ocean.10 But they were short on tangible results. Turkey, despite signing up to a tripartite alliance with Britain and France on 19 October, stayed out of the war, alarmed by the implications of the August 1939 Nazi–Soviet Pact for its northern frontiers.11 In the Far East French negotiators could offer nothing to tempt British naval planners to venture east of the so-called ‘Malay barrier’ into the waters off Indochina. The discussions held in Singapore during late June had a particularly Never-Never Land quality. French navy representatives confirmed that their government would construct battleship base facilities at Camranh Bay and Saigon but had no battleships to spare. Admiral Sir Percy Noble explained where a British Far Eastern fleet might eventually operate but, as yet, commanded no fleet to speak of.12 Here was ‘imperial overstretch’ writ large in the obvious lack of warships to block hostile incursion.13 It proved easier to pool resources in the Indian Ocean because the British and French naval resources in Aden, Kenya, Djibouti, and Madagascar were relatively small and the threat from Japan more remote.14

This combination of closer Franco-British partnership with limited outcomes was equally apparent in economic affairs. Certain categories of French products were exempted from the import restrictions announced by Neville Chamberlain’s government on the outbreak of war. September 1939 also saw talks begin over fuller commercial integration between the two partners. The French Premier Édouard Daladier declared his support for a system of ‘federal trade’ between the two empires in a high-profile speech to the French Senate on 30 December 1939. Yet, while further discussions on broader inter-imperial economic cooperation got under way in London in January 1940, free trade between British and French territories was never agreed.15 The arrangement which pertained instead for most of the war saw Britain bankroll those French colonies that ‘rallied’ to General de Gaulle’s Free French movement in return for which these territories were subsumed into Britain’s war effort, supplying primary products, mainly foods and minerals, in return for the sterling needed to finance Charles de Gaulle’s nascent government-in-waiting.16

British backing for de Gaulle’s Free French movement reflected the way that France and its Empire splintered after defeat by Germany in June 1940. Part military force, part quasi-government-in-exile, Free France was certainly committed to fighting the Axis Powers, but it operated outside France for most of the war.17 Until mid 1943 its principal strategic assets were in sub-Saharan Africa, President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration blocking de Gaulle’s move northwards to ‘liberated’ Algiers following the American landings in North Africa the previous November.18 The Free French should not to be confused with the diverse civilian resistance networks that sprang up within metropolitan France. Indeed, these homeland resisters vied with Free France for power and influence once the Vichy regime established under Marshal Pétain became more venal and collaborationist from 1941 onwards. Meanwhile, because their movement coalesced around General de Gaulle in London and among his supporters in the colonies, followers of Free France—a politically diverse group of armed forces personnel, politicians, diplomats, bureaucrats, and African colonial troops—were often misleadingly described by the catch-all term ‘Gaullists’.19

For some, support for the General and his unique vision of French greatness—or grandeur—verged on the fanatical. For others, de Gaulle’s attractions were incidental to the more urgent priorities of fighting fascist occupation, ousting Vichy, and restoring republican democracy to France. As for Free France’s colonial troops, who campaigned arduously in North Africa, Italy, and southern France, serving de Gaulle was, initially at least, as much circumstantial as deliberate. For what one historian dubs these ‘soldiers of misfortune’, it usually reflected the location of a particular garrison or the loyalties of its senior officers, not the political leanings of the rank-and-file.20 The estimated 16,500 Free French military losses during campaigning in North Africa and Italy were primarily colonial. Villages in Morocco, Mali, and Algeria, not Brittany, the Ardèche, or the Pas-de-Calais, mourned the largest numbers of soldiers killed in French uniform after June 1940.21

The ambivalence within the Free French movement towards its symbolic figurehead points to other aspects of wartime France that bear emphasis. First, French people and society—at home and overseas—were as much politically as physically divided by the 1940 collapse. The circumstances of the defeat, the massive population exodus that preceded it, the removal of at least 1.65 million French prisoners of war (POWs) to Germany, and the carving of mainland France into occupied and unoccupied ‘zones’ turned people’s worlds upside down.22 The French population experienced warfare fitfully, first in May–June 1940, then following the Allied landings in northern and southern France in June and August 1944. In between-times their experiences of violence and loss derived from the consequences of occupation and population displacement. The absence of so many POWs, later compounded by German recruitment of 840,000 forced labourers, plus the forced enlistment of young men from Alsace into the Wehrmacht, weighed heavily. Worst of all, French Jews were systematically wiped out in the manner of their co-religionists and other persecuted groups in Eastern Europe.23 Another cruel irony was that allied bombing killed so many French civilians, the 600,000 tons of British and American bombs dropped on France resulting in an estimated 60,000 civilian deaths, a figure broadly comparable to the number of Britons killed in German raids on the United Kingdom.24

The Vichy state took shape amidst the chaos. Its authority was confirmed by National Assembly parliamentarians who obligingly voted themselves out of office—and the Third Republic out of existence—by an overwhelming majority of 569 to 80 on 10 July 1940. Granted full powers by this act of political hari-kiri, the innate authoritarianism of Marshal Pétain’s regime was set free at home and in the colonies.25

Vichy signified what American historian Stanley Hoffman memorably dubbed ‘the revenge of the minorities’. Right-wing anti-republicans, Catholic traditionalists, and proto-fascists, the outsiders of the pre-war political system, moved to centre-stage.26 In a sweetly ironic twist, the regime’s improvised Ministry of Colonies took up residence in Vichy’s Hotel Britannique.27 It is doubtful whether many French citizens or colonial subjects immediately grasped the implications of France’s ideological lurch to the extreme right. Their lives thrown into confusion, the dominant emotion among the domestic population was bewilderment. Missing relatives, shortages, and black market iniquities generated greater anxiety than high politics.28

Those prepared to express firm convictions or adopt life-changing positions for or against Vichy were a small minority. Some were ideologically motivated, welcoming the opportunity to build a disciplined and hierarchical society shorn of what they considered the decadent excesses of republican liberality.29 Others felt compelled to keep fighting by the very opposite political and ethical values. Pre-eminent among them were Communists. Their party outlawed back in September 1939, a month after Stalin’s signature of the Nazi–Soviet Pact, Communist supporters were driven underground well before the 1940 defeat.30 If resistance organization came naturally to Communist activists, still others were animated by patriotic resolve, by personal loss, or, as in the case of numerous Jewish families, by an ethno-religious background that placed them in mortal danger.31 Settler communities in the empire, most with family or military connections ‘back home’, were also shattered by the defeat. But they had greater scope to express opinions than their kith and kin in France. Although their attachments were commensurately diverse, a high proportion welcomed Vichy’s authoritarian machismo, which came with a pronounced racist tinge that celebrated settler virility and identified authentic French identity with whiteness.32

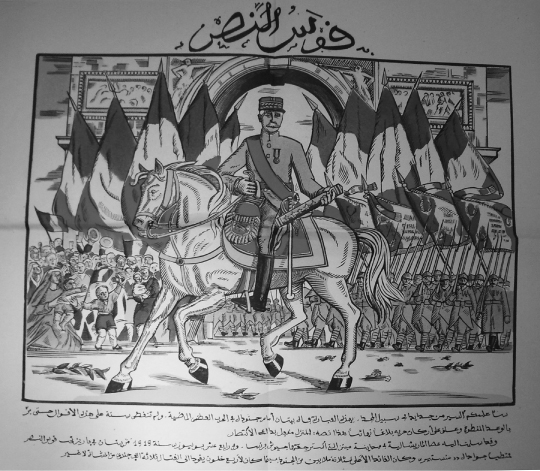

Figure 4. Marshal Pétain appears as Napoleonic saviour in this Vichy propaganda poster produced for dissemination in French North Africa.

Another point, then, is that colonial communities, marginal to pre-war French politics, were more intimately involved in the wartime struggle over France’s long-term destiny. The consequences were acutely divisive. For much of the Second World War, combat within colonial territory was Franco-French, part of an undeclared civil war between Vichy and its domestic enemies. Measured by the objectives of its principal combatants, this colonial civil war was about the future of France and was not colonial at all. Yet this internecine struggle was fought in the midst of colonial subjects and frequently exploited them to do the actual fighting. The line between voluntary military contribution and coercive recruitment of colonial soldiers was sometimes impossible to trace. Even so, the Franco–French struggle remained curiously removed from the daily lives of colonial communities for whom more fundamental questions of food supply, employment, and basic rights figured larger.33 Not so for the French Empire’s white populations. Even when the wider war impinged on them, as, for instance, when Japanese forces occupied southern Indochina in 1941, or when US and British (including imperial and other Allied) forces fought to expel Erwin Rommel’s army from French North Africa in 1942–3, the quarrels between Vichy supporters and their resistance opponents predominated in French minds and actions. This raises a final point. For the uncomfortable fact confronting all sides in this French civil war was their de facto reliance on stronger external backers. Vichy existed only as long as it was expedient for Nazi Germany to leave Pétain’s regime in place, not just in unoccupied southern France, but in much of French Africa as well. And the Free French movement, as well as the internal resistance groups fighting Vichy and its German and Italian overseers, were themselves dependent on some type of Allied support: Anglo-American facilities, money, and war materiel for some; Soviet ideological inspiration for others. The upshot was that France’s wartime faction fights, although substantially played out in colonial theatres, were peculiarly skewed towards a domestic struggle for power. Phrased differently, empire provided the terrain but not the agenda for the French leadership contest fought out between 1940 and 1945.

The British Empire, of course, was also fighting for its existence, a fact that left no room for sentiment about the fate of former allies. British naval bombardment of the largest component of the French Mediterranean fleet at anchor in the Algerian port of Mers el-Kébir in July 1940 drove the point home. Intended to nullify the risk of the French vessels falling into Axis hands, Royal Navy shelling killed 1,297 French sailors. Their commanders had rejected British entreaties to come over for two reasons above all. One was that remaining in North Africa seemed essential to keep the French Empire intact after the armistice. The other was that, alongside the Empire, an operational fleet was the only strategic card remaining to a France in defeat. These reasons seemed justification enough to ignore the ultimatum to surrender the ships into British hands or face bombardment, a fatal mistake.

The inevitable cries of Perfidious Albion went up loudest among senior French naval commanders, already seething over Britain’s ingratitude for the French maritime cover provided for British troops evacuating from Dunkirk. What Churchill portrayed as a remarkable combination of British improvisation and courage was viewed rather differently from a French perspective: as an indecently premature retreat only accomplished thanks to the French Navy. Furthermore, France’s naval leaders had pledged after the Franco-German armistice to scupper their ships rather than cede them to Germany. And they later proved their word by sinking their remaining warships in Toulon harbour after German forces overran unoccupied Vichy France in November 1942. The loss of so many lives at Mers el-Kébir added injury to insult.34 Most galling of all to Vichy’s new politico-naval elite was that Britain, which had so recently relied on French military strength to protect its home islands from German attack, rounded on France in its most agonizing hour of need.35 Their anger had longer-term implications. Several French Admirals—Jean-Marie Abrail, Jean Decoux, Jean-Pierre Esteva, Charles Platon and, of course, Darlan—rose to prominence as ministers and colonial governors under Vichy. This made the task of persuading French colonial administrations from North Africa to Indochina to join the allied cause all but impossible.36

As the Mers el-Kébir attack indicates, after the fall of France British military engagements took a more desperate turn. The British Empire’s war thereafter was one of paradoxes, revealing the best and the worst of imperial connections. Dominion engagement was for the most part willingly offered. Only Éire chose neutrality, although Afrikaner opinion in South Africa favoured it as well.37 Once committed, every Dominion provided invaluable support. Even neutral Ireland contributed 43,000 volunteer servicemen and women. Army divisions from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Southern Rhodesia helped expel Italian forces from East Africa in 1940–1 before joining the North African campaign against Rommel’s Afrika Korps during 1940–3. Dominion accents could also be heard throughout the wider Mediterranean theatre from the defence of British Egypt and the ill-fated landings in Crete in May 1941 to the attack on Vichy French Syria two months later and the invasion of Italy over the summer of 1943. Australians and New Zealanders also fought in the Pacific War, where, inexorably, they came under the wing of an American war effort that eclipsed the remaining British presence in the region.38

Some young Australians also followed the fortunes of France with particular interest. A Melbourne High School pupil recalled that the war was brought to life in French lessons when Le Courier australien, a fervently pro-de Gaulle weekly published by the country’s tiny French community, recounted the latest acts of derring-do by the General’s followers.39 Schoolboys enthralled by de Gaulle were one thing, but most Australians were more animated by decisions taken in their name in London. Three factors sapped Australians’ and New Zealanders’ belief in British capacity to sustain a global, fighting role. First were the crushing imperial defeats experienced in the opening weeks of war against Japan. The collapse of the Far Eastern garrisons of Hong Kong and Singapore between December 1941 and mid-February 1942 were seared into popular memory by press reportage of the killings, rapes, and internments that accompanied them.40 These calamities underscored the failure of Britain’s limited attempt to enforce a naval perimeter around its East Asian possessions. As we have seen, inter-war plans to send a ‘main fleet’ to Singapore withered by 1939 as the German and Italian threats loomed larger.41 The improvised naval force eventually dispatched met a tragic end. Repulse and the Prince of Wales, the only two British battleships sent to patrol the South China Sea, were sunk by nine Japanese bombers off the Malayan coast on 10 December 1941. There was a macabre echo of Mers el-Kébir here: the lethal bomber squadron took off from a Japanese-occupied airbase in French Vietnam.

These disastrous British defeats on land and sea left the Australasian Dominions without effective protection. Churchill, ‘stupefied’ by the news according to his doctor, Lord Moran, made no attempt to portray the garrison’s surrender as anything less than an imperial disaster. Even in New Zealand, always characterized as the most loyal, unflappable Dominion, there were understandable signs of public anxiety born of a dawning recognition of powerlessness.42 Australia’s Labour Prime Minister John Curtin recalled his country’s two army divisions home, rejecting their assignment to active theatres, particularly in the Middle East and Mediterranean, remote from the more present dangers in Australia’s Near North. The sense that Britain disposed of Australasian men and materiel without providing tangible insurance in return became a second source of disillusionment. Incontrovertible evidence of British dependence on American support in Asia added the third dimension to this crisis of confidence, contributing to what one historian describes as Australia’s ‘dedominionization’.43

It was Canada, however, that made the most decisive Dominion contribution to the British Empire’s struggle for survival.44 Although the Ottawa Parliament convened to discuss it, Canada’s entry to war alongside Britain was, in John Darwin’s words, ‘the merest formality’.45 Shaky French Canadian support had been bolstered some months earlier, principally by Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s pledge that conscription would be avoided. This was a promise he could not keep. Pushed by popular demand in English-speaking Canada, Mackenzie King’s government eventually conceded a referendum on conscription in April 1942. The result revealed a nation still sharply divided along linguistic lines with 83 per cent of English Canadian voters supporting the measure and 72.9 per cent of French Canadians opposing it.46 In late 1939, however, these ethno-regional cracks were papered over well enough and by December Canadian troops were stationed in Britain. Indeed, Canada should be acknowledged for what it was: not just one of many cogs in an imperial wheel but a major ally in its own right. Justifiable Canadian sensibilities about equal treatment in dealings with Britain were appeased, mostly by Chief of Imperial General Staff Sir Alan Brooke. It fell to him to placate two highly political Canadian Army commanders: Generals Andy McNaughton and Harry Crerar. Brooke enjoyed several advantages in doing so. Among them were common patterns of Anglo-Canadian training and military doctrine, plus a shared commitment to fight together, even in integrated formations.47

Over 85 per cent of the 1,086,771 male and female service personnel from Britain’s oldest Dominion were volunteers. So many passed through Britain that the BBC Forces Programme began airing ice hockey highlights on Sunday evenings.48 Many were lost in dreadful circumstances—as members of the isolated Hong Kong garrison that surrendered to a rapacious Japanese assault on Christmas Day 1941; as the hapless assault brigade cut down during the August 1942 Dieppe Raid.49 It was Canada that dominated the Commonwealth Air Training Scheme, providing vital replenishment to the service arm that suffered the largest proportionate share of frontline losses. And, owing to the circumstances of their deployment, relatively large numbers of Canadian service personnel became POWs. One of those captured was Captain Lionel Massey, son of Vincent Massey, Canada’s High Commissioner in London, who helped devise Britain’s POW policies.50 The Royal Canadian Navy was also integral to the North Atlantic convoy system, which was fundamental to Britain’s capacity to fight on. Finally, Canada manufactured more and lent more than its smaller Dominion cousins, facts which confirmed that the old asymmetries of Anglo-Canadian—and Anglo-Dominion—relations were changing.51

India’s contribution to Britain’s war effort was larger still in human terms but its involvement in the war—demanded, rather than requested by Viceroy Lord Linlithgow in September 1939—exposed the fallacy of British claims to fair and equal treatment of its subjects overseas.52 The All-India National Congress, although internally divided over its attitude to the war, was uniformly outraged at Britain’s short-term rejection of constitutional reform. Congress representatives promptly resigned from seven of India’s eleven provincial governments.53 As Yasmin Khan has suggested, India occupied a liminal space, an uncomfortable, median position between loyal imperial home front and restive, quasi-war zone. It was certainly a place where decolonization beckoned.54 Little wonder that signs of disaffection proliferated among Indian army divisions stationed in Singapore and Hong Kong before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Soldiers’ sense of being taken for granted was sharpened by the limited results of long-promised ‘Indianization’ of officer and NCO positions in Indian Army units. Not surprisingly expatriate Indian nationalists and the Japanese military found enthusiastic recruits for the anti-British Indian National Army among the thousands of Sepoys taken prisoner during Japan’s unstoppable progress through Malaya to Singapore in January–February 1942.55

Almost as damaging as the 32,000 or so Indian troops who agreed to take up arms against the British Empire were the million-plus Indian migrants who lived in Burma where they formed the majority ethnic group in the capital, Rangoon. By May 1942 over 300,000 Indian refugees had arrived in Calcutta (Kolkata), the teeming cultural hub of Bengal. Most arrived destitute from the Burmese port of Chittagong. With every disembarkation, the refugees’ harrowing stories of Japanese cruelty and British disarray sent rumour and panic pulsing throughout north-eastern India. The plight of these migrants confirmed that the early stages of the Pacific War caught the British looking the wrong way, too preoccupied with the Mediterranean theatre and colonial India’s north-west frontier and not enough with the encroaching menace from the East.56 Matters quickly went from bad to catastrophic. On 8 August 1942 Congress told Britain to ‘Quit India’, inspiring a nationwide movement in support of the call. War Cabinet approval for the arrest of Gandhi and other Congress leaders a month later heralded a vicious police crackdown.57 Perhaps because assignments to India were liable to involve such repressive policing, military postings there were considered unglamorous and insalubrious. Although the regulation of intimate contacts between British and Allied troops became an increasing official obsession, the sexual exploitation of local women remained prevalent.58 Venereal disease among British imperial troops garrisoned in Indian cantonments reached almost fifty per thousand by 1945—the highest rate in any British military theatre.59

Other colonial peoples made proportionately large sacrifices in defence of the Empire, whether eagerly or not. In their cases the discomfiting juxtaposition between imperial patriotism and the empire’s structural racism was even harder to ignore. Black African troops fought Italians in Ethiopia and Japanese in Burma, but still in white-officered colonial units. The colour bar that prevented non-white service personnel from becoming officers was formally relinquished in October 1939. But its spirit lived on. To avoid ‘cross-contamination’, even military blood banks kept separate stocks for whites and non-whites. Young men from the British Caribbean, West Africa, and the Indian subcontinent eager to take to the skies had to wait until bomber command became truly desperate for replacement air-crew before they could do so.60 Discriminatory treatment was just as stark beyond the armed forces. Forced labour, which had been nominally abolished in the British, if not the French, Empire at the behest of the International Labour Organization in 1930, reappeared in several sub-Saharan colonies. Coercing labour from wider swathes of the African civilian population was impelled by the war’s insatiable demand for strategic war materiel and foodstuffs like Nigerian tin or Tanganyika’s agricultural produce. And thousands of colonial sailors from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean flocked to Britain’s merchant navy in which an estimated 5,000 died (about a sixth of total merchant navy losses). Many worked below decks as boiler-room stokers, the location notorious among seamen as the most lethal in any submarine attack.61

Ashore in Britain’s ports, some of these seamen faced other humiliations. So did the colonial war workers serving Britain’s armaments industry. Where Merseyside was once remarkable for its relatively low incidence of overtly anti-black sentiment, racist attacks on West Indian munitions workers in Liverpool mounted once large numbers of American GIs began transiting through the city from 1942 onwards. The city’s hotels, dancehalls, and pubs began closing their doors to Jamaicans and others, probably aware of the injustice involved, but reluctant to risk losing GI trade. Responding to the rising incidence of racial violence in British port cities, in September 1942 the Colonial Office even toyed with the idea of requiring black colonial war workers in Britain to wear a badge ‘so they can be easily differentiated’. Thankfully, the proposal was soon abandoned.62

Disintegration of the French Empire continued inexorably over three wartime stages. From the Phoney War, through Vichy dominance in 1940–2, to the Free French ascendency cemented by de Gaulle’s triumphal return to Paris on 25 August 1944, life remained very hard for colonial subjects. The three stages thus shared one point in common despite the fact that French political leadership differed in each one. Throughout the war years, economic hardship, typified by foodstuff shortages and chronic price inflation, matched social exclusion and political repression in bearing more heavily on colonial lives than the progress of allied campaigns or changes at the top of the colonial tree.

French North Africa is a case in point. Typically discussed in relation to the aftermath of French defeat in 1940 as well as in terms of the outcome of Operation Torch, the French-ruled Maghreb was convulsed by other pressures entirely. From the economic impact of conscription in autumn 1939 through the foodstuff crises and urban public health scares that sapped French capacity to overcome the material consequences of metropolitan defeat, French North Africa’s war looked very different to the local administrators and wider populations that lived through it. Viewed in this way, the war years were most notable for the irreversible damage they wrought to economic stability and the hierarchies of colonial rule in North Africa. By the time General Maxime Weygand took over as Algeria’s Governor-General on 17 July 1941 French North Africa’s economic fortunes had declined precipitately. Fuel and foodstuffs were in short supply, the agricultural economy was profoundly disrupted, and average wages languished at subsistence level.63

For all that, economic crises and limited sovereignty proved no barrier to the embrace of Vichy’s ‘National Revolution’ by colonial regimes enthused by the Pétainist cults of xenophobic ultra-nationalism, stricter social hierarchies, and a rural nostalgia flavoured with Catholic pro-natalism.64 Peasant values, large families, and veneration of conservative, often anti-republican institutions—the Catholic Church and the military foremost among them—came naturally to settlers and authoritarian administrators. Thus we find Jean Decoux, another Admiral catapulted to political prominence as Vichy’s Governor of Indochina, promoting Pétainist youth movements in French Vietnam, celebrating the cult of Joan of Arc (Vichy’s preferred symbol of patriotic self-sacrifice), and lauding the ‘magnificent’ fecundity of a settler couple from Tonkin whose twelve children holidayed near the Governor’s Palace in the Vietnamese hill station of Dalat.65 The air of detachment from reality was hardly surprising when the realities in question were so alarming: the dual menace of a Japanese takeover and an incipient Vietnamese revolution impelled by French inability to satisfy the most basic needs of Indochina’s peoples—for security and food.66

Across the French political divide, it is easier to see why the senior Gaullists in London were determined to exploit the colonies when one remembers how few cards they had to play with their British patrons. And the British mission to the Free French National Committee was more than an intermediary. Not only did it relay Gaullist economic requests for funds, supplies, shipping, and other transport to the War Cabinet, it also filtered out such demands when they conflicted with the overarching priorities of the Anglo-American supply boards that controlled the circulation of goods between allied and imperial territories.67

Furthermore, British officialdom’s enduring scepticism about de Gaulle and Free France as rulers of a revitalized French Empire was writ much larger across the Atlantic.68 In February 1942 Maurice Dejean, foreign affairs commissioner in the French National Committee, articulated a widely-held view among Gaullist staff about the underlying reason behind the Roosevelt administration’s enduring coolness towards Free France. The answer, Dejean insisted, lay in a secret US-Vichy deal whereby Marshal Pétain’s regime agreed to minimize strategic concessions to Germany provided that the United States left Vichy’s empire alone. US recognition of de Gaulle was allegedly withheld as part of the bargain.69 The simpler reason for Washington’s derision of Free France was that Roosevelt loathed de Gaulle, a man he considered pompous, autocratic, and selfish.70 But Dejean’s conspiracy theory was less outlandish than it seemed. Roosevelt’s special envoy, Robert Murphy, agreed with Admiral Darlan in March 1941 to trade US foodstuff convoys to Vichy for the promise (quickly broken) to limit collaboration with Germany, particularly in North Africa.71 Murphy’s talks marked the beginning of a longer-term association that climaxed in the so-called ‘Darlan deal’. It left Vichy’s former premier at the head of government in Algiers in return for the regime’s acquiescence in Operation Torch, the US takeover in Morocco and Algeria after only seventy-two hours of fighting in November 1942.72

De Gaulle’s supporters were incandescent, although far from surprised. Adrien Tixier and Pierre Mendès France, later ministers in the post-war Fourth Republic, spent their war years in Washington trying to win support for the General. By mid 1942 both men were at the end of their tether. The Americans did not understand what Free France stood for, they were hopelessly naive about the Vichy regime, and Roosevelt simply followed his instincts most of the time.73 In late August, after the US State Department once again refused to recognize the Free French movement as the legitimate voice of France, Dejean let rip again:

American policy continues to be the result of several diverse factors: wild romanticism, brutal materialism, economic imperialism, anti-colonialism, anti-British and anti-Russian tendencies, Machiavellianism and puerility, the whole lot combining into something Messianic and unconsciously sure of itself.74

Excluded from Torch planning, de Gaulle was even more incensed by American support of his new rival for leadership of the Free French, General Henri Giraud, in the limited handover of power that followed Darlan’s assassination in Algiers on 24 December 1942.75 The mutual incomprehension that characterized the Roosevelt–de Gaulle relationship only deepened when they met for the first time at the inter-allied conference in Casablanca in January 1943. Side-lined during the summit, de Gaulle’s attitude went from frosty to glacial as he watched the Americans fete the rather wooden and politically obtuse Giraud.76 When de Gaulle eventually came face to face with Roosevelt, members of the President’s secret service detail hid behind the meeting-room curtains, their tommy guns poised.77 Hardly the beginning of a thaw.

Operation Torch also cast a spotlight on the changing economic balance of power in the Maghreb as the US invasion force moved rapidly eastwards. Its supply needs took precedence over all else and the Americans’ dollar purchasing power placed the French North African franc under strain. After Torch, the Algiers authorities quickly negotiated a provisional franc–dollar exchange rate with the US Treasury Department. This was, in turn, supplanted at the Casablanca conference by a stabilization accord that pegged the value of the franc throughout French Africa at fifty to the dollar.78 Although the greater price stability that resulted was welcome to North Africans, the Casablanca economic agreements did not curb the overweening power of a local black market in which dollars reigned supreme to the detriment of rural consumers least able to obtain them.79

It was no coincidence that, during the 1943–4 hiatus of transfers of executive power between Vichy and Free French administrations, the founding statutes of leading nationalist groups, including Algeria’s Amis du Manifeste et de la Liberté and Morocco’s Istiqlal (Independence) movement cited poverty and economic exploitation as justifications for their anti-colonial platforms.80 Likewise, Messali Hadj’s Parti du Peuple Algérien, still the major force in Algerian domestic politics despite being banned outright since 1939, insisted that any ideological differences between Vichy and Gaullist leaders were eclipsed by their shared colonialism, a phenomenon epitomized by ruthless wartime economic extraction. Whether Algeria’s foodstuffs, minerals, and other primary products were shipped to Marseilles and thence to Germany or to Allied ports, the essential fact was that Algerians, denied any democratic choice over participation in the war, went hungry. Messali received a fifteen-year sentence of forced labour from a Vichy military tribunal on 28 March 1941. So he might have been expected to welcome the advent of a Gaullist provisional government in Algiers, the French Committee of National Liberation (FCNL).81 The nomenclature was telling. As Messali asked FCNL members on 11 October 1943, why should Algerians support French liberation when their own national freedom was denied?82

Meanwhile, to the east, US forces moved into Tunisia over the winter of 1942–3. Local sections of the country’s dominant nationalist group, Néo-Destour (the ‘new constitution’ party) had been denuded by police harassment and long prison terms. Hoping that the party leader Habib Bourguiba and his followers would repudiate their erstwhile French persecutors the German authorities freed the Néo-Destour executive in January 1943. They were disappointed. Bourguiba denounced the Nazi occupation of Tunisia, thinking that his bravery might be rewarded by de Gaulle’s followers. This, too, proved a vain hope. Repression of nationalist activity resumed once Rommel’s forces were evicted. During 1944 the Free French re-imposed the ban on Bourguiba’s party and ignored Tunisia’s status as a protectorate with its own monarchical administration by enacting legislation that centralized political power under French authority. This signalled the beginning of Bourguiba’s turn away from France towards the cultivation of Arab and US opinion, a strategy pursued until Tunisia achieved its independence in March 1956.83

North Africa’s political violence in 1944 was gravest in Morocco. The ill-advised FCNL decision to arrest the four leaders of the Hizb el-Istiqlal, Morocco’s foremost nationalist voice, on 29 January provoked rioting in Rabat, Salé, and Fez, the death of at least forty protesters, and the arrest of over 1,800 more.84 As urban disorder became endemic in Morocco even the Algiers authorities admitted that supply problems, iniquitous rationing, and consequent shortages had become inseparable from nationalist dissent.85 Perhaps inevitably, the nature and scale of Maghribi recruitment to the First French Army, which was meanwhile fighting northwards through Italy, Corsica, and southern France, deepened the animosity between the Gaullist imperial establishment and their nationalist opponents. To the former, these units confirmed the unity of purpose between France and its North African subjects, although the army’s cadres were progressively ‘whitened’ the closer they got to the French capital. To the latter, the large numbers of North African army volunteers merely indicated how desperate they were for a steady income.86 And it was a different story for Algerian conscripts among whom desertion rates climbed towards twenty per cent by July 1943 with some 11,119 out of 56,455 avoiding the call-up over the preceding six months.87

The Free French were hard-pressed to conceal the signs of unrest in their newly-consolidated African empire. But the breakdown of colonial authority went furthest in the Indochina federation. Admiral Decoux’s faltering pro-Vichy government was isolated and broke.88 It was also threatened from three sides. For General Tsuchihashi’s Japanese military administration the bureaucratic convenience of leaving a bankrupt colonial regime in place became questionable.89 For the regime’s internal opponents, many of them loosely connected in a Communist-dominated coalition called the Vietminh, the implosion of French colonial authority enhanced the prospects for a rapid seizure of power. Finally, for the Americans it made sense to work with Vietminh guerrillas, the sole group capable of mounting any serious local challenge to the Japanese.90

None of these three alternatives appealed to de Gaulle’s supporters, of course. Without the resources to intervene independently in Indochina and unable to ‘turn’ Decoux’s government their way, de Gaulle’s provisional government newly installed in liberated Paris could do little.91 Observing the situation in Vietnam, the Gaullist military attaché in Nationalist China conceded that the Indochina Federation had become ‘a no man’s land’ for the major allied powers. None dared intervene decisively lest they antagonize one another or, far worse, trigger the Japanese takeover they all feared.92 It was the Vietnamese who seized the initiative. By December 1944 Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap, the Vietminh’s leading strategic thinkers, had established the National Liberation Army of Vietnam, which operated from ‘free zones’ in the far north.93 Choosing to overlook the Vietminh’s ideological leanings, the US and British special services—the OSS and SOE—offered training and equipment for sabotage attacks on the Japanese.

Three months later the Japanese struck back. The American re-conquest of the Philippines in early 1945 had alerted Japan’s Supreme War Council to the possibility of similar US amphibious landings in Indochina. These might be supported, not just by the Vietminh but by Decoux’s government as well. Tokyo therefore presented the Governor with an ultimatum: place his administration and the French colonial garrison under Japanese command or face the consequences. Decoux’s ‘non’ spelt the end of French rule—albeit temporarily. Japanese units swept through Hanoi on the night of 9 March, killing scores of French bureaucrats and troops, and interning those unable to make a fighting retreat northwards to China.94 A puppet regime under Emperor Bao Dai was set up in Hue, Vietnam’s imperial capital. Parallel monarchical regimes were re-established in Laos and Cambodia, which reverted to its pre-colonial title of Kampuchea. All three promptly declared ‘independence’ from France under the approving gaze of General Tsuchihashi’s occupation forces. From taxation systems to school curricula, symbols of French colonial power were hastily removed. Kampuchea’s Prince Norodom Sihanouk even restored the Buddhist calendar and urged his subjects to abandon the use of Romanized script.95

The limits to this independence soon became tragically apparent in northern Vietnam where the new authorities under Premier Tran Trong Kim could not prevent heightened Japanese requisitioning, which destabilized the local rice market. Chronic price inflation made food of any kind unaffordable for the poorest labourers and their families. Famine took hold. It was especially devastating in the Red River Delta and two densely-populated provinces of northern Annam.96 Village populations collapsed. Some locked their doors, resolved to die together as a family. Others became famine refugees begging on the streets of local towns and cities. One Hanoi resident described the scene: ‘Sounds of crying as at a funeral. Elderly twisted women, naked kids huddled against the wall or lying inside a mat, fathers and children prostrate along the road, corpses hunched up like foetuses, an arm thrust out as if to threaten’.97

Starvation dominated North Vietnamese politics by early 1945. The faction fighting among the French colonial rulers was at best an irrelevance, at worst an act of shocking insensitivity. Not surprisingly, the combination of Japan’s military coup and the tragic shortcomings of its new surrogate authorities in Indochina enhanced the Vietminh’s legitimacy as a popular resistance movement. For the Western Allies, impatient to secure victory over Japan, as for Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians facing Japanese exactions and resultant food shortages, the Vietminh counted for more than the French as spring turned to summer 1945.

By 1943 Britain had its own colonial insurgents to worry about from the Indian National Army to the Communist-influenced anti-Japanese resistance groups in Burma and Malaya. Nevertheless, growing confidence in eventual allied victory fed renewed bureaucratic interest in the mechanics of colonial administration and the empire’s economic potential. The BBC mirrored the trend, increasing its empire-related output and encouraging wireless listeners to ‘Brush Up your Empire’.98 Politicians’ involvement in post-war planning for empire was, by contrast, minimal. Knocking Italy out of the war, preparations for D-Day, and the uncomfortable fact of Japan’s continued occupation of Southeast Asia confined colonial forward-thinking to the back-burner for Cabinet Ministers.99 Not so for the large numbers of Colonial Office civil servants frustrated by the fact that the War had placed legal reforms, industrialization projects, and constitutional redesign in cold storage.100 Closely attuned to the war’s insatiable appetite for manpower, food, and raw materials, managing empire became more centralized and technocratic even so.101

Colonies’ sterling balances (in other words, British war debts to colonial creditors such as India) were managed from London.102 Government Marketing Boards brought unprecedented regulation to colonial economies in their quest to increase export production. Whitehall departments previously tangential to imperial policy—the Board of Trade and Ministry of Supply, for instance—were now at its heart.103 Grandly-named ‘Resident-Ministers’ (Harold Macmillan among them) were appointed to help manage strategic priorities across vast regions—the Middle East, North, and West Africa. Scientific research was enlisted to help solve problems of development.104 Even missionaries were depicted as adjuncts to government—educators and institution-builders rather than quixotic pioneers.105 Despite this more complex bureaucracy, indeed, perhaps because of it, running the wartime empire was superficially depoliticized. Numerous confrontations of the immediate pre-war years, such as violent clashes between colonial business and organized labour in the British Caribbean or contested partition in Palestine, were treated as if in suspended animation.

This impression of stasis was profoundly misleading. Past imperial problems were, at best, deferred; at worst, they were complicated by unforeseen wartime pressures. Take British East Africa, where unprecedented British governmental interest in the region’s agricultural output brought mixed consequences for local populations. In Kenya, African farmers had already been encouraged to produce more during the depression years. The war brought a host of new restrictions for Kenya’s producers and consumers, even famine conditions for the poorest. At the same time, rising food costs nourished a burgeoning black market. For Africans living as squatters on settler farms in the Kenyan highlands—later, an epicentre of the Mau Mau rebellion—the war brought a reprieve from threatened eviction under the 1937 Resident Native Labour Ordinance. Wartime demand for farm labour and the food grown on squatters’ smallholdings allowed them to consolidate their presence on the margins of settler farmland. Now a more permanent fixture, antagonism between the squatters and their settler employers emerged stronger after the war.106

In the Far East, from Malaya and Singapore to Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Burma, colonial politics were partly conditioned by seismic economic changes, partly by local responses to the Japanese occupier. Meanwhile, in London, members of the ‘Malaya Planning Unit’, what Tim Harper wryly describes as ‘a kind of court in exile’, took the war as an opportunity for a fundamental redefinition of the purpose and scope of colonial governance. Central to this was ‘a general belief that the fall of Malaya, and reports of local “collaboration” with the Japanese, represented the failure of colonial government to secure the allegiance of the subject populations’.107 The pre-war system of ‘government by advice’, it was suggested, was too narrowly focused on cultivating relations with Malay elites.108 Malaya’s Chinese and Indian immigrant populations, many of whom laboured in mines, on rubber plantations, and in agriculture, lacked any representation or investment in British colonial rule. As Harper suggests, the wartime schemes for Malaya’s post-war renovation signified ‘an attempt to replace the confused loyalties of the pre-war period with a sense of allegiance to the colonial state’.109 In March 1942, weeks after the fall of Singapore, the sociological organization Mass Observation, well known for its public opinion surveys, found echoes of this Whitehall reformism in a widespread ‘guilt feeling about the way Empire has been acquired, and the way the colonies have been administered’. Few people levelled specific criticisms against particular policies, but many felt ‘bad’ about the old ways of British imperialism.110

Was it too late to make amends? In British India, British attempts to defuse anti-colonial sentiment by invoking wartime imperial unity were not very successful. The impetus for reform generated by Congress in the late 1930s was too powerful to ignore. Several Ministers in Churchill’s coalition were keen to respond, dismissing their prime minister’s unbending defence of the Raj as ethically indefensible.111 One such was Stafford Cripps. Credited with helping to bring Soviet Russia into the war as Churchill’s Ambassador to Moscow, Cripps joined the War Cabinet as Lord Privy Seal in early 1942. Once in government, he rode a surging wave of public support for greater concessions to India in recognition of the country’s sacrifices in the fight against Japan. George Orwell got it right in describing the resultant ‘Cripps Mission’ to restart negotiations with Indian leaders as ‘a bubble blown by popular discontent’.112

Cripps and his close-knit advisory team—dubbed ‘the Crippery’—spent three energetic weeks roaming India in March and April 1942 trying to coax Congress and the All-India Muslim League into government as members of the Viceroy’s Executive Council. The Cripps Mission stopped short of any formal offer of independence, postponing detailed consideration of British withdrawal until after the war. Gandhi’s famous repudiation of Cripps’ proposals as a ‘post-dated cheque’ from a failing bank was harsh even so. Through sheer persistence, Cripps almost secured an agreement despite the manifest reluctance of Gandhi, Churchill, and Lord Linlithgow to contemplate one. Defence cooperation was one stumbling block, the future status of India’s Princely States another. As historian Nicholas Owen observes, ‘Weakened by the feeble support of Labour for Congress and of Congress for the war, the Cripps Offer could never have taken the weight that each side wished to put on it. Although they did more, Churchill and Linlithgow had merely to point this out.’ Moreover, at the heart of that offer was the pledge that individual Indian provinces could opt out of an Indian Union if they disliked the constitution to be drawn up by a constituent assembly. Gandhi was horrified, considering this tantamount to inviting the Muslim League to press its March 1940 demand for an independent Pakistan.113

The Cripps Mission may have failed, but it was hugely significant, conceding the principle of Indian-run Cabinet government several years before the final talks on British withdrawal began.114 The propensity to flight was clear, albeit temporarily thwarted. The negotiation process was further stalled by India’s worsening political violence and appalling British mismanagement of the country’s internal foodstuff market, which brought famine and massive loss of life to Bengal after 1943.115 By the end of the war, up to three million Bengalis had died of malnourishment and related diseases, a direct result of the ruthless extraction of Indian resources to serve Britain’s war effort.116 Failure to guarantee enough food, perhaps the ultimate symbol of state failure in the Indian sub-continent, delegitimized British rule as surely as the collapse of social solidarity among Bengal’s starving population redoubled Gandhi and other Congress leaders’ determination to build greater national cohesion among India’s poor.117

The Bengal famine stands as a dreadful reminder of the horrors that unremitting prioritization of an imperial mother-country’s needs could cause.118 Yet it was the technocratic, economic turn in wartime colonial administration that underpinned the re-conceptualization of relations between Britain and its colonies immediately after the war.119 After years spent devising elaborate schemes for the empire’s post-war constitutional and social renovation, financial imperatives dominated imperial policy-making by 1945. Consistent with Labour’s thumping electoral victory in the July 1945 general election, the imperialist luminaries, many of aristocratic descent, who once set the agenda for parliamentary, City, and press discussion about Britain’s imperial future, were eclipsed by a younger generation of administrators. Less colourful, if better qualified, what excited them were infrastructure projects and heightened agricultural productivity, not appeals to Britain’s imperial destiny. Lord Hailey’s espousal of pragmatic colonial development was back in vogue.120 This shift in British imperial governance mirrored the new age of austerity. Amidst harsh post-war rationing, statistics on dollar purchases of Malayan rubber and Colonial Office estimates of the potential for expanded peanut production in Tanganyika figured large in Cabinet discussion.121 John Maynard Keynes captured the reason for this triumph of the accountants over the romantics: ‘We cannot police half the world at our own expense when we have already gone in pawn to the other half.’122 Predominant among that other half was the United States. Its financial leverage over Britain would be exerted to devastating effect in the Suez crisis of 1956. Yet, in the decades either side of that pivotal imperial collapse, the US imposed remarkably little pressure on the British, preferring the strategic certainties of colonial anti-Communism to the political uncertainties of a post-colonial world.123

Nowhere was Washington’s more benevolent view of European imperial restoration more apparent than in Southeast Asia. British strategic planners, who had been finalizing plans laid in September 1944 to ‘liberate’ Singapore and Malaya, were overtaken by Japan’s surrender after the atomic bombings of August 1945. With US approval, a decorous British amphibious assault went ahead in Malaya on 12 September, its purpose symbolic rather than military. An intelligence officer remembered their bizarre quality: ‘A full-dress landing was made through the surf’, and he spoke feelingly of the experience ‘of wading ashore with rifle in hand before an admiring audience of Malays dressed in their holiday best and applauding eagerly.’124 One reason for this demonstration of British military prowess was to conceal the fact that the Communist guerrillas of the Malayan Peoples Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) had actually fought the Japanese during the war’s closing stages. Whether in British Malaya, French Indochina, or Dutch Indonesia, the spectre of Communists seizing control before colonial administration could be restored was too much for President Truman’s new administration to swallow. Superficially at least, Malaya posed fewest problems. Speedy establishment of a transitional British Military Administration enabled Admiral Mountbatten’s South East Asia Command to marginalize the MPAJA. Disbarred from mainstream colonial politics, the Malayan Communist Party instead consolidated its grip over two discrete constituencies: Malaya’s industrial trade unions and its rural Chinese workforce; their appeals to both enhanced by severe post-war rice shortages.125 This was to have devastating consequences. In the short-term, though, Indochina’s social breakdown loomed larger. In southern Vietnam British imperial forces took over as transitional occupiers pending the arrival of a French ‘expeditionary force’ in Saigon in September 1945. But the Vietminh was not about to be cast aside.

With an empire wracked by internal division and violence, the ebullience of French imperialism in 1945 seems puzzling.126 Whereas, over the ensuing decades, Britain would adjust, albeit painfully, to America’s new global dominance, successive French governments reacted in contrary fashion, equating retention of empire with resurgent international power. It was, after all, the colonies that made Free France credible, not just as a political force but as a territorial entity. Even though, in terms of volume and value, French colonial trade improved sharply over the course of 1944, in purely monetary terms France’s empire was not generating foreign exchange revenues comparable to the sums derived from British territories.127 So it was perhaps unsurprising that de Gaulle’s senior advisers viewed imperial affairs in instrumental terms. In the months preceding the D-Day landings, this boiled down to a simple calculation: colonial reforms should enhance French power, not diminish it.128

In January 1944 the Governors of the Free French Empire assembled in Brazzaville, the sleepy Congolese capital of French Equatorial Africa, to consider the empire’s post-war consolidation. The tenor of their discussions was deeply conservative. North Africa and Indochina—the regions where wartime disruption was greatest—were scratched from the conference agenda.129 And plans for administrative restructuring, economic diversification, and greater electoral representation in territories south of the Sahara were profoundly cautious. They were framed, not in terms of preparation for independence, but the acquisition of a more francophone personnalité politique in individual colonies.130 Put differently, wider citizenship rights, political responsibilities, and improved living standards, however enacted once the war was over, were intended to make colonial peoples more French, not less.

The ‘colonial myth’ that keeping empire intact was somehow pivotal to French grandeur was not confined to the Gaullist right, despite its self-proclaimed role as arch defender of France’s historical greatness. The imperialist reflex was prevalent throughout the political community in liberated France. Even the Communist leadership, rhetorically anti-colonial to be sure, was not immune. Why? The unique circumstances of France’s wartime defeat, liberation, and reconstruction offer some explanation. France’s acute weakness compared with its major allies in 1945 nurtured the presumption that empire was fundamental to French recovery.131 This view spanned the restyled French party-political spectrum. It was readily accepted by former resisters, erstwhile Vichyites and, it appears, newly-enfranchised women voters. The acrimonious circumstances of France’s eventual pull-out from Syria and Lebanon in 1944–6 helped turn presumption into dogma by the time the Indochina War broke out in December 1946.

Having negotiated (but not implemented) treaties of independence with the two Levant states in 1936, French governments exploited communal unrest and the outbreak of war in Europe to postpone consideration of a transfer of power. This pattern of obfuscation, justified by reference to internal disorder and France’s primordial strategic requirements, continued during the war years, unaffected by the sequence of Vichy and Free French rule. France’s imperial authority drained away regardless. In November 1943 Lebanese and Syrian parliamentarians took decisive steps towards unilateral declarations of independence that made French rule untenable. In Beirut and Damascus populations enthused by long-delayed fulfilment of their claims to sovereignty understandably refused to knuckle under when the French authorities tried to re-impose their mastery. Local opposition to it proved unrelenting. And British determination to rebuild its Arab connections precluded support for a hated French administration.132 The stern resistance of Syria’s pro-Vichy garrison to a British-led imperial invasion force in June–July 1941 nourished British contempt for French sensibilities. So incensed were the Vichy authorities of the time that they lobbied Hitler’s government to authorize Luftwaffe raids against British Palestine’s oil installations and urban centres.133

Beneficiaries of Syria’s regime change over the summer of 1941, the Free French were no less suspicious of ulterior British motives. By 1944 the French Levant was critical of emerging British plans to redraw the boundaries of a ‘Greater Syria’ as part of a definitive Palestine partition.134 De Gaulle raged against this scheming. It was, he said, tantamount to covert imperial warfare against an ally.135 From its inception in July 1944 de Gaulle’s provisional government railed against what were regarded as British diktats imposing withdrawal. Far from admitting the inevitability of a pull-out, throughout 1945 the Paris authorities interpreted British pressure for evacuation as a conspiracy to buy Arab friendship at French expense.136 Meanwhile, in the fast-developing secret intelligence war between the two imperial powers, French security services began supplying arms and information to the Zionist terrorist groups Irgun Tzva’i Le’umi (National Military Organization) and the Stern Gang.137

Syria provoked the severest breakdown in Anglo-French imperial relations of the decolonization era. Last-ditch French efforts to stave off Syrian and Lebanese independence were matched by countervailing British pressure to accelerate the process (an ironic counter-point to subsequent British anger over US actions over Palestine). Faced with uncompromising nationalist opposition and Britain’s decisive military presence, French evacuation was unavoidable. That it occurred only after bloodshed and amidst bitter acrimony between France and the nationalist governments in Damascus and Beirut was not. The venomous divisions between French and British authorities in the Middle East were partly to blame. So, too, was the reconstructed imperialism of the early Fourth Republic, which fed the mistaken presumption that France might yet salvage its position. This hard-line stance was doubly ironic in Syria, where the French had twice abandoned territory at the Mandate’s northern margins in order to placate Kemalist Turkey—first in Cilicia in 1921 and, second, in the sanjak of Alexandretta in 1938. Such pragmatism—and readiness to choose flight over fight—was forgotten amidst the fury of France’s final withdrawal.138

For all sides involved, the material aspects to the Levant dispute—control over local security forces, provision for base rights, and the recognition of French educational privileges—held particular symbolic value. To the Syrian and Lebanese authorities the right to raise sovereign security forces was the yardstick of true independence.139 For French negotiators, continued control over a handful of schools and military bases retained a cultural significance disproportionate to their material value. Meanwhile, for the British government, and Ernest Bevin’s Foreign Office above all, the Levant settlement was subsumed within the central preoccupation of their Middle East policy—to conserve Britain’s regional influence after the end of the Palestine Mandate.140

Neither France nor Britain emerged with much credit from this contest. The unpopularity of the local French administration, the délégation générale, made a mockery of the high price placed by French negotiators on their cultural legacy in the Levant states, something that American, Arab League, and United Nations observers found incomprehensible. But it was the violence that attended the Syrian endgame that utterly discredited French imperialism in the Middle East. Over two days on 29–30 May 1945 French artillery pounded the Damascus Parliament building and its environs. The bombardment marked the culmination of three weeks of smaller-scale clashes in the capital as French army reinforcements battled with Syrian security forces for control of the streets. The French commander General Fernand Oliva-Roget lost patience with this skirmishing and let loose his forces to teach the Syrians ‘a good lesson’.141 Hundreds died. North and West African colonial troops were quickly put to work burying Syrian gendarmes and other protestors in mass graves, making it impossible to calculate the numbers killed.142 This bloody show of imperial defiance tipped the balance. Britain’s Middle East Army Command, technically the ultimate military authority in the region, assumed full control in Syria, imposing martial law and confining the French garrison to its barracks. Negotiations over the terms of the French pull-out resumed, but their Mandate was already dead.143

The French coalition government, smarting from this humiliation, became doubly resolved to hang on elsewhere. As we shall see, the Syrian experience compounded French intransigence in talks with Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnamese Republic in early 1946. Covert French support for Zionist terrorism in Palestine was stepped up, as much a means of exacting revenge against British betrayal as a shrewd strategic gamble on the future power of Israel.144 The British, preoccupied by the problems of Palestine partition, a Hashemite Greater Syria, and the renegotiation of Anglo-Arab treaties, had exploited the opportunity to capitalize upon French weakness to curry Arab favour. Viewed from this perspective, withdrawal from the Levant revealed as much about the complexities of Britain’s effort to safeguard its Middle Eastern power as it did about France’s reluctance to decolonize.145

Britain’s efforts to spread limited military resources widely enough to safeguard its empire against all potential threats were doomed once Japan resolved on its own bid for imperial supremacy in eastern Asia. What John Darwin has called Britain’s ‘strategy of shuffle’ was quickly revealed for what it was: a sleight of hand with only half the cards necessary for success.146 Although phrasing things rather differently, Keith Jeffery, another shrewd analyst of Britain’s wartime imperial problems, reaches a similar conclusion: ‘Paradoxically, the ultimate cost of defending the British Empire during the Second World War was the Empire itself.’147 Both writers agree that this, the biggest fight undertaken by Britain in defence of its empire, undermined the entire construct. The door was thereby opened to new strategies of accommodation with those demanding colonial change after the war. Britain’s post-war turn towards flight, soon to reach fulfilment in South Asia, was rendered possible, imperative even, by the preceding commitment to keep the empire intact under the stresses of World War. This connection between victory and empire dissolution was, at once, paradoxical and remarkably simple. The imperial cost of Britain’s triumph of arms was decolonization.

What about France? The country moved, in rapid succession from a nation defeated and occupied to one liberated and resurgent. A longer wartime constant was the state of undeclared civil war in its colonies. From June 1940 until Japan’s final overthrow of the Vichyite regime in Hanoi on 9 March 1945, the French empire was torn apart by an internecine war between the civil–military elites who ran it. Its endless factionalism antagonized the local elites essential to empire governance, presenting a golden opportunity for radical anti-colonial groups like Algeria’s PPA and the Vietminh resistance. The result was a crisis of colonial legitimacy that the French Empire never quite shook off. The Vichy–Free French antagonism was also sharpened by the weaknesses of each protagonist. Leaders on both sides of this Franco-French divide were acutely conscious of their relative powerlessness next to stronger European, American, or Asian clients. It was these outsiders—British, American, German, or Japanese, who, time and again, demonstrated that they controlled the wartime disposition of French colonial territory.

Nazi Germany, perhaps unrealistically, treated French North Africa as a strategic pawn until America took over following the Torch landings of November 1942. And where Gaullist administrations refused to bend to American wishes, as in Pacific New Caledonia or the tiny islands of St Pierre and Miquelon off the Newfoundland coast, the political consequences of deeper US antagonism were greater than the amour-propre satisfied by petty displays of French independence. Britain, meanwhile, pulled the key imperial levers in Syria and Lebanon after July 1941. British and Dominion forces also precipitated changes of administration, although not of underlying colonial conditions, in French Somaliland and Madagascar in 1942. Ultimately, though, it was Japan that did most to knock over France’s house of colonial cards. Its occupation of Indochina, partial at first, total and brutal at last, catalysed the first of France’s major fights against decolonization—an eight-year war against the Vietminh that reverberated throughout Southeast Asia and the colonial world.148