In October 1938 the French steamer Ville de Reims loaded an unusual cargo on the Algiers dockside. It was a casket containing the mortal remains of Queen Ranavalona III, the last monarch of Madagascar’s Merina dynasty.1 Ranavalona spent twenty years in Algerian exile before her death on 23 May 1917. She was evicted from her homeland by Madagascar’s first colonial pro-consul General Joseph Gallieni, a rarity among France’s senior soldiers in his fervent republicanism. Of relatively modest background himself, Gallieni was hostile to monarchical privilege in principle and hostile to Ranavalona’s dynasty in particular. He reserved his deepest loathing for certain members of the Merina elite who refused to submit to a French colonial conquest, which on 30 September 1895 culminated in the occupation of the capital Tananarive (now Antananarivo), centre of the pre-colonial monarchy of Imerina. Concentrated around the highland plateaux of central Madagascar, the Merina had long been the Island’s dominant ethnic group. Many, including the Queen’s family, were Protestants, converted by British missionaries in the nineteenth century.2 Indeed, popular hostility to Merina notables, and the missionary state-church they supported was integral to the Menalamba or Red Shawls revolt of 1896–7.3 The uprising was substantially traceable to local causes. Among these, worsening famine conditions, forced labour requisitions, and a domineering ecclesiastical system left in place by the conquest figured largest. But the Menalamba revolt was also a last-ditch resistance to creeping French imperial control, and it was for this that it was popularly remembered—and celebrated. The revolt of the Red Shawls remained a cultural reference point for Malagasy nationalists for decades.4

Gallieni’s plans to implant French imperial administration required the displacement of Merina influence and the subjugation of the inhabitants of Madagascar’s rural interior. Subsequent colonial administrations, first military, then civilian, although avowedly committed to a policy of cooperative ‘association’, followed the General’s lead in exploiting the economic divisions between Malagasy social groups and the acute provincial suspicion of the old Merina elite.5 For those Malagasy, including former East African slaves once subordinated to the Merina, collectively assigned the colonial appellation côtiers, or coastal peoples, the French takeover was not quite the disaster that it was for the old royal elite.6 For one thing, the French colonizers formally abolished Malagasy slavery in 1896. For another, the entire colonial project rested on the construction of a new export economy at variance with the slave-based economic system of Imerina.7

Not surprisingly, in subsequent years and decades, Merina notables figured within secret societies and, later, political parties, whose central objectives were to cast off the colonial yoke and restore Merina primacy.8 As time wore on, other more modern ideas, socialism and nationalism prominent among them, exerted a stronger grip over Malagasy politics. Long before the people of Madagascar rebelled against French rule, the issues of independence and the role of the state had become entangled with historic ethnic divisions between Malagasy communities of Malay and Bantu origin. Thus, by the time that Ranavalona was shipped home in 1938, it was hard to distinguish the older accents of Merina communal loyalty from the newer inflexions of Malagasy popular nationalism.

Why, then, was the Ville de Reims steaming southward with the Queen’s remains in late 1938? The answer, at one level, is that the colonial administration, still affected by the Popular Front’s reforming humanism, wished to give tangible expression to its message of inter-ethnic reconciliation under benevolent French control. The pomp of a state-conferred funeral for a once-revered monarch conveyed a simple message: the violence and injustice of conquest were things of the past. Certainly, the returning Queen was treated with greater dignity in death than in life. She was re-interred alongside her royal forebears in an elaborate ceremony presided over by the French head of Madagascar’s Protestant mission.9 At another, deeper level Ranavalona’s burial was sheer expediency. It helped disarm persistent Merina criticism of cultural insensitivity. And it offered a memorable public display to obscure the crackdown against Malagasy political parties then under way.

Madagascar’s promised reconciliation with its colonial overseers was not to be. The coming of war in 1939 accentuated the divisions in island politics, both French and Malagasy. At the centre of colonial power, the sequence of Vichy administration followed by a British-backed Gaullist takeover in 1942–3 brought with it the familiar strains of increasingly authoritarian rule and extractive economics as Madagascar was coerced into serving a distant war effort.10 For the wider population, mounting forced labour exactions provoked especially deep resentments that would resurface after the war.11

For a brief post-war moment during 1945 and 1946 the political skies brightened, even so. Renowned for consolidating a labour inspection service in French West Africa, a new colonial governor, Marcel de Coppet, promised a clean break with the wartime past.12 Government was overhauled and new provincial assemblies elected over the autumn of 1946.13 In practice, these measures backfired, opening up enough political space to reveal the depth of Malagasy antagonism to French domination. In short, the underlying tensions revealed by Ranavalona’s return were still evident when Madagascar exploded into rebellion ten years later. Administrative practices and the disbursement of money and favour still exploited Malagasy ethnic divides. Suspicion of surreptitious Merina disloyalty endured, especially within the colony’s security services. And the government’s ‘native affairs service’ refused to accept the advent of political modernity signified by a vibrant, left-leaning Malagasy nationalism.14 Most important of all, rural antagonism to externally-imposed systems of cultural belief, land use, and labour recruitment was, if anything, stronger than ever. The grievances of the Red Shawls resonated still.15

Rebellion broke out on the island of Madagascar on the night of 29 March 1947. Coordinated attacks were launched against widely-separated targets, including a military base at Moramanga in the centre of the island. Here and elsewhere the rebels were unsuccessful in their key objective: to secure modern weapons.16 Planned urban uprisings in Tananarive and Fianarantsoa fell through, largely because additional troops and police were deployed, although the colonial infantry garrison in the northern port of Diego-Suarez did go over to the rebels.17 After these initial reverses, the uprising never engulfed the entire island. But, in large swathes of eastern farmland and forest, disorder was sufficiently widespread to prompt a large-scale military intervention led by Foreign Legion and other specialist empire infantry trained for the dirty business of imperial policing. During April and May 1947, before these reinforcements arrived, the insurrection escalated steadily. The insurgents took advantage of dry-season conditions to move relatively freely through the countryside. For the authorities, the island’s rail system was judged particularly unsafe. Locomotives sat in station sidings daubed with nationalist graffiti; bridges and sections of track were destroyed. In the first days after the outbreak the Governor was even compelled to requisition two Air France civil aircraft to allow him to visit victims of rebel attacks.18

The rebels meanwhile edged closer towards the capital, Tananarive, in Madagascar’s central highlands. Road and rail links were cut, although the city itself never suffered sustained attack.19 The strategic balance shifted once the colonial troops, spearheaded by two further battalions of West African tirailleurs sénégalais, disembarked in May and June.20 Some estimates point to a French suppression so severe that, by the time the island’s rebellion was declared over in 1949, over 100,000 Malagasy people among a population less than four million-strong had been killed. Certainly, the revolt marked the worst violence in a French African territory since the Rif War in Morocco twenty years earlier. Among those who lost their lives, the elimination of an entire political class of Malagasy opposition illustrates both the devastating legacy of a colonial power’s decision to fight rather than negotiate and the narrowing of political choices it produced.

Leading Malagasy politicians were among over 600 arrested for sedition within the first days of the disorders.21 Among them were Joseph Raseta, Joseph Ravoahangy, and Jacques Rabemananjara, the island’s three deputies, the elected parliamentary representatives to the National Assembly in Paris. Ravoahangy and Rabemananjara were taken into custody by the island’s police chief Marcel Baron on 12 April 1947. Raseta, already a marked man, remained free a little longer as he was in Paris at the time.22 On 6 May he took to the floor of the National Assembly to refute the allegations against him. Few remembered his speech because of the spectacle of what followed. Jules Castellani, one of Madagascar’s settler deputies, outraged by Raseta’s temerity, slapped him in the face.23 Why such fury? Raseta and Rovoahangy were founding members of the Mouvement Démocratique de la Rénovation Malgache (MDRM), the nationalist party established in February 1946 that was accused of directing the uprising.24 Rabemananjara put his elite Merina lineage and outstanding literary skills to good use as MDRM secretary-general and chief orator for Malagasy nationalism.25 They would soon achieve greater international notoriety as the Fourth Union’s pre-eminent political prisoners. Two French-trained medical doctors and a noted writer, the trio made unlikely revolutionaries.26 So much so that the details of the MDRM’s rapid rise and the trial of its leaders are worth dwelling on because of the unscrupulous colonial officialdom they reveal.

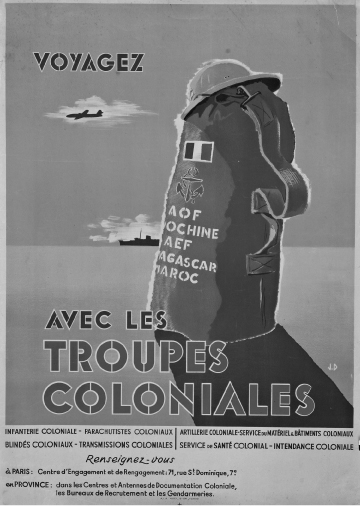

Figure 11. Post-war French recruitment for the Troupes Coloniales. Madagascar is included, alongside Indochina, Morocco, and the black African federations, as likely destinations for service.

The MDRM’s cellular structure and executive ‘bureau’ mimicked the working practices of the Madagascan Communist Party, which had itself emerged in the freer political atmosphere created by Popular Front reforms in 1936–7. MDRM leaders, including Ravoahangy and Raseta, honed their organizational skills as Communist activists, a path that earned them the enduring hatred of Madagascar’s colonial police.27 Sûreté suspicions deepened when both men rubbed shoulders with their old colonial comrade Ho Chi Minh during the Vietnamese leader’s stay in Paris during 1946.28 By January 1947 MDRM organizers were being tailed, informants monitored party meetings, and government clerks thought to sympathize with the movement were brought in for questioning.29 For all that, the MDRM was becoming a broader ideological church. It enjoyed the support of both the Parti nationaliste malgache (PA.NA.MA.), a group particularly strong in the south of the Island, as well as the ‘JINA’, pre-eminent among the secret societies that were a constant fixture of Madagascar’s colonial politics. With a membership estimated at 300,000, on 21 March 1946 the MDRM leadership demanded French recognition of Madagascar as a free state within the French Union with its own government, legislature, and armed forces.30 But not all the Malagasy were enthused by the prospect of MDRM control.

The socio-ethnic divisions between the peoples of the western and north-western coastal provinces and the Merina of the high plateaux around Tananarive, closely identified with the pre-colonial monarchy, still resonated. In several provinces, victory for the MDRM was widely seen as the precursor to Merina domination. Bitterness towards Merina elitism was perhaps sharpest amongst the Hova Mainty, formerly a slave caste under the Merina dynasty in the nineteenth century. These two anti-Merina constituencies, one regional, the other caste-based, united in the Parti des déshérités de Madagascar (Party of the Disinherited of Madagascar—PADESM), a political party whose nomenclature revealed its animus against the MDRM and Merina hegemony more broadly.31 Within weeks of its foundation in June 1946, the PADESM was co-opted by Governor de Coppet’s administration to thwart the MDRM’s advance. Plans were agreed, but, as yet, unimplemented, with the Ministry of Overseas France to outlaw the Movement. And at local level, the settler community willingly bankrolled PADESM candidates in provincial elections in January 1947.32

Back in Paris, meanwhile, colonial problems had driven a wedge into Paul Ramadier’s government, the last of the post-war centre-leftist coalitions in office between 1944 and 1947. It is worth revisiting these before we return to Madagascar. To begin with, modernization schemes to partner the launch of the French Union were still to be finalized. Like its domestic equivalent, Jean Monnet’s grand plan for French industrial renovation, colonial development divided dirigiste planners from economic liberals.33 Whichever proposals were approved seemed likely to hit the rocks of France’s chronic dollar shortage.34 Algeria raised other problems. The coalition partners and their local party sections within Algeria concurred that independence was out of the question, but agreed on little else.35 These differences crystallized around Algeria’s post-war ‘Statute’, meant to define the status of France’s premier overseas possession in relation to the new Fourth Republic and the French Union. With minimal underlying agreement, the necessary legislation was slow in coming. The governing parties divided over Algerian voting rights and the extent of the territory’s assimilation to France.36 And recriminations continued about the disastrous Sétif uprising in Eastern Algeria, whose suppression over the summer of 1945 had cost at least 7,000 Algerian lives, probably more.37

The most immediate colonial problem, though, remained Indochina. Ramadier’s Socialists were becoming uncomfortable at their identification with an expanding war in Vietnam, whose prosecution their Christian Democrat coalition partners the MRP increasingly controlled.38 The dynamics of coalition-making and the recurrence of votes—over the new constitution, as well as national, provincial, and municipal elections—in a country rebuilding itself after war and occupation was especially damaging in this regard. A sideways glance at the MRP explains this point. Hitherto the strongest of the Fourth Republic’s new political parties, the MRP’s grass-roots support had three distinct traits: it was provincial, female, and Catholic. Christian Democracy put down its deepest roots in Brittany and the strongly Catholic eastern provinces of Alsace and Lorraine.39 Unfortunately for the Party’s electoral planners, this profile of support corresponded closely with that of the Gaullist movement, the RPF. True to their leader, the Gaullists remained unremittingly hostile to a constitutional settlement that precluded strong presidential politics in favour of multi-party consensus.40 If things went badly for the incumbent government, disenchanted MRP voters were liable to be seduced by the RPF’s blend of social conservatism and uncompromising patriotism. De Gaulle’s supporters at this stage had little truck with anything that smacked of imperial retreat.41 Looking warily over their right shoulder at the strengthening Gaullist challenge, MRP ministers like Robert Schuman, Georges Bidault, and Paul Coste-Floret gravitated naturally towards a colonial hard-line.42

The other major partner in the tripartite coalition, the Communist Party, was, by contrast, fast approaching outright opposition to the fight against the Vietminh.43 This was problematic not least because a Communist Defence Minister, the Marseille deputy François Billoux, technically oversaw the military strategy pursued. In a March 1947 National Assembly debate that descended into a brawl, Billoux, an International Brigade volunteer of the Spanish Civil War, pointedly withheld his support for expeditionary force intervention in Vietnam.44 The French left’s longstanding inter-party rivalries, never dormant in spite of the coalition partnership between Socialists and Communists, intervened here. The PCF registered major gains in the November 1946 general election, during which the Socialist vote, in particular, fell back. To complicate matters further, the UDSR, centre-left cousins of the Socialists, had fought the November election in partnership with the Radical Party as a combined block, the Rassemblement des Gauches Républicaines (RGR, the Left-Republican Group). Neither much of a group nor especially left-wing, the one thing RGR members agreed on was their opposition to the Communists.45 Outflanked by the Communists on one side and by the RGR on the other, it became harder still for Ramadier’s Socialist Party colleagues to swallow their objections while PCF ministers and the Communist daily L’Humanité vilified official policy.46 Coalition government, they insisted, required responsible—and collective—decision-making, not electoral grand-standing and a narrowly ideological approach to difficult policy options.47

With a long hot summer of French labour unrest looming, the Communists, their Stalinist credentials no longer hidden up their sleeve, looked increasingly out of place inside a Cabinet that aligned itself against workers’ demands at home, with imperial interests in the empire, and alongside Washington in the emerging Cold War. 1947, in other words, was a year of fateful choices for those in power in France.48 Within a matter of months these testing policy choices caused centre-left tripartism to unravel only for a new coalition combination to take shape around the MRP and the Radical Party—the so-called Third Force. By the end of the year France had moved firmly rightwards.

Framed within this shifting political, imperial, and strategic landscape, Madagascar represented an unwelcome problem at an unpropitious time. Ramadier’s senior ministers wanted it quickly contained. This helps explain why the government acceded to an 11 April request from Marcel de Coppet to revoke the three Malagasy deputies’ parliamentary privileges.49 The Governor insisted that the MDRM executive was solidly united behind the uprising. Police seizures of party documents, as well as interrogation of the first detainees, revealed that the key decisions were taken on the night of 17 March. It was then that plans were finalized for coordinated attacks in the capital and regional party cells were given instructions on targets to attack.50 Armed with such damning evidence, National Assembly members, who did not even debate the rebellion until a full month after its outbreak, wasted little time questioning their fellow parliamentarians’ guilt. The MDRM trio’s immunity from prosecution was lifted by a vote of 324 to 195 on 6 June.51 Raseta was taken into custody as he left the Assembly building. With all three MDRM deputies now behind bars and gruesome revelations of the murders of settlers hitting the headlines, the trio were condemned as ‘murderers’ in the French press before their cases went to trial, a blatant violation of basic judicial standards that outraged the writer Albert Camus.52 But this was as nothing compared to events in Tananarive.

The charges of ‘conspiracy against the state and endangering national security’ levelled against the three parliamentarians rested on three main sources of evidence.53 First was an MDRM Political Bureau telegram sent on 27 March 1947, two days before the rebellion began. With an eye to impending elections, the leadership advised local party sections to avoid involvement in political violence. Although Raseta and Ravoahangy were elected in November 1946 on a pro-independence ticket, the MDRM’s senior leaders recognized that nationalist militancy simply invited a ban on the Party’s activities.54 So their instructions reminded their local supporters that the movement stood for Malagasy autonomy within the French Union. In an extraordinary act of evidential reinterpretation, prosecutors read the telegram’s contents as a coded message to MDRM organizers to unleash the revolt.55 The second source of ‘evidence’ against the deputies was a series of confessions extracted from several local MDRM activists. Some confessed under police torture; others did so in response to death threats. Insistent that these admissions were reliable nonetheless, Sûreté chief Baron advised prosecutors that they confirmed the coded telegram accusation. The third piece of evidence was the testimony expected from the defence team’s star witness Samuel Rakotondrabé, a Tananarive tobacco factory manager who was also a leading activist in the JINA. The problem for the authorities here was less the reliability of what Rakotondrabé might say, but the prospect of him saying anything at all. The deputies’ defence team were relying on Rakotondrabé’s testimony to confirm from a participant’s perspective that the rebellion was locally organized. The case built up by the police and the colonial authorities would explode. Not surprisingly, the prosecution preferred the account of Rakotondrabé’s associate Edmond Ravelonahina. He suggested that the parliamentarians masterminded the original uprising in the critical nights preceding 29 March. It was only after the deputies’ trial that Ravelonahina’s evidence was proved inconsistent and false; in short, a police concoction.56

A great deal was hanging on Rakotondrabé’s willingness to contradict the emerging official story. Unlike Ravelonahina, whose trial before a military court was still pending, Rakotondrabé had nothing to lose by telling the truth. He was among seventeen former rebels already sentenced to death for involvement in the rebellion’s first killings. But his march to the guillotine awaited the outcome of clemency appeals to the Minister for Overseas France. The minister in question, the socialist veteran Marius Moutet, might have been expected to look kindly on the condemned men. He had ordered the release of thousands of Vietnamese and Malagasy political prisoners in 1936–7 as part of the Popular Front’s brief experiment with colonial reform. A decade later, in the midst of the Indochina War and with memories of a horrendous 1945 uprising in eastern Algeria seared into French memory, Moutet reacted very differently. With the Malagasy politicians’ trial looming, on 5 July Madagascar’s colonial government formally asked the Minister to make his mind up, warning that further delay in carrying out the executions diminished their power of ‘intimidation’. To the delight of the colonial authorities, the police, and the prosecutors in Madagascar’s capital, Tananarive, Rakotondrabé was executed on 18 July 1948.57 This was three days before the trial of the deputies and twenty-nine other alleged rebel organizers opened in Tananarive’s criminal court.58

Madagascar’s Bar Association prohibited any of its members from acting as defence counsel for the MDRM detainees. It was a Paris lawyer, Pierre Stibbe, who agreed to take on the case. He faced relentless harassment after his arrival on the island and narrowly escaped a grenade thrown from a police car. Stibbe’s associate Henri Douzon was even less fortunate. He was kidnapped, almost certainly with police connivance, and badly beaten. The abuse of the trial lawyers and the obvious flaws in the evidence, which the judge admitted but discounted, portended the inevitable outcome. Few were surprised when, in one of the French Empire’s most infamous show trials, Raseta and Ravoahangy were handed down death sentences on 4 October 1948.59 Rabemananjara got forced labour for life. The manner of their conviction illustrated the dismissive intolerance of Malagasy dissent that characterized French actions throughout the rebellion years.

Ultimately, the deputies escaped the guillotine, but not lengthy prison terms. On 15 July 1949 President Vincent Auriol commuted their death sentences to life terms in a high-security prison, the prelude to their transfer to a Corsican jail in September 1950.60 The three deputies’ imprisonment made them an early focal point for French intellectual and confessional opposition to colonialism just as the conviction of Captain Alfred Dreyfus had galvanized opinion against racial injustice half a century earlier. In the first months of the rebellion, the League for the Rights of Man, the leading human rights group in France established in response to the Dreyfus case, joined student groups, French and colonial lawyers’ associations, church leaders, and anti-colonial activists in condemning the abuse of Malagasy political prisoners.61 Its volume steadily increasing, this clamour of opposition was slow to register with France’s rulers. Despite the glaring flaws in the case against them, like Dreyfus, it was years before the three politicians were finally amnestied—in March 1956.62 Their fate became emblematic of a fight strategy that, by crushing dissent, halted Madagascar’s path to decolonization for over a decade.

At its most severe along Madagascar’s eastern coastal belt, particularly in what is now Toamasina province, where estate farming and labour requisitioning went furthest, the Malagasy uprising destabilized Madagascar’s principal export industries. Eastern settlements from Moramanga, southward to the port of Tamatave (Toamasina) and on towards Mahanoro and Manajary all saw local commerce collapse within weeks of the start of the fighting in late March 1947.63 The island’s coffee growers were especially hard-hit. Some settler-owned plantations were targeted, their properties and crops burned. Others were looted, their stores of dried coffee sold on to fund rebel arms purchases. Even those who escaped such violence complained that continuing insecurity prevented them from recruiting estate labour and continuing to cultivate. Most planters in the eastern regions badly affected by the rebellion were unable either to harvest their coffee crop or to distribute it for sale. And with so much stolen coffee flooding Madagascar’s domestic market, prices collapsed. Much the same occurred within rice-growing areas around Fianarantsoa further to the south, where crop production ground to a halt during late 1947. This was what peasant rebellion meant for those caught up in it.

Episodic violence on estates and smallholdings stifled agricultural production, choked off sources of labour, and, in remarkably quick time, brought small- and large-scale cultivators face to face with economic ruin. Seen from a colonial perspective, the underlying issue was security. Without an assured military and police presence, the rhythm of local economic activity could not quicken. Reviewing the rebellion’s opening months between April and August 1947, the Ministry of Overseas France conceded that locally available troops and police had no hope of guaranteeing such security across broad stretches of northern and eastern Madagascar.64

Pending the arrival of army reinforcements, mainly professional colonial army units en route to the war in Indochina, security operations were largely confined to the protection of urban centres, railways, and other strategic nodal points. Thereafter, the colonial authorities applied a simple measurement for the restoration of security: could Europeans travel safely without a military escort? Judged by that criterion, the colonial government acknowledged that they controlled less than five per cent of the terrain and only two per cent of the population in heavily-settled areas along Madagascar’s east coast. Numerous rural settlements and isolated estates were totally cut off. Food was parachuted in because travel by road was deemed too dangerous. In all, some 150 Europeans lost their lives during the rebellion, a figure far in excess of the numbers of colons murdered in Algeria’s Sétif uprising two years earlier.65 Admittedly, the numbers of planters and local villagers killed by rebels were relatively small when compared with levels of violence in Indochina and, later, Algeria. But the manner of their deaths—hacked with farm implements, sometimes tortured—and the sense of exposure to sudden attack without hope of rescue was profoundly unsettling.66

This pattern of isolated European farmers exposed to outpourings of collective violence would recur in a British colonial context with the coming of Mau Mau to Kenya. But it was French Madagascar that experienced it first. And, as in the Kenyan case discussed below, it was this utter collapse in colonial order that led to the massive security force violence that followed.67 The outcome was never in much doubt. Although they adopted an army’s nomenclature and ranks, the insurgents lacked the advantages of military communications or transport. Coordination, even basic connection, became harder to sustain as French forces imposed security perimeters around areas of rebel activity.68

Aside from suppressing the Mandritsara uprising, a separate rebellion in the island’s far north, the army set about ‘caging’ the entire rebel-controlled zone to the east. This amounted to over 100,000 square kilometres of territory of which about forty per cent was heavily forested.69 Forest fighting was slow and dangerous. Targeting the rebels’ supporters and, it was presumed, their suppliers in farming settlements was quicker and easier. Punitive columns swept through villages dispensing instant retribution because, in security force parlance, the entire area was hostile ground. Villages were burned to a cinder, sometimes with the occupants trapped inside their homes. Levels of destruction were such that entire rural communities were erased from the map. The impact of state coercion was as much ethnic as party political. French repression had particularly devastating effects on the Betsimisaraka people in eastern Madagascar. Their villages gone, their livestock slaughtered, unable even to conduct customary burial and mourning rites, families hiding in the forests were now denied access to food. Yet, even as starvation took hold, few rebel fighters surrendered. Some had taken oaths to protect their ancestral land to the death.70 And many were surely aware that summary execution or lengthy punishments of forced labour awaited them.71

By April 1948 the official list of political prisoners reached 5,750.72 Making prisoners perform hard labour was also highly symbolic. Before the revolt erupted, Madagascar’s settler farmers expressed outrage at the impending abolition of forced labour throughout the empire. This long overdue reform was finally secured in March 1946, twelve months before Madagascar’s insurrection. Its passage into law followed intensive lobbying by several African deputies including the Malian Fily Dabo Sissoko, the Senegalese Lamine Guèye and Léopold Senghor, and, above all, Ivory Coast’s Félix Houphouët-Boigny.73 The success of their efforts in Paris suggested to Madagascar’s estate-owners that the colonial world was being turned upside down. They complained of estate operations rendered unviable overnight. For its part, MDRM propaganda identified the harsh exploitation of Madagascar’s agricultural labourers as the clearest evidence of colonial iniquity.74 Yet still the official rhetoric insisted that military saturation and severe punishment were the essential preludes to the restoration of normality, the resumption of traditional patron–client relationships in the countryside, and eventual inter-communal reconciliation.

The Governor, de Coppet, and his successor Pierre de Chevigné, reclassified as a High Commissioner as part of the French Union’s elision of direct colonial references, were firm supporters of the clampdown. In October 1947 the administration imposed stringent limits on party political activity, backed by strict press censorship. Suspected MDRM sympathizers were purged from administrative posts. De Chevigné took charge of the repression from February 1948, insisting that most of the Malagasy had remained ‘non-political’ and, through it all, loyal. Government statements conflated the MDRM with Merina exclusivity and rebel violence, not an authentic popular nationalism.75

Even Marius Moutet at the Ministry for Overseas France maintained that it was the MDRM who were guilty of racial killings, not the French.76 Their rationale for these statements drew on a familiar strand of imperialist thought, popular among liberal republicans. Its self-serving logic was transparently obvious: a subject population, unschooled in the ways of politics, had been misled by extremist outsiders, in this case, supporters of a Messianic and racist nationalist group. The silent majority, whose horizons were bounded by the village, the crop cycle and their customary beliefs, responded best to unequivocal lessons and exemplary discipline.77 Even the small minority of rebel troublemakers probably had little idea of what they really wanted and were themselves victims of the even smaller nationalist intellectual elite. Most within this latter category were members of the Merina ethnic group that once ruled independent Madagascar. Many were educated town-dwellers or landowners with little appreciation for the lives of the rural poor. Thus, to the ethnic stereotyping that underpinned colonial disciplinary violence a layer of class war was added. The Merina, usurped by a benevolent and modernizing French colonial regime, were accused of cynical manipulation. They hid their efforts to reclaim lost pre-eminence by dressing in the garb of anti-colonial nationalism.78

In line with this thinking, MDRM activists faced the harshest punishments of all. By late December 1947 the area under rebel control had contracted by over two-thirds. At least 200,000 Malagasy nationalists submitted to government authority, and the MDRM was utterly broken, with some 2,500 of its members imprisoned on sedition charges. Some were summarily executed, others tortured first.79 Still more were beaten unconscious and dropped from aircraft into the Indian Ocean. In one notorious case in May 1947, 165 rebel suspects were executed aboard a train in Moramanga. None of this appeared to influence Madagascar’s governors. De Coppet’s attitude was clear from the start. When first told of the rebellion, he promised to meet war with war.80

As for de Chevigné, in his mind statehood for Madagascar made no sense: remove the rotten apples, get economic activity and welfare reforms going again, and all would be well.81 Even the Communist Party, more critical of army repression after leaving the coalition in May 1947, soon afterwards issued a formal statement at their annual congress inviting the Malagasy to work alongside the French working class within the fold of the French Union.82 The ban on the MDRM, and the execution or detention of its senior cadres, changed the terms of political engagement in post-rebellion Madagascar. With so many MDRM organizers in detention, the movement relied on local activists, many of them Merina women with familial as well as political ties to the party, to sustain the movement’s grass-roots organization and journalistic output.83 Understandably, their activism focused less on party issues, more on campaigning for the release of Malagasy political prisoners from the harsh confines of places like Nosy Lava, infamous as Madagascar’s bagne (penal colony).84 The fight to re-impose French rule had purchased another decade of colonial control, but at enormous human cost and for scant political or economic benefit.

Madagascar’s colonial politics may have been thrown into stasis but elsewhere the fate of empires moved on. By mid 1954 French withdrawal from Morocco and Tunisia was a realistic expectation. Indochina was lost. And a more peaceful path to decolonization in francophone West Africa was being carved by electoral reforms, inward investment, and gradual loosening of administrative control. The Non-Aligned Movement was making its presence felt on the international stage at the United Nations, in socialist inter-nationalist gatherings, new development projects, and health initiatives. Aid agencies and other NGOs, civil rights groups in the United States, and the gradual shift of anti-colonialist thinking from the margins of European politics towards the mainstream, all these transnational factors also worked slowly but surely to help inject new vigour into Malagasy domestic politics. There were other, more tangible, changes as well. Madagascar fell within the ambit of the Gaston Defferre law, an enabling act eponymously named after the Minister for Overseas France (and discussed at greater length in Chapter 9). The law’s fundamental purpose was to kick-start democratization in francophone black Africa, albeit at a rate still determined by France. Introduction of universal suffrage underpinned other, practical, measures designed to make vibrant local democracy a reality. Piece by piece, colonial administration, once highly centralized and autocratic, was dismantled and supplanted by regional assemblies and communal councils.

The principal beneficiary of this gradual political thaw was likely to be the PADESM, the pro-administration party long favoured as an antidote to the MDRM. With the prospect of exercising real sovereign power tantalizingly close, the PADESM grew more factionalized. The party’s more progressive wing, led by Philibert Tsiranana, a French-educated côtier, broke away to form a new coalition with the Front national malgache, the party that had filled the void left by the MDRM in the Merina heartland. In December 1956 the two groups fused into the Parti social démocrate (PSD), a broad-church grouping with genuine inter-ethnic appeal. The PSD romped home in December 1956 municipal elections, the first held after introduction of Gaston Defferre’s electoral reforms. From the outset Tsiranana made endorsed amicable long-term relations with France, thus assuring the PSD the unswerving support of the outgoing French administration. Few were surprised at the strongly PSD complexion of Madagascar’s first national government established in late 1958.85

Soon afterwards 83 per cent of Malagasy voters approved Madagascar’s inclusion within the new constitutional arrangements of the French Community, the looser imperial organization launched alongside the French Fifth Republic as replacement to the French Union. But certain indicators gave the lie to the image of normality restored. A more telling result was registered in the province of Tananarive, where a narrow majority of 50.5 per cent voted ‘non’. The capital and the surrounding central highlands retained at least some of their nationalist militancy, and were contemptuous of Tsiranana’s honeyed promises of harmonious Franco-Malagasy partnership.86 Clearly, memories of revolt lingered. Over the summer what remained of the colonial garrison and the island’s gendarmerie were surreptitiously reinforced in anticipation of renewed disorder.87 In the event, public disaffection in and around Tananarive never exploded into violence. The Republic of Madagascar was proclaimed on 14 October 1958 in the Place d’Andohalo, the forum in which the Merina dynasty’s royal decrees were announced to Tananarive’s nineteenth-century inhabitants.

Madagascar’s 1947 revolt was the largest rebellion in French-ruled Africa for a generation. Soon eclipsed in French popular memory by the even more cataclysmic Algerian War, this island uprising has been remarkably overlooked by historians of French imperialism and of European decolonization more generally. Yet, as we have seen, there is a strong case to be made that the rebellion set the Fourth Republic on the road to increasingly violent post-war fight strategies that tore apart not only Malagasy society but those of Vietnam and Algeria as well. The French ethnographer Octave Mannoni, a long-serving official in Madagascar’s colonial administration who developed a keen interest in ‘native psychology’, characterized the brutal French suppression of the revolt as a type of ‘theatrical violence’. Mass killings of villagers and novel forms of murder such as dropping victims from aircraft were equally demonstrative. These were acts intended to restore order to the minds of an indigenous population whom Mannoni considered psychologically dependent on the stern hand of external authority.88

Mannoni’s diagnosis seems crass in retrospect. But nor can popular motives for revolt be reduced to ‘national independence’, a term whose bland homogeneity flattens out the multiplicity of grievances felt by Malagasy of different ethnicity, socio-economic status, and occupation. In the rebellion’s eastern heartlands, dissent was impelled by labour requisition, loss of ancestral land, and perennial rural poverty. To these material grievances, long experience of cultural denigration and ethnic discrimination were added. And then there was the pressure of MDRM activism in towns and village settlements across the island, its messengers sometimes genuinely appealing, occasionally locally coercive.89 For some MDRM activists, particularly those in the major towns who were indoctrinated into Communism in the 1930s, independence was the stepping stone to socialist transformation. For others, including the senior leadership, autonomy with the concomitant end to French manipulation of Malagasy civil society and cultural practices was the more viable goal. For still others, the death or incarceration of family members catalysed political engagement.

Extraneous factors and transnational pressures also came into play. The post-war return of thousands of Malagasy ex-servicemen, many of them highly politicized, was one such. An awareness of international public and media interest in manifest colonial abuses was another. The Madagascar revolt and the manner of its suppression were, in this sense, intimately linked with contemporaneous decolonization on the other side of the Indian Ocean and, further on, to Vietnam.90 Finally, the apparent efficaciousness of severe French repression, not so much targeted counter-insurgency as mass punishment, fostered more permissive official attitudes towards the containment of colonial disorder.

Ethical opposition in France and elsewhere to the crackdown was insufficient to counter this, a fact confirmed by the detention of thousands of Malagasy political prisoners. Even the macabre theatricality of the revolt’s violence would soon be repeated. Ten years after the uprising began, when the urban warfare between French security forces and their nationalist opponents in Algiers was at its peak in February 1957, the secretary-general at the city’s police prefecture let slip that some 3,024 people had been ‘disappeared’, the majority of them thrown from helicopters into the sea.91 Madagascar’s revolt and the fight it elicited would prove less the exception than the rule.